Abstract

This study describes the use of the emulsion liquid membrane (ELM) technique to recover thorium (Th(IV)) from an aqueous nitrate solution. The components of the ELM were kerosene as a diluent, sorbitan monooleate (span 80) as a surfactant, bis(2,4,4-trimethylpentyl)phosphinic acid (Cyanex 272) as an extractant, and H2SO4 solution as a stripping reagent. Th(IV) was more successfully extracted and separated under the following favorable conditions: Cyanex272 concentration of 0.11 mol/L; 0.65 mol/L H2SO4 as a stripping phase (internal phase); feed phase (external phase) pH of 1; internal-to-membrane phase volume ratio of 1; emulsion-to-external phase volume ratio of 0.4; contact time of 25 min; and agitation speed of 300 rpm. Under these conditions, the membrane transferred Th(IV) selectively from the real leach liquor without appreciable emulsion breakage or swelling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since nuclear energy is being used more and more in the fields of industry, agriculture, and medicine, it is critical to supply the fuel required for nuclear power plants. It is vital to pay attention to the development of reserves and the identification of alternative fuel sources because the mines that supply the essential fuel are limited, and their extraction is occurring at an increasing rate1. Thorium is a promising fertile material that has attracted a lot of attention as a potential source of nuclear energy due to several attractive characteristics of the thorium fuel cycle, including greater abundance of thorium on earth than uranium, proliferation resistance (thorium reactors could not produce fuel for nuclear weapons), and reduced nuclear waste production (produce fewer radioactive fission products and much less plutonium and other radioactive transuranic elements than uranium)2,3,4,5. In most cases, thorium can be acquired as a by-product of procedures used to extract rare earth elements (REEs) from ore concentrates. Typically, sulfuric acid is used to break ore for four hours at 230 °C in an acid digestion process. The procedure is followed by a selective precipitation method to separate thorium from uranium and rare earth elements (REE) using ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)6. Chung et al. employed hydrometallurgical processes such as water leaching, sulphation, double salt precipitation with Na2SO4, caustic conversion, and acidic leaching with HCl to recover thorium from Korean monazite7. Although most of these impurities are removed from the ore after hydrometallurgical operations, it still has some impurities and therefore cannot be used directly for fuel production. Consequently, it is necessary to perform more purification operations on it.

Currently, the solvent extraction method is one of the most common methods for separating and purifying metal ions. Eskandari Nasab et al. investigated the solvent extraction of Th(IV) utilizing Cyanex272, Cyanex302, and TBP8. It was discovered that Cyanex272 could recover Th(IV) from a 0.5 M nitric acid solution with an extraction efficiency of 83%. The behavior of commercial extractants Cyanex272, Cyanex302, Cyanex301, and PC-88 A in benzene during the extraction of Th(IV) from aqueous HNO3 has been investigated9. In the nitric acid medium, the extraction efficiencies were arranged as follows: Cyanex272 > PC-88 A > Cyanex302 > Cyanex301. In another work, Shaeri et al. investigated the extraction of Th(IV) using a combination of TBP and Cyanex27210.

As the solvent extraction method has some restrictions such as emulsion formation, flooding, extractant loss, phase separation, and low selectivity, the liquid membrane (LM) technique has gained popularity as an alternative for the solvent extraction method. This method’s characteristics include a high separation factor, low energy consumption, economical use of pricey extractants, reduced operating costs, and the ability to combine extraction and stripping processes in a single step11,12,13,14.

LM methods have also been used to extract Th(IV) from aqueous solutions. Yaftian et al. used a bulk liquid membrane (BLM) containing HTTA extractant in carbon tetrachloride for the selective transfer of Th(IV) ions from nitrate solution15. The results indicated that after 8 h, 95.4 (± 1.2)% of the initial concentration of Th(IV) is removed through the BLM into the receiving phase (HCl 0.5 mol/L). Milani et al. looked into the extraction and transfer of Th(IV) utilizing a BLM with 1.5 M H2SO4 as the internal phase and DEHPA extractant (0.2 mol/L)16. This report states that in 16 h, nearly 85% of the Th(IV) was removed. These investigations show BLM is a time-consuming process that is suitable for experimental studies. In another work, a hollow fiber renewal liquid membrane (HFRLM) technique impregnated with Cyanex272 was used to extract of Th(IV) in a continuous process17. The extractant will be readily removed from the pores of the polymer in these types of LM.

