Abstract

Background The systemic immunity-inflammation index(SII) is a new indicator of composite inflammatory response. Inflammatory response is an important pathological process in stroke. Therefore, this study sought to investigate the association between SII and stroke. Methods We collected data on participants with SII and stroke from the 2015–2020 cycle of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for the cross-sectional investigation. Multivariate linear regression models were used to test the association between SII and stroke. Fitted smoothing curves and threshold effect analysis were applied to describe the nonlinear relationship. Results A total of 13,287 participants were included in our study, including 611 (4.598%) participants with stroke. In a multivariate linear regression analysis, we found a significant positive association between SII and stroke, and the odds ratio (OR) [95% CI] of SII associating with prevalence of stroke was [1.02 (1.01, 1.04)] (P < 0.01). In subgroup analysis and interaction experiments, we found that this positive relationship was not significantly correlated among different population settings such as age, gender, race, education level, smoking status, high blood pressure, diabetes and coronary heart disease (P for trend > 0.05). Moreover, we found an nonlinear relationship between SII and stroke with an inflection point of 740 (1,000 cells /µl) by using a two-segment linear regression model. Conclusions This study implies that increased SII levels are linked to stroke. To confirm our findings, more large-scale prospective investigations are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is a common acute cerebrovascular disease in the clinical practice, which is caused by the sudden rupture of blood vessels in the brain or the obstruction of cerebral blood vessels resulting in blood not flowing into the corresponding areas of the brain, thus causing damage to the corresponding brain tissues. Currently, stroke has become the second leading cause of death worldwide [1]. In the latest global statistics on heart disease and stroke, an average of 1 in 21 deaths died of stroke [2]. Meanwhile, U.S. stroke prevalence also increased by 7.8% from 2011–2013 to 2020–2022[3]. In recent years, the diagnosis and treatment of stroke has made significant progress, but the number of stroke deaths is still on the rise [4]. How to improve the diagnosis and treatment of stroke is an important part of improving the occurrence and development of stroke.

Inflammation is a biological phenomenon that is recognized as a series of reactions, processes, or states in the body that regulate homeostasis[5]. Numerous studies show that cellular and molecular mediators in the inflammatory response are generally involved in a wide range of biological processes, including tissue remodeling, metabolism, thermogenesis, and neurological function[6]. Modern medicine often uses some quantitative tests to reflect the overall or local inflammatory situation in the body, such as white blood cell(WBC), hypersensitive C-reactive protein(hs-CRP), interleukin-6(IL-6) and other indicators. Systemic immune-inflammation index(SII) is a new type of composite inflammatory response index that can be used to predict inflammation, with good stability, and can assess the local or systemic immune response[7]. Recent studies have shown that SII is not only be used as a prognostic factor in cancer, but also has a certain predictive value for cerebrovascular diseases [8,9,10].

There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that inflammatory markers are closely associated with stroke[11]. Lei Zheng et al[12] showed a positive correlation between the level of cadmium metal in urine and plasma CRP levels at dose concentrations, and concluded that CRP played a 10.1% role in the association between cadmium and stroke through mediated analysis. This suggests that CRP, an inflammatory response marker, plays an associative role in cadmium and stroke, which may lead to stroke through this pathway. Valerian L Altersberger et al[13] also found that WBC was an important independent predictor of intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) in stroke patients, and higher WBC and CRP were positively associated with higher NIHSS, which could assess patient prognosis. These studies show that inflammatory markers can effectively reflect brain tissue damage to a certain extent. However, the association between SII, a novel composite index of inflammatory response, and stroke has not been well studied.

As a result, we investigate the association between SII and stroke through a cross-sectional analysis on data from investigating participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Method

Study population

The NHANES is a representative survey of the US national population conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that uses a sophisticated, multistage, and probabilistic sampling methodology to provide a wealth of information about the general US population’s nutrition and health[14]. All study procedures were authorized by the National Center for Health Statistics’ ethical review board prior to data collection, and all participants gave their signed, informed consent. The entirety of NHANES data is accessible to the general public and can be freely obtained from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm (accessed on 8 May 2024).

