Abstract

Ambient air pollution exposure was associated with an increased risk of incident cancer, but few previous studies have focused on the associations between ambient air pollution and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Thus, our goal is to examine whether exposure to ambient air pollution in Hangzhou, which includes sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and inhalable particles (PM10), will have an impact the risk of incident cancer. We collected data on daily ambient air pollution data, climate, and daily incidence of NPC in Hangzhou from Jan 1, 2013, to Dec 31, 2022. We applied a generalized additive model (GAM) based on the Poisson distribution to investigate the effect of ambient air pollution on the risk of incident NPC. The effects of ambient air pollution exposure on NPC were also discussed in subgroups by age, gender, region, and season. A total of 3121 NPC incident cases were included during the study period. We discovered that the risk of incident NPC was increased by 0.75% (95% CI: 0.01–1.58), 0.36% (95% CI: 0.03–0.69), and 0.14% (95% CI: 0.01–0.28) for every 1 μg/m3 increase in the concentration of SO2, NO2, and PM10, respectively. These pollutants continued to have a substantial impact on the risk of incident NPC even after controlling for other ambient air pollutants. A noteworthy affirmative connection was a significant positive correlation between SO2 and NPC in male, warm season, urban areas, and elderly subgroups. In contrast to SO2, there was a significant positive correlation between PM10 and NPC in female, warm season, rural areas, non-elderly, and elderly subgroups. The association between NO2 and NPC was significantly positively correlated in male, female, rural areas, and elderly subgroups. In conclusion, our study’s findings demonstrated that exposure to airborne SO2, NO2, and PM10 can negatively impact the risk of incident NPC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ambient air pollution has been a non-negligible problem in urban areas of the world. Exposure to ambient air pollution is one of the major risk factors for global disease in the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) estimates1. The respiratory tract is one of the parts of the human body exposed to ambient air pollution and contains organs that are in direct contact with the atmosphere and affected by climate and ambient air pollution factors2,3. However, most of the previous studies on the association between ambient air pollution and respiratory cancer have focused on the lower respiratory tract organs, such as the lungs, and relatively few studies have been conducted on the upper respiratory tract4,5,6.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a malignant epithelial tumor that occurs on the top and side walls of the nasopharyngeal cavity in the upper respiratory tract. It has the characteristics of high malignancy, easy metastasis, and inconspicuous early symptoms7,8. China has the highest incidence of NPC in the world, accounting for 38.29% of the global incidence of NPC, and its incidence is significantly higher than the world average9,10. Ambient air pollution is classified as a group 1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)11. Previous studies have found that indoor air pollution is associated with an increased risk of incident NPC12,13. However, the impact of ambient air pollution on the risk of incident NPC has been relatively underexplored. Consequently, additional empirical studies are necessary to elucidate the health effects of ambient air pollution on the risk of NPC incidents in mainland China.

Hangzhou is a new first-tier city in southern China with a prosperous economy and a huge population. Due to waste gas emissions from industry and automobiles, there is also a significant level of ambient air pollution. Moreover, due to the terrain surrounded by mountains on three sides, ambient air pollutants in Hangzhou are not easy to spread, resulting in severe ambient air pollution and frequent haze weather14. NPC is rare in most parts of the world but prevalent in China, especially in southern China15,16. As well as, the data on cancer incidence in Hangzhou is also of high quality, as published by the IARC in the “Incidence of Cancer on Five Continents”17. In summary, it is an ideal city to study the impact of ambient air pollution on NPC.

We, therefore, assessed associations of ambient air pollution concentrations with the risk of incident NPC in Hangzhou using data from Hangzhou over ten years from 2013 to 2022. Differences in air pollution affect the risk of incident NPC in terms of gender, regional, age and seasonal differences are also discussed in this study.

Materials and methods

Data sources

We collected air pollution monitoring (PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, CO, and O3) data and climate monitoring data (temperature and humidity) between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2022, from national air quality control automatic monitoring stations and the Hangzhou Climate Environmental Protection Bureau. According to the WHO’s Air Quality Guidelines, we used the daily means for the other pollutants.