Emulsion liquid membrane (ELM) is a promising separation technique among the various LM techniques because it is energy-saving, offers a large interfacial area, produces high mass transfer rates, and is 40% less expensive than solvent extraction18. Li initially developed the ELM technique for hydrocarbon separation in 197119. In this technique, the organic membrane phase and the aqueous internal phase are the two immiscible phases that are first mixed to create the ELM using a high-speed stirrer in the presence of a surfactant. To extract the solute and strip it in the internal phase, the emulsion is dispersed into the external phase. In the end, the solute is recovered by separating the external phase and the emulsion, then breaking the emulsion20.

Over the last few years, the ELM has come to be known as a novel separation technique that is very efficient in removing metal ions21,22,23, hydrocarbons24, and organic species25,26.

Koorepazan Moftakhar et al. studied the practical and selective transport of Th(IV) ions from aqueous solutions across ELM made of paraffin and a surfactant, without an extractant27. They demonstrated that Th(IV) ions were transferred from its mixture solution containing lanthanides La(III), Sm(III), Eu(III), and Er(III) selectively and quantitatively under optimal experimental circumstances. Nevertheless, the amount of Th(IV) recovery was not disclosed by these authors. Reefy et al. created an ELM using TOPO/Span 80/sodium citrate, investigating the variables influencing membrane stability28. The results of the permeability test showed that the membrane could recover 82% of Th(IV) and 98% of U(VI) from an HNO3 solution that contained Ce, Zr, Fe(III), Cd, and Cu.

Despite the ability of ElM to transport metal ions, its limited stability is a major barrier to the widespread industrial deployment of the ELM method. Water transfer into the emulsion (swelling), membrane disintegration, emulsion droplet coalescence, and internal phase leakage (breakage) are all potential causes of low ELM stability29.

The ELM suitable properties for metal ion separation and the Cyanex 272 potential for Th(IV) extraction were used in this work to evaluate an ELM system incorporating Cyanex 272 extractant for Th(IV) separation for the first time. To achieve the highest level of Th(IV) separation with the least amount of ELM breakage and swelling, all relevant parameters, including extractant concentration, stripping agent concentration, agitation speed, contact time, emulsion-to-feed phase volume ratio, and internal-to-membrane phase volume ratio, were examined.

Experiments

Materials

Cyanex 272 extractant was acquired from Sigma Aldrich. Span 80 (about 99.5%) from ACECR, produced locally for the Tehran University branch. A dough polymer known as polyisobutylene (PIB) (≥ 98.0%) (supplied from Sigma Aldrich) with an average molecular mass of 500,000 g/mol was utilized to increase the emulsion stability. Kerosene ( ≤ 100%) as the organic phase solvent was purchased from the Alpha Acer company. Other chemicals, including thorium nitrate (Th(NO3)2.5H2O), KCl, H2SO4 (95–97%), HCl (37.0%), and n-butanol (≥ 99.5%), were prepared from a laboratory-grade by Merck. Every chemical was utilized without any kind of purification.

The pH levels of aqueous phases were measured using a Sartorius pH meter, which was calibrated every day using standard buffer solutions.

Th(IV) and K ion concentrations in aqueous phases were measured using inductivity-coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES, Optima 7300 DV, America).

To prepare the emulsion, a homogenizer (model Ultra-Turrax IKA T18, Germany) was utilized.

Apparatus and procedure

The stock solution of Th(IV) was prepared by adding a certain amount of Th(NO3)2.5H2O in different concentrations of nitric acid solution.

The internal phase, which included the stripping agent (H2SO4 solution), was combined with an organic phase to form the emulsion. KCl as a tracer was added to internal phase for determining the emulsion breakage value. Cyanex 272 as the extractant, Span 80 as the surfactant, and kerosene (including 1.5 Wt.% PIB22) as the diluent were mixed to make the organic phase, also known as the membrane phase. According to our previous work30, Span 80 concentration was considered 3 wt%. To create a stable white, milky emulsion, the internal phase was gradually added to the organic phase and agitated in a homogenizer set at 11,000 rpm for 20 min. The volumetric ratio of the internal phase to the organic phase was thought to be 1:1, except for studies to look into the impact of this parameter.

