Abstract

This study investigates the effectiveness of high-throughput phenotyping (HTP) using RGB images from unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to assess vegetation indices (VIs) in different soybean pure lines. The VIs were accessed at various stages of crop development and correlated with agronomic performance traits. The field research was conducted in the experimental area of the Mato Grosso do Sul Foundation, Brazil, with 60 soybean pure lines. RGB images were captured at multiple stages of development (28, 37, 49, 70, 86, 105, 115, and 120 days after sowing). We used a linear mixed effects model, with restricted maximum likelihood (REML)/best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP) methods, to estimate variance components and genetic correlations, and to predict genotypic values. Significant genetic differences were identified among genotypes for all agronomic traits evaluated (p< 0.001), with high accuracy and heritability for plant height, maturity at R8, and 100-seed weight. There was a significant genotype \(\times\) flight data interaction impact on VI expression, emphasizing the importance of timing data collection to enhance HTP with VIs in agronomic performance evaluation. In the early stages, the indices varied depending on the environment. On the other hand, the indices showed higher correlations with the traits of plant height and maturity at the R8 stage, at 105, 115, and 120 days after sowing. HTP with VIs based on RGB images from UAVs has proven to be more effective in the early and final stages of soybean development, providing essential information for the selection of superior genotypes. This study highlights the importance of the temporal approach in HTP, optimizing the selection of soybean genotypes and refining agricultural management strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merril] is one of the most important crops globally, and Brazil is its largest producer1. This market dominance is a direct result of advances in genetic improvement that have increased the productive efficiency of cultivated varieties2,3. In turn, high-throughput phenotyping (HTP) in soybean cultivation is complex due to genetic diversity and varied plant responses to different environmental conditions4. This raises associated costs, limiting the efficiency and precision of genetic analyses. In this regard, HTP enables rapid and detailed analysis of physical and biological plant characteristics, contributing to more precise and efficient breeding strategies5,6.

The combination of optical sensors coupled with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and robust data analysis is driving the field of HTP7,8. The integration of these tools enables the collection of data on a large scale and with high precision, allowing for the rapid identification of vital plant characteristics such as health, growth, and response to environmental stresses. This approach has been applied in various crops, with digital cameras standing out due to their wide applicability and ease of integration with plant phenotyping platforms6,8. Digital cameras capture images using the three primary color channels - red, green, and blue (RGB), allowing for detailed analysis of plant visual characteristics9.

Vegetation indices (VIs) are quantitative parameters derived from the combination and analysis of RGB color channel intensities reflected by plants, such as RGVB - Red green blue vegetation index, GLI - Green Leaf index, and NGR - Normalized green-red vegetation index10,11. These indices provide information about plant health and vigor, as well as serving as sensitive indicators of characteristics such as biomass, water stress, and photosynthetic efficiency12. In the context of genetic improvement, the use of these indices allows for a non-invasive and large-scale assessment of crop phenotypic characteristics. This enables the rapid identification of superior lines and the selection of desirable traits with greater precision and efficiency4,11.

Temporal analysis of VIs can reveal patterns of plant growth and development, allowing researchers to better understand genotypic responses to different environmental conditions9,13. In turn, mixed models allow for more precise analysis of genotypic effects and genotype \(\times\) stages of crop development, crucial in the context of genetic, climatic, and management variations. Mixed models offer a more suitable robust structure for decomposing variability because they consider both fixed and random effects. The application of mixed models using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method in estimating BLUPs (Best Linear Unbiased Predictors) is particularly valuable for isolating genetic effects, allowing for more accurate correlations between VIs and agronomic traits14. Evaluating a target population of genotypes using multi-environment trials allows for the measuring of genotype-by-environment (G \(\times\) E) interaction. When explored, this interaction reveals the adaptability of genotypes. In cases of crossover interaction, it can alter the performance of selection candidates15. Additionally, assessing genotype \(\times\) flight date interaction is essential for reliable selection, especially when combined with HTP. Therefore, the aims of this study were: to evaluate the effectiveness of VIs in phenotyping pure soybean lines using RGB images captured by a UAV at different developmental stages of the crop; to correlate these VIs with agronomic performance traits.

