Abstract

Atherosclerotic vascular changes can begin during childhood, providing risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in adulthood. Identifiable risk factors such as dyslipidemia accelerate this process for some children. The apolipoprotein B (APOB) gene could help explain the inter-individual variability in lipid levels among young individuals and identify groups that require greater attention to prevent CVD. A cross-sectional study was conducted with school-aged children and adolescents in Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais. The study evaluated cardiovascular risk factors’ variables and XbaI polymorphism in the APOB gene for associations with increased total cholesterol (TC). The prevalence of increased TC was notably high, reaching 68.9% in the study population. Carriers of the variant T allele were 1.45 times more likely to develop increased TC in a dominant model (1.09–1.94, p = 0.011). After adjustments, excess weight and a family history of dyslipidemia interacted significantly with XbaI polymorphism in increased TC, resulting in Odds Ratio of 1.74 (1.11–2.71, p = 0.015) and 2.04 (1.14–3.67, p = 0.016), respectively. The results suggest that XbaI polymorphism in the APOB gene may affect the lipid profile of Brazilian children and adolescents and could contribute to the CVD in adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has received significant attention due to its status as a leading cause of mortality worldwide, with over 75% of cases occurring in low- and middle-income countries1. The burden of these diseases primarily attributes to cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs). Currently, the focus is not only on adults and older individuals but also on understanding the prevalence of these risk factors in younger groups2. Among the CVRFs, changes in serum lipid and lipoprotein levels are conditions that can lead to atherosclerotic vascular changes and ultimately result in CVD. Furthermore, atherosclerotic vascular changes can begin in childhood, creating an ideal setting for CVD events in adulthood2,3.

While most children have minimal atherosclerotic vascular changes that can be avoided or reduced by adhering to a healthy lifestyle, identifiable risk factors such as obesity, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and arterial hypertension accelerate the process in some children4,5. Therefore, prevention and early intervention of these risk factors can significantly impact the prevalence of CVD in adult life6.

Science has made continuous advancements in understanding the genetic underpinnings of complex human illnesses and the clinical and biochemistry of CVRFs7,8. In the general population, genetic variation accounts for 43–83% of the variability in plasma lipid levels9. In addition, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified genetic variants significantly associated with metabolism and lipid profiles10,11. The apolipoprotein B (APOB) gene has been a significant focus of genetic studies since the 1980s12. The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) XbaI (rs693 or C7673T) occurs in exon 26 of the APOB gene, replacing a cytosine (C) with thymine (T) (C/T – REV). This substitution results in a change from the codon ACC to ACT. Although this modification does not alter the amino acid sequence, researchers in Brazil and other populations suggest that this SNP influences the increase in total cholesterol (TC) concentrations in circulation12,13,14,15,16.

Given its central role in lipid transport and metabolism, examining the variations of the APOB gene could help explain some of the interindividual variation in lipid levels in young individuals and identify possible groups that require more prominent care to avoid cardiovascular problems in adulthood. The analysis in children and adolescents fills a knowledge gap, considering that the genetic implications in cardiovascular health from an early age are little explored. The choice stands out for the search to overcome possible limitations of previous studies and for the prospect of identifying relevant clinical implications for long-term prevention, since, with the advent of precision medicine, it is increasingly important to understand the genetic variations predisposing cardiovascular risk to individualize diagnosis and treatment.

Ouro Preto has studied its adult and child population over the years, and the data show a high prevalence of dyslipidemia and other risk factors such as excess weight17,18,19,20. Furthermore, current lifestyles have left children and adolescents with a greater tendency towards sedentary21. This study hypothesizes that the group with the highest number of CVRFs simultaneously with a risk genotype for the XbaI polymorphism in the APOB gene, will present a higher prevalence of increased TC when compared to wild-type homozygotes. Thus, considering that there are few Brazilian studies on genetic risk factors for dyslipidemia in young people, this study aims to evaluate the association of XbaI polymorphism with cholesterol levels in children and adolescents in Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Methods

Study design and population

A population-based cross-sectional study was conducted with school-aged children and adolescents aged 6 to 17 in Ouro Preto, a small city located in southeastern Brazil, in the state of Minas Gerais, between April and December 2021. The eligibility criteria were: the student must have been enrolled in primary education at a school in Ouro Preto and the person responsible for the student being interviewed must be over eighteen years old and live in the same household as the student. The exclusion criteria were: pregnant teenagers, students of Youth and Adult Education Program and the Association of Parents and Friends of the Exceptional.

