Abstract

This study delves into the challenges posed by the low-temperature calcination of high-ferrite Portland cement (HFPC) clinker and explores the potential of boron oxide (B2O3) as a stabilizing agent. Clinker production is a major contributor to global carbon dioxide emissions, and finding sustainable solutions is paramount. At 1350 °C, the HFPC clinker exhibits severe pulverization due to the metastable nature of the C2S phase formed at low temperature. To address these challenges, various stabilizing agents, including K2O + Na2O, barium carbonate (BaCO3), calcium fluoride (CaF2), and B2O3, were investigated. K2O + Na2O, BaCO3, and B2O3 exhibited promising stabilization effects, although K2O + Na2O negatively impacted the stability, and BaCO3 resulted in significant retardation. Consequently, B2O3 was chosen as the preferred stabilizing agent for the low-temperature calcination of HFPC clinker. However, it was observed that the B2O3 content should not exceed 1% to prevent destabilization of the C3S phase, which affects early-stage strength development. This research contributes to the understanding of HFPC clinker stability under low-temperature conditions and provides a potential avenue for reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions in HFPC clinker production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, countries worldwide have actively committed to addressing the impacts of climate change by adopting innovative and coordinated approaches to development. Such initiatives aim to accelerate the transition toward sustainable development and promote environmentally conscious lifestyles1,2. The concentration of atmospheric CO2 has undergone a notable increase, rising from approximately 285 parts per million (ppm) in the year 1850 to 410 ppm in 2019. Concurrently, the Earth’s global surface temperature exhibited a rise of 1.07 K (K) during the decade of 2010–2019 when compared to the period of 1850–19003. This temperature escalation presents a significant and imminent threat to life on our planet4. To constrain the global temperature increase to 1.5 K above pre-industrial levels, it is imperative that global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions be curtailed by approximately 45% by the year 2030 to the emissions recorded in 2010, and achieve net-zero emissions on a global scale around the year 20505.

Among the many contributors to CO2 emissions, the cement industry undoubtedly stands as the largest global source of CO2 emissions, accounting for nearly 8% of global CO2 emissions6. That means approximately 0.5–0.7 tons of CO2 are released for every ton of Portland cement (PC) produced7. The global Portland cement production reached a staggering 4.1 × 1012 kg in 2020, with China contributing approximately 54% of this total8, and this production figure is expected to surge to around 6.0 × 1012 kg by the year 20509. Despite China’s recent efforts and policies aimed at reducing CO2 emissions, the overall emissions remain enormous.

The fundamental reasons behind the persistently high carbon dioxide emissions and energy consumption issues in the cement industry are rooted in the high temperature sintering characteristics of the mineral phases in traditional PC clinker. Traditional PC clinker primarily consists of tricalcium silicate (C3S: 55–70%), dicalcium silicate (C2S: 18–25%), tricalcium aluminate (C3A: 5–12%), and tetracalcium aluminoferrite (C4AF: 5–15%)10,11. Among these, tricalcium silicate is the most important mineral phase in ordinary Portland cement and the primary contributor to the mechanical properties of cement matrices12. Compared to the other three mineral phases, the formation of the C3S phase requires a higher synthesis temperature (1450 °C) and greater consumption of limestone13, which consequently leads to the high energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions in the production of traditional PC clinker. To fundamentally address the issue of carbon dioxide reduction in the cement industry, there is a need for a specific adjustment of the mineral phase composition of PC clinker to develop green and energy-efficient cementitious materials.

Based on this, high-ferrite Portland cement (HFPC) clinker has emerged14,15, characterized by a low C3S content and a high C4AF content, thus having a lower sintering temperature (1400 °C) compared to traditional PC clinker. Theoretical analysis indicates that the sintering temperature of HFPC clinker can be further reduced to 1350 °C16. However, at this temperature, serious pulverization occurs in the HFPC clinker, significantly affecting its hydration performance. Considering the excellent performance of HFPC clinker and the energy-saving advantages of its low-temperature preparation, investigating the stabilizing technology for HFPC clinker at the lowered sintering temperature is of utmost importance and research value.

In the extensive research on PC clinker stability, the primary approach used is the addition of different stabilizers to ensure the mineral phases exist in a more stable form17. Currently, commonly used stabilizers include K2O, Na2O, BaO and B2O3, among others18,19,20. These stabilizers primarily increase the liquid phase content in the PC clinker to achieve its stability. The mineral composition of HFPC clinker differs from traditional PC cement, therefore this study investigates the influence of several oxide stabilizers on the stability of HFPC clinker at the lowered sintering temperature.

