Abstract

Ecosystem service value (ESV) is essential for understanding regional ecological benefits and resources. This study utilizes the fourth phase of land use data from the Resource and Environment Science Data Centre of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. We corrected the ESV coefficient using the equivalent factor method for value per unit area and integrated the biomass factor of farmland ecosystems in Shaanxi Province. This allowed us to adjust the equivalent factor for China’s terrestrial ecosystem on a geographic scale. Based on these corrections, we analyzed changes in land use and the evolution of ecosystem service value over the past two decades in Xi’an, China. Our findings indicate that the proportions of cultivated and forest land in Xi’an remained stable from 2000 to 2020, despite an increase in construction land and a decrease in cultivated areas. Forest and unused lands remained stable, while grassland and water bodies fluctuated. The ESV related to land use in Xi’an increased by 938.8 million yuan during this period, with high-value areas primarily located in the forested regions south of the Qinling Mountains and along the Weihe, Bahe, and Chanhe Rivers. Low–value zones were concentrated in the urban core. This research enhances methodologies for quantifying urban ESV, providing vital support for land resource management, ecological conservation, and high-quality urban development in major cities in China. These findings will inform policy-making for sustainable urban growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Internationally, research increasingly emphasizes the integration of ecosystem service values into national accounting systems and policy frameworks, such as the United Nations’ System of Environmental-Economic Accounting (SEEA)1. These studies incorporate ecosystem service values into sustainability assessments and climate change mitigation strategies, highlighting their essential role in maintaining global ecological balance. Similarly, China’s efforts to build an ‘ecological civilization’ integrate ecosystem service values into national and regional planning, underscoring their significance in achieving sustainable development goals.

Ecosystem service refers to “the products and services provided directly or indirectly by the internal structure and related functions of ecosystems for human society as they continue to evolve and develop2.” Ecosystem Service Value (ESV), serving as a metric for appraising ecological environment quality, involves the utilization of economic metrics to gauge the benefits humans derive from ecosystems, thereby rendering these values commensurable across different regions3. Research on land use change encompasses the evaluation, analysis, and prediction of land use quantity, type structure, and spatiotemporal dynamics. Changes in land use influence the spatial distribution and extent of ecosystems, and indirectly impact the services and values that ecosystems provide4,5,6. Through extensive research on land use change, scholars have discovered a close correlation between land use change and the ecological environment.

Globally, methods for evaluating ESV are primarily categorized into monetary valuation methods and emergy analysis7. The monetary valuation method is one of the earliest and most widely adopted approaches for assessing ESV. It includes two main techniques: the unit area value equivalent factor method and the unit area service function pricing method. The unit area value equivalent factor method was initially developed by Costanza et al.8., who compiled a valuation table summarizing the per-unit area values of various ecosystem services across different ecosystems. This method estimates the total ESV of a region by integrating the area statistics of various ecosystems within the study area. Xie9 and colleagues later refined and adapted this method for broader applicability. The unit area service function pricing method is further divided into market-based valuation and non-market valuation approaches10. The market-based approach assesses ecosystem services with directly transactable values, such as those related to material production, information, and certain regulatory functions. In contrast, the non-market valuation approach applies techniques like replacement cost11 and hedonic pricing12 to estimate the value of ecosystem services that do not have direct market prices. Emergy analysis, introduced by Odum13 et al., measures the total usable energy consumed during the production of goods or services. This method calculates ESV through emergy conversion rates and emergy differentials. For instance, Chen14. applied emergy analysis to assess the sustainability of the socio-economic system in Qinghai Province from a donor perspective. At the regional level, international scholars have conducted extensive ESV research. Xie et al.15, building on Costanza’s framework and adapting it to China’s conditions, developed a value equivalent table for various terrestrial ecosystems. Due to its simplicity and reliability, this table has seen widespread adoption in China. In 2014, Costanza et al.16 updated the unit area value equivalent factors, which Fu17. and colleagues used to model land use changes in the Altay region under three scenarios from 2015 to 2035. Their analysis revealed the spatial heterogeneity and variability of ecosystem service interactions at both regional and grid scales across scenarios. Yoshida et al.18 employed the ecosystem coefficients proposed by Costanza and colleagues to study land use patterns and ecosystem types in northern Laos, finding a decline in ESV and highlighting the relative rigidity of total ESV in the region.

In general, Research on land use change and ESV, both domestically and internationally, primarily addresses changes in land types19,20,21,22, scales of land structures23,24,25, driving factors of land use26,27,28, long time series29,30,31,32, modifications in landscape patterns33,34,35, risk assessments of landscapes36,37,38,39, evaluations of ecological service values40,41,42,43, and advancements in methodologies for enhancing ecological service values44,45.The unit area value equivalent factor method is a widely utilized approach for evaluating ESV due to its maturity and comprehensiveness. This method has several advantages: it is straightforward to calculate, requires minimal data, and depends on easily accessible sources, making it ideal for large-scale statistical analyses or cross-regional comparisons. Additionally, it closely aligns with individuals’ willingness to pay, which facilitates acceptance by both parties in compensation schemes and enhances its practical application. Nevertheless, this method also has limitations, particularly its sensitivity to spatial heterogeneity. The service value per unit area of ecosystems can vary greatly due to regional differences in natural environments, often resulting in discrepancies between the estimated and actual values. This variation makes it difficult to accurately capture the intra-regional differences in ecosystem services. In terms of research subjects, there is a significant focus on natural areas such as forests and grasslands46,47,48, as well as ecologically vulnerable regions like coastal zones49 and nature reserves50,51,52,53,54,55, which are prone to human impacts. Conversely, research into cities and urban agglomerations, characterized by diverse human activities and complex land use patterns, remains insufficient.