Methods

Plant material

The soybean dataset comprises four conventional soybean pure lines, nine Roundup Ready technology cultivars, and forty-seven genotypes of INTACTA RR2 PRO technology (Supplementary Table 1). The maturity groups of the genotypes ranged between 6.0 and 7.5. Data were collected throughout the 2020/2021 growing season. The study was conducted in the soybean breeding experimental area at the Mato Grosso do Sul Foundation Research Unit on Alegria Farm (latitude 21° 38’ S, longitude 55° 06’ W, and altitude 360 m) in Maracaju, a city in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil.

Experimental design and growing conditions

Pure lines were evaluated in three experimental areas, located contiguously in the same Research Unit. Each area was implemented at different dates. We incorporated the sowing date as an environmental variation effect, facilitating a joint analysis of trials across different planting times. Henceforth, we will call this effect an “environment” (sowing dates - SD1, SD2, and SD3). The trials had a complete randomized block design with three replications. Soybean sowing was done using direct seeding with a vacuum seed distribution system, in plots of 5 rows of 12 m, with 0.5 m between rows, and an area of 30 m². The useful plot area was formed by the three central rows of 11 m, discarding 0.5 m at both ends.

The seeds were treated with Standak Top at a dose of 2 ml kg-1 and with liquid inoculant via the stalk - Bradyrhizobium + Azospirillum (1 dose - providing at least 1.2 million cells per seed, according to the manufacturer). Maintenance fertilization was performed with 330 kg ha-1 of NPK (02-20-20). The soil cover was maintained with corn and Brachiaria straw. Foliar fertilization was performed at stages V4, R1, R3, and R4/R5, as detailed in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table 2). Fungal control was carried out in four applications, with the following fungicides: 1st application - propiconazole + difenoconazole (0.15 L ha-1 a.i.); 2nd application - trifloxystrobin + prothioconazole (0.4 L ha-1 a.i.); 3rd application - epoxiconazole + fluxapyroxad + pyraclostrobin (0.80 L ha-1 a.i.); and, 4th application - trifloxystrobin + ciproconazole (0.2 L ha-1 a.i.) + mancozeb (1.5 kg a.i.). Weed and pest control were carried out following recommendations for the region.

Agronomic traits

The evaluations were carried out in the physiological maturity stage (R8), when there is a maximum accumulation of dry matter in the grains (fully mature grains). Lodging (LDG) was assessed using a rating scale of 1 to 5, where 1—indicates all plants erect, 2—up to 25% of plants lodged, 3—26 to 50% of plants lodged, 4—51 to 80% of plants lodged, and 5—above 81% of plants lodged. Plants were considered lodged when they had an inclination angle of 45° or higher. Plant height (PH) was measured from the soil surface to the apical end of the main stem, using a tape measure, at three randomly selected points in the plot, and the results were expressed in cm. Maturity at R8 was assessed as the number of days from emergence to stage R8, which corresponds to full soybean maturation, expressed in days. Hundred-seed weight (100-SW) was evaluated by direct weighing on a precision balance. The seed yield (SY) was determined by weighing the harvested useful area (15 m2 of each plot) and then converted to kilograms per hectare, standardized to a moisture content of 13%.

High-throughput phenotyping analysis

The canopy development of soybean pure lines was monitored using digital images obtained from overflights, using a Drone (DJI Phantom 4) equipped with its own camera (RGB) with 20 megapixels. At the beginning of sowing, plots and ground control points (GCPs) were marked in the form of an X (white) placed throughout the study area. The coordinates of each control point were obtained by GNSS-RTK receiver (Global Navigation Satellite System-Real Time Kinematic) and were used to generate the orthomosaic from the images captured by the ARP at each sowing time (Fig. 1).

The flights were autonomously conducted with a plan created in the Dronedeploy® application and began from seedling emergence until harvest, 28, 37, 49, 70, 86, 105, 115, and 120 days after sowing (DAS). One flight per day was conducted, lasting between 15 and 25 minutes, at an altitude of 50 m and a speed of 3 m/s, with a 1 cm pixel size for greater image precision. The images were captured with a lateral overlap of 80% and a frontal overlap of 75% for the construction of the final orthomosaic. UAV flights were conducted under stable environmental conditions on calm, clear days within specific flight windows to ensure data consistency. A single flight capturing multiple images per phenotyping session was performed to enhance image quality and overlap. The weather parameters (temperature, humidity, and wind speed) were continuously recorded throughout the growing season.