Sampling plan

A stratified sample size for the population survey was determined based on four parameters: (1) The proportion of the population in the studied age group with overweight and obesity (14.9%)18; (2) The number (4,864) and proportion of students enrolled in each public and private elementary school in Ouro Preto; (3) A margin of error of 3%; and (4) A confidence level of 95%. The sample calculation determined a minimum sample size of 876. To account for potential losses due to non-adherence to the research or non-collection of blood samples, the researchers inflated the sample by 20%, resulting in the initial evaluation of a sample of 1,051 individuals in the study. We obtained the participation of 912 students, exceeding the minimum calculated sample size, thus preserving the statistical power required for the study. The selection was carried out in a simple random way, without replacement, from the list of students enrolled in 2021. Then, the researchers contacted the parents of the students by telephone and invited them to participate in the research. Three contact attempts were made before the student was excluded from the draw. In case of refusal, the next student of the same sex on the attendance list was drawn.

Data collection

Data collection consisted of the following steps: (1) a face-to-face interview with the student’s legal guardians, who answered a questionnaire about the student’s sociodemographic, behavioral, and clinical data (2) a physical examination consisting of weight and height measurements and (3) blood tests for biochemical, such as TC and fractions, triglycerides (TG) and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and molecular (SNP) evaluations.

Questionnaire

Sociodemographic

Included data such as gender, age, skin color, school (public or private), family income (in minimum wages), receipt of government social benefits, and the schooling of the chief of the family. In 2021, the minimum wage was approximately 207 dollars. With the exception of skin color, which was self-reported, it was parents who reported characteristics of their children by face-to-face interview.

Behavioral

The evaluation assessed screen time, considering it increased when it exceeded 2 h per day for children and 3 h per day for adolescents. Furthermore, passive smoking was considered if the children or adolescents lived with a smoker.

Clinical

Neonatal history (gestational age and birth weight) and family history of obesity or dyslipidemia were questioned.

Anthropometric parameters

Weight

Weight was measured on a Tanita Ironman InnerScan® digital anthropometric scale in an orthostatic position, wearing light clothing and without shoes.

Height

Height was measured with a Sanny® field stadiometer, graduated in millimeters (mm), with the student standing with his back to the marker, with bare feet together, in an orthostatic position, and looking straight ahead.

Body mass index (BMI)

BMI was calculated by weight (in kilogram) divided by height squared (in meters), being classified as eutrophic (if BMI/age ≤ + 1 in the Z-score) or excess weight (if BMI/age > + 1 in the Z-score), according to World Health Organization standards22.

Biochemical and molecular analysis

For the biochemical analysis, the participant was in a stable metabolic state with the usual diet state, and, as recommended for the child population, fasting was not required23,24.

Glycated hemoglobin

Following the manufacturer’s protocol, the HbA1c level was measured using the immunoturbidimetry method on the Cobas Integra 400 plus® automatic analyzer (Roche, Germany). The HbA1c level was classified as normal (if < 5.7%) or high (if ≥ 5.7%)25.

Lipid profile

The serum concentration of TG, TC, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were measured using the enzymatic-colorimetric method (Triglicérides monoreagent®, Cholesterol monoreagent®, HDL Direto®, Bioclin/Quibasa, Brazil) and evaluated using the Chemwell R6® Automated Analyzer, Awareness Technology. The Friedewald formula was used to calculate the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol fraction: LDL (mg/dL) = (TC-HDL) - (TG/5), applicable when the concentration of TG is ≤ 400 mg/dL26. The classification of dyslipidemia followed the criteria of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology27, which considers a normal value for TC < 170 mg/dL, LDL < 110 mg/dL, HDL > 45 mg/dL, and TG < 85 mg/dL (from 0 to 9 years old) and < 100 mg/dL (from 10 to 19 years old).

