Abstract

To optimize screen quality for a better and healthier visual experience, it is essential to understand how photometric parameters impact ocular physiological parameters. However, the relationship between these photometric and physiological parameters has still not been clearly defined. In this study, time series data of accommodative response and ocular imaging quality at various time points during screen viewing were analyzed, examining different screen photometric parameters. The concept of “tolerance duration” based on these time series curves was introduced. The findings indicate that accommodative response is sensitive to screen brightness, while ocular imaging quality is affected by spectral power distribution. The mathematic models of time-dependent dynamics for both accommodative response and ocular imaging quality were developed, consisting of positive and negative forces. The accommodative response displayed an exponential decay and linear increase pattern, whereas the ocular imaging quality corresponded more closely to sigmoid functions. This innovative model could broaden the understanding of ocular physiological changes during screen use. Additionally, it may offer useful insights for optimizing screen photometric parameters and assist in monitoring ocular responses in clinical research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid advancement of display technology has significantly transformed lifestyles. As the use of display devices (such as computers, smartphones, and tablets) is generally associated with prolonged periods of near vision, concerns about visual health have increased1,2,3.

Several studies have explored the relationship between visual symptoms and spent using displays, concluding that extended use can lead to increased ocular discomfort and visual symptoms4,5,6. However, attributing these discomforts or symptoms solely to display use without considering potential visual dysfunctions—such as refractive, accommodative, or binocular issues—may be misguided7,8,9. Recent research suggests that visual symptoms are primarily dependent on the presence of any sort of visual dysfunction (such as refractive, accommodative, and binocular dysfunction) rather than the prolonged use of digital device10.

Researchers in the area of displays strive for enhanced user experience by regulating the photometric parameters such as screen brightness11, color-gamut coverage12,13,14, color deviation15,16, and spectral power distribution (SPD)16. Higher screen quality is typically associated with greater color-gamut coverage and reduced color deviation17, while the impacts of screen brightness18,19,20 and SPD2,21 on screen quality presents more complexity. The challenge in optimizing screen quality often stems from the lack of clear guidelines on appropriate levels of screen brightness and SPD.

Prior to addressing the optimal screen brightness and SPD, it is crucial to understand accommodative response and ocular imaging quality under varying levels of these parameters. In the current study, time series data of accommodative response and ocular imaging quality were measured and simulated across different levels of screen brightness and SPD. Additionally, the time-dependent dynamics of these ocular responses during screen viewing were explored.

Materials and methods

Light environment

In the experiments conducted for this study, the light environment consisted of varying brightness conditions and varying SPD conditions.

In the varying brightness environments, the ambient illuminance was set at 500 lx, as this illuminance level was extensively used for indoor lighting22. The correlated color temperature (CCT) was set to be 4500 ± 250 K, as this range was considered to be beneficial for visual experience23. The screen, which was labeled as LA, was tested at brightness levels of 130, 200, and 270 cd/m2, as these three screen brightness levels were common brightness settings in display devices24.

In the varying SPD environments, both the ambient illuminance and CCT was maintained at 500 lx and 4500 ± 250 K, respectively, with the screen set at 200 cd/m2 Experiments were performed using screen LA, as well as two additional screens (denoted as LB and LC). Overall, there were three different screen brightness levels in the varying brightness environments, and three distinct SPDs in the varying SPD environments.

Table 1 summarizes the photometric parameters of these light environments, and Fig. 1 illustrates the SPDs of LA, LB, and LC. A total of 15 screens were prepared for the experiments. For both the varying brightness and SPD environments, the screens were divided into three groups, each corresponding to one of the light environments, with each group containing five screens with identical photometric parameters.

Participants and visual tasks

Twenty adults participated in the human factor experiments, detailed in (Table 2). All participants provided written informed consent, and all methods and experimental protocols were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Participants completed display visual tasks in each light environment. Each visual task included a Landolt-ring counting task (occupying 40% of the total task duration) and a color-recognition task (occupying 60% of the total task duration). In the Landolt-ring counting task, the screen displayed Landolt rings in multiple lines, with the gap direction of each ring randomized. Participants were instructed to mark the rings according to the specified direction. In the color-recognition task, colored boxes appeared on the screen in random arrangements, and participants were guided to mark the boxes of a specified color.