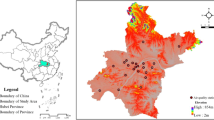

The NPC incidence data used in this study was obtained from the vital statistics system of the Hangzhou Cancer Registry and Hangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention, associate members of the IACR18,19. Through the system, we downloaded the data of all reported incident NPC cases during the study time, including the ID number, gender, age, date of birth, date of diagnosis (equal to onset) of NPC, ICD-10 encoding, and current address for each case. The date of diagnosis of NPC was the first diagnosis, and there was no prior history of NPC. Based on the data, including daily NPC incidence cases, air pollution, and climate factors, we established a time-series database. We divided the population into subgroups of different gender, ages, regions, and seasons. The gender was split into male and female based on physical characteristics; the ages were defined as elderly (age ≥ 65 years) and non-elderly (age < 65 years) according to WHO standards20; the region was divided into the rural areas and urban areas by the level of economy (Fig. 1); the season was divided into the cold season (November, January, December, January, February, March, and April) and the warm season (May, June, July, August, September, and October) according to local climatic characteristics21.

Map of Hangzhou. Note: Among these areas in Hangzhou, Tonglu County, Chun’an County, Jiande City, Fuyang District, and Lin’an District were rural areas, and the others were urban areas. (This map was created by the author, Zesheng Chen, using the software Axhub Maps at https://axhub.im/maps/.)

Statistical analysis

The generalized additive model (GAM) has been widely used to estimate the association between disease and exposure to air pollution21,22. In earlier research, the GAM was also utilized to examine the relationship between exposure to air pollution and cancer23,24. In our research, for the total population, the daily NPC incidence of residents is a small probability event, and the number of daily NPC incidence cases basically obeys the Poisson distribution. Thus, in order to investigate the relationship between exposure to SO2, NO2, and PM10 and the risk of incident NPC, the Poisson distribution-based GAM was employed. Climate factors (tempe and rhum), day of the week (DOW), public holidays (Holiday), and long-term trends (Time) were treated as controlling factors to examine relevant effects. To verify the model’s robustness, we did a sensitivity analysis: established two-pollutant models, in which PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, CO, or O3 were adjusted as confounding variables, respectively.

The single-pollutant model formula was as follows:

where E(Yt) represents the expected number of NPC incidence cases at day t; DOW and Holiday were adjusted as categorical variables; ns() indicates natural cubic spline function was used to control time, temperature, and relative humidity; α is the intercept of the equation; β is the exposure response-coefficient, which represents the log relative change in the risk of incident NPC of residents associated with one unit (1 μg/m3) increase in air pollutants; Xt represents concentration on “t” day of air pollutants; df is the degree of freedom of each parameter. We used percent change to represent the percentage increase in the risk of incident NPC of residents associated with one unit increase in air pollutants, and the formula was Percent Change (PC) = (eβ- 1) × 100%25.

In addition, we examined the model and selected the degree of freedom (df) of each variable through Akaka’s Information Criterion (AIC)26. The smaller AIC values for the time trends every year were suggestive of the preferred model. The final degree of freedom was chosen by further considering the results of sensitivity analyses. The degree of freedom of the time smoothing function is sequentially changed from 7/year to 9/year, and the time series model is respectively fitted to observe the estimated value of the effect. We used 3 degrees of freedom for both temperature and humidity and 10*7 (70) degrees of freedom for time, which has been suggested to be adequately controlled for their effects on health outcomes.

We explored the effect of different lag days of air pollutant concentration on the health effect estimation, including single-day lag effects and multi-day moving average lag effects. In our study, single-day lag includes the current day up to the previous 7 days (lag0, lag1, lag2, lag3, lag4, lag5, lag6, and lag7) and moving averages of the current and prior days (lag01, lag02, lag03, lag04, lag05, lag06, and lag07). In particular, lag0 represented the association between exposure concentration and circulatory system death on a given day, and lag01 represented 2 days moving average exposure, which was calculated as the average concentrations of the current and the previous day.

