Abstract

Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH) is frequently difficult to diagnose due to the absence of specific symptoms, yet early detection and surgical intervention are essential for preventing sequela such as irreversible dementia. This study explores the specific magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features of the brainstem and mesencephalic aqueduct in patients with iNPH. Head MRI data of 50 iNPH patients and 30 healthy matched controls were compared for mesencephalic aqueduct length, diameter, and angle, structural features of the brainstem at the sagittal plane, brainstem component volume ratios, angle between the brainstem and spinal cord, and the area and morphology of the pontine cisterns. Compared to healthy individuals, iNPH patients exhibited significant dilation of the mesencephalic aqueduct diameter, a reduced aqueduct angle, and a decrease in the sagittal plane area of the brainstem, with the most pronounced reduction in the midbrain region. Notably, the CSF spaces surrounding the brainstem were dilated, resulting in the prepontine cistern presenting a “hammer-like” shape on the sagittal plane. The prevalence of this hammer shape was positively correlated with prepontine cistern area in patients with iNPH. These unique imaging characteristics may facilitate the clinical recognition of iNPH for early diagnosis and treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is a form of communicating hydrocephalus in which the ventricles are enlarged but the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure is within the normal range (70–200 mmH2O)1. According to etiology, NPH can be classified as secondary (sNPH) or idiopathic (iNPH). While both forms lack highly specific neurological symptoms, those of sNPH appear after an injurious event such as cranial trauma, cerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or intracranial infection, so clinical diagnosis is usually uncomplicated. In contrast, the differential diagnosis of iNPH is more difficult2 as symptoms overlap with diseases such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease, and there are no known characteristic imaging findings for iNPH. Furthermore, iNPH is more common among the elderly and in fact is the most common form of hydrocephalus in this age group2. Timely diagnosis is essential because the clinical manifestations of iNPH and resulting sequela such as dementia can be improved through surgery. Indeed, iNPH-associated dementia is currently the only form that can be treated by surgery3. Surgery should be performed immediately upon clinical diagnosis for optimal outcome4,5,6,7,8, highlighting the importance of early diagnosis.

The main clinical symptoms of iNPH are gait disturbance, cognitive impairment, and urinary incontinence (termed Hakim’s triad), of which unsteady gait is often the primary symptom9,10. In addition, neuroimaging may reveal moderate enlargement of the ventricular system (Evan’s index > 0.3), but ventricular enlargement is generally non-obstructive as indicated by near-normal intracranial pressure. While the anterior horns of the lateral ventricles are often “blunted” in iNPH, this morphological feature may also be observed in healthy individuals. Further, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contents are normal in iNPH.

Given this non-specificity of clinical signs and symptoms, there is currently no reliable noninvasive method for the diagnosis of iNPH on presentation; rather, diagnosis most often relies on symptom abrogation following CST-TT, continuous CSF drainage, or shunt surgery performed based on clinical suspicion. In fact, many clinicians believe that clinical improvement after shunt surgery is the “gold standard” for diagnosis11. Before patients undergo shunt surgery, a CST-TT or continuous CSF drainage is usually required, both of which are invasive and carry infection risk. Moreover, these invasive procedures still do not provide rapid and definitive presurgical diagnosis.

A potential alternative for differential diagnosis is to identify neuroimaging signs specific for iNPH. Imaging examinations have become increasingly important for the diagnosis of iNPH, the post-shunt response, and prognosis12,13. Ventricular enlargement is the most reliable imaging manifestation of iNPH and can be detected using a number of imaging metrics, including Evan’s index (EI), corpus callosum angle (CA), corpus callosum height (CH), temporal angle diameter (THW), area of central lateral ventricle (CLV), and supraventricular tissue width (SVW). Among these, the EI, CMW, disproportionate ventricular enlargement (CCD), and THW have demonstrated strong diagnostic ability14,15,16,17. Several studies have also reported that intracranial volume can predict changes in cognitive function post-surgery18,19. In addition to morphological changes of the forebrain and lateral ventricles, iNPH may alter imaging manifestations within the midbrain and brainstem. Such changes could be essential predictors of outcome as these regions mediate life-sustaining regulatory functions, motor and sensory conduction from forebrain to spinal cord, sleep and wakefulness cycles, reflex activity, cranial nerve activity, emotional and behavioral regulation, muscle tension and posture control, coordinated eye movement, and language and cognitive functions.

