Abstract

The incident angle of seismic waves influences the dynamic response of rock slopes. However, the relationship between the back-slope effect in strong earthquake areas and the incident angle has not been well-explained. Based on the equivalent nodal force method and the viscoelastic artificial boundary theory, the oblique incidence of seismic P-wave and SV-wave are carried out in FLAC3D software. The accuracy of the proposed method is verified by comparing it with the results of the theoretical solution and another numerical result. The dynamic response of trapezoidal canyon slope under oblique incidence of P-waves and SV-waves was studied, and the effects of different slope angles and canyon widths were analyzed. The study reveals a pronounced back-slope effect under the action of the P-wave and SV-wave, and the slope’s horizontal direction dynamic response plays an important role. At the same location on the slope surface, the relative horizontal acceleration of the slope increases with the incident angle of P-waves and SV-waves, and the maximum value on the back-slope side is approximately 19 times and 6.8 times that of the front-slope side, respectively. Slope angle significantly affects the back-slope side’s dynamic response, showing an increase with increasing slope angle, while canyon width has a limited impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, destructive earthquakes have occurred frequently around the world. In 2022 alone, there were 112 earthquakes of Ms 6.0 and above globally1. Earthquakes are among the natural disasters causing the most severe casualties. It has the characteristics of suddenness, transient, wide range of disasters, and difficulty in prediction, which poses a serious threat to the safety of people’s lives and property and major projects, especially in the active tectonic area2. The alpine canyon is the most common natural geomorphology in the Three Rivers Basin of China. Due to river incision and crustal uplift, as well as the difference in lithology between the two sides of the canyon, there are significant variations in canyon width and the slope angles of the canyon sides, which are characterized by narrow to wide canyons, and steep slopes to gentle slopes. Meanwhile, the stability of the slopes on both sides of the canyon terrain is of great significance to ensure the safety of the buildings in the canyon. Therefore, it is necessary to further understand the dynamic response of canyon terrain in strong earthquake areas, which has important theoretical and engineering significance for guiding the seismic fortification of earthquake-induced landslides.

Owen et al.3 and Sato et al.4 observed an interesting phenomenon during the co-seismic landslides triggered by the 2005 Kashmir earthquake in Pakistan (Ms 7.6). They found that on the gully slopes nearly perpendicular to the seismic fault zone, the number of landslides on the side facing away from the seismic source is higher than on the side facing toward the source. Some scholars5,6,7,8 analyzed the distribution of landslides in the strong earthquake area of the Wenchuan earthquake and found that the density of landslides on the back-slope side of the slope is significantly higher than that on the front-slope side of the slopes. Xu et al.9,10 defined this phenomenon as the ‘back-slope effect’ of the slopes. Similar phenomena have been found in other strong earthquake regions11,12. For example, Wang et al.13 analyzed the spatial distribution of co-seismic landslides in Jiuzhaigou, and found that the left-bank landslide area of three river valleys near the seismic faults (Danzou Gou, Rize Gou, and Zechawa Gou) was significantly larger than the right-bank landslide area; Xu et al.14 found that the landslides with dip direction towards the East and Southeast have a higher distribution. By summarizing and analyzing co-seismic landslides around the world, Zhou et al.15 concluded that the back-slope effect is related to the double-reflected tension waves caused by compression waves, which is consistent with Tang et al.16. Huang et al.17 propose that the cause of this phenomenon is attributed to the “hanging wall effect” of the seismogenic fault. From the perspective of the seismic wave propagation process, near-fault seismic waves are still dominated by body waves when propagating to the Earth’s surface due to the closer distance from the source, while far-field seismic waves are dominated by surface waves. As seismic body waves propagate from the source, they do not enter the slope surface vertically at the bottom of the slope but at a certain angle. This leads to different angles of seismic waves to the back-slope side and front-slope side and generates different dynamic fields18.

The current research on seismic wave incidence angle mainly focuses on theoretical and numerical calculation methods. In terms of theoretical calculation methods, some scholars have investigated the analytical solutions of symmetric V-shaped or U-shaped canyons under the oblique incidence of SH waves based on the wave function expansion method19,20,21,22,23,24,25. However, the seismic waves used in the analytical solution are mostly simple harmonic waves with one period, which ignores the superposition and interference between the incident seismic waves and the reflected seismic waves in the model. Numerical calculation methods can input different types and frequencies of seismic waves based on satisfying the theoretical solution, which is very suitable for studying the dynamic response of slopes under oblique incidence. Therefore, some scholars have used different numerical computation methods to study the dynamic response and stability of various structural types under oblique incidence of seismic waves, and some research results have been obtained26,27,28. Related scholars also analyzed the influence of the rock layer, slope height, and slope angle on the dynamic response of single-face rock slopes under the oblique incidence of P-waves, SV-wave, and P-SV waves. They found that the most destructive incidence direction of slopes was approximated to be perpendicular to the slope surface instead of the vertical direction29; with the increase of slope height, the horizontal dynamic response is affected by the slope higher than the vertical direction30; the effect of SV-wave on the dynamic response of the slope is significantly stronger than that of P-wave31,32; the location of the soft and hard interfaces, and the wave impedance ratio have a significant effect on seismic landslides33.

The numerical models of slope used in the above studies on oblique incidence mainly focus on single-sided slopes, studies on the dynamic response of canyon-type slopes under seismic P-waves and SV-waves have primarily focused on vertical or horizontal wave incidences, with relatively fewer investigations on oblique wave incidences. For instance, Valdi et al.34 observed that under vertically incident seismic waves, vertical accelerations and displacement response spectra decrease in the central and lateral parts of the valley as the canyon slope steepens, respectively. Li et al.35 analyzed the V-shaped canyons under vertical incident of SV-waves, noting stress distribution around V-shaped valleys correlated with frequency. Some researchers have analyzed the dynamic response of canyon slopes under oblique incidence of seismic waves. For example, Li et al.36 utilized the boundary element method to analyze the seismic dynamic response of alpine canyon terrains under the influence of P-waves and SV-waves, exploring the effects of wave type, frequency, incidence angle, and geometric parameters of mountains and canyons on seismic amplification effects in complex terrains. Shen et al.37 studied the dynamic response of trapezoidal canyons under obliquely incident SV-waves, highlighting that change in slope angle have the greatest impact on slope dynamic responses. However, these studies did not analyze the back-slope effect or explore its formation mechanisms. Therefore, there remains a need for further research into the dynamic response, influencing factors, and instability mechanisms related to the back-slope effect of trapezoidal canyon slopes.