The descriptive statistics, including mean (Mean ± SD), minimum (Min), maximum (Max), and quartile (P25, Median, P75), were used to describe the data on cases of NPC incidence, air pollutants, and climate factors. Spearman correlation analysis is used to evaluate the correlation between air pollutants and climate factors because all these variables were not normally distributed. P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 were used as the criterion for the statistical significance of the correlation between factors. The differences between subgroups were examined by the following formula:

where β1 and β2 are the coefficient estimates from the model for two subgroups (e.g., male and female), SE1 and SE2 are their appropriate standard errors27,28.

The main analytical tool used in this study was the mgcv software package in R software (version 3.5.21) (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Table 1 summarizes descriptive statistics of this study on air pollutants, climate factors, and NPC incidence cases in Hangzhou from 1st January 2013 to 31st December 2022. In the 10 years of observation, a total of 3121 NPC incidence cases were in Hangzhou. Then, there was an average of 0.85 NPC incidence cases per day (SD = 1.07) and a range of 0—10 daily incidence cases. And the annual average concentration of PM10, SO2, and NO2 were 68.58 μg/m3, 11.59 μg/m3, and 40.27 μg/m3, respectively. The levels of pollutants in this study, compared with previous studies in Hangzhou, showed a slight decrease29,30. For climate factors, this study’s average daily humidity and temperature were 72.74% and 18.16℃. Regarding daily incidence, males are higher than females, non-elderly are higher than elderly, urban areas are higher than rural areas, and warm season is higher than cold season.

Table 2 shows the daily concentration of PM10 was weakly and positively correlated with SO2 (r = 0.624) and NO2 (r = 0.720) and negatively correlated with humidity (r = -0.374) and temperature (r = -0.328). The daily concentration of SO2 was correlated with NO2 (r = 0.579) and negatively correlated with humidity (r = -0.277) and temperature (r = -0.297). The humidity negatively correlated with temperature (r = -0.044).

We can see a statistically significant association between PM10, SO2, NO2, and the risk of incident NPC in Table 3. In single-pollutant models, SO2 and the risk of incident NPC were statistically significant associations at single-day lag6 (PC = 0.79%, 95% CI: 0.01–1.58%). That is, each 1 μg/m3 increase in SO2 concentration was associated with a 0.79% increase (95% CI: 0.01–1.58%) in the risk of incident NPC on lag6 day. Then PM10 and the risk of incident NPC were statistically significant associations at single-day lag0 (PC = 0.14%, 95% CI: 0.01–0.28%) and multi-day lag02 (PC = 0.17%, 95% CI: 0.00–0.34%), lag03 (PC = 0.20%, 95% CI: 0.02–0.39%), lag04 (PC = 0.23%, 95% CI: 0.03–0.42%), lag05 (PC = 0.23%, 95% CI: 0.02–0.44%), and lag06 (PC = 0.23%, 95% CI: 0.01–0.45%) in single-pollutant models. Then NO2 and the risk of incident NPC were statistically significant associations at single-day lag4 (PC = 0.36%, 95% CI: 0.03–0.69%) and multi-day lag04 (PC = 0.60%, 95% CI: 0.06–1.15%), lag05 (PC = 0.67%, 95% CI: 0.10–1.25%), and lag06 (0.61%, 95% CI: 0.01–1.20%) in single-pollutant models. We found that SO2, NO2, and PM10 were associated with an increased risk of incident NPC. We also explored the association of PM2.5, CO, and O3 with NPC but found no meaningful results (Table S2).

In Tables 4 and 5, the results of the two-pollution model show the associations between PM10, SO2, NO2, and the risk of incident NPC were still statistically significant at some lags after adjusting for other ambient air pollutants. Although the strength of the association changed, the direction of the association did not change. In particular, after adjusting the effect of PM2.5, the impact of PM10 on the risk of incident NPC increased. Therefore, the results of air pollutants affecting the risk of incident NPC in this study are robust.