In addition to the aforementioned clinical manifestations, patients with iNPH may experience atypical manifestations such as dizziness, headache, vertigo, hearing loss, sleep disorders, hyposmia, and personality changes. However, whether these atypical manifestations are related to changes in midbrain or brainstem structure requires further study. At present, studies on midbrain and brainstem abnormalities in iNPH have focused mainly on the flow and flow rate of the cerebral (mesencephalic) aqueduct11,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. For example, Maeda et al.21 found CSF flow voids in iNPH, but Wei et al.27 reported that aqueduct flow vacancies are not a useful indicator for iNPH diagnosis. Alternatively, Bradley et al.28 reported that increased CSF flow in the aqueduct was associated with a good shunt response, a finding helpful for both diagnosis and patient selection prior to surgery. However, Ringstad et al.20 reported that the aqueduct stroke volume did not reflect intracranial pressure pulsatility or symptom score but rather aqueduct area and ventricular volume, suggesting that aqueduct stroke volume is not a good metric for the prognosis of shunt surgery. Therefore, the relevance of these findings for diagnosis and prognosis are uncertain. Furthermore, most studies on brainstem manifestations of iNPH have not included quantitative morphological evaluations.

To identify non-invasive imaging signs for more reliable iNPH diagnosis and improved clinical decision-making, we conducted comprehensive qualitative and quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations of the brainstem and cerebral aqueduct in patients and matched healthy controls.

Research objects and methods

General information

A cross-sectional analysis was conducted from September 2021 to April 2024 on 50 patients with iNPH admitted to West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Mianyang Central Hospital, or the Third Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College (35 males, 15 females, age 62–89 years, mean age 74.58 ± 7.39 years) and 30 healthy controls (20 males, 10 females, aged 61–88 years, mean age of 73.20 ± 7.47 years). All participants received thin-section (≤ 1.0 mm) MRI examinations using 1.5-T or 3.0-T scanners. The images were reconstructed at a postprocessing center, then subjected to morphometric analyses by the study authors using 3D Slicer software (slicer.org). In the patient group, these processing and analysis steps were completed before CST-TT and surgical intervention. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (approval number: 2023 (442)), and all procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 version) and the Ethical Review Measures for Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Human Beings issued by the China Science and Technology Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent prior to examination and treatment.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients with iNPH and healthy controls.

Preset inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (i) age ≥ 60 years in accordance with the 2022 Chinese Clinical Management Guidelines for Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus, (ii) clinical manifestations including at least one of gait disturbance, cognitive impairment, or urinary incontinence, (iii) cranial CT or MRI indicating ventricular enlargement (EI ≥ 0.3 or zEI ≥ 0.42), (iv) lumbar puncture upon admission indicating an intracranial pressure ≤ 200 mmH2O), (v) no CSF abnormalities, (vi) clinical symptom improvement among patients with positive lumbar puncture test results receiving surgical treatment, (vii) height between 150 and 175 cm and weight between 50 and 70 kg, and (viii) MRI conducted prior to the CSF tap test or surgical intervention. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) not meeting the aforementioned inclusion criteria, (ii) secondary hydrocephalus, (iii) definitive diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, or progressive supranuclear palsy, (iv) presenting with other acute conditions, and (v) contraindications for MRI examination.

