Abstract

To investigate the sleep quality of incoming college freshmen who have completed college entrance exams but have not yet entered college, to identify associated factors, and the mediating role of siesta characteristics on the relationship between siesta duration and sleep quality. This study included 6,519 incoming freshmen from two colleges in Xuzhou city, China. Weighted multiple linear regression (MLR) and binary logistic regression (BLR) were employed to investigate the factors associated with sleep quality. Mediation analysis was conducted to examine the influence of siesta characteristics on sleep quality and siesta duration. Stratified analysis was conducted based on gender and college level to examine the correlation between sleep quality and siesta durations (1–29 min, 30–50 min, ≥ 60 min). Both regression models found that longer siesta duration was a risk factor for poor sleep quality. Mediation analysis demonstrated that sleep position, the interval between lunch and the siesta, and the subjective rating of sleepiness 30 min after the siesta mediated this relationship. Male students with 30–59 min siestas, junior college freshmen with 1–29 min siestas, and undergraduate freshmen with ≥ 60 min siestas exhibited an increased risk of poor sleep quality compared to their counterparts without siestas. Furthermore, lifestyle behaviors and physical activity were also found to impact sleep quality. Longer siesta duration has been identified as a risk factor for sleep quality, especially in incoming undergraduate and male students. Some siesta characteristics mediate the relationship between them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In China, around 8 million individuals undergo the rigorous academic challenge of the college entrance examination annually1. Following the examination, incoming college freshmen are afforded a distinctive transitional phase preceding the start of their academic journey. This period enables them not only to psychologically detach from academic stress and relax but also grants them ample opportunity to participate in social activities and nurture personal interests. Moreover, it presents an opportune time for adjusting and optimizing their sleep patterns. However, despite the alleviation of academic stress, some college freshmen still experience challenges with poor sleep quality.

Sleep plays a vital role in maintaining college students’ overall health and well-being2. Poor sleep quality has been associated with various physiological health issues: coronary heart disease, metabolic syndrome, hypertension2, and mental health issues: anxiety3, depression4. It is of great importance to understand the risk factors affecting sleep quality.

Previous literature has identified a multitude of risk factors associated with sleep quality among students, including lifestyle habits (smoking, drinking, caffeine use), mental health (depression, anxiety), and social factors (academic performance, sleep attitudes)5. However, there remains a dearth of research investigating the relationship between siesta and sleep quality among incoming college freshmen. In Chinese culture, siesta is deeply ingrained in daily routines. It is worth noting that the effects of siesta can vary depending on the duration, frequency, and individual differences6. While it is well established that siesta enhance cognitive abilities and well-being7,8, for adolescents who are often subjected to chronic sleep restriction, siesta may provide short-term benefits but can also lead to delayed bedtimes, contributing to a vicious cycle that further restricts sleep9,10. Leong et.al pointed that adolescents who had siestas more frequently, longer and closer to the beginning of the evening, can adversely impact their nocturnal sleep11. Similar findings have been reported in studies conducted with high school students in Brazil12. Such behaviors may even persist into their post-high school years during holiday periods.

It is essential to point out that simply having a longer sleep duration does not necessarily indicate better sleep quality. For middle-aged and elderly individuals, prolonged siesta durations serve as risk factors for diseases such as hypertension13, obesity6, cardiovascular disease14 and stroke15. Considering the bidirectional influence of siesta, it is crucial to conduct further research targeting different population groups to investigate the impact of siesta on sleep quality. Furthermore, some researchers have revealed factors related to siesta, such as the sleeping location and position, which may mediate the relationship between siesta and certain health outcomes6.

When conducting correlation research, it is noteworthy that different models may produce different results for the same independent and dependent variables. Furthermore, the same model with different processing methods may provide different outcomes. In ordered to obtain more robust results, it is necessary to employ standardized regression models in research. In the present study, different regression models were used to explore the associated factors, and each model underwent rigorous regression diagnostics. Regression diagnostics were often neglected when others used regression models. However, it ensures a more accurate estimation of parameters and P-values, thereby enhancing the overall quality of the analysis and reducing results bias.

This study aims to shed light on the factors that affect sleep quality among incoming college freshmen in Jiangsu Province, China while exploring the relationship between sleep quality and siesta duration. The study posits several hypotheses: (1) longer siesta duration is associated with poorer sleep quality; (2) some siesta characteristics may partially mediate the relationship between siesta duration and sleep quality; and (3) differences in college level and gender may influence the relationship. Through these analyses, the study not only fills a gap in the existing literature but also provides valuable insights for developing targeted health management measures and policies for incoming college students.