The objectives and primary contributions of this study are as follows:

(1)This study aims to accurately assess the changes in ESV in Xi’an and evaluate the rationality of its land use structure by developing a quantitative approach for ESV evaluation at the administrative district level. Using long-term, continuous land use data from Xi’an and integrating methods such as land use dynamics analysis, land use transition matrix models, and the unit area value equivalent factor method, the study systematically investigates the evolution of land use patterns and the corresponding trends in ESV gains and losses. It also analyzes the spatial and temporal distribution characteristics of these changes. The objective is to provide scientific evidence and decision-making support for land resource management, urban ecological protection, and high-quality development in Xi’an as a national central city.

(2)To address spatial heterogeneity, which significantly affects the accuracy of the unit area value equivalent factor method, and to improve the precision of ESV assessment in the study area, this research modifies the ESV coefficients based on Xie Gaodi’s approach and adjusts the large-scale equivalent factors for terrestrial ecosystems in China to the city level by incorporating biomass factors specific to farmland ecosystems in Shaanxi Province. Given that variations in land use types and adjustment coefficients can influence ESV, establishing appropriate correction coefficients is crucial for accurately reflecting the real changes in ESV within the study area.

Materials and methods

Study area overview

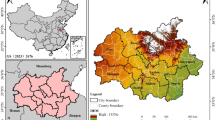

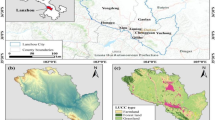

Xi’an is located in the center of the Guanzhong Plain, bordered by the Weihe River to the north and the Qinling Mountains to the south. It is recognized as one of China’s four major ancient capitals and a critical origin of Chinese culture and national identity. Additionally, Xi’an is known as the starting point of the Silk Road. Xi’an City spans from 107°40’ to 109°49’ East longitude and from 33°42’ to 34°45’ North latitude, encompassing a total land area of 10,182.06 km2. The terrain resembles a staircase, with higher altitudes in the south decreasing gradually toward the north. It is situated in a mild, temperate semi-humid continental monsoon zone, characterized by warm summers, cold winters, and alternating rainy and dry seasons. Recent rapid economic growth and increasing urbanization have led to significant changes in land use across Xi’an, significantly impacting its biological environment (Fig. 1).

Location of the study area. Note: The map was created by Arcgis 10.7 and the URL link is https://gme.youqun1.cn/soft/106402.html?bd_vid=11112968300404437655.

Data description

Various domestic and international research studies have shown that land use data can effectively describe urban land use and ecological changes. Xie Gao Di’s study findings in China are frequently utilized to assess ESV. Economic and social data can simultaneously show metropolitan areas’ economic development level and ecosystem services’ importance.

The land use statistics for Xi’an in 2000, 2010, 2015, and 2020 were acquired from the Resource and Environment Science Statistics Centre of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (website: http://www.resdc.cn). The land use data were obtained from the China Multi-period Land Use Remote Sensing Monitoring Data Set (CNLUCC). This dataset has been validated and cited in several previous studies56,57. The datasets were obtained from Landsat TM/ETM remote sensing pictures with a spatial resolution of 30 m for each time frame. Visual interpretation was utilized in dataset development through human-computer interaction.

Socio-economic statistics regarding the planted area, production, and price of essential crops were collected from the Shaanxi Provincial Statistical Yearbook, the National Compendium of Agricultural Product Costs and Benefits, and the Xi’an Municipal Statistical Yearbook. The datasets were mainly used to estimate ESV. All data was spatially organized into a 3 km×3 km grid of 3507 grid cells to improve study convenience. Various domestic and international research studies have shown that land use data can effectively describe urban land use and ecological changes. Xie Gao Di’s research results in China are often utilized through ESV, with economic and social data illustrating the economic growth level in urban agglomerations and the worth of ecosystem services (Table 1).

Research methodology

Land movement attitudes

The single dynamic attitude Kt and comprehensive dynamic attitude St are used to quantify the rate and quantity of change in a specific land use type or overall land use type over a certain period. A larger dynamic attitude indicates a faster rate of change in the land use type50. The formula is as follows:

Kt represents a single land use type, Ub and Ua are the areas of land use types at the end and beginning of a time period in the study area, T is the length of the time period in years, St is the combined land use attitude during the time period of T, Sij is the sum of the areas of land use type i shifted to the area of land use types other than i during the time period of T, and Si is the total area of the land use type i at the beginning of the study area.

Land-use transfer matrix

The land use transfer matrix quantitatively describes the process of converting and transferring land between different land use elements over a period of time. It provides a full reflection of the direction of land use conversion within a specified time frame55.

Equation (3) defines S as the land use area, n as the number of land use types, i and j as the initial and final land use types, and Sij as the area converted from type i to type j throughout the research period. The benefit of this method is its ability to accurately and intuitively depict the structural features of land use change in the research area. It can then analyze the spatial direction of change for each land type caused by human activities. A higher value indicates a more significant change, while a lower value suggests a less pronounced change.