The inclusion criteria for healthy control participants were as follows: age ≥ 60 years, absence of clinical symptoms, no underlying medical conditions, and height between 150 and 175 cm and body weight approximately 50–70 kg. Exclusion criteria were not meeting the abovementioned inclusion criteria, unwillingness to participant, and contraindications to MRI.

Multimodal magnetic resonance imaging

Multimodal magnetic resonance images were acquired using 1.5-T and 3-T systems equipped with a head coil (vendors and models listed in Table 1). The protocols and sequence parameters are shown in Table 2. For primary localization of brainstem structures, sagittal T1-weighted (T1W) images were first acquired with a clear depiction of the cerebral aqueduct as the region of interest (ROI). Subsequently, three-dimensional thin-slice scans (≤ 1.0 mm) brainstem region were acquired in the coronal, sagittal, and axial planes using the ROI as a reference. Then, multi-planar reconstruction, image registration, and image segmentation techniques were used to construct image models of the brainstem and CSF spaces.

Data measurement and processing

All images were converted to DICOM format and imported into 3D Slicer for constructing a model including the mesencephalic aqueduct, brainstem (midbrain, pons, medulla), and periventricular CSF spaces. Measurements included cerebral aqueduct diameters at the third ventricle, constriction junction, and fourth ventricle, total aqueduct length and junction angle, morphological features of brainstem and sagittal plane areas of brainstem components and CSF spaces, various area ratios, and the angle between the brainstem and spinal cord.

Mesencephalic aqueduct measurement.

The mesencephalic (cerebral) aqueduct opens posteriorly at the back of the third ventricle and extends downwards to the opening of the fourth ventricle, passing through the periaqueductal gray matter of the midbrain. It is generally arc-shaped, and can be divided into an anterior upper segment oriented more horizontally and a posterior lower segment oriented more vertically that form a distinct angle at a junction located between the superior and inferior colliculi. The posterior segment is also wider in diameter than the upper segment.

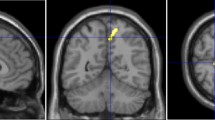

Measurements were conducted systematically in the following steps. First, DICOM-formatted images were imported into the 3D Slicer software and the “Markups” function was used to delineate the approximate shape of the cerebral aqueduct on the “OSag 3D-FIESTA” sequence images (Fig. 1a). The diameters at the opening of the third ventricle, the site of stenosis (typically located 3–4 mm from the surface of the cardiac apex), and the opening of the fourth ventricle (Fig. 1b) were measured. Concurrently, the “Link slice views” feature of 3D Slicer was used to automatically align the “OSag 3D-FIESTA” sequence images with the axial plane images, where the diameter of the cerebral aqueduct was measured again on the axial images (Fig. 1c), ensuring that the measurements obtained in the sagittal and axial planes were consistent. Then, the length of the cerebral aqueduct was measured on the “Sag 3D-FIESTA” sequence images (Fig. 1d). Finally, the angle between the anterior-superior segment and the posterior-inferior segment of the cerebral aqueduct was measured (Fig. 1e).

Analysis of mesencephalic aqueduct morphology on magnetic resonance images of the brainstem. (a) Borders of the mesencephalic aqueduct in the mid-sagittal plane. (b) Diameters of the mesencephalic aqueduct at the rostral opening with the third ventricle, constriction, and termination at the fourth ventricle. (c) Measurement of these same aqueduct diameters in the axial plane using the automatic linkage feature of 3D Slicer. (d) Length of the mesencephalic aqueduct. (e) Angle between the anterior upper and posterior lower segments of the mesencephalic aqueduct. Segments are separated by the constriction (as shown in b).

