Abstract

Cinnamomum camphora, a key multifunctional tree species, primarily serves in landscaping. Leaf color is crucial for its ornamental appeal, undergoing a transformation to red that enhances the ornamental value of C. camphora. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying this transformation remain largely unexplored. In this study, green leaf (GL), color turning red leaf (RL) and whole red leaf (WRL) were obtained to measure pigment contents, while GL and RL were analyzed for transcriptomic alterations. A decline in chlorophyll content and a rise in anthocyanins were observed during the transition from green to red leaves. Using LC MS/MS, 11 types of anthocyanins showed significant accumulative differences, with cyanidin-3,5-O-diglucoside exhibiting the greatest disparity. Comparative RNA-seq identified 22,948 genes against reference genes, revealing 544 novel genes. Of these, 3,222 genes were up-regulated and 7,391 genes were down-regulated when the FPKM mean value > 1 in at least one group. The ribosome was identified as the most abundant KEGG term, with a substantial number of down-regulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs). The results indicated a downward trend in protein content, with GL exhibiting the highest protein concentration. 22, 4, and 29 DEGs were associated with chlorophyll biosynthesis, chlorophyll degradation, and anthocyanin biosynthesis, respectively. Most DEGs related to chlorophyll biosynthesis were down-regulated. SGR and SGRL, which are associated with chlorophyll degradation, exhibited opposite differential expression, resulting in a significant decrease in chlorophyll content in RL. The significantly up-regulated genes ANS and UFGT are advantageous for anthocyanin biosynthesis, contributing to the red coloration observed. Additionally, differential expression was noted in 40 R2R3-MYBs. Two MYB90 (Ccam01G003512 and Ccam01G003515) homologs of AtMYB113 were also identified showed high levels of up-regulation in RL. These findings suggest a strong correlation between pigment metabolism and transcriptome data, elucidating the mechanism that leads to the red coloration of leaves in C. camphora.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leaf color, as vital as flower and fruit color, is a primary characteristic of ornamental plants that captures attention. Unlike flowers and fruits, which appear only briefly, leaf colors constitute a prominent feature that contributes to the unique landscapes within the plant kingdom1. In deciduous species, leaf colors change with plant development or seasonal shifts, such as the red leaves of the Norway maple in autumn2. However, the camphor tree (Cinnamomum camphora), a prevalent evergreen and landscape tree, is also an economically and ecologically significant aromatic species widely distributed in China. It is particularly noted for its leaves, which may turn red in any season, thereby enhancing the ornamental value of C. camphora.

Plant pigments impart rich colors to various organs. Studies suggest that changes in leaf color are closely linked to the synthesis and accumulation of these pigments3,4,5. Plant coloration primarily depends on the types and concentrations of three key pigments: chlorophylls, anthocyanins, and carotenoids. Chlorophylls are the main components of normal green leaves. However, the loss of green color often results from disruptions in the chlorophyll biosynthesis pathway, which exposes other colorful pigments6. Carotenoids, synthesized exclusively in plants, encompass more than 700 members and contribute yellow, orange and red hues7. They also synthesize other substances and provide protection to plants8. Anthocyanins, which are water-soluble polyphenols within the flavonoid group, number over 600 and are predominantly responsible for the red colors in ornamental plant tissues9.

The biosynthesis pathway of anthocyanins has been extensively studied in ornamental plants, such as Prunus persica10, Bauhinia variegata11, and Prunus mume12. Numerous studies have highlighted the roles of structural genes and transcription factors (TFs) in these plants13. Anthocyanin synthesis is catalyzed by several enzymes, including chalcone synthase (CHS), dihydroflavonol reductase (DFR), flavanone-3-hydroxylase (F3H), anthocyanidin synthase/leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase (ANS/LDOX), and UDP glucose flavonoid 3-glucosyltransferase (UFGT). Glycosylated anthocyanins are transported to vacuoles by specialized transporters, such as glutathione S-transferase (GST), ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE), and multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP)14,15, which protect them from the cytoplasmic environment. Structural genes are typically regulated by TFs (e.g. bHLH, MYB and WD40)16. MYB can function independently or in ternary complexes with two other TFs (known as MBW). In poplar, the over-expression of PdMYB118 leads to the up-regulation of most structural genes and an increase in anthocyanins production in the leaves17. Recent studies indicate the involvement of other TF families, including MADS, WRKY and bZIP, in anthocyanin synthesis18,19,20.

With the advent of next-generation sequencing, transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) has emerged as a powerful tool for identifying candidate genes involved in various biological processes. The camphor tree is diploid (2n = 24) and possesses 12 chromosomes. Its genome sequencing has been completed21, and RNA-Seq has identified 2,017 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) related to the red bark mutant (‘Gantong 1’), including 24 up-regulated DEGs implicated in anthocyanin biosynthesis and 6 TFs22. Luan et al. identified 121 CcMYBs distributed across the 12 chromosomes of C. camphora, and RNA-Seq data from seven tissues suggest that CcMYBs from three subgroups may play a role in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway23. Certain species of Pistacia chinensis exhibit anthocyanin accumulation in their leaves, which turn red in autumn. Transcriptomic data have demonstrated that 31 structural genes in the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway are up-regulated, with MYB113 expression correlating with anthocyanin content under both natural and shaded conditions24.

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the color changes in C. camphora leaves. To achieve this, we carried out pigment concentration analysis and gene expression profiling using RNA-Seq to identify the primary pigment types and key genes involved in the transition of leaf coloration to red. This research provides valuable insights into the mechanisms of coloration changes in the C. camphora.