Ocular physiological parameters

Accommodative responses and ocular imaging quality were assessed using a NIDEK AR-1 S Refractometer and NIDEK Refractive Power / Corneal Analyzer OPD-Scan lll, respectively. For each measurement of accommodative response, data were collected over a 30 s period. Participant focused on a moving stimulus within the device, and their accommodative response varied with the stimulus. The instrument recorded 30 measurements, denoted as Ri (i = 1, 2, …, 30), representing accommodative responses. As shown in Fig. 2A, the difference between R1 and R30 was denoted as ACC, with the quantitative description explained in the following equation:

The area SR between the Ri curve and the time (abscissa) axis described accommodative responses

Suppose the visual task lasted for time t (0 < t < 45) during the collection of Ri, therefore SR(t) could be treated as a function of t. By subtracting SR(t) from SR(0), the value of ∆SR(t) (which is employed to indicate the time dependency of accommodative response) could be obtained.

To assess ocular imaging quality, contrast value (denoted as C) at different spatial frequencies were collected. As shown in Fig. 2B, SC represented the area between the contrast curve and the abscissa axis (the spatial frequency axis), while SC+SB indicated the area between the vertical axis and the abscissa axis. This allowed the calculation of the modulation transfer function (MTF) of the human eye using the following equation:

The difference between MTF(t) and MTF(0), denoted as ∆MTF(t), described the time dependency of ocular imaging quality.

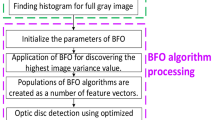

Collection of time series data

To gather the time series data for ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t), experiments were conducted over three days for each light environment. Display visual tasks were scheduled in three intervals: 9:00–11:00, 12:00–14:00, and 15:00–17:00.

Before each task, participants were instructed to relax their eyes by looking into the distance; then, they performed the visual tasks.

Measurements of ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t) occurred before and after the visual tasks. The time series data were recorded at seven key moments: the 0, 5, 10, 15, 25, 35, and the 45th min, as detailed in (Table 3). Explanations of the measured parameters are shown in (Table 4).

Data analysis

For analysis, the average values of ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t) at the 0, 5, 10, 15, 25, 35, and the 45th min were computed for each light environment to generate a time series curve. To compare values at different times and between different light environments, t tests were conducted using SPSS 20.0 software.

Results

Physiological sensitivity to photometric parameters

Before collecting time series data, the 0 and 45th min values of ∆SR and ∆MTF (denoted as ∆SR(45) and ∆MTF(45)) were measured under different light environments characterized by varying brightness and SPDs. The results are shown in Fig. 3A and D; (Table 5). It was found that ∆SR(45) values were similar for screens LA, LB, and LC, but differed significantly across different brightness levels, being higher at 200 cd/m2 but lower at both 130 and 270 cd/m2. Conversely, ∆MTF(45) values remained consistent across brightness levels (130, 200, and 270 cd/m2), but varied noticeably with different SPDs, decreasing progressively from LA to LB to LC. These findings suggest that accommodative response is primarily sensitive to brightness, while ocular imaging quality is more susceptible to SPD.

The accommodative response is associated to zonular control25,26 and the range of vision (depth of focus)27,28, whereas screen brightness is related to light intensity29. The findings indicate that a brightness level of 200 cd/m2 results in less variation in accommodative response compared to 130 cd/m2 and 270 cd/m2, suggesting that 200 cd/m2 may be optimal at an illuminance of 500 lx. Ocular imaging quality is related to contrast sensitivity and resolution30,31, being crucial for detail recognition in human vision. Based on these results, the SPD of LA seems to be more conducive for ocular imaging quality than those of LB and LC. Therefore, both ∆SR(45) and ∆MTF(45) demonstrate sensitivity to brightness and SPD, respectively.

Time series data of ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t)

To further explore the effects of brightness and SPD on the time-dependent dynamics of ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t), the time series data for ∆SR(t) were collected at brightness levels of 130, 200, and 270 cd/m2, and for ∆MTF(t) on screens LA, LB, and LC. The time series curves of ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t) were plotted by connecting the average values at each time point, as shown in Fig. 4A and B. Each curve exhibited an increasing segment followed by a decreasing segment, with the crest (intersection point of the increasing and decreasing segments) occurring between the 5 and the 20th min for ∆SR(t), and between the 0 and the 10th min for ∆MTF(t).

