Abstract

Intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) has been used to guide radio-frequency catheter ablation (RFCA) for better catheter navigation and less radiation exposure in treating atrial fibrillation (AF). This retrospective cohort study enrolled 227 AF patients undergoing ICE- or traditional fluoroscopy (TF)-guided RFCA for AF in a tertiary hospital. ICE was used more often in patients with atrial tachycardia [odds ratio (OR) 3.692, p = 0.062], a higher score of Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly, Drugs/alcohol concomitantly (OR 1.541, p = 0.050), or heart failure (OR 2.098, p = 0.156). Based on the comparisons of 47 propensity score-matched pairs from 156 patients only undergoing pulmonary vein isolation (PVI), patients using ICE exhibited a significantly higher success rate in the first transseptal puncture (100% vs. 87.2%, p = 0.041) and less radiation exposure [utilization of radiographic contrast agent (2.7 ml vs. 6.0 ml, p < 0.001), fluoroscopy time (5.7 min vs. 7.6 min, p = 0.026), and fluoroscopy dose (208.4 mGy vs. 332.3 mGy, p = 0.024)] than patients using TF. Other perioperative efficacy outcomes (PVI success, free from AF after RFCA and complications) showed no difference between the matched pairs. ICE can enhance procedural safety and efficiency of RFCA, particularly for more complex patient profiles, in real-world setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common cardiac arrhythmia, and its prevalence is increasing globally1, including in China2. Radio-frequency catheter ablation (RFCA) is a well-established and effective treatment option addressing the medical needs of AF patients who fail to control the arrhythmia through medications or are intolerant to medications3. Many cardiac imaging technologies have been developed to improve the performance and clinical outcomes of RFCA over the last two decades. One of these technologies is intracardiac echocardiography (ICE). It has been used in the field of electrophysiology since the early 1990s4 and can provide real-time visualization of cardiac structures and catheter positioning to optimize the ablation process. Numerous research studies and clinical trials were conducted to assess the efficacy and safety of ICE in the context of RFCA from the late 1990s to the early 2000s. These studies reported that using ICE to guide RFCA can enhance procedural outcomes, reduce complications, and improve patient safety5.

According to the recently published Chinese expert consensus on the applications of ICE6, ICE is strongly recommended to guide RFCA for AF because of the advances of ICE in imaging the interatrial septum, identifying the location and anatomy of the fossa ovalis, and locating an ideal transseptal puncture site. In addition, ICE could be more attractive than transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) in screening left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with AF as it is associated with an absence of discomfort, greater compliance, and a lower incidence of complications7,8,9. In addition, ICE could guide RFCA for AF with substantially reduced radiation exposure or even completely avoiding radiation exposure under the support of a 3D electroanatomic mapping system10,11,12,13. In addition, ICE can be used to guide other cardiovascular interventions, including cryoablation, transcatheter valve procedures, left atrial appendage occlusion, structural heart repairs, and ventricular assist device placements, providing real-time imaging for improved precision and safety14,15,16,17,18. To generate evidence for the clinical values of using ICE to guide RFCA and support the recommendations on ICE from the Chinese expert consensus6, we conducted this real-world study to compare ICE-guided RFCA with traditional fluoroscopy (TF)-guided RFCA for clinical performance and perioperative outcomes in Chinese patients with AF.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study consecutively enrolled AF patients undergoing RFCA in West China Hospital from March 2022 to July 2023. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the West China Hospital Ethics Review Committee (Application number: 2022 − 323). The informed consent to participate was waived by the West China Hospital Ethics Review Committee because of the retrospective nature of this study. This study was conducted under the guidance of The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement19. The methods for creating the study cohort, data collection, and data analyses are detailed below.

Study cohort

Hospital admission and discharge records were scrutinized to identify patients undergoing RFCA for AF during the study observation period. The study included adult patients (aged 18 years or above) diagnosed with paroxysmal or persistent AF undergoing their first RFCA with ThermoCool SmartTouch Catheter (ST) or ThermoCool SmartTouch Surroundflow Catheter (STSF) during the study period and guided by either ICE or TF. The protocols for ICE-guided and TF-guided RFCA share common steps, including patient preparation, vascular access, transseptal puncture, ablation, and post-procedure assessment. However, ICE-guided RFCA uses an ICE catheter for real-time visualization of cardiac structures, enabling precise transseptal puncture, dynamic monitoring of catheter contact and lesion formation, and significantly reducing fluoroscopy and radiation exposure. In contrast, TF-guided RFCA relies on fluoroscopic imaging and contrast injection to navigate catheters, locate anatomical landmarks, and guide ablation. The study excluded patients aged 80 years or above and patients with cardiovascular events (acute myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft, and/or heart valve surgery) within three months before RFCA.