Materials and methods

Materials

The raw materials used in this study, including CaO, Al2O3, SiO2, Fe2O3, B2O3, BaCO3, Ba(NO3)2, Na2CO3, K2CO3, CaF2, are analytical grade reagents. The preparation and sintering process of HFPC clinker refers to Zhang et al.16, and the sintering temperature is controlled at 1350 ℃. Table 1 shows chemical and mineral compositions of the HFPC clinker. The added type and ratios of stabilizers are shown in Table 2.

Methods

The test method of free lime (f-CaO) is strictly implemented in accordance with reference21. The crystal structural of different HFPC clinker was ascertained utilizing a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (XRD), employing Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 0.15046 nm) and ranging from 10 to 60°, with increments of 1° per minute. The analysis of X-ray diffraction (XRD) data for the determination of phase content in all clinkers was performed using Topas software. The latest version is Topas V622. The refinement of Rietveld parameters, which encompassed background coefficients, cell parameters, zero-shift error, peak shape parameters, preferred orientation, and phase fractions, was carried out. The evolution of HFPC clinker hydration was characterized by isothermal calorimetry measurements at 20 ± 0.1℃ and the water to clinker ratio is kept at 0.5. For sample preparation of compressive strength, a specified amount of water was first added to the mixing pot, followed by sequentially adding different HFPC clinker. The mixture was processed in an automatic mixer with the following sequence: slow stirring for 120 s, a 15-second pause, and fast stirring for another 120 s. The well-mixed paste was then poured into 20 mm × 20 mm × 20 mm molds and vibrated for 2 min to remove air bubbles. The molds were covered with plastic film and placed in a standard curing box (RH > 95%, 20 ± 2 °C). After 24 h, the hardened samples were demolded and returned to the curing box for further curing until the specified age. The compressive strength of these samples was tested by the WYA-300 Automated Breaking and Compressive Resistance tester (Wuxi, China) at 3 d, 7 d and 28 d.

Results and discussion

Effect of stabilizer type on the sintering properties of HFPC clinker

According to results shown in the Table 3; Fig. 1, the pulverization phenomena is observed in HFPC clinker at 1350 °C, and the f-CaO content in HFPC clinker is only 0.24%. Consequently, the pulverization occurring in HFPC clinker is not a result of the decomposition of tricalcium silicate (C3S). Combining this with the percentage of C2S crystalline phases in the HFPC clinker under this temperature regime in the following section, it becomes apparent that the formation of γ-C2S is a result of a transformation from the α or β type of C2S crystalline phases23,24. The introduction of K2O + Na2O, BaCO3, and B2O3 effectively inhibits the occurrence of clinker pulverization phenomena, while the addition of CaF2 did not achieve clinker stability. However, the subsequent mechanical performance testing reveals that the sample doped with 1.5% Na2CO3 and 1% K2CO3 exhibits cracking at only one day curing age, associated with high content of f-CaO (5.41%). Consequently, the high f-CaO content in the samples led to the release of a significant amount of heat during early curing and the formation of a large quantity of calcium hydroxide, resulting in matrix expansion and rupture. Alkali metal oxides can reduce the melting point of silicate minerals, thereby promoting liquid phase reactions and reducing calcination temperatures. This will lead to oversintering of the HFPC clinker, causing more free lime to precipitate. Furthermore, 5% BaCO3 added sample exhibits good stability to HFPC clinker, but the sample mixed with water shows a significant delayed setting, and the mechanical strength test cannot be performed. In summary, based on the experiments, it was decided to select B2O3 for further investigation into the stability of pulverization in HFPC clinker.

Effect of stabilizer content on the sintering properties of HFPC

After the calcination of HFPC clinker, it was observed that different levels of B2O3 doping all played a favorable role in stabilizing the clinker, with no pulverization phenomena observed. Additionally, the f-CaO content at different B2O3 doping levels of HFPC clinker is found to be 0.26%, 0.29%, 3.99%, and 1.50% in Fig. 2. The results indicate that when the B2O3 doping level was below 1%, the resulting HFPC clinker exhibits a lower f-CaO content and better sinterability. However, when the doping level of B2O3 reached 1%, the f-CaO content surged to 3.99%. Generally, the f-CaO content in cement clinker should not exceed 1.50% under normal conditions, as exceeding this level can compromise the PC soundness. As the B2O3 content further increased to 2%, the f-CaO content decreased to 1.50%. When too much crystalline stabilizer of B2O3 is added, free lime will combine with metastable phase of α-C2S again, resulting in the regeneration of C3S25. This leads to a decrease in free lime and an increase of C3S phase.

