Abstract

This paper had conducted tensile shear tests on single-lap joints (SLJs)bonded structures of carbon fiber reinforced resin matrix (CFRP) composite laminates with different overlap lengths, overlap widths, overlap model, adherend material, and adhesive layer thicknesses under two environments: room temperature dry state (RTD) and elevated temperature wet state (ETW). The failure modes were observed, and load–displacement curves were obtained. The microscopic morphology of the fracture surface was observed by scanning electron microscope (SEM). At the same time, a finite element simulation model was established to simulate the damage initiation and evolution process between layers and in the adhesive layer, and analyze the distribution laws of peel stress and shear stress in the adhesive layer. Through the combination of test data and simulation results, the influences of geometric parameters, material parameters and environmental parameters on the structure were explored, and the joint failure mechanism was revealed. Finally, the ACO-BP neural network was used to optimize the geometric parameters through test data. The research results showed that the geometric parameters of the structure mainly affect the bearing capacity and failure type. Reducing the overlap length and increasing the overlap width within a certain range can weaken the peeling phenomenon, so that a smaller overlap area has a higher shear strength. The material parameters of the adherend mainly affect the stress distribution law and stress transfer process of the adhesive layer in the overlap area. The joint mainly bore shear stress and peel stress, and shear stress is the main cause of damage initiation. When the types of adherend materials are different, the stress distribution law shows obvious asymmetric offset. The lap model mainly affects the location distribution of the failure area, and the environmental parameters mainly affect the area proportion relationship of various fracture forms in the mixed failure mode.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to their lightweight and high strength, carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) composite bonded components had been increasingly used in the aerospace and automotive industries. Currently, the two main priorities for the aviation and transportation sectors are cost savings and reducing environmental impact. Achieving these goals requires reducing structural weight, which can lower fuel consumption and improve payload efficiency. Two primary strategies for achieving lightweight structures are: 1) using low-density materials (composite laminates) for the airframe, and 2) replacing mechanical joints with adhesive bonding. Adhesive bonding had been widely applied in various industries, including aerospace, shipbuilding, and electronics. Compared to welding or bolted connections, adhesive joints not only reduce structural weight but also offer longer fatigue life and higher resistance to vibration and corrosion1,2,3,4,5,6. Single-lap adhesive joints (SLJ) had become the most widely used form of bonding due to their simplicity and ease of manufacture7. To determine joint strength and analyze the stress distribution and damage behavior of adhesives or adherends, many researchers had conducted extensive experimental testing, numerical simulations, and theoretical analyses in recent years8,9,10. Numerous studied focused on the failure of adhesive joints, comparing the effects of parameters such as overlap length, width, ply angle, and adhesive thickness on the performance and damage modes of bonded structures11,12,13. The studies conducted by Yang et al.14,15,16 all emphasized the complexity of the impact of environmental conditions on the mechanical properties of materials. They explored the liquid sensitivity of composite materials to alcohol and kerosene, as well as the relationship between the failure modes of structures and their service lives under seawater and ultraviolet aging conditions. P. Mohapatra17 compared the stiffness and load-bearing capacities of three different adhesive joint configurations, the study found that by increasing the bonding overlap length and adhesive layer thickness, the strength of the joint configurations can be increased. However, it results in a reduction in stiffness of the joint. Mao and Hu18,19 found, the ultimate failure load of composite laminate single-lap adhesive joints increases with the increase of lap length and tends to a stable value, the lap shear strength decreases with the increase of length. Subsequently, genetic algorithms are used to perform multi-objective optimization on the joints to improve structural performance. Zou20,21 investigated the failure process and characteristics of joints between dissimilar materials. Through research, it was discovered that damage initially occurs at the end of the composite material having relatively lower stiffness and then gradually spreads to the metal end. The finite element method (FEM) has also been widely applied in the analysis of adhesive joints22,23. Mu24 based on the Tsai-Wu strength criterion, proposed a novel stiffness degradation model for progressive damage simulation of typical laminated and solid composite structures. Campilho25 have used both standard and extended finite element models to predict the strength of single- and double-lap adhesive joints, evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of both methods. Noda et al.26 introduced a mesh-independent proportional method for calculating singular stress fields at dissimilar material interfaces, allowing for more accurate analysis of stress distribution at the interface edges of bonded joints. Metehri27 developed a 3D numerical model in Abaqus to evaluate how geometric changes in the adherends’ and adhesive edges affect the mechanical strength of a single—lap joint under uniaxial tensile stress. The results clearly demonstrate that a geometric modification at the two free edges of the two substrates can enhance the joint’s strength and alleviate the high stress concentrations within the adhesive.