Results

Colorimetric changes during the leaf color transformation

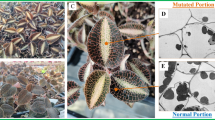

Through consistent observation, we noted that a portion of C. camphora leaves undergoes a color change from green to red, a phenotype observable year-round (Fig. 1A). After counting 492 WRL across 335 branches and recording their locations, we found that all WRL were concentrated in the last five leaves at the ends of the branches, with distributions of 44.72%, 22.97%, 22.97%, 6.91%, and 2.44%, respectively (Fig. 1B). Colorimetric measurements were performed on both the adaxial (Ad) surface (Fig. 1C) and abaxial (Ab) surface (Fig. 1D) of the leaves. On the Ad surface, the L* values showed no significant differences among GL, RL, and WRL. However, the L* values on the Ab surface of WRL were significantly lower than those of GL and RL. For the a* values, both Ad and Ab surfaces exhibited significant differences among GL, RL, and WRL. On both surfaces, GL presented negative a* values, indicating green coloration, while RL and WRL displayed positive a* values, signifying red coloration. Notably, a* values of WRL were higher than those of RL on both surfaces. These results suggest that WRL are redder than RL. Additionally, b* values of WRL were the lowest compared to GL and RL on both surfaces.

Observed color transformation and detected color parameters of C. camphora leaves. (A), the process of leaf color transformation. GL refers to green leaf, RL refers to color turning red leaf, and WRL refers to whole red leaf. (B), the spatial distribution of WRL. Color parameters for the adaxial (C) and abaxial (D) surfaces are shown. Values sharing the same letters are not significantly different, as determined by Duncan’s Multiple Range Tests (P = 0.05).

Major pigments in the red leaves of C. camphora

To identify the main pigments responsible for the transformation of leaf color, the contents of chlorophylls, carotenoids, and anthocyanins were measured. The results indicated that color profiles varied significantly among GL, RL, and WRL. The contents of chlorophyll a (Fig. 2A), chlorophyll b (Fig. 2B), and total chlorophyll (Fig. 2C) exhibited a significant decrease from GL to WRL. When the leaf color had completely turned red, the levels of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll were reduced to only 1.79%, 9.47%, and 3.98% of those in GL, respectively. The carotenoid content was similar between RL and WRL but showed a significant decrease compared to GL (Fig. 2D). In contrast to GL and RL, WRL exhibited the highest anthocyanin content, reaching up to 532.13 µg·g− 1 (Fig. 2E). Using LC MS/MS, 27 anthocyanins were detected in both GL and WRL. Among these, 11 anthocyanins were identified as differentially accumulated metabolites, including three cyanidins (cyanidin-3,5-O-diglucoside, cyanidin 3-O-sophoroside and cyanidin 3-O-xyloside), one peonidin (peonidin 3-O-galactoside), one pelargonidin (pelargonidin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside), three delphinidins [delphinidin 3-O-sophoroside, delphinidin 3-(6-rhamnosylgalactoside) and delphinidin 3-rutinoside-5-glucoside] and three other anthocyanidins (aurantinidin, 6-hydroxycyanidin and 5-carboxypyranocyanidin 3-O-β-glucopyranoside) (Fig. 2F). WRL accumulated more anthocyanins than GL contributing to the red coloration. Among these, cyanidin-3,5-O-diglucoside, peonidin 3-O-galactoside, and pelargonidin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside exhibited the most significant differences.

RNA library construction and sequencing

To characterize the differences in gene expression levels between GL and RL, six cDNA libraries were constructed, comprising three from GL (designated GL1, GL2, and GL3) and three from RL (designated RL1, RL2, and RL3). It is noteworthy that RNA from WRL was degraded, which precluded the construction of cDNA library. A total of 299,566,040 reads (44,934,906,000 bp) were generated as raw data. After filtering out low-quality reads, 297,256,232 reads (44,163,916,131 bp) remained. On average, 92.14% of the reads were mapped to the camphor tree reference genome (Supplementary Table S1). In total, 22,948 genes were sequenced in comparison to the reference genes, and 544 new genes were identified (Supplementary Table S2). Among these new genes, 231 were unnamed, 212 were classified under Cinnamomum micranthum f. kanehirae, and the remaining 101 were distributed across 63 plant species.

The contrastive analysis of transcriptome data between GL and RL

The transformation of leaf color is a complex process characterized by significant transcriptome variation between GL and RL, as evidenced by a substantial number of DEGs. In total, 12,217 DEGs were identified (Supplementary Table S3), including 4,065 up-regulated genes and 8,152 down-regulated genes (Fig. 3A). After applying a filter of FPKM (fragment per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) mean > 1 in at least one group, 3,222 up-regulated and 7,391 down-regulated genes remained (Fig. 3A). From these, we selected 30 DEGs with the greatest fold change (fc) differences in gene expression (Supplementary Table S4). Among these, 24 were down-regulated, and 5 were identified as novel genes (Fig. 3B). Ccam02G002785 exhibited the highest positive log2 (fc) value of 14.928, while Ccam01G002624 showed the highest negative value at -16.493. The 12 DEGs have symbols are not specified (-), while others are At3g13620 (putative polyamine transporter), At5g02620 (ankyrin repeat), At1g75720 (WEB family protein), At3g21340 (protein kinase domain-containing protein), At1g06270 (pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein At1g06270), Os06g0561000 (putative inositol oxygenase), ATJ11 (chaperone protein dnaJ 11, chloroplastic), RPL27 (60 S ribosomal protein L27), CYP76T24 (cytochrome P450), TAX1 (hypothetical protein CKAN_01539100), OFP3 (ovate protein family), PER17 (peroxidase 17-like protein), HST (spermidine hydroxycinnamoyl transferase), CXXS1 (thioredoxin-like protein CXXS1), PLT2 (polyol transporter 5), LRR-RLK (protein kinase domain-containing protein), DVL14 (small polypeptide DEVIL 14-like), and ML1 (PREDICTED: protein MEI2-like 7). Results from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses indicate that Ccam08G001666 (HST) and Ccam08G000119 (PER17) are involved in the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway, with HST also participating in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway. Ccam04G002717 (RPL27) is associated with ribosome, while Ccam06G000661 (CYP76T24) is related to monoterpenoid biosynthesis. Additionally, Ccam04G001873 (Os06g0561000) is involved in ascorbate and aldarate metabolism as well as inositol phosphate metabolism. To validate the accuracy and reliability of the RNA-seq data, 6 DEGs were randomly selected for confirmation via qRT-PCR. The expression levels of these candidate genes demonstrated a high degree of consistency between RNA-seq and qRT-PCR results (Supplementary Figure S1).