In summary, current research on the dynamic response of trapezoidal canyon slopes has predominantly focused on vertical or horizontal wave incidences, with relatively few studies focusing on oblique incidence. Most studies on obliquely incident seismic waves are centered on single-sided slopes, with few investigations into trapezoidal canyon slopes. Hence, it is crucial to explore the back-slope effect of trapezoidal canyons and its influencing factors under the oblique incidence of seismic waves. Slope stability is an external manifestation of slope dynamic responses, analyzing slope dynamic responses under strong seismic actions is crucial for revealing slope instability mechanisms. This paper aims to unveil the intrinsic mechanisms of the back-slope effect by analyzing the dynamic responses of trapezoidal canyon slopes under different incident angles. Firstly, seismic waves are transformed into equivalent nodal forces on boundaries using the equivalent nodal force method and consistent viscoelastic artificial boundary theory. The oblique incidences of seismic P-waves and SV-waves are implemented using Fish language in FLAC3D. Secondly, the effectiveness and accuracy of the proposed method are validated through comparisons with theoretical solutions and results from other numerical methods. Subsequently, a study on the dynamic response of the back-slope side and front-slope side under different incident angles of P-waves and SV-waves is conducted. Finally, the study explores the impacts of different slope angles and canyon widths on the dynamic response of trapezoidal canyon slopes. This study has practical significance in guiding the dynamic stability analysis and seismic protection of structures in alpine valley regions, such as dams and reservoir bank slopes.

Method

Viscous-elastic artificial boundary

To enhance computational efficiency in dynamic numerical simulation, the viscous-elastic artificial boundary is established by setting up a series of springs and dampers along the boundary. The coefficients of the elastic spring and damper are defined as follows38,39:

where A and B are the correction coefficients; the values of the coefficients are 0.8and 1.0, respectively40; \(\rho\) is the mass density; R is the distance from the wave source to the boundary; cp and cs are the velocities of the compression wave and shear wave in the medium, respectively; G is the shear modulus; and subscripts T and N indicate the tangential and normal directions of the elastic spring and damper, respectively.

The total wave field at artificial boundaries can be decomposed into the incident wave field and the scattered wave field41,43. The incident wave field is converted into equivalent nodal loads applied at the model boundary, while the scattered wave field is directly absorbed by the viscous-elastic artificial boundary. The equivalent nodal forces applied to boundary nodes can be expressed as32,42:

where Kli and Cli are the stiffness and damping coefficients that can be calculated by Eq. (1) and Eq. (2);\({u_{li}}\), \({\dot {u}_{li}}\) and \({\sigma _{li}}\) are the displacement, velocity and stress of input motions, respectively; Al is the influence area of node l on the artificial boundary.

Equivalent nodal forces for P-wavs and SV-waves

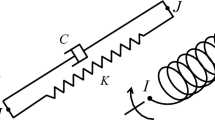

Assuming a P-wave propagating with an angle α (Fig. 1A), which reflects off the free surface of the ground, producing a reflected P-wave with an angle \(\alpha\) and a reflected SV-wave with an angle \(\beta\). According to Snell’s law43, the reflection coefficients of the P-wave and SV-wave, as well as the SV-wave reflection angle, are given by Eq. (4):

In the above equation, A1 is the amplitude ratio of reflected P-wave to incident P-wave, and A2 is the amplitude ratio of reflected SV-wave to incident P-wave.

Similarly, the primary parameters of reflection seismic waves for the SV-wave propagating with an angle \(\gamma\) (Fig. 1B) are given by Eq. (5):

where, B1 is the amplitude ratio of reflected P-wave to incident SV-wave, and B2 is the amplitude ratio of reflected SV-wave to incident SV-wave.

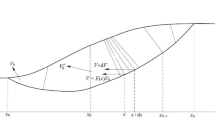

According to the reflection law of P-wave at the free surface, the decomposition of the free wave field on the model due to the oblique incidence of P-wave can be described as shown in Fig. 2. The free wave field at arbitrary nodes on the left and right boundaries is composed of incident P-wave with an angle \(\alpha\), the reflected P-waves with an angle \(\alpha\), and the reflected SV-wave with an angle \(\beta\). The free wave field at arbitrary nodes on the bottom boundary consists of the incident P-wave with an angle \(\alpha\). Using the equivalent force method, determining the displacement, velocity, and stress at different boundary nodes. Then, substituting these values into Eq. (3) to obtain the equivalent nodal forces at different boundaries.

The schematic diagram of the P wave arriving at the truncated boundary44.

Based on the same analysis approach, the decomposition method of the free wave field on the model when the oblique incidence of SV-wave, as well as the equivalent nodal forces on the left, right, and bottom boundaries, can be derived, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

The schematic diagram of the SV-wave arriving at the truncated boundary44.

Model validation

This study employs a truncated rectangular domain to simulate the propagation process of obliquely incident seismic waves in a semi-infinite field, as illustrated in Fig. 4A. The dimensions of the truncated regions under the oblique incidence of P-waves and SV-waves are 800 m × 400 m × 50 m and 2000 m × 1000 m × 50 m, respectively. Different model sizes are set to facilitate comparison with other numerical results. This domain size is sufficiently large to capture the propagation of all incident and reflected waves. The incident angles for P-waves and SV-waves are assumed to be 30° and 20°, respectively.