Figure 2 summarizes the results of the subgroup analysis. The results show the effects between the corresponding subgroups are significantly different. The most significant effects of PM10, SO2, and NO2 were exposure related to the risk of incident NPC. Changes in PM10 concentration were associated with the daily NPC incidence in females (PC = 0.45%, 95% CI: 0.09–0.82% for lag04), warm season (PC = 0.62%, 95% CI: 0.17–1.06% for lag05), rural areas (PC = 0.34%, 95% CI: 0.11–0.58% for lag0), non-elderly (PC = 0.16%, 95% CI: 0.001–0.31% for lag0), and elderly (PC = 0.44%, 95% CI: 0.02–0.86% for lag05). The associations of SO2 exposure on the risk of incident NPC in males (PC = 1.01%, 95% CI: 0.08–1.94% for lag6), warm season (PC = 1.45%, 95% CI: 0.08–2.84% for lag5), urban area (PC = 1.14%, 95% CI: 0.20–2.10% for lag6), and elderly (PC = 1.00%, 95% CI: 0.08–1.94% for lag7) were positive statistically significant. The association between NO2 and NPC was significantly positively correlated in males (PC = 0.46%, 95% CI: 0.07–0.84% for lag5), females (PC = 1.04%, 95% CI: 0.03–2.07% for lag04), rural areas (PC = 0.64%, 95% CI: 0.02–1.25% for lag0) and elderly subgroups (PC = 1.15%, 95% CI: 0.09–2.21% for lag04).

Discussion

Few previous studies have examined the effects of exposure to SO2, NO2, and PM10 on the incidence of NPC. Our study investigated the effects of SO2, NO2, and PM10 on the risk of incident NPC in Hangzhou from 2013 to 2022. Our investigation showed variations in the relationship between SO2, NO2, and PM10 with NPC among the respective subgroups. Sensitivity to air pollutants varies between gender groups and regional groupings. The elderly are more susceptible to SO2, NO2, and PM10 impacts. Also, during the warmer months, humans are more vulnerable to SO2 and PM10.

We confirmed that the SO2, NO2, and PM10 exposure affected the risk of incident NPC, which was in line with previous studies. A combined analysis of ten large Chinese cities reveals that exposure to ambient air pollutants like SO2, PM10, and NO2 is significantly positively associated with NPC incidence31. Another longitudinal study in Taiwan, China, reported the risk of developing NPC increased with the increase in NO2 and PM2.5 exposure concentrations13. Analogous research has been carried out in the clinical setting. For instance, a clinical case–control study discovered a link between the incidence of sinus-inverted tumors and extended exposure to ambient air pollution32. The specific biological pathways underlying a potential association between air pollution exposure and NPC is unknown. A large body of evidence from indirect models suggests that inhalation of air pollutants may have significant local and systemic effects, inducing inflammation and oxidative stress, leading to aberrant cell proliferation, differentiation, and carcinogenesis33,34,35,36. One plausible mechanistic pathway is through the immune system. For example, the animal experiment observed that NO2 and SO2 inhalation induces an imbalance in the immune cells to promote an inflammatory response37,38. Another experimental study in mice similarly found increased inflammatory activity with exposure to airborne PM39. However, inflammation has been found to mediate a wide variety of diseases, including neoplasms40. It has been implicated as an etiological factor in human cancers41. This may be the biological mechanism of air pollution affecting NPC, but further animal experiments are needed to confirm it.

We observed positive statistically significant associations between SO2 and NO2 with NPC in the male subgroups and PM10 in the female subgroups. A similar conclusion was reached from a combined investigation of outdoor air pollution and lung cancer risk in seven eastern metropolises of China: men were shown to be more susceptible to SO2 and NO2 than women42. It may be related to genetic, physiological, and behavioral differences (e.g., occupation, smoking, and lifestyle) between men and women, with different sensitivities to air pollutants for different genders43. For example, one study suggested that the effects of air pollution may be stronger in nonsmokers than smokers44. The oxidative and inflammatory effects of smoking may enhance men’s susceptibility to SO2 and NO2. Anatomically, females have smaller airways than males, resulting in easier deposition of PM and more severe airway reactivity45. Additionally, this may be due to the tiny sample size of female subgroups in this study, resulting in a negative statistically significant effect of SO2 exposure on NPC in females46,47.

