Abstract

Due to their simple structure (two bond species randomly arranged on a cubic lattice), the zincblende A1−xBxC semiconductor alloys (zb-SCA) set a benchmark to explore how physical properties are impacted by disorder. A longstanding controversy was whether the lattice dynamics (phonons), governed by the bond force constant, i.e., a local physical property, is blind to the alloy disorder or actually sees it. Over the past two decades, we introduced the percolation model (PM) that distinguishes between like bonds depending on whether they vibrate in same (homo) or alien (hetero) environments (1-bond → 2-mode scheme). The PM seems to apply universally among zb-SCA, and hence would solve the controversy in favor of the second scenario. Here our aim is to take one step forward and complete in the main lines a PM-based taxonomy of high-pressure vibration spectra of zb-SCA. This might clarify how a disordered atomic alloy, seen by each bond species in terms of a homo/hetero composite (i.e., at the unusual mesoscopic scale) from the angle of the PM, behaves when the lattice shrinks under hydrostatic pressure. We focus on Cd1−xZnxTe as the last sensitive pending case. This tidying-up exercise is attractive at the fundamental level and useful for projecting phonon-based devices involving zb-SCA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cubic atomic alloys form ultimately simple systems out of complex media1. They assimilate with ideal composite objects, setting a benchmark for studying how the physical properties are impacted by disorder in a context of percolation2. In particular, the lattice dynamics (phonons), governed by the bond force constant, i.e., a local physical property, is potentially sensitive to the alloy disorder at the ultimate atom scale.

Following Born and Huang3, the transverse (TO) and longitudinal (LO) optical (phonon) modes of the zincblende semiconductor alloys (zb-SCA) have been extensively studied since the emergence of such systems in the 1960s, both experimentally using infrared-IR reflectivity and Raman scattering4 and theoretically using, first, a mean field approximation5 and, then, a supercell approach6,7 avoiding any approximation to treat the alloy disorder1,8,9. The central question was whether the optical modes of a A1−xBxC zb-SCA are “blind” to the alloy disorder and hence generate a single mode per bond at a given composition \(x\) (1-bond → 1-mode—scheme 1), as for the pure AC and BC compounds, or actually “see” the alloy disorder and divide into submodes reflecting natural fluctuations in the local composition inherent to alloying (1-bond → multi-mode—scheme 2), to clarify, then, in terms of number and nature of modes.

State of the art—GaAs1−xPx as a case study

In our view, a paradigmatic zb-SCA in this “scheme 1 vs. scheme 2” controversy is GaAs1−xPx. It was one of the first experimental case studies among zb-SCA4 and its optical mode behavior continues to be debated10. As such, this system offers a suitable vehicle for briefly recapitulating the history of the controversy, and also to outline various phenomenological models used to explain the optical modes of zb-SCA.

A short chronology should emphasize two pioneering IR-reflectivity studies of GaAsxP1−x that revealed separate Ga–As and Ga–P optical bands with a fine structure in each case11,12.

Chen, Shokley and Pearson11 interpreted the GaAsxP1−x IR pattern in the simplest manner, i.e., through merely two oscillators {1 × (Ga–As),1 × (Ga–P}, in line with scheme 1, by voluntarily ignoring the Ga–As and Ga–P fine structures. This crude 1-bond → 1-mode scheme was formalized by the cited authors into the random element isodisplacement (REI) model applying to the non-polar13 TO modes probed in IR-Raman experiments, governed by short-range spring-like restoring forces. This REI model was subsequently extended to the polar13 LO modes by taking into account the long-range Coulombian restoring force between the cations and anions of a zb-SCA. The resulting modified-REI (MREI) model14 (outlined by thin lines in Fig. 1—central panel) remains a reference today1.

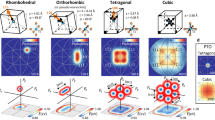

Taxonomy of high pressure Raman spectra of zincblende A1−xBxC semiconductor alloys based on the percolation model. Schematic TO-overview of the percolation model (PM) that distinguishes between bond vibrations (subscript in the used TO notation) in homo and hetero environments (superscript), originally worked out for the highly-contrasted zb-Zn1−xBex-chalcogenides (central panel). The PM-scheme notably features a change in slope in the “TO-frequency vs. \(x\)” variations at the B-C (\({x}_{B-C,perco}\)~0.19) and A-C (\({x}_{A-C,perco}\)~0.81) bond percolation thresholds (emphasized by dotted arrows), in principle. (a) The PM covers the historical MREI and cluster behaviors corresponding to unimodal—(thick lines) and quadrimodal-TO (colored lines) behaviors per bond, respectively, with three MREI variants depending on whether the two modes per alloy are well-separated (2-mode type), close (1-mode type) or cross each other (intermediary type). The MREI model is blind to the local environment, by construction (see text). The cluster model distinguishes between vibrations of, e.g., B–C bonds depending on the C-centered tetrahedron-cluster they belong to, with one to four B atoms at the vertices (abbreviated C:1B to C:4B). Each MREI branch accordingly divides in four cluster sub-branches (top-left panel). (b) Under pressure the distinct PM-doublet due to the short/stiff bond (usually) vibrating at high frequency, e.g., B–C, either diverges or converges depending on the relative hardening rates of the homo and hetero environments, governed by the volume dependence of the bond ionicity (\({f}_{i}\)), as indicated. The convergence follows distinct paths depending on whether B–C is dispersed in chain (\(x\)≤\({x}_{A-C}\)=0.81, marking the A–C bond percolation threshold) or matrix-like (\(x\)≥\({x}_{A-C}\))—leading either to the achievement of a “phonon exceptional point” at the resonance (interrupting the convergence process, ⊡), or to a proper inversion post resonance, ⊠—as sketched out.

Verleur and Barker12 (VB) addressed the Ga-As and Ga-P fine structures beyond the (M)REI model by introducing their cluster model (CM) assuming a sensitivity of bond vibrations to first neighbors. Accordingly, the like bonds of a given species, e.g., Ga-P, vibrate at (slightly) different frequencies depending on the Ga-centered tetrahedron-cluster they belong to, among four possible ones in a zb-SCA, i.e., with one to four P atoms at the vertices (and As otherwise). This comes to divide each MREI mode into four CM submodes (1-bond → 4-mode scheme, as sketched out in Fig. 1a—top inset). VB achieved a fair modeling of their raw GaAs1−xPx IR-reflectivity spectra within their CM, albeit only by assuming a pronounced deviation from the ideal random substitution towards clustering12. Since then, an optical multi-mode behavior per bond in the IR-Raman spectra of a zb-SCA was deemed to be “abnormal”, the sign of a far from random A ↔ B substitution. This has led to discard scheme 2, leaving the MREI-like scheme 1 as the only valid for a random zb-SCA1,4,8.

However, subsequent extended X-ray absorption-fine-structure measurements15 proved GaAs1−xPx to be random. Hence,the fine structuring of the optical modes would be intrinsic to random zb-SCAlloying, in line with scheme 2. In fact, the raw GaAs1−xPx IR-reflectivity spectra of VB12 were lately modeled on the basis of a random As ↔ P substitution within the original version of our percolation model (PM) assuming a sensitivity of bond vibrations to their “same” (homo) or “alien” (hetero) first-neighbor environments (1-bond → 2-mode scheme16—the resulting bimodal signal per bond is referred to as a PM-doublet hereafter). This rehabilitated scheme 2 against scheme 1.

The percolation model—towards a unified understanding of the optical modes of zb-SCA

Within the PM, the homo/hetero first-neighbor environments of a bond are defined at one-dimension (1D) along the linear chain approximation, and not in the three-dimensional (3D) crystal as for the CM16. The 3D → 1D shift is justified by the long wavelength of the exciting light in IR/Raman experiments. This gives access to long wavelength vibrations, in which atom displacements replicate as such from unit cell to unit cell across the crystal. Such uniformity renders a 3D description superfluous; a mere 1D description suffices in principle. Hence, this work is only concerned with long wavelength optical modes (propagating near the center of the Brillouin zone), being referred to as local modes when the bonds involved in such modes are diluted in the crystal.

The main feature of the PM, i.e., the separation between the homo and hetero 1D-environments, occurs because a given bond experiences a different relaxation to accommodate the inherent contrast in bond length/stiffness in a zb-SCA depending on whether it is connected to homo or hetero bonds17. The homo/hetero-connectivity actually affects the bond physical properties. A singularity in the composition dependence of the bond length (l) in zb-SCA has been evidenced ab initio on crossing the bond percolation threshold18, i.e., \({x}_{perco.}\)~19 at.% in a A1−xBxC zb-SCA2. We recall that the latter critical composition corresponds to the first infinite self-connection of the minor bond throughout the crystal, a purely statistical effect of the random A ↔ B substitution2. The singularity in question consists of a small slope discontinuity in the \(l\) vs. \(x\) dependence on crossing \({x}_{perco.}\). The singularity is presumably not accidental, since it was identified for both the stiff/short Ga-N and soft/long Ga-As bonds of the highly-mismatched GaAs1−xNx zb-SCA and as well for both bond species of the better-matched GaAs1−xPx zb-SCA18. Only, the discontinuity shows up more distinctly when the contrast in bond stiffness is larger18.