GO and KEGG analysis of the DEGs

To further elucidate the functional roles of DEGs, we conducted Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses. All DEGs were classified into three main categories of GO classification, including biological process (BP), cell components (CC) and molecular functions (MF) (Fig. 4A). For BP, the predominant subcategories were ‘cellular process’ and ‘metabolic process’. For CC, ‘cellular anatomical entity’ and ‘protein-containing complex’ were highly represented. For MF, ‘binding’ and ‘catalytic activity’ were the most represented.

All DEGs underwent KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, resulting in their classification into 137 pathways. Among these, twenty-three pathways exhibited a P-value ≤ 0.05, including ‘ribosome’, ‘pentose phosphate pathway’, ‘porphyrin metabolism’, ‘photosynthesis’, ‘carbon metabolism’, ‘carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms’ and ‘photosynthesis-antenna proteins’. The ‘Ribosome’ (Ko03010) contained the highest number of DEGs, and most of the DEGs were down-regulated in RL. Ribosome was the cellular factory responsible for protein synthesis. Thus, the down-regulation of the majority of DEGs could significantly impact various biological processes. Additionally, the top 30 most enriched pathways were identified (Fig. 4B). The pathways ‘Porphyrin metabolism’ (Ko00860), ‘carotenoid biosynthesis’ (Ko00906) and ‘anthocyanin biosynthesis’ (Ko00942) are associated with the plant pigments chlorophylls, anthocyanins, and carotenoids, respectively.

Ribosome related DEGs between GL and RL

The ribosome is composed of two subunits, which are constructed from RNA and proteins. In cells, ribosome perform the function of translation and play a vital role in cell division, growth, and development25. In this study, we found that the ‘ribosome’ was the most abundant KEGG term, with a total of 247 DEGs belonging to this pathway. Three DEGs exhibited FPKM mean values ≤ 1 in both groups. However, upon their removal, only Ccam04G001485 and MSTRG.15,482 were found to be up-regulated. Among the twenty-three DEGs with |log2 (fc)| ≥ 3, which are associated with the small subunit, only PR-S23e (MSTRG.15482) was identified as up-regulated (Fig. 5A). All sixty DEGs associated with the large subunit were down-regulated (Fig. 5B). The majority of genes were down-regulated, which could adversely affect ribosome generation and protein synthesis. Consequently, we measured changes in protein concentration during leaf color transformation. The results indicated a downward trend in protein content, with GL exhibiting the highest protein concentration compared to RL and WRL (Fig. 5C).

The DEGs related to ribosome pathway and protein content detection. (A) The DEGs (|log2 (fc)| ≥ 3) related to the small subunit of the ribosome pathway. (B) The DEGs (|log2 (fc)| ≥ 3) related to the large subunit of the ribosome pathway. (C) The differences in protein content among GL, RL, and WRL. DEGs with FPKM mean > 1 in at least one group.

DEGs related to chlorophyll biosynthesis and degradation

Chlorophyll biosynthesis and degradation are part of ‘porphyrin metabolism’ (Ko00860). Based on the KEGG pathway analysis, a total of 26 DEGs were identified, with a mean FPKM > 1 in at least one group. This included two up-regulated and twenty-four down-regulated DEGs (Fig. 6). Among these, 22 DEGs are associated with chlorophyll biosynthesis, including OVA3 (Ccam05G002255), HEMA1 (Ccam01G002476 and Ccam04G001696), GSA (Ccam01G002922 and Ccam06G000281), HEMB (Ccam11G001295), HEMC (Ccam07G001413), HEME1 (Ccam10G000902), CPX1 (Ccam10G000600), PPOX1 (Ccam10G001810), CHLH (Ccam10G001073), CHLD (Ccam02G001092), CHLI (Ccam04G000078), CHLM (Ccam02G002041), CRD1 (Ccam01G003276), DVR (Ccam02G001588), PORA (Ccam12G000060), CHLG (Ccam03G003207), CAO (Ccam01G000545), NYC1 (Ccam02G002556), NOL (Ccam03G002262), and HCAR (Ccam12G001422). Almost all of these genes were down-regulated, with the exception of NYC1, which was up-regulated in the RL. Additionally, four DEGs related to chlorophyll degradation were identified, including CLH2 (Ccam02G002637), RCCR (Ccam08G000276), SGR (Ccam07G000443), and SGRL (Ccam09G000375). SGR was up-regulated with a mean FPKM value of 2,593 in the RL. These findings suggest a significant decrease in chlorophyll biosynthesis in RL, with gene expression results aligning with the observed chlorophyll concentration.

DEGs related to anthocyanin biosynthesis

The process of anthocyanin production is associated with three pathways, including ‘phenylpropanoid biosynthesis’ (Ko00940), ‘flavonoid biosynthesis’ (Ko00941) and ‘anthocyanin biosynthesis’ (Ko00942). In this study, we identified 31 DEGs related to anthocyanin within these three pathways, of which two DEGs exhibited a mean FPKM value of ≤ 1 in both groups. The remaining 29 DEGs included four PAL, one C4H, six 4CL, four CCoAOMT, five CHS, one CHI, one F3H, two FLS, one DFR, one ANS and three UFGT (Fig. 7). In contrast to the down-regulated expression of most genes in the chlorophyll biosynthesis pathway, 17 DEGs were significantly up-regulated, comprising three PAL, three CCoAOMT, one C4H, three 4CL, three CHS, one FLS, one ANS, and two UFGT. Notably, the up-regulated genes, 4CL (Ccam06G002027, Ccam08G001811, and Ccam03G001045), ANS (Ccam10G000921), and UFGT (Ccam02G000147 and Ccam02G000149) may contribute to increased anthocyanin synthesis in RL.