Assuming the study area is a homogeneous elastic medium, the mechanical parameters of the model are as follows: For P-waves: Young’s modulus E is 1.25 GPa; Mass density \(\rho\) is 2000 kg/m³; Poisson’s ratio ν is 0.25. Shear wave velocity cs and compressional wave velocity cp are 500 m/s and 866 m/s, respectively. For SV-waves: Young’s modulus E is 6 GPa; Mass density \(\rho\) is 2450 kg/m2; Poisson’s ratio ν is 0.3. Shear wave velocity cs and compressional wave velocity cp are 971 m/s and 1816 m/s, respectively. The input seismic wave is a pulse waves, as shown in Fig. 4B. The displacement equation for the input seismic wave is defined as follows37,45:

where \(H(\zeta )\) is the Heaviside function, P0 is the peak value of an impulse wave, and the value is 1.0 m; and T0 is the acting time of the impulse wave, where T0 = 0.3s; the total loading time is 2.5s.

Figure 5 shows the displacement contours of the incident P-waves at different moments. It can be seen that the propagation process of the incident and reflected waves on the ground is effectively modeled in a semi-infinite field. Furthermore, from the displacement time history curves of each measurement point, as shown in Fig. 6, it can be observed that the displacement time history curves of each measurement point under the action of P-waves almost coincide with the theoretical solution, and this result also coincides with the results obtained in the literature45 based on the finite element method, which confirms that the input method is effective and accurate in semi-infinite fields.

Figure 7 shows the displacement contours of the incident SV-wave at different moments. It can be seen that the propagation process of both the incident wave and the wave reflected by the surface in the semi-infinite field can be effectively modeled, and the angles of incidence and reflection are consistent with the theoretical solution. In addition, the displacement time history curves of each measurement point shown in Fig. 8, coincide with the results obtained based on the finite elements method in the literature37, confirming that the input method of SV-wave is effective and accurate in semi-infinite fields.

Results

It is assumed that the material of the rock slope is an elastic, homogeneous and isotropic medium with a density \(\rho\) of 2650 kg/m3, Young’s modulus E of 40 Gpa, and Poisson’s ratio v of 0.25. Material damping is not considered. Four slope models with different canyon widths were established, and the canyon widths were set as 20 m, 50 m, 80 m, and 100 m respectively, representing narrow and wide canyon types. The slope angles are set to 30°, 45°, and 60°, representing the change from gentle to steep slopes in real slopes. The schematic diagram of the trapezoidal canyon model is show in Fig. 9A. The input wave is a windowed simple harmonic wave, as shown in Fig. 9B. The windowed simple harmonic wave can avoid the shock effect46 due to the non-zero initial velocity, and its velocity is defined as follows:

where V0 is the peak velocity of the input wave; f0 is the main frequency of the input wave; and T0 is the seismic wave action time. A windowed simple harmonic wave with an amplitude of 0.1 m/s and a central frequency of 4 Hz is selected as the incident wave.

Seismic response under the action of P-wave

A trapezoidal canyon slope with a width of 50 m and a slope angle of 45° is taken as an example to study the dynamic response of the trapezoidal canyon slope under the action of seismic P-waves with different incidence angles.

Figure 10 shows the horizontal and vertical peak acceleration cloud maps of the slope under different incident angles of P-waves. It can be seen from Fig. 10A that when the incident angle of P-waves is lower than 30°, the horizontal peak acceleration cloud maps of the front-slope and the back-slope side are almost symmetrical. However, when the incidence angle is higher than 30°, the horizontal peak acceleration of the back-slope side is obviously higher than that of the front-slope side, indicating a pronounced back-slope effect. In contrast, the vertical peak acceleration cloud maps of the side slopes under different incident angles of P-waves, shown in Fig. 10B, reveal that the vertical peak accelerations on both sides of the slope are generally symmetrical. The peak vertical acceleration on the back-slope side is slightly higher than that on the front-slope side, suggesting that the back-slope effect is not significant in the vertical direction.

Figure 11 illustrates the variation trends of peak accelerations with elevation at the slope surface measurement point under different incident angles of P-waves. Figure 11A shows the horizontal peak acceleration on the front-slope and back-slope side. It can be observed that, for the same incident angle, the peak accelerations on the back-slope sides increase with the increase of the slope elevation, demonstrating an obvious elevation amplification effect47. The maximum value occurs at the slope shoulder position as the incidence angle is 75°, approximately 4.8 times that of the input wave amplitude. It also can be seen that, from the front-slope side, the peak acceleration increases with the increase of elevation, and the maximum value occurs at the slope shoulder position as the incidence angle is lower than 30°. However, when the incident angle exceeds 30°, the peak accelerations decrease with elevation, with the maximum value occurring at the slope toe. This behavior is distinctly different from the dynamic response of single-faced slopes under vertically incident seismic waves48. Figure 11B illustrates the vertical peak accelerations at slope surface monitoring points on both the back-slope and front-slope side. It can be observed that the vertical peak accelerations on both sides exhibit similar trends with changes in elevation and incident angle. When the incident angle is below 60°, the vertical peak accelerations increase with elevation, with the maximum value occurring at the slope shoulder position, demonstrating a clear elevation amplification effect. However, at an incident angle of 75°, the peak accelerations initially decrease and then increase with elevation, with the maximum value occurring at the slope toe. Overall, the peak accelerations on the front-slope side are slightly higher than those on the back-slope side.

Figure 12 shows the trends of horizontal and vertical peak accelerations at various monitoring points on both sides of the slope as the incident angle varies. It can be seen from Fig. 12A that the horizontal peak acceleration of the back-slope side increases with the increase of incidence angle, and reaches the maximum value between 60° and 75°. The horizontal peak accelerations of the front-slope side initially increase and then decrease with the increase of the incidence angle, except for the toe of the slope, the maximum peak acceleration occurs at the incidence angle of 30° ~ 45°. The reason for this phenomenon is that as the seismic P-wave incident angle increases, the horizontal energy of the seismic wave gradually increases, resulting in a gradual increase in horizontal acceleration. However, when the incident angle of a seismic wave exceeds a certain value, the scattering and reflection of the seismic wave at the slope angle of the front-slope side increases, which leads to a decrease in the energy transmitted to the inside of the slope, causing the horizontal acceleration decreases accordingly. As can be seen from Fig. 12B, the vertical acceleration of each measurement point on the back-slope side and the front-slope side has basically the same trend as the seismic P-wave incidence angle. It decreases with the increase of the incidence angle, and the vertical maxima and minima are basically the same on both sides, which indicates that the change of the P-wave incidence angle does not have a significant effect on the vertical dynamic response of the two sides of the slope. However, the peak acceleration of the measurement points below the middle of the slope increases slightly when the seismic P-wave incidence angle exceeds 60°. This may be due to the fact that when the seismic wave incidence angle is relatively large, the direction of the reflected wave from the slope surface - canyon - slope surface is changed during the propagation of the seismic wave, resulting in the concentration of seismic wave energy in the lower region of the slope.

