Abstract

To ensure the safe extraction of deep mineral resources, it is imperative to address the mechanical properties and damage mechanism of coal and rock media under the real-time coupling effect of high temperature and impact. In this study, the impact tests (impact velocities of 6.0–10.0 m/s) on coal-series limestone under real-time high-temperature conditions (25 °C-800 °C) were conducted by the real-time high-temperature split Hopkinson pressure bar (HT-SHPB) testing system, and the microscopic changes in mineral composition under the coupling effect of real-time high-temperature and high strain rate action were investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD), electron scanning microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). The results showed that the dynamic stress-strain curve of coal-series limestone under the real-time coupling effect of high temperature and impact during the compaction stage was not significant; As the impact velocity increases and the temperature increases, the plastic characteristics of the dynamic stress-strain curve become more notable, and the brittle failure of the sample is gradually changed into brittle-ductile failure. Additionally, the dynamic peak stress and dynamic elastic modulus exhibit distinct quadratic variations with the increased temperature, and the dynamic peak stress approximately increases linearly with the impact velocity. The main substances in coal-series limestone are calcite, dolomite, and muscovite. The microscopic morphology of calcite at room temperature is characterized by a thin stepped or layered structure. When the temperature rises to 800 °C, thermal decomposition rarely occurs in calcite, while its physical and mechanical properties undergo alternations. After real-time impact, the degree of crystal fragmentation of calcite increases and a large number of microcracks are generated. The dolomite exhibits a prismatic microscopic morphology at room temperature, characterized by distinct and flat edges, and typically occurs in clusters. When the temperature rises to 600 °C, an increased amount of dolomite initiates thermal decomposition, and the crystal edges become passive, even leading to the granulation phenomenon. Consequently, the impact mechanical properties of limestone are ultimately weakened due to the thermal decomposition of mineral components and changes in physical and mechanical properties caused by high temperature.

Similar content being viewed by others

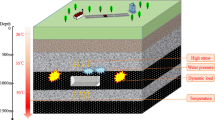

With the gradual depletion of shallow coal resources, the mining of deep coal resources will inevitably become a future development trend1,2,3. However, a multitude of challenges can be encountered during the deep coal mining, including heightened frequency and intensity of rock burst occurrences, increased risk of coal and gas outburst, enhanced appearance of mining pressure in the mining area, more serious water inrush accidents and the significant increase in ground temperature. Among them, the coupling of a high-temperature environment and strong disturbance leads to frequent occurrences of profound engineering disasters, thereby exacerbating the challenges associated with disaster prediction and control. In response to the complexity of deep mining, fluidized mining technology has emerged as one of the predominant methodologies4. To ensure the secure mining of deep coal resources, it is urgent to study the dynamic characteristics and failure mechanisms of deep rock masses under high-temperature dynamic loads.

Studies on the mechanical properties of rock masses at high temperatures have been extensively conducted, including compressive strength5,6, tensile strength7,8, elastic modulus9,10,11, Poisson’s ratio12,13, cohesive force14,15, and friction angle16,17. Researchers have conducted experiments on the dynamic properties of rocks by using the split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) system and its improved test system18,19. The results showed that the mechanical properties of the rock under the dynamic loading are significantly different from those under the static loading20,21,22,23. Yan ‘s research18 results indicate that the dynamic deformation modulus of rocks is not rate-dependent, while the dynamic strength and total strength perform evident rate-dependence. Wang21 studied the influence of dynamic disturbance on the mechanical properties of rock damage. The experimental results show that the dynamic strength and deformation ability of the sample gradually decrease with the increase of impact times. Chen’s research23 shows that under an impact load, a higher strain rate can lead to larger increasing times of the dynamic compressive strength when compared with static loading. The investigation of rock mechanical properties under the coupling effect of high temperature and high strain rate has emerged as a prominent research area, driven by advancements in technologies such as geothermal resource extraction24,25, underground disposal and treatment of nuclear waste26,27, and deep mineral resource extraction28,29. The mechanical properties of the rock exhibit significant disparities under the coupling effect of high temperature and high strain rate from those under a single high temperature or high strain rate conditions30,31,32. At present, most studies on the mechanical properties of rocks under high temperatures and high strain rates are conducted by using rock samples after high-temperature treatment for mechanical impact tests. However, the surrounding rock matrix of coal gasification mining engineering is in a real-time high-temperature environment, and its mechanical properties after impact disturbance are inevitably completely different from those after high-temperature action. Additionally, the changes in mechanical properties of rocks under high temperature and impact are highly intricate, primarily attributed to the exceedingly complex microstructure and mineral composition of rocks. For example, granite is mainly composed of quartz, mica, and feldspar, sandstone is mainly composed of clay, quartz or feldspar, and limestone is mainly composed of calcite, dolomite, muscovite, and clay. The mineral composition and microstructure of similar rocks vary significantly across different regions, and even within the same region, rock samples extracted from the same rock mass exhibit discernible disparities in their microstructure and mineral composition. Under the action of high temperature, the original cracks and pores inside the rock undergo changes and rearrangement in the microstructure. When the temperature reaches the critical value, mineral components begin to undergo physical and chemical changes such as melting and thermal decomposition. As a result, the mechanical properties of the rock change from brittleness to ductility plasticity, which has a significant impact on the macroscopic dynamic properties of the rock. At present, there are few reports on the dynamic mechanical properties of coal-measures limestone under real-time temperature conditions.