Brainstem measurements

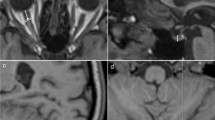

The brainstem is an irregular cylindrically shaped structure located beneath the cerebrum and connected rostrally to the diencephalon and caudally to the spinal cord at the foramen magnum. It consists of three major divisions, the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata. For quantitative measurements, a line (Line A) was drawn through the superior aperture of the pons to the inferior edge of the quadrigeminal plate and a second line (Line B) was drawn parallel to the first line but passing through the inferior aperture of the pons. A third line was drawn along the foramen magnum and defined as Line C (Line C) (Fig. 2a). The midbrain area was calculated as the area above Line A excluding the quadrigeminal plate (Fig. 2b), the pontine area as the area between the anterior and posterior edges of the pons and between Lines A and B (Fig. 2c), and the brainstem area as the sum of the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata areas (up to the foramen magnum line) (Fig. 2d). The midbrain, midbrain plus pons, and midbrain plus pons plus medulla oblongata areas were measured in the sagittal plan including the aqueduct to calculate the indicated ratios.

Analysis of brainstem areas in the sagittal plane containing the mesencephalic aqueduct. (a) Upper and low boundaries of the brainstem. Line A passes through the superior cerebellar peduncle (upper limit of the pons) and the lower edge of the quadrigeminal plate, while Line B is parallel to Line A and passes through the inferior cerebellar peduncle (lower limit of the pons). Line C is drawn along the foramen magnum (lower limit of the medulla). (b) Midbrain area above Line (A) (c) Pontine area between Lines A and (B) (d) Total brainstem area.

Midbrain area ratio

The relative size of the midbrain area was calculated as

The measurement of the sagittal plane area of the midbrain was in the same plane as the measurement of the midbrain aqueduct.

Measurement of brainstem and spinal cord angle

The angle between the brainstem and spinal cord was measured as the intersection angle of the brainstem and spinal cord middle tangents passing through the plane of the cerebral aqueduct (Fig. 3), where AB is the line along the foramen magnum, CD is the midline of the brainstem, EF is the midline of the spinal cord, and ∠A is the angle formed by the intersection of lines CD and EF.

Brainstem peri-cistern measurement

The brainstem pericistern refers to the CSF space formed around the brainstem, and is primarily an amalgamation of the interpeduncular, prepontine, pontocerebellar, pre-medullary, cerebellomedullary, occipital, and quadrigeminal cisterns (Fig. 4a). In longitudinal sections, this region mainly includes the interpeduncular, prepontine, and medullary cisterns (collectively called the prepontine cistern) (Fig. 4b), the mesencephalic aqueduct, fourth ventricle, and cerebellomedullary cistern. The lower edge is bounded by the foramen magnum.

Illustration of cisternal spaces surrounding the brainstem. (a) The total cisternal space is composed primarily of the interpeduncular, prepontine, medullary, and cerebellomedullary cisterns. The cerebral aqueduct and fourth ventricle are also shown. (b) Prepontine cistern in sagittal cross-section resembling a hammer.

Volume ratio of brainstem and peribrainstem cisterns

The brainstem-to-cistern volume ratio (BVR) was defined as the ratio of brainstem sagittal section area to peribrainstem cistern sagittal section area or.

Statistical analyses

All image-derived measures and participant characteristics were compared using SPSS software version 27. Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test for normality. Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables as [number (%)]. Continuous variables were compared between patient and healthy groups by independent samples t-tests and categorical variables by chi-squared tests. A P ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant for all tests. The sensitivity and specificity of imaging parameters for diagnostic applications were evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

Measurement results

General data results

The iNPH patient group and healthy control group did not differ in men age, sex ratio, height, or body weight (all P > 0.05) (Table 3).

Measurement of mesencephalic aqueduct

Participants from the three hospitals had aqueduct diameters, lengths, and angles that were normally distributed, and there were no significant differences in the mean diameters, lengths, or angles of the aqueducts (all P > 0.5) (Table 4). There were no significant differences in mean aqueduct diameter, length, and angle among participants from the three hospitals (all P > 0.5) (Table 5). Similarly, there were no significant pairwise differences in aqueduct length between total iNPH and healthy control groups (P > 0.05) (Table 6). However, all three aqueduct diameters were larger in patients with iNPH than healthy individuals (all P < 0.05) (Table 7) and the angle between segments was reduced (or the curvature was more pronounced) in the patient group than the healthy group (P < 0.05) (Table 8).