Molecular analysis

Genomic DNA extraction was performed using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega®) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The XbaI polymorphism, SNP type, was chosen based on the following criteria: (1) positive association with dyslipidemia in previous studies, including GWAS, in similar ethnic groups as the study population28,29,30,31,32; and (2) absence of rare alleles in studies with African and European populations. The allele and genotype frequencies were evaluated and tested for the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium. The allelic discrimination technique was performed using real-time PCR and a set of primers and probes specific for each SNP (TaqMan® Minor Groove Binder-MGB, TaqMan® System; 7500 fast Real-Time PCR Systems, Applied Biosystems).

Exposure, outcome, and covariables

XbaI polymorphism was evaluated as exposure, increased serum levels of TC were considered the outcome, and sociodemographic, behavioral, clinical, anthropometric, and biochemical variables were covariables.

Statistical analysis

The database was built and analyzed using SPSS® version 28 software. The study population was characterized through bivariate analysis, where the study variables were categorized and presented as relative frequencies. Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used for differences in these groups. The allele frequencies were obtained by gene counting and tested for the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

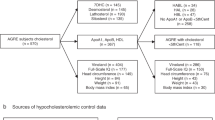

Logistic regression was performed to verify the association between polymorphism and increased TC in children and adolescents. A theoretical causality model based on a directed acyclic graph (DAG) was developed to guide the analysis models (Fig. 1). The DAG was constructed according to the exposure variable (polymorphism), outcome (increased TC), and covariates using the online software Dagitty®, version 3.2. To avoid unnecessary adjustments, spurious associations, and estimation errors, the backdoor criterion was used to select a minimum set of confounding variables to fit the analyses33. Therefore, the model was adjusted by the following minimum and sufficient set of variables: age, birth weight, gestational weight, family income, skin color, and glycemic profile. Moreover, unadjusted and adjusted logistic regressions were performed for the variables indicated by DAG. The variance inflation factor assesses collinearity between covariates with the “subsetByVIF” package considering a maximum cutoff point of 10 (VIF < 10)34,35.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Federal University of Ouro Preto (CAAE 28680020.0.0000.5150).

Results

From a sample of 912 students, 57.0% were adolescents (10–17 years) and 50.2% were male. For children and adolescents, the median age was 7 (IQR: 6–8) and 12 (IQR: 11–14) years, respectively. For the outcome variable, 68.9% of participants had increased TC. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics of individuals with normal and increased TC levels. The analysis reveals that children from private schools, with a higher level of education of the head of the family, and with a family history of dyslipidemia had a higher chance of presenting increased TC (p < 0.05).

The XbaI polymorphism was consistent with the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (p = 0.854). The frequency of the C allele and T allele were 66.4% and 33.6%, respectively (data not shown in tables). Table 2 presents biochemical characteristics related to XbaI polymorphism genotypes in children and adolescents. Although not significant, there was a tendency towards an increase in TC levels in carriers of the T allele.

Table 3 presents the association between individual genotypes and a combination based on a dominant and recessive model of the XbaI polymorphism with TC. In the dominant model, individuals homozygous for the T allele had a 1.44 times greater chance, and those carrying at least one T allele had a 1.45 times greater chance of presenting increased TC. In the recessive model, when comparing the TT genotype with the CC + CT genotypes, no statistically significant associations were found between the TT genotype and the augmented ratio chance of increased TC. These results indicate that the presence of the T allele raises the ratio chance of increased TC only when in heterozygosity or homozygosity (CT + TT) and that the recessive model (TT) does not influence the chance in isolation.