Similarly, the association between SO2, NO2, and PM10 with NPC was significantly positively correlated in elderly subgroups. Differences in outcomes between age subgroups can be explained from a physiological perspective. The aging body of the elderly leads to a decline in the organism’s functioning and an increased risk of various diseases, and the aging body is also more susceptible to health problems48. Previous studies have suggested that older people with weakened immune systems and chronic underlying diseases may be more sensitive to air pollution exposure than younger people49,50. Many studies have similarly found that older adults are at greater risk for air pollution-related effects51,52.

For regions, there was a significant positive correlation between PM10 and NO2 with NPC in the rural areas subgroups. The regional differences in this study may be explained by the lack of disease-management knowledge and the differences in living environments, economic levels, and medical services between urban and rural areas53,54,55. Previous studies have found that poor socioeconomic groups have increased susceptibility to air pollution due to underlying health conditions and reduced access to health care56. Not the same as PM10 and NO2, we observed positive statistically significant associations between SO2 and NPC in the urban areas subgroups. In the urban areas subgroup, the association between SO2 exposure and the risk of incident NPC may be attributed to the higher level of air pollution in urban areas than in rural areas. The primary air contaminant from motor vehicle exhaust is SO2; more motor vehicles are in urban than rural areas57,58.

Our study also noted that the association between SO2 and PM10 and the risk of incident NPC was significant in the warm season. Several possible explanations are proposed for the difference in this study in season groups. First, temperature may interact with air pollutants and affect human susceptibility to viruses, and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection is closely related to the pathogenesis of NPC59,60,61,62. Second, ambient temperature can affect air pollutants’ discharge, transport, dilution, chemical transformation, and deposition63. Moreover, in the warm season, people tend to go out more frequently than in the cold season, which exposes them to more ambient air pollutants64. However, some studies have also reported that air pollutants during the cold season lead to a higher risk of death from respiratory diseases65,66. Coal-fired emissions in the northern regions during the winter may contributed to the opposite end of the study. A study reported that northern China generally had higher coal combustion emissions than southern China because of more intense industrial emissions by thermal power generation67.In addition, the climatic and topographical characteristics of different regions may also play a role. In a study in Changsha, China, the opposite was observed in this study65. This is because Changsha has a humid subtropical monsoon climate, with northwesterly winds dominating during the cold season. The topography of Changsha is high in the south and low in the north, creating a horseshoe-shaped opening to the north where air pollutants are trapped.

There are various advantages to our study. First, this study is among the few to document the harmful impact of air pollution on the risk of incident NPC. Second, we stratified the outcomes of NPC by region, gender, age, and season. The seasonal and regional characteristics in our analysis were not taken into account in earlier research on NPC and air pollution. Lastly, to increase the reliability of our results, we used confounding factors in the model, including climate factors, time trends, DOW, and Holiday. These confounding factors may influence the frequency and amount of pollutant exposure in subjects, allowing us to overestimate or underestimate the effect of air pollution on NPC.

This study also had some limitations. This study might underestimate the effects of SO2, NO2, and PM10 on the risk of incident NPC because the data of ambient air pollutants and climate factors (obtained from fixed monitoring stations) could not represent total exposure to the population. Due to data limitations, we were unable to assess some potential modifying factors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and individual disease history. We also cannot evaluate the exact time of tumor onset, and there may be a gap between the time of NPC onset and the time of diagnosis. In addition, our analysis focuses on one city in China, so our results are limited in generalizability.

