Abstract

This is the first study to evaluate the adequacy and reliability of the ChatGPT and Gemini chatbots on viral hepatitis. A total of 176 questions were composed from three different categories. The first group includes “questions and answers (Q&As) for the public” determined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The second group includes strong recommendations of international guidelines. The third group includes frequently asked questions on social media platforms. The answers of the chatbots were evaluated by two different infectious diseases specialists on a scoring scale from 1 to 4. Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated to assess inter-rater reliability. The reproducibility and correlation of answers generated by ChatGPT and Gemini were analyzed. ChatGPT and Gemini’s mean scores (3.55 ± 0.83 vs. 3.57 ± 0.89, p = 0.260) and completely correct response rates (71.0% vs. 78.4%, p = 0.111) were similar. In addition, in subgroup analyses with the CDC questions Sect. (90.1% vs. 91.9%, p = 0.752), the guideline questions Sect. (49.4% vs. 61.4%, p = 0.140), and the social media platform questions Sect. (82.5% vs. 90%, p = 0.335), the completely correct answers rates were similar. There was a moderate positive correlation between ChatGPT and Gemini chatbots’ answers (r = 0.633, p < 0.001). Reproducibility rates of answers to questions were 91.3% in ChatGPT and 92% in Gemini (p = 0.710). According to Cohen’s kappa test, there was a substantial inter-rater agreement for both ChatGPT (κ = 0.720) and Gemini (κ = 0.704). ChatGPT and Gemini successfully answered CDC questions and social media platform questions, but the correct answer rates were insufficient for guideline questions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatitis, known as inflammation of the liver, can be caused by both infectious agents (e.g. viral, bacterial, and fungal microorganisms) and non-infectious factors (e.g. alcohol use, metabolic disorders, and autoimmune diseases)1. Among these causes, the most common causes of hepatitis are viral infections, especially viral hepatitis. There are five main types of hepatitis virus (A, B, C, D, E) that cause infection in humans. Although all of these hepatitis viruses cause liver diseases, they differ significantly in key aspects such as routes of transmission, geographic distribution, severity of disease, and prevention methods2. Viral hepatitis is an important public health problem that infects millions of people every year, causing serious morbidity and mortality3. For this reason, it is of great importance to provide accurate information about the epidemiology and measures to prevent the transmission of the disease in sources frequently used by society, such as the internet and social media.

Artificial intelligence models have started to be used in medicine in recent years, as in many branches of science. These models have been used in the field of infectious diseases, especially in improving laboratory diagnostic performance and for information about diagnosis and clinical prognosis4. Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer (ChatGPT, San Francisco, California, USA), created by OpenAI, is a text-based artificial intelligence model that acts as a natural multi-language chatbot5. Similarly, Gemini (Google, Mountain View, California, USA) is a text-based artificial intelligence model developed by Google6. Unlike social media platforms, ChatGPT and Gemini are freely accessible chatbots that collate information from many reliable sources. As these applications became accessible, their popularity increased rapidly and became a frequently used resource in social life. Although these chatbots are thought to be promising in providing consistent answers, artificial intelligence applications can sometimes give wrong directions and cause an information epidemic called “infodemic”, which can also threaten public health7. For this reason, it is very important to evaluate the reliability and adequacy of the information provided by these artificial intelligence chatbots.

Many studies are currently being conducted on the reliability and adequacy of ChatGPT in different clinical branches of medicine8,9,10,11. Whereas successful results are reported8,9,10, there are also unsuccessful results11. A very limited number of studies have been reported regarding the Gemini chatbot12,13. To the best of our knowledge, there is no study evaluating and comparing the knowledge levels of these chatbots about viral hepatitis. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the adequacy and reliability of the ChatGPT and Gemini chatbots’ knowledge levels about viral hepatitis.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted between March 1, 2024 and March 30, 2024. The first group includes “questions and answers (Q&As) for the public” determined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)14. The second group includes strong evidence-based recommendations of international guidelines on viral hepatitis. All questions prepared from the guidelines were at the level of ‘high level of evidence’ and/or ‘strong recommendation’. In addition, questions covering basic information were prepared from the general information accepted in international guidelines. The guideline questions were prepared from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) guideline for hepatitis A15, and from the European Association for the Study of Liver Disease (EASL) guideline for hepatitis B, hepatitis D, and hepatitis E16,17,18. For Hepatitis C, EASL and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines were considered as sources19,20. Of all the guidelines, only questions with a strong recommendation level were included. In addition, treatment-related guideline questions were also evaluated through subgroup analysis. The third group includes frequently asked questions on social media platforms (Google, YouTube, Facebook, X [formerly named Twitter]). The terms “Hepatitis A,” “Hepatitis B,” “Hepatitis C,” “Hepatitis D,” and “Hepatitis E” were searched online. In addition, the questions asked about viral hepatitis on the websites of healthcare associations were evaluated and “social media platform questions” were determined. The questions were rigorously assessed for suitability for the study by two infectious diseases and clinical microbiology specialists. Questions with similar meanings, repetitive questions, questions with unclear answers, questions that were subjective or may vary between patients, questions not related to viral hepatitis, and questions containing grammatical errors were excluded from the study. A total of 176 questions were included. Of those, 34.7% (n = 61) were CDC questions, 42.6% (n = 75) were guideline questions, and 22.7% (n = 40) were social media platform questions. Scores of ChatGPT and Gemini according to questions are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and Supplementary Table 2, respectively.