In this paper, the tensile-shear testing of single-lap adhesive joints was carried out under multiple parametric conditions, the fuselage butt-joint single lap model, as a special joint mode, was put forward and compared with the traditional single-lap adhesive structure. During the research process, the parameters whose changes were controlled included the length and width of the lap, the material types of the adherends, the thickness of the adhesive layer, and the environmental conditions of the test. Through this comprehensive experimental approach integrated with SEM scanning technology, the stress—bearing process and fracture morphology of the specimens under different parametric conditions were observed. Meanwhile, the failure strength and load—displacement curves were obtained, facilitating a detailed analysis of the tensile failure modes and micromechanical characteristics of the single—lap adhesive structure. Subsequently, the finite element model (FEM) was developed for the single—lap joint, by comparing the simulation results with the experimental data, the validity of the finite—element model was verified, the stress distribution within the adhesive joints was further explored. In this model, the Hashin criterion and Continuum Damage Mechanics (CDM) were combined to accurately predict the initiation and evolution of in—plane damage within the laminate. Additionally, the Cohesive Zone Model (CZM) was cleverly utilized to simulate the delamination damage in the laminate and the failure of the adhesive layer. Finite element analysis allowed us to comprehensively understand the static behavior, failure mechanism, and complex damage evolution process during the tensile loading process. Finally, the ant—colony—algorithm—optimized back—propagation (ACO—BP) neural network was applied to optimize the geometric parameters. By integrating advanced computational intelligence with the mechanical analysis of adhesive joints, provided a reference for the optimization of the design of related structures.

Experimental method

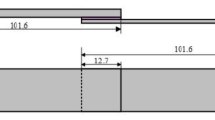

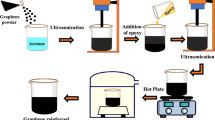

To assess the process stability and performance of adhesive bonding in typical structures, this study designed tensile-shear tests, considering the practical applications of these bonded joints in four parts of an aircraft: the wing, horizontal tail, vertical tail, and fuselage. The influence of various factors such as overlap length (L), overlap width (W), adhesive layer thickness (H), adherend material (P/F), specimen configuration (S), and environmental conditions room temperature dry state and elevated temperature wet state (R/E) were considered. The test matrix was shown in Table 1, with three specimens selected for each test group. The preparation process of the test specimens mainly followed the ASTM D5687/D5687M standard. The adherend materials were divided into two categories: prepreg laminate (UIN23100/9314) and carbon fiber fabric laminate (W-3021FF/LR285). The prepreg layup sequence is [09], labeled as P, while the fabric layup sequence is [(+ 45/-45) / (0/90)]2s, labeled as F. The adhesive used for bonding the laminates is a room-temperature-curing epoxy structural adhesive, composed of a resin mixture (LR285 + LH287), cotton powder, and fumed silica in a ratio of 100:11:6. The specimen models included single-lap shear test specimens (code S1) and fuselage butt-joint single-lap shear test specimens (code S2), with the dimensions shown in Fig. 1. The environmental conditions selected for testing include a dry state at room temperature (R) and a hot-humid state (E), where the hot-humid environment was maintained at 56°C and 85% relative humidity in the environment box (MQ-T1050F-1N) until moisture equilibrium was reached. The process of moisture absorption aging treatment for the specimens complied with the ASTM D 5229/D 5229 M—14 standard.

To minimize the influence of loading eccentricity and prevent damage at the gripping ends during loading, reinforcement tabs were applied at the gripping ends, with a reinforced region length of 25.4 mm. The tensile-shear tests were conducted on an electro-hydraulic servo fatigue testing machine (INSTRON-8801, USA), with the experimental setup shown in Fig. 2. Prior to the test, the actual dimensions of the lapped portion of each specimen were precisely measured, and the lap area was subsequently calculated. Subsequently, the specimen was carefully mounted and clamped onto the tensile testing machine, with each chuck of the machine firmly gripping the spacer. The loading operation was then carried out at a loading rate of 1.27 mm/min. A load sensor was used to collect load and displacement data to draw a curve. The average ultimate load for each group of adhesive joints was calculated, and the maximum shear stress (in MPa) was determined by dividing the ultimate load by the actual overlap area.

Experimental results

Figures 3a and b had illustrated the trends in average tensile-shear strength of adhesive joints under tensile loading, as a function of overlap length and width, for different experimental parameter configurations. The results showed that among the 16 groups of test specimens, the 0.5-FF-S1-E-L12-W50 group had exhibited the highest tensile-shear strength, reaching 18.69 MPa. Compared to the specimens with overlap widths of 30 mm and 40 mm, the strength had increased by 42.45% and 40.21%, respectively, indicating a significant phase of rapid strength improvement with increased width. In contrast, when analyzing the tensile-shear strength of the same group in a dry environment, it was observed that the strength increase had occurred in the initial phase of increasing width from 30 to 40 mm, followed by a strength reduction as width increased further. This phenomenon illustrated that the high—temperature and humid environment was a complex influencing factor. While it boosted the ultimate strength of the specimens on the whole, it had a negative impact on those with smaller widths by reducing their tensile—shear strength and thus weakening their resistance to failure. The difference in the trend of this strength variation merited further investigation. It might have been associated with the interaction mechanism between the adhesive and the adherend within the high—temperature and humid environment. For instance, humidity could have altered the molecular structure of the adhesive or the bonding state of its surface with the adherend, and this effect was more conspicuous particularly for specimens with smaller widths. When the contact area is relatively small, humidity can permeate the bonding interface more readily, thus inflicting more prominent damage on local chemical bonds and intermolecular forces. Moreover, high temperatures might accelerate the thermal aging process inside the adhesive, rendering it more susceptible to performance deterioration in specimens with smaller widths and consequently influencing the strength. For the fuselage butt-joint single-lap shear specimens (S2), variations in overlap length and width had little effect on ultimate strength, with fluctuations in strength ranging between 5 and 11% due to length and between 13 and 18% due to width. This phenomenon manifested that this type of joint possessed certain specificities in its structure and exhibited lower sensitivity to the geometric and environmental parameters within the bonding region. This stability was likely to originate from the design characteristics of the fuselage butt—joint single—lap structure per se. It was capable of withstanding, to some degree, the impacts resulting from the variations in geometric parameters and environmental factors, thereby better preserving strength stability and environmental resistance. This property was of great significance in practical engineering applications, signifying that this type of joint could still operate reliably in complex service environments and under conditions of certain geometric dimension variations, making full use of the inherent properties of the composite laminates and reducing the risk of structural failure due to external factors. For specimens with an adhesive layer thickness of 0.5 mm, two groups of specimens with different adherend materials (PF/FF) had shown similar trends in strength variation with length, both decreasing as the length increased. However, the PF specimens had exhibited a plateau in strength during the length variation, while the FF specimens had displayed a gradual decrease. The trend in tensile-shear strength with respect to width had differed between the two groups, particularly in the smaller width range. The PF specimens had shown a decrease in strength with increasing width, while at larger widths, the differences between the two groups’ trends had diminished, and strength had begun to increase again. This complex variation relationship implied that the influence of width on the bonding performance of different adherend materials was nonlinear, which might involve the stress—transfer mechanism between materials and adhesives as well as the differences in deformation modes of materials under different widths. For the FF adherend material, comparing the two groups with adhesive layer thicknesses of 0.5 mm and 1.0 mm, the 0.5 mm specimens had consistently demonstrated higher strength across all test configurations. As the adhesive thickness increased, plastic deformation along the longitudinal tensile direction of the adhesive layer had accelerated, resulting in higher interfacial stress. Furthermore, the strength trends with increasing width were entirely opposite between the two thickness groups.