Figure 13 shows the curves of the ratio of the peak acceleration at each measurement point on the back-slope side to those on the front-slope side change with the incidence angle of P-waves and slope elevation. As can be seen from Fig. 13A, when the seismic wave incidence angle is 0–15°, the horizontal relative peak acceleration is 1, indicating that the peak acceleration on both sides is basically the same. When the incidence angle is higher than 30°, the relative peak acceleration at each measurement point is greater than 1, indicating that the horizontal peak acceleration of the back-slope side is higher than the front-slope side. Meanwhile, the relative peak acceleration gradually increases with the increase of incidence angle and elevation. It indicates that, as the incident angle of P-waves and the elevation of the slope increase, the back-slope effect of the slope becomes more pronounced.

Figure 13B shows the variation curves of the relative peak acceleration values of the slope with the incidence angle and the slope elevation. It can be seen that when the P-wave is incident vertically, the relative peak acceleration at each measurement point is almost 1, which is consistent with the results of the symmetric slope. Except for the slope shoulder and 3/4 slope height locations at incidence angles of 60–75°, the vertical peak acceleration is less than 1 as the incidence angle increases, indicating that the peak acceleration on the back-slope side is less than that of the front-slope side. It is further shown that the slope back-slope effect is mainly affected by the horizontal dynamic response under the action of P-waves with different incidence angles.

Seismic response under the action of SV-wave

According to wave theory, incident SV-waves exhibit a critical angle \({\gamma _c}\)(\({\gamma _c} = {\sin ^{ - 1}}({c_s}/{c_p})\)), leading to the generation of inhomogeneous waves when the incident angle of SV-waves exceeds the critical angle. Based on the SV-wave critical angle formula and considering the mechanical parameters of rock slopes, the critical angle is calculated to be 37.3°. Therefore, in this study, SV-wave incident angles are set at 0°, 10°, 20°, and 30°. The slope model and mechanical parameters are consistent with those described in Sect. Seismic response under the action of P-wave.

Figure 14 shows the horizontal and vertical peak acceleration cloud maps of the slope under different SV-wave incidence angles. As shown in Fig. 14A, when the SV-wave is incident vertically, the horizontal peak acceleration of the back-slope and front-slope sides are nearly symmetrical. However, when the incident angle is inclined, the horizontal peak acceleration on the back-slope side of the model is higher than that on the front-slope side, and the slope has an obvious back-slope effect. It can be seen that from the vertical peak acceleration maps (see Fig. 14B) under different incidence angles of SV-wave, the vertical peak acceleration on both sides of the model generally exhibits a symmetrical trend. The peak accelerations on the back-slope side are slightly higher than those on the front-slope side, which differs from the vertical acceleration distribution observed under the oblique incidence of P waves.

Figure 15 shows the variation trends of peak accelerations with elevation at the slope surface measurement point on the front-slope and back-slope side under different incident angles of SV-waves. Figure 15A shows the horizontal peak acceleration on both sides of the model. It can be seen that the peak acceleration on the back-slope side increases with the increase of slope elevation under the same incidence angle, which shows an obvious elevation amplification effect49, and the maximum value occurs at the slope shoulder position, which is about 4.2 times of the input wave amplitude. It can be seen that, from the horizontal peak acceleration on the front-slope side, the acceleration increases with elevation in different trends under various SV-waves incident angles. When the incidence angle is vertical, the slope has an obvious elevation amplification effect; when the incidence angle is higher than 10°, the slope acceleration shows a decreasing trend with increasing elevation, and the maximum value appears at the toe of the slope. Overall, the horizontal peak acceleration on the back-slope side is significantly higher than that of those on the front-slope side.

Figure 15B illustrates the vertical peak accelerations at the slope surface measurement points on both sides of the slope. It can be observed that the peak accelerations on both sides exhibit similar trends with changes in elevation and incident angle. When SV-waves are incident vertically, the vertical accelerations initially increase and then decrease with elevation, reaching a maximum at the mid-slope position, approximately 0.4 times the input wave. As the incident angle of the SV-wave increases, the vertical peak accelerations on both sides of the slope decrease with increasing elevation, with the maximum value occurring at the slope toe. However, the vertical peak acceleration of the back-slope side is obviously higher than that of the front-slope side. This differs notably from the vertical dynamic response pattern of the slope under the oblique incidence of P-waves. That is to say, the vertical slope still has an obvious back-slope effect and shows a gully amplification effect under the oblique incidence of SV-wave.

Figure 16 shows the trend of horizontal and vertical peak acceleration with SV-wave incidence angle for the slope surface measurement points on the back-slope and front-slope sides. It can be seen from Fig. 16A that the horizontal peak acceleration of the back-slope side increases with the increase of incidence angle and reaches the maximum value of 4.2 at the incidence angle of 30°. The horizontal peak acceleration of the front-slope side decreases with the increase of incidence angle, and the maximum value of 2.2 occurs at the shoulder position when the SV-wave is incident vertically. Figure 16B shows that the vertical peak acceleration of the measurement points on both sides of the slope has slightly different trends with the incident angle of the SV-wave, and the back-slope side grows faster at a lower incident angle. However, the front-slope side has a faster growth rate at a higher incident angle. Overall, the acceleration of both sides of the measurement points increases with the increase of the incidence angle, and the vertical maxima and minima of both sides are generally the same.