Figure 2 shows the risk modification between the XbaI polymorphism in the APOB gene and clinical variables with TC in children and adolescents. It was observed that individuals with the CT/TT genotype of the XbaI polymorphism had a higher chance of having increased TC than individuals with the CC genotype (OR: 1.45; 95% CI: 1.09–1.94, p = 0.011). This chance was further increased when the CT/TT genotype was associated with being excess weight (OR: 1.74; 95% CI: 1.11–2.71, p = 0.015) or having a family history of dyslipidemia (OR: 2.04; 95% CI: 1.14–3.67, p = 0.016). These results suggest that the XbaI polymorphism may interact with clinical and family factors to enhance the risk of increased TC in children and adolescents.

Discussion

The present study evaluated the association between XbaI polymorphism and increased cholesterol in children and adolescents from Ouro Preto, Brazil. In a dominant model, carriers of the variant T allele, after adjustment, showed a significant interaction between excess weight and a family history of dyslipidemia with XbaI polymorphism in increased TC. Until now, this is one of the initial research studies to assess the XbaI polymorphism in the APOB gene among children and adolescents in Brazil.

In this study, we found a prevalence of increased TC in children and adolescents in Ouro Preto, higher than the national average (27.5–33.0%)36,37 and other regions of Brazil38,39,40. This prevalence is also higher than that reported in other countries, such as Qatar (27.0%)41 and the United States (7.1%)42. Genetic, environmental, or methodological factors can explain these differences. For example, the XbaI polymorphism in the APOB gene may be more frequent in the Ouro Preto population than in other populations, conferring a greater susceptibility to increased cholesterol. In addition, environmental factors such as inadequate diet, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity may contribute to increased plasma cholesterol in this population. Another possibility is that methodological differences between studies, such as diagnostic criteria, laboratory techniques, and statistical adjustments, may influence the estimate of the prevalence of increased cholesterol, reflecting the diversity in lipid profiles between different populations. The importance of considering population contexts when interpreting lipid levels in children and adolescents is highlighted. In the case of this study, the cutoff points recommended by the Brazilian Society of Cardiology27 were used, as they are widely used in the Brazilian pediatric population, which facilitates understanding in the context of public health in Brazil. In any case, the importance of additional studies to evaluate possible variations in specific subgroups within the Brazilian population is emphasized.

One of the genes closely monitored for its potential effect on lipid metabolism is the APOB gene. The isoform apoB100, synthesized in the liver, is primarily secreted in very-low-density lipoprotein particles, which are then cleaved by lipase enzyme and converted into intermediate-density lipoprotein and subsequently into LDL, which is gradually metabolized43. The presence of apoB100 in LDL is essential for facilitating the entry of cholesterol into peripheral cells through its binding to LDL receptors on the surface of these cells. This receptor-dependent binding is intrinsically related to the accumulation of cholesterol in arteries. Therefore, an excess of apoB100, possibly influenced by the XbaI polymorphism, represents a triggering factor for the atherogenic process43.

Studies have shown a positive association between the XbaI polymorphism and TC, TG, apoB100, and LDL levels and a negative association with HDL28,29,30,31,32. Following the present study, a recent meta-analysis showed that carriers of the “T” allele had high plasma concentrations of TC42. Furthermore, the same study also observed elevated levels of apoB100, TG, LDL, and low HDL compared to non-carriers of this allele32.

In addition to the dominant model, the analysis using the recessive model allowed a broader view of the genetic associations with increased TC. As expected based on previous studies12,13,14,28,29,30,31,−32,44, the T allele is considered a risk allele, and its presence in the CT + TT genotypes was associated with an augmented risk for increased TC. However, our results show that, in the recessive model (TT versus CC + CT), there was no significant difference in risk, suggesting that the effect of the T allele is dependent on the presence of at least one additional copy of the C allele to modify the phenotype of risk.

These findings corroborate the complexity of gene-environment interactions and reinforce the need to investigate different genetic models to better understand variations in the risk of dyslipidemia. The presence of the T allele in a context of heterozygosity appears to be sufficient to influence lipid levels, which may have implications for preventive strategies in genetically predisposed populations.