According to ASTM D5573 standard, the failure of composite adhesive bonded structure was divided into four categories, cohesive failure, adherend failure, adhesive failure (adhesive-adherend interface failure) and mixed failure (the aforementioned three failure modes), as shown in Fig. 4. Among them, the failure of composite base material could be further divided into fiber failure, matrix failure and interlaminar delamination failure. After the test, the peel failure surface of the specimen was observed. Six groups of characteristic test pieces were selected for fracture morphology analysis. The classification of test pieces and fracture photos were shown in Fig. 5. By comparison, it was found that the high-temperature wet environment parameters set in the test had no significant impact on the failure mode of the adhesive joint. Instead, it mainly affected the proportion of lap area occupied by various failure modes. The fracture of Fig. 5a and b showed a mixture of three modes: cohesive failure in the adhesive layer, fiber tearing failure and interlaminar failure of composite material. Among them, the cohesive failure in the adhesive layer presented an arc distribution at the adhesive edge. The surface of the cohesive failure area was smooth and there were no obvious scaly patterns. This indicated that cohesive failure might be caused by the gradual expansion of the weak areas within the adhesive during the tensile process. The cohesive failure area of the dry test piece was smaller and the boundary inclination angle was closer to 45°. Fiber shear fracture occurred in both the upper and lower panels at the middle position of the adhesive. This showed that during the stretching process, the fibers endured relatively large shear stress. It might have been because the stress was concentrated in this area or the coordinated stress—bearing mechanism between the fibers and the adhesive had changed at this part. At the same time, due to different delamination numbers in the upper and lower panels caused by interlaminar failure, the fracture presented a step shape. The differences in mechanical properties between different layers and the non—uniform distribution of inter—layer stress might have been the reasons for this phenomenon. The main failure form of Fig. 5c and d was thin-layer cohesive failure. The fracture pattern of the cohesive failure area of the test piece in dry environment was rougher, and slight fiber tearing occurred along the 0° fiber direction at the adhesive edge on one side of the unidirectional prepreg panel. It was indicated that the interfacial bond between the fiber and the adhesive in this area was damaged to a certain extent during the tensile process, and it might be caused by factors like improper interface treatment during the preparation process. There was a local hole-type adhesive failure area in the middle of the adhesive, this might be because air holes were generated in the adhesive during the curing process or local stress concentration during the usage process led to the separation between the adhesive and the adherend. Figure 5e and f was interlaminar fracture of composite material, that is, delamination failure. The delamination range was directly affected by the interlaminar mismatch angle. Slight fiber tearing occurred accompanied by a small amount of through-thickness fracture near the turning lap position. The adhesive layer was intact and there was no adhesive failure between the adhesive layer and the adherend in the test piece. The failure form of the adhesive joint obtained from the test was relatively ideal, indicating that the connector had fully utilized the strong bearing capacity of the adhesive. Table 2 showed the fracture patterns that had been observed for different specimens tested under different mixed—mode ratios along with the contribution of each fracture pattern obtained using image processing.

