Abstract

Extubation failure rates are notably high in patients in neurointensive care. Ineffective cough is the variable independently associated with extubation failure, but its quantification remains challenging. Patients with primary central nervous system injury requiring invasive mechanical ventilation were included. After a successful spontaneous breathing trial (SBT), abdominal muscles and diaphragm ultrasound were performed under tidal breathing and coughing. 98 patients were initially recruited for the study, and 40 patients were ultimately included in the final analysis. Extubation failure occurred in 8 (20%) patients. Rectus abdominis (RA) and internal oblique (IO) muscles showed difference regarding cough thickening fraction (TF) between the extubation success and failure group (P < 0.05). The logistic regression that analysis suggested cough TFRA, cough TFIO and cough TIO were the factors associated with extubation outcome (P < 0.05). In the receiver operating characteristic analysis, cough TFIO exhibited the strongest predictive value (AUC = 0.957, 95% CI:0.8979–1). A threshold of cough TFIO ≥ 34.15% predicted extubation success with a sensitivity of 93.8% and specificity of 75%. Abdominal muscles ultrasound was a promising tool to predict extubation for patients requiring neurointensive care.

Trial registration: The study was registered on Chinese Clinical Trial Registry: ChiCTR2400088210, Registered 13 August 2024 - Retrospectively registered, https://www.chictr.org.cn/bin/project/edit?pid=234150.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extubation is the final step in weaning patients from mechanical ventilation in intensive care units (ICUs) and directly affects patient outcomes1. In neurointensive care units (NICUs), patients with primary or secondary brain injuries often face complications such as impaired central respiratory drive2, loss of airway protective reflexes, altered consciousness levels, and respiratory muscle fatigue3. As a result, extubation failure rates in this population are higher than in the general ICU population, ranging from 20–40%4. The decision to extubate in NICUs is particularly challenging, as both extubation failure and delayed extubation can increase the need for tracheostomy and lead to higher mortality rates4,5,6,7. While there are established guidelines for weaning from mechanical ventilation, specific international extubation guidelines for NICU patients are lacking.

Successful extubation in patients requiring neurointensive care depends on a combination of factors, including the patient’s level of arousal, airway protection ability, and overall clinical condition8. However, a 2020 expert consensus from the European Society of Critical Care Medicine stated that consciousness level is not a reliable predictor of extubation success, while ineffective cough was independently associated with extubation failure9. Currently, cough is primarily assessed using clinical scales, but these are subjective and have limited predictive value, with an odds ratio of 0.64. Cough peak flow can serve as an objective measure of cough strength, but it requires patient cooperation, and its predictive ability remains insufficient10,11.

Abdominal muscles, which are the primary drivers of coughing, may serve as valuable indicators for predicting extubation outcome. Abdominal muscle ultrasound, due to its non-invasive nature, ability to measure non-volitionally, and excellent reproducibility12, is particularly useful for pre-extubation assessment in NICU patients who are unable to cooperate because of impaired consciousness. Schreiber et al. found that the thickening fraction of the transversus abdominis and rectus abdominis muscles was associated with expiratory pressure, and a reduced cough thickening fraction of these muscles could predict the risk of extubation failure13. However, since their study included a general ICU population, these findings may not be directly applicable to NICU patients, who are at a higher risk of extubation failure. Additionally, Spadaro et al. proposed that abdominal muscle ultrasound could be useful for predicting reintubation14, though this hypothesis requires further investigation.

This study was designed to combine diaphragm and abdominal muscle ultrasound as a pre-extubation assessment in patients requiring neurointensive care, aiming to analyze their predictive value for extubation outcomes.

Methods

This prospective observational cohort study was conducted over 8 months, from December 2023 to July 2024, in the Neurology ICU of a tertiary hospital. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with approval from the institutional ethics committee. The trial was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2400088210), and informed consent was obtained from the legal representative of each participant.

Eligibility criteria

Participants in this study were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) patients aged 18 to 80 years, admitted to the NICU with planned extubation after at least 48 h of invasive mechanical ventilation; (2) patients with primary central nervous system injury, including stroke, status epilepticus, and infectious encephalopathies. The exclusion criteria were: (1) severe brainstem injury leading to an inability to breathe or cough spontaneously, such as bulbar dysfunction; (2) a history of abdominal surgery; (3) uncontrolled respiratory or circulatory conditions, including heart failure, pneumothorax, severe emphysema, pulmonary hypertension, or uncontrolled asthma.