In this study, the real-time high-temperature split Hopkinson pressure bar (HT-SHPB) test system was used to conduct impact tests on coal-series limestone under real-time high-temperature conditions (temperatures of 25 °C, 100 °C, 200 °C, 300 °C, 400 °C, 500 °C, 600 °C, 700 °C, 800 °C; impact velocities of 6.0 ~ 10.0 m/s), the microscopic changes in mineral composition under the coupling effect of real-time high-temperature and high strain rate action were investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD), electron scanning microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), and its microscopic damage and deterioration mechanism were obtained. This study provides a reference for deep mining of coal resources and other engineering projects.

Sample preparation and HT-SHPB testing system

Materials and samples

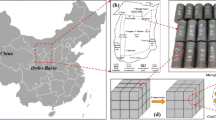

The coal-series limestone used in this study was taken from the Jiagou coal mine in Xuzhou City, China. Based on the recommendations of the International Society for Rock Mechanics and Technical specifications for testing method of rock dynamic properties (T/CSRME001-2019), the sample size was determined as Ф 50 mm × L50 mm. Figure 1 shows a certain part of the processed rock samples. After polishing, the unevenness of the two ends of the sample was controlled to be less than 0.05 mm, and the error of the end face perpendicular to the axis of the sample was less than 0.25°. The mineral composition and content of coal-series limestone were analyzed by XRD. As shown in Fig. 2, the coal-series limestone is mainly composed of 79% calcite (CaCO3), 19% dolomite (CaMg (CO3) 2), and 2% muscovite (KAl2 (Si3AlO10) (OH) 2).

HT-SHPB testing system and procedures

This experiment adopted a real-time high-temperature split Hopkinson pressure bar (HT-SHPB) testing system, and its model was LWKJ-HPKS-Y100. Specifically, it included a pressure loading module (composed of a high-pressure nitrogen cylinder, a high-pressure chamber, a launch chamber, and a pressure controller), a rod main module (composed of bullets, incident rods, transmission rods, absorption rods, and buffers), an information acquisition and analysis module (composed of strain gauges, ultra-dynamic strain gauges, transient waveform storage devices, and speedometers), and a high-temperature processing module (composed of a high-temperature environment box and a temperature controller), as shown in Fig. 3. The high-temperature environment box is placed between the incident bar and the transmission bar to heat the sample and maintain its real-time high-temperature state. But during the experiment. To eliminate the impact of high temperature on the entire system, the impact bar, incident bar, transmission bar, and absorption bar were all fabricated using high-strength and high-temperature resistant materials with a diameter of 50 mm. These materials exhibited a material density of 7580 kg/m3, an elastic modulus of 210 GPa, a longitudinal wave velocity of 5190 m/s, and an ultimate strength exceeding 500 MPa.。However, simply using a high-temperature environment furnace to heat the sample not only takes a long heating time, but also the continuous high-temperature thermal radiation can cause thermal damage to the incident and transmission bars, seriously reducing the service life of the bar. In order to improve experimental efficiency and reduce bar loss, the MF-1200 C box type high-temperature furnace was used to preheat the sample at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. After reaching the target temperature, the sample was kept at a constant temperature for 6 h to ensure uniform heating inside and outside the coal bearing mudstone sample. Then, the sample was placed in a high-temperature environment furnace between the incident bar and the transmission bar using a tongs to maintain a constant temperature of 20 min, ensuring that the real-time temperature displayed by the temperature controller is within ± 1 °C of the preset temperature difference. The sensitivity coefficient and resistance of the strain gauge (ZEMIC) are 110 and 120 Ω, respectively. The Wheatstone half-bridge circuit is selected as the wiring mode. All the strain gauges are recorded by the dynamic strain collector (SDY2017 B) at a sampling frequency of 1 MHz. The material of the shaper used in this paper is a round rubber sheet with a diameter of 10 mm and a thickness of 2 mm.

The three-wave method was used to process data33.as presented in Eq. (1)

where LS and AS represent the original length and the cross-sectional area of the specimen; E0, A0 and C0 denote the elastic modulus, the cross-section area and the wave velocity of the bar; εI(t), εR(t) and εT(t) are the strain histories of the incident bar, reflected bar, and transmitted bar at a time t.