Methods

Data sources

The cross-sectional study was conducted from September 2023 to October 2023 at two universities in Xuzhou City, China (Xuzhou Medical University and Jiangsu Vocational Institute of Architectural Technology) during the college freshmen’s physical examination process organized by the college. The study employed a cluster sampling method, involving a total of 7,051 college freshmen who had graduated from high schools all over China. They were invited to complete the self-rated questionnaire through the Questionnaire Star platform (www.wjx.cn). The questionnaire covered basic demographic information, sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle habits, and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire. After excluding invalid data with incomplete basic information or missing content, we obtained 6,666 valid questionnaires with an effective response rate of 92.38%. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the affiliated hospital of Xuzhou Medical University (XYFY2023-KL396-01). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (e.g., Helsinki guidelines).

Measures

The first part of the questionnaire included the basic demographic information from their physical examination. It includes age, gender (male, female), and body mass index (BMI). Furthermore, BMI was categorized as follows: underweight (BMI < 18.5, kg/m2), normal weight (18.5 ≤ BMI < 24.0, kg/m2), overweight (24. 0 ≤ BMI < 28, kg/m2), and obesity (BMI ≥ 28, kg/m2)16.

The second part focused on sociodemographic data: college level (junior college, undergraduate), only child status (no, yes), father’s/mother’s educational level (high school or below, junior college, undergraduate or higher), family economic status (poor, fair, good), monthly living expenses (< 1000, 1000–2000, > 2000).

The third part focused on the lifestyle variables: smoking status in the past month (never, occasionally, always), drinking habits in the past month (never, occasionally, always), consumption of caffeinated beverages in the past month (do not drink, rarely drink (1–2 times/month), occasionally drink (1–2 times/week), frequently drink (3–5 times/week), drink very frequently (> 5 times/week)), daily usage time of electronic devices in the past month (1–2 h, 2–3 h, 3–4 h, 4–5 h, 5–6 h, 6 h or more), primary physical activity in the past month (leisure-related physical activity, computer games-related physical activity, travel-related physical activity, physical labor-related physical activity, mental labor-related physical activity, and other physical activities), the duration of exposure to natural light on each day (almost no, < 30 min, 30 min to 1 h, 1–2 h, > 2 h). Data on siesta was assessed by asking, “Did you have a habit of siesta during the past month?” Those who responded negatively were considered to have no siesta (0 min). Respondents who answered affirmatively were subsequently questioned regarding the siesta duration each time (10 min, 15 min, 20 min, 30 min, 45 min, 60 min, 120 min, 180 min). According to existing literature7,17,18, an ordinal variable with four categories was transformed: 0 min, 1–29 min, 30–59 min, and ≥ 60 min. Among individuals who habitually take siestas, the questionnaire also assessed factors associated with their siesta habits in the past month. The related variables were as follows: the frequency of siestas per week in the last month, sleep position (supine or prone), the duration between lunch and the siesta (0 min, 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, 60 min, > 60 min), the subjective rating of sleepiness before and after the siesta 30 min on a scale from “0” (extremely tired) to “9” (extremely awake), and the subjective rating of working effectiveness 30 min after the siesta (worse, generally, better).

The fourth section of the study involved the implementation of the PSQI questionnaire by translating it into a Chinese version to assess sleep quality. It consists of seven components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. The scores of each component are summed up, with the total score ranging from 0 to 2119. In this study, a PSQI score of 5 was the threshold, with a score greater than 5 indicating poor sleep quality and a score less than or equal to 5 indicating good sleep quality19,20. The Cronbach’s coefficient for the PSQI in this study was 0.80.

Statistical analysis

General characteristics are presented as frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables and mean ± standard deviation (SD for short) for continuous variables. Chi-square analysis was employed for categorical variables to compare the participants with groups. To continuous variables, when homoscedasticity was assumed, the means of two (or more) groups were compared by the t-test (or analysis of variance, ANOVA). However, if the assumption of homoscedasticity was not satisfied, the alternative approach of employing Welch’s t-test (or Welch’s ANOVA) was used. The post-hoc analysis was conducted using the Tukey’s method when the assumption of homoscedasticity was met, otherwise the Games-Howell’s test was employed. The Levene’s test was used to test the homoscedasticity. And the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for data with ordinal outcome. All the ordinal variables included in the model were converted to continuous form.

Statistical model

Multiple linear regression (MLR) model

The MLR model, with PSQI scores as the dependent variable, examines the relationship between sleep quality and all other variables. This analysis aimed to identify potential factors associated with sleep quality and determine the direction of their effects. The standard regression diagnostics are as follows21: (1) Exclude samples with extreme values (high leverage points, influential points, outliers). A total of 337 samples were removed from the model in this step. (2) Detect the residual’s independence by Durbin-Waston’s test. (3) Ensure the absence of multicollinearity via the variance inflation factor (VIF). All variables had VIF values less than 4, indicating the absence of multicollinearity. (4) Check the normality and homoscedasticity of residuals. These two assumptions were not met. Therefore, weighted MLR was employed to improve this situation. Specifically, by regressing the absolute values of the residuals against the fitted values and squaring the resulting fitted values, an estimate of the variance is obtained. (5) Assess the linearity between the dependent variable and explanatory variables. The diagnostic result for linearity, homoscedasticity, normality, and identification of extreme values was depicted in Figure S1 in supplementary materials.