Comparisons of the values between the 0th and the 10th min and between the 10th and the 45th min show that the 10th min values were significantly higher than the 0th min and the 45th min values for both ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t) curves, indicating an “increasing-decreasing” trend, as shown in (Table 6). This trend highlights the regularity of time-dependent dynamics for ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t), where positive and negative values depict response variation directions.

Tolerance duration

The zero values observed in the decreasing segments of the time series curves of ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t) denote moments when the values fall below the 0th-minute levels, indicating such moments as intersection points on the time sequence curve and the time axis. These zero moments, which are defined as the “tolerance durations,” reflect the durations (the positive-value duration) where values remain above the 0th min levels.

Significance tests for tolerance durations between the 0 and the 35th min were performed for ∆SR(t) and △MTF(t), as shown in (able 7). The results indicated that ∆SR(35) values remained significantly above zero at 200 cd/m2, but were marginally below zero at 130 and 270 cd/m2, with all ∆SR(45) values dropping below zero. Consequently, the tolerance duration of ∆SR(t) exceeded 35 min at 200 cd/m2, but was slightly less at 130 and 270 cd/m2. For ∆MTF(t) values across displays, ∆MTF(35) stayed marginally above zero in LA, slightly below zero in LB, and significantly below zero in LC, whereas ∆MTF(45) values fell below zero in both LB and LC. Thus, the tolerance duration for LA approached 45 min, yet remained under 35 min for LB and LC.

The tolerance duration results were in consistent with those of ∆SR(45) and ∆MTF(45), demonstrating that the tolerance duration of the ∆SR(t) is longer at 200 cd/m2 compared to 130 and 270 cd/m2, and the tolerance duration for ∆MTF(t) is longer in LA compared to LB and LC. Consequently, brightness and SPD significantly influence the tolerance durations of ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t), confirming the sensitivity of accommodative response and ocular imaging quality to these photometric parameters.

Quantification model of photometric effects

Although it was possible to compare tolerance durations across different light environments through collected time series data, these were estimates rather than precise calculations. To quantify the effects of photometric parameters on the time-dependent dynamics of accommodative response and ocular imaging quality, dynamic models for ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t) should be constructed and analyzed across different levels of brightness and SPD variations.

The time series curves of ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t) present an increasing-decreasing trend, indicating that dynamics is shaped by positive and negative forces. For ∆SR(t), the functions representing these forces are denoted as A(t) (decaying over time) and F(t) (increasing over time), with their equations shown below:

The parameters A0, λR, and µR are positive constants, with A(t) and F(t) enhancing and reducing ∆SR(t) respectively, rendering the dynamics equation as follows

Where αR and βR are positive constants, and γR is constant. Solving this equation, the expression of ∆SR(t) could be expressed as follows

For ∆MTF(t), the positive and negative force functions are defined as G(t) and D(t) respectively (G and D represents growth and decrease respectively). As growth and decease occurs within limited ranges rather than infinitely changing, the expressions of G(t) and D(t) are shown as follows

The parameters G0, G1, D0, D1, λC, and µC are positive constants. As G(t) and D(t) enhances and reduces ∆MTF(t) respectively, the dynamics equation of ∆MTF(t) would be expressed as follows

Where αC and βC are positive constants, and γC is constant. Solving this equation, the expression of ∆MTF(t) was obtained as follows

The fitted curves showed good agreement with measured values across different light environments, as shown in Fig. 5A–F, with the model parameters detailed in (Table 8). For brightness levels 130, 200, and 270 cd/m2, the predicted tolerance durations of ∆SR(t) were 36, 43, and 38 min respectively; for LA, LB, and LC, the predicted tolerance durations of ∆MTF(t) were 40, 30, and 17 min respectively. These predictions were consistent with the experimental data.

When brightness increased from 200 cd/m2 to 270 cd/m2, parameters A0 and µR in the ∆SR(t) equation rose, while other parameters were not changed, indicating an increase in both positive and negative forces. Conversely, diminishing brightness from 200 cd/m2 led to decreases in these parameters, implying that both positive and negative forces were reduced, yet the corresponding tolerance duration was still shortened. For ∆MTF(t), parameters G0 and D0 decreased as SPD shifted from LA to LB to LC, indicating that the positive force was reduced yet the negative force was kept unchanged.

Moreover, for ∆SR(t) the variations in αRA0 and βRµR as the functions of brightness (denoted as B) with (R2 > 0.99) were fitted as follows

The equations above indicated quadratic brightness effects on positive and negative forces, with axes of symmetry at 125 and 133 cd/m2 for αRA0 and βRµR respectively.