To verify the assumptions of one-dimensional stress wave propagation and uniformity, the incident wave and reflected wave are superimposed, as shown in Fig. 4, which basically coincides with the transmitted wave. In addition, the equilibrium index R(t) is introduced for quantitative analysis, with R(t) < 2% as the judgment criterion. The calculation formula is34:

The R(t) between the two vertical curves is less than 2%, and the corresponding time is the total equilibrium time. The total equilibrium time is greater than 4 times the time when the stress wave passes through the specimen, indicating that the experiment can simultaneously meet the conditions of constant impact velocity and stress equilibrium, verifying the feasibility of the device.

The procedure for the HT-SHPB test is as follows:

-

(1)

Leveling treatment was carried out on the entire rod system, and the bullet, incident rod, transmission rod, and absorption rod were all located on the same axis through a limit ruler. A 2 mm thick rubber sheet was pasted at the front end of the incident rod as a pulse-shaping plate, and the incident wave, initially rectangular in shape, was modified to a half-sine waveform to ensure the uniform distribution of stress during impact-induced damage.

-

(2)

The rock sample was placed into an external heating box and heated at a heating rate of 10 °C/min to the target temperature. After reaching the preset temperature, the constant temperature was maintained for 4 h to ensure uniform heating of the sample35.

-

(3)

The heating switch of the high-temperature environment box was activated, the internal temperature was increased to the target temperature through the temperature controller, and tongs were used to to clamp the sample that had been heated in the external heating box into the high-temperature environment box, and the transfer time was minimized to reduce temperature loss. and the stable insulation was maintained for 10 min. If the real-time temperature displayed by the temperature controller fluctuates more than 5 °C compared to the preset temperature, insulation treatment should be continued until the difference between the real-time temperature and the preset temperature is less than 5 °C.

-

(4)

The preset impact pressure was adjusted, the launch controller was used to launch bullets for impact testing, and the real-time data were collected using a tachometer and dynamic strain collection system.

-

(5)

After the completion of each impact test, the high-temperature furnace was quickly opened, and a collection tool was employed to quickly remove the sample fragments and placed in an external heating box. The gradient cooling method was employed to reduce the temperature inside the external heating box to room temperature, and then all rock sample fragments were removed.

In this study, the HT-SHPB testing system was applied to conduct real-time high-temperature impact tests on coal-series limestone. The temperatures were set at 25 °C, 100 °C, 200 °C, 300 °C, 400 °C, 500 °C, 600 °C, 700 °C, and 800 °C, respectively. The impact velocity and strain rate factors were controlled by setting the impact pressure to 0.5 MPa, 0.6 MPa, 0.7 MPa, 0.8 MPa, and 0.9 MPa.

In addition, XRD, SEM and EDS were used to systematically analyze the changes of mineral composition, micromorphology, elemental composition and proportion of limestone samples after high temperature treatment.

Macroscopic mechanical characteristics of coal-bearing limestone

Dynamic stress-strain curve

Figure 5 shows the dynamic stress-strain curve of coal-series limestone under real-time high-temperature impact. It can be seen that the dynamic stress-strain curve exhibits a notable elastic stage, plastic stage, and failure stage, as well as a negligible compaction stage at each temperature. This finding is significantly different from the dynamic compression characteristics of limestone after high-temperature treatment. Ping Qi et al.reported that when the temperature exceeded 300 °C, the dynamic stress-strain curve of limestone under high temperature exhibited a significant compaction stage, which was mainly due to the closure of micro-cracks inside the limestone sample caused by external loads. These cracks were generated by the high-temperature cooling thermal impact effect34,35. However, under real-time high temperatures, the rock does not undergo thermal impact damage, and the internal mineral crystals undergo thermal expansion. Consequently, there is no notable compaction feature during impact compression.

Dynamic peak stress

Figures 6 and 7 show the variation patterns of dynamic peak stress with temperature and impact velocity. As shown in Fig. 6, as the temperature increases, the dynamic peak stress first increases and then decreases, exhibiting a parabolic nonlinear change pattern. This finding is consistent with the previous studies25. The increase in real-time temperature leads to an expansion of the grain volume within the rock, resulting in a gradual closure of initial pores and a reduction in initial damage. At this time, when the rock sample is subjected to impact, the peak stress of the rock is enhanced. As the real-time temperature further increases, the non-uniform expansion of grains inside the rock intensifies, leading to enhanced compression of the surrounding medium and generation of additional damage. squeezing the surrounding medium and generating new damage. Meanwhile, dolomite and other substances undergo thermal decomposition, leading to increased initial damage to the sample. At this time, when impact is applied to the rock sample, its peak stress is decreased. When the impact velocity is 6.0–7.0 m/s, the maximum dynamic peak stress of the rock sample (138.0 MPa) occurs at about 300 °C; When the impact velocity is 7.0 ~ 8.0 m/s, the maximum dynamic peak stress (172.1 MPa) occurs at about 200 °C; When the impact velocity is 8.0 ~ 10.0 m/s, the maximum dynamic peak stress (231.4 MPa) occurs at about 100 °C. As the impact velocity increases, the enhancing effect of temperature on the peak stress of the sample gradually weakens, and there is a gradual decrease in the temperature at which the maximum dynamic peak stress occurs.