In echo to the singularity in the composition dependence of the bond length (l), the PM incorporates a singularity in the composition dependence of the Raman frequency (\(\omega\)) at each bond percolation threshold, corresponding to a slope discontinuity near \({x}_{perco.}\) in the \(\omega\) vs. \(x\) dependence (as sketched out in Fig. 1—central panel/thin solid lines). However, so far, such Raman singularity could be resolved experimentally only with the Zn1−xBexVI zb-SCA (with VI standing for Se or Te) that exhibit an unusually large mismatch in bond-length/stiffness19,20,21,22, magnifying bond-related percolation effects2. Still regarding resolution, the 1-bond → 2-mode PM-doublet is especially clear for the short bond that generally vibrates at high frequency. This is because the short bond usually involves the substituent with small covalent radius. As such, the short bond has more room than the long one to accommodate the local strain due to the bond mismatch, with concomitant impact on its Raman frequencies, being more diversified.

The above generic PM has been tested and validated on all archetypal systems of the rather complicated taxonomy of IR-Raman spectra of zb-SCA supported by the historical MREI and cluster (CM) models, outlined in Fig. 1a. This includes three main variants of the 1-bond → 1-mode MREI-type, depending on whether the two modes are well-separated (In1−xGaxAs22), cross each other (In1−xGaxP23) or close (ZnSe1−xTex24), plus the “abnormal” (see above) 1-bond → 4-mode CM-type (As1−xPxGa—Refs.10,16). Hence, the historical MREI/CM-taxonomy has become obsolete. More generally, the PM applied to all tested cubic-SCA with zincblende and diamond structures so far21, suggesting its universality.

Incidentally, besides its interest from a fundamental point of view the PM opens applications, outlined in supplementary information (prefixed S below)—Sec. SI.

Cd1−xZnxTe—a suitable system for testing the pending high-pressure PM-case

In this work our ambition is to elaborate further on the PM scheme 2 by completing in the main lines a PM-based taxonomy/classification of the high-pressure Raman spectra of zb-SCA. It is a matter to elucidate, first, whether the two modes per bond forming its PM-doublet go parallel, diverge or converge under pressure, and, second, what is the driving mechanism in each case. This might help to clarify how the bonding strength varies versus pressure depending on its homo or hetero environment, e.g., on approach to a pressure-induced structural transition. This is important at a fundamental level in view of the crucial role played by high pressure studies in semiconductor physics over the past three quarters of a century25. This issue is unexplored in the literature, apart in our own recent contributions, certainly because the historical consensus originally crystallized around the MREI scheme 1, rendering such studies pointless.

In our preliminary studies two situations (outlined in Fig. 1b) were identified, i.e., the convergence (bottom panel) or the divergence (top panel) of the PM-doublet depending on the relative hardening rates of the homo or hetero environments under pressure, as governed by the volume dependence of the bond ionicity (\(d{f}_{i}/dlnV\))26. If, e.g., the lower submode of the PM-doublet stems from the environment that hardens under pressure faster, it will shift upward under pressure faster than the upper submode, resulting in convergence of the PM-doublet. Otherwise, the PM-doublet diverges. A predictive PM-based bipartition of II–VI and III–V zb-SCA has accordingly been derived recently27.

By looking at it more closely the convergence process poses problem. Existing experiments on zb-SCA classified of the converging type in our PM-bipartition pertained to minor-to-moderate bonds dispersed in chains, as opposed to dominant matrix-like bonds connected in bulk27. At the resonance/crossing, a so-called “phonon exceptional point” was observed, demonstrating the inhibition of coupling. In the latter scenario ①, only the submode due to the hetero environment survives beyond the resonance; while the one from the homo environment freezes27. Extensive detail (beyond what is required in this work), including analytical simulation of the “phonon exceptional point” observed experimentally with zb-Zn~0.5Be~0.5Se, is given in Ref.27. The origin of the “phonon exceptional point” will further be discussed at a later stage in the light of the obtained results in this work. In particular, it is nonsense that scenario ① applies to a matrix-like bond. Taken to extreme this would mean the freezing of a crystal in bulk under pressure as soon as it is corrupted by an impurity. There must be a scenario ② for the matrix-like bond. The elucidation of this alternative convergence is needed to complete, in the main lines, a PM-based taxonomy of the high-pressure Raman spectra of zb-SCA.

Preliminary ab initio tests on BeTe-like supercells containing an isolated Cd21 or Zn28 impurity, sufficient to distinguish between homo (away from impurity) and hetero (close to impurity) environments of a matrix-like bond, revealed an inversion of the PM-doublet under pressure. Hence both PM-submodes of a matrix-like bond would survive beyond the resonance. The “phonon exceptional point” (corresponding to scenario ①, described above) would be avoided in this case. This suggests the genuine crossing of oscillators at the resonance as the convergence scenario ② for a matrix-like bond. There is one experimental (Raman) case report of the pressure-induced inversion of the PM-doublet due to the long (Zn–Te) bond of Zn1−xBexTe (\(x\)~0.1)28. However, the Zn–Te PM-doublet was hardly visible (recall a basic rule that only the short bond exhibits a distinct PM-doublet)10,21. Hence, the gained experimental insight, while positive, is not conclusive.

A decisive test on scenario ② should rely on experiment done on the distinct PM-doublet of the short bond, with a number of requirements on the used A1−xBxC zb-SCA. First, the A ↔ B substitution should be random29, to ascertain that the observed phenomena are intrinsic to a disordered zb-SCA. Second, the crystal should be available in bulk30, as needed to perform high-pressure experiments. Last, the PM-doublet should mark the matrix-like bond31, and moreover be of the converging type under pressure27. Among re-examined zb-SCA within the PM so far (an overview is given, e.g., in Ref.27) the only candidate that fulfills all requirements is zb-Cd1−xZnxTe at large Zn content31.

Recently, we have shown that zb-Cd1−xZnxTe exhibits an outstanding, highly-intricate, Raman signal at ambient pressure31. At \(x\)~0 this fits into a crude two-mode {1 × (Cd–Te),1 × (Zn–Te)} MREI scheme, with the upper/minor LO-impurity mode (\({LO}_{Zn-Te}\)) and the lower/main matrix mode (\({LO}_{Cd-Te}\)) being quasi degenerate. Hence, they couple via their common macroscopic electric field \(E\) reflecting the ionicity of the chemical bonding13 in a zb-crystal. This results in a pair of \({LO}^{-}/{LO}^{+}\)-coupled features in mutual repulsion with similar intensities. At \(x\)~1 the more refined three-mode {1 × (Cd–Te),2 × (Zn–Te)} PM scheme applies. The non-polar TO Raman signal due to the matrix Zn–Te bond splits into two distinct submodes, a lower/main \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Zn}\) and an upper/minor \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) stemming from homo and hetero environments, respectively, as specified via the superscript. This offers an ideal test-bed for scenario ②.

The high-pressure Raman scattering (HP-RS) test of the PM (referred to as the PM-test below) concerned with the mechanical/vibrational properties of the short Zn–Te bond of Cd1−xZnxTe is grounded in a preliminary high-pressure X-ray diffraction (HP-XRD) study offering an insight into the Cd1−xZnxTe bulk mechanical properties. The short-range mechanical (non-polar) coupling that develops in scenario ② at large Zn content between \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Zn}\) and \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) when forced to proximity by pressure is compared with the long-range electrical (polar) coupling involved between \({LO}^{-}\) and \({LO}^{+}\) at small Zn content. The LO-couplings in zb-SCA has been studied in detail in the literature31,32, and we have studied the pressure-induced TO-coupling between the two Be-related PM-submodes of various Zn1−xBex-chalcogenides21,27,28. Yet, zb-Cd1−xZnxTe offers the first opportunity to conduct a consistent comparison of the TO and LO couplings within the same zb-SCA on the same basis of two coupled harmonic oscillators. The discussion is supported by ab initio calculations of the bulk modulus \({B}_{0}\) and of the (TO) lattice dynamics of Cd1−xZnxTe using the AIMPRO (Ab Initio Modeling PROgram) code33,34, and by contour modeling of the TO and LO Cd1−xZnxTe Raman lineshapes within a linear dielectric approach35.

