Abstract

Nanoscale Fourier transform infrared (Nano-FTIR) imaging and spectroscopy correlated with photoluminescence measurements of lunar Apollo samples with different surface radiation exposure histories reveal distinct physical and chemical differences associated with space weathering effects. Analysis of two sample fragments: an ilmenite basalt (12016) and an impact melt breccia (15445) show evidence of intrinsic or delivered Nd3+ and an amorphous silica glass component on exterior surfaces, whereas intrinsic Cr3+ and/or trapped electron states are limited to interior surfaces. Spatially localized 1050 cm−1/935 cm−1 band ratios in Nano-FTIR hyperspectral maps may further reflect impact-induced shock nanostructures, while shifts in silicate band positions indicate accumulated radiation damage at the nanoscale from prolonged space weathering due to micrometeorites, solar wind, energetic x-rays and cosmic ray bombardment. Our observations demonstrate that space weathering alterations of the surface of lunar samples at the nanoscale may provide a mechanism to distinguish lunar samples of variable surface exposure age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Lunar regolith samples returned by the Apollo missions have been the subject of extensive laboratory analyses and evidence of space weathering is well-documented in both remote sensing and in-situ analysis of lunar samples down to the nanoscale. Nano-scale evidence for space weathering primarily includes structural defects (e.g. heavy ion particle tracks), amorphous rims of otherwise crystalline minerals, trapped He and H and nanophase Fe1,2,3,4. At larger micro- and meso- scales, the presence of melt breccias and high-pressure mineral polymorphs are further evidence of shock metamorphism by meteorite impacts. Nano-scale space weathering has been simulated in the laboratory using laser, ion, electron, and x-ray irradiation of lunar simulants5,6,7, and the effects have been probed on meteorites and returned lunar samples using scanning electron microscopy (SEM)8,9, transmission electron microscopy (TEM)5, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)10, photoluminescence (PL), cathodoluminescence (CL)11, and IR absorption/reflection spectroscopy11,12, with the latter method being most directly comparable to orbital fly-by spectroscopic campaigns13,14.

Over the nearly five decades since the Apollo landings, technological advances have allowed laboratory investigations to be extended to nanometer spatial resolutions, using techniques such as atom probe tomography/desorption and nano-secondary ion mass spectroscopy (NanoSIMS)15. Though optical spectroscopy techniques can now be carried out with nanoscale spatial resolution16,17,18,19, most spatially resolved studies are restricted by a diffraction-limited spectral resolution, mostly in the mid-IR2,11,14,20. Typically, these optical measurements focus on the Christiansen feature (CF) and Reststrahlen bands (RB) which appear in the ~ 650–4000 cm−1 (2.5–15 μm) region.

This work presents a correlative nanoscale Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (Nano-FTIR), photoluminescence, and spatially resolved hyperspectral imaging study of micron-sized flakes from both external (outward or solar wind-facing) and internal (center facing) portions of two Apollo lunar samples: an ilmenite basalt (sample 12016) and impact melt breccia (sample 15445). Combining atomic force microscopy (AFM) imaging along with near-field and photoluminescent (PL) spectroscopy techniques allows for sample characterization at a ∼10 nm spatial scale while co-resolving variations in topography, mineral structure, and trace heavy element composition, though studies of the latter were restricted to diffraction-limited PL. This approach can synergistically reveal localized physical and chemical alterations from space weathering that may not be visible using conventional micro- or macro-scale optical approaches.

Lunar samples were chosen from two sites with different surface exposure histories. The Apollo 12 parent sample 12016 is a medium-size olivine basalt with glass-lined micrometeorite pits on the exterior surface21. A crystallization age of 12016 has not been determined, but the highly impacted and processed surface suggests an extended exposure at the lunar surface. The Apollo 15 parent sample 15445 is a recrystallized impact melt breccia containing norite and spinel troctolite clasts embedded in a glassy matrix with fragmented and recrystallized plagioclase, olivine, and opaque minerals21. The sample has 147Sm-143Nd isochron ages of 4.46 and 4.28 Ga22,23 and a 81Kr surface exposure age of 157 ± 22 Myr21.