Study data

Patients meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were linked to RFCA hospitalization records to identify and extract study data. Demographic information, socioeconomic status, disease details (AF type, previous antiarrhythmic treatment), heart function [the New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification]20, stroke risk assessment [(Congestive heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction, Hypertension, Age ≥ 75 (doubled), Diabetes, Stroke (doubled)-Vascular disease, Age 65–74, Sex category (CHA2DS2-VASc) score]21, bleeding risk assessment [Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly, Drugs/alcohol concomitantly (HAS-BLED) score]22, and comorbidities were extracted from hospital admission records. Imaging results, including left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left atrium, and left ventricle diameters, were obtained from echocardiogram. Surgical notes of RFCA provided details on the utilization of ICE or TF for the guidance of RFCA, the interventional cardiologist conducting RFCA procedure, ablation catheter type, quantitative ablation software parameters, VISITAG™ model parameters, ablation sites, procedural outcomes (first transseptal puncture success, PVI conducting time, catheter irrigation volume), radiation exposure (utilization of radiological contrast agent, fluoroscopy time, and fluoroscopy dose), ablation outcomes [PVI success (successful achievement of electrical isolation of all targeted pulmonary veins, demonstrated by the absence of electrical conduction from the pulmonary veins to the left atrium) and free of AF after RFCA (absence of AF episodes > 30 s duration, detected via continuous monitoring before discharge)], and complications related to RFCA including, but not limited to, hematoma, pericardial effusion, perforation, thromboembolism, and infection. This study didn’t follow up patients after their hospital discharges. Thus, the follow-up time in this study was set from the beginning of RFCA to hospital discharge after RFCA.

Statistical data analysis

The enrolled patients were classified into two study groups by the method used to guide RFCA (ICE-guided group vs. TF-guided group) to conduct the following analysis. The data collected from the two study groups were summarized using descriptive statistical methods, which were selected according to the type and distribution of the collected data. The two study groups were further compared using parameter tests (Student’s t-test for continuous data following normal distribution and chi-square test for categorical data and the distributions of categorical levels) and non-parameter tests (Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous data with skewed distribution). Patient characteristics with significant differences between the two study groups were studied in using a multiple logistic regression analysis to explore the factors influencing the selection of ICE to guide RFCA.

This study conducted propensity score-matched (PSM) analysis in patients who underwent RFCA for PVI only to minimize the confounding effects in the comparisons of procedural outcomes, ablation outcomes, and complications related to RFCA between ICE-guided RFCA and TF-guided RFCA. To optimize the number of matched pairs, the matching was conducted until the patient characteristics of the matched pairs were balanced without significant differences. The comparisons of continuous outcomes between the propensity score-matched pairs, including ablation time, total surgery time, utilization of radiological contrast agent, and fluoroscopy time, were conducted using paired t-test. McNemar’s test was used to compare the categorical outcomes, including first transseptal puncture success, PVI success, free of AF after RFCA, and reported complications related to RFCA, between the propensity score-matched pairs.

All data analyses were conducted using statistical software R (v4.1.2). Statistical significance in these data analyses was defined as a two-sided p-value less than 0.05.