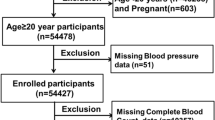

In this study, cross-sectional data of 25,531 participants from three consecutive cycles of the NHANES (2015–2020) were initially included. Participants with complete stroke and SII data were included in the study analysis. The exclusion criteria were set as follows: (1) participants without SII data (n = 5264); (2) participants with no stroke status data (n = 6980). After manual data filtering, we ultimately selected a total of 13,287 participants for subsequent analyses. A detailed flow chart of study participant recruitment was presented in Fig. 1.

SII

The systemic immune-inflammatory index is a novel composite inflammatory response index, which is the exposure variable in our study. In our study, we employed Lymphocyte, neutrophil, and platelet counts when calculating the SII. All indicators were measured by complete blood count using automated hematology analyzing devices (Coulter®DxH 800 analyzer) and presented as ×103 cells/ml. The SII was calculated by the following formula[8,15,16]:

Stroke

Stroke was assessed by whether or not you have been informed of the occurrence of a stroke in the medical conditions questionnaire. “Have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you had a stroke?” If participants answered “yes” to the question, they were judged to have had a stroke[17,18]. By making this determination, we considered stroke as an outcome indicator.

Covariates

Being based on previous publications and biological considerations, we collected as many covariates with known confounding effects on stroke as possible[14]. Covariates were obtained by standardized questionnaires and face-to-face interviews, including age, gender, Body Mass Index (BMI), race, education level, ratio of family income-to-poverty ratio(PIR), smoking status, drinking status, high blood pressure, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. Among them, Race/ethnicity were divided into five categories: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, other Hispanic, Mexican American, and other races. Education levels were divided into three categories: below high school, high school, and above high school. Body mass index (BMI), calculated as weight in kilograms (kg) divided by the square of height in meters (m2), is widely used for estimating overweight/obesity status. Participants who smoked over 100 cigarettes throughout their lifetime were defined as smokers[19]. High blood pressure, diabetes, and coronary heart disease are assessed by the responses in the medical conditions questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

The statistical study was carried out using the statistical computing and graphics software R (version 4.1.3) and EmpowerStats (version:2.0). Baseline tables for the study population were statistically described by stroke and the SII quartiles. The association between SII and stroke was analyzed by multivariate linear regression and the outcome was represented by OR [95%CI]. Model 1 did not adjust for any covariates; Model 2 adjusted for age, gender, and race; Model 3 adjusted for all covariates. By adjusting the variables, smoothed curve fits were done simultaneously. A threshold effects analysis model was used to examine the relationship and inflection point between SII and stroke. Finally, the same statistical study methods described above were conducted for the gender subgroups. It was determined that P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the participants

The study involved 13,287 participants with an average age of 50.15 ± 17.55 years. Among these participants, 48.21% were men, 51.79% were women, 34.19% were non-Hispanic white, 23.83% were non-Hispanic black, 14.15% were Mexican American, 11.64% were other Hispanic, and 16.19% were from other race. Of them, 611 participants (4.598%) had a history of stroke. The mean SII ± SD concentrations were 518.14 ± 343.98 (1,000 cells/µl).

Table 1 lists all clinical characteristics of the participants with stroke as a column-stratified variable. Compared to non-stroke individuals, stroke patents tended to be older (65.12 years vs. 49.81 years), smokers (58.92% vs. 41.05%), less educated (26.51% vs. 20.35%), and more likely to have high blood pressure (74.30% vs. 36.13%), diabetes(36.99% vs. 17.17%), Coronary heart disease (18.82% vs. 3.59%), and the higher SII levels (590.81 vs. 514.64). Moreover, PIR (1.98 vs. 2.18) and alcohol status (2.10 vs. 2.39) were all lower in the stroke group.

Table 2 lists all clinical characteristics of the participants with the quartiles of SII. Among all participants, the prevalence of stroke increased with the higher SII level. The mean SII ± SD concentrations were 518.14 ± 343.98 (1,000 cells/µl), with the values for the different quartiles as follows: quartile 1: < 315.58; quartile 2: 315.58–448.00; quartile 3: 448.00–628.43; and quartile 4: ≥ 628.43 (1,000 cells/µl). Compared to those with the lowest quartile of SII, individuals with the highest quartile of SII were more likely to be older, women, non-Hispanic white, BMI, and smoking status, and they were more likely to have high blood pressure, and diabetes(P < 0.05).

