Abstract

The Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) has emerged as a cost-effective biomarker for systemic inflammation and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, yet its prognostic value in critically ill patients with heart failure (HF) remains unclear. Leveraging the MIMIC-IV database, this study investigates the association between PLR and 1-year all-cause mortality in 7,217 ICU patients with HF. Patients were stratified into tertiles (0–126.45, 126.45–252.40, and 252.40–1000), and mortality risk was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and Cox proportional hazards models. Elevated PLR was independently associated with higher mortality, with the highest tertile showing a 36% increased risk compared to the lowest (HR 1.36, 95% CI: 1.23–1.50, P < 0.001). Each tertile increment corresponded to a 17% rise in risk. Subgroup analyses revealed stronger associations in hypertensive patients and identified renal dysfunction and red cell distribution width as key modifiers. Integrating PLR with SOFA and APS III scores significantly enhanced predictive accuracy. By reflecting systemic inflammation and immune dysregulation, PLR offers a robust tool for long-term risk stratification and personalized management of ICU patients with HF. These findings highlight the potential of PLR to refine prognostic models, guide clinical decision-making, and improve critical care outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a rapidly escalating global epidemic, affecting more than 64 million individuals and contributing to over 1 million hospitalizations annually in the United States and Europe1. As a progressive syndrome that often marks the terminal stage of various cardiovascular diseases, HF places significant clinical and economic burdens on healthcare systems. This burden is particularly acute for critically ill patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs), who often face acute decompensation or life-threatening complications such as cardiogenic shock, arrhythmias, or multi-organ failure2. In this vulnerable population, the 1-year mortality rate exceeds 23%, underscoring the urgent need for reliable, cost-effective biomarkers to guide clinical decision-making and improve patient outcomes3.

Inflammation plays a crucial role in the progression and adverse outcomes associated with HF, especially in ICU patients, where inflammatory responses are often heightened. The Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR), a novel biomarker derived from routine blood tests, has gained attention for its potential as a prognostic tool. PLR reflects two critical components of the inflammatory response: the prothrombotic activity of platelets and the immune-regulatory function of lymphocytes4. Elevated PLR levels have been associated with poor outcomes in a range of cardiovascular diseases, including acute myocardial infarction and coronary artery disease5,6,7. In HF patients, higher PLR values may indicate systemic vascular inflammation, which exacerbates myocardial injury, fibrosis, and pathological cardiac remodeling, ultimately leading to increased mortality8.

While PLR’s short-term prognostic value—particularly in predicting in-hospital9and 30-day mortality10—has been documented, its ability to forecast long-term outcomes, such as 1-year all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with HF, remains underexplored. For example, one study reported that a higher PLR (> 139.23) was associated with poorer 6-month survival in 443 patients with acute HF11, while conflicting results were found by Pourafkari et al.12, who reported that PLR involving 354 patients was not an independent predictor of acute HF after a 5-year follow-up. These discrepancies, likely arising from relatively small sample sizes, heterogeneous populations, and differing methodologies13, highlight the need for large-scale, well-designed studies to definitively assess PLR’s long-term prognostic significance in ICU patients with HF.

To address this gap and explore its potential as a reliable biomarker for risk stratification, our study investigates the association between PLR and 1-year all-cause mortality in ICU patients with HF, utilizing the comprehensive MIMIC-IV database.

Materials and methods

Study population

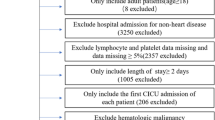

This retrospective study utilized the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV, version 2.2) database, which includes over 190,000 ICU admissions from 2008 to 2019. The study focused on adult patients diagnosed with heart failure (HF), identified via ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes. Inclusion criteria mandated that all patients were admitted to the ICU for the first time with an HF diagnosis and were ≥ 18 years old. We excluded individuals with incomplete platelet or lymphocyte data and those with ICU stays shorter than 24 h. In total, 7217 patients met these criteria and were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). The study adhered to ethical guidelines, and informed consent was waived due to the use of de-identified data for secondary analysis.