Results

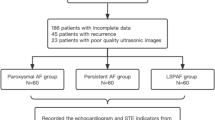

A total of 227 AF patients were included in this study after excluding 15 patients aged 80 years or more (n = 6), who had cardiovascular events within 3 months before RFCA (n = 4), or who underwent a previous treatment with RFCA (n = 2). The 227 included patients were examined to describe the utilization of ICE and explore the patient characteristics and procedural characteristics influencing the selection of ICE to guide RFCA. Among the cohort of 227 patients, 156 undergoing RFCA for PVI only were studied separately to compare ICE-guided RFCA and TF-guided RFCA for procedural outcomes, radiation exposure, ablation outcomes, and RFCA-related complications. The patient identification flowchart is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Differences in patient characteristics and procedural characteristics between ICE-guided RFCA and TF-guided RFCA

Of the 227 patients, 76 patients (33.5%) underwent ICE-guided RFCA to treat their AF. The two study groups (ICE vs. TF) were highly comparable in socioeconomic status, distribution of AF type, and previous antiarrhythmic treatment. For other patient characteristics, the two groups were significantly different in age (65.0 years vs. 60.3 years, p = 0.001), proportions of atrial tachycardia (10.5% vs. 2.6%, p = 0.029) and heart failure (17.1% vs. 7.9%, p = 0.038), diameter of the left atrium (42.5 mm vs. 39.8 mm, p = 0.011), CHA2DS2-VASc score (2.2 vs. 1.6, p = 0.002), and HAS-BLED score (1.7 vs. 1.2, p < 0.001). The baseline patient characteristics of the two study groups are summarized in Table 1.

The comparisons of procedural characteristics between the two study groups displayed significant differences in the distributions of surgeons, ablation approaches, type of ablation catheter, and VISITAG™ model parameters (Table 2). The included patients were primarily operated on by three interventional cardiologists who were highly experienced in conducting RFCA but had varying experience in conducting ICE-guided RFCA. It is evident that the interventional cardiologist (FH) conducting the highest volume of ICE-guided RFCA (10 cases per month) had a greater representation in the ICE group (50.0% vs. 22.5%, p < 0.001). Conversely, the interventional cardiologist (ZR) conducting the least volume of ICE-guided RFCA (3 per month) predominantly utilized TF to guide RFCA and had the lowest representation in the ICE group (3.9% vs. 31.8%, p < 0.001). In addition, the two study groups were not balanced in the proportions of ablation site (PVI plus Floor line: 13.2% vs. 4.0%, p = 0.011) and the catheter used for ablation [Smart-Touch® (ST) catheter: 90.8% vs. 67.5%, p < 0.001; Smart-Touch® Surroundflow (STSF) catheter: 9.2% vs. 32.5%, p < 0.001). Finally, the set temperature in the VISITAG™ model for the ICE-guided RFCA group was significantly higher than that for the TF-guided RFCA group (32.1 ℃ vs. 30.1 ℃, p = 0.001).

Factors influencing the selection of ICE-guided RFCA in the included AF patients

Of the collected patient characteristics and procedural characteristics, age, concurrence with atrial tachycardia, CHA2DS2-VASc score, HAS-BLED score, left atrial diameter, comorbidity with heart failure, interventional cardiologist, and PVI plus floor line ablation (bottom region ablation of the pulmonary vein ostium) were significantly associated with the selection of ICE-guided RFCA in simple logistic regression analyses. The multiple logistic regression analysis of these covariates found that concurrence with atrial tachycardia [odds ratio (OR) 3.692, p = 0.062], HAS-BLED score (OR 1.541, p = 0.050), comorbidity with heart failure (OR 2.098, p = 0.156), and having one interventional cardiologist (FH) (OR 1.876, p = 0.070) were associated with a strong but non-statistical trend of more patients’ receiving ICE-guided RFCA in the included patients. One interventional cardiologist (ZR) was associated with conducting significantly fewer cases of ICE-guided RFCA (OR 0.147, p = 0.003). The results of this multiple logistic regression analysis are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Differences in the measured outcomes of ICE-guided RFCA and TF-guided RFCA for PVI only