Binary logistic regression (BLR) model

The BLR model was adopted to assess the relationship by odds ratios (OR). The standard regression diagnostics were conducted22: (1) In the MLR method above, 175 samples were excluded. (2) Assess multicollinearity by VIF. The results indicate no evidence of multicollinearity in the BLR model. (3) Use the Durbin–Waston test to test the independence of the data and confirm the validity of this assumption. (4) Examine the linear relationship between the log odds and the explanatory variables by conducting a regression analysis of the log odds against the explanatory variables. Figures S2 and S3 present the diagnostic results for linearity and extreme values. (5) Check overdispersion by Chi-square test. Moreover, the study satisfies the events per variable (EPV).

The analysis also examined the association between sleep quality and the different siesta duration (1–29 min, 30–59 min, ≥ 60 min), with no siesta as the reference group6. The model adjusted for various factors, including age, gender, college level, only child status, father’s and mother’s educational levels, smoking and drinking, consumption of caffeinated beverages, daily usage time of electronic devices, primary activity in the past month, duration of exposure to natural light, and BMI. Stratified analyses were performed by gender (male, female), and college level (junior college, undergraduate) to explore the relationship between sleep quality and different siesta duration. In the stratified analysis by college level, a highly imbalanced distribution of smoking status was found in the undergraduate college freshmen due to a low prevalence of smokers, so the smoking variable was omitted. The inclusion of independent variables was assessed through likelihood ratio tests to determine whether their addition significantly affects the variability in explaining the dependent variable.

Mediation analysis

The mediation analysis was conducted to explore the mediating effect of siesta characteristics on the siesta duration and sleep quality in habitual siesta. Different siesta durations were treated as the independent variables, with 1–29 min siesta as the reference group. Sleep quality was considered the dependent variable. Additionally, the remaining variables were included as covariates in the model. The 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated using the quasi-Bayesian Monte Carlo method with 5,000 iterations. All mediation analyses were adjusted for the same variables in BLR.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software of version 4.2.2. We employed R packages “mediation” for mediation analysis. The statistical significance level was defined as 0.05.

Results

Descriptive analysis

This research comprised 6,519 freshmen from 31 provincial-level administrative regions nationwide. Notably, 81.33% of participants were from Jiangsu Province, with Anhui Province following at 3.21%. The remaining 15.46% were from the other 29 regions (see Table S1 in supplementary materials).

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the total participants and their categorization based on sleep quality. Of the 6,519 participants, 30.63% of incoming college freshmen were categorized as having poor sleep quality. Among these individuals with poor sleep quality, a higher proportion were males (56.94%) compared to females (43.06%). The average PSQI score was 4.54 ± 2.63. In this study, 3,820 individuals self-reported having a habit of siesta, with the highest proportion in 30–59 min (51.54%). No significant differences were found in siesta duration (P > 0.05). Significant differences in sleep quality were observed in relation to gender, college level, only child status, father’s educational level, mother’s educational level, family economic status, monthly living expense, smoking status, drinking habits, consumption of caffeinated beverages, daily usage time of electronic devices, leisure-related physical activity, travel-related physical activity, duration of exposure to natural light (all P < 0.05). In contrast, no significant differences were observed for age, computer games-related physical activity, physical labor-related physical activity, mental labor-related physical activity, other physical activity, and BMI (all P > 0.05).

Moreover, junior college freshmen had a significantly higher average PSQI score (4.81 ± 2.77) than undergraduate college freshmen (4.01 ± 2.21) (P < 0.001) (see Table S2). Students with better sleep quality who were not only children and engaged in travel-related activities as their primary form of physical activity had significantly lower PSQI scores compared to their counterparts who were only children and did not engage in travel-related activities (P < 0.001).

The average PSQI scores of students whose parents had higher education levels were significant different from those of students with parents who had lower education levels (all P < 0.001). Students with poor family economic status, occasional smoking, and frequent drinking were more likely to have higher average PSQI scores compared to those with fair family economic status, non-smoking, and non-drinking. Significant differences exist between the different drinking habits (all P < 0.001). Moreover, each duration of exposure to natural light exhibited a significant decrease in average PSQI scores when compared to almost no exposure to natural light (all P < 0.001). Students who used electronic devices daily for 6 h or more tended to have higher PSQI scores than those who use electronic devices for 1–2 h, 2–3 h, and 3–4 h, respectively (all P < 0.05).