Considering the varying contributions of different fracture modes to failure behavior, this study had employed scanning electron microscopy (SEM3100) to characterize post-fracture specimens and analyze their fracture behavior in conjunction with bonding parameters, the result was shown in Fig. 6. For Fig. 6a, the SEM results had revealed step-like fracture surfaces caused by fiber shear failure and partial resin fracture. The resin fracture surface had exhibited a comb-like pattern, with the orientation of the pattern aligned with the propagation direction of interlayer cracks, indicating the occurrence of Mode II interlaminar shear failure. Cohesive failure regions had displayed a smooth surface with shallow river-like patterns, where the flow direction had corresponded to the fracture direction. Visible bubble defects within the adhesive had led to stress concentration in the adhesive layer, reducing load-bearing capacity and resulting in cohesive failure. Figure 6b had shown irregular failure patterns at the adhesive interface, with the appearance of coiled macromolecular structures. It showed that under the action of tensile and shearing forces, the macromolecular chains of the adhesive had been deformed and entangled. The fracture surfaces in the dry state were rougher, and the small cracks had exhibited more pronounced bending deformation, suggesting that the failure mode was ductile fracture within the structural adhesive. Additionally, at the adhesive edge, localized 0° fiber shear fractures were observed, accompanied by river-like patterns in the resin matrix and evidence of plastic flow. It was indicated that during the failure process, the energy absorption and deformation processes were also participated in by the resin matrix, and the overall mechanical properties of the bonded joint were closely related to its flow characteristics. For Fig. 6c, SEM observations had revealed that a majority of the resin had covered the fiber surfaces, with no distinct interface visible. The comb-like resin pattern was indicative of interlayer delamination, while localized matrix fractures had caused fiber-matrix separation, characteristic of intralaminar failure. Matrix fragmentation was observed in the transition region of the bonded joint, leading to fiber fracture in the 45° direction.

Finite element model

A three-dimensional finite element model of the single-lap joint specimen for composite materials was established using the ABAQUS finite element analysis software. The boundary conditions were set so that one end of the bonded structure was fully constrained with fixed support at the nodes, while the other end was coupled to a reference point using a coupling constraint to ensure that the relative position between the reference point and all nodes on the end surface remained constant. A uniform tensile load was applied at the reference point, and all degrees of freedom, except in the tensile direction, were constrained at the loading end. During the analysis steps, the x-direction displacement and reaction forces at the reference point were selected for output. A tie constraint was applied between the adhesive layer and the composite laminate. To more accurately simulate the failure process, mesh refinement was performed in the overlap and adjacent regions, as shown in Fig. 7. The composite laminate was modeled with a thickness of 0.25 mm per ply, and the corresponding material properties and fiber orientations were assigned to each mesh layer using the “Composite Layup” feature. To ensure calculation accuracy, an 8-node reduced integration element (C3D8R) was used for the laminate, and 3D cohesive elements (COH3D8) with thicknesses of 0.5 mm and 1.0 mm were used for the adhesive layer. A zero-thickness cohesive element was inserted between the two adjacent plies near the adhesive layer to predict the onset and propagation of delamination in the laminate. The zero-thickness adhesive layer was also modeled using 3D cohesive elements (COH3D8). To ensure convergence in the finite element analysis, the adhesive layer was discretized with only one mesh layer through the thickness, and a viscosity coefficient of 0.0001 was added to the cohesive elements to improve computational convergence. The establishment of cohesive elements is based on the bilinear constitutive model28. Combined with the B-K fracture criterion, the quadratic nominal stress criterion is applied to simulate the material degradation of the adhesive layer. The material parameters for the laminates and adhesive layers are listed in Table 3 ref.29,30.

Joint failure load analysis

The six characteristic specimens (labeled A-F) were selected based on the post-experiment failure modes. They had been tested in a dry environment. Respectively, A:1.0-FF-S1-W25-L50, B:0.5-FF-S1-W50-L12, C: 0.5-PF-S1-W25-L65, D:0.5-PF-S1-W20-L12; E:1.0-FF-S2-W25-L30; F:1.0 FF-S2-W30-L12, with their load–displacement curves were shown in Fig. 8. The curves indicated that the finite element simulation results aligned closely with the experimental data, demonstrating that the finite element model, established using the progressive damage analysis method and cohesive zone model, had accurately simulated the behavior of composite adhesive joints under uniaxial tensile loading. The six specimens had finite element predicted failure loads of 7065 N, 9355 N, 12,710 N, 4047 N, 4058 N, and 2983 N, respectively. The corresponding experimental average failure loads were 7445 N, 9606 N, 11,080 N, 4371 N, 3505 N, and 2750 N. The discrepancies between the simulated and experimental results were 5.1%, 2.6%, 14.7%, 7.4%, 15.1%, and 8.4%, respectively, indicating a high degree of correlation between the simulations and the experimental results. From the curves, it was observed that when the overlap length L = 12mm, the load curve of the specimen was more stable, and the simulation results were in closer agreement with the experimental data. However, as the overlap length increased, the experimental ultimate load exhibited more significant instability and fluctuations, leading to larger discrepancies between the experimental and simulated results. These deviations were likely caused by the presence of bubbles at the adhesive interface. Furthermore, the larger the overlap length and width, the higher the probability of defects in the adhesive layer.

Joint stress analysis

During the tensile loading of single-lap joints, secondary bending effects occurred, causing displacement in the overlap plates along the thickness direction, reaching maximum values at the ends, which resulted in deformation of the adhesive layer and the generation of stress. As the load increases, this bending effect became more pronounced and eventually led to the load-bearing failure of the adhesive layer. Even in joints with stiffness imbalances, secondary bending persisted under tensile loads. Due to the stiffness differences between the overlap plates, the overall displacement and adhesive layer stress exhibited an asymmetric pattern, meaning that damage initiation and propagation tended to begin at one end first. The stress contour plots for the six tested specimens just before damage initiation were shown in Fig. 9. To visually highlight the bending mode, the deformation scale was appropriately magnified during post-processing of the finite element results. For specimens A and B, the overall stress distribution and that of the adhesive layer exhibited a clear symmetry, with stress in the adhesive layer mainly concentrated near the edges on both ends. For specimens C and D, the stress contour plots showed that the adhesive layer attached to the stiffer end of the composite fabric overlap plate experienced greater stress during the loading process compared to the other end, and the adhesive elements at this end entered a damaged state earlier, eventually leading to failure. In specimens E and F, due to the particular overlap configuration, the stress was primarily concentrated in the transition area of the overlap, with relatively lower stress distributed across the adhesive layer.