Conclusions

We discovered that exposure to SO2, NO2, and PM10 was associated with an increased risk of incident NPC. We observed that men were more sensitive to SO2 and NO2, while women were more sensitive to PM10. Elderly people might be more vulnerable to exposure to SO2, NO2, and PM10. Therefore, the protective measures for specific groups should be strengthened. In addition, we found stronger associations between SO2 and PM10 with NPC during the warm season than those observed during the cold season. The effect of PM10 and NO2 on the risk of incident NPC is more pronounced in rural areas than in urban areas. These results can provide data to support the development of policies intended to safeguard public health from air pollution, particularly in areas with high levels of air pollution.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the vital statistics system of the Hangzhou Cancer Registry and Hangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the vital statistics system of the Hangzhou Cancer Registry and Hangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Zesheng Chen should be contacted if someone wants to request the data from this study.

References

Brauer, M. et al. Ambient air pollution exposure estimation for the global burden of disease 2013. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50(1), 79–88 (2016).

Tang, J. W. & Loh, T. P. Correlations between climate factors and incidence–a contributor to RSV seasonality. Rev. Med. Virol. 24(1), 15–34 (2014).

Vandini, S. et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in infants and correlation with meteorological factors and air pollutants. Ital. J. Pediatr. 39(1), 1 (2013).

Wong, I. C., Ng, Y. K. & Lui, V. W. Cancers of the lung, head and neck on the rise: perspectives on the genotoxicity of air pollution. Chin. J. Cancer 33(10), 476–480 (2014).

Xing, D. F. et al. Spatial association between outdoor air pollution and lung cancer incidence in China. BMC Public Health 19(1), 1377 (2019).

Sapkota, A. et al. Indoor air pollution from solid fuels and risk of hypopharyngeal/laryngeal and lung cancers: a multicentric case-control study from India. Int. J. Epidemiol. 37(2), 321–328 (2008).

Kamran, S. C., Riaz, N. & Lee, N. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 24(3), 547–561 (2015).

Chua, M. L. K. et al. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet 387(10022), 1012–1024 (2016).

Chen, Y. P. et al. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet 394(10192), 64–80 (2019).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68(6), 394–424 (2018).

Loomis, D. et al. The carcinogenicity of outdoor air pollution. Lancet Oncol. 14(13), 1262–1263 (2013).

Gordon, S. B. et al. Respiratory risks from household air pollution in low and middle income countries. Lancet Respir. Med. 2(10), 823–860 (2014).

Fan, H. C. et al. Increased risk of incident nasopharyngeal carcinoma with exposure to air pollution. PLoS ONE 13(9), e0204568 (2018).

Reizer, M. & Juda-Rezler, K. Explaining the high PM(10) concentrations observed in Polish urban areas. Air Qual. Atmos Health 9, 517–531 (2016).

Yang, X., Chen, H., Sang, S., et al. Burden of all cancers along with attributable risk factors in China from 1990 to 2019: Comparison with Japan, European Union, and USA, 2296–2565 (Electronic)).

Chang, E.T. & Adami, H.O. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. 1055–9965 (Print).

2020. Cancer in Five Continents Volumes I to X. International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Wu, M. et al. Pancreatic cancer incidence and mortality trends in urban Shanghai, China from 1973 to 2017: A joinpoint regression and age-period-cohort analysis. Front Oncol. 13, 1113301 (2023).

He, Y. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in Hebei province, 2013. Medicine 96(26), e7293 (2017).

WHO. Definition of an older or elderly person. Available: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/ (2013).

Liu, C. C. et al. Short-term effect of relatively low level air pollution on outpatient visit in Shennongjia, China. Environ. Pollut. 245, 419–426 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Years of life lost from ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke related to ambient nitrogen dioxide exposure: A multicity study in China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 203(7), 111018 (2020).

Cheng, Z. et al. Air pollution and cancer daily mortality in Hangzhou, China: An ecological research. Bmj Open 14(6), e084804 (2024).

Pan, Z. et al. The influence of meteorological factors and total malignant tumor health risk in Wuhu city in the context of climate change. BMC Public Health 23(1), 346 (2023).

Jacobs, M. A. et al. Association of cumulative colorectal surgery hospital costs, readmissions, and emergency department/observation stays with insurance type. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 27(5), 965–979 (2023).