Estimating the value of ecosystem services

Calculation of the value of ecosystem services per unit area of farmland

This study utilizes the “Equivalent Factor Method of Unit Area Value” introduced by Xie Gao Di et al.43. to calculate the Effective Sample Volume in Xi’an City. The average grain yield in Xi’an from 2000 to 2020 was 4460 kg/hm2, while the national average grain yield was 4982.00 kg/hm2. The national average purchase price of wheat, corn, and rice from 2000 to 2020 was calculated as the basic unit price data, according to the Xi’an Statistical Yearbook and the National Compendium of Cost and Benefit Information of Agricultural Products. The national average purchase price of wheat, maize, and rice from 2000 to 2020 was used as the base unit price data to calculate the “ESV for one standard equivalent factor (Ea)” for various periods. This value was adjusted by the willingness-to-pay coefficient. The formula for Ea is as follows.

Where Eat represents the value of ecosystem services for one standard equivalent factor in year t; Rt is the willingness-to-pay coefficient in year t, determined with respect to Lin Dong, etc58. ; i indicates the type of crop (the primary food crops in Xi’an city: wheat, maize, and rice); m is the planted area of the food crop in year t (hm2), p is the price of the food crop in year t (yuan/kg), and q is the yield of the food crop in year t (kg/hm2). M represents the combined planted area of the three food crops in year t (hm2); 1/7 denotes the economic value generated by natural ecosystems independently, equivalent to 1/7 of the economic value of food production services from the current unit amount of cultivated land.

ESV regional variance coefficient correction

Based on the nationwide ESV value equivalent table by Xie Gao Di et al., adjustments were made for Xi’an City by referencing the research findings of Zhao Xianchao et al. and Liu Hai et al.59,60. The ESV coefficients were corrected using the biomass correction coefficient in Shaanxi Province (0.51)61and the ratio of grain unit yield in Xi’an City compared to the national average, resulting in the ESV value per unit area for Xi’an City. Analyzed the ecosystem services’ value per unit area in Xi’an and recorded the results in Table 1. The computation formula was as stated (Table 2).

Z is the correction coefficient for regional disparities in Xi’an; QXi’anand QChina are the average grain yields in Xi’an and the entire country, respectively; Er is the adjusted ESV coefficient. The ecosystem service value and its intensity were determined in the following manner.

Where: ESV represents ecosystem service value; represents ecosystem service value intensity; Aij represents the land area of category i in grid j. S represents the grid area, while n represents the land use category.^.

Modelling the flow of value gains and losses from ecosystem services

The ESV gain/loss model, which is based on the land use transfer matrix, considers quantitative changes in ESV and spatial and temporal transfer trends in the study area62. It shows the sources and directions of ESV gain/loss due to spatial shifts in land use types over different time periods. The paper calculates the land use transfer matrix using land use data and determines the ESV gain/loss resulting from shifts in land use types in the studied area.The equation for determining the ESV flow gain/loss is as follows:

Pij represents the change in ecological service value when land use type i is converted to land use type j. If Pij is positive, the service value improves; if Pij is negative, the value is lost. Vi and Vj represent the ESV coefficients of land use types i and j, respectively, whereas Sij denotes the area of land use type changed from i to j. The research framework was shown in Fig. 2.

Results and analyses

Land use conversion analysis

Xi’an’s land use data for 2000, 2010, 2015, and 2020 were classified into six categories based on the National Standard for Classification of Current Land Use Situations (GB/T21010-2007) and Xi’an’s specific land use characteristics. These categories include cultivated land, forest land, grassland, water, construction land, and unused land. ArcGIS was utilized to analyze Xi’an’s spatial and temporal land use patterns from 2000 to 2020. The land area of each land use type in Xi’an and its percentage of the total area are determined using vectorization and type subsumption (Table 3). The single land use dynamics and comprehensive land use dynamics of Xi’an for each year are then calculated based on Eq. (1) (Table 3).

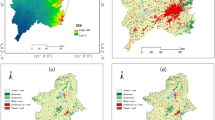

The land use structure of Xi’an City from 2000 to 2020, as shown in Table 2, indicates that cultivated land and forest land dominated the land types during this period. cultivated land decreased by 538.37 km2, shifting from 42.04 to 36.7% of the total area. Forest land remained relatively stable due to national environmental protection policies and decreased by 28.13 km2. The forest land area has remained relatively stable recently due to national policies protecting the ecological and Qinling environments. The grassland area has fluctuated, expanding from 2000 to 2010 and decreasing from 2010 to 2020. The water area has mainly been influenced by wetland evaporation and human social and economic activities and has fluctuated, decreasing from 2000 to 2020. The fluctuating change in water area is primarily influenced by wetland evaporation and human social and economic activities. Over 20 years, the construction land area has increased by 540.8 km2, representing the most significant change as its proportion of the total study area has grown from 8.49 to 13.85%. When forest land and cultivated land are converted into construction land, the expansion of the construction area takes up a significant portion of cultivated land, extending into forested and cultivated land (Figs. 3 and 4).

The single land use momentum attitude is a metric used to quantify the rate of land transformation. A higher value indicates a quicker pace of change. Table 2 displays significant variations in the changes of different land use types across three periods. Construction land consistently exhibits the most substantial change in a single dynamic attitude, with a faster rate of change. Conversely, unused land has a lesser impact overall due to its smaller area. Between 2000 and 2010, the most significant fluctuations in land use changes occurred in construction land, grassland, and water. Changes in cultivated, forest, and unused land were slower during this period. From 2010 to 2015, all land use areas, except for cultivated land and construction land, experienced an increase. Between 2010 and 2015, all land uses decreased except for cultivated land and construction land, which increased. The area of cultivated land only increased by 0.05%, showing a relatively stable trend. From 2015 to 2020, watersheds experienced the fastest rate of change, while cultivated land, grassland, and unused land areas decreased.