Data collection and outcome measures

Data collection occurred within 24 h of ICU admission and included demographic factors (age, gender, weight, and height), comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]), vital signs (respiratory rate, heart rate, oxygen saturation, systolic and diastolic blood pressure), laboratory results (hemoglobin, red cell distribution width [RDW], platelet count, white blood cell count, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, electrolyte, bicarbonate, coagulation indicators), and medication details (inotropes, vasopressors, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, β-blockers). Mechanical ventilation and continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) data were also recorded.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 1-year follow-up. Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) was calculated as the ratio of absolute platelet count to absolute lymphocyte count, obtained through routine blood tests using an automated analyzer, with extreme values (> 1000) recorded as 1000.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared across PLR tertiles using appropriate statistical tests, including ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis H, and chi-square tests. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), while categorical variables were shown as percentages. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Log-Rank tests were used to evaluate differences in mortality outcomes across PLR categories. PLR was analyzed as a categorical (tertiles), ordinal (per tertile increase), and continuous (per standard deviation increase) variable within four Cox proportional hazards models, with hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) computed to assess mortality risk. The models were adjusted as follows: Model 0: Unadjusted, PLR alone. Model 1: Adjustment for demographics (e.g., age, gender) and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, COPD). Model 2: Further adjustment for Model 1 variables plus anemia (hemoglobin, RDW), kidney function (creatinine, BUN, chloride, anion gap), and treatments (β-blockers, vasopressors, and inotropes) and interventions (CRRT, mechanical ventilation). Model 3: Included all Model 2 adjustments, adding the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) and Acute Physiology Score (APS) III. The lowest PLR tertile served as the reference across all analyses.

For clinical applicability, the maximally selected rank statistics method, supported by the ‘survminer’ package, was used to determine the optimal PLR cutoff point associated with survival outcomes. A restricted cubic spline analysis was conducted to evaluate the linear or nonlinear dose-response relationship between PLR and mortality risk, using the median PLR value as a reference.

Subgroup analyses and interaction tests examined the prognostic significance of PLR across demographic and clinical subgroups. Sensitivity analysis performed with modified Poisson regression confirmed the robustness of the results. The predictive accuracy of PLR, individually and alongside SOFA and APS III scores, was assessed via the concordance index (C-index) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses. All analyses were performed in R software (version 4.3.1), with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

Population baseline characteristics

Table 1 outlines the baseline characteristics of the 7,217 participants, stratified into PLR tertiles (T1: 0.00–126.45, T2: 126.45–252.40, T3: 252.40–1000). Participants in higher PLR tertiles were older, more likely to be female, had a greater prevalence of COPD, and exhibited more severe clinical measurements, including deteriorating renal function and abnormal vital signs.

Over the 365-day follow-up period, 2,694 participants (37.3%) died. A stepwise increase in one-year all-cause mortality was observed across PLR tertiles, with mortality rates of 28.5%, 36.4%, and 47.1% for T1, T2, and T3, respectively (P < 0.001).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed significant differences in cumulative survival rates across PLR tertiles during the 1-year follow-up period (Fig. 2A). Patients with higher PLR levels exhibited markedly lower survival rates compared to those with lower PLR levels, with statistically significant differences observed among the tertiles (P < 0.001). Furthermore, the optimal PLR cutoff value for predicting survival outcomes was determined to be 281.3 using the maximally selected rank statistics method (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Kaplan-Meier survival curves stratified by this cutoff value (high vs. low PLR groups) demonstrated a significant difference in 1-year all-cause mortality between the two groups (Supplementary Fig. 1B, P < 0.001).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves and restricted cubic spline analysis. (A) Cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality according to PLR tertiles, estimated using Kaplan-Meier survival curves. (B) Restricted cubic spline analysis illustrating the linear relationship between PLR and all-cause mortality, adjusted for all variables. The red solid line represented the hazard ratio, and the black dashed lines represented 95% confidence interval.