Considering △MTF(t) was susceptible to SPD, the SPD features of LA, LB, and LC were explored. Each SPD was characterized by blue, green, and red crests, with differences in wavelength positions. The blue peak shifted 10 nm toward shorter wavelengths from LA to LB to LC, while red peaks for LB and LC were similar, with LA shifting 10 nm longer. Detailed information of peak positions is shown in (Table 9). From LA to LB, both blue and red peaks shifted toward shorter wavelength; from LB to LC, blue peak position shifted 10 nm to shorter wavelength, yet red peak position shifted 5 nm toward longer wavelength.

To analyze the relationship between blue and red peak positions (denoted as PB and PR respectively) and the model parameters of ∆MTF(t), the equations were built as follows

Where EB1, EB2, ER1, ER2 are fitting parameters. According to Tables 8 and 9, the equations were established as follows

Discussion

This study investigated the association between screen brightness and accommodative responses, and between SPD and ocular imaging quality. The findings suggest that accommodative response is sensitive to screen brightness, making it a potential indicator for determining appropriate screen brightness levels for users. This insight can guide researchers and developers in optimizing screen quality through the regulation of photometric parameters.

Screen brightness is defined as the luminous flux per unit solid angle emitted from a unit area perpendicular to the light ray direction, while illuminance measures the luminous flux received by a unit area29. The results indicate that a screen brightness of 200 cd/m2 is more suitable than either 130 and 270 cd/m2 at an illuminance of 500 lx. This suggests a possible optimal match between this brightness level and the specified illuminance, reflecting the effect of screen-background contrast on user experience during screen use19,20. If illuminance changes, the corresponding appropriate screen brightness level would also need adjustment20,24.

Unlike screen brightness, SPD is more complex as it accounts for spectral irradiance across visible wavelengths29. For simplicity, this study characterized SPD by the peak positions of blue, green, and red spectral crests. The focus was primarily on blue and red crests due to their significant photobiological effects2. The findings suggest that longer wavelengths within these crests are more favorable. Prior research indicates that high doses of short-wavelength blue light may harm retinal health32, while the wavelength around 460 nm can significantly impact melatonin secretion33. Conversely, red light, with its longer wavelengths, is noted for thermal effects and higher penetrability34. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether the beneficial effects of longer wavelengths are associated to melatonin secretion, thermal effects, penetrability, or a combination.

Through experimental data and fitting, the current study quantitatively described the time-dependent dynamics of accommodative responses and ocular imaging quality. The observed “increasing-decreasing” trend is attributed to the interaction of positive and negative forces. For accommodative response, denoted as ∆SR(t), the positive force shows an exponential decay, whereas the negative force increases linearly. These dynamics imply that the negative force will eventually exceed the positive force during screen use, although adjusting screen brightness can influence when this surpassing occurs. In contrast, the dynamics of ocular imaging quality, described by △MTF(t), involve both the positive and negative forces represented by sigmoid functions, with the trend largely dependent on parameters within the model. While both ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t) exhibit “increasing-decreasing” trends, the differing functions of their forces suggest distinct underlying mechanisms.

Clinically, this study provides a novel approach for tracking accommodative response and ocular imaging quality in patients. Clinical researchers can investigate the relationship between ocular responses and eye conditions and apply these time-dependent dynamics to diagnostic processes.

Limitations

There were several limitations in this study:

Visual anomalies

This study did not assess the potential presence of refractive, accommodative, or binocular anomalies among participants. Such underlying visual dysfunctions can lead to visual symptoms such as fatigue, potentially influencing the time-dependent dynamics of accommodative response and ocular imaging quality.

Data collection timing

Data for characterizing the time-dependent regularities of ∆SR(t) and ∆MTF(t) were collected at different intervals (0, 5, 10, 15, 25, 35, and the 45th min) but not within the same experimental session. This staggered approach might have affected the accuracy of the results, as conditions may vary slightly between separate measurements.

Mathematical modeling

The mathematic models describing time-dependent dynamics were developed through fitting based on the experimental data. These data might be potentially explained by multiple equations, indicating that there could be more than one plausible model rather than a unique definitive one.

Age-related factors

Age significantly influences accommodative response35,36 and contrast sensitivity37,38. This study exclusively involved young adult participants to minimize variability due to potential eye diseases common in older populations. Consequently, the findings may not generalize to older individuals who might exhibit different visual dynamics due to age-related changes in vision.