In this study, ChatGPT 3.5 and Google Gemini 1.5 Flash were used to answer the questions. The default settings were used for both versions of language models. The answers were evaluated separately by two experienced infectious diseases and clinical microbiology experts who were also the authors of the study (the first expert had 10 years of professional experience and the second expert had 9 years of professional experience). Answers that were not in agreement by two specialists were evaluated by a third infectious diseases and clinical microbiology specialist who had 10 years of professional experience. The scores for the answers that were not in agreement by three specialists were discussed together. Then, the final scoring was determined by complete agreement.

A standard scoring system was used for reviewers to evaluate the quality and reliability of answers on ChatGPT and Gemini chatbots. On this scale between 1 and 4 points, the answers were evaluated as follows:

-

1.

point: Completely wrong or irrelevant answer.

-

2.

point: Mixed answer with true and misleading information (information that may lead to misdirection).

-

3.

point: Generally correct but insufficient answer (incomplete information available, more detailed explanation required).

-

4.

point: Completely correct and sufficient answer (no other information to add).

In order to evaluate the reproducibility of the answers given to the questions, each question was asked to two different computers at different times. If the answers produced by both computers to the prepared questions were the same, it was defined as a “consistent response”. If the content of the answers between the two computers was not similar, it was defined as an “inconsistent response”. In this case, only the first response from the chatbots was scored. Reproducibility rates were assessed by question category and compared between chatbots. Ethics committee approval was not required in this study because no patient data was used.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (sd), and categorical variables were presented as numbers (n) and percentages (%). The T-test was used to compare normally distributed continuous parameters, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare non-normally distributed continuous parameters. The Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated to assess inter-rater reliability14. Spearman’s correlation analysis was performed to investigate the association between the answers generated by ChatGPT and those generated by Gemini. Results with a p-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 176 questions related with hepatitis A (n = 33, 18.8%), hepatitis B (n = 52, 29.5%), hepatitis C (n = 37, 21.0%), hepatitis D (n = 30, 17.0%), and hepatitis E (n = 24, 13.7%) were included in the study. According to Cohen’s kappa test, there was a substantial inter-rater agreement for both ChatGPT (κ = 0.720, 95% CI 0.71–0.73) and Gemini (κ = 0.704, 95% CI 0.69–0.71).

ChatGPT provided completely correct answers to 125 (71.0%) questions, correct but inadequate answers to 30 questions (17.1%), misleading answers to 12 (6.8%) questions, and completely wrong answers to 9 (5.1%) questions. Of the answers, 90.1% (n = 55/61) in the CDC questions section, 49.4% (n = 37/75) in the guideline questions section, and 82.5% (n = 33/40) in the social media platform questions section were evaluated as completely correct (Table 1). The completely correct answer rate provided by ChatGPT to the questions in the treatment-related sections of the guideline recommendations was 42.8% (n = 15/35). Regarding viral hepatitis types, 75.7% (n = 25/33) of the answers related hepatitis A, 65.3% (n = 34/52) of the answers related hepatitis B, 70.3% (n = 34/52) of the answers related hepatitis C, 60.0% (n = 26/37) of the answers related hepatitis D, and 91.6% (n = 22/24) of the answers related hepatitis E were completely correct. Completely correct answer rates of guideline questions were lower than those of social media platform questions (49.4% vs. 85.0%, p < 0.001, OR:5.81, 95% CI 2.18–15.48) and CDC questions (49.4% vs. 90.1%, p < 0.001, OR:9.41, 95% CI 3.61–24.50).