Results and discussion

High-pressure X-ray diffraction (HP-XRD) study of Cd1−xZnxTe

Cd1−xZnxTe HP-XRDiffractograms taken at increasing pressure (upstroke) reveal successive structures: cubic zincblende (zb), hexagonal cinnabar (cb), cubic rock-salt (rs) and orthorhombic Cmcm (cm). Selected data at small (\(x\)= 0.28) and large Zn contents (\(x\)= 0.91) are shown in Fig. S1. The related lattice parameter vs. pressure curves in the native zb-phases are displayed in Fig. 2a and b, respectively. Not surprisingly, the phase sequences replicate the CdTe (zb → cb → rs → cm) and ZnTe (zb → cb → cm) ones, respectively36. Only, Cd0.72Zn0.28Te transforms directly from zb to rs, the transient cb-phase being skipped. Cd ↔ Zn substitution around Te broadens the zincblende stability pressure range of Cd0.90Zn0.1Te (~ 5.5 GPa)37 and Cd0.72Zn0.28Te (~ 6 GPa) compared with CdTe (~ 2.5 GPa)36 and also slightly of Cd0.09Zn0.91Te (~ 10 GPa) compared with ZnTe38 (~ 8.1 GPa). The critical pressure of first departure from the zb-phase is specified in brackets. This situation deviates from Cd ↔ Zn substitution around Se, in which case the same critical pressure varies linearly with composition27. The Cd1−xZnxTe vs. Cd1−xZnxSe discrepancy might relate to the large covalency/stiffness of the Zn–Te bond among II–VI’s, quasi matching that of III–V’s26,39. Hence, even minor CdTe-alloying with the covalent/stiff Zn–Te bond hardens the CdTe-like lattice and delays the departure from the zb-phase in the upstroke. Reversely, minor ZnTe-alloying with the ionic/soft Cd–Te bond would not challenge the natural rigidity of the covalent/stiff ZnTe-like lattice.

High-pressure X-ray diffraction insight into the Cd1−xZnxTe bulk structural/mechanical properties. Pressure dependence of the (a) Cd0.72Zn0.28Te and (b) Cd0.09Zn0.91Te lattice constants (Fig. S1) across successive structural phases (zincblende-zb, cinnabar-cb, rock-salt-rs, Cmcm-cm) in the upstroke. The arrows indicate the destabilization pressure of the zb structure at upstroke. Hollow and plain symbols refer to pure phases and to phase coexistence, respectively—using the same color code as in Fig. S1. (c) Corresponding \({B}_{0}\) values measured in the zb phase across the sample series. The experimental data (empty circles) show also the error bars corresponding to limited acceptable \({B}_{0}^{\prime}\) values on fitting the pressure dependence of the unit cell volume to the Birch-Murnaghan’s equation of state (Fig. S2). The interplay between extreme \({B}_{0}\) and \({B}_{0}^{\prime}\) values is indicated. Existing HP-XRD parent data (cross and full circles) are added for reference purpose. Corresponding ab initio data currently obtained on large (216-atom) zb-supercells optimized to a random substitution (squares) are juxtaposed, for comparison. A straight dotted line/grey area (framed by the parent error bars) is superimposed on experimental/ab initio data as a guide for the eyes.

The bulk modulus \({B}_{0}\) in the zb-phase is obtained from the HP-XRD data by fitting the pressure dependence of the unit cell volume to a Birch-Murnaghan equation of state40 (Fig. S2). The unit cell volume at 0 GPa has been determined by in-house powder XRD using the Cu K \(\alpha\) line. A linear lattice parameter vs. \(x\) variation is revealed (Fig. S2), with \(x\) independently measured by chemical analysis31. The linear trend is replicated in our ab initio data (squares, Fig. S2) and also in alternative zb-Cd1−xZnxTe XRD data, in which \(x\) is determined by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy41.

\({B}_{0}\) and its pressure-derivative at ambient pressure \({B}_{0}^{\prime}\) as functions of \(x\) are shown in Fig. 2c. The only admitted \({B}_{0}^{\prime}\) values are such that the fitted unit cell volume vs. pressure curve passes through all experimental data within error bars (Fig. S2). The as-found \({B}_{0}^{\prime}\) repeatedly fall within the range 3.5–4.2 at any studied composition \(x\), the maximum in \({B}_{0}^{\prime}\) corresponding to the minimum in \({B}_{0}\), and vice versa. \({B}_{0}^{\prime}\) of Cd1−xZnxTe is close to \({B}_{0}^{\prime}\) of ZnTe, fixed to 4 in Ref.42, and not far from \({B}_{0}^{\prime}\) of CdTe, estimated at 6.4 ± 0.6 in Ref.43. Within error bars, in Fig. 2c the fitted \({B}_{0}\) (circles) vary linearly with \(x\) (gray area) between the CdTe (42 ± 2 GPa)43 and ZnTe (52 ± 2 GPa)42 values. The linearity is nicely echoed in our ab initio data (squares). A straight shaded area (framed by the parent error bars) and a straight-dotted line are superimposed on the XRD and ab initio data, as guides for the eyes. The same \({B}_{0}\) vs. \(x\) linear trend was also evidenced with zb-ZnSe1−xTex after a thorough HP-XRD study42. Hence Cd1−xZnxTe looks like a “regular” zb-SCA regarding its bulk mechanical properties.

High-pressure TO Raman scattering (HP-RS) study of Cd1−xZnxTe at large Zn content

From now on the attention turns towards the Cd1−xZnxTe mechanical properties probed at the bond scale by HP-RS. The Raman modes shift upward under pressure44,45,46, due to a pressure-induced increase in bond covalency47. The increase in bond covalency manifests a decrease in bond dynamic charge. This yields a reduction in the Coulombian LO restoring force13. Hence, the TO-LO band shrinks under pressure47, and, along with it, the phonon oscillator strength14 declines (methods).

Zn–Te hardens faster than Cd–Te under pressure, based on the volume derivative of the bond ionicity (\(d{f}_{i}/dlnV\))26. Hence, we anticipate larger Raman drifts for the Zn–Te modes than for the Cd–Te ones (subscript in the used \({TO}_{A-C}^{B}\) PM notation) in Cd1−xZnxTe, and also, for a given bond, a larger Raman drift for the ZnTe-like environment than for the CdTe-like one (superscript). Accordingly, for \(x\)~0.1, the lower CdTe-like \({LO}^{-}\) and upper ZnTe-like \({LO}^{+}\) polar modes should diverge under pressure and decouple electrically. Oppositely, for \(x\)~0.9, the lower \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Zn}\) and upper \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) non-polar submodes should converge under pressure and couple mechanically. The two cases are successively discussed hereafter, starting with the TO’s (\(x\)~0.9), of main interest.

At \(x\)~0.9 (Fig. 3a), the uncoupled minor/upper-\({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) (□) and main/lower-\({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Zn}\) (■) appear to converge in the upstroke until they couple into related \({TO}^{+}\) (○) and \({TO}^{-}\) (●) features, “cross” each other at the resonance (~ 4 GPa, ⊠) and eventually complete an inversion post resonance (○\(\leftrightarrow\)●, ~ 9 GPa) – the minor mode is deconvoluted for clarity (yellow curve). The full process is sequenced in Fig. S3. The inversion is reversible in the downstroke (Fig. S3, dotted curve) and replicates at \(x\)=0.87 (Fig. S3), hence robust. Note that a coupled mode cannot be assigned either a given bond or a specific environment. A mere −/+ superscript is used to indicate the lower/upper frequency.

High pressure Raman insight into the zb-Cd1−xZnxTe bond vibrational/mechanical properties at moderate Cd/Zn-alloying. (a) Experimental TO Raman spectra of Cd0.09Zn0.91Te at selected pressures. Uncoupled dominant \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Zn}\) (■) and minor \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) (□) modes do cross (⊠) in the upstroke and are inverted at high pressure, as the dominant (●) and minor (○, yellow) ZnTe-like \({TO}^{-}\) and \({TO}^{+}\) coupled modes. (b) Modeling (see methods) of the corresponding TO Raman frequencies (yellow curves) and intensities (brightness of curves) using a weak and constant mechanical coupling (\({\omega }^{\prime}=\) 25 cm−1) between modes. The pressure dependence of the bare-uncoupled \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) and \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Zn}\) frequencies behind \({TO}^{-}\) and \({TO}^{+}\), linearly interpolated (straight dotted/solid curves) between corresponding ab initio values at ambient and maximal pressures (large circles, taken from Fig. S4), are added for reference purpose. (c) Selected experimental high-pressure Cd0.89Zn0.11Te LO Raman spectra manifesting an electrical decoupling of the lower CdTe-like \({LO}^{-}\) (●) and upper ZnTe-like \({LO}^{+}\) (○) modes in the upstroke. The experimental (■) and calculated (black curves) bare-uncoupled TO and the calculated bare-uncoupled LO (red curves) modes behind the LO-coupled ones (yellow curves, circles) are shown at 0 GPa. (d) Modeling (see methods) of the coupled-LO Raman frequencies (yellow curves) and intensities (brightness of curves) and of the related bare-uncoupled LO frequencies and bare-uncoupled TO frequencies in the upstroke. Corresponding ab initio TO frequencies at ambient and maximal pressures (large circles, taken from Fig. S4), are added for reference purpose. (e–f) TO (\(x\)~0.9) and LO (\(x\)~0.1) degrees of mode mixing \({cos}^{2}\theta\) (dashed curves) and \({sin}^{2}\theta\) (dashed-dotted curves) resulting from a compromise between the strength of coupling \(V\) (arrows) and the proximity to the resonance \(\Delta\) (solid curves). \(V\) and \(\Delta\) are differentiated by T- and L-subscripts in the LO-electrical and TO-mechanical cases, respectively. Throughout panels (a)–to–(f) the symbols refer to experimental or ab initio (large circles) data, as indicated in the central panels.