Subsample 12016.48 is a 1 mm thick slice collected from an exterior surface of the parent sample. Two separate sample flakes were taken from the front and back of the 12016.48 slice, denoted side 1 and side 2. Due to the nature of the flake collection, and preparation, it was not possible to state with certainty whether Side 1 or Side 2 faced outward. Subsample 12016.49 is a 1 mm thick slice taken from the rock interior, as such all analyzed 12016.49 subsamples are classified as inward facing. Similarly, subsample 15445.307 was a 1 mm thick slice taken from the exterior of sample 15445, and 15445.311 was a 1 mm thick slice taken from the interior. Flakes were also taken from terrestrial analog samples of anorthite, albite, San Carlos forsterite, and enstatite for analytical comparison to the lunar samples (see supplementary section for the terrestrial mineral history and sources).

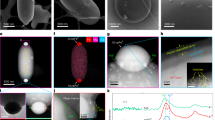

An overview of the AFM, PL and Nano-FTIR techniques and representative data is given in Fig. 1a–g (see methods for additional details). Figure 1a shows an optical image of the flake taken from sample 15445.311 and studied using the experimental setup (shown in Fig. 1d). The topographical map of a small region on the flake is shown in Fig. 1b, and a spatially-correlated near-field FTIR amplitude image taken using an infrared laser frequency of 932 cm−1 is shown in Fig. 1e. Representative PL (Fig. 1c) and 2nd harmonic Nano-FTIR (Fig. 1f and g) spectra are shown on the left and right sides, respectively. The colored dots in the topography and amplitude images are within a spatial error of 0.3 μm and denote the position where the spectra shown in Fig. 1c, f, and g were obtained.

Nano-FTIR and PL schematic and example results for sample 15445.311. (a) Optical image of a flake from the 15445.311 sample on a SiO2 substrate, (b) Topographical image of a 12 μm × 7 μm region of the sample, (c) PL spectra at various probe sites on 15445.311, (d) Schematic experimental set-up for PL (left) and Nano-FTIR (right) from the AFM probe of the lunar sample (center), (e) Near-field amplitude image, (f) Nano-FTIR amplitude spectra, (g) Nano-FTIR phase spectra (PM = parabolic mirror, NF = neutral density filter, L = lens, BS = beam splitter, VM = vibrating mirror).

PL spectra taken on the lunar samples using a single wavelength excitation laser (λ = 532 nm) are shown in Fig. 2a. A strong broad peak at around 650–680 nm is present in 12016.48 (sides 1 and 2). A weak broad peak between 675 and 725 nm is observed in 12016.49 followed by a stronger feature peaking between 870 and 880 nm. Samples 15445.307 and 15445.311 have a broad feature peaking at 675 nm and a sharper peak centered at 875 nm only observed in 15445.307. Note this peak width may extend to longer wavelength since the instrumental PL cut-off is 920 nm. The terrestrial albite, anorthite, forsterite, and enstatite samples show broad features that peak near 630, 710, 630, and 645 nm, respectively (see supplementary Figure S1). Least squares spectral fits of the lunar samples using these terrestrial sample spectral profiles are shown as red lines in Fig. 2a. The fits were carried out by numerically summing weighted measured contributions of terrestrial samples yielding empirical mineralogical compositions. All these fits are dominated by appreciable contributions of anorthite and forsterite except for 12016.48 side 2, which can be explained by enstatite and anorthite (see supplemental Figures S2–S6).

(a) PL and (b) Nano-FTIR amplitude and (c) phase spectra of the indicated lunar samples (black curves). Fits (see supplemental for details) to terrestrial sample spectra are shown by the red curves. The feature at 1150 cm−1 shown by the arrow in (b) (top panel) is not present in any of the terrestrial samples. Nano-FTIR simulation of amorphous SiO2 (dark yellow dotted line) reproduces the 1150 cm−1 amplitude and phase features as well as a Nano-FTIR measurement (blue) of amorphous SiO224. The SiO2 phase peak is slightly shifted in the simulation and better represented by the SiO2 measurement. Yellow and green vertical bands indicate the expected range of the CF and RB features.