Gemini provided completely correct answers to 138 (78.4%) questions, correct but inadequate answers to 13 questions (7.4%), misleading answers to 13 (7.4%) questions, and completely wrong answers to 12 (6.8%) questions. Of the answers, 91.9% (n = 56/61) in the CDC questions section, 61.4% (n = 46/75) in the guideline questions section, and 90.0% (n = 36/40) in the social media platform questions section were evaluated as completely correct (Table 2). The completely correct answer rate provided by Gemini to the questions in the treatment-related sections of the guideline recommendations was 42.8% (n = 15/35). Regarding viral hepatitis types, 84.8% (n = 28/33) of the answers related hepatitis A, 75% (n = 39/52) of the answers related hepatitis B, 70.3% (n = 34/52) of the answers related hepatitis C, 76.6% (n = 23/30) of the answers related hepatitis D, and 91.6% (n = 22/24) of the answers related hepatitis E were completely correct. Completely correct answer rates to guideline questions were lower than those for social media platform questions (61.4% vs. 90.0%, p = 0.002, OR: 3.04, 95% CI 1.82–17.61) and CDC questions (61.4% vs. 91.9%, p < 0.001, OR: 7.06, 95% CI 2.53–19.70).

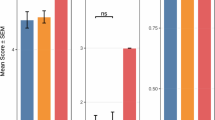

The mean score of answers generated by ChatGPT was 3.55 ± 0.83, while the mean score of answers generated by Gemini was 3.57 ± 0.89 (p = 0.260). The comparison of the scores for the answers generated by ChatGPT and Gemini according to question categories is shown in Fig. 1. There was no significant difference between ChatGPT and Google Gemini in completely correct answers rates (71.0% vs. 78.4%, p = 0.111, OR: 0.67). In addition, in subgroup analyses with the CDC questions section (p = 0.752), the guideline questions section (p = 0.140), and the social media platform questions section (p = 0.335), the completely correct answers rates were similar. There was a moderate positive correlation between ChatGPT and Gemini chatbots’ answers (r = 0.633, p < 0.001). Distribution of the scores for answers generated by ChatGPT and Gemini is shown in Fig. 2. Reproducibility rates of answers to questions were 91.3% in ChatGPT and 92% in Gemini (p = 0.710). The comparison of the reproducibility rates of answers according to question groups is shown in Fig. 3.

Distribution of the scores for answers generated by ChatGPT and Gemini. The vertical axis on the left shows the score given to responses generated by ChatGPT, and the vertical axis on the right shows the scores given to responses generated by Gemini. Questions with the same score on both platforms are shown in blue, and questions with different scores are shown in red. The horizontal line shows the questions with the same score.

Discussion

In recent years, with the introduction of artificial intelligence platforms, their potential benefits and drawbacks in the field of medicine are frequently discussed. Artificial intelligence may decrease the workload on the health systems by raising awareness among people about diseases. However, there are some concerns about the reliability of artificial intelligence15,16. Therefore, we conducted a study aiming to evaluate the level of knowledge and reliability of ChatGPT and Gemini chatbots about viral hepatitis, which is the most common infectious cause of liver cirrhosis and cancer. In our study, ChatGPT and Gemini successfully answered CDC questions (90.1% vs. 91.9%) and social media platform questions (82.5% vs. 90.0%), but the correct answer rates were insufficient for guideline questions (49.4% vs. 61.4%). In addition, the reproducibility rates of these chatbots were high (ChatGPT: 91.3% vs. Gemini: 92%). However, both chatbots had the same low rates of correct answers (ChatGPT: 42.8% vs. Gemini: 42.8%) for questions related to treatment recommendations in the guidelines.

Many studies have reported that ChatGPT successfully answers questions about medicine on the internet and social media8,9,17. Ozgor et al. found that ChatGPT provided completely accurate answers to 91.4% of questions about endometriosis8. In the study of Tuncer et al., ChatGPT answered 92.5% of social media questions in the field of infectious diseases completely correct9. In another study, ChatGPT correctly answered 96.2% of questions about urinary tract infections17. In our study, although slightly lower than other studies, the completely correct answer rates of social media platform questions and CDC questions were 82.5% and 90.1%, respectively. In addition, while ChatGPT provided misleading answers to 5% of social media platform questions, it did not provide any misleading answers for the CDC questions. These results justify that ChatGPT can be a reliable source for informing the public about viral hepatitis.