Fair modeling of the ZnTe-like bimodal coupled-(\({TO}^{-},{TO}^{+}\)) Raman signal of Cd0.11Zn0.89Te in course of its inversion, covering frequencies (symbols, bright curves) and intensities (brightness of curves), is achieved (Fig. 3b) by using a simplified version of our RCS for two mechanically coupled (\({TO}^{-},{TO}^{+}\)) oscillators due to the same bond (Zn–Te in this case), established as Eq. 7 in Ref.28, i.e.,

In this simplified expression, the mechanical coupling \(\omega ^{\prime}\) between oscillators \(i\)=(1,2) is only preserved at the denominator; it is omitted at the numerator. Yet, \(\omega ^{\prime}\) implicitly occurs via \({L}_{i}\left(\omega \right)={\left[{\omega }_{T,i}^{j}({x}_{i})\right]}^{2}+{\omega ^{\prime}}^{2}+j{\gamma }_{i}\omega -{\omega }^{2}\), where \({\omega }_{T,i}^{j}({x}_{i})\) is the pressure-dependent eigenfrequency of the bare-uncoupled TO oscillator-\(i\) (behind \({TO}^{-}\) and \({TO}^{+}\)) with fraction \({x}_{i}\) (given in Fig. 4 of Ref.31) vibrating in (homo or hetero) environment-\(j\). The individual damping \({\gamma }_{i}\) per oscillator-\(i\) is minimized (1 cm−1) for better resolution of neighboring (\({TO}^{-}\), \({TO}^{+}\)) features near the resonance/crossing. The RCS is weighted by the pressure-dependent oscillator strength \({S}_{ZnTe}\) and by the ZnTe TO frequency squared, being both well documented in the literature (methods). A weak mechanical coupling—taken constant in a crude approximation—is used, with characteristic frequency \({\omega }^{\prime}\)~25 cm−1 (representing ~ 15% of the ZnTe TO frequency). Linear \({\omega }_{T,i}^{j}({x}_{i})\) vs. pressure variations are considered, assuming that the weak mechanical coupling does not challenge the TO frequencies away from the resonance, on either side of it. A crossing of the bare-uncoupled TO-oscillators around 4 GPa, consistent with experiment, is predicted by interpolation (straight solid and dashed curves—Fig. 3b) between ab initio (large circles) values found at 0 and 10 GPa using a ZnTe-like supercell containing a minimal Cd-impurity motif (Fig. S5). The pressure dependence of the as-set input parameters used to implement Eq. 1 are given in Table 1.

Ab initio high pressure zb-Cd1−xZnxTe TO Raman spectra at large Zn content. Ab initio Cd1−xZnxTe high-pressure TO Raman spectra calculated on large (216-atom) disordered zincblende-supercells at various \(x\) values, as specified. Around the Cd–Te bond percolation threshold (\({x}_{Cd-Te,perco}\)=0.81), the emergence of a minor feature (dotted line) on the low-frequency tail of the dominant Zn–Te feature (solid line) at high pressure suggests an inversion of the bimodal \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Zn}-{TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) PM-doublet when the Zn–Te bond is matrix-like (\(x\)≥\({x}_{Cd-Te}\)), in line with scenario ② (right inset). The minor feature disappears when Zn–Te is dispersed in chains (\(x\)≤\({x}_{Cd-Te}\)), suggesting the degeneracy of the two submodes from the resonance onwards, in line with scenario ① (left inset).

The coupling generates a characteristic anticrossing manifesting the repulsion of oscillators (increasing with \({\omega }^{\prime}\), not shown) near the resonance (~ 4 GPa, ⊠), so small in fact (~ 8 cm−1) that only one quasi symmetrical peak is observed experimentally (Fig. 3a). Notably, a strong (○,●) repulsion is punctually observed just before the resonance (i.e., at ~ 3 GPa), suggesting that \({\omega }^{\prime}\) significantly increases (up to ~ 35 cm−1) on the verge of crossing. The coupling further mediates a dramatic transfer of oscillator strength from the lower submode to the upper one—directly impacting the Raman intensities, resulting in the inversion of the PM-doublet post resonance.

The pressure-induced inversion of the PM-doublet due to the matrix-like Zn–Te bond of Cd1−xZnxTe (\(x\)~0.9), mediated by the free mechanical coupling of oscillators, deviates from the achievement of a “phonon exceptional point” manifesting the hindered mechanical coupling, earlier evidenced with similar bonds dispersed in chains—with the Be–Se bond of Zn1−xBexSe as a paradigmatic case (\(x\)≤0.52)48. This solves the raised issue in the introduction: the TO PM-doublet of a given bond follows separate convergence paths depending on whether the bond is dispersed in chains (scenario ①) or matrix-like (scenario ②).

This points towards the bond percolation threshold of the “alien” bond, i.e., \({x}_{Cd-Te, perco.}\)=0.81 in this case, as the pivotal composition separating scenarios ① and ② for the Zn–Te bond of Cd1−xZnxTe. Waiting for experiment, this pivotal role of \({x}_{Cd-Te, perco}\) is currently tested ab initio using large (216-atom) disordered supercells (methods). The TO features are labelled as bare-uncoupled modes in our ab initio Raman data (Fig. 4). Near \({x}_{Cd-Te, perco.}\) (\(x\)=0.83, 0.79), a small but distinct feature, tentatively assigned as the minor-\({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) (dotted curve), emerges below the main-\({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Zn}\) (solid curve) at 5 GPa, suggesting a TO inversion (sketch ②). Below \({x}_{Cd-Te,perco.}\) (\(x\)=0.7, 0.5) this feature is missing, suggesting a “phonon exceptional point” (sketch ①).

However, scenario ① should be moderated in the case of Cd1−xZnxTe. Indeed, the lower/dominant \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Zn}\) does not freeze on crossing the upper/minor \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) at \(x<{x}_{Cd-Te,perco.}\) – while the “freezing” was observed in all earlier tested zb-SCA21,27,28 in a similar context, i.e., Cd1−xBexTe21, Zn1−xBexTe28, Zn1−xBexSe27,48, ZnSe1−xSx49. Otherwise, at 5 GPa the Zn–Te ab initio signal would be reduced to \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\); therefore, contrary to observation (Fig. 4), it would be smaller for \(x\)=0.7 than for \(x\)=0.5, because \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) strengthens with the Cd content for \(x\ge\) 0.331. Hence, both \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Zn}\) and \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) persist beyond the resonance, but, the crossing is interrupted. Otherwise, at 5 GPa \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) would emerge more distinctly at \(x\)=(0.5, 0.7) than at \(x\)=(0.79, 0.83)—for the same reason as given above, contrary to observation (Fig. 4). We are led to conclude that \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) and \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Zn}\) remain degenerate after crossing, without freezing. They form a unique \({TO}_{Zn-Te}\) mode, meaning that the Zn-Te vibrations have become “blind” to the local environment.

At \(x\le {x}_{Cd-Te,perco.}\), we can see one circumstantial reason and one intrinsic reason why Cd1−xZnxTe develops a moderate variant of scenario ①, i.e., without freezing of the lower/dominant \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Zn}\) on crossing the upper/minor \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\). First, Cd–Te and Zn–Te vibrate at nearly identical frequencies (recall the high-intricacy of the Cd1−xZnxTe optical modes31)—the circumstantial reason: the CdTe and ZnTe TO-LO bands are separated by less than ~ 5 cm−1. Second, in the percolation regime (\({x}_{Zn-Te,perco.}=0.19\le x\le {x}_{Cd-Te,perco.}=0.81\)) the homo and hetero host environments for Zn–Te are finely interlaced (as treelike continua2)—the intrinsic reason. Hence, the hetero and homo environments behind the two Zn–Te submodes cannot be distinguished at the resonance/crossing, either by their dynamics (due to the high intricacy of the optical modes) or by their spatial separation (due to the homo/hetero interlacing). In this case (frequency and spatial barriers unset) the two submodes merge into a unique/collective Zn–Te mode from their crossing/resonance onwards. In the earlier tested zb-SCA listed above, the parent TO-LO bands are well-separated, by at least 40 cm−1 (achieved for ZnSe1−xSx49). The set frequency barrier between the homo or hetero environments of a given bond prevents the formation of a collective mode at the crossing/resonance in the percolation regime—despite the spatial barrier is unset (interlacing). In this case, the strict scenario ① applies, with freezing at the crossing27.