These lunar samples are unlikely to have pure anorthite, forsterite or enstatite (the latter with Mg/Fe + Mg close to 0.9 or less) and terrestrial minerals are known to have compositional variability and intrinsic ions that give rise to photoluminescence. The PL spectra of the lunar samples can be understood qualitatively with respect to the trace metals and photoactive ions present in the terrestrial samples. Specifically, the broad peak around 675–680 nm (extending from 625 to 750 nm) in 12016.48 (sides 1 and 2) and 15445.311 can be attributed to the incorporation of Mn2+, Fe3+, and Mg2+25,26. The split features peaking at 850 and 875 nm in 12016.49 are not seen on any of the terrestrial mineral samples and may be due to Cr3+ and Nd3+, respectively. The sharper peak centered at 875 nm in 15445.307 may also be attributed, at least partially, to Nd3+25. Trace metal species such as Cr and Nd can be intrinsic (e.g. 143Nd is a stable daughter product from the radiogenic decay of 147Sm27) or delivered by meteorite impactors on the lunar surface. The relative ratios of the Cr3+ and Nd3+ observed in 12016.49 and 15445.307 are consistent with the amounts measured in the parent Apollo samples18. Unfortunately, limited knowledge of PL emission strengths25 and orientation effects, which are likely minimal at the PL focal spot scale, precludes determination of both absolute and relative abundances.

The features that peak near 875 nm may reflect lunar geochemistry, or alternatively may be associated with the effects of space weathering. Specifically, the 875 nm band may be a radiation-induced electron (hole) trap state(s) produced by solar wind, X-ray or cosmic ray exposure. Solar wind (protons, electrons and soft X-rays) have penetration depths < 100 nm in regolith whereas higher energy (> 10 keV) X-rays penetrate up to several mm and galactic cosmic rays from centimeters to meters depending on the density.

In a luminescence microscopy study of terrestrial feldspar by Kumar et al.28, two peaks appear near 880 nm and 955 nm in PL, but shifted down to 750 nm in cathodoluminescence. These were produced by X-ray and high energy electron irradiation, respectively. These electron trap states are thought to be useful in luminescence geochronology as faithful records of radiation dosage since they are stable states that do not bleach nor anneal over time28,29. The 875 nm PL band in the inward-facing sample 12016.49 can be fit well using a substantial contribution of the electron trap state spectra derived from Kumar et. al 28. In contrast, the outward facing sample 15445.307 is best fit with Nd3+ emission with a much smaller electron trap state contribution (See Figures S4 and S5). This implies the trap states are likely made from the more deeply penetrating X-rays or cosmic rays, and that the Nd3+ has either migrated to the surface or was delivered by an impact event in the near vicinity. Overall, the PL data can be explained by a combination of compositional variability and possible defect and electron (hole) trap sites formed by space weathering.

Since differences between lunar and terrestrial spectra are expected due to space weathering effects, systematic Nano-FTIR studies can help elucidate the radiation effects on the crystalline structure and optical spectra. To illustrate this, normalized near-field amplitude and phase spectra obtained using Nano-FTIR spectroscopy of the lunar samples over the 675 -1300 cm−1 range are shown in Fig. 2b and c, respectively. There is an inherent correlation between a sample’s amplitude and phase spectra to its reflectivity and absorption, respectively, both of which are probed locally in the near field and described by the extended dipole model. These spectra therefore enable discrimination of compositional heterogeneities at nanoscale spatial resolution through analysis of peak and trough locations and intensities30. The closest matching Nano-FTIR terrestrial mineral spectra (see supplementary Figure S1) compared to the lunar spectra are shown in red lines (Fig. 2b and c). The yellow and green vertical bands indicate the expected range of the CF and RBs, respectively. The CF is a reflectance minimum, located around 1250–1000 cm−1 (8–10 µm) in most silicates and the RBs are strong fundamental molecular vibrations that occur at < 1250–1000 cm−1 and correspond to Si–O asymmetric stretching and O–Si–O bending modes31,32,33,34. As found from the PL fits, anorthite can approximately account for the Nano-FTIR lunar spectra, except for 12016.48 side 2 and 12016.49 which are more closely reproduced by enstatite and forsterite, respectively. It should be noted that the diffraction-limited PL samples spatial regions of ~ 300 nm × 300 nm which may include a mixed mineralogy, unlike the Nano-FTIR whose optical sampling zone is smaller than a typical grain.

A significant discrepancy seen only in the lunar samples is the strong amplitude peak near 1150 cm−1 (shown by the arrow in Fig. 2b top panel). This band, which is also present but weaker in the phase spectra, is prominent in 12016.48 side 1 and not present in side 2. This is potential evidence that side 1 was an outward facing exterior subsample, while side 2 was inward facing. A similar band is observed as a weaker feature in samples 15445.307 and 15445.311, two impact melt breccia samples. To understand this, we simulated (see methods section) the near-field spectra of an amorphous silica band which is shown as a dark yellow dotted line. This reproduces the 1150 cm−1 feature well allowing for a nearly complete reproduction of the three lunar amplitude and phase spectra. To further illustrate this, comparison to a Nano-FTIR spectra of an amorphous silica sample is also shown in blue24. The SiO2 phase peak is slightly shifted in the simulation due to approximations35 and better represented by the amorphous SiO2 measurement.