Among those participants with habitual siesta characteristics, as shown in Table 2, the average frequency of siestas per week was 4.59, and the predominant sleep position was supine. Additionally, 56.03% of the participants though that siesta could enhance their work efficiency. All siesta characteristics showed statistical significance within the siesta groups (all P < 0.05).

Analysis of affected factors related to sleep quality by weighted MLR

The Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) was calculated for both MLR and weighted MLR, resulting in values of 30,777.50 and 26,898.20, respectively. These results indicated that weighted MLR mitigated the bias caused by heteroscedasticity observed in MLR.

Table 3 shows the factors that affect sleep quality by weighted MLR regression. The variables gender (β = 0.37, P < 0.001), smoking status (β = 0.23, P < 0.001), drinking habits (β = 0.26, P < 0.001), consumption of caffeinated beverages (β = 0.11, P < 0.001), daily usage time of electronic devices (β = 0.11, P < 0.001), siesta duration (β = 0.10, P < 0.001), and computer games-related physical activity (β = 0.23, P = 0.004), BMI (β = 0.06, P = 0.048) showed a positive correlation with PSQI scores.

In contrast, college level (β = − 0.73, P < 0.001), only child status (β = − 0.19, P = 0.001), family economic status (β = − 0.56, P < 0.001), monthly living expense (β = − 0.41, P < 0.001), travel-related physical activity (β = − 0.20, P = 0.002) and duration of exposure to natural light (β = − 0.20, P < 0.001), demonstrated a negative correlation with PSQI scores. No significant association was observed with age, father’s educational level, mother’s educational level, leisure, physical labor, mental labor, and other physical activities related to primary physical activity (all P > 0.05).

Analysis of affected factors related to sleep quality by BLR

In the BLR model, prolonged siesta duration (OR = 1.08, P = 0.006) had an increased risk of sleep quality. Female college freshmen (OR = 1.49, P < 0.001) had a higher risk of poor sleep quality than male college freshmen. Besides, incoming college freshmen who reported higher frequency of smoking (OR = 1.18, P = 0.019), drinking (OR = 1.35, P < 0.001), and consumption of caffeinated beverages (OR = 1.08, P = 0.020), as well as longer daily usage time of electronic devices (OR = 1.09, P < 0.001) were statistically more likely to experience poor sleep quality.

On the other hand, incoming undergraduate freshmen (OR = 0.45, P < 0.001) had lower odds of experiencing poor sleep quality than incoming junior college freshmen. Participants who were only children (OR = 0.85, P = 0.020) had a lower risk of poor sleep quality compared to those who were not only child. Moreover, engaging in leisure (OR = 0.85, P = 0.014), travel (OR = 0.88, P = 0.043), and labor-related physical activity (OR = 0.85, P = 0.015) as the primary physical activity exhibited a protective effect on sleep quality. Prolonged exposure to natural light duration (OR = 0.82, P < 0.001) was associated with better sleep quality (Table 3). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of BLR can be found in Figure S3, and the area under curve (AUC) was 0.63.

Relation of siesta and sleep quality by mediation analysis

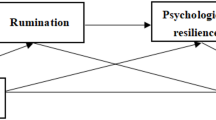

In the mediation analysis, Fig. 1 illustrates that several siesta characteristics mediated the relationship between different siesta duration and sleep quality. Specifically, the interval between lunch and the siesta, as well as the subjective rating of sleepiness 30 min after the siesta, were found to significantly mediate the association between 30-59 min siesta and ≥ 60 min with sleep quality, as compared to the 1–29 min siesta (P < 0.05). Moreover, sleep position was identified as a mediator in the relationship between 1-29 min siesta and sleep quality. It is noteworthy that the coefficient for the indirect effect (IE) of sleep position was −0.01, which exhibited an opposite directionality, suggesting a negative mediation effect. Siesta frequency, the subjective rating of working effectiveness 30 min after the siesta, the subjective rating of sleepiness before the siesta were not significant mediators of the relationship between siesta duration and sleep quality (Table S3).

Relation of sleep quality and siesta duration by BLR

The likelihood ratio test indicated the statistical significance of including siesta duration as the independent variable (P = 0.005). Upon controlling for all other covariates, it was observed in Table 4 that siesta duration of 1–29 min (OR = 1.21, P = 0.015), 30–59 min (OR = 1.15, P = 0.046), and ≥ 60 min (OR = 1.26, P = 0.024) exhibited a higher risk of poor sleep quality, compared to no siesta respectively.