Extubation protocol

Extubation decisions were made by physicians who were not involved in the study and were blinded to the study results. Before extubation, patients had to meet the following criteria: hemodynamic stability without the use of vasoactive drugs, a successful breathing trial (SBT) lasting at least 30 min, a successful cuff leak test, a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) < 40%, and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) < 5 cmH₂O. After passing the SBT, patients received high-flow oxygen therapy at 40–50 L/min as a transition period before extubation. All pre-extubation assessments were performed during this transition phase. Patients were monitored for 48 h following extubation.

Data collection

Demographic and clinical characteristics, including age, sex, diagnosis, intubation method, intubation diameter, duration of mechanical ventilation, weaning process, and ICU stay, were collected. Ultrasound examinations were performed prior to extubation, after the successful completion of the SBT trial. Extubation failure was defined as reintubation or the initiation of unplanned non-invasive ventilation within 48 h after extubation15.

Measurements

The ultrasonography device used in this study was the GE LOGIQ E10s, equipped with a 10–15 MHz linear probe and a 3.5–5 MHz phased array probe. Ultrasound examinations were performed by a qualified physiotherapist with specialized training and 3 years of hands-on experience. The ultrasound evaluator did not participate in the extubation decision-making process, and the assessment results were not made available to the decision-makers. All measurements were taken with the patients in the supine position. To minimize variability, each measurement was repeated three times at the same location, and the average value was used for analysis.

Abdominal muscle ultrasound

A high-frequency (10–15 MHz) linear array transducer was placed midway between the 12th rib and the iliac crest along the anterior axillary line to measure the external oblique (EO), internal oblique (IO), and transversus abdominis (TrA) muscles. For rectus abdominis (RA), the probe was positioned 2 to 3 cm above the umbilicus and 2 to 3 cm to the right of the midline16. Care should be taken to minimize pressure on the probe to avoid compressing the abdominal wall, as this can alter the thickness of the underlying muscles16.

Each muscle was first identified using B-mode imaging, and its thickness was then measured in M-mode. Abdominal muscle thickness was assessed during tidal breathing and coughing. In our study, all participants underwent stimulated cough due to impaired consciousness and severe brain injury, which prevented them from following cough commands. Coughing was induced either by pinching the suprasternal trachea or by inserting a sputum suction tube into the airway. Muscle thickness was measured at both end-inspiration (Tei) and maximum cough (Tcough), as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Muscle thickness is defined as the distance between the inner layers of each muscle, excluding the surrounding aponeurosis. The cough thickening fraction of abdominal muscles (cough TFabd) was calculated as the percent change in thickness between end-inspiration and maximum cough: cough TFabd = ((Tcough - Tei) / Tei) × 100%.

Diaphragm ultrasound

Diaphragm excursion (DE) is measured using a 3.5–5 MHz phased array probe, which is placed below the right costal arch along the midclavicular line. The probe is oriented perpendicular to the movement of the diaphragm dome. M-mode imaging is then used to capture the motion of the anatomical structures along the selected line. DE is defined as the vertical distance between the starting point (beginning of inhalation) and the peak point (end of inhalation), while DE-Inspiratory time (s) is the horizontal distance between these two points. The DE-contraction speed (cm/s) is calculated as the slope of the DE and DE-Inspiratory time17.

Diaphragm thickness(DT) is measured using a high-frequency (10–15 MHz) linear array probe, placed perpendicular to the long axis of the ribs or parallel to the intercostal space, between the 8th and 11th intercostal spaces along the anterior or midaxillary line. Thickness measurements are recorded at the end of inspiration (Tei) and the end of expiration (Tee). The thickening fraction (TF) is calculated using M-mode, with the formula: TF = (Tei - Tee) / Tee.

Statistical analysis

The normality of continuous variables was assessed using Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Based on the results, variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± SD, while those with non-normal distribution were presented as median (range). For analysis, two-independent sample t-tests were used for normally distributed variables, and Mann–Whitney U tests were applied to non-normally distributed variables. Chi-squared tests were used to compare categorical variables. Logistic regression was employed to assess the association between abdominal muscle and diaphragm function and the risk of extubation failure. Indicators significantly related to extubation failure were further evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to differentiate between extubation success and failure. The optimal cutoff point was determined based on the Youden Index, which balances sensitivity and specificity. All statistical tests were two-sided, with P values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 26.0.