Amorphous silica rims can be made by micrometeorite impacts or solar wind irradiation. If this amorphous silica band was formed from space weathering, the strong distinction between spectra from each side of 12016.48 is consistent with a prolonged surface exposure history of the sample, while the less pronounced 1150 cm−1 feature in sample 15445 may be explained by inclusion of previously exposed fragments into the melt breccia.

The Nano-FTIR spectra shown in Fig. 1f and g are similar at each point measured on the 15445.311 interior sample surface, but the amplitude and phase at any given wavenumber differ with variable deviancy between spectra. To elucidate the potential nanoscale heterogeneity inherent in space weathered lunar samples, we employed single frequency scattering near-field optical microscopy (s-SNOM) and Nano-FTIR point spectroscopy at distinct points on the 15445.307 exterior sample surface. Note that the 15445.307 subsample at which the image and spectra were captured for the data presented in Fig. 3 is different from the 15445.307 subsample used for the data shown in Fig. 2. The clear contrast distinctions seen in the topographical image (Fig. 3a) are faithfully captured in the point spectra spanning the spectral range of 800–1200 cm−1 that were acquired in the regions denoted by the red[R] and blue[B] squares and lines (Fig. 3a and b). The image contrast is also seen clearly in the single-frequency amplitude and phase maps collected at 932 cm−1 (Fig. 3c and d) and 1050 cm−1 (Fig. 3e and f). The contrast between these datasets stem from variations in the surface dielectric constants that may be caused by shock metamorphism from meteorite impacts and it is more discernible at the 1050 cm−1 frequency.

Topographical, Nano-FTIR images, and spectra of lunar sample 15445.307. (a) Topographical image. (b) Nano-FTIR amplitude and phase spectra at locations (red[R] and blue[B] squares) in the image (a). (c) Amplitude map at 932 cm−1. (d) Phase map at 932 cm−1. (e) and (f), same as (c) and (d) but at 1050 cm−1. Each image corresponds to a spatial scale of 1000 nm × 1000 nm.

To further explore possible effects of shock metamorphism, Fig. 4 displays topography (Fig. 4a), amplitude and height profiles (Fig. 4b), and single frequency Nano-FTIR amplitude maps at 935 cm−1 (Fig. 4c) and 1050 cm−1 (Fig. 4d) for the 15445.307 subsample, similar to those shown in Fig. 3, but at a different location (See Figure S7 for corresponding Nano-FTIR phase maps). The amplitude and topography variations shown in Fig. 4b correspond to the dashed horizontal line in Fig. 4a, c, and d. These profiles suggest there is no clear correlation between structures in the topography and the amplitude variations, such that amplitude variations can be interpreted to reflect changes in surface chemistry.

(a) Topographical image of lunar sample 15445.307. (b) Amplitude and topographical profile curves corresponding to the dashed line in (a), (c), and (d). Amplitude images corresponding to (a) at (c) 935 cm−1[B] and (d) 1050 cm−1[R]. (e) Nano-FTIR amplitude ratio 1050 cm−1/935 cm−1 versus 935 cm−1 for 15445.307 (upper frame) and 15445.311 (lower frame) binned according to the reflectance ratios for shocked-induced pressure proposed by Martin36. (f) Spatial locations of the 25–45 GPa bin and > 45 GPa bin pixels in 15445.307 (upper frame) and 15445.311 (lower frame).

The frequencies chosen here (935 cm−1 and 1050 cm−1) are very close to those adopted by Martin et al.36. (932 cm−1 and 1064 cm−1) as potential diagnostics of shock effects in feldspars. These frequencies are referred to in the literature as Reststrahlen Band (RB) RB3 and RB1, respectively. The 932 cm−1 band is the dominant Si–O stretch peak and is present in all phases (mineral or glass). The 1064 cm−1 band is the point of largest percent reflectance variation within the RB region of the spectrum. Martin et al. argue that the intensity of the reflectance ratio 1064 cm−1/932 cm−1 can be used as an indicator of shock induced pressure with rough binning of < 20 GPa (< 0.42), 20–45 GPa (0.42–0.75,) and > 45 GPa (> 0.75). This contention is based on far-field FTIR spectroscopy of grouped lunar Miller Range meteorites compared to terrestrial anorthite and maskelynite samples. A similar relationship may also exist for near-field measurements of weathered lunar samples.