Figure 17 shows the curves of the ratio of the peak acceleration at each measurement point on the back-slope side to those on the front-slope side change with the incidence angle of SV-waves and slope elevation. It can be seen that when the seismic SV-wave is incident vertically, the relative peak acceleration in the horizontal and vertical directions of the slopes is 1, which further indicates that the dynamic response is the same on both sides under vertical incidence when the lithology and slope geometry of the back-slope side and the front-slope side are not much different. With the increase of incidence angle, the horizontal relative acceleration at different elevations of the slope increases gradually, and the value is greater than 1. The vertical relative peak acceleration shows a trend of increasing and then decreasing, and its value is greater than 1. It is the largest when the incident angle of the SV-wave is 10°, and the vertical peak acceleration in the back-slope side is about 1.7 times that on the front-slope side. This indicates that under the oblique incidence of SV-waves, the back-slope effect of the slope is enhanced with the increase of elevation and incidence angle, which is similar to the results of the P-wave action.

Factor analysis

Based on the peak acceleration response of the slope in the horizontal and vertical directions under different incidence angles of P-waves and SV-waves, it can be seen that the variability of the dynamic response of the slopes in the horizontal direction is higher than that in the vertical direction. Therefore, to facilitate the analysis of the dynamic response of the slopes under different influencing factors, the total acceleration amplification coefficient is used to study the dynamic response of the slopes under different influencing factors. Define the total acceleration amplification coefficient of slope as the total peak acceleration of the measurement point to the peak acceleration of the input wave.

Effect of canyon width

Figure 18 shows the cloud maps of the acceleration amplification factor of the toe, the middle, and the shoulder of the slope locations under different canyon widths and incident angles of P-waves. It can be seen that when the incident angle of the P-wave is constant, the acceleration amplification factor of the middle and shoulder locations of the slope on both sides of the canyon are not significantly affected by the width of the canyon, with minimal variation in amplification factors as the canyon width changes. However, the dynamic response of the toe of the slope is significantly affected by the canyon width, especially when the incidence angle of the P-wave is relatively large, the acceleration amplification factor of the slope on the back-slope side increases with the increase of the canyon width, and decreases with the increase of the canyon width on the front-slope side. When the incident angle is lower than 45°, the effect of canyon width on the dynamic response at the toe of the slope is weakened.

Figure 19 shows the acceleration amplification factor at the toe, middle, and shoulder positions for different canyon widths and incident angles of SV-waves. It can be seen from Fig. 19A that when the incident angle is constant, the acceleration amplification factor on the back-slope side has no obvious change with the change of canyon width, indicating that the canyon width has a minimal impact on the dynamic response of the back-slope side under the action of SV-waves. Figure 19B shows that on the front-slope side, the amplification factor at the toe decreases with increasing canyon width but increases with increasing incident angle, reaching a maximum of about 2.2 when the incident angle is 30° and the canyon width is 20 m. The acceleration amplification coefficients of the middle and shoulder of the slope decrease with the increase of canyon width when the SV-wave incidence angle is higher than 10°, and increase with the increase of canyon width when the incidence angle is lower than 10°. The maximum value of acceleration amplification factor at the middle and shoulder of the slope occurs when the incident angle is 0° and the canyon width is 100 m, with peak values being approximately 1.96 times and 2.18 times the input wave amplitude, respectively.

Effect of slope angle

Figure 20 shows the cloud diagrams of the acceleration amplification factor at the toe, middle, and shoulder locations of the slope under different incident angles of P-waves and slope angles. It can be seen from Fig. 20A that when the incident angle is certain, the dynamic response of the back-slope side is greatly affected by the slope angle, and the acceleration amplification factor increases with the increase of the slope angle. The acceleration at the shoulder position reaches the maximum value, approximately 4.6 times the input wave amplitude when the incident angle of P-wave is 75° and the slope angle is 60°. As shown in Fig. 20B, when the incident angle is lower than 45°, the acceleration amplification factor of the three measurement points on the front-slope side is not significantly affected by the slope angle. When the incidence angle is higher than 45°, the acceleration amplification factor at the toe of the slope decreases with the increase of the slope angle, while it increases at the middle and the shoulder of the slope. Comparing the acceleration amplification coefficients on both sides of the slope at the same incidence angle, the dynamic response on the back-slope side is strongest when the incidence angle is larger and the slope is steeper; while the dynamic response on the front-slope side is strongest when the seismic P-wave is incident perpendicularly, and the slope is steeper.

Figure 21 illustrates the acceleration amplification factors at the toe, middle, and shoulder positions under different incident angles of SV-waves and slope angles. It can be observed from Fig. 21A that when the incident angle is constant, the dynamic response on the back-slope side is significantly influenced by the slope angle, with the acceleration amplification factor increasing as the slope angle increases. When the incident angle is 30° and the slope angle is 60°, the maximum acceleration at the shoulder position is approximately 4.2 times the input wave amplitude. Figure 21B shows that when the incident angle is less than 10°, the acceleration amplification factor at the middle and shoulder locations on the front-slope side is not significantly affected by the slope angle. When the incident angle exceeds 10°, the amplification factor increases with the slope angle, reaching a maximum value of approximately 2.2 when the incident angle is 30° and the slope angle is 60°. Comparing the acceleration amplification factor for the same incident angles on the back-slope and front-slope sides, it is evident that the dynamic response on the back-slope side is strongest when the incident angle is large and the slope is steep. Conversely, the dynamic response on the front-slope side is strongest when the SV-waves are vertically incident or when the incident angle is large, and the slope is steep.

Discussion

In this study, the accuracy of obliquely incident seismic waves was implemented and verified using the finite difference method. The research focused on the dynamic amplification effects of trapezoidal canyon slopes under oblique incidence of different types and incidence angle of seismic waves. Additionally, the study explored the influence of canyon width and slope angle on the dynamic response of the trapezoidal canyon slopes. The numerical results indicate that the incidence angle of seismic waves significantly affects the dynamic response and stability of the slopes.