The gender-stratified analysis found that only male freshmen showed a significant association between siesta duration of 30–59 min (OR = 1.22, P = 0.029) and poor sleep quality. No significant association was found in female freshmen. Upon stratified analysis at the college level, it was observed that siesta duration of 30–59 min (OR = 1.62, P = 0.001), and ≥ 60 min (OR = 1.67, P = 0.018) were identified as risk factors for poor sleep quality, compared with no siesta among incoming undergraduate freshmen. For incoming junior college students, siesta duration of 1–29 min (OR = 1.23, P = 0.024) was found to be a risk factor associated with poor sleep quality compared to no siesta.

Discussion

The cross-sectional study showed that longer siesta duration had an increased risk of poor sleep quality among incoming college freshmen. Further analysis revealed that each siesta duration was significantly associated with poor sleep quality compared to no siesta. Sleep position, the interval between lunch and the siesta, the subjective rating of sleepiness 30 min after the siesta mediated this relationship between sleep quality and siesta duration. In the stratified analysis, male students with siesta duration of 30–59 min, junior college freshmen with siesta duration of 1–29 min, and undergraduate freshmen with siesta duration of 30–59 min and ≥ 60 min had a higher risk of poor sleep quality compared to corresponding participants with no siesta.

In the current study, we observed that 30.63% of incoming college freshmen experienced poor sleep quality, which was consistent with the findings of Wang20 indicated a prevalent issue among students in China. According to our study results, several factors during the transitional period may contribute to declining sleep quality among these populations. Notably, the post-exam vacation period, free from academic pressures, may lead to lifestyle changes that affect sleep quality23. Additionally, the predominant engagement in computer gaming activities, reported by 45.66% of students, exposes them to increased blue light from screens, which can disrupt melatonin production and sleep24,25,26.

On the other hand, travel as a primary activity, reported by 46.28%, was associated with better sleep quality, likely due to the positive effects of outdoor activities and natural light exposure on psychological well-being and sleep regulation27. Engaging in outdoor activities not only promotes the production of the neurotransmitter serotonin, thereby regulating emotions and stress, but also exposes individuals to natural light, which aids in establishing a stable circadian rhythm and enhancing sleep quality28,29. This effect may be mediated by enhancing the amplitude and advancing the phase of circadian rhythms, which supports the normal secretion of melatonin, ultimately contributing to improved sleep quality30. Besides, students who engage in physical labor place a high priority on time management to ensure that they get sufficient sleep and maintain optimal energy levels. It is worth mentioning that engaging in leisure and physical labor as the primary physical activity did not exhibit a significant relationship with sleep quality in the weighted MLR. This discrepancy in the results may be attributed to the differences in diagnostic procedures and requirements between these two regression methods, leading to inconsistent sample inclusion and outcomes.

Consistent with prior research31,32, the present study found that, among the entire population of incoming college freshmen, females are more prone to poor sleep quality than males. This difference could be attributed to factors such as premenstrual syndrome symptoms, heightened mental health vulnerabilities, and increased smartphone usage24,33,34, all of which could lead to the exacerbation of their sleep problems. Furthermore, the study also found that smoking35, drinking36, and caffeine intake37 are factors that negatively impact sleep quality, consistent with previous research.

In this population, 58.70% of individuals reported having a habit of siesta, a common practice that enhances afternoon productivity and study efficiency, especially for those with sleep deprivation. However, prolonged siestas, particularly over 60 min, were linked to poorer sleep quality, consistent with the literature9,38. It has the potential to disrupt the natural sleep cycle and stem from dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, as well as the regulation of cortisol and melatonin in humans39.

Interestingly, when including all participants, all siesta durations were identified as a risk factor for poor sleep quality. Further stratified analysis has also revealed that different siesta durations have shown potential risk factors for sleep quality based on gender and college level. It was worth noting that a siesta duration of 1–29 min was widely regarded as beneficial for overall health in many studies6. This could be attributed to the fact that regardless of the siesta duration, if an individual obtains adequate or longer nighttime sleep, siesta behavior may positively impact poor sleep quality40. Moreover, a subset of students may have been accustomed to taking a siesta due to high school regulations, thereby establishing a habitual routine. This suggests that their siesta habit may not always serve to compensate for sleep deficiency, potentially leading to adverse effects on their nighttime sleep quality.

Previous research has highlighted a temporal relationship between siesta and sleep quality41, indicating that siesta may be a potential risk factor for sleep disturbances. The current study conducted a mediation analysis to explore how siesta characteristics influence the relationship between siesta and sleep quality. The mediation analysis revealed that factors such as sleep position, the interval between lunch and siesta, the subjective rating of sleepiness 30 min after the siesta mediate the association between them. Literature indicates that siesta significantly impacts overall cognition, typically involving N2 sleep and slow-wave sleep, which are associated with memory consolidation and cognitive function recovery42. Supine siesta position is often correlated with better sleep quality, possibly due to its alignment with the body’s physiological structure, reducing bodily and muscular pressure and facilitating faster entry into the sleep state43. Additionally, we found that the time interval between lunch and siesta mediates the relationship between siesta and sleep quality, suggesting that the body’s circadian rhythm influences the sleep–wake cycle. During the afternoon circadian dip, the body’s circadian rhythm may promote sleep, aligning siesta timing with natural sleep drive and potentially enhancing sleep quality44.