At \(x>{x}_{Cd-Te,perco.}\), the homo or hetero environments of Zn–Te in Cd1−xZnxTe are spatially separated, resembling a dispersion in a swisscheese-like matrix2. The established spatial/topological barrier preserves the individual Zn–Te submodes originating from both environments across the convergence process—despite the frequency barrier being unset, until crossing at the resonance and switching post resonance (scenario ②).

Summarizing, the pressure-induced convergence of the ZnTe-like TO PM-doublet of Cd1−xZnxTe changes around the Cd–Te bond percolation threshold (\({x}_{Cd-Te,perco.}\)) : the convergence follows scenario ① at \(x\le {x}_{Cd-Te,perco}\) and scenario ② at \(x>{x}_{Cd-Te,perco.}\), as sketched out in Fig. 4 (insets). Using minimal impurity motifs, we have checked ab initio that scenarios ① (interruption of crossing) and ② (crossing) are preserved as such for Cd1−xZnxTe by departing from \({x}_{Cd-Te,perco.}\) towards Cd-dilution (\(x\)~1, Fig. S4) and towards Zn-dilution (\(x\)~0, Fig. S4), respectively. The ab initio test on the pivotal role of \({x}_{Cd-Te,perco.}\) is thus positive. More intensive ab initio calculations on larger supercells, beyond our current computational possibilities, would help to ascertain and refine the scenario ① \(\leftrightarrow\) scenario ② transition around \({x}_{Cd-Te,perco.}\).

We are now in a position to complete a PM-based taxonomy of high-pressure Raman spectra of zb-A1−xBxC SCA in the main lines. This recognizes three levels, outlined in Fig. 1b, including.

(i) the divergence or convergence of the Raman PM-doublet due to a given bond, say B-C, depending on the relative \(\frac{\partial {f}_{i}}{\partial lnV}\) values of the homo (BC-like) and hetero (AC-like) environments,

(ii) two convergence paths, leading either to the achievement of a “phonon exceptional point” (scenario ①, ⊡) interrupting the crossing of oscillators at the resonance or to the actual crossing of oscillators (scenario ②, ⊠) resulting in an inversion of oscillators post resonance, depending on whether \(x\ge {x}_{A-C,perco.}\) or \(x<{x}_{A-C,perco.}\), respectively.

Cd1−xZnxTe–TO vs. LO comparison

Whether free or inhibited the mechanical coupling is central to the discussion of the convergence of the Zn–Te TO PM-doublet at \(x\)~0.9. Such intra-bond mechanical coupling is estimated below by comparison with the inter-bond electrical coupling between the quasi-degenerate matrix-\({LO}_{Cd-Te}\) and impurity-\({LO}_{Zn-Te}\) at \(x\)~0.1, offering a natural reference. A prerequisite to a reliable TO vs. LO comparison is the contour modeling of the LO Raman spectra depending on pressure, as already done for the TO’s.

At 0 GPa and 300 K a large Cd1−xZnxTe (\(x\)~0.1) crystal exhibits distinct \({LO}^{-}\) ( ₒ) and \({LO}^{+}\) (•) modes with similar intensities31. The situation is not so clear for a tiny crystal inserted in a diamond anvil cell. For instance, (\({LO}^{-},{LO}^{+}\)) are blurred across the series of Cd0.89Zn0.11Te HP-Raman spectra taken at 300 K by Saqib et al.37. This might relate to the formation of Te inclusions at the laser spot, evidenced by a strong peak at ~ 115 cm−1 (Ref.50). By working at 77 K the Te inclusions are avoided in our case, so that the (\({LO}^{-}\), \({LO}^{+}\)) signal clarifies from 2 GPa onwards (Fig. 3c). Above 2 GPa, \({LO}^{-}\) and \({LO}^{+}\) diverge and \({LO}^{-}\) strengthens against \({LO}^{+}\), two signs of electrical decoupling (Fig. S5), as anticipated.

Fair modeling of the Cd0.89Zn0.11Te LO HP-Raman spectra (Fig. 3d), covering frequencies (bright curves) and intensities (brightness of curves), is achieved by using the LO version of our Raman cross section, given by Eq. 1 of Ref.31. For completeness, a theoretical insight (methods) into the bare/uncoupled-TO (black curves) and bare/uncoupled-LO (red curves, not visible experimentally) Raman modes behind the coupled-LO’s (bright curves) of Cd0.89Zn0.11Te at \(0\) GPa is given in Fig. 3c. Additional LO-insight is separately provided at ~ 3 (Fig. 3c) and ~ 4 GPa (Fig. S5).

We can now proceed with the TO vs. LO comparison. The net efficiencies of the inter-bond (Cd–Te, Zn–Te) LO-electrical coupling at \(x\)~0.1 and of the intra-bond (within the Zn–Te PM-doublet) TO-mechanical coupling at \(x\)~0.9 are estimated within the same model of two coupled harmonic oscillators (mass + restoring electrical/mechanical forces), for consistency. We use the same equations of motion and polarization as originally worked out for the Be–Se PM-doublet of Zn0.5Be0.5Se, given by Eq. 4 of Ref.28. At long wavelength where operates the Raman scattering the lattice dynamics is described at 1D (see introductory section). The elementary oscillator is the stretching of a chemical bond \({u}_{i}\) with reduced mass \({\mu }_{i}\) (\({\mu }_{CdTe}=\) 59.7 \(; {\mu }_{ZnTe}=\) 43.2) governed by a scalar equation of motion with generic form \({\mu }_{i}{\ddot{u}}_{i}=-{k}_{i}{u}_{i}-{k}^{\prime}\left({u}_{i}-{u}_{j}\right)+{Z}_{i}E\). This includes a mechanical restoring force, a mechanical coupling with a neighboring oscillator (subscripted \(j\)) and a Coulombian force due to the long range electric field \(E\) reflecting the ionicity of the chemical bond-\(i\) in a zb-crystal (responsible for the effective charge \({Z}_{i}\)). “Generalized forces” considered in Ref.28 as a convenient means to derive the Raman cross section are currently omitted since the focus is on the dynamic matrix \({\widetilde{M}}_{T,L}\) (the subscript marks the TO/LO character).

The TO vs. LO comparison is concerned with both the strength of coupling and the proximity to the resonance, given by the off-diagonal and diagonal terms of \({\widetilde{M}}_{T,L}\), respectively. This approach is in line with that used in recent work on overdamped-TO27 and LO31 modes. Only, in the present case the TO’s are undamped and the LO’s are studied versus pressure, not composition.

Symmetrical \({\widetilde{M}}_{T,L}\) matrices for the optical modes described as plane waves with frequency \(\omega\) are obtained by substituting the normal coordinates \({Q}_{i,T}=\sqrt{{\mu }_{i}}{u}_{i}\) in the TO case (corresponding to \(E=0\) and \({k}^{\prime}\ne 0\)) and \({Q}_{i,L}=\sqrt{{x}_{i}{\mu }_{i}}{u}_{i}\), in the LO case (corresponding to \(E\ne 0\) – see detail below, and \({k}^{\prime}=0\)—the mechanical coupling is neglected in a first approximation, as justified below) for the actual bond-stretching \({u}_{i}\) (\(i\)=1,2) with reduced mass \({\mu }_{i}\) and fraction \({x}_{i}\) in the crystal, leading to

In this matrix elements, \({\omega }_{T,i}^{2}= {k}_{i}{\mu }_{i}^{-1}\) is the square frequency of the uncoupled TO oscillator-\(i\), \({\omega }^{{\prime}2}={k}^{\prime}{\left({\mu }_{1}{\mu }_{2}\right)}^{-\frac{1}{2}}\) is the square frequency characteristic of the mechanical coupling, \({\Omega }_{i}^{2}={x}_{i}{\varepsilon }_{\infty ,i}{\varepsilon }_{\infty }(x){\left({\omega }_{L}^{2}-{\omega }_{T}^{2}\right)}_{i}\). In the latter term, \({\varepsilon }_{\infty }(x)\) scales linearly with \(x\) between the parent \({\varepsilon }_{\infty ,i}\) values of a given A1−xBxC zb-alloy and \({\left({\omega }_{L}^{2}-{\omega }_{T}^{2}\right)}_{i}\) – related to the TO-LO band to the parent \(i\)-compound—identifies with \(N{Z}_{i}{({\varepsilon }_{0}{\varepsilon }_{\infty ,i}{\mu }_{i})}^{-1}\). \(N\) is the number of bonds per unit crystal volume (taken identical for CdTe and ZnTe in a crude approximation), also involved in the relative dielectric function of the considered two-oscillator (\(TO\) or \(LO\)) system, i.e., \({\varepsilon }_{r}\left(\omega ,{x}_{1},{x}_{2}\right)={\varepsilon }_{\infty }\left(x\right)+N\left({x}_{1}{Z}_{1}{u}_{1}+{x}_{2}{Z}_{2}{u}_{2}\right)\), that vanishes to zero for a LO mode13. Basic sum rules are fulfilled by \(\left({x}_{1},{x}_{2}\right)\) depending on the nature of the considered coupling in Cd1−xZnxTe, as to whether this is inter-bond (\({x}_{1}+{x}_{2}=1\)), i.e., the LO case (\(x\)=0.11), or intra-bond (\({x}_{1}+{x}_{2}=x\)), i.e., the ZnTe-like TO case (\(x\)=0.91). In the latter case, the two (Zn-Te) TO frequencies are differentiated by a superscript specifying the homo/hetero local environment in Table 1, replacing the above generic \({\omega }_{T,i}\) and \({x}_{i}\) notations by the more elaborate \({\omega }_{T,i}^{j}\) and \({x}_{i}^{j}\) one in which the superscript-\(j\) indicates the (homo/hetero) local environment of the Zn–Te vibrating unit specified by the subscript-\(i\). The pressure dependence of the various parameters involved in the \({\widetilde{M}}_{T,L}\)-matrix elements is given in Table 1.