Given that the extubation failure rate in neurointensive care patients is approximately 20%4, a sample size of 8 from the positive group and 32 from the negative group provides 81% power to detect a difference of 0.3000 in the area under the ROC curve (AUC). This calculation assumes a null hypothesis AUC of 0.8000 and an alternative hypothesis AUC of 0.5000, using a two-sided z-test at a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Of the 98 patients who were mechanically ventilated during the study period, 76 were extubated after 48 h of ventilation. Among them, 36 patients were excluded for reasons outlined in Fig. 3. The remaining 40 patients were included in the analysis, of which 8 (20%) failed extubation. Demographic variables were similar between the extubation failure group and the success group, as shown in Table 1. Neither the intubation method (oral or nasal) nor the intubation diameter influenced the extubation outcome. The most common neurological condition in the cohort was stroke (N = 31). In the extubation failure group, the duration of mechanical ventilation was significantly longer, ranging from 222.75 h to 399.75 h (median: 315.5 h). Additionally, ICU length of stay was also significantly extended, ranging from 471.25 h to 627.75 h (median: 533.63 h).

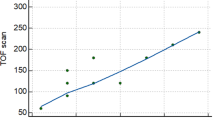

Based on the diaphragm and abdominal muscle ultrasound evaluation before extubation, significant differences in cough thickening fraction were observed between the groups, as shown in Table 2; Fig. 4. Specifically, the cough TFRA was 49.15% (38.67–56.05) in the successful extubation group and 29.40% (23.97–34.37) in the failed extubation group. The cough TFIO was 82.04% (50.91-111.12) in the successful extubation group and 29.37% (22.93–37.50) in the failed extubation group. Logistic regression analysis indicated that cough TFRA, cough TFIO, and cough TIO were significantly associated with extubation outcome (P < 0.05), as detailed in Table 3. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis revealed that cough TFIO had the strongest predictive ability for extubation failure (AUC = 0.957, 95% CI: 0.8979–1). Cough TFRA and cough TIO also demonstrated good predictive performance (AUC = 0.8945, 95% CI: 0.797–0.9921; AUC = 0.7617, 95% CI: 0.5936–0.9298), as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Based on the Youden Index, the optimal cutoff point for cough TFIO, which provided the highest discriminative capacity, was ≥ 41.52%, yielding a sensitivity of 90.6% and a specificity of 100%. However, in intensive care practice, an indicator with higher sensitivity—one that can more effectively identify patients with a higher likelihood of extubation success—may be more useful. Therefore, we adjusted the cutoff point to ≥ 34.15%, which resulted in a sensitivity of 93.8% and a specificity of 75%.

Discussion

In a monocentric prospective cohort of neurologically critical patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation, we found that abdominal muscle ultrasound assessment before extubation could be a promising tool for predicting extubation outcomes in the NICU.

Effective cough is a prerequisite for successful extubation18 and and ineffective cough is independently associated with extubation failure19. In our study, we used abdominal muscle ultrasound to measure the thickness and thickening fraction of the abdominal muscles during coughing, comparing patients with successful and failed extubation. The results showed that Cough TFIO, Cough TFRA, and Cough TIO all had high predictive value for extubation. Among these, Cough TFIO had the largest AUC value, with a threshold ≥ 34.15% predicting successful extubation. Schreiber et al. found that the thickening fraction of the IO and RA muscles was related to expiratory pressure, and reduced thickening scores during coughing were associated with a higher risk of weaning failure13. This may explain the high predictive value of the IO and RA muscles. Abdominal muscles are crucial for the cough reflex, as they help expel secretions20 and play a direct role in airway protection and extubation outcomes21. Despite their importance, clinical evidence regarding abdominal muscles is limited, and some researchers emphasize the need to recognize the role of expiratory muscles22. Therefore, further research is needed to explore whether early intervention targeting abdominal muscles can reduce the extubation failure rate in patients requiring neurocritical care.

Diaphragm ultrasound can reflect diaphragm function but cannot predict extubation19. In our study, we found that diaphragm excursions and contraction speed measured during tidal breaths were lower in EF patients, compared with patients who were successfully extubated. However, the difference is not significant and cannot be used as an indicator to predict extubation. This result was also confirmed in a study on prediction of extubation in patients with neurocritical care10 and a multicenter study19, but it should be noted that the neurocritical care study10 had a small sample size, and the results should be interpreted with caution. Diaphragm ultrasound may be more valuable before SBT and it can reflect whether the patient has the ability to breathe spontaneously23,24. However, for patients who have passed the SBT, diaphragm function is no longer the determining factor for extubation. Instead, patient’s adequate expectoration ability should be considered19. Although our findings may differ from existing evidence25, the reason may be that there is some overlap in the definitions of weaning and extubation. Many studies focus on the weaning process, while fewer studies specifically address the evaluation of extubation. Future research may be needed to further investigate the specific assessment criteria for predicting extubation outcomes.