As illustrated in Fig. 7, at different temperatures, the dynamic peak stress approximately increases linearly as the impact velocity increases. When the temperature increases from 25 °C to 400 °C, the peak stress occurs near the fitting curve of 25 °C. When the temperature increases from 400 °C to 700 °C, the peak stress significantly decreases compared to that of 25 °C; When the temperature increases to 800 °C, the peak stress significantly decreases. This indicates that the damage caused by the temperature inside the rock undergoes a qualitative change when the temperature reaches 800 °C.

Dynamic elastic modulus

Figure 8 shows the variation curve of the dynamic elastic modulus of coal-series limestone with temperature. As presented in Fig. 8, as the temperature increases, the dynamic elastic modulus first increases and then decreases, showing a non-linear change pattern. This variation curve is approximately a parabola. When the impact velocity is 6.0–8.0 m/s, the maximum dynamic elastic modulus occurs at 200 °C. When the temperature increases from 25 °C to 800 °C, the dynamic elastic modulus decreases from 73.49 GPa to 33.40 GPa, with a decrease of 54.6% and a decrease rate of about 0.05 GP/°C. When the impact velocity is 8.0–10.0 m/s, the dynamic elastic modulus decreases from 142.88 GPa to 52.06 GPa, with a decrease of 63.6% and a decrease rate of approximately 0.12 GP/°C. The increase of elastic modulus with strain rate is not significant and will not be discussed in this paper.

Macro failure patterns

Figure 9 shows the failure characteristics of coal-series limestone after impact at real-time temperature. It can be found that when the real-time temperature is fixed, the degree of macroscopic fragmentation of the sample increases with the increase of impact velocity (strain rate); When the impact velocity is similar (i.e., V = 7.0–8.0 m/s), the degree of macroscopic fragmentation of the sample increases as the real-time temperature increases. When the impact velocity is 6.0–9.0 m/s and the temperature is between 25 °C and 500 °C, the coal-series limestone samples are mostly fractured into several parts from the center after being subjected to impact load, and the shape of the fragments is prismatic. When the temperature is between 600 °C -800 °C, the degree of fragmentation of the sample increases, and the shape of the fragments is wedge-shaped. It can be obtained that when the temperature is greater than 600 °C, the initial damage of coal-series limestone increases significantly. When the impact velocity is between 9.0 and 10.0 m/s, the degree of fragmentation of the sample is significantly higher than that at the impact velocity of 6.0–7.0 m/s under the same temperature. From a macroscopic perspective, as the temperature increases, discerning the level of sample fragmentation becomes increasingly challenging. In this case, particle size screening can be used to calculate the average particle size of the broken fragments and the fractal dimension for quantitative analysis.

A grading screen was employed to screen the fragments into nine particle sizes: 0–5.0 mm, 5.0–7.0 mm, 7.0–9.0 mm, 9.0–11.0 mm, 11.0–14.0 mm, 14.0–17.0 mm, 17.0–20.0 mm, 20.0–30.0 mm, and ≥ 30.0 mm. The mass of fragments with different particle sizes was weighed, the percentage of the mass of blocks for each particle size to the overall mass (Wsn) was calculated, and the block size distribution coefficient r was defined to characterize the failure degree of the rock sample36 (Eq. 3). The larger the value ofr, the smaller the fragmentation degree of the sample; The smaller the value of r, the greater the fragmentation degree of the sample.

where dvn represents the average particle size of group n, which is the average of the maximum and minimum particle sizes within the particle size range (for example, in the group with a particle size of ≥ 30.0 mm, the average particle size is determined by taking the average of the maximum particle size measured by the fragments in that group and 30.0 mm). According to the given definition, r represents the average particle size of fragmented coal-series limestone after failure, and a smaller value of r indicates a higher degree of damage.