Adopting the approach of Ref.36, Fig. 4e (upper frame) plots the Nano-FTIR amplitude for 935 cm−1 versus the 1050 cm−1/935 cm−1 ratio for an expanded region (2000 nm × 2000 nm) of sample 15445.307 (see supplementary Fig. S8 for the full topographical image). This corresponds to 6400 pixels each with a nominal area of 25 nm × 25 nm. For most of the sample, the 1050 cm−1/935 cm−1 ratios range from ~ 0.2–0.4, but approaches or exceeds 1.0 in certain regions. Figure 4f (upper frame) plots the spatial coordinates of the points for the 25–45 GPa and > 45 GPa bins which are shown to primarily reside along a horizontal line with the higher-pressure points more tightly clustered. Conversely, the same analysis performed for 15445.311 suggests pressures of 25–45 GPa across most of the 2000 nm × 2000 nm section of the sample as illustrated in Fig. 4e and f (lower frames). Similar plots for the Nano-FTIR phase are given in the supplemental Fig. S9. Linear regions of > 45 GPa band ratios may reflect spatial localization of shock-induced impact melting along nano-scale fractures or veins37. Semi-parallel planar fractures and veins have been observed in a variety of shocked silicate and phosphate minerals38,39,40,41, and the spatially localized damage zones observed in both flakes is consistent with an interpretation of sample 15445 as an impact melt shocked breccia.

Variations in RB1 and RB3 ratios similar to those reported here were observed by Stojic et al.42 with micro-FTIR spectroscopy of laboratory shocked olivine powders. However, Stojic et al.42. suggests that the shock pressure effects measured by Martin et al.36 may also be due to mixed crystalline orientations. While mixed crystal orientations may contribute to the variations in the RB bands observed here, the 10 nm × 10 nm spatial resolution of the current Nano-FTIR measurements may rule out this alternative explanation or at least minimize the effects since the optical sampling zone is small compared to any grain or crystallite size. The highly heterogeneous features and high-pressure zones observed over nanoscale distances are consistent with localized shock fronts and clustered lattice damage involving meteorite bombardment. Ionization tracks (i.e. radioactive decay by alpha ejection or spontaneous fission) can produce abrupt linear features at the nano-scale but these would typically be in-situ and within the mineral.

Correlated photoluminescence (PL), nanoscale Fourier transform infrared (Nano-FTIR) spectroscopy and nano-scale topographical imaging have been used to characterize ∼1 μm thick flakes extracted from exterior and interior faces of Apollo lunar samples 12016 and 15445. The broad 650–675 nm peak in the PL spectra is consistent with an anorthite mineralogy for most measurements, with others better explained by the chemical compositions typically found in forsterite or enstatite. The 700–800 nm feature on the 12016.48 interior flake correlates with Cr3+ and the 800–900 nm feature is likely dominated by X-ray or cosmic ray induced electron-trap states with potentially limited contributions from intrinsic or delivered Nd3+. In contrast, the 800–900 nm emission band observed from the 15445.307 exterior flake appears to be dominated by intrinsic or delivered Nd3+ with limited radiation induced electron-trap state contributions. The spatially localized 1050 cm−1/935 cm−1 band ratios observed in the Nano-FTIR and hyperspectral maps may correlate with localized shock features in both 15445.311 and 15445.307, consistent with interpretation of the sample as an impact melt breccia. For 12016.48, the observed 1150 cm−1 feature can be explained by an amorphous glass coating likely produced by space weathering processes like micrometeorite impacts or solar wind induced lattice damage. These unique non-destructive table-top measurements provide a new opportunity to identify and distinguish lunar sample surfaces with prolonged surface exposure histories. Moreover, the potential identification of stable electron-trap states suggests that selective photoluminescence measurements may provide additional geochronological constraints to enhance cosmogenic nuclide-based techniques to measuring lunar surface exposure ages. In conclusion, nanoscale observation of lunar samples is a new frontier to unravel the details of space weathering and other processes controlling the evolution of the lunar surface.