Compared with incoming junior college freshmen, incoming undergraduate freshmen had a higher risk of poor sleep quality, possibly due to the pressures of high school academic performance that can influence college admission and subsequently impact sleep quality20,45. Poor sleep quality can impair cognitive function and attention, thereby affecting academic achievements. Moreover, students with lower academic performance are prone to procrastination and may engage in late-night activities and excessive electronic device use, both of which can degrade sleep quality. The increased consumption of energy drinks among this group46,47, can also exacerbate sleep issues. A negative correlation between academic performance and sleep quality among students has been noted in various studies20,48. Our research extends prior work by encompassing a broader student demographic, highlighting the importance of considering the educational background when examining factors influencing sleep quality.

This study has extensively explored factors influencing the sleep quality of college students. However, several potential limitations of the current study should be considered. Firstly, the study overlooked other essential factors, such as diet and energy expenditure5, which are known to impact sleep quality. Considering that this population experiences lower levels of stress and possibly of experiencing anxiety and depression during holidays compared to their high school years, this study did not explore such factors. Secondly, the study’s assessment of caffeine intake was limited to the frequency of energy drink consumption, which may not fully capture the overall caffeine intake due to the presence of caffeine in other sources, such as chocolate37. Finally, as the study employed a cross-sectional design, causality cannot be determined, and caution is warranted when interpreting the research conclusions. Moreover, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of recall bias, potentially affecting the credibility and accuracy of the research findings. Therefore, future research should take a more comprehensive approach to considering these underlying factors to accurately evaluate the factors influencing the sleep quality of college freshmen.

Several strengths of this study warrant acknowledgment. Firstly, this research aims at incoming college freshmen from different college levels, benefits from a larger sample size (n = 6,519), and provides a comprehensive groundwork for investigating the influence of college environments on student behavior. It also encompassed diverse educational backgrounds and ensured the representative nature of the research findings. Secondly, various regression analyses were utilized to assess the consistency and robustness of the study. Furthermore, we conducted rigorous diagnostics of the regression model. This step is often overlooked in previous studies. However, accurately assessing the model’s applicability is crucial for producing reliable and generalizable results. With these strengths, our research can provide comprehensive and reliable findings.

Deterioration in sleep quality is a prevalent phenomenon among incoming college freshmen. Research indicates that as the grade level increases, students face growing pressures, leading to a gradual decline in sleep quality5,49,50. Therefore, paying attention to the sleep quality of college freshmen at the beginning of their university experience, specifically during the transition period following college entrance exams, is crucial. Based on the findings, this study can provide a basis for relevant departments to develop scientific measures to promote and prevent sleep-related issues specifically targeting the freshman population. For instance, increasing physical activity and raising awareness among students about the factors that affect poor sleep quality can help improve their sleep and overall well-being51. By implementing these measures, we can create a better sleep environment for college students, promoting their health and academic achievement.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that both siesta duration and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors adversely affect the sleep quality of incoming college freshmen, with certain characteristics of siesta serving as mediators in the relationship between siesta duration and sleep quality. Specifically, siesta durations ≥ 30 min are associated with poor sleep quality among male college freshmen and undergraduate freshmen, respectively. However, this adverse relationship has not been observed in female college freshmen. These findings highlight the need for parents and educational institutions to promote healthy siesta practices and develop targeted interventions for at-risk incoming college freshmen. Emphasizing the impact of siesta duration on sleep quality is essential. Future research should further investigate the underlying mechanisms and gender differences in sleep quality outcomes.

Data availability

The dataset used in the present study can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author with reasonable request.

Code availability

The source R codes and execution results of the present study can be downloaded in the following hyperlink: https://gitee.com/xiaostat/SleepqualityandSiesta.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance"

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criteria

- BLR:

-

Binary logistic regression

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EPV:

-

Events per variable

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh sleep quality index

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor

- MLR:

-

Weighted multiple linear regression

References

Chen, Y. & Kesten, O. Chinese college admissions and school choice reforms: A theoretical analysis. J. Polit. Econ. 125, 99–139. https://doi.org/10.1086/689773 (2017).

Sejbuk, M., Mirończuk-Chodakowska, I. & Witkowska, A. M. Sleep quality: A narrative review on nutrition, stimulants, and physical activity as important factors. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091912 (2022).

Chellappa, S. L. & Aeschbach, D. Sleep and anxiety: From mechanisms to interventions. Sleep Med. Rev. 61, 101583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101583 (2022).