50 mL of the feed aqueous solution (external phase) was mixed with the precise volume of the created emulsion. After a specific time, the agitated mixture was transferred into a separatory funnel to separate the external phase from the emulsion. (Fig. 1). The concentrations of Th(IV) and K ions in the external phase were measured to determine the extraction efficiency and emulsion breakage, respectively. Then, the volume of the emulsion was measured to calculate the amount of swelling value. After that, the emulsion was broken by adding n-butanol31 to separate the internal phase and measure the concentration of Th(IV). All experiments were repeated three times. The extraction and recovery efficiency of Th(IV) were calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2).

CTh,0, and CTh, ex are the initial and final concentration of Th(IV) in the external phase, respectively. CTh, int is the final concentration of Th(IV) in the internal phase. Vint and Vex are the volume of the internal and external phases, respectively.

The selectivity of the membrane was calculated by the following formula:

where Cint and C0 are the concentration of metal ions in the internal phase and the initial concentration of metal ions in the real leach liquor solution, respectively.

The breakage and swelling of the ELM were measured by the following Eqs.:

Vem, t, and Vem,0 are the emulsion volume at time t and t = 0, respectively. K concentration in the external phase and internal phase are presented by CK,ex and CK,int, respectively.

Results and discussion

Mechanism of Th(IV) transport through the ELM

The following is the reaction process for thorium extraction from nitrate solution using Cyanex 272 as an extractant reagent9,32:

where the dimeric form of the extractant in organic solvents is represented by (HR)2 and the extractant-metal complex in the LM phase by Th(NO3)2R2.2 h.

The following is the thorium stripping process from the organic phase using a stripping solution:

Since the Th(IV) and hydrogen (H+) ions are carried in opposite directions, the mechanism of Th(IV) transport is known as counter-coupled transport because of Eqs. (6), (7).

Figure 2 shows a schematic illustration of the coupled counter-current transport process of Th(IV) and H+ ions via the LM. The following sequential phases make up the transport mechanism for Th(IV) and H+ ions17:

* Reaction of Th(IV) with the extractant (formation of Th(NO3)2R2.2 h complex) at the external-LM interface and simultaneous release of H+ ions in the external phase.

* Diffusion of the Th(NO3)2R2.2 h complex in the organic phase and moving to the LM-internal interface.

* Decomplexation of the Th(NO3)2R2.2 h complex at the internal-LM interface and the release of Th(IV) and extractant in the aqueous internal phase and the organic LM phase, respectively.

* Diffusion of free extractant back towards the LM-external interface.

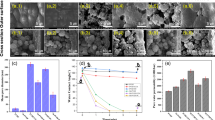

The effect of extractant concentration

Experiments were conducted using different concentrations of Cyanex 272 extractant to determine the maximum extraction and recovery of Th(IV) through ELM with the least quantity of extractant required. Figure 3a displays the results of the findings. As can be observed, the extraction rate of Th(IV) generally increases as the concentration of Cyanex 272 rises. This is because more extractants in the emulsion lead to the creation of more complexes with the metal, which promotes the extraction rate30. Raising the Cyanex 272 concentration higher than 0.11 has no discernible effect on the extraction rate, but the recovery rate decreases from 88.99 to 86.54%. Cyanex 272-Th(IV) complexes saturate the membrane phase, reducing the release rate of metal ions and causing a decrease in Th(IV) recovery when Cyanex 272 concentration rises. Additionally, raising the concentration of Cyanex 272 causes the membrane phase to become more viscous, which inhibits the penetration of soluble complexes through the membrane. This result is further confirmed by Zaheri et al. for the uranium extraction process using an ELM33.

A closer look at the stability of the emulsion in Fig. 3b reveals that adding additional Cyanex 272 causes the emulsion to swell more. It seems that the high concentration of Cyanex 272 acts as a carrier to transfer water into the emulsion, and as a result, the emulsion swells34. The satisfactory stability of the emulsion under these conditions is indicated by the 7.5% swelling percentage in the 0.11 Cyanex 272 concentration. Additionally, Fig. 3b demonstrates that the rate of emulsion breakage in these experiments is quite low (less than 3%). Nonetheless, the 0.8% breakage rate at a very low Cyanex 272 concentration (0.005 mol/L) can be due to the lower viscosity of the organic phase, which makes the emulsion break more easily.