The combined use of multiple tools to predict weaning outcomes has been well-supported by numerous studies. Specifically, the combination of diaphragm ultrasound and the RSBI index has demonstrated high accuracy in predicting successful weaning from mechanical ventilation26,27. In this study, we evaluated extubation readiness using both diaphragm and abdominal muscle ultrasound; however, diaphragm ultrasound was performed during quiet breathing, which does not reflect the diaphragm’s function during coughing. This limitation may explain why diaphragm ultrasound was not a reliable predictor of extubation outcomes in our trial. Coughing itself involves several phases, including the deep inspiration phase, glottic closure, and the vigorous expulsion phase, with the diaphragm playing a crucial role in the inspiratory phase20. A sufficient inspiratory volume is necessary to generate an effective cough. Therefore, future research should focus on simultaneously measuring changes in both the diaphragm and abdominal muscles during the cough reflex, to better understand their combined predictive value for extubation success.

Our research has several limitations. The sample size is limited and it is a single-center study, so the findings need to be confirmed in a large cohort. This experiment did not compare cough peak flow, and this work needs to be completed in the future. Additionally, patients with neurological damage may have specific physiological characteristics related to respiratory function and cough ability. These characteristics could impact the generalizability and applicability of the study’s findings. Therefore, future researchers should consider these factors to better understand how they may influence the outcomes.

Conclusion

In a monocentric prospective cohort study, we found that abdominal muscle ultrasound, particularly of the rectus abdominis and internal oblique muscles, holds promise as a tool for predicting extubation in patients requiring neurointensive care. However, these findings should be validated in a larger cohort to confirm their applicability.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- DE:

-

Diaphragm excursion

- DTF:

-

Diaphragm thickening fraction

- ei:

-

End-inspiratory

- RA:

-

Rectus abdominis

- EO:

-

External oblique muscle

- IO:

-

Internal oblique muscle

- TrA:

-

Transversus abdominis

- IMV:

-

Invasive mechanical ventilation

- IQR:

-

Inter‑quartile range

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- SBT:

-

Spontaneous breathing trial

- NIV:

-

Non‑invasive ventilation

- T:

-

Thickness

- TF:

-

Thickening fraction

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

References

Boles, J. M. et al. Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Eur. Respir J. 29(5), 1033–1056. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00010206 (2007).

Benghanem, S. et al. Brainstem dysfunction in critically ill patients. Crit. Care Lond. Engl. 24(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2718-9 (2020).

da Silva, A. R., Novais, M. C. M., Neto, M. G. & Correia, H. F. Predictors of extubation failure in neurocritical patients: A systematic review. Aust Crit. Care 36(2), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2021.11.005 (2023).

Thille, A. W. et al. Role of ICU-acquired weakness on extubation outcome among patients at high risk of reintubation. Crit. Care Lond. Engl. 24(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2807-9 (2020).

Steidl, C. et al. Tracheostomy, extubation, reintubation: Airway management decisions in intubated stroke patients. Cerebrovasc. Dis. Basel Switz. 44(1–2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000471892 (2017).

Z, X. J. Impact of delay extubation on the reintubation rate in patients after cervical spine surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J. Orthop. Surg. 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-04008-9 (2023).

Rothaar, R. C. & Epstein, S. K. Extubation failure: magnitude of the problem, impact on outcomes, and prevention. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care. 9(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/00075198-200302000-00011 (2003).

Cinotti, R. et al. Extubation in neurocritical care patients: the ENIO international prospective study. Intensive Care Med. 48(11), 1539–1550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-022-06825-8 (2022).

Robba, C. et al. Mechanical ventilation in patients with acute brain injury: recommendations of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine consensus. Intensive Care Med. 46(12), 2397–2410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06283-0 (2020).

Hirolli, D., Srinivasaiah, B., Muthuchellappan, R. & Chakrabarti, D. Clinical scoring and ultrasound-based diaphragm assessment in predicting extubation failure in neurointensive care unit: A single-center observational study. Neurocrit Care. 39(3), 690–696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-023-01695-4 (2023).

Lombardi, F. S. et al. Prediction of extubation failure in Intensive Care Unit: systematic review of parameters investigated. Minerva Anestesiol 85(3), 298–307. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0375-9393.18.12627-7 (2019).