Image processing was performed using Agisoft MetaShape software (version 1.5.3, Agisoft LLC, St. Petersburg, Russia), where orthomosaics for each date were generated to obtain vegetation indices. The extraction of spectral variable values was performed using Quantum GIS v.3.10.14 software (QGIS Development Team, Open Source Geospatial Foundation). Colorimetric indices based on the RGB wavelength spectrum were considered. The aerial images captured were analyzed using the R program, utilizing functions from the FieldImageR package12 to estimate the vegetation indices detailed in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

All statistical procedures are based on the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) test16 for estimating variance components; and on the best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP) method for predicting genotypic values17. We used two different models for traits and indices. For trait, the following multi-environment model was fitted:

where \({\textbf {y }}\) is the vector of phenotypic observations; \({\textbf {b}}\) is the vector of fixed effects (intercept, environment and repetitions); \({\textbf {g}}\) is the random effect of genotype nested within environments, modelled using a compound symmetry correlation structure (\(\textbf{g} \sim N( \textbf{0}, \sigma ^2_g \varvec{\Phi } \otimes \textbf{I}_V\), where \(\varvec{\Phi }\) is a matrix with ones in the diagonal and a uniform correlation \(\rho\) in the off-diagonals, and V is the number of genotypes). and \(\varepsilon\) is the vector of residual effects, modelled using a block-diagonal structure (\(\varvec{\varepsilon } \sim N(0, \oplus _p^M \sigma _{\varepsilon _p}^{2} \textbf{I}_N)\), where M is the number of environments [\(p = 1, 2, \dots , M\)], N is the number of plots per environment, and \(\oplus\) is the direct sum symbol).

Following, we fitted a multi-environment repeated measures model for the indices’ data:

where \({\textbf {y}}\) is the vector of phenotypic observations, \({\textbf {b}}\) is the vector of fixed effects (intercept, environment, flight date nested within environment, and repetitions nested within date and environment), \({\textbf {g}}\) is the random main effects of genotypes (\({\textbf {g}} \sim N(0,\sigma _g^2 {\textbf {I}})\)), \({\textbf {ge}}\) is the vector of genotype \(\times\) environment interaction effect (\({\textbf {gd}} \sim N(0,\sigma _{ge}^2 {\textbf {I}})\)), \({\textbf {gd(e)}}\) is the vector of genotype \(\times\) flight date interaction, nested within environments (\({\textbf {gd}} \sim N(0,\sigma _{gd(e)}^2 {\textbf {I}})\)), and \(\varvec{\varepsilon }\) is the vector of residual effects, modelled using a block-diagonal structure between environments, and a heterogeneous first-order autoregressive structure between flight dates. From this model, the BLUPs were obtained within each flight date (i.e., \({\textbf {g}} + {\textbf {ge}} + {\textbf {gd(e)}}\)).

With the BLUPs of traits and indices, we computed the correlation between them, within environments and flight dates (different days after sowing). We also performed the likelihood ratio test (LRT) to detect the significance of the genotypic variation. The LRT statistic was estimated as follows:

where L\(_{r}\) is the maximum point of the likelihood function of the reduced model, and L\(_{c}\) is the maximum point of the likelihood function of the complete model. The result of this equation was compared with values from the chi-square distribution, with degrees of freedom equal to 1.

Finally, we estimated the heritabilities at the plot level were estimated as follows:

where D and B are the number of flight dates and blocks, respectively.

Ethical statement

The plant species used here is a cultivated plant (G. max L.), and the genotypes employed were provided by the Mato Grosso do Sul Foundation (Fundação MS), located in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. We confirm that we have complied with all the necessary regulations for this type of research.

Results

The results revealed significant differences (p < 0.001) by the LRT test for all evaluated agronomic traits, as indicated in Table 2. The boxplots display the distribution of traits in soybean genotypes, including R8, PH, LDG, 100-SW, and SY. R8 and PH show medians of 110 and 130, respectively, with greater variability in height. In contrast, 100-SW and SY have medians of 16.5 and 4300, respectively, with low variability, indicating higher consistency. These results suggest that 100-SW and SY are reliable for selection, while the variability in PH and LDG should be monitored to improve plant uniformity (Fig. 2).

The genetic variance was notably higher for SY and PH, with values of 51,800 and 131.36, respectively (Table 3). Genetic accuracy estimates exceeded 0.9 for R8 and PH across all three trials, indicating strong reliability for selection based on these traits. Additionally, high experimental precision was observed across the experiments, with values ranging from 0.008 (R8-SD1) to 0.39 (LDG-SD1). These findings highlight the importance of these parameters for these traits, providing a solid foundation for effective breeding strategies.