\({\widetilde{M}}_{T,L}\) have the same generic form, with off-diagonal and diagonal terms expressed as \({E}_{i}(P)-{\omega }^{2}\) and \(V\left(P\right)\), respectively, emphasizing the dependence on pressure (\(P\)). The eigenfrequencies \({\omega }^{\pm }\left(P\right)\) and eigenvectors \(\left|{Q}_{\pm }\rangle \right.\) of the coupled modes depending on the strength of the coupling \(V\left(P\right)\) and on the proximity \(\Delta \left(P\right)=\left|\frac{{E}_{2}\left(P\right)-{E}_{1}\left(P\right)}{2}\right|\) to the resonance follow immediately (extensive detail is given in Ref.31).

The unit \(\left|{Q}_{\pm }\rangle \right.\) wavevectors are orthogonal, following from, e.g., \(\left|{Q}_{\pm }\rangle \right.=\left(\begin{array}{c}cos \theta \\ sin \theta \end{array}\right)\). Accordingly, \({cos}^{2}\theta\) and \({sin}^{2}\theta\) specify how much, in percent, the raw-uncoupled \(\left|{Q}_{1}\rangle \right.\) and \(\left|{Q}_{2}\rangle \right.\) oscillators are involved in \(\left|{Q}_{+}\rangle \right.\), respectively, and vice versa for \(\left|{Q}_{-}\rangle \right.\). The net coupling efficiency is captured via \(\left|tan2\theta \right|=V/\Delta\), i.e., in terms of a compromise between the strength of mechanical/electrical coupling (given by the off-diagonal term \(V\)) and the proximity to resonance (given by the difference \(\Delta\) between diagonal terms). The pressure dependence of the cited parameters in the TO and LO cases are shown in Fig. 3e and f, respectively. \(\left|tan2\theta \right|\) achieves maximum on crossing the TO resonance, without equivalent in the LO symmetry since \({LO}^{-}\) and \({LO}^{+}\) break away under pressure. Yet, a significant LO-mixing, attested by \({cos}^{2}\theta\) and \({sin}^{2}\theta\) significantly deviating from 0 and 1, respectively, persists across the pressure range studied experimentally. In contrast, the TO modes mix significantly on approaching the resonance but decouple just after the resonance (⊠). This is because \({V}_{T}\) is much smaller than \({V}_{L}\), by roughly one order of magnitude (arrows), justifying a posteriori our approximation to omit the mechanical coupling in the LO case. The picture is not challenged by adopting a more refined approach (outlined in supplementary information—Sec. SIII) to weight the mechanical coupling suffered by a given (\({u}_{i}\)) oscillator by the fraction (\({x}_{j}\)) of the other (\({u}_{j}\)) oscillator (Fig. S6).

Conclusion

At large Zn content the transverse optical Zn–Te Raman signal of Cd1−xZnxTe splits in two, distinguishing between homo or hetero environments, as explained within the percolation model (PM). This offers the possibility to explore experimentally the pressure-induced convergence of the Raman PM-doublet due to a matrix-like bond of a zincblende semiconductor alloy (zb-SCA).

The convergence proceeds via the free mechanical coupling of oscillators on crossing at the resonance ending up with a genuine inversion of the PM-doublet post resonance. This deviates from the achievement of a “phonon exceptional point” manifesting the interruption of crossing at the resonance, earlier observed in experiment with similar bonds dispersed in chains (\(x\le\) 0.52)27. Different convergence scenarios for matrix-like bonds and bonds dispersed in chains—the two regimes being separated by the percolation threshold of the other bond species—endorse in a new light our view that the lattice dynamics of the zb-SCA basically falls into the scope of percolation. A PM-based taxonomy of high-pressure Raman spectra of zb-SCA is accordingly outlined (Fig. 1b), completing that earlier achieved at ambient pressure (Fig. 1a).

Methods

Mixed crystals

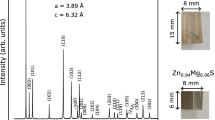

High quality and purity Cd1−xZnxTe single crystals covering the composition domain (\(x\)=0.11, 0.28, 0.53, 0.87, 0.91) are grown by the Bridgman method30. A similar Cd0.89Be0.11Te crystal21 is used for calibration purpose. All studied alloys crystallize in the zincblende structure at 0 GPa, verified by powder X-ray diffraction measurements. Examples of diffractograms taken at ~ 0 GPa at well-spanned \(x\) values independently determined by chemical analysis (using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy in combination with the induced coupling plasma method) are shown in Ref.31. More detail concerning the samples is given in the cited work.

High-pressure Raman scattering

High-pressure Raman scattering (HP-RS) is performed on a single crystal in a Chervin-type diamond anvil cell51 (DAC, ~ 350 µm diamond culet diameter). Different pressure transmitting media are used at 300 and 77K (setting the cell into a Helium flow cryostat system), namely 16:3:1 methanol–ethanol–water mixture, hydrostatic up to ~ 10.5 GPa52, and Ne, hydrostatic up to ~ 15 GPa52, respectively. Ruby spheres luminescence is used as a pressure gauge53.

A selective Fröhlich-enhanced54 LO insight at \(x\)~0.1 is obtained by using the 488.0 nm Ar+ laser line, near-resonant with the direct \({E}_{0}+{\Delta }_{0}\) gap between the lower light hole valence band and the conduction band31. Low temperature (77 K) is used to minimize the formation of Te inclusions, a notorious problem with CdTe-like crystals50, emphasized by laser heating of the tiny sample inside the DAC. In such crystals, \({E}_{0}\) increases with pressure55 and by decreasing temperature56, which improves the resonance, further enhancing the LO’s. The Raman signal of Cd1−xZnxTe remains LO-like over the whole composition domain whether using the 488.0 nm or 514.5 nm Ar+ laser excitations (Ref.31—Fig. S4 therein). The TO modes, of main interest, are only accessible at large Zn content (\(x\)=0.87, 0.91) well beyond the Cd-Te bond percolation threshold (\({x}_{Cd-Te,perco.}=\) 0.81) by using the non-resonant 632.8 nm laser line31. At \(x\)~0.9 Cd1−xZnxTe is transparent to the latter laser excitation31. This suppresses the need for low temperature and also the LO enhancement, hence clarifying the TO insight.

Modeling of the Raman signal depending on pressure

A sensitive input parameter in modeling the Cd1−xZnxTe TO and LO Raman lineshapes is the oscillator strength awarded per mode at a given pressure, scaling as the oscillator fraction in the crystal14. Once the latter is properly determined, as recently done within the PM-version worked out for Cd1−xZnxTe31 at ambient pressure, we are left to elucidate the pressure dependence of the parent (CdTe and ZnTe) oscillator strengths \(S={\varepsilon }_{\infty }\cdot \frac{{\omega }_{L}^{2}-{\omega }_{T}^{2}}{{\omega }_{T}^{2}}\), with (\({\omega }_{T},{\omega }_{L}\)) standing for the (TO, LO) Raman frequencies and \({\varepsilon }_{\infty }\) representing the high-frequency dielectric constant (at \(\omega \gg {\omega }_{T}\))14. In a first approximation, \({\varepsilon }_{\infty }\) is taken constant for ZnTe and CdTe (Table 1)—using the values given in Ref.57, based on existing calculations using the ab initio WIEN2k code58 and a semi-empirical tight-binding method59, respectively. These reveal for ZnTe a stability of \({\varepsilon }_{\infty }\) within 4% between 0 and 20 GPa and for CdTe a variation of \({\varepsilon }_{\infty }\) less than 9% between 0 and 5 GPa, matching the pressure domain probed in the current Cd0.89Zn0.11Te HP-RS study. The pressure dependence of the \({\omega }_{T}-{\omega }_{L}\) optic band is well-documented for ZnTe38. For CdTe, only the pressure dependence of \({\omega }_{L}\) could be accessed experimentally46. An accurate assessment of the parent CdTe oscillator strength (\({S}_{CdTe}\)) depending on pressure, notably involving the TO-LO splitting, is especially crucial at large Cd content. A direct insight is currently gained in situ by measuring the TO-LO splitting of the uncoupled Cd–Te mode of Cd0.89Be0.11Te placed nearby Cd0.89Zn0.11Te inside the DAC (Fig. S5—photo) as an internal calibrant, considering that the Cd-Te oscillator strength scales linearly with the Cd content14. \({\varepsilon }_{\infty }\) being fixed as specified above (Table 1), and using the \({TO}_{Cd-Te}\) frequency of Cd0.89Be0.11Te apparent in experiment (Fig. S5), \({S}_{CdTe}\) at a given pressure is adjusted so that the LO version of the Cd0.89Be0.11Te Raman cross section generates a \({LO}_{Cd-Te}\) mode for Cd0.89Be0.11Te exactly at the observed frequency at that pressure (Fig. S5). Additional input parameters coming into the expression of the Raman cross section (RCS) are the Faust-Henry coefficients of the parent CdTe (− 0.14) and ZnTe (− 0.11) compounds31, taken independent of pressure and temperature in a crude approximation.