Association of SII with stroke

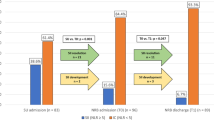

Because the effect value is not apparent, SII/100 is used to amplify the effect value by 100 times. Table 3 shows the multivariate regression analysis between SII/100 and stroke. In the crude [1.04(1.03, 1.06)] and partially adjusted [1.03(1.02,1.05)] models, the SII and stroke show a significant positive association. Upon complete adjustment, the aforementioned positive association remained statistically significant [1.02(1.01, 1.04)]. This positive association remained stable after transforming the SII into quartiles (all P for trend < 0.05). Participants in the highest SII quartile had a 71% increased prevalence of stroke compared to those in the lowest quartile [1.71(1.34, 2.18)].

Subgroup analyses

Table 4 shows subgroup analyses and interaction tests stratified by age, gender, race, education level, smoking status, high blood pressure, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. Our outcomes showed that the relationship between the SII and stroke was not dependent on the above factors (all P for interaction > 0.05).

In subgroup analyses stratified by gender, our results suggest that the positive association between SII and stroke is significant in women [1.04(1.01, 1.06)], but not statistically significant in fully adjusted model for men, as shown in Table 5. Further, we performed a smooth curve fit to describe the nonlinear relationship between the SII and stroke (Figs. 2 and 3). After adjusting for variables: age, gender, race, education level, smoking status, alcohol status, BMI, PIR, high blood pressure, diabetes, and coronary heart disease, our findings suggest that there exists a nonlinear relationship between SII and stroke with an inflection point of 740.00(1000 cells/µl) by using a two-stage linear regression model. After stratifying the analysis by gender, an approximate inverted U-shaped curve was also present in men and women, with inflection points of 772.20 (1,000 cells/µl) and 3551.18 (1,000 cells/µl), respectively (Table 6).

Discussion

Among the 13,287 NHANES participants included in our study, we observed that individuals with stroke had a clearly higher mean SII level than those without stroke. Based on this phenomenon, we confirmed that higher SII was associated with a higher risk of stroke. Then, the results of the subgroup analyses and interaction testing indicated that this connection was similar across population. A nonlinear relationship between SII and stroke was also discovered, with an inflection point of 740.00(1000 cells/µl). After stratifying the analysis by gender, an approximate inverted U-shaped curve was also present in men and women, with inflection points of 772.20 (1,000 cells/µl) and 3551.18 (1,000 cells/µl), respectively. This indicated that SII was an independent crisis factor for stroke when the SII was less than 740.0(1000 cells/µl).

Nowadays, a growing number of studies have found that SII plays an important measure of chronic inflammation, and is significantly associated with cardiovascular-related diseases [20,21]. For example, Dong W et al[22] revealed that SII is an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease. Cao Y et al[23] found that a positive association between SII and all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease in a cross-sectional study of 8524 participants. Liao M et al[24] also reported that carotid atherosclerosis was a risk factor for ischemic stroke, which was significantly positively correlated with SII. Jin N et al[25] showed that a nonlinear relationship between SII and hypertension, with each standard deviation increase in SII increasing the prevalence of hypertension by 9%. In addition, Cheng W et al[26] found an association between higher levels of SII and increased stroke prevalence in patients with asthma, suggesting SII as a potential predictor of stroke in patients with asthma. In our study, we found a positive correlation between SII and stroke, which is consistent with the poor prognosis of SII and cardiovascular-related disease described in earlier studies.

In recent years, several studies have confirmed that inflammation is an important risk factor for stroke and is involved in its main pathological process [27]. A large number of previous studies have demonstrated the effect of NLR and PLR on the assessment of inflammation in stroke. SII is different from those indexes that includes platelet count, neutrophil count and lymphocyte count. SII can comprehensively reflect the three pathways of thrombosis, inflammatory response and adaptive immune response, and provide a more comprehensive assessment of inflammatory response[28–32]. In SII, neutrophil count and lymphocyte count represent the state of inflammation in the blood and platelet count reflects the condition of thrombosis. For example, Cai W et al[33] found that neutrophil constitution in peripheral blood increased soon after stroke onset of patients, and higher neutrophil count indicated detrimental stroke outcomes. Misirlioglu NF et al[34] elevated NLR and SII has been linked to worse outcomes in the context of stroke, including increased risk of stroke severity, larger infarct size, and higher mortality rates. Also, Du J et al[35] demonstrated that platelet count increases the risk for ischemic stroke.