Song, G. F. et al. Blockwise AIC(c) and its consistency properties in model selection. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 50(13), 3198–3213 (2021).

Altman, D. G. & Bland, J. M. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates, 1756–1833 (Electronic)).

Xiong, Y., Yang, M., Wang, Z, et al. Association of Daily Exposure to Air Pollutants with the Risk of Tuberculosis in Xuhui District of Shanghai, China, 1660–4601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106085. LID – 6085 (Electronic)).

Cheng, Z.A.-O., Qin, K., Zhang, Y., et al. Air pollution and cancer daily mortality in Hangzhou, China: an ecological research, 2044–6055 (Electronic)).

Mo, Z., Fu, Q., Zhang, L., et al. Acute effects of air pollution on respiratory disease mortalities and outpatients in Southeastern China, 2045–2322 (Electronic)).

Yang, T. et al. Association of ambient air pollution with nasopharyngeal carcinoma incidence in ten large Chinese Cities, 2006–2013. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(6), 1824 (2020).

Mydlarz, W. K. et al. Long-term ambient air pollution exposure and risk of sinonasal inverted papilloma. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 12(9), 1200–1203 (2022).

Pitot, H. C. The molecular biology of carcinogenesis. Cancer 72(3 Suppl), 962–970 (1993).

Yang, W. & Omaye, S. T. Air pollutants, oxidative stress and human health. Mutat. Res. 674(1–2), 45–54 (2009).

Pope, C. A. 3rd. et al. Exposure to fine particulate air pollution is associated with endothelial injury and systemic inflammation. Circ. Res. 119(11), 1204–1214 (2016).

Familari, M. et al. Exposure of trophoblast cells to fine particulate matter air pollution leads to growth inhibition, inflammation and ER stress. PLoS ONE 14(7), e0218799 (2019).

Ji, X. et al. Acute nitrogen dioxide (NO2) exposure enhances airway inflammation via modulating Th1/Th2 differentiation and activating JAK-STAT pathway. Chemosphere 120, 722–728 (2015).

Zhang, Y., Ji, X., Ku, T., et al. Inflammatory response and endothelial dysfunction in the hearts of mice co-exposed to SO(2) , NO(2) , and PM(2.5), 1522–7278 (Electronic))

Happo, M.S., Salonen, R.O., Hälinen, A.I., Jalava, P.I., et al. Dose and time dependency of inflammatory responses in the mouse lung to urban air coarse, fine, and ultrafine particles from six European cities, 1091–7691 (Electronic)).

Tan, T.T. & Coussens, L.M. Humoral immunity, inflammation and cancer, 0952–7915 (Print)).

Kazbariene, B. Tumor and immunity, 1648–9144 (Electronic)).

Wang, W., Meng, L., Hu, Z., et al. The association between outdoor air pollution and lung cancer risk in seven eastern metropolises of China: Trends in 2006–2014 and sex differences, 2234–943X (Print)).

Clougherty, J. E. A growing role for gender analysis in air pollution epidemiology. Environ. Health Perspect. 118(2), 167–176 (2010).

Künzli, N., Jerrett, M., Mack, W. J., Beckerman, B., et al. Ambient air pollution and atherosclerosis in Los Angeles, 0091–6765 (Print)).

Kan, H., London, S. J., Chen, G., Zhang, Y., et al. Season, sex, age, and education as modifiers of the effects of outdoor air pollution on daily mortality in Shanghai, China: The Public Health and Air Pollution in Asia (PAPA) Study, 0091–6765 (Print)).

Peterson, S. J. & Foley, S. Clinician’s guide to understanding effect size, alpha level, power, and sample size. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 36(3), 598–605 (2021).

Chung, K. C. et al. The prevalence of negative studies with inadequate statistical power: an analysis of the plastic surgery literature. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 109(1), 1–6 (2002) (discussion 7-8).

Newman, A. B. & Ferrucci, L. Call for papers: aging versus disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64(11), 1163–1164 (2009).