However, increased TC in children and adolescents is a highly complex phenotype, influenced not only by individual genetic variants but also by interactions between multiple genes and environmental factors. These variables interact in a complex way and often show varying patterns among different populations and age groups, which contributes to the wide range of results found in the literature on genetics and lipids9,10,11. In the present study, despite the significant association observed between the XbaI polymorphism in the APOB gene and increased TC, it is recognized that other genetic and environmental factors also play determining roles in lipid levels, which were not controlled in our design. Therefore, it is essential to interpret our findings with caution, understanding that they reflect a relationship observed within a multifactorial and complex context, where other relevant factors can significantly influence the lipid profile.

The presence of the T allele has been extensively studied since the late 1980s in African, Caucasian, and Asian populations regarding the risk for coronary heart disease through generalized or regional adiposity and LDL, TC, and TG fractions12,13,14,44. Similarly, studies with Brazilian adults point to the same results30,31,45. However, in some studies, the results are still conflicting46,47,48. In addition to the influence of ethnicity, the need for more consistency between studies reflects other limitations, such as sample size and methodology adopted.

In the Brazilian population, the study by Alves et al.15 showed in older people a significant association between the XbaI polymorphism and serum TC, LDL, and total lipid levels, with essential elevations among T homozygotes compared to the other genotypes. Once again, it corroborated that genetic variations in the APOB gene affected the lipemic profile of the Brazilian population. Few studies have described results in children. Hu et al.49 observed in Chinese children that the XbaI polymorphism was associated with higher BMI and serum levels of Lipoprotein (a), TC, TG, LDL, and apoB100.

The current study demonstrates that combined with clinical factors, detecting carriers of the risk allele may be an essential tool for detecting groups susceptible to dyslipidemia and requiring a follow-up. Given the sedentary lifestyle adopted by children and adolescents, united with the impact of the Coronavirus 2019 pandemic, there has been an increase in screen time21, which is a factor associated with dyslipidemia in this age group50,51. Sedentary time is spent in activities that involve low energy expenditure, such as watching television, playing video games, or using a computer or cell phone. These activities may favor consuming caloric foods and impair sleep quality, contributing to lipid imbalance52. For instance, childhood obesity is associated with CVRFs such as dyslipidemia, which is linked to accelerated atherosclerosis in this age group53. Therefore, when combined with genetic factors such as XbaI polymorphism, it becomes relevant to understand these factors’ impact on young people’s cardiovascular health.

This study is substantial because it evaluated genetic CVRFs in young populations, which is not often seen in studies conducted in Brazil. In addition, the sample was representative, allowing for the estimation of the prevalence of the risk factors studied and ensuring the study’s external validity. However, the study had limitations. First, the cross-sectional design did not allow any causal inferences between exposure factors and increased TC. Second, the study did not assess three crucial factors that could affect lipid parameters: physical activity levels, the participants’ dietary patterns, and the pubertal stage, which can significantly influence lipid levels, especially in adolescents. Although these factors are relevant, the data were collected during the peak of the Coronavirus 2019 pandemic, when drastic lifestyle changes — including reduced school attendance and the level of physical activity54,55, and increased food insecurity54,56 — made it challenging to gather accurate information on lifestyle habits. Additionally, a DAG model was used to identify and control for a minimal set of confounding variables, which excluded these factors from the final analysis to prevent over-adjustment and estimation errors. This limitation suggests that the increased TC observed in this study should be interpreted cautiously, since such factors may individually impact lipid levels in children and adolescents.

In conclusion, our results support the idea that XbaI polymorphism in the APOB gene can affect the cholesterol levels of Brazilian children and adolescents living in urban conditions and may contribute to atherosclerosis. Considering the heterogeneity in the literature and the fact that cholesterol levels results from complex interactions between genes and the environment, we recommend conducting additional studies to determine the physiological effects of allelic variations in the APOB gene, mainly the XbaI polymorphism, in the context of their interactions with environmental factors.