The Effect of extractant concentration on (a) Th(IV) extraction and recovery, (b) emulsion breakage and swelling. (Operating conditions: 3 wt% Span 80, 0.65 mol/L H2SO4 solution, external phase pH: 1, speed of agitation: 300 rpm, contact time: 25 min, emulsion-to-external volume ratio: 0.4, internal-to-membrane volume ratio: 1).

The effect of external phase pH

Since Cyanex 272 extractant is an acidic ligand, the impact of the feed phase pH value on the effectiveness of Th(IV) extraction and recovery has been examined in this section. The findings in Fig. 4 demonstrate that the amount of Th(IV) extraction remains unaffected by varying the pH of the feed phase within the range of 0.1–3. Put otherwise, it is possible to extract Th(IV) almost entirely (over 99%) in this pH range. Additionally, as Fig. 4 shows, raising the pH to 1 causes the proportion of Th recovery from 74.76 to 88.99%. The driving force needed for Th(IV) recovery increases due to the rising pH [see Eq. (6)], which also causes an increase in the proton concentration gradient in both the external and internal phases33. Furthermore, Th(IV) recovery dropped and reached 71.84% with a pH increase of up to 3.

The effect of contact time

All the variables were held constant to examine the impact of phase contact time on Th(IV) extraction and recovery efficiency. It is evident from Fig. 5a that there is not enough time for complete extraction and recovery of Th(IV) in less than 10 min. The amount of Th(IV) extraction and recovery rises with a contact time extension of up to 25 min. Following that, there is less Th(IV) stripped. Rouhani et al. have also reported this effect in the molybdenum ion transfer using an ELM containing Cyanex 272 extractant30. Because extending the duration of the two phases contact gives water molecules ample opportunity to enter the emulsion, causing the emulsion to swell (Fig. 5b). The swelling rate rises sharply from 7.5 to 37.5% as the contact time increases from 25 to 35 min. However, the breakage quantity during 45 min is so little and negligible (around 0.5%).

The Effect of contact time on (a) Th(IV) extraction and recovery, (b) emulsion breakage and swelling. (Operating conditions: 3 wt% Span 80, 0.11 mol/L Cyanex 272, 0.65 mol/L H2SO4 solution, external phase pH: 1, speed of agitation: 300 rpm, emulsion-to-external volume ratio: 0.4, internal-to-membrane volume ratio: 1).

The effect of stripping agent concentration

The movement of Th(IV) ions from the membrane into the internal phase droplets is significantly influenced by the stripping process that occurs at the interface between the internal phase and the organic phase. The effect of stripping agent concentration in the internal phase was examined at various H2SO4 concentrations. As shown in Fig. 6a, the more stripping agent is supplied for Th(IV) transfer as H2SO4 concentration increases up to 0.65 mol/L, increasing extraction efficiency from 3 to 99.85% and recovery efficiency from 3.09 to 88.99%. The transport mechanism in Fig. 2 shows that while the feed phase acidity remains constant, the extraction efficiency (%) rises as the concentration of the internal phase grows because the pH difference between the internal and external phases increases. In other words, more Th(IV) ions are recovered in the internal phase when the H+ concentration in the internal phase is increased. After that, raising the H2SO4 concentration reduces the recovery rate while having minimal effect on the rate of Th(IV) extraction. The instability of the emulsion at high H2SO4 concentrations is the origin of this occurrence. The emulsion volume grows as the concentration of H2SO4 in the internal phase increases, as demonstrated by the swelling measurement (Fig. 6b). The difference in osmotic pressure between the feed phase and the internal phase, which facilitates the transfer of water molecules, appears to be the cause of the emulsion swelling35. The increase in swelling causes the internal phase to be diluted, and as a result, the recovery rate decreases36. Figure 6b also demonstrates the emulsion breakage is negligible.

The Effect of stripping agent concentration on (a) Th(IV) extraction and recovery, (b) emulsion breakage and swelling. (Operating conditions: 3 wt% Span 80, 0.11 mol/L Cyanex 272, external phase pH: 1, speed of agitation: 300 rpm, contact time: 25 min, emulsion-to-external volume ratio: 0.4, internal-to-membrane volume ratio: 1).