The synchronized dynamic attitude of the three time intervals aligns with the general development trend of Xi’an City. Land use changes were more pronounced during 2000–2010, with an integrated land use degree of 0.71. This aligns with the rapid development phase of the country before and after 2005. Subsequently, land use changes stabilized during 2010–2015 but increased again during 2015–2020, with an integrated land use motivation degree of 0.76%. This is significantly higher than the motivation degree of 0.41% during 2010–2015, indicating a greater intensity of land use changes in Xi’an after 2015.

Analysis of land-use transfer characteristics

The analysis of the 2000–2020 land use transfer matrix and spatial distribution map of Xi’an reveals varying interconversions between land use types during this period, displaying distinct characteristics across different time frames and land use categories. The total area altered from 2000 to 2020 is 3211.626 km2, primarily consisting of cultivated land, forest land, and building land. The land area converted between 2010 and 2015 was the highest, totalling 1,216.262 km2. In contrast, the land area converted between 2005 and 2010 was the smallest, totalling 780.838 km2, and only two-thirds of the area converted between 2010 and 2015. Two-thirds of the area was converted between 2010 and 2015 (Fig. 5).

The chart illustrates the transformation of six land use types in Xi’an from 2000 to 2020 (Tables 4, 5 and 6). It shows that construction land expansion is notably more significant than other land use types, with cultivated land and forest land being primary sources. The expansion rate demonstrates a rising trend before 2015, followed by a gradual decline after 2015. Between 2000 and 2010, the city of Xi’an experienced minimal changes in its structure overall. However, there was a noticeable construction land expansion on the outskirts of the urban built-up area. From 2010 to 2015, Xi’an’s metropolitan region underwent significant changes, transitioning into a rapid growth phase. The city’s southern section saw significant advancements with the creation of the South Third Ring Road, the South Beltway Highway, and Chang’an District. Between 2015 and 2020, the government work report emphasized the establishment of “Great Xi’an,” enhancing the merging of Xixian and Xian. The focus shifted towards developing the Xixian and Xian areas, resulting in a slower growth rate for the Xi’an built-up area. This change transitioned from incremental construction to a stock development mode, particularly evident in the development of local plots within the city. Xi’an’s urban growth is transitioning from incremental construction to stock development, primarily seen in the renewal of local land plots and the renovation of ancient areas.

Analysis of the spatial and temporal evolution of the value of ecosystem services

The table of changes in ESV of different land types in Xi’an (Fig. 6) shows that the ESV of Xi’an has increased from 617.6 million yuan to 1556.4 million yuan. This increase is due to more than just the focus on ecological environmental protection in recent years in Xi’an. From the point of view of each land use type, forest land and water are the main contributors to ESV, in which the contribution rate of cultivated land and forest land shows a decreasing trend from 2000 to 2015, and the contribution rate of cultivated land and forest land shows a slight increase in 2020, insisting on the fluctuating contribution rate of ecological environment under the policy orientation of harmonious coexistence between human and nature; among the remaining land use types, the contribution rate of grassland in 2015 peaks and then declines, the ESV and contribution rate of waters fluctuates more, and the ecological compensation capacity of waters fluctuates with different meteorological conditions every year, the ESV and contribution rate of construction land increases year by year, which is due to the expansion of construction land from 2000 to 2020, and part of the cultivated land and forest land is converted into construction land, and the ESV and contribution rate of the unutilised land remain more stable, the changes are not significant (Figs. 7 and 8).

The fishing net tool was used to visually represent ESV’s spatial distribution and features in urban agglomerations. The intensity of ESV in Xi’an City from 2000 to 2020 was mapped onto a 3 km×3 km grid. The ESV was divided into five intervals using the natural breakpoint method: low-value region, second-low-value area, intermediate-value area, and second-high-value area. Between 2000 and 2020, the ESV in Xi’an City remained spatially consistent, with a pattern of being higher in the south than in the north. The ESV north of the Qinling Mountains had more significant changes, with the ESV shifting to high-value in the low-value zone. The ESV values north of the Qinling Mountains exhibit significant variation, leading to a rise in grids where the second-lowest values transition to the middle value. The regions with high ESV values are concentrated in the southern areas of the Qinling Mountains, characterized by dense forests and proximity to the Weihe, Bahe, and Chanhe Rivers. Other areas radiate outward from these high-value regions, with the middle-value areas primarily located in the cultivated land of the Guanzhong Plain to the north of the Qinling Mountains. The second-low-value regions are found on the outskirts of the built-up areas of the main urban area of Xi’an, while the low-value regions are mainly within the built-up areas of the main urban area of Xi’an. The low-value area is primarily located within the urbanized region of the central metropolis of Xi’an (Fig. 9).

This study quantitatively analyzes the influence of different types of land use changes on the value of ecosystem services by examining the flow of ESV among different land uses. From 2000 to 2020, Xi’an City experienced a positive net growth in ecological service value. From 2000 to 2010, there was a total gain of 599.0 million yuan, with forested land, cultivated land, and grass land contributing significantly. Between 2010 and 2015, the gain was RMB 162.1 million, primarily driven by forest land, cultivated land, and construction land regarding ESV. From 2015 to 2020, the gain amounted to RMB 331.1 million, with forest land, cropland, and construction land playing a significant role. Since 2010, the rise in the worth of ecosystem services in Xi’an has been influenced by the expansion of the total construction area, alterations in the value of forest land and cultivated land, and the frequent conversion of grassland, cultivated land, forest land, and construction land, resulting in fluctuations in the value of ecosystem services (Fig. 10).