Methods

Experimental approach

Flakes of the lunar samples 15445.311, 15445.307, 12016.48, and 12016.49 were extracted from cut (approximately 5 × 1 mm) slabs and deposited onto silicon (Si) substrates for mapping and characterization. Flakes of terrestrial samples including enstatite, anorthite, forsterite, and albite were similarly extracted from bulk samples and deposited for comparative analysis with lunar samples.

A commercial (Attocube co.) scattering type scanning near-field microscope (s-SNOM) that is based on a tapping mode AFM was utilized to perform the near-field imaging of the lunar sample. The Nano-FTIR data were acquired using a combination of s-SNOM and a broad-band infrared light source. Tapping mode AFM uses a cantilevered metal coated tip oscillating at a resonant frequency of 280 kHz and a tapping amplitude of 50 nm. A broad-band IR beam with a frequency range of 700–2100 cm−1 was focused to the tip using a parabolic mirror. Near-field signal containing material specific information was then backscattered and detected by an asymmetric Fourier transform Michelson interferometer. The system operates with pseudoheterodyne detection using a singular beam splitter and moving mirror model. In order to ensure the near-field information was not contaminated by background artifacts, the detector signal was demodulated at a higher harmonic n of the tip mechanical resonance frequency. The amplitude and phase IR near-field spectra were normalized by collecting reference spectrum from an area on the Si substrate used to hold the sample flakes and then taking spectra at the appropriate sample locations. Diffraction-limited PL spectra were also collected using the same setup under ambient conditions. To normalize the spectra, a reference spectrum was taken on the Si substrate.

The Nano-FTIR tip size resulted in a typical spatial resolution of 10 × 10 nm. Each spectrum acquisition time was 10 s and was averaged over 5 individual acquisitions of each spectrum, for a total of 50 s. Lunar samples had from 20–30 individual spectrum taken at each wavenumber range. Terrestrial samples generally had less than 10.

Simulation

To simulate the measured Nano-FTIR amplitude and phase spectra of the lunar samples, we apply the extended dipole model for the probe tip interacting with three layers (air, sample, and substrate)24,30. Incorporating known dielectric function data for the sample and silicon substrate (properties obtained from far-field measurements or calculations), the normalized s-SNOM amplitude S2 and phase φ2 for the second-harmonic are computed. Figure 2b and c give the computed Nano-FTIR amplitude and phase for an amorphous silicate sample and Figure S10 gives an example for crystalline enstatite. The simulation approach allows for utilization of the extensive literature on measured mineralogical optical constants and dielectric functions. For the simulated amorphous silicate amplitude and phase spectra, the optical constants of Ref.43. were adopted. The spectral peaks that are experimentally acquired in Nano-FTIR amplitude and phase spectra exhibit a shift towards the blue end of the spectrum when compared to the real and imaginary optical constants. While there are similarities in the overall behavior of the spectra, care must be taken in interpretation. Hence, quantitative interpretation of s-SNOM spectra of astro-minerals requires simulation or direct s-SNOM measurements of reference mineral samples44.

Data availability

Datasets are available at https://hdl.handle.net/1853/65559 or upon request with the corresponding author.

References

Denevi, B. W. et al. Space weathering at the moon. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 89, 611–650. https://doi.org/10.2138/rmg.2023.89.14 (2023).

Pieters, C. M. & Noble, S. K. Space weathering on airless bodies. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 121, 1865–1884. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JE005128 (2016).

Cymes, B. A., Burgess, K. D. & Stroud, R. M. Helium reservoirs in iron nanoparticles on the lunar surface. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 189. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01349-z (2024).

Burgess, K. D., Cymes, B. A. & Stroud, R. M. Hydrogen-bearing vesicles in space weathered lunar calcium-phosphates. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 414. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01060-5 (2023).

Chrbolkova, K. et al. Comparison of space weathering spectral changes induced by solar wind and micrometeoroid impacts using ion- and femtosecond-laser-irradiated olivine and pyroxene. Astron. Astrophys. 654, A143. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202140372 (2021).

Andreas, M. et al. Mid-infrared spectroscopy of laser-produced basalt melts for remote sensing application. Icarus 335, 113410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2019.113410 (2020).

Bennett, C. J., Pirim, C. & Orlando, T. M. Space-weathering of solar system bodies: A laboratory perspective. Chem. Rev. 113, 9086–9150. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr400153k (2013).