The effect of agitation speed

The speed of agitation has a significant impact on the size of emulsion droplets37. The agitation speed should not be set too high to rupture the emulsion, nor should it be set too low to prevent mixing. At speeds ranging from 100 to 700 rpm, multiple tests were conducted to evaluate the impact of this parameter. Figure 7a displays the results that were acquired. Raising the turbulence and speed will increase the mass transfer between the emulsion droplets and the feed phase, boosting extraction. So, the extraction rate increased from 20.33 to 99.94% by increasing the agitation speed from 100 to 200 rpm. The extraction rate remains unchanged when the agitation speed is increased further until 650 rpm. Nevertheless, at speeds greater than 400 rpm, the Th(IV) recovery is significantly decreased and reached 60%. Because in these conditions, the intense shear stress breaks the emulsion droplets, facilitating the diffusion of water molecules to them and therefore swelling increases38,39(Fig. 7b). Destroying the emulsion droplets also leads to a higher breakage rate, consequently reducing the extraction rate at 700 rpm. As a result, 300 rpm was shown to be the appropriate agitation speed for all experiments.

The Effect of agitation speed on (a) Th(IV) extraction and recovery, (b) emulsion breakage and swelling. (Operating conditions: 3 wt% Span 80, 0.65 mol/L H2SO4 solution, 0.11 mol/L Cyanex 272, external phase pH: 1, contact time: 25 min, emulsion-to-external volume ratio: 0.4, internal-to-membrane volume ratio: 1).

The effect of emulsion-to-external phase volume ratio

When evaluating the effectiveness of the ELM method and figuring out the least amount of extractant needed, the emulsion-to-external phase volume ratio is crucial. Consequently, the variable volume for the emulsion was taken into consideration, while the external phase volume was fixed to calculate the proper value of this parameter. Figure 8a shows that an increase in this ratio from 0.2 to 0.4 results in an increase in the amount of Th(IV) extraction and recovery. Because by adding more emulsion, the ability of the internal phase to accumulate Th(IV) ions increments as well as the mass transfer area between the emulsion and the external phase. The Th(IV) recovery will decline as the amount of emulsion rises more. This phenomenon can be explained by an increase in the amount of surfactant, the transfer of more water to the internal phase, and, as a result, emulsion swelling. Li et al. reported a similar effect for Hg separation using an ELM system40. Figure 8b illustrates the quantity of emulsion swelling and breakage as the emulsion-to-feed volume ratio increases. The findings further demonstrate that the emulsion breakage is not significantly impacted by this factor.

The Effect of emulsion to external phase volume ratio on (a) Th(IV) extraction and recovery, (b) emulsion breakage and swelling. (Operating conditions: 3 wt% Span 80, 0.65 mol/L H2SO4 solution, 0.11 mol/L Cyanex 272, external phase pH: 1, agitation speed: 300 rpm, contact time: 25 min, internal-to-membrane volume ratio: 1).

The effect of internal-to-membrane phase volume ratio

Another effective parameter on the stability of the ELM as well as the extraction and recovery of Th(IV) is the volume ratio of the internal phase to the organic phase of the emulsion. Any change in this volume ratio not only changes the emulsion properties but also affects the emulsion capacity to extract the Th(IV) ions. Figure 9a displays the efficiency of Th(IV) extraction and recovery in different ratios. These results were obtained at a contact time of 25 min, 3 wt% span 80, 0.11 mol/L Cyanex 272, 0.65 mol/L H2SO4, and an agitation speed of 300 rpm. This figure illustrates how the Th(IV) transfer rate rises from 12.42 to 89.99% when the volume ratio of the internal phase in the membrane is increased to 1. This is because the complex permeation path has gotten shorter due to the membrane thickness becoming thinner41. Moreover, by increasing the amount of internal phase, the capacity of the internal droplets to strip Th(IV) increases. A further increase in the internal phase volume leads to the dilution of the emulsion, the narrowing of the organic phase layer, and, as a result, the faster transfer of water into the membrane. In other words, a larger amount of internal phase results in a smaller membrane phase volume that can contain all internal reagent molecules18. Therefore, the membrane swells, and the recovery rate decreases38. Figure 9b illustrates the effect of this parameter on the swelling and breakage of the emulsion. The results show the breakage rate is insignificant in these experiments. To minimize emulsion swelling and create a homogenous emulsion, a volume ratio of 1.0 between the internal phase and the organic phase was considered.

The Effect of internal-to-membrane phase volume ratio on (a) Th(IV) extraction and recovery, (b) emulsion breakage and swelling. (Operating conditions: 3 wt% Span 80, 0.65 mol/L H2SO4 solution, 0.11 mol/L Cyanex 272, external phase pH: 1, agitation speed: 300 rpm, contact time: 25 min, emulsion-to external volume ratio: 0.4).