Figure 10 shows the variation of Wsn and r of blocks at different particle sizes with temperature T under the same external impact. It can be concluded that as the temperature increases, the proportion of fragments with a particle size > 30 mm changes significantly, showing a pattern of first increasing and then decreasing. When the temperature increases from 25 °C to 200 °C, the block size distribution coefficient r increases from 23.3 mm to 25.2 mm, with an increase of 8.17%.This indicates that as the temperature increases, the degree of fragmentation of the sample gradually decreases, meaning the sample’s integrity is better preserved. When the temperature increases from 200 °C to 800 °C, the block size distribution coefficient r decreases from 25.2 mm to 21.2 mm, with a decrease of 15.88%.It indicates that when the temperature exceeds 200°C, the degree of fragmentation of the sample gradually increases, meaning the sample’s integrity is progressively compromised. This phenomenon can be attributed to the thermal expansivity of the mineral components within the coal-bearing limestone and the physicochemical reactions at high temperatures. When the temperature rises from 25°C to 200°C, the mineral components in the sample undergo thermal expansion and gradually fill the natural pores and fractures. Changes occur in the microstructure and stress state of the coal-bearing limestone, leading to an increase in its strength and toughness. The fragmentation behavior exhibits a more concentrated trend, resulting in the formation of larger fragments. However, when the temperature exceeds 200°C, the mineral components within the coal-bearing limestone may begin to undergo processes such as thermal decomposition, melting, or phase transformation, causing a sharp decrease in the overall strength and stability of the rock. As a result, the rock becomes more susceptible to fragmentation under external forces, forming smaller particles.

Figure 11 shows the variation of Wsn and r of blocks with different particle sizes with strain rate \(\dot{\varepsilon }\) under real-time high temperature of 800 °C. As the strain rate increases, the block size distribution coefficient r decreases. When the strain rate increases from 46.74 s−1 to 65.35 s−1, the block size distribution coefficient r decreases from 24.0 mm to 23.6 mm, with a decrease of 1.67%; When the impact velocity increases from 65.35 s−1 to 86.67 s−1, the coefficient r rarely changes; When the impact velocity increases from 86.67 s−1 to 95.83 s−1, the coefficient r decreases from 23.6 mm to 21.2 mm, with a decrease of 10.17%.

The fractal dimension is positively correlated with the failure degree of sample, that is, as the degree of sample failure increases, the calculated fractal dimension also increases. At present, the calculation of fractal dimension is mostly based on mass equivalent size, such as Eqs. (4) and (5). Figures 12 and 13 show the variation patterns of \(\dot{\varepsilon }\)and \(\lg \left( {{{M_{R} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{M_{R} } M}} \right. \kern-0pt} M}} \right)\) with \(\lg R\) different temperatures T and strain rates.

In Eqs. 4 and 5, d is the slope of the double logarithmic fitting line, M is the mass of the rock sample, MR is the mass of the fragment whose diameter is less than the particle size R, and D is the fractal dimension of the rock fragment.

Figure 14 shows the variation of the fractal dimension D of the sample with temperature T under the same external impact. As the real-time temperature increases from 100 °C to 800 °C, the fractal dimension D shows a non-linear change pattern as the temperature increases. When the temperature is less than 600 °C, the growth rate of the fractal dimension D is small. When the temperature is greater than 600 °C, the growth rate significantly increases. This indicates that the degree of fragmentation of the sample under impact increases, and the temperature damage of the sample before impact increases.

Figure 15 shows the variation of fractal dimension D with strain rate \(\dot{\varepsilon }\) at a real-time temperature of 800 °C. As the strain rate increases, the fractal dimension D shows a non-linear increasing trend, and the fitting equation is obtained, as shown in Fig. 16. As the strain rate increases (the impact velocity increases), the impact energy received by the sample increases, resulting in an enhancement in the degree of fragmentation and the fractal dimension. The fractal dimension increases gradually with the increase of strain rate.

Microscopic damage and failure mechanisms

Microscopic morphology and structural characteristics of mineral components

The mechanical properties of materials are closely related to their mineral composition and internal structure. To analyze the influence of temperature on the mechanical properties of coal-series limestone, the advanced XRD, SEM and EDS were used to study the material composition and microstructure morphology characteristics of coal-series limestone under different temperature conditions.

Table 1 presents the elemental composition and mass proportion of mineral components in coal-series limestone under theoretical conditions. Figure 16a shows the microscopic morphology characteristics of the fracture surface of the sample after the impact at the magnification of 2000 under the temperature of 25 °C. The mineral at Position ① in Fig. 16b shows a thin stepped or layered structure. The results of EDS show that the mass proportions of C, O, Ca, and Si elements at Position ① are 8.4%, 46.3%, 44.4%, and 0.9%, respectively. Based on Fig. 1b and Table 1, it can be inferred that the mineral at Position ① is a calcite containing Si impurities. The mass proportions of C, O, Ca, and Si elements at Positions ② are 7.1%, 32.7%, 52.9%, and 3.2%; while those at Position ③ are 9.0%, 43.4%, 42.3%, and 2.5%, respectively. These minerals are inferred to be calcite containing impurities. Figure 16c shows the microscopic morphology characteristics of calcite in the rock sample at the magnification of 4000 times under the temperature of 25 °C. It can be seen that calcite exhibits a dense and irregular appearance without clear grain boundaries.