Discussion

Spatial and temporal changes in the value of land use and ecosystem services

The findings of this study on land utilization in Xi’an closely align with those of other scholars. Changes in land utilization are evident in the expanded development areas and the reduced extents of cultivated and forest lands63. This research typically focuses on land use changes at a macroscopic time scale. Further analysis at a micro time scale is needed, which impedes the investigation of the relationship between land use changes and urban growth55,64.

From 2000 to 2020, Xi’an City’s ESV consistently increased. Geographically, the pattern was “higher in the south than in the north.” Stability remained relatively constant, with high ESV areas in the southern Qinling Mountains, particularly in larger forested areas, and near the Weihe, Bahe, and Chanhe Rivers. This finding partially aligns with those of Yang65 and Zhang66, who observed similar spatial distributions of high ESV areas in regions dominated by forested landscapes. However, differences exist in the specific ESV growth trends, which can be attributed to variations in ESV calculation methods and local land use policies. This finding contrasts with the studies of Zhu Linna62 and Zhang Hui67 Following comprehensive analysis, we identified differences in ESV calculation methods as the primary factor for the discrepancy in study results. For instance, while Zhu and Zhang applied standard grid-based calculations, this study incorporated region-specific modifications, making the results more relevant to Xi’an’s unique ecological and economic conditions. This study has both similarities and differences compared to previous research. In terms of similarities, all studies use long-term time series data to analyze the spatial and temporal changes in ESV. However, in terms of differences, the methods for evaluating ESV vary. The methods used in the previous two studies simply applied the grid method to assess ESV changes in Xi’an. In contrast, this study not only modifies the ESV coefficients based on Xie Gaodi’s unit area value equivalent factor method but also incorporates biomass factors specific to farmland ecosystems in Shaanxi Province to adjust the large-scale equivalent factors to the municipal scale. This approach is consistent with findings by Li68, who emphasized the importance of localizing ESV coefficients to improve assessment accuracy in specific regions.This approach enhances the accuracy of the unit area value equivalent factor method, providing a more scientific and accurate representation of ESV in the study area.

ESV assessment methods and accuracy correction

Several techniques assess ESV, including the equivalent factor approach, shadow pricing, substitute cost, material quality conversion, energy value conversion, NPP, and modeling methods. The equivalent factor method is widely used in ESV studies to assess the ESV of all land types within a region, unlike other methods focused on specific land uses such as forests, grasslands, and water bodies69,70,71. The study adopted a method based on the unit area value equivalent factor to facilitate data collection, standardize evaluation methods and parameters, and enable visual comparisons. This study improved the accuracy of assessing ecological service values by adjusting the ESV coefficients with the Xie Gao Di unit-area value equivalent factor method. Additionally, it adjusted the large-scale equivalent factor from the Chinese terrestrial to the geographical scale by incorporating the biomass factor of agricultural ecosystems in Shaanxi Province. Variations in land use types and correction factors affect the valuation of ecological services. Establishing an appropriate correction factor is essential to accurately represent the actual fluctuations in ecological service values in the research region.

Research limitations and future prospects

This study presents certain limitations in the assessment of ecosystem service value (ESV). First, the spatial heterogeneity inherent in the unit area value equivalent factor method means that our correction factors may not fully account for regional variations, potentially impacting the precision of our assessment. Second, the study primarily relies on land use data from Xi’an, which may lack the temporal and spatial resolution needed to accurately capture changes at finer scales. Moreover, although the study analyzes the effects of land use changes on ESV, it does not explore the specific drivers and underlying mechanisms of these changes, limiting the understanding of the complexity behind ESV dynamics.

Future research will aim to address these limitations. We plan to incorporate more detailed remote sensing data and high-resolution land use data to enhance the spatial accuracy of our assessment. In addition, we will apply spatial statistical techniques such as Geodetector and Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) to comprehensively investigate the multidimensional drivers of ESV and their spatial heterogeneity, with the goal of revealing complex spatial patterns and variation mechanisms. Furthermore, to validate the correction factors applied in this study, we will expand the research scope to other regions and ecosystems to test the robustness and broader applicability of the method. These efforts aim to establish a more comprehensive and reliable theoretical foundation for the evaluation and application of ESV.

Conclusion

This study examined the spatiotemporal dynamics of land use and ecosystem service value (ESV) in Xi’an from 2000 to 2020. By analyzing changes in land use types, conversion patterns, and their implications for ecosystem services, the research provides insights into the underlying trends and regional characteristics of land use transitions. The findings contribute to understanding how urbanization and ecological processes interact in a rapidly developing city.

-

(1)

Land use types in Xi’an varied from 2000 to 2020. From 2000 to 2020, cultivated and forest lands dominated land use in Xi’an. Construction land expanded significantly, largely at the expense of cultivated and forested areas. Land use changes were most pronounced from 2000 to 2010, with a comprehensive land use index of 0.71. After 2015, these changes intensified, suggesting a critical period for future research.

-

(2)

The conversion of agricultural, forest, and construction land is apparent in Xi’an. The city experienced a total land conversion of 3211.626 km2 over two decades, primarily involving cultivated, forest, and construction lands. Construction land expansion, mainly sourced from cultivated and forest lands, peaked before 2015 and then slowed.

-

((3)

ESV in Xi’an increased from 617.6 million yuan to 1556.4 million. Forest and water bodies consistently contributed the most to ESV, while contribution rates from cultivated and forest lands decreased until 2015 and rebounded slightly in 2020. Grassland contribution rates peaked in 2015, and construction land ESV increased steadily. Spatially, ESV was higher in southern Xi’an than in the north, with notable variations north of the Qinling Mountains over the past two decades. High ESV areas were concentrated south of the Qinling Mountains, especially in dense forests near the Weihe, Bahe, and Chanhe Rivers. Intermediate values were observed in the southern Qinling Mountains, with the highest ESV on the Guanzhong Plain farmland plateau and the lowest in urban outskirts and built-up areas.