Separation of Th(IV) from a real leach liquor solution

The separation of Th(IV) from the real leach liquor solution was examined by the ELM containing Cyanex 272. In this leach liquor solution, Th(IV) is the dominant element with a concentration of 255 ppm. The solution also contains significant amounts of Fe, Al, Ca, and Si. The specifications of the leach liquor solution and results obtained for extraction, recovery, and selectivity values are reported in Table 1. The results show that the ELM extracts up to 95.55% of Th(IV), while it transfers 70.2% of Th(IV). The highest selectivity value of Th(IV) compared to Al is 57.75. Th(IV) transfer is consistently greater than that of other elements, demonstrating the selectivity of the proposed ELM. The promising results of selectivity by this ELM indicate that this approach will be used in practical applications.

The performance of the proposed ELM system was contrasted with that of various LMs in Table 2. Compared to two ELM systems used for Th(IV) extraction, the ELM used in this investigation has demonstrated better efficiency. Despite the fact that Koorepazan Moftakhar et al. claimed the extraction of Th(IV) to be more than 99% without the use of an extractant, they just reported the quantity of Th(IV) extracted without addressing Th(IV) recovery.

Conclusions

In this work, Th(IV) was extracted with Cyanex 272 from an aqueous nitrate solution and then released into a water-H2SO4 solution by the ELM technique. The impact of every process parameter, including contact time, agitation speed, extractant concentration, stripping phase concentration, external phase pH, internal-to-membrane phase volume ratio, and emulsion-to-external phase volume ratio, was investigated. The data collected demonstrated that the emulsion swelling is considerably influenced by all of the factors under investigation, except for extractant concentration. The emulsion breakage, however, is negligible (less than 2%). Operating parameters such as 0.11 mol/L Cyanex 272, 0.65 mol/L H2SO4 solution, external phase pH of 1, emulsion-to-external phase volume ratio of 0.4, internal-to-membrane phase volume ratio of 1, agitation speed of 300 rpm, and contact time of 25 min resulted in the recovery of more than 89% of Th(IV). Under these conditions, the membrane transferred selectively more than 70% of the Th(IV) in the real leach liquor without experiencing any noticeable swelling (< 8%) or emulsion breakage (< 0.5%). Finally, it can be concluded that the ELM has the potential to be an alternative to the solvent extraction method in the industry. Nonetheless, it is necessary to look into the effectiveness of this method as well as its stability in both large-scale and continuous modes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sokolov, F., Fukuda, K. & Nawada, H. Thorium fuel cycle-Potential benefits and challenges. IAEA TECDOC 1450 (2005).

Yuan, L. Y. et al. Introduction of bifunctional groups into mesoporous silica for enhancing uptake of thorium (IV) from aqueous solution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 6, 4786–4796 (2014).

Li, R. et al. The recovery of uranium from irradiated thorium by extraction with di-1-methyl heptyl methylphosphonate (DMHMP)/n-dodecane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 188, 219–227 (2017).

Li, L. et al. The novel extractants, bis-triamides: Synthesis and selective extraction of thorium (IV) from nitric acid media. Sep. Purif. Technol. 188, 485–492 (2017).

Hinwood, A. L. et al. Maternal exposure to alkali, alkali earth, transition and other metals: concentrations and predictors of exposure. Environ. Pollut. 204, 256–263 (2015).

Kumari, A., Panda, R., Jha, M. K., Kumar, J. R. & Lee, J. Y. Process development to recover rare earth metals from monazite mineral: A review. Miner. Eng. 79, 102–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2015.05.003 (2015).

Chung, K. W., Yoon, H. S., Kim, C. J., Lee, J. Y. & Jyothi, R. K. Solvent extraction, separation and recovery of thorium from Korean monazite leach liquors for nuclear industry applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 83, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2019.11.014 (2020).

Nasab, M. E., Sam, A. & Milani, S. A. Determination of optimum process conditions for the separation of thorium and rare earth elements by solvent extraction. Hydrometallurgy 106, 141–147 (2011).

Mansingh, P., Chakravortty, V. & Dash, K. Solvent extraction of thorium (IV) by Cyanex 272/Cyanex 302/Cyanex 301/PC-88A and their binary mixtures with TBP/DOSO from Aq. HNO3 and H2SO4 media. Radiochim. Acta. 73, 139–144 (1996).