Brainstem measurements

In patients with iNPH, total brainstem area (comprising midbrain, pons, and medulla) at the sagittal plane including the cerebral aqueduct was significantly reduced compared to healthy individuals (P < 0.05) due to a particularly significant reduction in absolute midbrain area (P < 0.001) (Table 9) and proportional midbrain area (P < 0.001) (Table 10). In contrast, there was no significant difference in brainstem angle between patients with iNPH and healthy individuals (P > 0.05) (Table 11).

Measurement of the CSF spaces around the brainstem

In patients with iNPH, the CSF spaces around the brainstem were dilated compared to those in healthy individuals, with the prepontine cistern showing particularly significant enlargement (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5). In accord with this increase in CSF space, the brainstem to cistern volume ratio was significantly reduced in patients with iNPH (P < 0.05) (Table 12).

Measurement of prepontine cistern area

In individuals with iNPH, the dilated prepontine cistern space resembled a “hammer” in sagittal cross-section (Fig. 6a, b and c). To define this “hammer” shape qualitatively, we established the following criteria: (i) prepontine cistern area > 5 cm2, (ii) gap between the sella floor and the optic nerve > 2.5 mm (Fig. 6d, line L), (iii) interpeduncular cistern height > 5 mm (Fig. 6d, line L1), and (iv) the distance between the most prominent part of the anterior ventral brainstem and clivus > 5 mm (Fig. 6d, line L2). According to these criteria, the “hammer sign” was present in 94.0% of NPH patients but only 20.0% of healthy individuals (Table 13).

Illustration of the hammer sign as a marker for iNPH. (a) and (b) The ‘hammer’ shape of the prepontine cistern in patients with iNPH as seen on T1WI images. (c) Expansion of the prepontine cistern presents a “hammer-like” shape. (d) Line L: Gap between the sella floor and the optic nerve, Line L1: Height of the interpeduncular cistern, Line L2: Distance between the most prominent anterior ventral aspect of the brainstem and the clivus.

We also conducted ROC curve analysis to evaluate the association between the magnitude of prepontine cistern dilation and probability of the “hammer” sign (Fig. 7a). Notably, the hammer sign was associated with a significantly larger prepontine cistern area (Fig. 7b). The AUCs for iNPH patients and healthy individuals were 0.926 and 0.605, respectively. However, larger prepontine cistern area was significantly predictive of the hammer sign only in the patient group (P < 0.05) (Table 14), with a sensitivity of 94.0% and specificity of 80.0%.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of the relationship between prepontine cistern expansion magnitude and hammer sign probability in patients with iNPH and healthy controls. (a) ROC curves of prepontine cistern area in patients (red) and healthy controls (blue). (b) Box-plot showing significantly greater prepontine cistern area in patients with the hammer sign.

Discussion

Patients with iNPH present with no identifiable cause, distinguishing symptoms, or imaging features useful for differential diagnosis. Further, the characteristic triad of symptoms, gait disturbance, cognitive impairment, and urinary bladder dysfunction, is observed in only 50% of cases19. In most cases, gait disturbances, including slow movement, shuffling gait, and magnetic gait, are the earliest clinical manifestations of iNPH5 but these symptoms are shared with a myriad of acute and chronic neurological disorders. Timely differential diagnosis is critical as symptoms can be treated and often mitigated by surgery. In this study, we identify a ‘hammer sign’ on sagittal brainstem MRI associated with prepontine cistern expansion that distinguishes iNPH from healthy matched controls with high sensitivity and specificity. This hammer sign is thus an accessible and useful diagnostic feature that may facilitate timely treatment for iNPH.