Reliability of B-mode sonography of the abdominal muscles in healthy adolescents in different body positions. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24866612/ (2024).

Schreiber, A. F. et al. Abdominal muscle use during spontaneous breathing and cough in patients who are mechanically ventilated: A bi-center ultrasound study. Chest 160(4), 1316–1325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.053 (2021).

Spadaro, S., Scaramuzzo, G. & Volta, C. A. Can abdominal muscle ultrasonography during spontaneous breathing and cough predict reintubation in mechanically ventilated patients? Chest 160(4), 1163–1164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.006 (2021).

Sk, A. Prediction of extubation failure following mechanical ventilation: Where are we and where are we going? Crit. Care Med. 48(10). https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000004536 (2020).

Tuinman, P. R. et al. Respiratory muscle ultrasonography: methodology, basic and advanced principles and clinical applications in ICU and ED patients—a narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 46(4), 594–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05892-8 (2020).

Sarwal, A., Walker, F. O. & Cartwright, M. S. Neuromuscular ultrasound for evaluation of the diaphragm. Muscle Nerve 47(3), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.23671 (2013).

Bureau, C. & Demoule, A. Weaning from mechanical ventilation in neurocritical care. Rev. Neurol. (Paris). 178(1–2), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2021.08.005 (2022).

Vivier, E. et al. Inability of diaphragm ultrasound to predict extubation failure: A multicenter study. Chest 155(6), 1131–1139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.03.004 (2019).

McCool, F. D. Global physiology and pathophysiology of cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 129(1 Suppl), 48S–53S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.48S (2006).

Shi, Z. H. et al. Expiratory muscle dysfunction in critically ill patients: towards improved understanding. Intensive Care Med. 45(8), 1061–1071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05664-4 (2019).

Laghi, F. & Cacciani, N. Expiratory muscles, neglected no more. Anesthesiology 134(5), 680–682. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003753 (2021).

Bp, D. Ultrasound evaluation of diaphragm function in mechanically ventilated patients: comparison to phrenic stimulation and prognostic implications. Thorax 72(9). https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209459 (2017).

Dres, M. et al. Coexistence and impact of limb muscle and diaphragm weakness at time of liberation from mechanical ventilation in medical intensive care unit patients. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 195(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201602-0367OC (2017).

Truong, D. et al. Methodological and clinimetric evaluation of inspiratory respiratory muscle ultrasound in the critical care setting: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care Med. 51(2), e24–e36. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005739 (2023).

Pirompanich, P. & Romsaiyut, S. Use of diaphragm thickening fraction combined with rapid shallow breathing index for predicting success of weaning from mechanical ventilator in medical patients. J. Intensive Care 6, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-018-0277-9 (2018).

Song, J. et al. Diaphragmatic ultrasonography-based rapid shallow breathing index for predicting weaning outcome during a pressure support ventilation spontaneous breathing trial. BMC Pulm. Med. 22(1), 337. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-022-02133-5 (2022).

Funding

The study is funded by the Startup Fund for Scientific Research of Fujian Medical University (2021QH1099) and Rehabilitation Medicine Center Open research fund (2023YKFKF-04). The funding body has no influence on the design of the study, data collection, analysis of data, interpretation of data, or writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XQ designed the study and drafted the manuscript. CJC and BHY collected the clinical data. LL analyzed data. ZQW and JN critically revised the manuscript and contributed in experimental design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study got the approval of the local ethics committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China (MRCTA, ECFAH of FMU [2024] 380). The contacts of the ethics committee are: 0086–0591 − 87,981,028, fykyll@163.com, and No.20, Chazhong Road, Fuzhou, Fujian Province, China. Participants’ legal representative sign an informed consent form before this study.

Consent for publication

All results are reported as group-level statistics (e.g., means, standard deviations) and tracing to the person level is not possible. The manuscript does not contain any person’s individual data in any form.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, X., Chen, C., Lv, L. et al. Ultrasound-based abdominal muscles and diaphragm assessment in predicting extubation failure in patients requiring neurointensive care: a single-center observational study. Sci Rep 15, 2639 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83325-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83325-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Spontaneous breathing trials as predictors of extubation outcomes in neurocritical care: insights from the ENIO study

Intensive Care Medicine (2026)

-

Multi-view ultrasound for diaphragm monitoring and cough strength estimation

Communications Medicine (2025)

-

Diaphragm Ultrasound for Assessing Diaphragmatic Function and Predicting Ventilator Weaning Success: A Review of the Literature

Current Pulmonology Reports (2025)