-

(4)

Between 2000 and 2020, Xi’an City experienced a net increase in the value of ecosystem services. ESV rose significantly, with net gains of 599.0 million yuan from 2000 to 2010, 162.1 million yuan from 2010 to 2015, and 331.1 million yuan from 2015 to 2020. Forest, cultivated, and construction lands were the main contributors to this growth.

Data availability

Data Availability Statement: All land use statistics used in the study are available for free down load through (http://www.resdc.cn/), Socio-economic statistics regarding the planted area, production, and price of important crops were collected from(http://tjj.shaanxi.gov.cn/),(https://www.stats.gov.cn/) and (http://tjj.xa.gov.cn/).

References

Arcidiacono, A., Ronchi, S. & Salata, S. Ecosystem Services assessment using InVEST as a tool to support decision making process: critical issues and opportunities.Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA : 15th International Conference, Banff, AB, Canada, June 22–25, 2015, Proceedings, Part IV 15 35–49 (Springer). (2015).

Niu, H., An, R., Xiao, D., Liu, M. & Zhao, X. Estimation of ecosystem services value at a basin scale based on modified equivalent coefficient: A case study of the Yellow River Basin (Henan Section), China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19, 16648. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416648 (2022).

La Notte, A. et al. Ecosystem services classification: A systems ecology perspective of the cascade framework. Ecol. Ind. 74, 392–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.11.030 (2017).

Benito Garzón, M., de Dios, S., Sainz Ollero, H. & R. & Effects of climate change on the distribution of Iberian tree species. Appl. Veg. Sci. 11, 169–178. https://doi.org/10.3170/2008-7-18348 (2008).

Davison, C. W., Rahbek, C. & Morueta-Holme, N. Land‐use change and biodiversity: Challenges for assembling evidence on the greatest threat to nature. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 5414–5429. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15846 (2021).

Vallecillo, S., Brotons, L. & Thuiller, W. Dangers of predicting bird species distributions in response to land-cover changes. Ecol. Appl. 19, 538–549. https://doi.org/10.1890/08-0348.1 (2009).

Liu, C. X. et al. Research progress of ecosystem service valuation. J. Green Sci. Technol. 273–280. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.16663/j.cnki.lskj (2024).

Costanza, R. et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387, 253–260 (1997).

Xie, G. et al. Improvement of the evaluation method for ecosystem service value based on per unit area. J. Nat. Resour. 30, 273–280. https://doi.org/10.16663/j.cnki.lskj.2024.03.010 (2015).

Yang, G. et al. Review of foreign opinions on evaluation of ecosyste mservices 205–212 (ACTA ECOLOGICA SINICA, 2006).

Rapport, D. et al. Evaluating landscape health: integrating societal goals and biophysical process. J. Environ. Manag. 53, 1–15 (1998).

Chee, Y. E. An ecological perspective on the valuation of ecosystem services. Biol. Conserv. 120, 549–565 (2004).

Odum, H. T. Self-organization, transformity, and information. Science 242, 1132–1139 (1988).

Chen, W. et al. An emergy accounting based regional sustainability evaluation: A case of Qinghai in China. Ecol. Indic. 88, 152–160 (2018).

Xie, G. et al. Progress in evaluating the global ecosystemservices. Resour. Sci. 5–9. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=IylmbgxpP4SnbuBz- (2001).

Costanza, R. et al. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Glob. Environ. Change 26, 152–158 (2014).

Fu, Q. et al. Scenario analysis of ecosystem service changes and interactions in a mountain-oasis-desert system: A case study in Altay Prefecture, China. Sci. Rep. 8, 12939 (2018).

Yoshida, A., Chanhda, H., Ye, Y. M. & Liang, Y. R. Ecosystem service values and land use change in the opium poppy cultivation region in Northern Part of Lao PDR. J. Environ. Sci.. 30, 56–61 (2010).

Barton, J. & Pretty, J. What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 3947–3955. https://doi.org/10.1021/es903183r (2010).

Hu, Z., Yang, X., Yang, J., Yuan, J. & Zhang, Z. Linking landscape pattern, ecosystem service value, and human well-being in Xishuangbanna, southwest China: Insights from a coupling coordination model. Glob.Ecol. Conserv. 27, e01583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01583 (2021).

Rodríguez, J. P. et al. Trade-offs across space, time, and ecosystem services. Ecol. Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01667-110128 (2006).

Zhuang, D. & Liu, J. Modeling of regional differentiation of land-use degree in China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 7, 302–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11769-997-0002-4 (1997).

Jayawardana, J., Gunawardana, W., Udayakumara, E. & Westbrooke, M. Land use impacts on river health of Uma Oya, Sri Lanka: implications of spatial scales. Environ. Monit. Assess. 189, 1–23 (2017).

Salvati, L., Zambon, I., Chelli, F. M. & Serra, P. Do spatial patterns of urbanization and land consumption reflect different socioeconomic contexts in Europe? Sci. Total Environ. 625, 722–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.341 (2018).

Wei, S., Pan, J. & Liu, X. Landscape ecological safety assessment and landscape pattern optimization in arid inland river basin: Take Ganzhou District as an example. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. https://doi.org/10.1080/10807039.2018.1536521 (2018).