Adjusted hazard ratios

In Model 1, the risk of 1-year all-cause mortality increased significantly with rising PLR tertiles (P for trend < 0.0001) (Table 2), and this trend remained consistent in Model 2. In Model 3, after multivariate adjustments for age, gender, comorbidities, vital signs, laboratory results, treatments, and critical illness scores, the HRs for all-cause mortality in T2 and T3 compared to T1 were 1.11 (95% CI, 1.00–1.23) and 1.36 (95% CI, 1.23–1.50), respectively (P for trend < 0.001).

When PLR was treated as an ordinal variable, each increase in tertile was associated with a 17% higher risk of mortality (HR 1.17, 95% CI, 1.12–1.23). As a continuous variable, each standard deviation increase in PLR was associated with a 12% increase in mortality risk (HR 1.12, 95% CI, 1.08–1.16).

Restricted cubic spline analysis

The restricted cubic spline analysis facilitates the examination of linear or non-linear relationships between variables, which is particularly relevant in clinical research. Based on Model 3, which included comprehensive multivariate adjustments for potential confounders, the analysis revealed a linear association between increasing PLR levels and elevated mortality risk, with no statistically significant evidence of nonlinearity (P for nonlinearity = 0.055). Specifically, as PLR levels increase, the risk of all-cause mortality rises accordingly, emphasizing the robustness of PLR as a marker in this population (Fig. 2B).

Subgroup analyses and interaction tests

Subgroup analyses included all categorical and continuous variables that might influence the association between the PLR and all-cause mortality outcomes, such as age distribution, gender, comorbidities, and laboratory tests. The analysis demonstrated that the positive association between PLR and all-cause mortality was consistent across various categorical groups, except for patients with hypertension, where a significant interaction was detected (P for interaction = 0.003, Fig. 3A). Namely, the PLR values of hypertensive HF patients had stronger association with 1-year mortality. Among the continuous variables examined, four measurements—respiratory rate, RDW, serum creatinine, and BUN—were identified as negatively impacting the prognostic effect of PLR on mortality risk (all P for interaction < 0.05, Fig. 3B).

Subgroup analyses of the prognostic effect of PLR on mortality. (A) Hypertension significantly modulated the association between PLR and mortality (P for interaction = 0.003). (B) Continuous variables, including respiratory rate, red cell distribution width, serum creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen, negatively influenced the prognostic effect of PLR on mortality (all P for interaction < 0.05).

C-index and ROC analyses

We assessed the predictive value of PLR for 1-year mortality in conjunction with the widely used SOFA and APS III scores, using the C-index as the evaluation metric. The C-index values for PLR, SOFA, and APS III were 0.58 (95% CI, 0.57–0.59), 0.61 (95% CI, 0.60–0.62), and 0.68 (95% CI, 0.67–0.69), respectively (Table 3). The integration of PLR with the SOFA score significantly improved predictive performance, raising the C-index to 0.64 (95% CI, 0.63–0.65; P < 0.001). Similarly, combining PLR with the APS III score yielded a C-index of 0.69 (95% CI, 0.68–0.70; P < 0.001), demonstrating significant enhancements in predictive accuracy compared to using the SOFA or APS III scores alone.

The ROC analyses further confirmed these findings. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for PLR, SOFA, and APS III in predicting 1-year all-cause mortality in HF patients was presented in Supplementary Fig. 2. The combined models (PLR + SOFA and PLR + APS III) demonstrated significantly higher predictive performance than SOFA or APS III scores alone (P < 0.001 for both comparisons; see Supplementary Table 1).

Sensitivity analysis

In sensitivity analysis using modified Poisson regression, the positive correlation between PLR tertiles and all-cause mortality risk was confirmed, with a risk ratio (RR) of 1.15 (95% CI, 1.11–1.19, P < 0.001), reinforcing the robustness of the association (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between the PLR and 1-year all-cause mortality in patients with HF, utilizing a large and critically ill population from the MIMIC-IV database. Through the examination of clinical data from 7,217 HF patients, we demonstrated a significant linear association between elevated PLR levels and increased mortality risk. Importantly, this relationship persisted even after adjusting for confounding factors, such as age, gender, comorbidities, and widely used risk scores like SOFA and APS III, indicating PLR’s independent prognostic value.