Figure 17a shows the microscopic morphology of the fracture surface of the sample after the impact under the temperature of 25 °C at the magnification of 1000. The morphological feature of the mineral at Position ① is prismatic, with clear edges and a smooth surface. As shown in Fig. 17b, the results of EDS elemental analysis show that the mass proportions of C, O, Mg, and Ca elements at Position ① are 12%, 55.2%, 12%, and 20.8%, respectively. Combined with Table 1, it can be determined that the mineral at Position ① is dolomite. Figure 17c shows the distribution of Mg, Al, and Si elements in Fig. 17a. It can be seen that the area covered by the Mg element in Fig. 17a has a prismatic morphology, or a well-defined and flat surface cross-section, which is consistent with the morphology of the mineral at Position. Therefore, these parts can be determined as dolomite and exist as a cluster of prismatic crystals. Figure 17d shows the microscopic morphology characteristics of dolomite crystals in the rock sample at the magnification of 4000.

Influence of real-time high-temperature and impact on mineral composition and microstructure characteristics

Dolomite is a complex salt of MgCO3 and CaCO3, and its thermal decomposition reaction chemical formula is shown in Eqs. (5)–(7)37. Studies have shown that the thermal decomposition temperature of MgCO3 in dolomite is about 600°C38. The main component of calcite is CaCO3, and its chemical reaction for thermal decomposition is shown in Eq. (7). The decomposition temperature is above 900 °C39. Therefore, it can be considered that calcite does not undergo decomposition in this experiment.

Based on the XRD analysis of the internal mineral composition of coal-series limestone at temperatures of 25 °C, 400 °C, 600 °C, and 800 °C in Fig. 18a–d, it can be concluded that when the temperature reaches 600 °C, the CaCO3 content in the rock increases significantly, while the content of dolomite (CaMg (CO3)2) decreases significantly. This indicates that some dolomite in the rock sample decomposes and the microstructure of the rock is changed, which enhances the initial damage caused by heating40. As shown in Fig. 18d, when the temperature rises to 800 °C, the CaCO3 content in the rock further increases, and the high-temperature chemical damage of the rock further intensifies. Therefore, when the temperature exceeds 600 °C, the peak strength of coal-series limestone shows a non-linear decreasing trend.

Figure 19a shows the elemental analysis results of calcite at 800 °C obtained by EDS. The mass proportions of C, O, Ca, and Si elements are 11.0%, 49.8%, 37.2%, and 2.0%, respectively. After high-temperature calcination at 800 °C, the mass proportions of C, O, and Ca elements in calcite have hardly changed, indicating that calcite has not undergone thermal decomposition. However, after being subjected to high-temperature calcination, more microcracks are generated in the calcite after impact, as shown in Fig. 19b. The high temperature caused changes in the physical and mechanical properties of calcite, resulting in a decrease in rock mechanical properties and a more severe degree of fragmentation during impact (calcite is in the square frame, with arrows pointing towards microcracks). Compared with Fig. 16c, it can be seen that the mechanical properties of the rock exhibit significant differences under the high-temperature impact than those under the room temperature impact.

Figure 20a shows the elemental analysis results of dolomite obtained by EDS. The mass proportions of C, O, Ca, Mg, Al, Si, and K elements are 5.0%, 49.3%, 27.2%, 12.6%, 1.8%, 2.6%, and 1.5%, respectively. It can be determined that dolomite contains impurities. After high-temperature calcination at 800 °C, the mass proportions of C and O elements in dolomite in coal-series limestone decrease, while the mass proportions of Ca and Mg elements increase, further indicating that part of dolomite undergoes pyrolysis. Compared with Fig. 17d, after being subjected to high-temperature impact at 800 °C, some edges of dolomite are passivated, and some crystals are granulated, resulting in the generation of micropores and microcracks inside, as shown in Fig. 20b. These are caused by the generation and escape of CO2 caused by thermal decomposition of dolomite, damaging the original structure of dolomite and reducing the mechanical properties of rock samples.

The peak strength of limestone exhibits a characteristic of initially increasing and then decreasing with the rise in temperature, reaching the maximum at around 300°C. This phenomenon can be explained as follows: In the natural state, limestone is primarily composed of three parts: mineral particles such as dolomite and calcite, free water and bound water, as well as primary pores and fractures. When the temperature is below 300°C, the free water gradually evaporates, and the mineral particles like dolomite and calcite expand upon heating, gradually filling the primary pores and fractures. This results in enhanced integrity of the limestone sample and a gradual increase in its strength. However, when the temperature exceeds 300°C, the strength of limestone gradually decreases. This is mainly attributed to two reasons. Firstly, high temperatures cause the continuous expansion of mineral particles like dolomite and calcite, leading to mutual compression among the particles and the gradual formation of new micro-cracks. Secondly, in a high-temperature environment, MgCO3 in dolomite undergoes thermal decomposition, producing CO2 that escapes, and some dolomite crystals gradually degenerate into fine particles, causing further damage to the limestone. In summary, the microscopic mechanism of strength changes in limestone under high-temperature conditions can be summarized as physical strengthening (25–300°C) and chemo-physical degradation (300–800°C).