Shaeri, M., Torab-Mostaedi, M. & Rahbar Kelishami, A. Solvent extraction of thorium from nitrate medium by TBP, Cyanex272 and their mixture. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 303, 2093–2099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-014-3718-5 (2015).

Kislik, V. Liquid Membranes: Principles and Applications in Chemical Separations and Wastewater Treatment. (1st ed), 17-18 (Elsevier, 2009).

Zahakifar, F., Charkhi, A., Torab-Mostaedi, M. & Davarkhah, R. Performance evaluation of hollow fiber renewal liquid membrane for extraction of uranium (VI) from acidic sulfate solution. Radiochim. Acta. 106, 181–189 (2018).

Zahakifar, F., Charkhi, A., Torab-Mostaedi, M. & Davarkhah, R. Kinetic study of uranium transport via a bulk liquid membrane containing Alamine 336 as a carrier. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 316, 247–255 (2018).

Zahakifar, F., Charkhi, A., Torab-Mostaedi, M., Davarkhah, R. & Yadollahi, A. Effect of surfactants on the performance of hollow fiber renewal liquid membrane (HFRLM): a case study of uranium transfer. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 318, 973–983 (2018).

Yaftian, M. R., Zamani, A. & Rostamnia, S. Thorium (IV) ion-selective transport through a bulk liquid membrane containing 2-thenoyltrifluoroacetone as extractant-carrier. Sep. Purif. Technol. 49, 71–75 (2006).

Milani, S., Zahakifar, F. & Faryadi, M. Membrane assisted transport of thorium (IV) across bulk liquid membrane containing DEHPA as ion carrier: kinetic, mechanism and thermodynamic studies. Radiochim. Acta. 110, 841–852 (2022).

Allahyari, S. A., Minuchehr, A., Ahmadi, S. J. & Charkhi, A. Thorium pertraction through hollow fiber renewal liquid membrane (HFRLM) using Cyanex 272 as carrier. Prog. Nucl. Energy. 100, 209–220 (2017).

Kumar, A., Thakur, A. & Panesar, P. S. A review on emulsion liquid membrane (ELM) for the treatment of various industrial effluent streams. Reviews Environ. Sci. BioTechnol.. 18, 153–182 (2019).

Li, N. N. Separation of hydrocarbons by liquid membrane permeation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Process. Des. Dev. 10, 215–221 (1971).

Yaghoobi, M., Zaheri, P., Mousavi, S. H., Ardehali, B. A. & Yousefi, T. Evaluation of mean diameter and drop size distribution of an emulsion liquid membrane system in a horizontal mixer-settler. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 167, 231–241 (2021).

Suliman, S. S., Othman, N., Noah, N. F. M. & Kahar, I. N. S. Extraction and enrichment of zinc from chloride media using emulsion liquid membrane: Emulsion stability and demulsification via heating-ultrasonic method. J. Mol. Liq. 374, 121261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2023.121261 (2023).

Ardehali, B. A., Zaheri, P. & Yousefi, T. The effect of operational conditions on the stability and efficiency of an emulsion liquid membrane system for removal of uranium. Prog. Nucl. Energy. 130, 103532 (2020).

Gasser, M. S., Kadry, H. F., Helal, A. S. & Abdel Rahman, R. O. Optimization and modeling of Uranium recovery from acidic aqueous solutions using liquid membrane with Lix-622 as Phenolic-oxime carrier. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 180, 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2022.02.002 (2022).

Al-Obaidi, Q., Alabdulmuhsin, M., Tolstik, A., Trautman, J. G. & Al-Dahhan, M. Removal of hydrocarbons of 4-Nitrophenol by emulsion liquid membrane (ELM) using magnetic Fe2O3 nanoparticles and ionic liquid. J. Water Process. Eng. 39, 101729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101729 (2021).

Sulaiman, R. N. R. et al. Phenol recovery using continuous emulsion liquid membrane (CELM) process. Chem. Eng. Commun. 208, 483–499 (2021).

Peng, W., Jiao, H., Shi, H. & Xu, C. The application of emulsion liquid membrane process and heat-induced demulsification for removal of pyridine from aqueous solutions. Desalination 286, 372–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2011.11.051 (2012).