Much evidence has shown that a single inflammatory marker is associated with stroke and reflect the immediate inflammatory state of the body. But, they alone are highly susceptible to the influence of their environment and lifestyle. SII is not the same as a single inflammatory marker. It weakens the instability of the change of a single index through the ratio, which reflects the immune inflammation of the patient’s body as a whole. What’s more, SII can assess the risk factors for stroke-related conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, and atrial fibrillation[36–39]. SII is more accurate than traditional risk factors in assessing coronary artery conditions that can predicts cardiovascular events after coronary intervention[40]. Consistent with our findings, SII is associated with stroke prognosis. Therefore, SII can be used as a comprehensive, accurate and simple indicator to reflect inflammation in cardiovascular diseases, which deserves the attention of healthcare professionals. Inflammation is one of the main pathological mechanisms of stroke. When stroke occurs, local brain tissue is damaged, the blood-brain barrier is destroyed, neutrophils accumulate, inflammatory mediators are released, and lymphocytes undergo apoptosis, which in turn causes secondary damage to stroke and promotes neurological deterioration[41–43]. At the same time, the release of inflammatory factors from the injury site can also lead to abnormal platelet function, which can be directly activated and aggregated, resulting in the blood clots’ formation and stroke recurrence[44]. After stroke, its multiple complications are also related to inflammation [45, 46]. For example, post-stroke immunosuppression is a key factor in the development of stroke-related pneumonia [47]. Following the onset of stroke, a series of inflammatory responses are produced, resulting in immune deficiencies such as decreased peripheral lymphoid count, decreased monocyte activity, and decreased phagocytic activity [48]. Inflammatory response is also one of the main research hotspots in the pathological mechanism of post-stroke depression(PSD)[49]. When the pro-inflammatory factors increase during stroke, the inflammatory response is aggravated, which can affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, reduce the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and enhance the neurocytotoxicity[50–52]. Finally, it promotes the occurrence of PSD[53]. Stroke can also trigger a cascade of reactions, further aggravating the inflammatory response. That causes damage to brain tissue structure and neurological function. Stoll G et al[54] found that platelets would guide lymphocytes to the site of vascular injury during cerebral ischemia, prompting activated platelets to form thrombus. Then, Cognitive function of brain tissue is impaired. As important indicators of inflammation, SII and NLR can indirectly assess the severity of neurological impairment in patients, which is valuable in the prediction of cognitive function after stroke[55].

Our study has some limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional analysis; thus, temporality cannot be ascertained. Furthermore, despite adjusting several relevant confounders, we were unable to rule out the impact of additional confounding factors; therefore, our findings should be interpreted with caution. Third, due to the limitations of the NHANES database, the covariates of this study did not include participants’ medications use; therefore, our findings may not fully reflect the true situation. Despite these limitations, our study has several advantages. Because we used a nationally representative sample, our study is representative of a multiethnic and gender-diverse population in the United States. In addition to this, the large sample size included in our study allowed us to perform a subgroup analysis.

Conclusion

Our findings imply that increased SII levels are linked to stroke. To confirm our findings, more large-scale prospective investigations are needed.

Data availability

The survey data are publicly available on the internet for data users and researchers throughout the world ( www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ ).

Abbreviations

- SII:

-

Systemic immune-inflammation index

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NCHS:

-

National center for health statistics

References

1. Collaborators GS: Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20(10):795–820.

2. Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, Baker-Smith CM, Barone Gibbs B, Beaton AZ, Boehme AK et al: 2024 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024, 149(8):e347-e913.

3. Imoisili OE, Chung A, Tong X, Hayes DK, Loustalot F. Prevalence of Stroke - Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2011–2022. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2024,73(20):449–455.

4. Feigin VL, Owolabi MO: Pragmatic solutions to reduce the global burden of stroke: a World Stroke Organization-Lancet Neurology Commission. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22(12):1160–1206.