All vegetation indices showed significant differences for the genotype effect, as indicated by the LRT test (p < 0.001), revealing genetic variability (Table 4). The genotype \(\times\) environment (G\(\times\)E) interaction was not significant; however, there was a significant statistical difference (p < 0.001) for the genotype \(\times\) flight data (G\(\times\)GD) interaction, indicating that genotypes exhibited distinct behaviors across different flight periods.

The genetic variance component ranged from 0.000149 (BGI) to 17.1 (RED), with indices like E\(\times\)G, E\(\times\)B, RED, GREEN, and BLUE showing higher values (Table 5). These indices also exhibited significant G\(\times\)GD interaction, indicating that their responses vary significantly between flight datas, further emphasizing their environmental sensitivity and potential for selective breeding or environmental adaptation studies.

The Table 6 presents the correlations (\(\rho\)) across different environments (SD1, SD2, and SD3) for various vegetation indices, indicating the degree of association between index measurements in each environment and reflecting each index stability or sensitivity to environmental variations. For instance, the BGI index shows a positive correlation in SD1 (0.313) but a strong negative correlation in SD2 (\(-6.96\)), suggesting that this index’s responses are highly influenced by the specific conditions of SD2. In contrast, correlations close to zero, such as the BLUE index in SD2 (0.0011), indicate minimal association in that particular environment. These results indicate that the interaction between genotypes and flight data in a multi-environment context highlights which indices are more stable across environments and which respond differently. This provides valuable insights into the robustness of each vegetation index under varying environmental conditions.

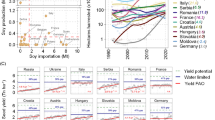

Heritability ranged from 0.5 (SD1 - SY) to 0.9 (SD1 - R8), indicating that the phenotype reflects the genotype well (Fig. 3a). For vegetation indices, heritability varied according to the environment and flight data. At 49 DAS, heritability showed low values, unlike at 105 DAS, where higher values were observed (Fig. 3b). The correlation between vegetation indices varied depending on the date of sowing in the different trials. In environment SD1, at 37, 105, 115, and 120 DAS, high correlations were observed, ranging from negative to positive for PH and R8. In environment SD2, at 28 DAS, these traits also showed higher correlations, as well as at 115 days. In environment SD3, at 115 and 120 days, the strongest correlations with the vegetation indices were recorded (Fig. 4).

Discussion

All agronomic traits studied in soybeans showed genetic variability. Additionally, the indices E\(\times\)G, E\(\times\)B, RED, GREEN, and BLUE, also showed strong genetic influence and differentiated temporal influence on the studied genotypes. These results are aligned with previous studies highlighting a wide genetic diversity underlying complex agronomic traits in soybeans18. Genetic diversity in soybean germplasm from different geographical regions, such as China, Brazil, and Japan, and in wild soybean populations, has been well documented18,19,20,21. Particularly in Brazil, the genetic diversity of soybeans may be associated in part with plant adaptation to Brazilian environments20. Most of the important agronomic traits result from various genetic, molecular, and physiological mechanisms that affect the trait of interest, directly or indirectly through other intermediate traits22. Therefore, the results on the genetic influence and The interaction between flight date and VI reinforces the importance of understanding genetic expression for genetic improvement.

The variation in VI across different flight dates (physiological stages) in soybean crops can be explained by the physiological and morphological changes that plants undergo throughout their development. As soybeans grow and develop, changes occur in leaf structure, chemical composition, and interaction with the environment, affecting how leaves reflect light and, consequently, causing changes in VI7,23. For example, in the early stages, lower leaf density may result in different light reflection patterns, impacting indices such as E\(\times\)G and GLI, which are sensitive to the green color6. As the plant develops and leaf density increases, changes in light absorption and reflection can be captured by indices such as Red and Green. Therefore, variations during plant physiological maturity can influence VI such as NGR and RGVB, which are indicative of vegetative vigor and maturity9,24.

Heritability and accuracy are fundamental parameters in quantitative genetics and genetic improvement. While heritability indicates the proportion of the phenotypic variance of a trait attributable to genetic variance25, accuracy reflects the precision with which true genetic values are estimated11. Therefore, high heritability coupled with high accuracy suggests potential for success in genetic selection and improvement of specific traits in a population.