Data availability

The data and materials are available and can be provided by the corresponding author based on reasonable request and a study protocol.

References

World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) - Newsroom Facts Sheet Detail. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (2021).

Jacobs, D. R. et al. Childhood cardiovascular risk factors and adult cardiovascular events. N Engl. J. Med. 386, 1877–1888. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2109191 (2022).

Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health. Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics 128(Supl5), S213–S256. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2107C (2011).

American Academy of Pediatrics. Cardiovascular risk reduction in high-risk pediatric populations. Pediatrics 119(3), 618–621. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-3557 (2007).

de Ferranti, S. D. et al. Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in High-Risk Pediatric Patients: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 139, e603–e634. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000618 (2019).

Bloch, K. V. et al. The Study of Cardiovascular Risk in Adolescents–ERICA: rationale, design and sample characteristics of a national survey examining cardiovascular risk factor profile in Brazilian adolescents. BMC Public. Health 15, 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1442-x (2015).

Kathiresan, S. & Srivastava, D. Genetics of human cardiovascular disease. Cell 148(6), 1242–1257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.001 (2012).

Cox, A. J. et al. Genetic risk score associations with cardiovascular disease and mortality in the Diabetes Heart Study. Diabetes Care 37(4), 1157–1164. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-1514 (2014).

Chang, M. H., Yesupriya, A., Ned, R. M., Muellerm, P. W. & Dowling, N. F. Genetic variants associated with fasting blood lipids in the U.S. population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. BMC Med. Genet. 11, 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-11-62 (2010).

Kathiresan, S. et al. A genome-wide association study for blood lipid phenotypes in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med. Genet. 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S17 (2007).

Kathiresan, S. et al. Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat. Genet. 41, 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.291 (2009).

Rajput-Williams, J. et al. Variation of apolipoprotein-B gene is associated with obesity, high blood cholesterol levels, and increased risk of coronary heart disease. Lancet 332, 8626–8627. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90930-0 (1988).

Kathiresan, S. et al. Polymorphisms associated with cholesterol and risk of cardiovascular events. N Engl. J. Med. 358, 1240–1249. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0706728 (2008).

Deo, R. C. et al. Genetic differences between the determinants of lipid profile phenotypes in African and European Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. PLoS Genet. 5(1), e1000342. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000342 (2009).

Alves, E. et al. The APOB rs693 polymorphism impacts the lipid profile of Brazilian older adults. Braz J. Med. Biol. Res. 53(3), e9102. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431X20199102 (2020).

Machado, M. O., Hirata, M. H., Bertolami, M. C. & Hirata, R. D. Apo B gene haplotype is associated with lipid profile of higher risk for coronary heart disease in Caucasian Brazilian men. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 15(1), 19–24 (2001).

Cândido, A. P. et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a risk factor associated with ischemic heart disease: Ouro Preto Study. Atherosclerosis 191(2), P454–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.04.031 (2007).

Cândido, A. P. et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in children and adolescents living in an urban area of Southeast of Brazil: Ouro Preto Study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 168, 1373–1382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-009-0940-1 (2009).

Batista, A. P. et al. High levels of chemerin associated with variants in the NOS3 and APOB genes in rural populations of Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Braz J. Med. Biol. Res. 53(6), e9113. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431X20209113 (2020).

Batista, A. P. et al. Hypertension is associated with a variant in the RARRES2 gene in populations of Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais, Brazil: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Genet. 12(3), 40–51 (2021).

Okely, A. D., Kontsevaya, A., Ng, J. & Abdeta, C. 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behavior. Sports Med. Health Sci. 3(2), 115–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smhs.2021.05.001 (2021).

World Health Organization. The WHO Child Growth Standards tools and toolkits Child growth standards. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/toolkits/child-growth-standards/standards (2006/2007).