Future studies could address these limitations by including a more comprehensive assessment of participants’ visual health, conducting simultaneous data collection sessions, exploring multiple modeling approaches, and including a broader demographic range, particularly older adults, to enhance the applicability of the results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study elucidated the association between display photometric parameters and ocular physiological parameters. The results demonstrated that screen brightness primarily influences the accommodative response, while SPD affects ocular imaging quality. More specifically, a screen brightness of approximately 200 cd/m2 was determined to be optimal at an illuminance level of 500 lx. Additionally, longer wavelengths in the blue and red spectral segments appeared to benefit ocular imaging quality.

The study identified characteristic “increasing-decreasing” trends in the time-dependent dynamics of both accommodative response and ocular imaging quality. These trends were observable through time series curves, which also allowed for the calculation of tolerance durations—representing the periods during which visual performance remains above a baseline level. The fitted mathematical models revealed that the time-dependent dynamics of accommodative response are impacted by an exponentially decaying positive force and a linearly increasing negative force. In contrast, the dynamics of ocular imaging quality are influenced by sigmoid-shaped positive and negative forces.

Furthermore, an analysis of the model parameters suggested that the dynamics of accommodative response were represented as quadratic functions of screen brightness levels, while the dynamics of ocular imaging quality were influenced by linear functions of the peak positions in the blue and red spectral crests. These insights provide a valuable foundation for optimizing display settings to benefit ocular physiology, potentially enhancing visual experience.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kim, S. et al. Dynamic assessment of visual fatigue during video watching: validation of dynamic rating based on post-task ratings and video features. Displays 85, 102861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.displa.2024.102861 (2024).

Shi, Y. et al. Spectral influence of the normal LCD, blue-shifted LCD, and OLED smartphone displays on visual fatigue: a comparative study. Displays 69, 102066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.displa.2021.102066 (2021).

Jaiswal, S. et al. Ocular and visual discomfort associated with smartphones, tablets and computers: what we do and do not know. Clin. Exp. Optom. 102, 463477 https://doi.org/10.1111/cxo.12851 (2019).

Alabdulkader, B. Effect of digital device use during COVID-19 on digital eye strain. Clin. Exp. Optom. 104, 698704 https://doi.org/10.1080/08164622.2021 (2021).

Ganne, P. et al. Digital eye strain epidemic amid COVID-19 pandemic - a cross-sectional survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 28, 285292. https://doi.org/10.1080/09286586.2020.1862243 (2021).

Usgaonkar, U. et al. Impact of the use of digital devices on eyes during the lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 69, 19011906. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_3500_20 (2021).

Cacho-Martínez, P. et al. Validation of the Symptom Questionnaire for visual dysfunctions (SQVD): a questionnaire to evaluate symptoms of any type of visual dysfunctions. Transl Vis. Sci. Technol. 11, 7. https://doi.org/10.1167/tvst.11.2.7 (2022).

Canto-Cerdan, M. et al. Rasch analysis for development and reduction of symptom Questionnaire for visual dysfunctions (SQVD). Sci. Rep. 11, 14855. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94166-9 (2021).

Canto-Cerdan, M. et al. Delphi methodology for symptomatology associated with visual dysfunctions. Sci. Rep. 10, 19403. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76403-9 (2020).

Cacho-Martínez, P. et al. Assessing the role of visual dysfunctions in the association between visual symptomatology and the use of digital devices. J. Optom. 17, 100510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optom.2023.100510 (2024).

Xu, W. et al. Evaluation and application strategy of low blue light mode of desktop display based on brightness characteristics. Displays 84, 102809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.displa.2024.102809 (2024).

Li, T. et al. Color gamut extension algorithm for various images based on laser display. Opt. Express. 32 (3), 3891–3911. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.507868 (2024).

Patrick, C. et al. Color gamut volume and the maximum number of mutually discernible colors based on a riemannian metric. Opt. Express 31 (19), 31124–31141. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.499593 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. Estimation of the perceptual color gamut on displays. Opt. Express 30 (24), 43872–43887. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.472808 (2022).

Lee, M. et al. A non-contact colour correction system on mobile display under various light sources. Displays 83, 102747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.displa.2024.102747 (2024).

Wang, T. et al. Spectral missing color correction based on an adaptive parameter fitting model. Opt. Express 31 (5), 8561–8574. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.480916 (2023).