In decompensated HF, activated platelets interact with leukocytes and endothelial cells, initiating an immune response that triggers the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and promotes oxidative stress7. This inflammatory cascade impairs vascular homeostasis and exacerbates fluid retention, contributing to adverse clinical outcomes8. Under these stressful conditions, increased cortisol secretion due to the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, along with leukocyte recruitment from the bloodstream to tissues, can lead to a decrease in absolute lymphocyte count, concomitantly resulting in an elevated PLR14.

PLR has recently emerged as a cost-effective biomarker of immune activation and inflammation, with multiple studies suggesting its utility in predicting mortality in cardiovascular diseases7. For instance, in a cohort of 288 acute myocardial infarction patients, elevated PLR levels (> 178) were associated with poor hospital outcomes, including higher rates of heart rupture, acute HF, and all-cause mortality15. Another study involving 1,161 physicians identified PLR as an independent predictor of coronary artery disease16. Additionally, several studies have linked PLR with both in-hospital and out-of-hospital mortality in acute decompensated HF10,11,17, however, these findings have not been universally corroborated18,19. Of note, one study with a small sample of only 56 HF patients found no independent predictive value of PLR for all-cause mortality, after a mean follow-up of 12.8 ± 7.6 months20. The discordant results across studies were largely attributed to limited sample sizes, varying methodologies, and inconsistent follow-up durations.

Building upon this existing evidence, our study assessed the prognostic significance of PLR for 1-year all-cause mortality in a large cohort of ICU patients with HF. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, multivariate Cox regression models, and modified Poisson regression for sensitivity analysis consistently showed that PLR serves as a significant stratification factor for mortality risk (Fig. 2; Table 2, Supplementary Table 2). These findings suggest that PLR could serve as a valuable biomarker for refining long-term mortality risk stratification in ICU patients with HF, with meaningful implications for clinical practice.

The dose-response relationship between PLR and mortality risk was further confirmed by restricted cubic spline analysis, which demonstrated a linear association between PLR levels and mortality. Meanwhile, patients with PLR levels experienced a 12% increase in the risk of mortality per standard deviation increase in PLR. Moreover, the optimal PLR cutoff value for predicting 1-year survival outcomes was identified as 281.3 in this population. These findings offer a clearer understanding of the relationship between PLR and survival, providing clinicians with a useful biomarker for refining risk stratification strategies in ICU settings.

Subgroup and interaction analyses revealed that the prognostic effect of the PLR on mortality was particularly pronounced in hypertensive patients, indicating that this subgroup may require closer monitoring of PLR levels. Additionally, factors such as renal function (serum creatinine and BUN), respiratory rate, and RDW were identified as modulators of the prognostic impact of PLR. It is well established that renal function is closely related to HF outcomes21,22,23, and the interplay between cardiac and renal functions means that dysfunction in one system can exacerbate issues in the other18. Respiratory rate serves as an indicator of hypoxia24, while RDW reflects chronic inflammation, malnutrition, anemia, and oxidative stress25,26. When these factors deteriorate, the prognostic utility of PLR diminishes, likely due to the dominant influence of these other pathological processes27,28. Conversely, in patients with relatively stable physiological parameters, PLR retains its association with 1-year mortality. This highlights the importance of monitoring PLR levels, even in clinically stable or improving patients, as elevated PLR levels remain associated with poor survival outcomes in the subsequent year.