Steiner, M. J., Skinner, A. C. & Perrin, E. M. Fasting might not be necessary before lipid screening: a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Pediatrics 128(3), 463–470. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0844 (2011).

Nordestgaard, B. G. et al. Fasting Is Not Routinely Required for Determination of a Lipid Profile: Clinical and Laboratory Implications Including Flagging at Desirable Concentration Cutpoints-A Joint Consensus Statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society and European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Clin. Chem. 62(7), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2016.258897 (2016).

American Diabetes Association. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 43(Supl1). https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-S002 (2020). S14-S31.

Friedewald, W. T., Levy, R. I. & Fredrickson, D. S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 18(6), 499–502 (1972).

Faludi, A. A. et al. Atualização da Diretriz Brasileira de Dislipidemias e Prevenção da Aterosclerose –. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 109(2 Supl1), 1–76. https://doi.org/10.5935/abc.20170121 (2017).

Saxena, R. et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science 316(5829), 1331–1336. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1142358 (2007).

Povel, C. M. et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) involved in insulin resistance, weight regulation, lipid metabolism and inflammation in relation to metabolic syndrome: an epidemiological study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 11, 133. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-11-133 (2012).

Lazzaretti, R. K. et al. Genetic markers associated to dyslipidemia in HIV-infected individuals on HAART. Sci. World J. 608415. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/608415 (2013).

Rodrigues, A. C. et al. Genetic variants in genes related to lipid metabolism and atherosclerosis, dyslipidemia and atorvastatin response. Clin. Chim. Acta 417, 8–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2012.11.028 (2013).

Niu, C. et al. Associations of the APOB rs693 and rs17240441 polymorphisms with plasma APOB and lipid levels: a meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-017-0558-7 (2017).

Cortes, T. R., Faerstein, E. & Struchiner, C. J. Use of causal diagrams in Epidemiology: application to a situation with confounding. Cad Saude Publica 32(8), e00103115. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00103115 (2016).

Hair, J. F. Multivariate data analysis an overview in International encyclopedia of statistical science (ed Lovric, M.) 904–907 (Springer Berlin, 2011).

Plummer, W. & Dupont, W. D. SUBSETBYVIF: Stata module to select a subset of covariates constrained by VIF. Econ. Papers. https://econpapers.repec.org/software/bocbocode/s458635.htm (2019).

da Silva, T. P. R., Mendes, L. L., Barreto, V. M. J., Matozinhos, F. P. & Duarte, C. K. Total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein alterations in children and adolescents from Brazil: a prevalence meta-analysis. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 67(1), 19–44. https://doi.org/10.20945/2359-3997000000508 (2023).

Gomes, E., Zago, V. H. S. & Faria, E. C. Evaluation of Lipid Profiles of Children and Youth from Basic Health Units in Campinas, SP, Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Laboratory Study. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 114(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.5935/abc.20190209 (2020).

Bezerra, M. K. A. et al. Health promotion initiatives at school related to overweight, insulin resistance, hypertension and dyslipidemia in adolescents: a cross-sectional study in Recife, Brazil. BMC Public. Health 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5121-6 (2018).

Vizentin, N. P. et al. Dyslipidemia in Adolescents Seen in a University Hospital in the city of Rio de Janeiro/Brazil: Prevalence and Association. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 112(2), 147–151. https://doi.org/10.5935/abc.20180254 (2019).

Gomes, E. I. L., Zago, V. H. S. & Faria, E. C. Evaluation of Lipid Profiles of Children and Youth from Basic Health Units in Campinas, SP, Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Laboratory Study. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 114(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.5935/abc.20190209 (2020).

Rizk, N. M. & Yousef, M. Association of lipid profile and waist circumference as cardiovascular risk factors for overweight and obesity among school children in Qatar. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 5, 425–432. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S39189 (2012).

Perak, A. M. et al. Trends in Levels of Lipids and Apolipoprotein B in US Youths Aged 6 to 19 Years, 1999–2016. JAMA 321(19), 1895. (1905). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.4984 (2019).