The back-slope effect on near-fault slopes in strong earthquake regions, as observed during events like the Wenchuan earthquake, is a distinctive phenomenon. Currently, the interpretation of the back-slope effect is generally attributed to the fault ‘hanging wall / footwall effect’ and the seismic wave reflection multiplication effect16,17. Our study further reveals that the incidence angle of seismic waves is also a factor in this phenomenon on slopes. Under the action of P-waves and SV-waves at different incidence angles, the dynamic response on the back-slope side is consistently stronger than on the front-slope side. The reason for this phenomenon is that, under the same conditions, the seismic wave incident angle intersects the back-slope at a small angle and the front-slope at a larger angle. This results in the superposition of incident and reflected waves on the back-slope side during wave propagation, while the superposition effect between incident and reflected waves on the front-slope side is less pronounced, which ultimately leads to the different dynamical fields on both sides of the canyon. This is the primary reason why the peak acceleration on the back-slope side is higher than that on the front-slope side18. The obstruction effect of the canyon might weaken the superposition and interference of seismic waves on the front-slope side50,51. Additionally, the contribution of dynamic response in different directions of slope to back-slope effect is different under different incident wave types. Under oblique incidence of P-waves, the dominant effect is observed in the horizontal dynamic response of the slope. In contrast, under SV-wave influence, both horizontal and vertical dynamic responses exhibit higher values on the back-slope side compared to the front-slope side, with the horizontal response still playing a predominant role. This variation may be attributed to differences in the propagation direction of P-waves and SV-waves relative to the vibration direction.

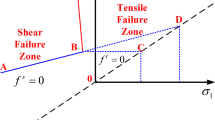

The canyon width has no significant effect on slope dynamic response in the research of Shen et al.37 under the action of SV-waves. In this paper, it is shown that canyon width is not significantly affected by canyon width, except for a significant effect on the dynamic response at the toe of the slope location. However, the slope angle and the incidence angle of seismic wave have a significant effect on the dynamic response between the back-slope side and the front-slope side. Since the seismic wave makes a small angle with the slope face of the back-slope side, when the incident angle is lower than the slope angle, the incident wave will be reflected by the surface and produce a wrap-around at the toe of the slope, and the seismic wave at the toe of the slope will propagate upward along the slope surface and superpose with the seismic wave generated at the surface at the shoulder of the slope (Fig. 22A). When the angle of incidence is larger than the slope angle of the slope, the incident seismic wave propagates forward along the ground surface and the slope surface (Fig. 22B), and the superposition of seismic waves at the slope shoulder does not occur. However, the reflection effect with the slope surface also leads to a significant increase in the dynamic response of the slope shoulder location.

The dynamic response of slopes is crucial for assessing slope seismic stability, engineering rock mass seismic design, and predicting earthquake-induced landslides48. When a certain location on a slope exhibits a strong dynamic response, it indicates that the slope is experiencing higher kinetic energy in that area. However, the direction of peak ground motion also plays a critical role in slope stability50. When the direction of peak ground motion aligns with the direction of seismic wave propagation (see Fig. 23A), the back-slope side of the slope experiences similar displacements. If these displacements are towards the canyon, it can exacerbate instability and failure of the slope. Conversely, for the front-slope side of the slope, where the overall displacement direction moves away from the canyon, it may enhance slope stability. On the other hand, when the direction of seismic wave propagation is opposite to the direction of displacement (see Fig. 23B), although the back-slope side experiences a stronger dynamic response, the slope’s stability on the back-slope side may be higher than that on the front-slope side due to displacement direction moving away from the canyon.

It is worth noting that the model used in this study is a generalized slope model, which only considers the dip angle of wavefronts and does not account for their strike. The seismic wave oblique incidence method employed in this study has limitations in analyzing three-dimensional models in practical scenarios. Furthermore, the amplification effect of seismic waves due to three-dimensional terrain or heterogeneities is higher than that in two-dimensional models51. However, since this study did not consider stratigraphic and three-dimensional effects, the seismic motion amplification in the numerical results may be underestimated. Therefore, further research involving these factors is necessary to explore the coupled effects of different factors on seismic amplification. The homogeneous elastic body model used in this study to investigate the fundamental laws of slope dynamic response meets the requirements. However, actual slopes consist of different rock compositions and numerous structural features, such as layer structure52,53, discontinuous joint planes54, etc. Hence, considering the nonlinear characteristics of rock slopes is crucial for seismic defense strategies in slopes.

Conclusion

This paper implements the seismic P-waves and SV-waves oblique incidence in FLAC3D software based on viscoelastic artificial boundary and equivalent loading methods. The dynamic response of trapezoidal canyon slopes under different types of seismic wave oblique incidence is investigated, and the influence of canyon width and slope angle on the back-slope effect is discussed. The main conclusions can be drawn from this research.

-

1.

At the same incident angle for P-wave and SV-wave, the horizontal peak acceleration on the back-slope side is more significant than that on the front-slope side. The maximum peak acceleration reaches approximately 19 times and 6.8 times that of the front-slope side under the influence of P-wave and SV-wave, respectively, indicating a significant back-slope effect. There is minimal vertical peak acceleration difference between the slope’s two sides.

-

2.

The back-slope effect of the slope is primarily controlled by the dynamic response of the horizontal acceleration under the action of seismic P-waves. However, the back-slope effect is influenced by both the horizontal and vertical acceleration dynamic responses under the action of seismic SV-waves, and the horizontal acceleration dynamic response plays the dominant.

-

3.

The acceleration dynamic response of trapezoidal canyon slopes under different incident angles of seismic P-waves and SV-waves is different from that of single-face slopes. With the increase of the incident angle of P-waves and SV-waves, the horizontal acceleration dynamic response of the slopes gradually changes from elevation amplification effect to canyon amplification effect; the vertical acceleration dynamic response of the slopes under seismic P-waves show elevation amplification effect, while the slopes show canyon amplification effect under seismic SV-waves.

-

4.

The incidence angle of seismic waves significantly impacts the back-slope effect of the slope, becoming more pronounced as the incidence angle increases. Changes in canyon width notably affect the acceleration dynamic response at the slope toe but have less significant effects on other positions. The influence of slope angle on the dynamic response of trapezoidal canyon slopes is more significant than that of canyon width. As the slope angle increases, the back-slope effect of the slope becomes more evident.

Data availability

Except for the source code of the program written in this paper due information involving trade secrets, personal privacy, and other disclosure that may harm the legitimate rights and interests of third parties shall not be disclosed, all other experimental data are available upon request from the first author named Kunsheng Gu.