Ultimately, we examined the predictive power of the PLR for 1-year mortality. The SOFA score is designed to evaluate the function of six major organs and the severity of multiple organ failure, thereby aiding in the prognosis of ICU patients29. Similarly, the APS III quantifies a patient’s physiological state and assesses the risk of death based on a series of parameters within the first 24 h of admission30. Although both scoring systems demonstrate robust predictive power for mortality risk, they do not incorporate parameters that directly reflect inflammatory responses. In this context, our study revealed that PLR, as a representative inflammatory marker, complements the limitations of these scoring systems. Integrating PLR with SOFA and APS III significantly improved predictive accuracy, as evidenced by higher C-index and AUC values. This underscores the added value of incorporating PLR into existing prediction models, providing a more comprehensive assessment of mortality risk. The combination of PLR with these scoring systems addresses the critical role of inflammation in HF pathophysiology and provides a more comprehensive approach to mortality risk stratification, potentially improving clinical decision-making and patient outcomes.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, as a retrospective cohort analysis, it is subject to selection bias and residual confounding. Despite adjustments for multiple variables, critical clinical data—such as prior cardiovascular history, natriuretic peptide levels, left ventricular function, and post-discharge treatments—were unavailable in this database. Furthermore, single-time measurements of platelet and lymphocyte counts limited the evaluation of temporal changes in inflammatory status. The lack of time-dependent covariate analysis further restricted the understanding of the dynamic relationship between PLR and mortality risk. Future studies should adopt prospective designs incorporating real-time monitoring and longitudinal analyses to better capture these dynamics and enhance clinical applicability. Finally, although this study focuses on PLR, other composite inflammatory biomarkers, such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and systemic immune-inflammation index, have also demonstrated prognostic value in HF31,32. Future research should comprehensively compare these markers to determine their relative predictive utility in HF populations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that elevated PLR levels are independently associated with an increased risk of 1-year all-cause mortality in ICU patients with HF. As a simple, cost-effective biomarker, PLR holds great potential for improving long-term risk stratification and clinical decision-making in critically ill patients. Moreover, integrating PLR into established prognostic models, such as the SOFA and APS III scores, significantly enhances predictive accuracy. Future prospective studies should explore the dynamic changes in PLR over time, aiming to refine personalized treatment strategies and improve outcomes for HF patients in critical care.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets obtained from the MIMIC IV database (https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/2.2/) were analyzed in this study. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Roger, V. L. Epidemiology of Heart Failure: A Contemporary Perspective. Circ. Res. 128, 1421–1434 (2021).

McDonagh, T. A. et al. 2021 Esc Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Eur. Heart J. 42, 3599–3726 (2021).

Crespo-Leiro, M. G. et al. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry (Esc-Hf-Lt): 1-Year Follow-Up Outcomes and Differences Across Regions. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 18, 613–625 (2016).

Dahlen, B. et al. The Impact of Platelet Indices On Clinical Outcome in Heart Failure: Results From the Myovasc Study. Esc Heart Fail. 8, 2991–3001 (2021).

Siedlecki, A. et al. Mortality Risk Factors in Patients with Advanced Heart Failure and Diabetes Mellitus. Kardiol Pol. 77, 604–609 (2019).

Li, L. et al. Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Relates to Poor Prognosis in Elderly Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 33, 619–624 (2021).

Kurtul, A. & Ornek, E. Platelet to Lymphocyte Ratio in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review. Angiology 70, 802–818 (2019).

Njoroge, J. N. & Teerlink, J. R. Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Approaches to Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 128, 1468–1486 (2021).

Delcea, C. et al. Comparative Role of Hematological Indices for the Assessment of in-Hospital Outcome of Heart Failure Patients. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 55, 227–236 (2021).

Turcato, G. et al. Evaluation of Neutrophil-Lymphocyte and Platelet-Lymphocyte Ratios as Predictors of 30-Day Mortality in Patients Hospitalized for an Episode of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. J. Med. Biochem. 38, 452–460 (2019).

Ye, G. L. et al. The Prognostic Role of Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Acute Heart Failure: A Cohort Study. Sci. Rep. 9, 10639 (2019).

Pourafkari, L. et al. Platelet-Lymphocyte Ratio in Prediction of Outcome of Acute Heart Failure. Biomark. Med. 12, 63–70 (2018).

Delcea, C., Buzea, C. A., Vîjan, A. E., Bădilă, E. & Dan, G. A. The Platelet to Lymphocyte Ratio in Heart Failure: A Comprehensive Review. Rom J. Intern. Med. 61, 84–97 (2023).

Huang, W. M. et al. Hemographic Indices are Associated with Mortality in Acute Heart Failure. Sci. Rep. 7, 17828 (2017).