DEGs related to anthocyanin transport

Some members of the GST, ABC, and MATE families are participate in anthocyanin transport. In this study, we identified 99 DEGs with a mean FPKM > 1 in at least one group, including 26 GST members (Fig. 8A), 21 MATE members (Fig. 8B), and 52 ABC members (Fig. 8C). Most of these DEGs were down-regulated. Among these GST members, Ccam09G000246 was the only gene that was up-regulated with a log2 (fc) of 9.6, and belonging to the GSTF11. The mean FPKM value of Ccam09G000246 was 0.40 in GL, but increased to 311.77 in RL. MATE also known as detoxification efflux carriers (DTXs), and we identified 12 up-regulated and 9 down-regulated DEGs among DTX members. Ccam07G001134 (DTX41) and Ccam09G001225 (DTX40) was homologs of AtTT12, while Ccam08G001106 was a homolog of ATDTX1. Ccam09G000832, Ccam08G000970, and Ccam01G000525 were homologs of ATDTX35. In ABC family, 19 up-regulated and 33 down-regulated DEGs were screened out. These ABC members included ABCA, ABCB, ABCD, ABCF, ABCG, ABCI, and STAR1.

TFs analysis

In this study, a total of 1,691 TFs were identified, categorized into 58 families. Among these, 568 DEGs with a mean FPKM > 1 in at least one group belong to 51 distinct TF families (Fig. 9A). The majority of these DEGs are classified as bHLH, ERF, MYB, WRKY, C2H2, and NAC, followed by bZIP, MYB-related, and G2-like. These DEGs of TFs were subjected to BLAST analysis the Arabidopsis TAIR 10 protein database (Supplementary Table S5). TFs can influence pigment biosynthesis by regulating the expression of structural genes. MYB and bHLH are critical TFs involved in flavonoid and anthocyanin biosynthesis. We identified 57 bHLH, 39 MYB, 19 G2-like, and 21 MYB-related genes that exhibited differential expression. Domain analysis revealed thirty-six 1R-MYBs, forty R2R3-MYBs, and two 3R-MYBs, with no 4R-MYBs detected (Supplementary Table S6). Gene expression analysis of R2R3-MYBs indicated that 21 were up-regulated and 19 down-regulated in RL compared to GL (Fig. 9B). Three MYB78 members, homologous to AtMYB78, were up-regulated, while two MYB90 homologs of AtMYB113 were also identified. These MYB members play a regulatory role in the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway. The bHLH of DEGs were identified into seventeen subgroups (Fig. 9C, Supplementary Table S7). VIIa + b and XII were the largest subfamilies, both with 10 members. The smallest subfamilies, IVa, IX, VIIb, each had one member.

Discussion

In plants, leaves serve not only as crucial organs for photosynthesis, transpiration, and gas exchange, but they also represent one of the most significant ornamental traits. C. camphora exhibits a phenotype in which the color of its leaves changes from green to red throughout the year, which enhances its ornamental value. Previous studies suggest that leaf color is predominantly influenced by the concentrations of chlorophylls, carotenoids, and anthocyanins in various plants26,27,28. However, the factors regulating the synthesis and degradation of these pigments are complex. In this study, we observed the reddening process of leaves, measured the types and concentrations of pigments, and identified DEGs in RL compared to GL. This work provides a foundation for future elucidation of the molecular mechanisms underlying leaf color change in C. camphora.

Through the determination of pigment content, we found that GL possesses the highest levels of chlorophylls and carotenoids, while WRL exhibits the highest levels of anthocyanins. The degradation of chlorophylls and the accumulation of anthocyanins contribute to the reddening of leaves. Evolution has favored high chlorophyll content in leaves due to its relationship with photosynthesis, resulting in their green color. The biosynthesis and degradation of chlorophylls play a crucial role in leaf coloration. Flavonoids are synthesized through a branched pathway, resulting in both colorless and colored pigments, including anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins. The majority of anthocyanins belong to the cyanidin, peonidin, pelargonidin, delphinidin, malvidin, and petunidin types29. In C. camphora cv ‘Gantong 1’, the red bark contained a higher concentration of anthocyanin compounds compared to the green bark of normal trees, particularly pelargonidin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside which is primarily responsible for the orange-red coloration22. For Acer pseudosieboldianum leaves, the content of cyanidin-3,5-O-diglucoside showed significant differences between the middle and last stage of autumn, suggesting its major role in the final red coloration30. In Ananas comosus var. bracteatus leaves, the cyanidin-3,5-O-diglucoside content was nearly 95.6% in red samples, significantly higher than in green samples31. Comparisons of two purple heading Chinese cabbages revealed that cyanidin 3,5-O-diglucoside, pelargonidin 3-O-β-d-glucoside, and cyanidin O-syringic acid were directly responsible for the observed color differences32. Our results indicate that cyanidin-3,5-O-diglucoside, peonidin 3-O-galactoside, and pelargonidin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside showed the three most significant differences in anthocyanin content. The huge changes in the concentration of these pigments may directly contribute to the redness of C. camphora leaves.

The rapid development of high-throughput sequencing technologies has significantly advanced research methodologies. RNA-seq serves as a valuable tool for identifying key genes related to specific characteristics in ornamental plants, such as C. camphora22, Prunus persica33, and Acer fabri5. In our study, we identified 26 DEGs involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis and degradation. SGR is one of the most important enzymes in the chlorophyll degradation pathway, and the sgr mutation was originally described by Mendel34. Notably, SGR expression is up-regulated during natural and dark-induced leaf senescence35. The mutation in SGR results in the retention of green leaves during senescence by affecting chlorophyll degradation. In rice, SGRL is primarily expressed in green tissues and is significantly down-regulated in leaves undergoing natural and dark-induced senescence36. The expression pattern of SGRL is inversely related to that of SGR1 in Arabidopsis34, which aligns with our RNA-seq results. In our study, SGR and SGRL exhibited opposite differential expression, which caused the chlorophyll biosynthesis was significantly decreased in RL.