Stress distribution and evolution analysis of adhesive layer

The uneven stress distribution in the adhesive layer, caused by the bending of the overlap plates, played a significant role in determining the ultimate load-bearing capacity of the bonded structure. In this finite element analysis, special attention was given to the stress distribution in the adhesive layer. A path was created along the midline of the adhesive layer through the nodes of the mesh, and three representative loading steps (step = 1, 2, 3; example: A1 means initial damage time of specimen A, A2 means the intermediate time of damage of specimen A; A3 indicates the time when specimen A is about to fail) were selected to analyze the shear stress and normal stress along this path from the moment before adhesive damage to the point of complete structural failure. Figure 10 showed the peel stress distribution curve S33 and shear stress distribution curve S13 of the adhesive layer, and the horizontal coordinate x/OL indicates the relative position of the cell in the length direction of the adhesive layer (x is the element position and OL is the overlap length). Overall, when the adhesive layer is symmetrically positioned in the middle of the top and bottom overlap plates, the bending moments at both ends are equal, resulting in a symmetric stress distribution. As seen in Figs. 10a and c, as the load increases, the S33 stress at both ends of the adhesive layer gradually decreased. As the specimen approached failure, the peak stresses shifted toward the middle and rapidly declined, with the abrupt drop in stress more pronounced in specimens C and D. In the central region of the adhesive layer, the peel stress remained relatively low and in compression. As damage propagated, the absolute value of S33 in this region increases. Stress concentration at the ends of the adhesive layer made these regions high-risk zones for failure, confirming that damage initiation began at the ends and propagated along the x-axis toward the center. Additionally, asymmetrical shifts in the peel stress curves in specimens C and D, caused by differences in adherend material, were clearly visible, with the peak stress values skewed to the right. Comparing specimens A and B, it was evident that when the adhesive layer thickness is 1 mm, the S33 peak is higher than that of the 0.5 mm thick adhesive layer. Considering that the peel stress in the adhesive layer is governed by the bending deflection of the laminate, the thicker adhesive layer exhibited greater plastic strain, faster damage propagation, higher interface stress, and was more prone to failure. Furthermore, the smoother transition at the S33 peak in specimens B and D, compared to A and C, suggested that the stress concentration in the adhesive layer was alleviated when the overlap length is 12 mm. Figure 10e showed that for specimens E and F, due to the specific overlap configuration, the peel stress distribution in most of the adhesive layer fell within the 0–5 MPa range. A sudden stress shift occurred at the right edge of the overlap, indicating that the adhesive layer was not the weakest part of specimens E and F, allowing the composite material’s strength properties to be better utilized.

The peel stress S33 and the shear stress S13 distribution of adhesive at different loading points, (a) S33 of 1.0-FF-S1-W25-L50 and 0.5-PF-S1-W25-L65;(b) S13 of 1.0-FF-S1-W25-L50 and 0.5-PF-S1-W25-L65; (c) S33 of 0.5-FF-S1-W50-L12 and 0.5-PF-S1-W20-L12;(d) S13 of 0.5-FF-S1-W50-L12 and 0.5-PF-S1-W20-L12; (e) S33 of 1.0-FF-S2-W25-L30 and 1.0-FF-S2-W30-L12; (f) S33 of 1.0-FF-S2-W25-L30 and 1.0-FF-S2-W30-L12.

Figure 10b and d illustrated the variation in shear stress S13 in the adhesive layer as the load increases during the damage process for specimens A, B, C, and D. The curves for specimens A and B showed relatively symmetric distributions, with the peak S13 stress remaining nearly constant throughout the loading process. The peak stress locations shifted from the ends toward the center. Comparing specimen B with A, it was observed that the reduction in stress at the bonded edges and the increase in stress in the central region were more gradual in specimen B. This indicated that increasing the width of the specimen can effectively alleviate stress concentrations. When comparing the curves of specimens A and C, it was evident that longer overlap lengths resulted in a low-shear-stress region in the middle of the adhesive layer. The longer the overlap length, the more extended this low-stress plateau became. However, the adhesive layer’s load transfer primarily relies on the high-stress regions near the edges of the overlap zone, meaning that the shear stress extremes did not decrease with an increase in overlap length. For specimen D, no distinct stress peaks were observed during the adhesive layer failure process. Instead, the entire adhesive layer maintained a relatively uniform high-stress state. Therefore, shear stress S13 played a more significant role in the failure of specimen D, where the persistent high-stress condition reduced the specimen’s load-bearing capacity, leading to rapid failure. In specimens E and F, the shear stress exhibited a fluctuating and increasing trend from left to right. Compared to peel stress, shear stress S13 had a noticeably greater impact on the behavior of specimens E and F.