5. Medzhitov R: The spectrum of inflammatory responses. Science. 2021, 374(6571):1070–1075.

6. Rankin LC, Artis D: Beyond Host Defense: Emerging Functions of the Immune System in Regulating Complex Tissue Physiology. Cell. 2018, 173(3):554–567.

7. Wang RH, Wen WX, Jiang ZP, Du ZP, Ma ZH, Lu AL, Li HP, Yuan F, Wu SB, Guo JW et al: The clinical value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the occurrence and severity of pneumonia in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Immunol. 2023, 14:1115031.

8. Nøst TH, Alcala K, Urbarova I, Byrne KS, Guida F, Sandanger TM, Johansson M: Systemic inflammation markers and cancer incidence in the UK Biobank. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021, 36(8):841–848.

9. Ding P, Guo H, Sun C, Yang P, Kim NH, Tian Y, Liu Y, Liu P, Li Y, Zhao Q: Combined systemic immune-inflammatory index (SII) and prognostic nutritional index (PNI) predicts chemotherapy response and prognosis in locally advanced gastric cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy with PD-1 antibody sintilimab and XELOX: a prospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22(1):121.

10. Manjunath N, Borkar SA, Agrawal D: Letter: Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Predicts Delayed Cerebral Vasospasm After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2022, 91(1):e27.

11. Couch C, Mallah K, Borucki DM, Bonilha HS, Tomlinson S: State of the science in inflammation and stroke recovery: A systematic review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2022, 65(2):101546.

12. Zheng L, Jing X, Zhang X, Zhong C, Qiu D, Yan Q, Gao Z: Mediation analysis of urinary metals and stroke risk by inflammatory markers. Chemosphere. 2023, 341:140084.

13. Altersberger VL, Enz LS, Sibolt G, Hametner C, Nannoni S, Heldner MR, Stolp J, Jovanovic DR, Zini A, Pezzini A et al: Thrombolysis in stroke patients with elevated inflammatory markers. J Neurol. 2022, 269(10):5405–5419.

14. Mahemuti N, Jing X, Zhang N, Liu C, Li C, Cui Z, Liu Y, Chen J: Association between Systemic Immunity-Inflammation Index and Hyperlipidemia: A Population-Based Study from the NHANES (2015–2020). Nutrients. 2023, 15(5):1177.

15. Xie R, Xiao M, Li L, Ma N, Liu M, Huang X, Liu Q, Zhang Y: Association between SII and hepatic steatosis and liver fibrosis: A population-based study. Front Immunol. 2022, 13:925690.

16. Liu B, Wang J, Li YY, Li KP, Zhang Q: The association between systemic immune-inflammation index and rheumatoid arthritis: evidence from NHANES 1999–2018. Arthritis Res Ther. 2023, 25(1):34.

17. Wang Y, Yang L, Zhang Y, Liu J: Relationship between circadian syndrome and stroke: A cross-sectional study of the national health and nutrition examination survey. Front Neurol 2022, 13:946172.

18. Ye J, Hu Y, Chen X, Yin Z, Yuan X, Huang L, Li K: Association between the weight-adjusted waist index and stroke: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23(1):1689.

19. Liu C, Zhao M, Zhao Y, Hu Y: Association between serum total testosterone levels and metabolic syndrome among adult women in the United States, NHANES 2011–2016. Front Endocrinol. 2023,14:1053665.

20. Karadeniz F, Karadeniz Y, Altuntaş E: Systemic immune-inflammation index, and neutrophilto-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios can predict clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc J Afr 2023, 34:1–7.

21. Song Y, Zhao Y, Shu Y, Zhang L, Cheng W, Wang L, Shu M, Xue B, Wang R, Feng Z et al: Combination model of neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein ratio and system inflammation response index is more valuable for predicting peripheral arterial disease in type 2 diabetic patients: A cross-sectional study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14:1100453.

22. Dong W, Gong Y, Zhao J, Wang Y, Li B, Yang Y: A combined analysis of TyG index, SII index, and SIRI index: positive association with CHD risk and coronary atherosclerosis severity in patients with NAFLD. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14:1281839.