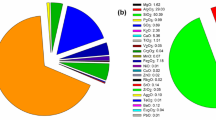

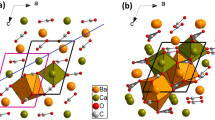

The mineral composition of HFPC clinker with different content of B2O3

XRD analysis was employed to investigate the mineral composition of HFPC clinker under varying B2O3 doping levels as seen in Fig. 3. It is evident that in samples with different B2O3 doping levels, the mineral phase of γ-C2S is hardly to be observed. Since the diffraction peaks of γ-C2S tend to overlap with other mineral phases. The main components of different samples are tricalcium silicate, dicalcium silicate, tricalcium aluminate, and tetracalcium aluminoferrite. Additionally, the 1% B2O3 sample exhibits a diffraction peak for CaO near 2θ = 54°, which is consistent with f-CaO test results. However, it is difficult to compare the changes of mineral phase composition from the XRD patterns. Therefore, the quantitative analysis of the sample’s mineral phases by adding 10% aluminum oxide to the samples is conducted.

The XRD quantitative analysis results reveal that when the B2O3 content exceeds 0.2%, the C3S content in the samples decreases, while the C2S content increases in Fig. 4. As B2O3 is a crystalline stabilizer, the introduction of boron ions into the crystal lattice of C2S, can stabilize α-C2S and β-C2S, thus inhibiting the transformation from γ-C2S to β-C2S. Boron substitutes silicon as tetrahedral borate anion, BO45−, for single-boron doping26,27. However, excess B2O3 causes β-C2S to transform into α-C2S. Simultaneously, we also observed changes in the crystalline phases of C2S formed in the samples under different B2O3 doping conditions. In the blank sample, C2S exists in three crystalline forms: α, β, and γ. However, except for the 0.2% B2O3-doped sample, as the B2O3 content increases, the α crystalline form of C2S in the samples gradually increases. When the B2O3 content reaches 2%, the α crystalline form constitutes approximately 80% of the C2S phase. Additionally, under high B2O3 doping conditions, the C3A content in the samples notably decreases.

Hydration performance of HFPC clinker with different B2O3 content

The hydration heat flow and accumulated heat curves of samples with different B2O3 doping levels are presented in the Fig. 5. It can be observed that when the B2O3 content is 0.2%, the hydration heat flow and accumulated heat curves are similar to those of the blank sample, indicating no significant impact. When the B2O3 content increases to 0.5%, the hydration heat flow rate of the sample does not change significantly, but the maximum heat release is slightly reduced. Combined with XRD results, the decrease in the maximum heat release is attributed to the reduction in the C3S content in the sample due to 0.5% B2O3 doping. When the B2O3 content is further increased to 1% and 2%, no significant heat release peaks are observed in the early stages of hydration reactions. In the sample with 2% B2O3 doping, a broader heat release peak is observed. The accumulated heat curves for samples with different B2O3 doping levels also show the varying impact of different doping levels on the hydration performance of the samples. The incorporation of B2O3 leads to a postponement to the hydration of HFPC clinker, and the postponement is significantly intensified as the dosage of B2O3 increases. The hydration retarding is also responsible for the substantial reduction in early compressive strength. However, the later compressive strength (28 d) is more important for Portland cement. The addition of B2O3 could significantly increase the later compressive strength of the specimen, indicating that the addition of B2O3 only delays the hydration process of HFPC clinker. Therefore, the B2O3 content in HFPC clinker should be limited to 0.5%.

Compressive strength of HFPC clinker with different B2O3 content

As shown in Fig. 6, it presents the compressive strength of HFPC clinker with different B2O3 doping levels at different age periods. From the compressive strength results, it can be concluded that the introduction of a low amount of B2O3 leads to slow early strength development in HFPC clinker but eventually demonstrates excellent compressive strength. Combined with the results of Fig. 2, the addition of 1% B2O3 results in a significant increase in f-CaO content (3.99%), which far exceeds the standard limit (1.5%). f-CaO leads to poor early stability of the hardening sample with the occurrence of severe expansion and cracking. It causes the specimen to be unable to maintain integrity, so the compressive strength could not be tested. Although the samples 1350 and 1350 − 0.2 have similar C3S content, the α-C2S and C3A content in sample 1350 is significantly higher than sample 1350 − 0.2. Both α-C2S and C3A are mineral phases with high early strength, therefore the sample 1350 shows higher mechanical strength in the early stage. The f-CaO content of HFPC clinker with the addition of 2% B2O3 is reduced to 1.50%, which makes the specimen have better stability and integrity. Although it faces severe retardation problems proved by heat flow results, the compressive strength can be obtained at 7 d. As hydration products continue to generate and fill the pores, it also has good mechanical strength at 28 days. Although the introduction of B2O3 can suppress pulverization in HFPC clinker and the samples show excellent later-stage mechanical performance, the slow development of early strength remains a critical issue limiting the application and development of HFPC clinker. The reason for the slow early strength development in HFPC clinker after B2O3 doping may be due to the stabilization of the C2S mineral phase crystalline structure, which also leads to the unstable presence of C3S. This results in the slow early strength development of the sample. Additionally, because the formation temperature of the C3S mineral phase is relatively high, there is a threshold for the formation of C3S in the clinker at 1350 °C, which also limits the development of its early performance.