Cohesive damage evolution analysis

The cohesive elements between the composite laminate and adhesive layer are characterized by two key damage parameters, QUADSCRT and SDEG, which are used to monitor the failure and degradation of the adhesive layer. These parameters allow for the investigation of crack initiation and damage evolution processes, primarily governed by peel adhesion failure. Both QUADSCRT and SDEG take values between 0 and 1, where a QUADSCRT value greater than 0 indicates the onset of initial damage, and when QUADSCRT reaches 1, it signifies that a crack has formed, and adhesive damage has begun. When the SDEG is greater than 0, it indicates the initiation of failure propagation, although the joint has not yet lost its load-bearing capacity, and the load has not yet reached its peak. As damage accumulates and the area of the damaged region in the adhesive layer grows, the imbalance between the damaged and undamaged regions causes the load-bearing capacity of the joint to decrease sharply, leading to the rapid failure of the adhesive structure. When SDEG reaches 1, it indicates that the stress has dropped to zero, and the cohesive elements have completely failed, losing their load-bearing capacity. This meets the B-K criterion, indicating that the delamination cracks in the adhesive layer have fully propagated. In ABAQUS finite element analysis, at this point of complete failure, the cohesive elements are deleted from the solution.

Figure 11 illustrated the degradation progression of the adhesive layer elements (from the start time of structural damage to the complete failure time respectively). For specimens A and B, symmetric failure of the adhesive layer elements first occurred on both sides of the adhesive layer. As the load increases, the degradation extends toward the central axis of the adhesive layer. In specimens C and D, due to differences in the adhered materials, the adhesive layer degradation contour plots exhibited asymmetry. In the initial failure stages of specimen C, localized damage first appeared on the right side of the adhesive layer at the edge of the fabric panel, evolving rapidly in a wave-like pattern toward the other side of the adhesive layer. As the damaged area accumulated, the load-bearing capacity of the joint decreased, confirming the progressive failure of the joint. Under applied load, most of the adhesive elements in the middle of specimens A and C experienced damage, with more than half of the elements undergoing varying degrees of stiffness degradation in the tensile direction. The peel stress caused by secondary bending led to continued damage propagation. After reaching a certain extent, even a small additional load caused the joint to fracture instantaneously, leading to complete failure. Therefore, it is crucial to avoid operating near the joint’s ultimate load during service and to moderately increase the stiffness of the laminate to reduce peel forces in the adhesive layer, ensuring safe operation. In specimen D, the damage distribution in the adhesive layer formed an "X" pattern. Due to the shorter overlap length, the stress imbalance and asynchronous damage—resulting from stiffness mismatch—were minimized. Additionally, considering the angle of the first ply of the composite material adjacent to the adhesive layer, it was observed that the damage morphology of shorter overlap specimens was significantly influenced by the ply orientation. For specimens E and F, the majority of the adhesive layer elements remained intact, with no significant stiffness reduction or element failure observed.

At the same time, Fig. 11 illustrated the delamination damage between the upper and lower laminate layers. For specimens A and C, the delamination damage in the lower laminate formed a flame-like shape at the edges of the adhesive joint, with specimen C exhibiting a more elongated damage region. Combined with the adhesive layer failure contour plots, this indicated that during tensile loading, the joint first experienced fiber delamination and shear fracture. Subsequently, under the combined effects of peel stress and shear stress, the damage propagated obliquely toward the adhesive layer interface, leading to cohesive failure. The delamination failure areas in both groups aligned well with the failure morphologies observed in the experiments. In contrast, specimens B and D exhibited relatively small delamination damage areas, with no significant evolution of damage observed as the load increased. For specimen B, only small localized areas of delamination were observed at the four corners of the overlap edges, with minimal delamination failure. However, in specimens E and F, interlayer damage was significantly more severe, with large areas of element deletion occurring in the transition regions of the lower laminate. This indicated adhesive failure between the layers of the laminate, leading to delamination. At this stage, the adhesive layer between the upper and lower laminates remained largely undamaged, suggesting that the unique overlap configuration effectively mitigated stress concentration in the adhesive layer during tensile loading, allowing the composite material to better utilize its high-strength properties.

Optimal design of bonding size

Based on the BP neural network, the overlap length and width were optimized under different parameter conditions, and the weights and thresholds of the BP neural network were optimized using the ant colony algorithm. The optimized ACO-BP neural network has better generalization ability and prediction accuracy, and it can more accurately deal with complex data sets. The neural network model is mainly composed of input, hidden and output layers, each layer consists of multiple neurons, which are connected to each other by connections with weights, the logical framework is shown in Fig. 12, and the algorithmic flow of the optimized ACO-BP neural network is shown in Fig. 13. The information is passed forward from the input layer in the network, calculated and transformed through the activation function of each layer, and finally reaches the output layer. In the actual optimization search process, the number of hidden layers is determined as

where Ni is the number of input neurons; \({N}_{0}\) is the number of output neurons; \({N}_{0}\) is the number of samples in the training set; and \({N}_{0}\) is a self-taking variable that usually takes the range of2,10.