Riemann, D. Sleep, insomnia and anxiety-Bidirectional mechanisms and chances for intervention. Sleep Med. Rev. 61, 101584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101584 (2022).

Wang, F. & Bíró, É. Determinants of sleep quality in college students: A literature review. Explore 17, 170–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2020.11.003 (2021).

Vizmanos, B. et al. Lifestyle mediators of associations among siestas, obesity, and metabolic health. Obesity 31, 1227–1239. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23765 (2023).

Ji, X., Li, J. & Liu, J. The relationship between midday napping and neurocognitive function in early adolescents. Behav. Sleep Med. 17, 537–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2018.1425868 (2019).

Mesas, A. E. et al. Is daytime napping an effective strategy to improve sport-related cognitive and physical performance and reduce fatigue? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 57, 417–426. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2022-106355 (2023).

Mizuno, K., Okamoto-Mizuno, K. & Iwata, K. Napping behaviors and extracurricular club activities in Japanese high school students: associations with daytime sleep problems. Clocks Sleep 1, 367–384. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep1030030 (2019).

Komada, Y. et al. Relationship between napping pattern and nocturnal sleep among Japanese nursery school children. Sleep Med. 13, 107–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2011.10.017 (2012).

Leong, R. L. F. et al. Bidirectional associations between the duration and timing of nocturnal sleep and daytime naps in adolescents differ from weekdays to weekends. Sleep https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsae147 (2024).

Santos, J. S., Pereira, S. I. R. & Louzada, F. M. Chronic sleep restriction triggers inadequate napping habits in adolescents: a population-based study. Sleep Med. 83, 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.04.016 (2021).

Tang, D., Zhou, Y., Long, C. & Tang, S. The association of midday napping with hypertension among Chinese adults older than 45 years: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 8, e38782. https://doi.org/10.2196/38782 (2022).

Sun, J., Ma, C., Zhao, M., Magnussen, C. G. & Xi, B. Daytime napping and cardiovascular risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 65, 101682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101682 (2022).

Zhou, L. et al. Sleep duration, midday napping, and sleep quality and incident stroke: The Dongfeng-Tongji cohort. Neurology 94, e345–e356. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000008739 (2020).

Liu, P. et al. Obesity and cardiac conduction block disease in China. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2342831. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.42831 (2023).

Wang, K. et al. Midday napping, nighttime sleep, and mortality: Prospective cohort evidence in China. Biomed. Environ. Sci. BES 36, 702–714. https://doi.org/10.3967/bes2023.073 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Effects of nighttime sleep duration and sex on the association between siesta and hypertension. Sleep Med. 82, 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.04.005 (2021).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F. 3rd., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28, 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 (1989).

Wang, L. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of poor sleep quality among Inner Mongolia Medical University students: A cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 244, 243–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.011 (2016).

Kabacoff, R. I. R in action: Data analysis and graphics with R, Second edition. (Manning, 2015)

Kabacoff, R. I. R in Action: Data Analysis and Graphics with R. (Manning, 2011)

Ceballos, N. A., Sharma, S., Patterson, T. L., Graham, R. & Howard, K. Stress, immune function and collegiate holiday drinking: A pilot study. Neuropsychobiology 72, 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1159/000438757 (2015).

Demirci, K., Akgönül, M. & Akpinar, A. Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. J. Behav. Addictn. 4, 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.010 (2015).

Hershner, S. D. & Chervin, R. D. Causes and consequences of sleepiness among college students. Nat. Sci. Sleep 6, 73–84. https://doi.org/10.2147/nss.S62907 (2014).

Mustafaoglu, R., Yasaci, Z., Zirek, E., Griffiths, M. D. & Ozdincler, A. R. The relationship between smartphone addiction and musculoskeletal pain prevalence among young population: a cross-sectional study. Korean J. Pain 34, 72–81. https://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.2021.34.1.72 (2021).

White, R. L. et al. Domain-specific physical activity and affective wellbeing among adolescents: an observational study of the moderating roles of autonomous and controlled motivation. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 15, 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0722-0 (2018).

Rutherford, E. R., Vandelanotte, C., Chapman, J. & To, Q. G. A NHANES ssociations between depression, domain-specific physical activity, and BMI among US adults: 2011–2014 cross-sectional data. BMC Public Health 22, 1618. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14037-4 (2022).

Didikoglu, A. et al. Associations between light exposure and sleep timing and sleepiness while awake in a sample of UK adults in everyday life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 120, e2301608120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2301608120 (2023).

Burns, A. C. et al. Time spent in outdoor light is associated with mood, sleep, and circadian rhythm-related outcomes: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study in over 400,000 UK Biobank participants. J. Affect. Disord. 295, 347–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.056 (2021).