The particular modeling of the Cd0.89Zn0.11Te LO HP-Raman spectra (Fig. 3d), covering frequencies (bright curves) and intensities (brightness of curves), is achieved by using the LO version of our RCS, given by Eq. 1 of Ref.31 The pressure-dependent \({S}_{CdTe}\) obtained from the Cd0.89Be0.11Te internal calibrant (see above) is re-injected as such in the Cd0.89Zn0.11Te RCS to generate blindly \({LO}^{-}\) and \({LO}^{+}\) at a given pressure. Additional input parameters are the TO frequencies of the matrix-\({TO}_{Cd-Te}\) (\({\omega }_{matrix}\)) and impurity-\({TO}_{Zn-Te}\) (\({\omega }_{imp}\)) modes. Only \({\omega }_{matrix}\) is visible in experiment (■\(,\) Fig. 3c and d)—polynomial-adjusted (curved black curve—Fig. 3d), not \({\omega }_{imp}\). A linear \({\omega }_{imp}\) vs. pressure variation is assumed (straight black curve—Fig. 3d). The starting \({\omega }_{imp}\) value at 0 GPa and 77 K is taken from Ref.31 (referring to \({TO}_{Zn-Te}^{Cd}\) of Cd0.89Zn0.11Te in Fig. 1 therein). The \({\omega }_{imp}\) vs. \(x\) slope is adjusted until the theoretical \({LO}^{-}\) and \({LO}^{+}\) frequencies (bright curves) best match experimental values (small circles—Fig. 3d). The as-obtained \({\omega }_{matrix}\) and \({\omega }_{imp}\) values at 0 and 5 GPa match within a few cm−1 the ab initio ones (large circles—Fig. 3d) generated from a CdTe-like supercell with a minimal Zn-impurity motif (Fig. S4). The bare-uncoupled LO due to a given oscillator is obtained by reducing the relative dielectric function of Cd1−xZnxTe—governing the LO RCS—to that sole oscillator, as done, e.g., in Ref.31. The input parameters used to calculate the RCS (Eq. 1) together with those involved in the \({\widetilde{M}}_{T,L}\)-matrix elements (Eqs. 2 and 3) are given in their pressure dependence (when relevant) in Table 1.

High-pressure X-ray diffraction

High-pressure X-ray diffraction (HP-XRD) studies are done at the PSICHE beamline of SOLEIL synchrotron on powdered alloys (\(x\)=0.11, 0.28, 0.53, 0.87, 0.91) using a similar Chervin-type DAC as for HP-RS, with Ne as a pressure transmitting medium. Au powder is added for pressure calibration. The HP-XRD diffractograms, obtained with the 0.3738 Å radiation, are treated via the DIOPTAS software60. \({B}_{0}\) is derived by fitting a third-order Birch-Murnaghan’s equation of state40 to the pressure dependence of the unit cell volume in the native zincblende phase.

First-principles calculations

First-principles calculations of the Cd1−xZnxTe bulk modulus \({B}_{0}\) and TO Raman spectra depending on pressure are implemented by applying the AIMPRO code33,34 to large (216-atom) fully relaxed (lattice constant, atom positions) zincblende-supercells optimized to a random Cd \(\leftrightarrow\) Zn substitution. This is achieved by virtual annealing until the distribution of individual Te-centered Cd/Zn-tetrahedra matches the binomial Bernoulli’s law, as detailed in Ref.31. We have checked therein that the as-obtained “quality of randomization” compares with that of special quasirandom supercells61, in first approximation. \({B}_{0}\) follows from ab initio data in the same way as from HP-XRD ones. The TO Raman spectra are calculated using the formula of de Gironcoli62. More detail on the used ab initio setup is given in Ref.31.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Adachi, S. Properties of Semiconductor Alloys—Group-IV, III-V and II-VI Semiconductors (John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2009).

Stauffer, D. & Aharony, A. Introduction to Percolation Theory, Chap. 2 (Taylor and Francis, Bristol, 1994), p. 17.

Born, M. & Huang, H. Dynamical Theory of Crystal Lattices 105 (Oxford University Press, 1954).

Taylor, D. W. In Optical properties of mixed crystals, edited by Elliott R.J. & Ipatova I.P. (Elsevier, 1988), in Chap. 2—Phonon response theory and the infrared and Raman experiments, p. 35–131.

Bonneville, R. Local-field effects and the ir optical properties of ternary semiconductor alloys. Phys. Rev. B 24, 1987–2002 (1981).

Baroni, S., de Gironcoli, S. & Giannozzi, P. Phonon dispersions in GaxAl1-xAs alloys. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 84–87 (1990).

Zunger, A., Wei, S.-H., Ferreira, L. G. & Bernard, J. E. Special quasi-random structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 353–356 (1990).

Elliott, R. J., Krumhansl, J. A. & Leath, P. L. The theory and properties of randomly disordered crystals and related physical systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 46, 465–543 (1974).

Baroni, S., de Gironcoli, S., Dal Corso, A. & Giannozzi, P. Phonons and related properties of extended systems from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 515–562 (2001).

Elmahjoubi, A., Alhaddad, T., Postnikov, A. V. & Pagès, O. Comment on “Infrared dielectric function of GaAs1-xPx semiconductor alloys near the reststrahlen bands” [Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 172102 (2023)]. Appl. Phys. Lett. 125, 086101 (2024).

Chen, Y. S., Schockley, W. & Pearson, G. L. Lattice vibrations in GaAs1-xPx single crystals. Phys. Rev. 151, 648–656 (1966).

Verleur, H. W. & Barker, A. S. Infrared lattice vibrations in GaAs1-xPx alloys. Phys. Rev. 149, 715–729 (1966).

Claus, R., Mertens, L. & Brandmüller, J. Light Scattering by Phonon-Polaritons (Springer-Verlag, 1975).

Chang, I. F. & Mitra, S. S. Long wavelength optical phonons in mixed crystals. Adv. Phys. 20, 359–404 (1971).

Wu, Z. et al. Extended x-ray-absorption fine-structure study of GaAsxP1-x semiconducting random solid solutions. Phys. Rev. B 48, 8694–8700 (1993).

Pagès, O., Souhabi, J., Postnikov, A. V. & Chafi, A. Percolation versus cluster models for multimode vibration spectra of mixed crystals: GaAsP as a case study. Phys. Rev. B 80, 035204 (2009).

Postnikov, A. V., Pagès, O. & Hugel, J. Lattice dynamics of the mixed semiconductor (Be, Zn)Se from first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 71, 115206 (2005).

Bellaiche, L., Wei, S.-H. & Zunger, A. Localization and percolation in semiconductor alloys: GaAsN vs GaAsP. Phys. Rev. B 54, 17568–17576 (1996).

Pagès, O. et al. Vibrational evidence for a percolative behavior in Zn1-xBexSe. Phys. Rev. B 65, 035213 (2001).

Pagès, O. et al. Long-wave phonons in ZnSe-BeSe mixed crystals: Raman scattering and percolation model. Phys. Rev. B 70, 155319 (2004).

Elmahjoubi, A. et al. Vibrational-mechanical properties of the highly-mismatched Cd1-xBexTe semiconductor alloy—Experiment and ab initio calculations. Sci. Rep. 13, 14571 (2023).

Pagès, O. et al. Percolation picture for long wave phonons in zinc-blende mixed crystals: From (Zn, Be) cahlcogenides to (Ga, In)As. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 18, 577–595 (2006).

Pagès, O., Chafi, A., Fristot, D. & Postnikov, A. V. (Ga, In)P: A standard alloy in the classification of phonon mode behavior. Phys. Rev. B 73, 165206 (2006).

Pagès, O., Souhabi, J., Postnikov, A. V. & Chafi, A. Unification of the phonon mode behavior in semiconductor alloys: Theory and ab initio calculations. Phys. Rev. B 77, 125208 (2008).