Flavonoid biosynthesis is regulated by multiple structural genes. 4CL serves as a crucial rate-limiting enzyme in flavonoid metabolism, directly participating in phenylpropanoid metabolism and subsequently synthesizing flavonoids37. qRT-PCR analysis demonstrated that the expression levels of all 4CL members were directly proportional to the degree of fruit coloration and anthocyanin accumulation38. ANS catalyzes the conversion of colorless proanthocyanidins into colored anthocyanin precursors. Comparative leaf transcriptome analysis of 11 Brassica species with purple or green leaves revealed that ANS was significantly up-regulated in all purple leaves39. UFGT is another key enzyme that stabilizes unstable anthocyanidins. Transcriptomic comparisons of foliar senescence between Prunus cerasifera showed that UFGT was exclusively up-regulated in red leaves compared to green leaves40. In a comparison of the transcriptome data from Chokecherry green, purple, and purplish-red leaves, two UFGT genes (Cluster-24837.111509 and Cluster-24837.123865) exhibited high expression levels as the leaf color transitioned to purple-red41. Additionally, in Cymbidium sinense, qRT-PCR results indicated that ANS expression in the red leaf stage was 833 times higher than in the green leaf stage, while UFGT expression in the red leaf stage was 14 times higher than in the green leaf stage42. Our RNA-Seq analysis identified 29 DEGs related to anthocyanin biosynthesis, including PAL, C4H, 4CL, CCoAOMT, CHS, CHI, F3H, FLS, DFR, ANS, and UFGT. The up-regulation of 4CL, ANS, and UFGT may contribute to increased anthocyanin synthesis in RL.

Anthocyanins are synthesized in the cytosol and subsequently transported to the vacuole, where they display vibrant colors. The coloration of plants is influenced by the transport mechanisms associated with anthocyanin-related genes. Based on amino acid sequences, GSTs can be categorized into various subclasses, which are believed to perform distinct functional roles. Notably, members of the GSTF subclass are primarily responsible for anthocyanin accumulation43. In castor, it is suggested that members of the GSTF subclass play a crucial role in the accumulation of anthocyanin, and it is speculated that their gene function is related to anthocyanin biosynthesis and metabolism44. In our study, we identified an up-regulated DEGs belonging to GSTF11, with a log2 (fc) of 9.6. In Arabidopsis thaliana, the tt12 mutant encoding a membrane protein of the MATE transporter, suggested TT12 involved in the vacuolar accumulation of proanthocyanidin precursors in the seed. In our study, Ccam09G001225 was a homolog of AtTT12 and up-regulated in RL.

TFs are type of proteins that regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis by binding to specific DNA sequences in various plants. It can recognize and bind to cis-acting elements in the upstream regulatory regions of genes through specific functional domains, thereby activating or inhibiting gene expression. In our study, we identified 568 DEGs with a mean FPKM > 1 in at least one group belong to 51 distinct TF families, including bHLH and MYB. MYB is a large TFs superfamily with highly conserved DNA-binding domain repeats and can be divided into four sub-families on the basis of their repeats number. The structural genes encoding these enzymes is tuned by MYB or a conserved MYB-bHLH-WDR (MBW) complex. Over-expression of PsMYB114L and PsMYB12L exhibited significantly accumulated more anthocyanins in transgenic Arabidopsis plants, resulting in purple-red leaves45. In Populus deltoids, PdMYB118 functions have been verified as an essential transcription factor regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis17. In C. camphora, 121 CcMYBs were identified on 12 chromosomes, part of CcMYBs were significantly associated with structural genes involved in flavonoid synthesis. R2R3-MYB members are critical for anthocyanin structural genes46. In our results, we identified 40 R2R3-MYBs belonging to DEGs. In jaboticaba peel, a McMYB homolog of AtMYB113, induced anthocyanin accumulation in tobacco leaves47. In this study, two MYB90 homologs of AtMYB113 were also identified, Ccam01G003512 with log2 (fc) of 10.11 and Ccam01G003515 showed log2 (fc) of 5.93 up-regulated in RL. The L-myc was the first reported bHLH protein in plants, which regulates the flavonoid/anthocyanin biosynthesis. The Arabidopsis bHLH genes belonging to the IIIf subfamily, have been detected to be engaged in the flavonoid biosynthesis. In this study, the bHLH among DEGs were identified into seventeen subgroups, but no IIIf subfamily member. It’s worth noting that the Ccam01G000415 is IIIf subfamily showed log2 (fc) of 5.93, but the mean FPKM ≤ 1 in both two groups. Based on results of proteins interaction, FRU, ILR3, PIF3 and TT8 proteins were detected as the significant interacting bHLHs with the MYB, RGA, CRY1 and bZIP proteins, which can regulate stress coping, iron ion homeostasis and anthocyanin biosynthesis during the sesame life cycle48. More researches have shown that other TF families (like MADS, NAC, WRKY) are involved in anthocyanin synthesis. In pears, transcription factor PpWRKY44 induces anthocyanin accumulation by regulating PpMYB10 expression. Over-expressed PpWRKY44 in leaves and fruit peels significantly enhanced the accumulation of anthocyanin49. In our study, the molecular mechanisms underlying the color transformation of C. camphora leaves to red are complex, particularly regarding anthocyanin synthesis and regulation. The significantly up-regulated expression of the anthocyanin synthesis structural genes ANS and UFGT likely contributes to the increased anthocyanin content. These up-regulated genes are presumably regulated by certain TFs, which require further investigation.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The leaves of C. camphora were collected from the campus of Huaiyin Institute of Technology (Huai’an, China). Ten trees were selected to observe and record the color changes of the leaves. Three trees exhibiting uniform growth were chosen to collect green leaves (GL), color turning red leaves (RL), and whole red leaves (WRL) as plant materials. All samples were either used immediately or frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at -80 ℃.

Determination of color indices

The GL, RL and WRL were collected to measure their color parameters. For each color stage, ten leaves were selected, and color parameter measurements were repeated three times for each leaf. A colorimeter (CR8, Shenzhen ThreeNH Technology Co., Ltd., China) was employed to assess the color differences (L*, a*, and b*) among the GL, RL, and WRL. The L* value indicates lightness, with 0 representing black and 100 representing white. The a* value corresponds to red/green chromaticity, where ‘+’ values indicate ‘redness’ and ‘-’ values indicate ‘greenness’. The b* value corresponds to yellow/blue chromaticity, with ‘+’ values indicating ‘yellowness’ and ‘-’ value indicating ‘blueness’. The color of GL served as the control.

Determination of pigment content

The same GL, RL, and WRL samples were utilized for the assessment of anthocyanins, chlorophylls, and carotenoids content. The determination of total anthocyanin content was conducted following the method described by Mei et al.3. Chlorophyll and carotenoid contents were assessed according to the method outlined by Dong et al.50. All pigment contents were measured in three replicates.