Adams, V. M., Pressey, R. L. & Álvarez-Romero, J. G. Using optimal land-use scenarios to assess trade-offs between conservation, development, and social values. PLoS ONE. 11, e0158350. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158350 (2016).

Cheng, L. L., Tian, C. & Yin, T. T. Identifying driving factors of urban land expansion using Google Earth Engine and machine-learning approaches in Mentougou District, China. Sci. Rep. 12, 16248. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20478-z (2022).

Kim, Y., Newman, G. & Güneralp, B. A review of driving factors, scenarios, and topics in urban land change models. Land 9, 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9080246 (2020).

Akhtar, N. & Tsuyuzaki, S. Effects of disturbances on the spatiotemporal patterns and dynamics of coastal wetland vegetation. Ecol. Indic.. 166, 112430 (2024).

Huang, M. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics and forecasting of ecological security pattern under the consideration of protecting habitat: A case study of the Poyang Lake ecoregion. Int. J. Digit. Earth 17, 2376277 (2024).

Luan, G. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of ecosystem supply service intensity in China: Patterns, drivers, and implications for sustainable development. J. Environ. Mange. 367, 122042 (2024).

Yao, X., Zhou, L., Wu, T., Yang, X. & Ren, M. J. Ecosystem services in National Park of Hainan Tropical Rainforest of China: Spatiotemporal dynamics and conservation implications. Nat. Conserv. 80, 126649 (2024).

Abdullah, S. A. & Nakagoshi, N. Changes in landscape spatial pattern in the highly developing state of Selangor, peninsular Malaysia. Landsc. Urban Plann. 77, 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.03.003 (2006).

Mirghaed, F. A. & Souri, B. Spatial analysis of soil quality through landscape patterns in the Shoor River Basin, Southwestern Iran. Catena 211, 106028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106028 (2022).

Wang, Q. et al. Landscape pattern evolution and ecological risk assessment of the Yellow River Basin based on optimal scale. Ecol. Ind. 158, 111381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.111381 (2024).

Funk, R., Völker, L. & Deumlich, D. Landscape structure model based estimation of the wind erosion risk in Brandenburg. Ger. Aeolian Res. 62, 100878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeolia.2023.100878 (2023).

Guo, H., Cai, Y., Li, B., Wan, H. & Yang, Z. An improved approach for evaluating landscape ecological risks and exploring its coupling coordination with ecosystem services. J. Environ. Manage. 348, 119277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119277 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Optimization of landscape pattern in China Luojiang Xiaoxi basin based on landscape ecological risk assessment. Ecol. Indic. 146, 109887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.109887 (2023).

Xu, M. & Matsushima, H. Multi-dimensional landscape ecological risk assessment and its drivers in coastal areas. Sci. Total Environ. 908, 168183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168183 (2024).

Obst, C., Hein, L. & Edens, B. National accounting and the valuation of ecosystem assets and their services. Environ. Resour. Econ. 64, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-015-9921-1 (2016).

Peng, Y., Welden, N. & Renaud, F. G. A framework for integrating ecosystem services indicators into vulnerability and risk assessments of deltaic social-ecological systems. J. Environ. Manage. 326, 116682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116682 (2023).

Smith, L. M. et al. Methods for a composite ecological suitability measure to inform cumulative restoration assessments in Gulf of Mexico estuaries. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110896 (2023).

Xie, G., Zhang, C., Zhang, L., Chen, W. & Li, S. Improvement of ecosystem service valorization method based on unit area value equivalent factor. J. Nat. Resour. 30, 1243–1254 (2015).

Huang, J., Yang, H., He, W. & Li, Y. Ecological service value tradeoffs: An ecological water replenishment model for the jilin momoge national nature reserve, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 3263. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063263 (2022).

Nazer, N., Chithra, K. & Bimal, P. Framework for the application of ecosystem services based urban ecological carrying capacity assessment in the urban decision-making process. Environ. Chall. 13, 100745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2023.100745 (2023).

Bao, T. & Xi, G. Impact of grassland storage balance management policies on ecological vulnerability: Evidence from ecological vulnerability assessments in the Selinco region of China. J. Clean. Prod. 426, 139178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139178 (2023).

Kaur, R., Joshi, O. & Will, R. E. The ecological and economic determinants of eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) encroachment in grassland and forested ecosystems: a case study from Oklahoma. J. Environ. Manage. 254, 109815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109815 (2020).

Redin, C. G. et al. Soil-landscape-vegetation relationships in grassland-forest boundaries, and possible applications in ecological restoration. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 132, 104684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2023.104684 (2023).

Zhou, B., Xu, J., Yu, H. & Wang, L. Comprehensive assessment of ecological risks of Island destinations—A case of Mount Putuo Island, China. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110783 (2023).

Fu, J. X., Cao, G. C. & Guo, W. J. Land use change and its driving force on the southern slope of Qilian Mountains from 1980 to 2018. Ying Yong Sheng tai xue bao. Ying Yong Sheng tai xue bao J. Appl. Ecol. 31, 2699–2709 (2020).

Ikhumhen, H. O. et al. Coastal waterbird eco-habitat stability assessment in Zhangjiangkou Mangrove National Nature Reserve Based on habitat function-coordination coupling. Ecol. Indic 72, 101871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2022.101871 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. p How do local people value ecosystem service benefits received from conservation programs? Evidence from nature reserves on the Hengduan Mountains. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01979 (2022).

Xia, H., Li, H. & Prishchepov, A. V. Assessing forest conservation outcomes of a nature reserve in a subtropical forest ecosystem: effectiveness, spillover effects, and insights for spatial conservation prioritization. Biol. Conserv. 285, 110254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.110254 (2023).