Studies on ChatGPT’s compliance with medical guideline recommendations report lower rates of successful answer18,19. In the study of Dyckhoff-Shen et al., ChatGPT correctly answered 70% of the questions prepared from the European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) Brain Abscess Guideline18. The correct answers rates in the questions prepared from the guideline recommendations of the studies of Tuncer et al.9 and Çınar et al.19 were 69.2% and 61.3%, respectively. Contrary to the above studies, in the study of Çakır et al., the accuracy rate of ChatGPT for guideline questions was 89.7%17. In our study, ChatGPT answered half of the guideline-based inquiries completely correctly. In addition, a quarter of questions were answered correctly, even though they contained insufficient information. When the question types were examined, we found a low correct answer rate in the section related to treatment. This resulted in ChatGPT to provide higher rates of successful answers to questions generated from guidelines on hepatitis A and hepatitis E, which do not yet contain strong recommendations regarding treatment.

Google Gemini, formerly known as Google Bard, has been reported to be less successful than ChatGPT in a limited number of studies assessing the level of knowledge in the field of medicine12,13,20. One study evaluating questions about immuno-oncology reported that Google Bard provided a lower rate of successful answers than ChatGPT-3.5 (43.8% vs. 58.5%, p = 0.03)20. In the study by Liu et al., 20 questions were asked about breast implant disease (BII) and breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL). It was stated that Google scored lower than ChatGPT in both BII-related (2.66, vs. 4.28, p < 0.01) and BIA-ALCL-related (2.72 vs. 4.18, p < 0.01) questions13. In our study, the total scores of ChatGPT (3.55) and Gemini (3.57) were similar. Likewise, completely correct answer rates between the two chatbots were similar. Unlike previous studies, we showed that Gemini was as successful as ChatGPT. This may be explained with multiple situations which may have significant impact. First of all, there is no published research on viral hepatitis. Therefore, a direct comparison cannot be made. In addition, these artificial intelligence applications are constantly updating themselves. Therefore, the answers produced by the artificial intelligence models in the studies may not be consistent with each other. These may lead to different results.

This study is the first to evaluate the adequacy and reliability of ChatGPT and Gemini in addressing public and guideline-based questions on viral hepatitis. However, our study has some limitations. First, the small sample size for the evaluation of social media platform questions limits the generalizability of the results. Second, the questions selected for analyses are not representative of all questions researched by the public and encountered in clinical practice. Third, since the adequacy of ChatGPT and Gemini answers are evaluated by infectious diseases and clinical microbiology specialists, comments may contain subjectivity due to human nature. Although the answers were evaluated by at least two specialists, differences in interpretations may affect the scoring process. Fourth, we did not assess the understandability of the information for the general public by a scoring system such as the PEMAT. The evaluation of the questions was performed by specialists. Therefore, no robust conclusion can be drawn about the understandability of ChatGPT and Gemini answers for people with different socio-cultural levels.

Conclusion

In conclusion, ChatGPT and Gemini chatbots appear to have the potential as an important resource that the community can use to gather accurate information about viral hepatitis. If the low rates of misleading answers generated by ChatGPT and Gemini are minimized, these chatbots may be a candidate to become an substantial part of preventive health measures in the near future. However, it should be emphasized that these chatbots do not yet provide sufficient and reliable information for healthcare professionals.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sayed, I. M., El-Shamy, A. & Abdelwahab, S. F. Emerging pathogens causing Acute Hepatitis. Microorganisms 11 (12), 2952. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11122952 (2023).

Hepatitis & World Health Organization. March. https://www.who.int/health-topics/hepatitis#tab=tab_1. Accessed 11 (2024).

Bhadoria, A. S. et al. Viral Hepatitis as a Public Health Concern: A Narrative Review About the Current Scenario and the Way Forward [published correction appears in Cureus. Cureus. 14(2), e21907. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.21907 (2022).

Tran, N. K. et al. Evolving Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Infectious diseases Testing. Clin. Chem. 68(1), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvab239 (2021).

Zhou, Z. Evaluation of ChatGPT’s capabilities in Medical Report Generation. Cureus 15 (4), e37589. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.37589 (2023).

Gemini & an AI experiment by Google. https://gemini.google.com/app/85a900c3648714da. Accessed 20 March 2024.

De Angelis, L. et al. ChatGPT and the rise of large language models: the new AI-driven infodemic threat in public health. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1166120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1166120 (2023).

Ozgor, B. Y. & Simavi, M. A. Accuracy and reproducibility of ChatGPT’s free version answers about endometriosis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Published Online Dec. 18 https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.15309 (2023).