23. Cao Y, Li P, Zhang Y, Qiu M, Li J, Ma S, Yan Y, Li Y, Han Y: Association of systemic immune inflammatory index with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in hypertensive individuals: Results from NHANES. Front Immunol 2023, 14:1087345.

24. Liao M, Liu L, Bai L, Wang R, Liu Y, Zhang L, Han J, Li Y, Qi B: Correlation between novel inflammatory markers and carotid atherosclerosis: A retrospective case-control study. PLoS One 2024, 19(5):e0303869.

25. Jin N, Huang L, Hong J, Zhao X, Hu J, Wang S, Chen X, Rong J, Lu Y: The association between systemic inflammation markers and the prevalence of hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2023, 23(1):615.

26. Cheng W, Bu X, Xu C, Wen G, Kong F, Pan H, Yang S, Chen S: Higher systemic immune-inflammation index and systemic inflammation response index levels are associated with stroke prevalence in the asthmatic population: a cross-sectional analysis of the NHANES 1999–2018. Front Immunol 2023, 14:1191130.

27. Jayaraj RL, Azimullah S, Beiram R, Jalal FY, Rosenberg GA: Neuroinflammation: friend and foe for ischemic stroke. J Neuroinflammation 2019, 16(1):142.

28. Luo J, Thomassen JQ, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Frikke-Schmidt R: Neutrophil counts and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2023, 44(47):4953–4964.

29. Kurtul A, Ornek E: Platelet to Lymphocyte Ratio in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review. Angiology 2019, 70(9):802–818.

30. Chen W, Chen K, Xu Z, Hu Y, Liu Y, Liu W, Hu X, Ye T, Hong J, Zhu H et al: Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Predict Mortality in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers Undergoing Amputations. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2021, 14:821–829.

31. Cifci M, Halhalli HC: The Relationship Between Neutrophil-Lymphocyte and Platelet-Lymphocyte Ratios With Hospital Stays and Mortality in the Emergency Department. Cureus 2020, 12(12):e12179.

32. Fan L, Gui L, Chai EQ, Wei CJ: Routine hematological parameters are associated with short- and long-term prognosis of patients with ischemic stroke. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018, 32(2):e22244.

33. Cai W, Liu S, Hu M, Huang F, Zhu Q, Qiu W, Hu X, Colello J, Zheng SG, Lu Z: Functional Dynamics of Neutrophils After Ischemic Stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2020, 11(1):108–121.

34. Misirlioglu NF, Uzun N, Ozen GD, Çalik M, Altinbilek E, Sutasir N, Baykara Sayili S, Uzun H: The Relationship between Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratios with Nutritional Status, Risk of Nutritional Indices, Prognostic Nutritional Indices and Morbidity in Patients with Ischemic Stroke. Nutrients. 2024, 16(8):1225.

35. Du J, Wang Q, He B, Liu P, Chen JY, Quan H, Ma X: Association of mean platelet volume and platelet count with the development and prognosis of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Int J Lab Hematol 2016, 38(3):233–239.

36. Chen Y, Li Y, Liu M, Xu W, Tong S, Liu K: Association between systemic immunity-inflammation index and hypertension in US adults from NHANES 1999–2018. Sci Rep 2024, 14(1):5677.

37. Nie Y, Zhou H, Wang J, Kan H: Association between systemic immune-inflammation index and diabetes: a population-based study from the NHANES. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14:1245199.

38. Dziedzic EA, Gąsior JS, Tuzimek A, Paleczny J, Junka A, Dąbrowski M, Jankowski P: Investigation of the Associations of Novel Inflammatory Biomarkers-Systemic Inflammatory Index (SII) and Systemic Inflammatory Response Index (SIRI)-With the Severity of Coronary Artery Disease and Acute Coronary Syndrome Occurrence. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23(17).

39. Li Q, Nie J, Cao M, Luo C, Sun C: Association between inflammation markers and all-cause mortality in critical ill patients with atrial fibrillation: Analysis of the Multi-Parameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care (MIMIC-IV) database. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2024, 51:101372.

40. Yang YL, Wu CH, Hsu PF, Chen SC, Huang SS, Chan WL, Lin SJ, Chou CY, Chen JW, Pan JP et al: Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) predicted clinical outcome in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur J Clin Invest 2020, 50(5):e13230.