Ventricular enlargement without obstruction of CSF flow is a necessary condition for the diagnosis of iNPH according to most previous studies and guidelines. In addition to dilation of the lateral, third, and fourth ventricles, iNPH is associated with expansion of the perimedullary cisterns, and we found that this expansion created an imaging marker for iNPH. Multiple pathophysiological models have been proposed to explain ventricular enlargement in iNPH2,29, including loss of ciliated ependymal cells and sheer wall stress. Ensuing dilation of the ventricles can lead to predictable changes in intracranial anatomical and angular parameters, but an EI > 0.3 is the only mandatory morphological criterion that must be met in most guidelines and expert consensus statements. In iNPH, the ventricles expand in three dimensions, so some researchers have defined directional EZ values, such as zEI30 to denote dilation of the ventricles along the longitudinal axis. However, neither the EI value nor the zEI value can differentiate hydrocephalus subtypes. Thus, additional morphological metrics must be identified and tested for diagnostic utility.

In the current study, we compared multiple morphological parameters of the mesencephalic aqueduct, brainstem, and peribrainstem cisterns between patients with iNPH and healthy age-matched controls to identify such diagnostic imaging markers. Cerebral aqueduct length did not differ between patients with iNPH and healthy individuals, but the diameter of the mesencephalic aqueduct was significantly dilated (by ~ 0.2 to ~ 0.5 mm) in the patient group. However, dilation of the mesencephalic aqueduct can be observed in both communicating hydrocephalus and obstructive hydrocephalus, including cases with obstruction below the mesencephalic aqueduct. Therefore, these changes may not be useful for distinguishing communicating from obstructive hydrocephalus. The angle of the mesencephalic aqueduct also differed between iNPH and healthy groups, being significantly steeper in patients with iNPH (resulting in a steeper horizontal to vertical transition between upper and lower segments). In other words, the curvature of the mesencephalic aqueduct is increased in patients with iNPH, and this morphological change is directly related to ventricular dilation and the disproportionately enlarged subarachnoid space hydrocephalus (DESH) sign31. Cerebrospinal fluid accumulates in the lateral fissure pool, lower part of the cerebral convexity (below the lateral fissure pool), ventral sulci, and cerebral cistern in patients with iNPH, leading to morphological changes due to accumulated pressure between the lower forebrain and upper brainstem. This change ultimately decreases the mesencephalic aqueduct angle and causes an increase in curvature.

In contrast, the angle between the brainstem and spinal cord did not differ significantly between patients with iNPH and healthy matched individuals. However, the mid-sagittal area of the brainstem was reduced in patients with iNPH compared to healthy individuals, with a particularly noticeable reduction in the cross-sectional area of the midbrain (as high as 32.4%). The midbrain serves as a bridge between the cerebrum and spinal cord, so damage manifesting as a reduction in volume may contribute to a broad spectrum of motor, sensory, emotional, and cognitive impairments. For instance, Luca et al.32 reported a significant positive correlation between the reduction in midbrain area and fluency of speech among patients with progressive supranuclear palsy. Similarly, Xiao et al.33 reported that dysfluency in speech and memory impairment in patients with iNPH were strongly associated with midbrain atrophy in addition to dysfunction of frontal–striatal circuits. Furthermore, Heikkinen et al.34 found that brainstem atrophy was associated with the extrapyramidal symptoms of frontotemporal dementia.

The total area of the cisterns surrounding the brainstem was expanded in patients with iNPH, and this was primarily the result of prepontine cistern expansion, which reached 29.7%. In the majority of patients with iNPH, this expansion of the prepontine cistern resulted in the formation of a “hammer” shape in cross-section, and ROC curve analysis revealed that the appearance of this sign was associated with greater prepontine cistern area, with a sensitivity of 94.0% and specificity of 80.0%. In other words, greater expansion of the prepontine cistern was associated with a higher probability of “hammer” sign appearance. Further, 94.0% of patients with iNPH exhibited the “hammer” sign compared to only 20.0% of healthy controls. Even among healthy individuals with the “hammer” shape, there were differences compared to patients. In patients, the distance between the posterior superior edge of the sella and the optic nerve was generally greater than 3 mm, whereas it was less than 3 mm in healthy individuals with the hammer sign.