Domingo, J. L. & Rovira, J. Effects of air pollutants on the transmission and severity of respiratory viral infections. Environ. Res. 187, 109650 (2020).

Conticini, E., Frediani, B. & Caro, D. Can atmospheric pollution be considered a co-factor in extremely high level of SARS-CoV-2 lethality in Northern Italy?. Environ. Pollut. 261, 114465 (2020).

Kan, H. et al. Season, sex, age, and education as modifiers of the effects of outdoor air pollution on daily mortality in Shanghai, China: The Public Health and Air Pollution in Asia (PAPA) Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 116(9), 1183–1188 (2008).

Liu, C. S. et al. Long-term association of air pollution and incidence of lung cancer among older Americans: A national study in the Medicare cohort. Environ. Int. 181, 108266 (2023).

Franco, G. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, behavior, and practices of self-breast examination in Jalisco, Mexico. J. Cancer Educ. 37(5), 1433–1437 (2022).

Gou, A. et al. Urban-rural difference in the lagged effects of PM2.5 and PM10 on COPD mortality in Chongqing, China. BMC Public Health 23(1), 1270 (2023).

Fairburn, J. et al. Social inequalities in exposure to ambient air pollution: A systematic review in the WHO European Region. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16(17), 3127 (2019).

Lipfert, F. W. Air pollution and poverty: does the sword cut both ways?. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 58(1), 2–3 (2004).

Yang, Y. et al. Study on the concentration retrieval of SO(2) and NO(2) in mixed gases based on the improved DOAS method. RSC Adv. 13(28), 19149–19157 (2023).

Prietsch, W. On air pollution caused by motor vehicle exhausts in cities and areas of large industrial concentrations. Survey of the current situation. Z. Gesamte Hyg. 13(5), 326–333 (1967).

Young, L. S., Yap, L. F. & Murray, P. G. Epstein-Barr virus: more than 50 years old and still providing surprises. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16(12), 789–802 (2016).

Zhu, Q. Y. et al. Advances in pathogenesis and precision medicine for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. MedComm (2020) 2(2), 175–206 (2021).

Tsang, C. M. & Tsao, S. W. The role of Epstein-Barr virus infection in the pathogenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Virol. Sin. 30(2), 107–121 (2015).

Lin, C. T. Relationship between Epstein-Barr virus infection and nasopharyngeal carcinoma pathogenesis. Ai Zheng 28(8), 791–804 (2009).

Macdonald, R. W., Harner, T. & Fyfe, J. Recent climate change in the Arctic and its impact on contaminant pathways and interpretation of temporal trend data. Sci. Total Environ. 342(1–3), 5–86 (2005).

Tian, Y. et al. Short-term effects of ambient fine particulate matter pollution on hospital visits for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Beijing, China. Environ. Health 17(1), 21 (2018).

Feng, Q., Chen, Y., Su, S., et al. Acute effect of fine particulate matter and respiratory mortality in Changsha, China: A time-series analysis, 1471–2466 (Electronic)).

Zhang, W., Ling, J., Zhang, R., et al. Short-term effects of air pollution on hospitalization for acute lower respiratory infections in children: A time-series analysis study from Lanzhou, China, 1471–2458 (Electronic)).

Yin, P., Brauer, M., Cohen, A., et al. Long-term fine particulate matter exposure and nonaccidental and cause-specific mortality in a large National Cohort of Chinese Men, 1552–9924 (Electronic)).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the cancer data collection staff at the Hangzhou Tumor Registry and the Hangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention.The authors sincerely thank all the authors of this article for their contribution to the completion of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zesheng Chen: Software, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization; Jue Xu: Validation, Data curation, Writing—review & editing, Formal analysis; Caixia Jiang: Supervision, Project administration; Zhecong Yu and Kang Qin: Data curation, Project administration; Zongxue Cheng and Yaoyao Wu: Software, Visualization. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Cheng, Z., Wu, Y. et al. The association between ambient air pollution and the risk of incident nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Hangzhou, China. Sci Rep 14, 31887 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83388-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83388-2