References

Xu, Y. H. & Xue, L. How hard do these countries try to outrun seismic waves? Shanghai NPC Monthly. 51–53. https://doi.org/10.16702/j.cnki.cn31-1590/d.2023.09.038 (2023).

Guo, M. Z., Gu, K. S. & Wang, C. Dynamic Response and Failure Process of a Counter-Bedding Rock Slope under Strong Earthquake Conditions. Symmetry 14, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14010103 (2022).

Owen, L. A. et al. Landslides triggered by the 8 October 2005 Kashmir earthquake. Geomorphology 94, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2007.04.007 (2008).

Sato, H. P. et al. Interpretation of landslide distribution triggered by the 2005 Northern Pakistan earthquake using SPOT 5 imagery. Landslides 4, 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-006-0069-5 (2007).

Li, Q., Wang, Y. S. & Jiang, F. S. Developmental pattern of the Wenchuan-earthquake-caused collapses on the Minjiang River from Yingxiu to Caopo. J. Geol. Hazards Environ. Preserv. 25, 31–36 (2014).

Li, W. L., Xu, Q. & Huang, R. Q. A preliminary study on the back-wave surface effect of Wenchuan earthquake landslides. J. Geol. 87, 294–295 (2013).

Zhang, P., Chen, X. & Wang, X. Analysis of near-fault ground motion and seismic landslide failure mode in Wenchuan earthquake. J. Nanjing U Techno (Nat Sci. Ed.) 31, 55–59 (2009).

Chigira, M., Wu, X., Inokuchi, T. & Wang, G. H. Landslides induced by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, Sichuan, China. Geomorphology 118, 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2010.01.003 (2010).

Xu, Q. & Li, W. L. Study on direction effects of landslides triggered by Wenchuan earthquake. Adv. Eng. Sci. 42, 7–14. https://doi.org/10.15961/j.jsuese.2010.s1.007 (2010).

Xu, Q., Zhang, S. & Li, W. L. Spatial distribution of large-scale landslides induced by the 5.12 Wenchuan earthquake. J. Mt. Sci. 8, 246–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-011-2105-8 (2011).

Shao, X. Y., Ma, S. Y. & Xu, C. Distribution and characteristics of shallow landslides triggered by the 2018 Mw 7.5 Palu earthquake, Indonesia. Landslides 20, 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-022-01972-x (2023).

Zhao, B. et al. Preliminary analysis of some characteristics of co-seismic landslides induced by the Hokkaido Iburi-Tobu earthquake (September 5, 2018), Japan. Catena 189, 104502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2020.104502 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Earthquake-triggered landslides affecting a UNESCO Natural Site: the 2017 Jiuzhaigou Earthquake in the World National Park, China. J. Mt. Sci. 15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-018-4823-7 (2018).

Xu, C. & Xiao, J. Z. Spatial analysis of landslides triggered by the 2013 MS7.0 Lushan earthquake: A case study of a typical rectangle area in the northeast of Taiping Town. Seismol. Geol. 35, 436–451. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.0253-4967.2013.02.021 (2013).

Zhou, H. F. et al. Dynamic Effect of Landslides Triggered by Earthquake: A Case Study in Moxi Town of Luding County, China. J. Earth Sci. 35, 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12583-022-1806-y (2024).

Tang, C. A., Zuo, Y. J. & Qin, S. F. Spalling and Slinging Pattern of Shallow Slope and Dynamics Explanation in the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. Proceedings of the 10th Conference on Rock Mech. Eng. China. 258–262. (2009).

Huang, R. Q. & Li, W. L. Fault effect analysis of Geo-hazard triggered by Wenchaun earthquake. J. Eng. Geol. 17, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-9665.2009.01.003 (2009).

Geng, P. C. Sudy on the effect Mechanism of seismic slope. (Xi’an University of Technology, 2017).

Amini, D., Gatmiri, B. & Maghoul, P. Seismic response of alluvial valleys subject to oblique incidence of shear waves. J. Earthq. Eng. 26, 6304–6328. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632469.2021.1913457 (2021).

Zhang, N., Gao, Y. F., Li, D. Y., Wu, Y. X. & Zhang, F. Scattering of SH waves induced by a symmetrical V-shaped canyon: a unified analytical solution. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 11, 445–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11803-012-0135-z (2012).

Gao, Y. F. et al. Effects of topographic amplification induced by a U-shaped canyon on seismic waves. B Seismol. Soc. Am. 102, 1748–1763. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120110306 (2012).

Zhang, F., Jia, S. L. & Shu, S. Effects of seismic amplification on the 3D stability of fill slopes in V-shaped valleys. Acta Geotech. 19, 3241–3255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-023-02167-x (2024).

Zhang, N. et al. Effect of a symmetric V-shaped canyon on the seismic response of an adjacent building under oblique incident SH waves. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 52, 1861–1883. https://doi.org/10.1002/eqe.3850 (2023).

Zhang, N., Gao, Y. F., Cai, Y. Q., Li, D. Y. & Wu, Y. X. Scattering of SH waves induced by a non-symmetrical V-shaped canyon. Geophys. J. Int. 191, 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2012.05604.x (2012).

Li, M. H., Yang, Z. L., Sun, M. H. & Yan, Y. Influence of canyon topography amplification effect and shielding effect on bridge seismic response. Arch. Appl. Mech. 93, 3327–3340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00419-023-02441-0 (2023).

García, F., Aznárez, J. J., Padrón, L. A. & Maeso, O. Relevance of the incidence angle of the seismic waves on the dynamic response of arch dams. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 90, 442–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2016.09.011 (2016).

Qiu, D. P., Chen, J. Y. & Xu, Q. Dynamic responses and damage forms analysis of underground large scale frame structures under oblique SV seismic waves. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 117, 216–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2018.11.032 (2019).

Wang, X. W., Chen, J. T. & Xiao, M. Seismic damage assessment and mechanism analysis of underground powerhouse of the Yingxiuwan Hydropower Station under the Wenchuan earthquake. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 113, 112–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2018.05.027 (2018).

Fan, G., Zhang, L. M., Li, X. Y., Fan, R. L. & Zhang, J. J. Dynamic response of rock slopes to oblique incident SV waves. Eng. Geol. 247, 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2018.10.022 (2018).