In this research, the agronomic traits that showed higher heritability and accuracy were PH, R8, and 100-SW. Previous studies have also highlighted the importance of these traits in the context of soybean breeding, emphasizing their relevance to cultivar productivity and adaptability25,26. In turn, the vegetation indices (VI) with higher heritability were RED, GREEN, and GLI. Together, these results allow us to conclude that these traits are promising for genetic breeding programs in soybeans. The high accuracy of these traits enables the selection of genotypes with superior performance, contributing to the development of soybean varieties with higher productivity and quality. Therefore, focusing on improving these specific indices can lead to the development of lines with desirable phenotypic characteristics.

The correlation analysis between vegetation indices and agronomic traits, such as R8, SY and 100-SW, has provided valuable information on genetic and environmental influence on the expression of these traits4. In this work, PH and R8 were the agronomic traits most strongly correlated with the VI. PH is a key indicator of vegetative vigor and potential yield26. In turn, R8 maturity, which corresponds to the number of days from emergence to full plant maturity, influences plant phenology, harvest yield, and seed quality, becoming a fundamental characteristic for optimizing productivity in genetic breeding programs12. Thus, the correlations of these traits with the VI indicate that the indices are non-destructive, rapid, and efficient tools for monitoring the development of soybean varieties, allowing for more precise agronomic interventions and the enhancement of selection and genetic breeding strategies. The application of VI in HTP of soybeans has been widely explored, with studies using regression models to predict the relative maturity of soybean lines based on VI derived from UAV images4,6,12. In addition to the correlations with PH and R8 recorded in this work, correlation models between plant morphological characteristics and VI have shown potential to assess vegetation cover, nutritional status, vigor, growth, and crop productivity in other studies12.

The highest values of significant correlations between the BLUPs of the VI and the BLUPs of the agronomic traits in the early stages of development can be interpreted as a reflection of the initial growth dynamics of the different soybean varieties, where the spectral colors captured by RGB images change significantly as the plants develop9,23. This pattern changed during the intermediate stages of development, between 49 and 86 DAS, when significant correlations were limited to the RED index. Probably, the plants of all varieties had reached the maximum stand of vegetative development, with few variations in agronomic traits and in VI among varieties and a lower relationship between the traits. In the final stages of plant development, a larger number of VI again showed significant correlations with agronomic traits. This result can be interpreted as a plant response to the maturation phase, where physiological and morphological changes, such as changes in leaf and pod density and coloration, can influence spectral reflection, especially in the RED range captured by RGB images24.

Taken together, the correlation results highlight the relevance of VI, obtained from UAV RGB images, as potential tools for monitoring the development and maturation of soybean cultivars, similar to the results obtained by other authors4,12,25. There is a robust association between plant height and indices that capture green color intensity, possibly reflecting a period of vigorous growth and intense leaf development. The variations in correlations observed throughout the crop cycle suggest that different indices may be more suitable for monitoring different stages of plant development. This understanding can contribute to the improvement of agricultural management strategies and cultivar selection, as well as provide valuable information for future research in the field of HTP.

The findings of this research also suggest that phenological changes associated with soybean maturation are strongly related to the GREEN and RED spectral characteristics of plants, captured in indices such as Red or RGVB, NGR, GLI, and E\(\times\)G. These results indicate a complex interaction between soybean maturation and VI, potentially reflecting leaf senescence dynamics and changes in plant chemical composition that affect light reflection in the spectral bands captured24. However, the results suggest a limited influence of VI in predicting plant lodging and productivity under the studied conditions.

The effect of the interaction G\(\times\)GD, evaluated using mixed linear models, allowed us to understand the temporal variation in VIs at different stages of crop development. This component provides valuable insights into how specific VIs respond to environmental and developmental factors at distinct growth stages. Our findings demonstrate that VIs such as RGVB, NGR, and GLI showed greater efficacy during early vegetative and maturity phases, while other indices, such as RED, exhibited different correlation patterns. Upon reconsidering this analysis, we can better distinguish the ideal stages for UAV-based HTP data collection, ensuring that the selection of superior genotypes is more precise and effective. These results emphasize the importance of adapting UAV flights to specific crop growth periods to maximize the predictive power of VIs for agronomic traits27.

Schematic representation of high-throughput phenotyping study in soybean genotypes. The experimental area with flight plan, orthomosaic generated after sowing, software used for extraction of spectral variable values and some vegetation indices, and the correlation between vegetation indices and agronomic traits are depicted.