Tunçer, G. & Güçlü, K. G. How reliable is ChatGPT as a novel consultant in infectious diseases and clinical microbiology? Infect. Dis. Clin. Microbiol. 6 (1), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.36519/idcm.2024.286 (2024).

Caglar, U. et al. Evaluating the performance of ChatGPT in answering questions related to pediatric urology. J. Pediatr. Urol. 20 (1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2023.08.003 (2024).

Maillard, A. et al. Can Chatbot artificial intelligence replace infectious disease physicians in the management of bloodstream infections? A prospective cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. Published Online Oct. 12 https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad632 (2023).

Carlà, M. M. et al. Exploring AI-chatbots’ capability to suggest surgical planning in ophthalmology: ChatGPT versus Google Gemini analysis of retinal detachment cases. Br. J. Ophthalmol. Published Online March. 6 https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo-2023-325143 (2024).

Liu, H. Y. et al. Consulting the Digital Doctor: Google Versus ChatGPT as sources of information on breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic large cell lymphoma and breast Implant Illness. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 48 (4), 590–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-023-03713-4 (2024).

Viral hepatitis, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/index.html. Accessed 23 November 2024.

Nelson, N. P., Weng, M. K., Hofmeister, M. G., Moore, K. L., Doshani, M., Kamili, S., et al. Prevention of Hepatitis A Virus Infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2020 [published correction appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021 Feb 26;70(8):294. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7008a5]. MMWR Recomm Rep. 69(5), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6905a1 (2020).

European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Association for the study of the liver. EASL 2017 clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J. Hepatol. 67 (2), 370–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021 (2017).

European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Association for the study of the liver. EASL Clinical Practice guidelines on Hepatitis delta virus. J. Hepatol. 79 (2), 433–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.05.001 (2023).

European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Association for the study of the liver. EASL Clinical Practice guidelines on Hepatitis E virus infection. J. Hepatol. 68 (6), 1256–1271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.005 (2018).

European Association for the Study of the Liver. Clinical Practice Guidelines Panel: Chair:; EASL Governing Board representative:; Panel members:. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: Final update of the series [published correction appears in J Hepatol. 2023 Feb;78(2):452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2022.10.006]. J Hepatol. 73(5), 1170–1218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.08.018 (2020).

Bhattacharya, D. et al. AASLD-IDSA Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Clin Infect Dis. Published online May 25, 2023. Update https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad319 (2023).

McHugh, M. L. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. (Zagreb). 22 (3), 276–282 (2012).

Gilson, A. et al. How does ChatGPT perform on the United States Medical Licensing examination? The implications of Large Language Models for Medical Education and Knowledge Assessment. JMIR Med. Educ. 9, e45312. https://doi.org/10.2196/45312 (2023).

Zhou, Z., Wang, X., Li, X. & Liao, L. Is ChatGPT an evidence-based Doctor? Eur. Urol. 84 (3), 355–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2023.03.037 (2023).

Cakir, H. et al. Evaluating ChatGPT ability to answer urinary tract infection-related questions. Infect. Dis. now.. Published Online March. 8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idnow.2024.104884 (2024).

Dyckhoff-Shen, S., Koedel, U., Brouwer, M. C., Bodilsen, J. & Klein, M. ChatGPT fails challenging the recent ESCMID brain abscess guideline. J. Neurol. 271 (4), 2086–2101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-023-12168-1 (2024).

Cinar, C. Analyzing the performance of ChatGPT about osteoporosis. Cureus 15 (9), e45890. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.45890 (2023).

Iannantuono, G. M. et al. Comparison of large Language models in answering Immuno-Oncology questions: a cross-sectional study. Oncologist Published Online Febr. 3. https://doi.org/10.1093/oncolo/oyae009 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sena Alkan, M.D., who contributed as the third specialist for the answers that were not in agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.O and Y.E.O. designed the study. M.S.O. and Y.E.O. collected the data. Y.E.O. and M.S.O. performed the management and the analysis of the data. All authors interpreted the results of the analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by M.S.O and Y.E.O. All authors have read the manuscript and approved the final version to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sahin Ozdemir, M., Ozdemir, Y.E. Comparison of the performances between ChatGPT and Gemini in answering questions on viral hepatitis. Sci Rep 15, 1712 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83575-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83575-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comparison of the accuracy and reliability of ChatGPT-4o and Gemini in answering HIV-related questions

BMC Infectious Diseases (2025)

-

Comparing ChatGPT-3.5, Gemini 2.0, and DeepSeek V3 for pediatric pneumonia learning in medical students

Scientific Reports (2025)