Conclusions

-

(1)

The dynamic stress-strain curve of coal-series limestone under the real-time coupling effect of high temperature and impact exhibits an insignificant compaction stage, which is different from those after the sequential coupling effect of high temperature and impact (i.e., there is a cooling process between the high temperature treatment and the impact). This is mainly because there is no thermal impact damage to the rock under the real-time coupling. Under real-time coupling, as the impact velocity and temperature increase, the plastic characteristics of the dynamic stress-strain curve become more obvious, and the failure of the sample transitions from brittle failure to brittle-ductile failure.

-

(2)

Under the real-time coupling of high temperature and impact, the dynamic peak stress of coal-series limestone first increases and then decreases with temperature, showing an approximate quadratic function pattern. When the impact velocity is 6.0–7.0 m/s, the maximum dynamic peak stress appears at about 300 °C; When the impact velocity is between 7.0 m/s and 8.0 m/s, the maximum dynamic peak stress occurs at about 200 °C; When the impact velocity is 8.0–10.0 m/s, the maximum dynamic peak stress occurs at about 100 °C. The dynamic peak stress almost increases linearly with the impact velocity. The dynamic elastic modulus varies approximately in a quadratic function with temperature and impact velocity.

-

(3)

The main substances in coal-series limestone are calcite, dolomite, and muscovite. The microscopic morphology of calcite at room temperature is characterized by thin-stepped or layered morphology. When the temperature rises to 800 °C, it does not undergo thermal decomposition, but its physical and mechanical properties change. After real-time impact, the degree of crystal fragmentation increases and a large number of microcracks is generated. The microscopic morphology of dolomite at room temperature is characterized by a prismatic shape, clear and flat edges, and generally exists in clusters. When the temperature rises to 600 °C, more dolomite begins to undergo thermal decomposition, and the crystal edges become passivated, even resulting in a granulation phenomenon. Besides, more micro pores and micro-cracks are produced, which reduces the mechanical properties of the rock.the microscopic mechanism of strength changes in limestone under high-temperature conditions can be summarized as physical strengthening (25–300°C) and chemo-physical degradation (300–800°C).

Data availability

Some or all data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon rea-sonable request.

References

Li, W. & Sun, X. Key technologies and practices for safe, efficient, and intelligent mining of deep coal resources. Meitan Kexue Jishu/Coal Sci. Technol. (Peking). 52(1), 52–64 (2024).

Kang, H. et al. Mechanical behaviors of coal measures and ground control technologies for China’s deep coal mines – A review. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 15(1), 37–65 (2023).

Xie, H. et al. Study on the mechanical properties and mechanical response of coal mining at 1000 m or deeper. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 52(5), 1475–1490 (2019).

Xie, H. et al. Groundbreaking theoretical and technical conceptualization of fluidized mining of deep underground solid mineral resources. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 67, 68–70 (2017).

Hu, J. et al. Changes in the thermodynamic properties of alkaline granite after cyclic quenching following high temperature action. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 31(5), 843–852 (2021).

Su, C. et al. Effects of high temperature on the microstructure and mechanical behavior of hard coal. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 30(5), 643–650 (2020).

Xue, Y. et al. An experimental study on mechanical properties and fracturing characteristics of granite under high-temperature heating and liquid nitrogen cooling cyclic treatment. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 237 (2024).

Tripathi, A. et al. Experimental study on the quasi-static and dynamic tensile behaviour of thermally treated Barakar sandstone in Jharia coal mine fire region, India. Sci. Rep. 14(1) (2024).

Zhou, H. et al. Anisotropic strength, deformation and failure of gneiss granite under high stress and temperature coupled true triaxial compression. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16(3), 860–876 (2024).

Fan, L. F. et al. Evolution of mechanical properties and microstructure in thermally treated granite subjected to cyclic loading. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 47(4), 1431–1444 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. Experimental study of the mechanical properties and microscopic mechanism of carbonate rock subjected to high-temperature acid stimulation. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 237 (2024).

Hajiabadi, S. H., Khalifeh, M. & van Noort, R. Stability analysis of a granite-based geopolymer sealant for CO2 geosequestration: In-situ permeability and mechanical behavior while exposed to brine. Cem. Concr. Compos. 149 (2024).

Dong, X., Liu, S. & Liu, P. Study on mechanical properties and damage constitutive model of frozen sandstone under unloading condition. Yanshilixue Yu Gongcheng Xuebao/Chinese J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 43(2), 495–509 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Experimental study on crack evolution and strength attenuation of expansive soil under wetting-drying cycles. Nongye Gongcheng Xuebao/Transactions Chin. Soc. Agricultural Eng. 37(5), 113–122 (2021).