Boxplot representation of the distribution of lodging (LDG), plant height (PH), R8 maturation stage (R8), 100-seed weight (100-SW), and seed yield (SY) in soybean genotypes. See the caption of Fig. 2.

Correlation map of the BLUPs of vegetation indices, obtained through mixed models from RGB image data captured using drones, with the BLUPs of agronomic traits in soybean cultivars across all three trials. See the caption of Fig. 2.

Conclusions

The optimal timing for conducting HTP in soybeans, using IVs derived from RGB images captured with UAVs, occurs during the early stages of crop development (at 28 and 37 DAS) or during the late stages of development (from 105 to 120 DAS). These stages of crop development have shown the highest correlations between IVs and agronomic traits. These timings provide a window to capture critical information about plant growth and maturation. However, the effect of the interaction between genotypes and flight data should be evaluated in order to be more reliability in the selection.

The agronomic traits most strongly correlated with IVs are R8 maturity and plant height. The variations in correlations over time emphasize the importance of a temporal approach in the application of IVs for agronomic performance analysis. The selection of specific indices and the plant development stage at the time of data collection are essential to maximize the utility of the collected information for soybean crop management. The results presented here demonstrate the potential of RGB images captured by UAVs as a practical and efficient approach for evaluating phenotypic characteristics on a large scale, providing a solid foundation for future research and practical applications in crop improvement and management.

Data availibility

The dataset used and/or analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service. Soybean production, marketing costs, and export competitiveness in Brazil and the United States. In: TypeTech Report Number EIB-262, Institution U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (2023).

Rahman, S. U. et al. Improvement of soybean; A way forward transition from genetic engineering to new plant breeding technologies. Mol. Biotechnol. 65, 162–180 (2023).

Umburanas, R. C. et al. Changes in soybean cultivars released over the past 50 years in southern Brazil. Sci. Rep. 12, 508 (2022).

Santana, D. et al. High-throughput phenotyping allows the selection of soybean genotypes for earliness and high grain yield. Plant Methods 18, 13 (2022).

Li, D. et al. High-throughput plant phenotyping platform (ht3p) as a novel tool for estimating agronomic traits from the lab to the field. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 623705 (2021).

Yang, G., Liu, J. & Li, Z. Unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing for field-based crop phenotyping: Current status and perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 272832 (2017).

Feng, L., Chen, S., Zhang, C., Zhang, Y. & He, Y. A comprehensive review on recent applications of unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing with various sensors for high-throughput plant phenotyping. Comput. Electron. Agric. 182, 106033 (2021).

Solimani, F. et al. A systematic review of effective hardware and software factors affecting high-throughput plant phenotyping. Information 14, 214 (2023).

Bendig, J. et al. Combining UAV-based plant height from crop surface models, visible, and near infrared vegetation indices for biomass monitoring in barley. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 39, 79–87 (2015).

Fei, S. et al. Assessment of ensemble learning to predict wheat grain yield based on UAV-multispectral reflectance. Remote Sens. 13, 2338 (2021).

Ferreira, F. M. et al. Bioenergy elephant grass genotype selection leveraged by spatial modeling of conventional and high-throughput phenotyping data. J. Clean. Prod. 363, 132286 (2022).

Ren, P. et al. Estimation of soybean yield by combining maturity group information and unmanned aerial vehicle multi-sensor data using machine learning. Remote Sens. 15, 4286 (2023).

Silva, C. M. et al. Insights on multi-spectral vegetation indices derived from UAV-based high-throughput phenotyping for indirect selection in tropical wheat breeding. Euphytica 220, 35 (2024).

Araújo, M. D., Chaves, S. F., Damasceno-Silva, K. J., Dias, L. A. S. & de Rocha, M. D. Modeling covariance structures for genetic and non-genetic effects in cowpea multi-environment trials. Agron. J. 115, 1248–1256 (2023).

Poupon, V., Gezan, S. A., Schueler, S. & Lstiburek, M. Genotype \(\times\) environment interaction and climate sensitivity in growth and wood density of European larch. For. Ecol. Manag. 545, 121259 (2023).

Patterson, H. D. & Thompson, R. Recovery of inter-block information when block sizes are unequal. Biometrika 58, 545–554 (1971).

Henderson, C. R. Best linear unbiased estimation and prediction under a selection model. Biometrics 423–447 (1975).