National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 106(25), 3143–3421 (2002).

Chasman, D. I. et al. Genetic loci associated with plasma concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, apolipoprotein A1, and Apolipoprotein B among 6382 white women in genome-wide analysis with replication. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 1, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.773168 (2008).

Salazar, L. A. et al. Seven DNA polymorphisms at the candidate genes of atherosclerosis in Brazilian women with angiographically documented coronary artery disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 300(1–2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-8981(00)00308-9 (2020).

Sakuma, T., Hirata, R. D. & Hirata, M. H. Five polymorphisms in gene candidates for cardiovascular disease in Afro-Brazilian individuals. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 18, 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.20044 (2004).

Nakazone, M. A. et al. Effects of APOE, APOB and LDLR variants on serum lipids and lack of association with xanthelasma in individuals from Southeastern Brazil. Genet. Mol. Biol. 32(2), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-47572009005000028 (2009).

Bogari, N. M., Abdel-Latif, A. M., Hassan, M. A., Ramadan, A. & Fawzy, A. No association of apolipoprotein B gene polymorphism and blood lipids in obese Egyptian subjects. J. Negat. Results Biomed. 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12952-015-0026-8 (2015).

Hu, P. et al. Effect of apolipoprotein B polymorphism on body mass index, serum protein and lipid profiles in children of Guangxi, China. Ann. Hum. Biol. 6(4), 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014460902882475 (2009).

Sina, E. et al. Media use trajectories and risk of metabolic syndrome in European children and adolescents: the IDEFICS/I.Family cohort. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 18, 134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01186-9 (2021).

Manousaki, D. et al. Tune out and turn in: the influence of television viewing and sleep on lipid profiles in children. Int. J. Obes. 44, 1173–1184. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-020-0527-5 (2020).

Schefelker, J. M. & Peterson, A. L. Screening and Management of Dyslipidemia in Children and Adolescents. J. Clin. Med. 11(21), 6479. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216479 (2022).

Cook, S. & Kavey, R. E. Dyslipidemia and pediatric obesity. Pediatr. Clin. North. Am. 58(6), 1363–1373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2011.09.003 (2011).

Rundle, A. G., Park, Y., Herbstman, J. B., Kinsey, E. W. & Wang, Y. C. COVID-19-related school closings and risk of weight gain among children. Obesity 28(6), 1008–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22813 (2020).

Hall, G., Laddu, D. R., Phillips, S. A., Lavie, C. J. & Arena, R. A tale of two pandemics: How will COVID-19 and global trends in physical inactivity and sedentary behavior affect one another? Prog Cardiovasc. Dis. 64, 108–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.005 (2021).

Ng, Y. et al. Food Insecurity During the First Year of COVID-19: Employment and Sociodemographic Factors Among Participants in the CHASING COVID Cohort Study. Public. Health Rep. 138(4), 671–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549231170203 (2023).

Acknowledgements

To all members of the Coraçõezinhos de Ouro Preto group.

Funding

FAPEMIG (APQ-01933-21) supported this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.V.S. and G.L.L.M.C. conceptualized and designed the study, A.P.B. carried out the biochemical and molecular analyses, A.C.M.C., C.F.L., L.G.L., W.W.O., M.C.L., M.A.M.A., I.V.D.B., A.C.S.S. and R.L.G. field data collection and manuscript review for important intellectual content, T.V.S., A.P.B., L.A.A.M.J. and G.L.L.M.C. carried out the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript (original draft). All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Federal University of Ouro Preto (CAAE 28680020.0.0000.5150).

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and written informed consent was obtained from the parents.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Souza, T.V., Batista, A.P., de Menezes-Júnior, L.A.A. et al. XbaI polymorphism in the APOB gene and its association with increased cholesterol in children and adolescents: Ouro Preto study. Sci Rep 14, 31452 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83099-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83099-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

FTO and NOS3 genes associated with pediatric obesity: Corações de Ouro Preto study

BMC Pediatrics (2025)