Gopon, P. et al. Ultra-reduced phases in Apollo 16 regolith: Combined field emission electron probe microanalysis and atom probe tomography of submicron Fe-Si grains in Apollo 16 sample 61500. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 52, 1941–1962. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.12899 (2017).

Gu, L. et al. Space weathering of the Chang’e-5 lunar sample from a mid-high latitude region on the moon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e97875. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022gl097875 (2022).

Yu, P. D., Ivanov, A. V., Wlotzka, F., Galimov, E. M. & Wänke, H. High enrichment of carbon and volatile elements in the surface layers of Luna 16 soil sample 1635: Result of comet or meteorite impact?. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 155, 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(97)00212-4 (1998).

Pernet-Fisher, J., Joy, K., Martin, D. & Donaldson Hanna, K. Assessing the shock state of the lunar highlands: Implications for the petrogenesis and chronology of crustal anorthosites. Sci. Rep. 7(5888), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72334-7 (2017).

Donaldson Hanna, K. L, et al. Effects of varying environmental conditions on emissivity spectra of bulk lunar soils: Application to Diviner thermal infrared observations of the Moon. Icarus 283, 326–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2016.05.034 (2017).

Lucey, P. G. et al. Space weathering effects in Diviner Lunar Radiometer multispectral infrared measurements of the lunar Christiansen Feature: Characteristics and mitigation. Icarus 283, 343–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2016.05.010 (2017).

Wu, Y. and Hapke, B., Spectroscopic observations of the Moon at the lunar surface. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 484, 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2017.12.003 (2018).

Zhou, C. et al. Chang’E-5 samples reveal high water content in lunar minerals. Nat. Commun. 13, 5336. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33095-1 (2022).

Utt, K. L., Ogliore, R. C., Bechtel, H. A., Gillis-Davis, J. J. & Jolliff, B. L. Detecting sub-micron space weathering effects in lunar grains with synchrotron infrared nanospectroscopy. J. Geophys. Res-Planet 126, e2021JE006921. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JE006921 (2021).

Dominguez, G. et al. Nanoscale infrared spectroscopy as a non-destructive probe of extraterrestrial samples. Nat. Commun. 5, 5445. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6445 (2014).

Yesiltas, M. et al. Biconical reflectance, micro-Raman, and nano-FTIR spectroscopy of the Didim (H3–5) meteorite: Chemical content and molecular variations. Meteorit. Planetary Sci. 55, 2404–2421 (2020).

Young, J. M. et al. Nano-FTIR investigation of the CM Chondrite Allan Hills 83100. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 127, e2021JE007166. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JE007166 (2022).

Pieters, C. M., Fischer, E. M., Rode, O. & Basu, A. Optical effects of space weathering–the role of the finest fraction. J. Geophys. Res-Planet 98, 20817–20824. https://doi.org/10.1029/93je02467 (1993).

Meyer, C. The Lunar Sample Compendium, Articles 12016, 15445 https://curator.jsc.nasa.gov/lunar/lsc/ (2023).

Shih, C. et al. Ages of pristine noritic clasts from Lunar Breccia-15445 and Breccia-15455. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac 57, 915–931. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(93)90178-Y (1993).

Drozd, R. J., Kennedy, B. M., Morgan, C. J., Podosek, F. A. & Taylor, G. J. The excess fission xenon problem in lunar samples. Lunar Planetary Sci. Con. Proc. 1, 599–623 (1976).

Fali, A. et al. Nanoscale spectroscopy of dielectric properties of mica. Acs Photonics 8, 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.0c00951 (2021).

Gaft, M., Panczer, G. & Reisfeld, R. in Springer Mineralogy, 1 online resource (XIX, 606 pages 431 illustrations, 201 illustrations in color (Springer International Publishing : Imprint: Springer,, Cham, 2015).

Moriarty, D. P. & Pieters, C. M. Complexities in pyroxene compositions derived from absorption band centers: Examples from Apollo samples, HED meteorites, synthetic pure pyroxenes, and remote sensing data. Meteoritics Planetary Sci. 51, 207–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.12588 (2016).

Fu, X. H., Zou, Y. L. & Ouyang, Z. Y. REE characteristics and Nd isotopic compositions of Lunar pristine rocks: Implications for petrogenesis of pristine rocks and source regions. Acta Geochim. 29, 326–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11631-010-0464-4 (2010).