Koorepazan, M. F., Habibi, L. & Yaftian, M. R. Selective and Efficient Ligandless Water-in-Oil Emulsion Liquid Membrane Transport of Thorium (IV) Ions. (2016).

El-Reefy, S. A., Selim, Y. T. & Aly, H. F. Equilibrium and kinetic studies on the separation of uranium and thorium from nitric acid medium by liquid emulsion membrane based on trioctylphosphine oxide extractant. Anal. Sci. 13, 333–337 (1997).

Admawi, H. K. & Mohammed, A. A. A comprehensive review of emulsion liquid membrane for toxic contaminants removal: An overview on emulsion stability and extraction efficiency. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 109936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.109936 (2023).

Rouhani, S. H. R., Davarkhah, R., Zaheri, P. & Mousavian, S. M. A. Separation of molybdenum from spent HDS catalysts using emulsion liquid membrane system. Chem. Eng. Processing-Process Intensif. 153, 107958 (2020).

Larson, K., Raghuraman, B. & Wiencek, J. Electrical and chemical demulsification techniques for microemulsion liquid membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 91, 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/0376-7388(94)80085-5 (1994).

El-Dessouky, S., El-Hefny, N. & Daoud, J. A. Studies on the equilibrium and mechanism of Th (IV) extraction by CYANEX 272 in kerosene from nitrate medium. Radiochim. Acta. 92, 25–30 (2004).

Zaheri, P. & Davarkhah, R. Rapid removal of uranium from aqueous solution by emulsion liquid membrane containing thenoyltrifluoroacetone. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 5, 4064–4068 (2017).

Chiha, M., Samar, M. H. & Hamdaoui, O. Extraction of chromium (VI) from sulphuric acid aqueous solutions by a liquid surfactant membrane (LSM). Desalination 194, 69–80 (2006).

Othman, N., Hie, C. K., Tung, C., Mat, H. & Goto, M. Emulsion liquid membrane extraction of silver from photographic waste using tetramethylthiuram disulfide (TMTDS) as a mobile carrier. J. Appl. Membrane Sci. Technol. 3, 1-14 (2006).

Kulkarni, P. S. & Mahajani, V. V. Application of liquid emulsion membrane (LEM) process for enrichment of molybdenum from aqueous solutions. J. Membr. Sci. 201, 123–135 (2002).

Noble, R. D., & Koval, C. A. Review of facilitated transport membranes. Materials Science of Membranes for Gas and Vapor Separation, 411-435 (Wiley Online Library, 2006).

Kumbasar, R. A. Cobalt–nickel separation from acidic thiocyanate leach solutions by emulsion liquid membranes (ELMs) using TOPO as carrier. Sep. Purif. Technol. 68, 208–215 (2009).

Kumbasar, R. A. Selective extraction of cobalt from strong acidic solutions containing cobalt and nickel through emulsion liquid membrane using TIOA as carrier. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 18, 2076–2082 (2012).

Li, Q., Liu, Q. & Wei, X. Separation study of mercury through an emulsion liquid membrane. Talanta 43, 1837–1842 (1996).

Tang, B., Yu, G., Fang, J. & Shi, T. Recovery of high-purity silver directly from dilute effluents by an emulsion liquid membrane-crystallization process. J. Hazard. Mater. 177, 377–383 (2010).

Ammari Allahyari, S., Charkhi, A., Ahmadi, S. J. & Minuchehr, A. Modeling and experimental validation of the steady-state counteractive facilitated transport of Th (IV) and hydrogen ions through hollow-fiber renewal liquid membrane. Chem. Pap. 75, 325–336 (2021).

Alamdar Milani, S., Zahakifar, F. & Charkhi, A. Continuous bulk liquid membrane technique for thorium transport: modeling and experimental validation. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 16, 455–464 (2019).

Dinkar, A. et al. Carrier facilitated transport of thorium from HCl medium using Cyanex 923 in n-dodecane containing supported liquid membrane. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 298, 707–715 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P. Z. and D.E. wrote the main manuscript. P. Z. and D.E. prepared all figures.F. Z. wrote Sect. 3.1 and 3.9.F. Z. prepared all tables.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ehyaie, D., Zaheri, P., Samadfam, M. et al. Evaluation of cyanex272 in the emulsion liquid membrane system for separation of thorium. Sci Rep 14, 31897 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83397-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83397-1