Conclusion

Morphometric measurements of the cerebral aqueduct, brainstem, and surrounding CSF spaces in patients with iNPH and healthy matched controls revealed several imaging markers with potential diagnostic utility for iNPH. While the length of the cerebral aqueduct did not differ between patients with iNPH and healthy individuals, diameters at the aqueduct entrance, constriction, and termination were significantly larger (dilated) in the patient group. In addition, the curvature of the aqueduct was greater in patients. The total cross-sectional area of the brainstem was also reduced in patients with iNPH compared to healthy individuals, and this decrease was largely due to a substantial reduction in the cross-sectional area of the midbrain. While there was no significant difference in the angle between brainstem and spinal cord, the surrounding cerebral cisterns were dilated in patients, with the prepontine cistern exhibiting the most pronounced expansion. This dilation created a “hammer” shape in sagittal cross-section that was positively correlated with cistern area and significantly more frequent in patients than healthy controls. Future studies are needed to determine if these morphological changes are specific to iNPH and thus can be used to distinguish iNPH from other forms of communicating hydrocephalus as well as from obstructive hydrocephalus and chronic neurodegenerative diseases.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Adams, R. D., Fisher, C. M., Hakim, S., Ojemann, R. G. & Sweet, W. H. Symptomatic occult hydrocephalus with normal cerebrospinal-fluid pressure. N Engl. J. Med. 273, 117–126 (1965).

Yamada, S., Ishikawa, M. & Nozaki, K. Exploring mechanisms of ventricular enlargement in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: A role of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics and motile cilia. Fluids Barriers CNS. 18, 20 (2021).

Hydrocephalus Group of Chinese Society of Microcirculation Neurode generative Diseases Committee. Guidelines for clinical management of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus in China (2022). Chin. J. Geriatr. 41, 123–134 (2022).

Tseng, P. H. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt surgery reduces the risk of developing dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: a nationwide population-based propensity-weighted cohort study. Fluids Barriers CNS. 21, 16 (2024).

Nakajima, M. et al. Guidelines for management of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (third edition): endorsed by the Japanese society of normal pressure Hydrocephalus. Neurol. Med. Chir. (Tokyo). 61, 63–97 (2021).

Williams, M. A. & Malm, J. Diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Continuum 22, 579–599 (2016).

Pearce, R. K. B. et al. Shunting for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8, CD014923 (2024).

Torregrossa, F. et al. Health-related quality of life and role of surgical treatment in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: a systematic review. World Neurosurg. 179, 197–203e1 (2023).

Gallia, G. L., Rigamonti, D. & Williams, M. A. The diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2, 375–381 (2006).

Wallenstein, M. B. & McKhann, G. M. Salomón Hakim and the discovery of normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 67, 155–159 (2010).

Jóhannsdóttir, A. M., Pedersen, C. B., Munthe, S., Poulsen, F. R. & Jóhannsson, B. Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: validation of the DESH score as a prognostic tool for shunt surgery response. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 241, 108295 (2024).

Eide, P. K. & Pripp, A. H. Increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus patients compared to a population-based cohort from the HUNT3 survey. Fluids Barriers CNS. 11, 19 (2014).

Grasso, G., Teresi, G., Noto, M. & Torregrossa, F. Invasive preoperative investigations in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: a comprehensive review. World Neurosurg. 181, 178–183 (2024).

Bradley, W. G. Magnetic resonance imaging of normal pressure hydrocephalus. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 37, 120–128 (2016).

Suehiro, T. et al. Changes in brain morphology in patients in the preclinical stage of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Psychogeriatrics 19, 557–565 (2019).