Doping mechanism of B2O3 to HFPC clinker

To investigate the impact of B2O3 doping mechanism on the phase transformation of silicate phases in the minerals, experiments utilized first-principles calculations to simulate the formation energies of defects in C2S and M-type C3S with different levels of B2O3 doping. The formation energy (ΔE)13,28 of defects was calculated using following equation:

Where Edef and Eper represent the lattice energies of the crystal before and after phase doping, n is the number of B atoms introduced into the crystal, and µs and µi are the chemical potentials of the crystal after ion doping.

From the computational results in Fig. 7, it can be concluded that at a 0.5% doping level, the stability sequence of B2O3 in the three C2S phases is beta > alpha > gamma. At a 1.0% doping level, the stability sequence of B2O3 in the three C2S phases is alpha > beta > gamma. This suggests that B2O3 acts as a stabilizer for the high-temperature phases of C2S: a small amount of doping can stabilize the higher-temperature beta phase, while a higher doping concentration can stabilize the even higher-temperature alpha phase. Furthermore, at both 0.5% and 1.0% B2O3 doping levels, the formation energy of defects in the formed phases is negative, indicating that B2O3 solubility at these levels benefits the stability of the crystal29,30. However, as the doping concentration increases, it can be observed that the formation energy of defects per unit concentration increases significantly, suggesting that further increasing the B2O3 content will substantially weaken its stabilizing effect on the three crystal forms of C2S. It is expected that B2O3 doping exceeding 2% will be detrimental to the stability of C2S crystal phases. Comparing the effects of 0.5% and 1% B2O3 doping on the formation energy of defects in C3S, it is evident that when more B2O3 atoms are doped into the sample, the formation energy of defects in C3S decreases. This indicates that a high concentration of B2O3 doping can destabilize the structure of C3S. Experimental results also show that compared to cement clinker doped with 0.5% B2O3, the sample doped with 1% B2O3 has a reduced C3S content. In conclusion, different levels of B2O3 doping can alter the formation energy of defects in mineral phase structures, subsequently affecting the stability of crystal structures and ultimately leading to phase transformations in the minerals.

Conclusions

Based on the exploration of the mineral composition, crystal structure, hydration properties, and mechanical performance of HFPC clinker with different stabilizers, several conclusions can be drawn:

-

(1)

The cause of HFPC clinker pulverization at 1350 °C is that the C2S phase formed in the clinker at low temperatures is a metastable state with a large number of lattice defects and high surface energy, rendering its crystal structure unstable. Rapid cooling measures are insufficient to stabilize its crystal form, leading to a transformation into γ-C2S and resulting in volume expansion and pulverization.

-

(2)

K2O + Na2O, BaCO3, and B2O3 show effective stabilization for HFPC clinker. However, K2O + Na2O leads to poor stability, and BaCO3 causes significant retarding of HFPC clinker. Ultimately, B2O3 is chosen as the best stabilizer for the low-temperature calcination of HFPC clinker.

-

(3)

The HFPC clinker with addition of B2O3 content less than 1% shows satisfactory hydration reactivity and compressive strength, while the high level of B2O3 leads to increased f-CaO content and slow strength development to HFPC clinker, ascribed to the transformation of C2S crystalline form and the decreased generation of C3S.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Additional information is available to the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Pan, J. Building a Green Home and Persisting in Promoting the Building of a Community with a Shared Future for Mankind, In China‘s Global Vision for Ecological Civilization: Theoretical Construction and Practical Research on Building Ecological Civilization, J. Pan (eds) 137–154. (Springer, 2021).

Broto, V. C. Urban governance and the politics of climate change. World Dev. 93, 1–15 (2017).

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change, 2. (2021).

Nie, S. et al. Analysis of theoretical carbon dioxide emissions from cement production: Methodology and application. J. Clean. Prod. 334, 130270 (2022).

Allen, M. et al. Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 C (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2018).

Andrew, R. M. Global CO2 emissions from cement production. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10 (1), 195–217 (2018).