Wang, H., Li, L. & Ma, Y. Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio a Potential Prognosticator in Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Clin. Cardiol. 46, 632–638 (2023).

Tangjitgamol, S., Udayachalerm, W., Wanishsawad, C., Kaewwanna, W. & Ativanichayapong, N. Association of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Coronary Artery Disease Among the Physicians. J. Inflamm. Res. 17, 59–66 (2024).

Tamaki, S. et al. Combination of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratios as a Novel Predictor of Cardiac Death in Patients with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure with Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction: A Multicenter Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, e26326 (2023).

Heidarpour, M. et al. The Association Between Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio with Mortality Among Patients Suffering From Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. Bmc Cardiovasc. Disord. 21, 454 (2021).

Sadeghi, M. T. et al. Role of Circulatory Leukocyte Based Indices in Short-Term Mortality of Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Med. Pharm. Rep. 93, 351–356 (2020).

Durmus, E. et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio are Predictors of Heart Failure. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 105, 606–613 (2015).

Feng, S. et al. Association of Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction with Worsening Renal Function in Patients with Acute Heart Failure: Insights From the Relax-Ahf-2 Study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 23, 58–67 (2021).

Girerd, N. Worsening Renal Function Precedes and Follows Worsening Heart Failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 24, 1915–1917 (2022).

Zhang, G. et al. Ai Hybrid Survival Assessment for Advanced Heart Failure Patients with Renal Dysfunction. Nat. Commun. 15, 6756 (2024).

McCartan, T. A. et al. The Effectiveness of Continuous Respiratory Rate Monitoring in Predicting Hypoxic and Pyrexic Events: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Physiol. Meas. 42, 065005 (2021).

Parizadeh, S. M. et al. The Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Red Cell Distribution Width in Cardiovascular Disease; Current Status and Prospective. Biofactors 45, 507–516 (2019).

Liu, C. et al. Higher Preoperative Red Blood Cell Distribution Width Increases the Risk of Myocardial Injury After Noncardiac Surgery in Advanced-Age Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin. Interv Aging. 18, 169–179 (2023).

Lal, S., Campbell, K., Li, A. & Editorial Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Heart Failure: Pathophysiology, Pathogenesis and Therapeutics. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1260483 (2023).

Shah, A. K., Bhullar, S. K., Elimban, V. & Dhalla, N. S. Oxidative Stress as a Mechanism for Functional Alterations in Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure. Antioxidants. 10, (2021).

Li, A. et al. Prognostic Evaluation of Quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score in Icu Patients with Sepsis Across Different Income Settings. Crit. Care. 28, 30 (2024).

Ma, Q. B. et al. Performance of Simplified Acute Physiology Score 3 in Predicting Hospital Mortality in Emergency Intensive Care Unit. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 130, 1544–1551 (2017).

Liu, T. et al. Correlation Analysis Between the Static and the Changed Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and in-Hospital Mortality in Critical Patients with Acute Heart Failure. Postgrad. Med. 135, 50–57 (2023).

Zhu, D. et al. The Associations of Two Novel Inflammation Biomarkers, SIRI and SII, with Mortality Risk in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. J. Inflamm. Res. 17, 1255–1264 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to the patients who contributed to this research and to the MIMIC team for their efforts in organizing and maintaining this invaluable database. We also deeply appreciate the reviewers for their insightful and kind comments.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers: 32071110 and Yin Yue-Hui).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.H. performed the study and wrote the manuscript; S. C. provided methodological support; H. D. and Y. Y. provided guidance and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All data used in this study were sourced from the MIMIC-IV database, which is approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. As the study did not involve any direct patient intervention and all health information was anonymized, the need for individual patient consent was waived.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, X., Cheng, S., Du, H. et al. Association of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio with 1-year all-cause mortality in ICU patients with heart failure. Sci Rep 14, 32016 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83583-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83583-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association between platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and 28-day all-cause mortality in patients with asymptomatic coronary artery disease: a cohort study

European Journal of Medical Research (2025)