Anthocyanins measurement used the LC-MS/MS

Fresh samples of GL and WRL were pulverized using a tissue grinder at 50 Hz for 120 s. Anthocyanins were extracted from 50 mg of leaf powder in 1 mL 60% MeOH (0.1 mol/L HCl, 0.1% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt by mass fraction) and vortexed for 60 s. The extraction was performed for 10 min under ultrasonic conditions at a temperature of 40 ℃ and a power of 60%. The mixture was centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 rpm and 4 ℃. The supernatant was filtered using a 0.22 μm membrane and transferred into a detection bottle for LC-MS detection. The liquid chromatography conditions followed those described by Hong et al.51, while Mass spectrum conditions followed Zhang et al.52.

The raw data collected by LC-MS/MS were initially converted to mzML format by the MSConvert in ProteoWizard software “package” (v3.0.8789)53 and subsequently processed with XCMS54 for feature detection, retention time correction, and alignment. Anthocyanins were identified based on accuracy mass (< 30 ppm) and MS/MS data, which were matched against databases including KNApSAcK (http://metabolomics.jp), HMDB (https://hmdb.ca), LipidMaps (https://lipidmaps.org), PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), and KEGG (https://www.genome.jp). The robust SVRsignal correction (QC-SVRC)55 was applied for data normalization to correct for any systematic bias. After normalization, only ion peaks with relative standard deviations (RSDs) of less than 30% in QC were kept to ensure proper metabolite identification. All pigment contents were measured in three replicates. Anthocyanins with a |Log 2 (fc)| ≥ 2 and p-value < 0.05 were considered differentially accumulated anthocyanins.

RNA extraction, libraries construction and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from the GL and RL samples using the RNAprep Pure Plant Plus Kit (Polysaccharides and Polyphenolics-rich) (DP441; Tiangen Biotechnology, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Each of the GL and RL samples included three biological replicates. RNA quality was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and checked using RNase-free agarose gel electrophoresis. After purification of total RNA with oligo (dT) magnetic beads, enriched mRNA was fragmented into short fragments using fragmentation buffer and reverse transcribed into cDNA utilizing the NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (#7530, NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA). Subsequently, the double-stranded cDNA fragments were purified, end-repaired, A base added, and ligated to the Illumina sequencing adaptors. The ligation reaction was purified using AMPure XP Beads (1.0X). The ligated products were selected via agarose gel electrophoresis and PCR amplified. Then sequenced on the Illumina Novaseq6000 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) by Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co. (Guangzhou, China).

Analysis of RNA-seq data

Reads obtained from the sequencing machines include raw reads that contain adapters or low-quality bases. Therefore, the raw reads were further filtered using fastp (version 0.18.0) to obtain high-quality clean reads. Fastp removed reads containing adapters, those with more than 10% unknown nucleotides (N), and low-quality reads that contained more than 50% low-quality bases (Q-value < 20). The short read alignment tool Bowtie2 (version 2.2.8) was employed to map the reads to the ribosome RNA (rRNA) database. Subsequently, the reads mapped to rRNA were removed. The clean reads were then mapped to the C. camphora genome using HISAT2, which served as the reference genome21.

DEGs analysis

The mapped reads of each sample were assembled by using StringTie (v1.3.1) in a reference-based approach. For each transcription region, a FPKM value was calculated to quantify its expression abundance and variations by RSEM software. The DEGs between GL and RL were analyzed by DESeq2 software. The genes/transcripts with the parameter of p-value < 0.05 and |log 2 (fc)| ≥ 1 were considered DEGs. The DEGs were subjected to enrichment analysis of GO functions and KEGG pathways56. All DEGs were mapped to GO terms in the Gene Ontology database (http://www.geneontology.org/), gene numbers were calculated for every term, significantly enriched GO terms in DEGs comparing to the genome background were defined by hypergeometric test. The calculated p-value were gone through FDR Correction, taking FDR ≤ 0.05 as a threshold. GO terms meeting this condition were defined as significantly enriched GO terms in DEGs. KEGG is the major public pathway-related database57,58. Pathway enrichment analysis identified significantly enriched metabolic pathways or signal transduction pathways in DEGs comparing with the whole genome background. The calculating formula is the same as that in GO analysis.

Analysis of TFs expression differences

Genes were annotated with transcription factors using TFDB 4.0 (https://planttfdb.gao-lab.org/). Based on the number of MYB domains searched by InterProScan, MYB, MYB-like, and G2-like DEGs were classified to 1R-MYBs (MYB-related), R2R3-MYBs, 3R-MYBs, and 4R-MYBs. The DEGs of bHLH were performed cluster analysis based on the Xue et al.59 results. DEGs sequence similarity searches against the Arabidopsis proteome TAIR 10 meet bit-score ≥ 90 as significant matches. The heatmaps were draw by TBtools-II.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Six DEGs were selected for validation expression levels using qRT-PCR. The qRT-PCR assay was performed on a CFX Connect™ Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, USA) utilizing the ChamQ Blue Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme). The primer sequences (listed in Supplementary Table S5) were designed using Primer Premier 6.0 software. The reaction system contained 10 µL of ChamQ Blue Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix, 0.4 µL Primer 1 (10 nM), 0.4 µL primer 2 (10 nM), 30 ng of cDNA, and nuclease-free water to achieve a final volume of 20 µL per reaction. CcActin served as the reference gene for the qRT-PCR analysis23. Data analysis was performed using Bio-Rad CFX Manager 3.1 (Bio-Rad, USA). All experiments were performed with three biological replicates, and the 2−ΔΔCt method was employed to analyze the amplification results.

Protein extraction and protein content determination

0.4 g leaf samples from GL, RL, and WRL were individually ground into a fine powder using 10% PVP in liquid nitrogen. Protein extraction was carried out using the TCA/acetone precipitation method60. Subsequently, the protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method61.

Data availability

All raw sequencing data described in this study have been submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA). The Submission ID is SUB14435641, and the BioProject ID is PRJNA1110619. The collection of plant materials complied with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation. Authors comply with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

References

Yang, J., Wang, X. R. & Zhao, Y. Leaf color attributes of urban colored-leaf plants. Open. Geosci. 14, 1591–1605 (2022).