Bai, Y. et al. Study on the Mechanical Properties and Damage Constitutive Model of Frozen Weakly Cemented red Sandstone 171 (Cold Regions Science and Technology, 2020).

Sun, B. et al. Study on the Influence Law of Sand Production after Fracturing in Deep Sandstone Reservoirs (Springer Series in Geomechanics and Geoengineering, 2024).

Cheng, G. et al. Experimental study on brittle-to-ductile transition mechanism of lower silurian organic-rich shale in South China. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 170 (2023).

Yan, Z. et al. Experimental investigation of pre-flawed rocks under combined static-dynamic loading: mechanical responses and fracturing characteristics. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 211 (2021).

Yan, T., Yin, X. & Zhang, X. Impact toughness and dynamic constitutive model of geopolymer concrete after water saturation. Sci. Rep. 14(1) (2024).

Li, J. C. et al. An SHPB test study on stress wave energy attenuation in jointed rock masses. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2, 52403–52420 (2019).

Wang, P. et al. Dynamic properties of thermally treated granite subjected to cyclic impact loading. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 52(4), 991–1010 (2019).

Li, G. et al. Experimental study on Mechanical properties and failure laws of granite with artificial flaws under coupled static and dynamic loads. Materials 15(17) (2022).

Chen, X. et al. High strain rate compressive strength behavior of cemented paste backfill using split Hopkinson pressure bar. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 31(3), 387–399 (2021).

Duggal, R. et al. A comprehensive review of energy extraction from low-temperature geothermal resources in hydrocarbon fields. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 154 (2022).

Mends, E. A. & Chu, P. Lithium extraction from unconventional aqueous resources – A review on recent technological development for seawater and geothermal brines. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11(5) (2023).

Marzo, G. A. et al. Non-destructive radiological characterization applied to fusion waste management. Fusion Eng. Des. 173 (2021).

Liu, H. et al. Recent progress in radionuclides adsorption by bentonite-based materials as ideal adsorbents and buffer/backfill materials. Appl. Clay Sci. 232 (2023).

Tong, H. et al. A true triaxial creep constitutive model of rock considering the coupled thermo-mechanical damage. Energy 285 (2023).

Guo, X. et al. Deep seabed mining: frontiers in engineering geology and environment. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 10(1) (2023).

Zhao, Z. L. et al. Experimental Investigation on Damage Characteristics and Fracture Behaviors of Granite after high Temperature Exposure under Different Strain Rates 110 (Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, 2020).

Zhou, X. P., Li, G. Q. & Ma, H. C. Real-time experiment investigations on the coupled thermomechanical and cracking behaviors in granite containing three pre-existing fissures. Eng. Fract. Mech. 224 (2020).

Yuan, S. et al. Fracture properties and dynamic failure of three-point bending of yellow sandstone after subjected to high-temperature conditions. Eng. Fract. Mech. 265 (2022).

Mardoukhi, A. et al. Effects of heat shock on the dynamic tensile behavior of granitic rocks. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 50(5), 1171–1182 (2017).

Hao, Y. F. & Hao, H. Finite element modelling of Mesoscale concrete material in dynamic splitting test. Adv. Struct. Eng. 19(6), 1027–1039 (2016).

Wang, F., Frühwirt, T. & Konietzky, H. Influence of repeated heating on physical-mechanical properties and damage evolution of granite. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 136, 104514 (2020).

Guo, S. R. et al. Dynamic compressive mechanical property characteristics and fractal dimension applications of coal-bearing mudstone at real-time temperatures. Fractal Fract. 7(9), 695 (2023).

Samtani, M. et al. Isolation and identification of the intermediate and final products in the thermal decomposition of dolomite in an atmosphere of carbon dioxide. Thermochim. Acta (2001).

Xin, Y. et al. Acoustic emission (AE) characteristics of limestone during heating. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 147(23), 13725–13736 (2022).

Carlos, R. et al. Thermal decomposition of calcite: mechanisms of formation and textural evolution of CaO nanocrystals. Am. Mineral., 94(4): 578–593 .

Das, D., Mishra, B. & Gupta, N. Understanding the influence of petrographic parameters on strength of differently sized shale specimens using XRD and SEM. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 31(5), 953–961 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52074240, 52274140, 52304102 and 52174090), Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Science and Technology Major Program (No. 2023A01002), National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFC3804204).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P. Wu conceived and designed the research. Material preparation were performed by L. Zhang. Testing, data collection, and analysis were performed by Y. Zheng, M. Li, and B, Li. The first draft of the manuscript was written by L. Zhang and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, P., Zhang, L., Li, B. et al. Mechanical properties and microscopic damage characteristics of coal series limestone under coupling effects of high temperature and impact. Sci Rep 14, 32093 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83599-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83599-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Fracture propagation and water seepage behavior in overburden strata at Tunbao coal mine

Scientific Reports (2025)