Verlinden, J. J., Moloney, M. E., Whitehurst, L. N. & Weafer, J. Sex differences in the association between poor sleep quality and alcohol-related problems among heavy drinkers with insomnia. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 16, 875168. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2022.875168 (2022).

Eleftheriou, A., Rokou, A., Arvaniti, A., Nena, E. & Steiropoulos, P. Sleep quality and mental health of medical students in Greece during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 9, 775374. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.775374 (2021).

de Lima, T. R. & Silva, D. A. S. Association of sleep quality with sociodemographic factors and lifestyle in adolescents from southern Brazil. World J. Pediatr. WJP 14, 383–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-018-0136-8 (2018).

Huang, Q. et al. Smartphone use and sleep quality in Chinese college students: A preliminary study. Front. Psychiatry 11, 352. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00352 (2020).

Dugas, E. N. et al. Nicotine dependence and sleep quality in young adults. Addict. Behav. 65, 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.10.020 (2017).

Meneo, D. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between young adults’ sleep habits and substance use, with a focus on self-medication behaviours. Sleep Med. Rev. 70, 101792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101792 (2023).

Riera-Sampol, A., Rodas, L., Martínez, S., Moir, H. J. & Tauler, P. Caffeine intake among undergraduate students: Sex differences, sources, motivations, and associations with smoking status and self-reported sleep quality. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14081661 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Association of midday napping with all-cause mortality in Chinese adults: A 8-year nationwide cohort study. Behav. Med. 49, 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2022.2061411 (2023).

Ye, L., Hutton Johnson, S., Keane, K., Manasia, M. & Gregas, M. Napping in college students and its relationship with nighttime sleep. J. Am. Coll. Health 63, 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2014.983926 (2015).

Linz, D., Kadhim, K., Kalman, J. M., McEvoy, R. D. & Sanders, P. Sleep and cardiovascular risk: how much is too much of a good thing?. Eur. Heart J. 40, 1630–1632. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy772 (2019).

Jakubowski, K. P., Hall, M. H., Lee, L. & Matthews, K. A. Temporal relationships between napping and nocturnal sleep in healthy adolescents. Behav. Sleep Med. 15, 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2015.1126595 (2017).

Alger, S. E., Lau, H. & Fishbein, W. Slow wave sleep during a daytime nap is necessary for protection from subsequent interference and long-term retention. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 98, 188–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2012.06.003 (2012).

Zhao, D., Zhang, Q., Fu, M., Tang, Y. & Zhao, Y. Effects of physical positions on sleep architectures and post-nap functions among habitual nappers. Biol. Psychol. 83, 207–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.12.008 (2010).

Lastella, M., Halson, S. L., Vitale, J. A., Memon, A. R. & Vincent, G. E. To nap or not to nap? A systematic review evaluating napping behavior in athletes and the impact on various measures of athletic performance. Nat. Sci. Sleep 13, 841–862. https://doi.org/10.2147/nss.S315556 (2021).

Curcio, G., Ferrara, M. & De Gennaro, L. Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Med. Rev. 10, 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2005.11.001 (2006).

Kim, S. Y., Sim, S. & Choi, H. G. High stress, lack of sleep, low school performance, and suicide attempts are associated with high energy drink intake in adolescents. PLoS One 12, e0187759. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187759 (2017).

Kim, J., Park, G. R. & Sutin, A. R. Adolescent sleep quality and quantity and educational attainment: a test of multiple mechanisms using sibling difference models. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discipl. 63, 1644–1657. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13686 (2022).

Peltzer, K. & Pengpid, S. Nocturnal sleep problems among university students from 26 countries. Sleep Breath. Schlaf Atmung 19, 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-014-1036-3 (2015).

Albqoor, M. A. & Shaheen, A. M. Sleep quality, sleep latency, and sleep duration: a national comparative study of university students in Jordan. Sleep Breath. Schlaf Atmung 25, 1147–1154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-020-02188-w (2021).

Zhou, Y. et al. Deteriorated sleep quality and influencing factors among undergraduates in northern Guizhou, China. PeerJ 10, e13833. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13833 (2022).

Memon, A. R. et al. Sleep and physical activity in university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 58, 101482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101482 (2021).

Funding

This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 12001470 and 12171471), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2020M671607).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed to and approved this final manuscript of this work. L.X. and G.S. supplied the conceptualization and methodology; P.S. supervised the project organization and reviewed the manuscript; Y.H. participated in designing the study; L.Y. and S.Z. were responsible for data collection, statistical analysis, writing the original manuscript; H.W. and J.L. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Li, J., Han, Y. et al. Siesta characteristics mediated the association between siesta duration and sleep quality in Chinese incoming college freshmen. Sci Rep 14, 31877 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83291-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83291-w