Mantovani, P. et al. Anterior callosal angle: A new marker of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus? World Neurosurg. 139, e548–e552 (2020).

Teng, Y. Diagnostic efficacy of novel imaging markers for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus and their correlation with clinical symptoms. J. Imaging Res. Med. Appl. 6, 50–52 (2022).

Kong, S. et al. Correlation between intracranial volume parameters and cognitive impairment in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Chin. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 13, 7–12 (2022).

Kazui, H., Miyajima, M., Mori, E. & Ishikawa, M. Lumboperitoneal shunt surgery for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (SINPHONI-2): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 14, 585–594 (2015).

Ringstad, G., Emblem, K. E., Geier, O., Alperin, N. & Eide, P. K. Aqueductal stroke volume: comparisons with intracranial pressure scores in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 36, 1623–1630 (2015).

Maeda, S. et al. Biomechanical effects of hyper-dynamic cerebrospinal fluid flow through the cerebral aqueduct in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus patients. J. Biomech. 156, 111671 (2023).

Green, L. M., Wallis, T., Schuhmann, M. U. & Jaeger, M. Intracranial pressure waveform characteristics in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus and late-onset idiopathic aqueductal stenosis. Fluids Barriers CNS. 18, 25 (2021).

Yin, L. K. et al. Reversed aqueductal cerebrospinal fluid net flow in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Acta Neurol. Scand. 136, 434–439 (2017).

Ringstad, G., Emblem, K. E. & Eide, P. K. Phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging reveals net retrograde aqueductal flow in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. J. Neurosurg. 124, 1850–1857 (2016).

Sankari, S. E. et al. Correlation between tap test and CSF aqueductal stroke volume in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus, in Hydrocephalus. Acta Neurochirurgica Supplementum Vol. 113 (eds Gunes A. Aygok & Harold L. Rekate) 43–46 (Springer, 2012).

Algin, O. Role of aqueductal CSF stroke volume in idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 31, E26–E27 (2010). ; author reply E28.

Wei, Y. et al. The analysis of MRI structural imaging features in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. J. Imaging Res. Med. Appl. 4, 28–30 (2020).

Bradley, W. G. et al. Marked cerebrospinal fluid void: Indicator of successful shunt in patients with suspected normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Radiology 178, 459–466 (1991).

Mahuzier, A. et al. Ependymal cilia beating induces an actin network to protect centrioles against shear stress. Nat. Commun. 9, 2279 (2018).

Ryska, P. et al. Radiological markers of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: relative comparison of their diagnostic performance. J. Neurol. Sci. 408, 116581 (2020).

Craven, C. L., Toma, A. K., Mostafa, T., Patel, N. & Watkins, L. D. The predictive value of DESH for shunt responsiveness in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. J. Clin. Neurosci. 34, 294–298 (2016).

Luca, A. et al. Phonemic verbal fluency and midbrain atrophy in progressive supranuclear palsy. J. Alzheimers Dis. 80, 1669–1674 (2021).

Xiao, H., Hu, F., Ding, J. & Ye, Z. Cognitive impairment in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosci. Bull. 38, 1085–1096 (2022).

Heikkinen, S. et al. Brainstem atrophy is linked to extrapyramidal symptoms in frontotemporal dementia. J. Neurol. 269, 4488–4497 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Shan Wang for her assistance in data collection. The authors also thank LetPub (www.letpub.com.cn/) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 82201502, and it also supported by Sichuan Province Medical Research Project S22078 from Sichuan Medical Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Liangxue Zhou designed the experiment. Kui Xiao and Xielin Tang conducted the experiment. Shenghua Liu, Ziang Deng, and Feilong Yang performed the statistical analysis, and Ziang Deng was responsible for medical ethics applications.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, K., Zhou, L., Tang, X. et al. MRI imaging characteristics of brainstem and midbrain aqueduct in patients with iNPH. Sci Rep 15, 94 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83874-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83874-7