Before parameter optimization, firstly, the number of ants was initialized to 90, the number of ant moves was 50, the pheromone volatility coefficient was 0.9, the transfer probability was 0.2, and the maximum number of iterations was 100. Secondly, the range of values of input variables was set to construct the solution space. For overlap model S1, the overlap length range was taken as [12,50] and overlap width range was taken as [25, 50] when the sticky object was FF, and the overlap length range was taken as [12,65] and overlap width range was taken as [25, 65] when the sticky object was PF; and for overlap model S2, the overlap length range was taken as [12,40] and overlap width range was taken as [25, 40] when the sticky object was FF. The width of the overlap was taken as [25, 40]. Finally, the target output was set according to the existing data and the actual situation, and the target output could be adjusted repeatedly according to the optimization results.

During the optimization process, ants with good performance (i.e., ants with small prediction errors) left more pheromone on their travel paths, and the ants chose the direction of the next move based on the pheromone concentration, i.e., adjusting the weights and thresholds. The movement and pheromone updating steps of the ants were repeated until the maximum number of iterations was reached or other termination conditions were satisfied. At the end of the iteration, the path with the highest pheromone concentration was selected as the optimal solution, i.e., the optimal BP neural network weights and thresholds combination was obtained. Since environmental factors (RTD and ETW) had a minimal impact on the mechanical properties of bonded joints, there were not taken into account when optimizing the dimensions. The optimization results of the length and width of the overlap joint under different conditions and the calculation results of the tensile shear strength of the finite element simulation model established according to the optimized geometric parameters were shown in Table 4.

Conclusion

-

(1) The results of tensile shear tests on composite single-lap bonded structures showed that the overlap lengths, overlap widths and adhesive layer thicknesses mainly affected the bearing capacity and failure types of specimens. The shear strength of specimens did not monotonically change with size, and there was basically no adhesive failure, indicating a relatively ideal bonding effect. The elevated temperature wet state mainly affected the proportional relationship of various failure modes in the overlap area, but had little effect on the bearing capacity of the specimen. The fuselage butt-joint single-lap shear test specimens(S2) maintained stable bearing capacity in the face of changes in geometric and environmental parameters. Combining macroscopic and microscopic fracture morphologies, the relationship between resin matrix patterns, fiber fracture directions and crack propagation paths, joint failure modes was summarized.

-

(2) Through comparative analysis of tests and simulations, the effectiveness of cohesive elements combined with stress criteria and energy criteria for simulating the strength of bonded structures was verified. Simulation results showed that under tensile load, peel stress and shear stress were mainly concentrated at both ends of the overlap area, which was the starting position of failure. Among them, shear stress played a leading role in the damage of the adhesive layer. For specimens with different types of upper and lower panel materials, due to the imbalance of stiffness, as the load increased, there would be obvious unequal end stresses and asynchronous stress peak migrations in the adherend layer.

-

(3) The simulation model used QUADESCRT and SDEG two parameters to explore the bonding failure damage evolution process. It was observed that the initial damage area and damage evolution process of the joint were greatly affected by geometric parameters, which in turn led to the emergence of mixed failure modes of different combination types. Among them, for the fuselage butt-joint single-lap shear test specimens, large-area interlaminar delamination fractures occurred in the turning transition area of the lower panel until the specimen completely failed. The adhesive layer in the overlap area remained basically intact, which could better exert the performance of composites themselves.

-

(4) Based on the extreme value of tensile shear strength, the ACO-BP neural network was used to optimize the joint size parameters, and the optimized results of overlap length and width under different conditions were obtained, providing a reference for size design in practical engineering.

Data availability

All relevant data that support the findings are available within this article and the Supplementary Materials.

References

Liu, B., Han, Q., Zhong, X. P. & Lu, Z. X. The impact damage and residual load capacity of composite stepped bonding repairs and joints. Compos Part B-Eng. 158, 339–351 (2019).

Ji SD, Cui X, Ma L, Liu H, Zuo YY, Zhang ZQ. Achieving high-quality aluminum to copper dissimilar metals joint via friction stir double-riveting welding. Acta Metallurgica Sinica(English Letters). 36(4):552–572, (2023).

Nian, S. Q. et al. A novel seal-flow multi-vortex friction stir lap welding of metal to polymer matrix composites. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 37(1), 451–462 (2024).

Zhang ZQ, Gong P, Ji SD, Ma L, Jin C, Li XY, Song Q, Achievement of superb-strength lap joint via opposite-directions flowing friction stir lap welding of 2024 aluminum alloys. Chinese J. Aeronautics. (2024).

Wu, Z. J., Xia, L., Wang, S. T. & Shi, T. L. Topology optimization of hierarchical lattice structures with substructuring. Computer Method Appl M. 345, 602–617 (2019).

Zhang, Z. Q. et al. Enhanced formation quality and tensile shear load of 7B04 aluminum alloys lap joint by impacting flow friction stir lap welding. J. Market. Res. 30, 5096–5108 (2024).

Sun, L. G., Ying, T., Hou, Y. L., Lu, X. X. & Li, C. Prediction of failure behavior of adhesively bonded CFRP scarf joints using a cohesive zone model [J]. Eng. Fract. Mech. 228, 106897 (2020).

Zhao X, Lu GY, Peng XB, Zhang NN, Qin JB. Fatigue life prediction of complex aeronautical components based on damage mechanics. Chinese journal of applied mechanics. 37(3):1007–1012. (2020).

Eslami, G., Yanes-Armas, S. & Keller, T. Energy dissipation in adhesive and bolted pultruded GFRP double-lap joints under cyclic loading. Compos. Struct. 248, 112496 (2020).