Mattila, H. & Tyystjärvi, E. Red pigments in autumn leaves of Norway maple do not offer significant photoprotection but coincide with stress symptoms. Tree Physiol. 43, 751–768 (2023).

Mei, H., Zhang, X., Zhao, F., Ruan, R. & Fu, Q. Integrated metabolome and transcriptome analysis provides insight into the leaf color change of Cymbidium ensifolium. Acta Physiol. Plant. 46, 50 (2024).

Tian, X. et al. Transcriptomic and metabolic analysis unveils the mechanism behind leaf color development in Disanthus cercidifolius var. longipes. Front. Mol. Biosci. 11, 1343123 (2024).

Liu, G. et al. Integrated transcriptome and biochemical analysis provides new insights into the leaf color change in Acer fabri. Forests 14, 1638 (2023).

Matile, P. Biochemistry of Indian summer: Physiology of autumnal leaf coloration. Exp. Gerontol. 35 (2), 145–158 (2000).

Sun, T. et al. Carotenoid metabolism in plants: The role of plastids. Mol. Plant. 11 (1), 58–74 (2018).

Tanaka, Y., Sasaki, N. & Ohmiya, A. Biosynthesis of plant pigments: Anthocyanins, betalains and carotenoids. Plant. J. 54 (4), 733–749 (2008).

Qu, S., Li, M., Wang, G., Yu, W. & Zhu, S. Transcriptomic, proteomic and LC-MS analyses reveal anthocyanin biosynthesis during litchi pericarp browning. Sci. Hortic. 289, 110443 (2021).

Khan, I. A. et al. Identification of key gene networks controlling anthocyanin biosynthesis in peach flower. Plant. Sci. 316, 111151 (2022).

Zhang, G., Yang, X., Xu, F. & Wei, D. Combined analysis of the transcriptome and metabolome revealed the mechanism of petal coloration in Bauhinia variegata. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 939299 (2022).

Wang, R. et al. Integration of metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses reveals the molecular mechanisms of flower color formation in Prunus mume. Plants 13, 1077 (2024).

Wu, Y., Han, T., Lyu, L., Li, W. & Wu, W. Research progress in understanding the biosynthesis and regulation of plant anthocyanins. Sci. Hortic. 321, 112374 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Characterization of blueberry glutathione S-transferase (GST) genes and functional analysis of VcGSTF8 reveal the role of ‘MYB/bHLH-GSTF’ module in anthocyanin accumulation. Ind. Crop Prod. 218, 119006 (2024).

Manzoor, M. A. et al. Flavonoids: A review on biosynthesis and transportation mechanism in plants. Funct. Integr. Genomic. 23, 212 (2023).

Li, C., Yu, W., Xu, J., Lu, X. & Liu, Y. Anthocyanin biosynthesis induced by MYB transcription factors in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 11701 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. PdMYB118, isolated from a red leaf mutant of Populus deltoids, is a new transcription factor regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis in poplar. Plant. Cell. Rep. 38, 927–936 (2019).

Han, H. et al. Genome-wide characterization of bZIP gene family identifies potential members involved in flavonoids biosynthesis in Ginkgo biloba L. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 23420 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Genome-wide identification and bioinformatics analysis of the WRKY transcription factors and screening of candidate genes for anthocyanin biosynthesis in azalea (Rhododendron simsii). Front. Genet. 14, 1172321 (2023).

Qi, F. et al. Functional analysis of the ScAG and ScAGL11 MADS-box transcription factors for anthocyanin biosynthesis and bicolour pattern formation in Senecio cruentus ray florets. Hortic. Res. 9, uhac071 (2022).

Shen, T. et al. The chromosome-level genome sequence of the camphor tree provides insights into Lauraceae evolution and terpene biosynthesis. Plant. Biotechnol. J. 20, 244–246 (2022).

Zhong, Y. et al. Transcriptome and metabolome analyses reveal a key role of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway cascade in the pigmentation of a Cinnamomum camphora red bark mutant (‘Gantong 1’). Ind. Crop Prod. 175, 114236 (2022).

Luan, X. et al. Genome-scale identification, classification, and expression profiling of MYB transcription factor genes in Cinnamomum camphora. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 14279 (2022).

Song, X. et al. Molecular and metabolic insights into anthocyanin biosynthesis during leaf coloration in autumn. Environ. Exp. Bot. 190, 104584 (2021).

Cech, T. R. Structural biology-The ribosome is a ribozyme. Science 289 (5481), 878–879 (2000).

Liu, X. et al. Comparative transcriptome sequencing analysis to postulate the scheme of regulated leaf coloration in Perilla frutescens. Plant. Mol. Biol. 112 (3), 119–142 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Pigment diversity in leaves of caladium × hortulanum birdsey and transcriptomic and metabolic comparisons between red and white leaves. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (1), 605 (2024).

Yang, C. et al. Analysis of flavonoid metabolism of compounds in succulent fruits and leaves of three different colors of Rosaceae. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 4933 (2024).

Koes, R., Verweij, W., Quattrocchio, F. & Flavonoids A colorful model for the regulation and evolution of biochemical pathways. Trends Plant. Sci. 10 (5), 236–242 (2005).

Gao, Y. F. et al. De novo transcriptome sequencing and anthocyanin metabolite analysis reveals leaf color of Acer pseudosieboldianum in autumn. BMC Genom. 22 (1), 383 (2021).

Zhou, X. et al. Metabolome and transcriptome profiling reveals anthocyanin contents and anthocyanin-related genes of chimeric leaves in Ananas comosus var. bracteatus. BMC Genom. 22(1), 331 (2021).

He, Q., Xue, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, N. & Zhang, L. Metabolic profiling and transcriptomic data providing critical flavonoid biosynthesis mechanisms disclose color differences of purple heading Chinese cabbages (Brassica rapa L). LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 168, 113885 (2022).