Kumar, R. et al. Site-selective mapping of metastable states using electron-beam induced luminescence microscopy. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72334-7 (2020).

Prasad, A. K., Poolton, N. R. J., Kook, M. & Jain, M. Optical dating in a new light: A direct, non-destructive probe of trapped electrons. Sci. Rep. 7, 12097. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10174-8 (2017).

Govyadinov, A. A., Amenabar, I., Huth, F., Carney, P. S. & Hillenbrand, R. Quantitative measurement of local infrared absorption and dielectric function with tip-enhanced near-field microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 1526–1531. https://doi.org/10.1021/jz400453r (2013).

Hunt, G. R., Salisbury, J. & Lenhoff, C. Visible and near infrared spectra of minerals and rocks. I Silicates. Modern Geol. 2, 23 (1973).

Glotch, T. et al. Near-field infrared spectroscopy as a tool for analysis of Chondritic returned samples. Asteroid Sci. Age Hayabusa2 OSIRIS-Rex 2189, 2061 (2019).

Yesiltas, M., Glotch, T. D. & Sava, B. Nano-FTIR spectroscopic identification of prebiotic carbonyl compounds in Dominion Range 08006 carbonaceous chondrite. Sci. Rep. 11, 11656. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91200-8 (2021).

Yesiltas, M., Glotch, T. D. & Kaya, M. Nanoscale infrared characterization of dark clasts and fine-grained rims in CM2 chondrites: Aguas Zarcas and Jbilet Winselwan. ACS Earth Space Chem. 5, 3281–3296. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.1c00290 (2021).

Mester, L., Govyadinov, A. A., Chen, S., Goikoetxea, M. & Hillenbrand, R. Subsurface chemical nanoidentification by nano-FTIR spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 11, 3359. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17034-6 (2020).

Martin, D. J. et al. Investigating the shock histories of lunar meteorites Miller Range 090034, 090070, and 090075 using petrography, geochemistry, and micro-FTIR spectroscopy. Meteorit. Planetary Sci. 52, 1103–1124. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.12860 (2017).

Walton, E. L., Sharp, T. G. & Hu, J. Frictional melting processes and the generation of shock veins in terrestrial impact structures: Evidence from the Steen River impact structure, Alberta, Canada. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac 180, 256–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2016.02.024 (2016).

Xiande, X., Ming, C., Deqiang, W. & El Goresy, A. NaAlSi 3 O 8-hollandite and other high-pressure minerals in the shock melt veins of the Suizhou meteorite. Chin. Sci. Bull. 46, 1116–1125 (2001).

Stöffler, D., Hamann, C. & Metzler, K. Shock metamorphism of planetary silicate rocks and sediments: Proposal for an updated classification system. Meteorit. Planetary Sci. 53, 5–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.12912 (2018).

Černok, A., White, L. F., Darling, J., Dunlop, J. & Anand, M. Shock-induced microtextures in lunar apatite and merrillite. Meteorit. Planetary Sci. 54, 1262–1282. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.13278 (2019).

Kusiak, M. A. et al. Nano-and micro-structures in lunar zircon from Apollo 15 and 16 impactites: Implications for age interpretations. Contribut. Mineral. Petrol. 177, 112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-022-01977-8 (2022).

Stojic, A. N. et al. A shock recovery experiment and its implications for Mercury’s surface: The effect of high pressure on porous olivine powder as a regolith analog. Icarus 357, 114162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114162 (2021).

Abate, Y. et al. Nanoscopy of phase separation in Inx Ga1–x N alloys. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 23160–23166. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b06766 (2016).

Henning, T. & Mutschke, H. Low-temperature infrared properties of cosmic dust analogues. Astronomy Astrophys. 327, 743–754 (1997).

Acknowledgements

This work was directly supported by the NASA Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute (SERVI) under cooperative agreement NNA17BF68A (REVEALS) and NNH22ZDA020C (CLEVER).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.G. data acquisition, analysis, writing. M. G., S. S., and S. G., data acquisition and analysis. Y. A., and T.M.O. conceptualization, resources, supervision, data analysis, writing-review, editing. P.C. S., simulation, data analysis, writing, editing. M.J. S and K. L. data analysis, editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grice, A.M., Stancil, P.C., Ghafariasl, M. et al. Nanoscale characterization of space weathering in lunar samples. Sci Rep 15, 301 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83392-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83392-6