Of the 227 included patients in this study, 156 patients (68.7%) undergoing RFCA for PVI only (ICE-guided RFCA: 50 patients; TF-guided RFCA: 106 patients) were separately examined to conduct propensity score matching. The patient characteristics and procedural characteristics of the two study groups were compared to identify the criteria that were used to calculate the propensity score. The two groups were matched on age, CHA2DS2-VASc score, HAS-BLED score, left atrial diameter, concurrent atrial tachycardia, comorbidity with heart failure, ablation temperature used in the VISITAG™ model, and ablation catheter type. A total of 47 pairs were matched using these criteria, and the patient characteristics and procedural characteristics of these 47 patient pairs were well balanced. The comparisons of the measured outcomes for these 47 matched patient pairs found that ICE-guided RFCA was associated with a significantly higher first transseptal puncture success rate (100% vs. 87.2%, p = 0.041) and significantly less radiation exposure (utilization of radiological contrast agent: 2.7 ml vs. 6.0 ml, p < 0.001; fluoroscopy time: 5.7 min vs. 7.6 min, p = 0.026; radiation exposure dose: 208.4 mGy vs. 332.3 mGy, p = 0.024). The matched patient pairs were comparable in the PVI conducting time, catheter irrigation time, ablation outcomes for PVI success, and free from AF after RFCA, and RFCA-related complications (one reported pericardial effusion and one reported hematoma at the site of inguinal puncture). The comparisons of the measured outcomes in the propensity score-matched 47 patient pairs are summarized in Table 3.

Discussion

This study delves into the practical application of ICE in guiding RFCA procedures for AF within a Chinese tertiary care hospital. The findings of this study highlight the advantages of ICE-guided RFCA over TF-guided RFCA, particularly in reducing radiation exposure and improving the first transseptal puncture success rate during PVI procedures. Patient and procedural characteristics, including older age, higher CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores, larger left atrial diameters, and the presence of atrial tachycardia or heart failure, were associated with increased utilization of ICE-guided RFCA. Despite these differences, both guidance methods achieved comparable outcomes in terms of PVI success, long-term freedom from AF, and RFCA-related complications. These findings underscore the potential for ICE to enhance procedural safety and efficiency, particularly for more complex patient profiles.

It is noteworthy that ICE was selected to guide RFCA in only about one-third of the cases, despite the strong support for ICE which has the capacity to fully replace TEE23. The distinctions in patient characteristics between the ICE-guided RFCA and TF-guided RFCA groups, such as older age and associated comorbidities, may account for this variance in utilization. The real-time visualization capabilities of ICE, offering insights into cardiac structures and catheters within heart chambers, play a pivotal role in enhancing procedural precision for tasks like transseptal puncture, mapping, and ablation during RFCA24. This unique capability elucidates the increased use of ICE in patients with larger left atria, indicative of higher thromboembolic risk, procedural challenges, and elevated complication risks25.

Beyond patient characteristics, the experience of the interventional cardiologist conducting the ICE-guided RFCA emerges as a key factor influencing technology adoption. Interventional cardiologists with more substantial experience in ICE-guided procedures exhibit a stronger preference for this technology, underlining the potential barrier of limited experience in hindering ICE adoption. While the ICE technology has garnered validation for treating AF in Western countries, the lack of real-world studies of large patient cohorts has hindered the comprehensive assessment of its clinical values in diverse settings. Notably, a survey study highlighted that the interventional cardiologists with personal experience in ICE-guided RFCA demonstrated a better understanding of the clinical benefits of ICE, expressed higher satisfaction with its operational convenience, and displayed a greater inclination to incorporate ICE technology into RFCA procedures26. This emphasizes the importance of an ICE technology training program and financial support in facilitating adoption. Finally, the cost of ICE could be another barrier to its adoption in China, as Chinese patients are unlikely to use expensive medical devices that are not covered by medical insurance.

The study employed propensity score matching analysis for patients undergoing PVI only, aiming to control potential confounding effects resulting from complicated AF. Results confirmed the superiority of ICE-guided RFCA over traditional fluoroscopy-guided RFCA for first-time atrial septal puncture success and reduced radiation exposure. However, certain previously reported clinical benefits of ICE-guided RFCA, such as improved procedural safety, better ablation outcomes, and shorter procedure times, were not evident in our real-world setting. It is noteworthy that the performance of RFCA procedures by experienced cardiologists in this study may not showcase the same obvious advantages of ICE technology as their less-experienced counterparts. This difference could be attributed to the fact that experienced practitioners have a high level of proficiency in RFCA procedures that could discount the improvements from ICE27. This potentially explains the differences observed in first-time atrial septal puncture success rate and radiation exposure outcomes, which are less pronounced compared to earlier observational studies28,29. In recent years, some studies have explored the potential of ICE as a real-time imaging modality to monitor lesion formation during PVI and indicated that ICE could improve the durability of lesion sets by offering real-time guidance30. Because our study didn’t follow up patients for the recurrence of AF after hospital discharge, further studies are needed to validate ICE’s utility in this context and to standardize its application during PVI procedures.