Fang, C. et al. Genome-wide association studies dissect the genetic networks underlying agronomical traits in soybean. Genome Biol. 18, 1–4 (2017).

Wang, K. J. & Takahata, Y. A preliminary comparative evaluation of genetic diversity between Chinese and Japanese wild soybean (Glycine soja) germplasm pools using SSR markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 54, 157–165 (2007).

Mendonça, H. C., Pereira, L. F., Maldonado dos Santos, J. V., Meda, A. R. & Sant’Ana, G. C. Genetic diversity and selection footprints in the genome of Brazilian soybean cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 842571 (2022).

Kim, W. J. et al. Genome-wide association study for agronomic traits in wild soybean (Glycine soja). Agronomy 13, 739 (2023).

Dhungana, P. et al. Analysis of genotype-by-environment interaction in wheat using a structural equation model and chromosome substitution lines. Crop Sci. 47, 477–484 (2007).

Louhaichi, M., Borman, M. M. & Johnson, D. E. Spatially located platform and aerial photography for documentation of grazing impacts on wheat. Geocarto Int. 16, 65–70 (2001).

Zhou, J., Yungbluth, D., Vong, C. N. & Scaboo, A. Estimation of the maturity date of soybean breeding lines using UAV-based multispectral imagery. Remote Sens. 11, 2075 (2019).

Kuswantoro, H., Adie, M. M. & Putri, P. H. Genetic variability, heritability, and genotypic correlation of soybean agronomic characters. Bull. Palawija 19, 117–125 (2021).

Machado, B. Q. et al. Phenotypic and genotypic correlations between soybean agronomic traits and path analysis. Genet. Mol. Res. 16, 1–1 (2017).

Washburn, J. D., Adak, A., DeSalvio, A. J., Arik, M. A. & Murray, S. C. High temporal resolution unoccupied aerial systems phenotyping provides unique information between flight dates. Plant Phenome J. 7, e20113 (2024).

Woebbecke, D. M., Meyer, G. E., Von Bargen, K. & Mortensen, D. A. Color indices for weed identification under various soil, residue, and lighting conditions. Trans. ASAE 38, 259–269 (1995).

Meyer, G. E. & Neto, J. C. Verification of color vegetation indices for automated crop imaging applications. Comput. Electron. Agric. 63, 282–293 (2008).

Mao, W., Wang, Y. & Wang, Y. Real-time detection of between-row weeds using machine vision. In 2003 ASAE Annual Meeting. Vol. 1 (2003).

Tucker, C. J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 8, 127–150 (1979).

Gitelson, A. A., Kaufman, Y. J., Stark, R. & Rundquist, D. Novel algorithms for remote estimation of vegetation fraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 80, 76–87 (2002).

Hague, T., Tillett, N. D. & Wheeler, H. Automated crop and weed monitoring in widely spaced cereals. Precis. Agric. 7, 21–32 (2006).

Zarco-Tejada, P. J. et al. Assessing vineyard condition with hyperspectral indices: Leaf and canopy reflectance simulation in a row-structured discontinuous canopy. Remote Sens. Environ. 99, 271–287 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Brazilian Federal Agency for Suport and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES), São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), Minas Gerais State Agency for Research and Development (FAPEMIG), Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Mato Grosso do Sul Foundation (Fundação MS), FMS Fundation, and Federal University of Viçosa (UFV). Maurício dos Santos Araújo was supported by FAPESP (São Paulo Research Foundation, Grant 2024/01868).

Funding

This work was supported by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES, Finance Code 001), São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, Grant 2024/01868), Minas Gerais State Agency for Research and Development (FAPEMIG), and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived the experiment(s): [A.K.S.A., M.S.A., S.F.S.C.]; Conducted the experiment(s): [A.R.G.B.]. Provided insights into the methodology: [L.A.S.D., L.P.C.]; Analyzed the results: [A.K.S.A., M.S.A., S.F.S.C.]; Writing - review and editing: (A.K.S.A., M.S.A., S.F.S.C., G.G.F.A.P]; Provided critical revisions of the paper drafts [A.K.S.A., L.A.S.D.]. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alves, A.K.S., Araújo, M.S., Chaves, S.F.S. et al. High throughput phenotyping in soybean breeding using RGB image vegetation indices based on drone. Sci Rep 14, 32055 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83807-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83807-4

This article is cited by

-

A century of research on Azospirillum and still so much to discover

Plant and Soil (2026)