Cao, M. X., Ou, E., Yan, S. H. & Du, J. X. Seismic Response Analysis of Uplift Terrain under Oblique Incidence of SV Waves. Symmetry 14, 2244. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14112244 (2022).

Liu, B. & Zhang, B. Y. Dynamic Response of Rock Slopes under Obliquely Incident Seismic Waves. Adv. Civ. Eng. 8859584. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8859584 (2020).

Huang, J. Q. et al. Seismic stability of jointed rock slopes under obliquely incident earthquake waves. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 17, 527–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11803-018-0460-y (2018).

Jiao, H. Y. et al. Seismic response analysis of slope sites exposed to obliquely incident P waves. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 1057316. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.1057316 (2023).

Valdi, M. H. T., Atrechian, M. R., Shalkoohy, A. J. & Balasbaneh, A. T. Numerical study of seismic response of trapezoidal alluvial valleys against vertically propagating incident waves. J. Eng. Res. 7, 37–57 (2019).

Li, Z. L., Wu, W., Li, J. C. & Zhao, J. Dynamic tensile failure of a V-shaped canyon induced by vertically travelling SV waves. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 162, 107458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2022.107458 (2022).

Li, Z. L., Li, J. C., Liu, B. & Nie, M. M. Seismic motion amplification effect of shallow-cutting hill-canyon composite topography. J. Eng. Geo. 29, 137–150. https://doi.org/10.13544/j.cnki.jeg.2021-000 (2021).

Shen, H., Liu, Y. Q., Li, H. B. & Liu, B. Topographic Effects on the Seismic Response of Trapezoidal Canyons Subjected to Obliquely Incident SV Waves. J. Shock Vib. 3384829. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/3384829 (2023).

Zhu, H., Yan, S. H., Sun, W. Y. & Zhang, Y. L. Seismic response analysis of subway station under obliquely incident SV waves. Sci. Rep. 14, 9139. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59593-4 (2024).

Du, X. L., Zhao, M. & Wang, J. T. A stress artificial boundary in FEA for near-field wave problem. Chin. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 38, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.6052/0459-1879-2006-1-2004-442 (2006).

Liu, J. B., Du, Y. X., Du, X. L., Wang, Z. Y. & Wu J. 3D viscous-spring artificial boundary in time domain. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 1, 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11803-006-0585-2 (2006).

Liu, J. B., Wang, Z. Y., Du, X. L. & Du, Y. X. Three-dimensional visco-elastic artificial boundaries in time domain for wave motion problems. Eng. Mech. 22, 46–51 (2006).

He, J. T., Ma, H. F., Zhang, B. Y. & Chen, H. Q. Method and realization of seismic motion input of viscous-spring boundary. J. Hydraul Eng. 41, 960–969 (2020).

Pujol, J. et al. Elastic wave propagation and generation in seismology. Ma D T, Beijing: Seismological. (2003).

Shen, H. et al. Numerical evaluation of ground motion amplification of rock slopes under obliquely incident seismic waves. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 178, 108488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2024.108488 (2024).

Yin, C., Li, W. H. & Wang, W. Evaluation of ground motion amplification effects in slope topography induced by the arbitrary directions of seismic waves. Energies 14, 6744. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14206744 (2021).

Gu, K. S., Zhou, J., Dai, F. C. & Zhang, L. Q. Dynamic response analysis of single slope under oblique incidence of seismic P wave. Chin. J. Geophys. 67, 2350–2363. https://doi.org/10.6038/cjg2023R0013 (2024).

Bao, Y. J., Huang, Y. & Zhu, C. Q. Effects of near-fault ground motions on dynamic response of slopes based on shaking table model tests. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 149, 106869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2021.106869 (2021).

Qi, S. W., He, J. X. & Zhan, Z. F. A single surface slope effects on seismic response based on shaking table test and numerical simulation. Eng. Geol. 306, 106762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2022.106762 (2022).

Zhou, H. X., Che, A. L. & Zhu, R. J. Damage evolution of rock slopes under seismic motions using shaking table test. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 55, 4979–4997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-022-02921-9 (2022).

Chen, G. Q., Xia, M. Y., Thuy, D. T. & Zhang, Y. B. A possible mechanism of earthquake-induced landslides focusing on pulse-like ground motions. Landslides 18, 1641–1657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-020-01597-y (2021).

Zhang, X. L., Li, X. J., Zhou, Z. H., Chen, G. X. & Peng, X. B. The seismic response analysis of three-dimensional canyon complex topography under incident SV seismic waves. Chin. J. Geophys. 60, 2779–2790. https://doi.org/10.6038/cjg20170723 (2017).

Cheng, Y. et al. Micro-cracking morphology and dynamic fracturing mechanism of natural brittle sandstone containing layer structure under compression. Constr. Build. Mater. 425, 136051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136051 (2024).

Cheng, Y., Song, Z. P., Xu, Z. W., Yang, T. T. & Tian, X. X. Failure mechanism and infrared radiation characteristic of hard siltstone induced by stratification effect. J. Mt. Sci. 21, 1058–1074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-023-8444-4 (2024).

Song, D. Q., Zhang, S., Chun Liu, C. & Nie, W. Cumulative damage evolution of jointed slopes subject to continuous earthquakes: Influence of joint type on dynamic amplification effect and failure mode of slopes. Comput. Geotech. 166, 106016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2023.106016 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The presented study is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42277144, 41972287); National Key Research and Development Project of China (2019YFC1509703). These supports are gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

The presented study is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42277144, 41972287); National Key Research and Development Project of China (2019YFC1509703).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.G. Methodology, Software; Validation, Writing-original draft. J.Z. Methodology, Supervision, Review & editing. F.D. Validation, Review & editing. L.Z. Review & editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, K., Zhou, J., Dai, F. et al. Numerical study on the back slope effect of trapezoidal canyon slope under oblique incidence of P-SV waves. Sci Rep 14, 31513 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83247-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83247-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Dynamic Failure Analysis of Rock Slopes with Discontinuous Joints Under Obliquely Incident SV Waves Using a FDM–DEM Coupling Method

Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering (2025)