Yu, P. High pressure semiconductor physics: Looking toward the future on the shoulder of the past. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 248, 1077–1082 (2011).

Christensen, N. E., Satpathy, S. & Pawlowska, Z. Bonding and ionicity in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 36, 1032 (1987).

Shoker, M. B. et al. Phonon-based partition of (ZnSe-like) semiconductor mixed crystals on approach to their pressure-induced structural transition. Sci. Rep. 10, 19803 (2020).

Shoker, M. B. et al. Exceptional phonon point versus free coupling in Zn1-xBexTe under pressure: An experimental and ab initio Raman study. Sci. Rep. 12, 753 (2022).

Zamir, D. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of II-VI semiconductor alloys. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 6, 2612–2613 (1988).

Strzałkowski, K. The composition effect on the thermal and optical properties across the CdZnTe crystals. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 49, 435106 (2016).

Alhaddad, T. et al. Raman study of Cd1-xZnxTe phonons and phonon-polaritons—Experiment and ab initio calculations. J. Appl. Phys. 133, 065701 (2023).

Groenen, J. et al. Optical-phonon behavior in Ga1-xInxAs: The role of microscopic strains and ionic plasmon coupling. Phys. Rev. B 58, 10452 (1998).

Briddon, P. R. & Jones, R. LDA calculations using a basis of Gaussian orbitals. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 217, 131–171 (2000).

Rayson, M. J. & Briddon, P. R. Rapid iterative method for electronic-structure eigenproblems using localized basis functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 178, 128–134 (2008).

Hon, D. T. & Faust, W. L. Dielectric parametrization of Raman lineshapes for GaP with a plasma of charge carriers. Appl. Phys. 1, 241–256 (1973).

Mujica, A., Rubio, A., Muñoz, A. & Needs, R. High-pressure phases of group-IV, III-V and II-VI compounds. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 863–912 (2003).

Saqib, H. et al. Giant conductivity enhancement: Pressure-induced semiconductor-metal phase transition in Cd0.9Zn0.1Te. Phys. Rev. B 99, 094109 (2019).

Camacho, J., Loa, I., Cantarero, A. & Syassen, K. Vibrational properties of ZnTe at high pressures. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 14, 739–757 (2002).

Vérié, C. Beryllium substitution-mediated covalency engineering of II-VI alloys for lattice elastic rigidity reinforcements. J. Cryst. Growth 184(185), 1061–1066 (1998).

Birch, F. Finite elastic strain of cubic crystals. Phys. Rev. 71, 809–824 (1947).

Schenk, M., Hähnert, I., Duong, L. T. H. & Niebsch, H.-H. Validity of the lattice-parameter Vegard-rule in Cd1-xZnxTe solid solutions. Cryst. Res. Technol. 31, 665–672 (1996).

Pellicer-Porres, J. et al. High-pressure phase diagram of ZnSexTe1−x alloys. Phys. Rev. B 71, 035210 (2005).

McMahon, M. I., Nelmes, R. J., Wright, N. G. & Allan, D. R. Phase transitions in CdTe to 5 GPa. Phys. Rev. B 48, 16246–16251 (1993).

Weinstein, B. A. & Piermarini, G. J. Raman scattering and phonon dispersion in Si and GaP at very high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 12, 1172–1186 (1975).

Weinstein, B. A. Phonon dispersion on zinc chalcogenides under extreme pressure and the metallic transformation. Solid State Commun. 24, 595–598 (1977).

Arora, A., Bartholomew, D. U., Peterson, D. L. & Ramdas, A. K. Raman-scattering study of the high-pressure phase transition in Cd1-xMnxTe. Phys. Rev. B 35, 7966–7971 (1987).

Cardona, M. Pressure dependence of dynamical charges and ionicity of semiconductors. Journal de Physique Colloques 45, C8–29–C8–39 (1984).

Pradhan, G. K. et al. Pressure-induced phonon freezing in the Zn1-xBexSe alloy: A study via the percolation model. Phys. Rev. B 81, 115207 (2010).

Hajj Hussein, R. et al. Pressure-induced phonon freezing in the ZnSeS II-VI mixed crystal: phonon-polaritons and ab initio calculations. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 28, 205401 (2016).

Talwar, D. N., Feng, Z. C., Lee, J.-F. & Becla, P. Extended x-ray absorption fine structure and micro-Raman spectra of Bridgman grown Cd1-xZnxTe ternary alloys. Mater. Res. Express 1, 015018 (2014).

Chervin, J. C., Canny, B., Besson, J. M. & Pruzan, P. A. Diamond anvil cell for IR mirospectroscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 66, 2595–2598 (1995).

Klotz, S., Chervin, J. C., Munsch, P. & Le Marchand, G. Hydostratic limits of 11 pressure transmitting media. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 42, 075413 (2009).

Chervin, J. C., Canny, B. & Mancinelli, M. Ruby-spheres as pressure gauge for optically transparent high pressure cells. High. Press. Res. 21, 305–314 (2001).

Trallero-Giner, C., Cantarero, A. & Cardona, M. One-phonon resonant Raman scattering: Fröhlich exciton-phonon interaction. Phys. Rev. B 40, 4030–4036 (1989).

Deligoz, E., Colakoglu, K. & Ciftci, Y. Elastic, electronic, and lattice dynamical properties of CdS, CdSe, and CdTe. Phys. B 373, 124–130 (2006).

Horodyský, P. & Hlídec, P. Free-exciton absorption in bulk CdTe: Temperature dependence. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 243, 494–501 (2006).

Talwar, D. N., Feng, Z. C. & Becla, P. Impurity-induced phonon disordering in Cd1-xZnxTe ternary alloys. Phys. Rev. B 48, 17064–17070 (1993).

Kenata, R. et al. Elastic, electronic and optical properties of ZnZ, ZnSe and ZnTe under pressure. Comput. Mater. Sci. 38, 29–38 (2006).

Merad, A. E., Kanoun, M. B., Aourag, H., Cibert, J. & Merad, G. Electronic and optical properties of CdTe under hydrostatic pressure effect. Superlattices Microstruct. 32, 25–34 (2002).

Prescher, C. & Prakapenka, V. B. DIOPTAS: A program for reduction of two-dimensional X-ray diffraction data and data exploration. High Press. Res. 35, 223–230 (2015).

Zunger, A., Wei, S.-H., Ferreira, L. G. & Bernard, J. E. Special quasirandom structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 353–356 (1990).

De Gironcoli, S. Phonons in Si-Ge systems: An ab initio interatomic-force-constant approach. Phys. Rev. B 46, 2412–2419 (1992).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge assistance from the PSICHÉ beamline staff of synchrotron SOLEIL (Proposal 20210410 – BAG for PSICHÉ beamline led by Y.L.G., sub-project HP-CdZnTe co-led by A.P. & O.P.), from the IJL core facility (Université de Lorraine – http://ijl.univ-lorraine.fr/recherche/centres-de-competences/rayons-x-et-spectroscopie-moessbauer-x-gamma) for the X-ray diffraction measurements at ambient pressure, and from P. Franchetti for the Raman measurements. VJBT in charge with the ab initio AIMPRO calculations acknowledge the FCT through projects LA/P/0037/2020, UIDB/50025/2020 and UIDP/50025/2020. This work was supported by the French PIA project Lorraine Université d’Excellence, part of the France 2030 Program, reference ANR-15-IDEX-04-LUE, within the ViSA – IRP «Vibrations of Semiconductor Alloys – International Research Partnership» wall-less associated international laboratory (2024–2028), co-funded by the Excellence Initiative – Research University program at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

High quality and purity Cd1-xZnxTe and Cd1-xBexTe single crystals with zincblende structure were grown by using the Bridgman technique by A.M. and K.S. High-pressure X-ray diffraction measurements were done using powders at the PSICHÉ beamline of synchrotron SOLEIL by A.P. and O.P., with the assistance of Y.L.G. and J.-P.I. The obtained X-ray data were subsequently analyzed by T.A. High-pressure Raman spectra on single crystals were recorded at 300 K by M.B.S., T.A. and O.P. and at 77 K by A.P., C.B. and K.B. in collaboration with T.A and O.P. Ab initio calculations of Raman spectra were done by V.J.B.T. using the AIMPRO code. Phenomenological modeling of the TO Raman cross section and of the dynamical matrices for a coupled system of two mechanical–electrical oscillators done by O.P. (within the linear dielectric approach) and T.A. was implemented by T.A. (using the MATLAB programming language). T.A. and O.P. made the figures. O.P. wrote the manuscript, with contributions from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alhaddad, T., Shoker, M.B., Pagès, O. et al. Taxonomy of high pressure vibration spectra of zincblende semiconductor alloys based on the percolation model. Sci Rep 15, 1212 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83070-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83070-7

This article is cited by

-

Hexagonal Zn1-xMgxS sheds light on the lattice dynamics of atomic alloys

Scientific Reports (2025)