Zhang, P., Li, X. & Yu, Y. Relationship between ecosystem services and farmers’ well-being in the Yellow River Wetland Nature Reserve of China. Ecol. Ind. 146, 109810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109810 (2023).

Ni, X., Jie, X. & Pingyun, W. Analysis of Land Use Change and Driving Forces Based on Remote Sensing Images 41–44 (Urban Geotechnical Investigation and Surveying, 2021).

Dong, G., Ge, Y., Jia, H., Sun, C. & Pan, S. J. L. Land use multi-suitability, land resource scarcity and diversity of human needs: A new framework for land use conflict identification. Land 10, 1003 (2021).

Yang, F. et al. Spatiotemporal evolution of production–living–ecological land and its eco-environmental response in China’s coastal zone. J. Environ. Manage. 15, 3039 (2023).

Dong, L., Huiling, M., Zhengchao, R. & Yuanheng, L. Dynamic analysis of ecosystem service value based on land use/cover change in Lanzhou. City Ecol. Sci. 35, 134–142. https://doi.org/10.14108/j.cnki.1008-8873.2016.02.021 (2016).

Liu, H., Yin, J., Lin, M. & Chen, X. Sustainable development evaluation of the Poyang Lake Basin based on ecological service value and structure analysis. Acta Ecol. Sin. 37, 7–12. https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb201510102045 (2017).

Xianchao, Z., Yidou, T. & Xiaoxiang, Z. Spatio-temporal relationship between land use carbon emissions and ecosystem service value in Changzhutan urban agglomeration. J. Soil Water Conserv. 37, 215–225. https://doi.org/10.13870/j.cnki.stbcxb.2023.05.026 (2023).

Gao-Di, X., Yu, X., Lin, Z. & Chun-Xia, L. Study on ecosystem services value of food production in China. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 13, 10–13 (2005).

Linna, Z., Mudan, Z., Yi, F. & Jian, W. The space-time relationship between the ecosystem service value and the human activity intensity in Xi′an Metropolitan Area. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. https://doi.org/10.19741/j.issn.1673-4831.2022.1078

Yuxia, B. A study on land use change and ecological security patterns in Xi’an (2023).

Xinping, L. et al. Spatialand temporal shift in land use structureand and spatio-temporal variation in ecosystem services value in Henan Province. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 54, 138–150. https://doi.org/10.13928/j.cnki.wrahe.2023.01.013 (2023).

Yang, J., Xie, B. & Zhang, D. J. S. R. Spatial–temporal evolution of ESV and its response to land use change in the Yellow River Basin, China. J. Environ. Manage. 12, 13103 (2022).

Zhang, B., Wang, Y., Li, J. & Zheng, L. J. L. Degradation or Restoration? The temporal-spatial evolution of ecosystem services and its determinants in the Yellow River Basin, China. Land 11, 863 (2022).

Hui, Z. et al. Spatiotemporal evolution and association analysis of ecosystem service value and ecological risk in Xi’an. Environ. Ecol. 37–44. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=IylmbgxpP4Q2Vg- (2024).

Li, F. et al. A comparative analysis of ecosystem service valuation methods: Taking Beijing, China as a case. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110872 (2023).

Peiqing, L. et al. Dynamic evaluation of grassland ecosystem services in Xilingol League. Acta Ecol. Sin. 39, 3837–3849. https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb201811182502 (2019).

Qiang, W., Yuanying, P., Hengyun, M., Heping, Z. & Yiru, L. Research on the value of forest ecosystem services and compensation in a Pinus massoniana forest. Acta Ecol. Sin. 39, 117–130. https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb201809202052 (2019).

Wei, Y., Yuwan, J., Lixin, S., Tao, S. & Dongdong, S. Determining the intensity of the trade-offs among ecosystem services based on production-possibility frontiers:Model development and a case study. J. Nat. Resour. 34, 2516–2528. https://doi.org/10.31497/zrzyxb.20191203 (2019).

Funding

This study was supported by Xi ‘an social science planning Fund (Grant No.24QL47), Scientific Research Program Funded by Education Department of Shaanxi Provincial Government (Grant No.22JK0488), The Innovation Team of Eurasia University of Xi’an Eurasia University (Grant No. 2021XJTD01),and Scientific Research Platform of Eurasia University (Grant No. 2022XJZK04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, L.H. and Y.L.; methodology, L.H. and Z.G.; software, L.H.;validation, L.H., Y.L. and Z.D.; formal analysis, L.H. and L.G.; investigation, L.H. and F.F.; resources, L.C. , J.Z.and Z.D.; data curation, Y.L.,and F.F.; writing—original draft preparation, L.H.; writing—review and editing, L.H. and Z.G.; visualization, L.H. and L.G.; supervision, F.F. and Z.D.; project administration, Z.G. and L.C.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors haveread and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, L., Li, Y., Ge, Z. et al. Study on the spatial and temporal evolution of ecosystem service value based on land use change in Xi’an City. Sci Rep 15, 66 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83257-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83257-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Exploring the threshold of human activity impact on urban ecosystem service value: a case study of Hefei, China

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Spatial–temporal distribution of farmland occupation and compensation and its impact on ecological service value in China from 1990 to 2021

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A novel integrated framework for long-term assessment of ecosystem service degradation and restoration prioritization in a semi-arid rift valley landscape

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2025)

-

DSKN: Deep Spiking Kronecker Network for leaf type classification and multi-class leaf disease detection in internet of things based sustainable agriculture

Evolutionary Intelligence (2025)