Cai, J. et al. Fundus-vascular responses to color deviation caused by non-oxidative blue filtering. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 1, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9592009 (2022).

Yu, H. et al. Effects of illuminance and color temperature of a general lighting system on psychophysiology while performing paper and computer tasks. Build. Environ. 228, 109796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109796 (2023).

Yu, H. et al. Influence of ambient-tablet PC luminance ratio on legibility and visual fatigue during long-term reading in low lighting environment. Displays 62, 101943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.displa.2020.101943 (2020).

Yu, H. et al. Effect of character contrast ratio of tablet PC and ambient device luminance ratio on readability in low ambient illuminance. Displays 52, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.displa.2018.03.002 (2018).

Oh, J. H. et al. Analysis of circadian properties and healthy levels of blue light from smartphones at night. Sci. Rep. 5, 11325. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11325 (2015).

Cai, J. et al. A better photometric index of photo-biological effect on visual function of human eye: illuminance or luminance? IEEE Access 7, 165919–165927. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2953552 (2019).

Cai, J. et al. Influence of LED correlated Color temperature on ocular physiological function and subjective perception of discomfort. IEEE Access 6, 25209–25213. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2780276 (2018).

Zeng, S. et al. Appropriate screen brightness for ambient lighting illuminance. 18th China international forum on solid state lighting & 2021 7th international forum on wide bandgap semiconductors (SSLChina: IFWS), 162–164. https://doi.org/10.1109/SSLChinaIFWS54608.2021.9675263 (2021).

Schachar, R. A. et al. Model of zonular forces on the lens capsule during accommodation. Sci. Rep. 14, 5896. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56563-8 (2024).

Schachar, R. A. et al. Finite element analysis of zonular forces. Exp. Eye Res. 237, 109709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2023.109709 (2023).

Cho, J. et al. Visual outcomes and optical quality of accommodative, multifocal, extended depth-of-focus, and monofocal intraocular lenses in presbyopia-correcting cataract surgery: a systematic review and bayesian network meta-analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 140 (11), 1045–1053. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.3667 (2022).

Wang, B. et al. Depth-of-focus of the human eye: theory and clinical implications. Surv. Ophthalmol. 51 (1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.11.003 (2006).

Kruisselbrink, T. et al. Photometric measurements of lighting quality: an overview. Build. Environ. 138, 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.04.028 (2018).

Lu, Z. et al. Quantifying the functional relationship between visual acuity and contrast sensitivity function. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 65, 33. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.65.12.33 (2024).

Anders, P. et al. Evaluating contrast sensitivity in early and intermediate age-related macular degeneration with the quick contrast sensitivity function. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 64, 7. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.64.14.7 (2024).

Jaadane, I. et al. Retinal phototoxicity and the evaluation of the blue light hazard of a new solid-state lighting technology. Sci. Rep. 10, 6733. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63442-5 (2020).

Figueiro, M. G. et al. Non-visual effects of light: how to use light to promote circadian entrainment and elicit alertness. Light. Res. Technol. 50, 38–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477153517721598 (2018).

Lee, G. H. et al. Multifunctional materials for implantable and wearable photonic healthcare devices. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-019-0167-3 (2020).

Zapata-Díaz, J. F. et al. Accommodation and age-dependent eye model based on in vivo measurements. J. Optom. 12 (1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optom.2018.01.003 (2019).

Kasthurirangan, S. et al. Age related changes in accommodative dynamics in humans. Vis. Res. 46 (8–9), 1507–1519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2005.11.012 (2006).

Zhuang, X. et al. Aging effects on contrast sensitivity in visual pathways: a pilot study on flicker adaptation. PLoS One 16 (12), e0261927. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261927 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Effect of age and refractive error on quick contrast sensitivity function in Chinese adults: a pilot study. Eye 35, 966–972 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-1009-7 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the National Key Research and Development Program (Grant 2023YFF0613001), the Presidential Foundation of China National Institute of Standardization (Grant 512024Y-11446).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C. conceived the project. S.Z., Y.G. and W.H. performed the experimental work. Data analysis and writing of the manuscript were performed by S.Z., Y.G. and W.H. under the supervision of J.C. All authors discussed the results and gave feedback on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, J., Zeng, S., Guo, Y. et al. Analyzing display photometric features through time-dependent dynamics of accommodative responses and ocular imaging quality. Sci Rep 15, 10299 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83771-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83771-z