Wojtacha-Rychter, K. & Kucharski, P. Smolinski Conventional and Alternative Sources of Thermal Energy in the Production of Cement—An Impact on CO2 Emission. Energies 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/en14061539 (2021).

Andrew, R. & Peters, G. The Global Carbon Project’s fossil CO 2 Emissions Dataset: 2021 Release (CICERO Center for International Climate Research, 2021).

Scrivener, K. L., John, V. M. & Gartner, E. M. Eco-efficient cements: Potential economically viable solutions for a low-CO2 cement-based materials industry. Cem. Concr. Res. 114, 2–26 (2018).

Huang, X. et al. The effect of supplementary cementitious materials on the permeability of chloride in steam cured high-ferrite Portland cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 197, 99–106 (2019).

Lang, L., Chen, B. & Li, J. High-efficiency stabilization of dredged sediment using nano-modified and chemical-activated binary cement. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 15 (8), 2117–2131 (2023).

Kang, X. et al. Hydration of clinker phases in Portland cement in the presence of graphene oxide. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 34 (2), 04021425 (2022).

Zhu, J. et al. Revealing the substitution preference of zinc in ordinary Portland cement clinker phases: A study from experiments and DFT calculations. J. Hazard. Mater. 409, 124504 (2021).

Lv, X. et al. Hydration, microstructure characteristics, and mechanical properties of high-ferrite Portland cement in the presence of fly ash and phosphorus slag. Cem. Concr. Compos. 136, 104862 (2023).

Yang, H. M. et al. High-ferrite Portland cement with slag: Hydration, microstructure, and resistance to sulfate attack at elevated temperature. Cem. Concr. Compos. 130, 104560 (2022).

Zhang, K. et al. Development of high-ferrite cement: Toward green cement production. J. Clean. Prod. 327, 129487 (2021).

Duvallet, T. Y. et al. Production of α′H-belite-CSA cement at low firing temperatures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 134, 104820 (2022).

Li, C., Wu, M. & Yao, W. Effect of coupled B/Na and B/Ba doping on hydraulic properties of belite-ye’elimite-ferrite cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 208, 23–35 (2019).

Zea-Garcia, J. D. et al. Hydration activation of Alite-Belite-Ye’elimite cements by doping with boron. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8 (9), 3583–3590 (2020).

Morsli, K. et al. Mineralogical phase analysis of alkali and sulfate bearing belite rich laboratory clinkers. Cem. Concr. Res. 37 (5), 639–646 (2007).

Tang, Y. et al. Controlling the soundness of Portland cement clinker synthesized with solid wastes based on phase transition of MgNiO2. Cem. Concr. Res. 157, 106832 (2022).

XRD TOPAS V6 Flyer DOC-H88-EXS080 high.pdf. https://my.bruker.com/acton/attachment/2655/f-dabd52a4-fa85-4a1c-a259-56fa15d9281f/1/-/-/-/-/XRD%20TOPAS%20V6%20Flyer%20DOC-H88-EXS080%20high.pdf

Mumme, W. et al. Rietveld crystal structure refinement, crystal chemistry and calculated powder diffraction data for the polymorphs of dicalcium silicate and related phases. N. Jb. Min. Abh 169, 35–68 (1995).

Taylor Cement chemistry (Thomas Telford, 1997).

Wesselsky, A. & Jensen, O. M. Synthesis of pure Portland cement phases. Cem. Concr. Res. 39 (11), 973–980 (2009).

Cuesta, A. et al. Reactive belite stabilization mechanisms by boron-bearing dopants. Cem. Concr. Res. 42 (4), 598–606 (2012).

Koumpouri, D. & Angelopoulos, G. N. Effect of boron waste and boric acid addition on the production of low energy belite cement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 68, 1–8 (2016).

Zheng, M. J. et al. Energy barriers for point-defect reactions in 3 C-SiC. Phys. Rev. B 88 (5), 054105 (2013).

Tao, Y. et al. Comprehending the occupying preference of manganese substitution in crystalline cement clinker phases: A theoretical study. Cem. Concr. Res. 109, 19–29 (2018).

Huang, X. et al. Enhanced sulfate resistance: The importance of iron in aluminate hydrates. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7 (7), 6792–6801 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52370156 and 42007260).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiao Huang contributed to conceptualization, data curation, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, writing—original draft and writing—review & editing. Jinfang Zhang contributed to data curation, formal analysis and writing—review & editing. Kechang Zhang worked in software, methodology, validation, visualization and writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, X., Zhang, J. & Zhang, K. Effect of boron oxide on stability of high-ferrite Portland cement clinker in low-temperature calcination. Sci Rep 14, 31825 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83179-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83179-9