Cheng, X. Q., Zhang, Q., Zhang, J., Guo, X. & Niu, Z. R. Parameters prediction of cohesive zone model for simulating composite/adhesive delamination in hygrothermal environments. Compos. B Eng. 166, 710–721 (2019).

BARROSO A ,MALIN JC ,MANTIC V , París F. Premature failures in standard test specimens with composite materials induced by stress singularities in adhesive joints. Int. J. Adhesion Adhesives. (2020).

Kupski, J., Teixeira de Freitas, S., Zarouchas, D., Camanho, P. P. & Benedictus, R. Composite layup effect on the failure mechanism of single lap bonded joints. Compos. Struct. 217, 14–26 (2019).

Sulu, I. Y. Mechanical behavior of composite parts adhesively jointed with the insert double-lap joint under tensile load. Welding World 62(2), 403–413 (2018).

Yang, K. et al. The effects of environments and adhesive layer thickness on the failure modes of composite material bonded joints. Sci Rep 14, 22776 (2024).

Ghabezi, P. & Harrison, N. M. Multi-scale modelling and life prediction of aged composite materials in salt water. J. Reinforced Plastics Compos https://doi.org/10.1177/07316844231160189 (2023).

Gualberto, H. R. Reis, J. M. L. dos. Andrade, M. C. de. Costa, H. R. M. Faria, D. de S. Hunt, J. D. Amorim, F. do C., Investigation of the degradation over steel/GFRP single lap joint: UV radiation and immersion at different temperatures,Composite Structures, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2024.118590, (2025).

Mohapatra, R., Sonwani, H., Sidhardh, S., Narayanamurthy, V. & Ramji, M. An energy-based 2D model for predicting mechanical behavior of adhesively bonded CFRP laminates. Eng. Fail. Anal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108589 (2024).

Mao Z G, Hou Y L, L C, T Y, Sun L G. Effect of lap length and stacking sequence on strength and damage behaviors of adhesively bonded CFRP composite laminates. Acta Material Compositae Sinica. 37(1):121–131. (2020).

Hu C X, Hou Y L, L C, L C, Mao Z G. Influence of Different Bonding Parameters on the Strength of CFRP Laminates with Single Lap Bonding Structure and Optimization. J. Mech. Eng. 57(8):154–165. (2021).

Zou, T. C., Li, L. H., Liu, Z. H., Fu, J. & Qin, J. X. Experimental and Simulation Analysis of Ti-AFRP Adhesive Joint Failure Process. Plastics 50(2), 58–63 (2021).

Zou, T. C. et al. Failure Modes of Titanium Alloy-Aramid Fiber Composites Single Lap Joints. Polymer Mater. Sci. Eng. 36(8), 109–115 (2020).

Ribeiro, F. L., Borges, L. & Dalmeida, J. R. M. Numerical stress analysis of carbon-fibre-reinforced epoxy composite single-lap joints. Int. J. Adhesion Adhesives. 31(5), 331–337 (2011).

Da Costa, M. H. S., Sampaio, E. M. & Monteiro, A. H. Static failure analysis of adhesive single lap joints. Int. J. Adhesion Adhesives. 31(6), 446–454 (2011).

Mu, W. L., Na, J. X., Qin, G. F., Tan, W. & Shen, H. Effect of alternating load on residual strength of adhesively bonded CFRP composite-aluminum alloy joints. Acta Materiae Compos. Sinica. 36(5), 1121–1131 (2019).

Campilho, R. D. S. G., Banea, M. D., Pinto, A. M. G., Silva, L. F. M. & da, Jesus A.M.P. de,. Strength prediction of single-and double-lap joints by standard and extended finite element modelling. Int. J. Adhesion Adh. 31(5), 363–372 (2011).

Noda, N. A., Chen, D., Zhang, G. & Sano, Y. Single-fiber pull-out analysis comparing the intensities of singular stress fields (ISSFs) at fiber end/entry points. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 165, 105196 (2019).

Metehri.A, Madani.K, Campilho. D.S.G. Raul., Numerical analysis of the geometrical modifications effects on the tensile strength of bonded single-lap joints, International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives, 134, 103814, (2024)

Khoramishad, H., Hamzenejad, M. & Ashofteh, R. S. Characterizing cohesive zone model using a mixed-mode direct method. Eng. Fracture Mech. 153, 175–189 (2016).

Yang, K. et al. Mechanical Properties Test and Failure Analysis of Composite Foam Sandwich Structure in Ramp-Down Zone. Mech. Compos. Mater. 60(5), 1–14 (2024).

Dong, J.L., Pull - through Characteristics of Carbon Fiber Braided Composites in Hot and Humid Environ. Harbin Inst. Technol. (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Y. designed the experiments. S.J. conducted the experiments. PY.L. conducted the simulation. Z.L. and P.L. completed the experiment and built the simulation model Z.L. and X.Q.designed specimens size optimization, L.Y. and Z.L. have contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, K., Liu, Z., Qi, X. et al. Failure analysis and size optimization of CFRP composite single-lap bonded joints based on the influence of multiple parameters. Sci Rep 14, 32034 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83605-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83605-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Investigation of flexural mechanical and creep properties of sleeve reinforced pultruded glass fibre reinforced polymer composite for crossarm application

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Effect of fitting tolerance on mechanical performance of CFRP/Al double-lap blind riveted joints

Scientific Reports (2025)