Zhou, Y., Wu, X. X., Zhen, Z. & Gao, Z. H. Identification of differentially expressed genes associated with flower color in peach using genome-wide transcriptional analysis. Genet. Mol. Res. 14 (2), 4724–4739 (2015).

Jiao, B., Meng, Q. & Lv, W. Roles of stay-green (SGR) homologs during chlorophyll degradation in green plants. Bot. Stud. 61 (1), 25 (2020).

Sakuraba, Y., Kim, Y. S., Yoo, S. C., Hörtensteiner, S. & Paek, N. C. 7-Hydroxymethyl chlorophyll a reductase functions in metabolic channeling of chlorophyll breakdown intermediates during leaf senescence. Biochem. Bioph Res. Co. 430 (1), 32–37 (2013).

Rong, H. et al. The Stay-Green Rice like (SGRL) gene regulates chlorophyll degradation in rice. J. Plant. Physiol. 170 (15), 1367–1373 (2013).

Xiang, C., Liu, J., Ma, L. & Yang, M. Overexpressing codon-adapted fusion proteins of 4-coumaroyl-CoA ligase (4CL) and stilbene synthase (STS) for resveratrol production in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J. Appl. Phycol. 32 (3), 1669–1676 (2020).

Ma, Z. H., Nan, X. T., Li, W. F., Mao, J. & Chen, B. H. Comprehensive genomic identification and expression analysis 4CL gene family in apple. Gene 858, 147197 (2023).

Mushtaq, M. A. et al. Comparative leaves transcriptome analysis emphasizing on accumulation of anthocyanins in Brassica: Molecular regulation and potential interaction with photosynthesis. Front. Plant. Sci. 7, 311 (2016).

Vangelisti, A. et al. Red versus green leaves: Transcriptomic comparison of foliar senescence between two Prunus cerasifera genotypes. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 1959 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Molecular and metabolic insights into anthocyanin biosynthesis for leaf color change in Chokecherry (Padus virginiana). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (19), 10697 (2021).

Gao, J. et al. Comparative metabolomic analysis reveals distinct flavonoid biosynthesis regulation for leaf color development of Cymbidium sinense ‘Red Sun’. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (5), 1869 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Characterization of blueberry glutathione S-transferase (GST) genes and functional analysis of VcGSTF8 reveal the role of ‘MYB/bHLH-GSTF’ module in anthocyanin accumulation. Ind. Crop Prod. 218, 119006 (2024).

Yin, D. Regulation mechanism RcGSTF11 on anthocyanin biosynthesis in Ricinus Communis L. Inner Mongolia Minzu Univ., 1–37 (2023).

Xu, W., Dubos, C. & Lepiniec, L. Transcriptional control of flavonoid biosynthesis by MYB-bHLH-WDR complexes. Trends Plant. Sci. 20 (3), 176–185 (2015).

Allan, A. C. & Espley, R. V. MYBs drive novel consumer traits in fruits and vegetables. Trends Plant. Sci. 23 (8), 693–705 (2018).

Zhang, Y., Fang, Z., Ye, X. & Pan, S. Identification of candidate genes involved in anthocyanin accumulation in the peel of jaboticaba (Myrciaria cauliflora) fruits by transcriptomic analysis. Gene 676, 202–213 (2018).

Kazemitabar, S. K., Faraji, S. & Najafi-Zarrini, H. Identification and in silico evaluation of bHLH genes in the Sesamum indicum genome: Growth regulation and stress dealing specially through the metal ions homeostasis and flavonoid biosynthesis. Gene Rep. 19, 100639 (2020).

Alabd, A. et al. Light-responsive transcription factor PpWRKY44 induces anthocyanin accumulation by regulating PpMYB10 expression in pear. Hortic. Res. 9, uhac199 (2022).

Dong, X. et al. Physiological and anatomical differences and differentially expressed genes reveal yellow leaf coloration in Shumard oak. Plants-Basel 9 (2), 169 (2020).

Hong, H. T., Netzel, M. E. & O’Hare, T. J. Optimisation of extraction procedure and development of LC-DAD-MS methodology for anthocyanin analysis in anthocyanin-pigmented corn kernels. Food Chem. 319, 126515 (2020).

Zhang, X. K. et al. HPLC-MS/MS-based targeted metabolomic method for profiling of malvidin derivatives in dry red wines. Food Res. Int. 134, 109226 (2020).

Smith, C. A., Want, E. J., O’Maille, G., Abagyan, R. & Siuzdak, G. X. C. M. S. Processing mass spectrometry data for metabolite profiling using nonlinear peak alignment, matching, and identification. Anal. Chem. 78 (3), 779–787 (2006).

Navarro-Reig, M., Jaumot, J., García-Reiriz, A. & Tauler, R. Evaluation of changes induced in rice metabolome by Cd and Cu exposure using LC-MS with XCMS and MCR-ALS data analysis strategies. Anal. Bioanal Chem. 407 (29), 8835–8847 (2015).

Gagnebin, Y. et al. Metabolomic analysis of urine samples by UHPLC-QTOF-MS: Impact of normalization strategies. Anal. Chim. Acta. 955, 27–35 (2017).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. K. E. G. G. Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587–D592 (2023).

Xue, G. et al. Genome-wide characterization and analysis of bHLH transcription factors related to anthocyanin biosynthesis in Cinnamomum camphora (‘Gantong 1’). Int. J. Med. Sci. 24, 3498 (2023).

Zhou, Y., Wu, X., Zhang, Z. & Gao, Z. Comparative proteomic analysis of floral color variegation in peach. Biochem. Bioph Res. Co. 464, 1101–1106 (2015).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32001358) and the Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (SJCX24_2136).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XW conceived and designed this study. YL and TD performed the transcriptome and qRT-PCR assays. FT, LK, and BP were responsible for determining the color parameters and pigment concentrations. XW, YL, and LK analyzed the data and draw the figures. XW and WZ wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, X., Li, Y., Du, T. et al. Transcriptome sequencing and anthocyanin metabolite analysis involved in leaf red color formation of Cinnamomum camphora. Sci Rep 14, 31470 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83235-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83235-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Transcriptomic analysis uncovers the red leaf coloration mechanism in Euonymus sacrosancta Koidz

Journal of Forestry Research (2025)