This study has major limitations and requires cautions to avoid overgeneralizing the findings. Conducted in a single tertiary care hospital with a limited sample size, the study focused on patients undergoing ICE-guided RFCA who were likely selected due to their complex disease profiles. RFCA procedures conducted by only highly experienced interventional cardiologists in this study could introduce selection bias and confounding effects31, limiting the ability of the study to fully uncover the anticipated advantages of ICE-guided RFCA in terms of fewer perioperative complications, which include perforation of cardiac structures, hepatoma formation, pericardial effusion, and tamponade. In addition, the small sample size of this study may not have provided sufficient statistical power to detect the potential advantages of ICE. Therefore, future research with a larger sample size and adequate follow-up is needed to further investigate and confirm the clinical benefits of ICE-guided RFCA in patients with AF.

In summary, this study underscores the preference for using ICE-guided RFCA in patients with complicated AF in a real-world setting and highlights the transformative role of ICE in RFCA procedures for AF through the improved first-time atrial septal puncture success rate and reduced radiation exposure in patients undergoing ICE-guided RFCA. While acknowledging the need for caution in interpreting the findings due to inherent limitations, the study calls for future real-world investigations to evaluate the advantages of ICE technology, particularly when employed by young interventional cardiologists.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to data ownership and agreements. The access to the research data of this study can be requested through the corresponding author of this manuscript under the guidance of research data management in West China Hospital.

References

Lippi, G., Sanchis-Gomar, F. & Cervellin, G. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: an increasing epidemic and public health challenge. Int. J. Stroke. 16, 217–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493019897870 (2021).

Sun, T. et al. Prevalence and trend of atrial fibrillation and its associated risk factors among the population from nationwide health check-up centers in China, 2012–2017. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1151575. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1151575 (2023).

Joglar, J. A. & Peer Review Committee Members. ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 149, e1-e156, DOI: (2023). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193 (2024).

Jongbloed, M. R. et al. Clinical applications of intracardiac echocardiography in interventional procedures. Heart 91, 981–990. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2004.050443 (2005).

Goya, M. et al. The use of intracardiac echocardiography catheters in endocardial ablation of cardiac arrhythmia: meta-analysis of efficiency, effectiveness, and safety outcomes. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 31, 664–673. https://doi.org/10.1111/jce.14367 (2020).

Zhong, J. et al. Intracardiac echocardiography Chinese expert consensus. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 1012731. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.1012731 (2022).

Anter, E. et al. Comparison of intracardiac echocardiography and transesophageal echocardiography for imaging of the right and left atrial appendages. Heart Rhythm. 11, 1890–1897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.07.015 (2014).

Patel, K. M. et al. Complications of transesophageal echocardiography: a review of injuries, risk factors, and management. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc Anesth. 36, 3292–3302. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2022.02.015 (2022).

Zeng, R. et al. Oropharynx pain, discomfort, and economic impact of transesophageal echocardiography for planned radio-frequency catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation: a cross-sectional survey study. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 48, 101266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcha.2023.101266 (2023).

Haegeli, L. M. et al. Feasibility of zero or near zero fluoroscopy during catheter ablation procedures. Cardiol. J. 26, 226–232. https://doi.org/10.5603/CJ.a2018.0029 (2019).

Rajendra, A. et al. Steerable sheath visualizable under 3D electroanatomical mapping facilitates paroxysmal atrial fibrillation ablation with minimal fluoroscopy. J. Interv Card Electrophysiol. 66 (2), 381–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-022-01332-8 (2023).

Troisi, F. et al. Zero Fluoroscopy Arrhythmias Catheter Ablation: A Trend Toward More Frequent Practice in a High-Volume Center. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 804424. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.804424 (2022).

Tahin, T. et al. Implementation of a zero fluoroscopic workflow using a simplified intracardiac echocardiography guided method for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation, including repeat procedures. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 21 (1), 407. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02219-8 (2021).

Enriquez, A. et al. Fluoroless catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a step-by-step workflow. J. Interv Card Electrophysiol. 66 (5), 1291–1301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-023-01469-0 (2023).