41. Li W, Cao F, Takase H, Arai K, Lo EH, Lok J: Blood-Brain Barrier Mechanisms in Stroke and Trauma. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2022, 273:267–293.

42. Kelly PJ, Lemmens R, Tsivgoulis G: Inflammation and Stroke Risk: A New Target for Prevention. Stroke. 2021, 52(8):2697–2706.

43. Candelario-Jalil E, Dijkhuizen RM, Magnus T: Neuroinflammation, Stroke, Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction, and Imaging Modalities. Stroke. 2022, 53(5):1473–1486.

44. Denorme F, Rustad JL, Campbell RA: Brothers in arms: platelets and neutrophils in ischemic stroke. Curr Opin Hematol 2021, 28(5):301–307.

45. Simats A, Liesz A: Systemic inflammation after stroke: implications for post-stroke comorbidities. EMBO Mol Med 2022, 14(9):e16269.

46. Villa RF, Ferrari F, Moretti A: Post-stroke depression: Mechanisms and pharmacological treatment. Pharmacol Ther 2018, 184:131–144.

47. Liu DD, Chu SF, Chen C, Yang PF, Chen NH, He X: Research progress in stroke-induced immunodepression syndrome (SIDS) and stroke-associated pneumonia (SAP). Neurochem Int 2018, 114:42–54.

48. Wang Y, Zhang JH, Sheng J, Shao A: Immunoreactive Cells After Cerebral Ischemia. Front Immunol 2019, 10:2781.

49. Medeiros GC, Roy D, Kontos N, Beach SR: Post-stroke depression: A 2020 updated review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2020, 66:70–80.

50. Bai Y, Sui R, Zhang L, Bai B, Zhu Y, Jiang H: Resveratrol Improves Cognitive Function in Post-stroke Depression Rats by Repressing Inflammatory Reactions and Oxidative Stress via the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway. Neuroscience. 2024, 541:50–63.

51. Kang HJ, Bae KY, Kim SW, Kim JT, Park MS, Cho KH, Kim JM: Effects of interleukin-6, interleukin-18, and statin use, evaluated at acute stroke, on post-stroke depression during 1-year follow-up. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 72:156–160.

52. Kim JM, Kang HJ, Kim JW, Bae KY, Kim SW, Kim JT, Park MS, Cho KH: Associations of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and Interleukin-1β Levels and Polymorphisms with Post-Stroke Depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017, 25(12):1300–1308.

53. Liegey JS, Sagnier S, Debruxelles S, Poli M, Olindo S, Renou P, Rouanet F, Moal B, Tourdias T, Sibon I: Influence of inflammatory status in the acute phase of stroke on post-stroke depression. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2021, 177(8):941–946.

54. Stoll G, Nieswandt B: Thrombo-inflammation in acute ischaemic stroke - implications for treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 2019, 15(8):473–481.

55. Senadim S, Çoban E, Tekin B, Balcik ZE, Köksal A, Soysal A, Ataklı D: The inflammatory markers and prognosis of cervicocephalic artery dissection: a stroke center study from a tertiary hospital. Neurol Sci 2020, 41(12):3741–3745.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants in this study.

Funding

The study was supported by the Hebei Provincial Science and Technology Programme Funding (Key R&D Programme) Projects (No.20377710D); Hebei Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Scientific Research Programme Key Projects (No.Z2022008); Key Project of Scientific Research Capacity Improvement of Hebei University of Chinese Medicine (No.KTZ2019028); Hebei Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Scientific Research Program (No.2025040).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RS, YT, and JT designed the research. RS, YT, QL, JZ, ZZ, YS and ZX collected, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. RS, YT and JT revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Ethical statement

The portions of this study involving human participants, human materials, or human data were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the NCHS Ethics Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, R., Tian, Y., Tian, J. et al. Association between the systemic immunity-inflammation index and stroke: a population-based study from NHANES (2015–2020). Sci Rep 15, 381 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83073-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83073-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The Naples prognostic score as a nutritional and inflammatory biomarkers of stroke prevalence and all-cause mortality: insights from NHANES

Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition (2025)

-

Associations between naples prognostic score and stroke and mortality among older adults

European Journal of Medical Research (2025)