Catanzariti, D. et al. Usefulness of Contrast Intracardiac Echocardiography in Performing Pulmonary Vein Balloon Occlusion during Cryo-ablation for Atrial Fibrillation. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol. J. 12 (6), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0972-6292(16)30563-0 (2012).

Rubesch-Kütemeyer, V. et al. Reduction of radiation exposure in cryoballoon ablation procedures: a single-centre study applying intracardiac echocardiography and other radioprotective measures. Europace 19 (6), 947–953. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euw139 (2017).

Cuellar-Silva, J. R. et al. Rhythmia zero-fluoroscopy workflow with high-power, short-duration ablation: retrospective analysis of procedural data. J. Interv Card Electrophysiol. 65 (2), 499–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-022-01283-0 (2022).

Skeete, J. et al. Prospective study of zero-fluoroscopy laser balloon pulmonary vein isolation for the management of atrial fibrillation. J. Interv Card Electrophysiol. 66 (7), 1669–1677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-023-01477-0 (2023).

von Elm, E. et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 147 (8), 573–577. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 (2007).

Dolgin, M. et al. Nomenclature And Criteria For Diagnosis Of Diseases Of The Heart And Great Vessels 9th edn (Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1994).

Lip, G. Y. et al. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach. Chest 137, 263–327. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-1584 (2012).

Skanes, A. C. et al. Focused 2012 update of the Canadian cardiovascular society atrial fibrillation guidelines: recommendations for stroke prevention and rate/rhythm control. Can. J. Cardiol. 28, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2012.01.021 (2012).

Alkhouli, M., Hijazi, Z. M., Holmes, D. R., Rihal, C. S. & Wiegers, S. E. Intracardiac echocardiography in structural heart disease interventions. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 11, 2133–2147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2018.06.056 (2018).

Perk, G. et al. Use of real time three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography in intracardiac catheter based interventions. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 22, 865–882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2009.04.031 (2009).

Den Uijl, D. W. et al. Impact of left atrial fibrosis and left atrial size on the outcome of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Heart 97, 1847–1851. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2011.224279 (2011).

Pu, X. et al. Intracardiac echocardiography operational experience of Chinese interventional cardiologists in conducting radio-frequency catheter ablation for cardiac arrhythmias: a cross-sectional survey study. Value Health. 26 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2023.09.2232 (2023).

Chang, F. C. et al. Surgical volume and outcomes of surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation: a nationwide population-based cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23 (1), 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03101-5 (2023).

Capulzini, L. et al. Feasibility, safety, and outcome of a challenging transseptal puncture facilitated by radiofrequency energy delivery: a prospective single-centre study. Europace 12, 662–667. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euq019 (2010).

Liang, K. W. et al. Intra-cardiac echocardiography guided trans-septal puncture in patients with dilated left atrium undergoing percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy. Int. J. Cardiol. 117 (3), 418–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.05.059 (2007).

Sze, E. et al. Pulmonary Vein Isolation Lesion Set Assessment During Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation. J. Innov. Card Rhythm Manag. 8 (2), 2602–2611. https://doi.org/10.19102/icrm.2017.080204 (2017).

Huang, S. et al. Characteristics of diagnosis and treatment of tamponade of catheter ablation for arrhythmias. J. Clin. Pathol. Res. 36, 427–432. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2095-6959.2016.04.016 (2016).

Funding

This study was funded by Johnson and Johnson Medical (Shanghai) Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.F., R.Z., Y.T., X.P., and W.C. were responsible for study conception, planning and design. Y.T., X.P., S.C., A.G., and Y.C. conducted data collection. C.C. and Y.C. conducted data cleaning and analysis. All authors participated in data interpretation, drafting the manuscript (and/or making substantive intellectual contributions), reviewing the final version and agreeing to be accountable for the study and its findings.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Chunjia Chen, Yi Chen, and Wendong Chen are employed by contract research organizations that receive industry funds to conduct health economics and outcomes research. Yao Tong, Xiaobo Pu, Shi Chen, Aobo Gong, Ying Cao, Hua Fu, and Rui Zeng declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tong, Y., Pu, X., Chen, S. et al. Real-world evaluation of intracardiac echocardiography guided radio-frequency catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 14, 31521 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83186-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83186-w