Abstract

The concept of friction was integrated into the broader field of tribology in the 20th century. Here, we revive the older friction coefficient concept and show that it is the defining parameter for a family of granular materials. We show, for the first time, that kinetic friction coefficients of such systems can be described as a function of the lubricating fluid and the shape of the granules, without any fitting parameters. With this, we define the value and conditions for the minimal friction of this system and show how it can increase depending on the properties of the system. This paper shows that the minimum possible friction for an assembly of granular media is the same universal constant of ¼ that da Vinci identified for kinetic friction between two rigid bodies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leonardo da Vinci obtained the concept of friction coefficient1,2,3,4,5 at a time in which “it was believed that all friction coefficients were exactly ¼, with values different from ¼ reflecting some “nonideal” behavior of the system”3. Later, Amontons established that friction forces indeed increase linearly with the normal load while the friction coefficients can obtain any value. The next milestone was due to David Tabor who showed that the contact area is, in fact, the parameter that determines the friction force while the Amontons law is a special case for which the area increases roughly linearly with the load1,2. While Tabor’s understanding is still valid, it does not address lubrication, which is the crucial element from an engineering and economic perspective. A central pillar that addresses this aspect is the Stribeck curve6,7,8,9,10 that generalizes the static and dynamic friction to be a part of a continuous curve in which the determining parameters include the sliding velocity, the viscosity of the lubricating fluid, and the normal load. The curve starts with a high (static) friction coefficient, which gradually decreases as the velocity and viscosity of the system increase, until some minimal value after which it increases. This minimal value is of special interest since it defines the conditions in which machines operate in their most efficient, most environmental and most sustainable mode. However, in most cases, the Stribeck curve can only be drawn qualitatively, and especially, as there is no mathematical prediction for the most crucial, minimal friction, value within this curve.

Here, we present the first mathematical prediction for the minimal value of the friction coefficient and its increase as part of the Stribeck curve for a given physical system, specifically the system of lubricated granular media for which surface forces are negligible. Surprisingly, the minimal possible friction coefficient obtained appears to be a universal constant that is not a function of the system’s parameters, but can be extrapolated from them. This friction coefficient value is close to the result idealized by Da Vinci through his wood experiments4, which suggests that they may have included granular debris, though this was not mentioned specifically.

Brief introduction to granular media

In general, granular media is a multiphase material which comprises of grains, gases and/or liquids that fill the space between the granules11,12,13,14,15. In granular media, the friction properties are known to be associated with the morphology of the interfaces of the grains, as particles with rougher and less regular shapes create higher friction16,17,18,19,20,21. In the presence of lubricants, the friction reduces due to a lubricating layer that is created between solid surfaces6,7,8,9,10, which assists in overcoming kinematic constraints resulting from particle imperfections22. The intricate relations of the friction force with other parameters can also reduce to a constant kinetic friction coefficient, as shown in the recent letter by Fielding23, who also explained an interesting aging effect that is similar to that observed in drops24.

That roughly constant kinetic friction coefficient is reminiscent of the observation in this paper, where the friction coefficient is not only constant, but converges close to a rational number, ¼. This extrapolated constant is independent of the applied load, the viscosity of the lubricating liquid, or the morphology of the granules.

Experimental methods

We used various granular compositions including sand, quartz beads and crushed glass, under various grain size distributions and morphologies to account for a wide range of friction coefficients. Microscope images of some of the grain morphologies are shown in Fig. 1. Examples of shear tests performed on samples such as those shown in Fig. 1a are presented in Fig. 2.

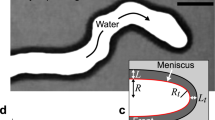

Figure 2 considers experiments in which granular assemblies are being sheared at a (predefined) horizontal plane, during which the shear forces, T, and volumetric changes, Δv, are continuously measured throughout the horizontal displacement, Δh. Figure 2A presents the volumetric changes that result from the shear tests performed with the instrument that is sketched in Fig. 2B, and Fig. 2C presents the corresponding changes in the shear force. These shear patterns monitor the development of the lateral forces that occur upon a failure plane in granular assemblies that are sheared under constant normal forces, N. The tests were performed on liquid-saturated samples (see Table S1 of the supplementary material for full list of liquids used in this study and Table S2 for the full list of the friction coefficients of the different systems) so that capillary forces (or suction stresses) between the granules are not expected to develop25,26,27. The samples are sheared at a constant rate of 2 mm/min, a velocity of an order that is sufficiently low so as not to affect the friction coefficient in such systems28.

Shear test results of granular media under different normal forces, exemplified for the case of uniform glass spheres (presented in Fig. 1a). (A) Vertical displacement of the upper plate against the horizontal displacement during the shear test, (B) a schematic illustration of the shear test apparatus and the directions of the forces and displacements, (C) shear force response versus horizontal displacement, and (D) the obtained critical shear force against the applied normal force.

We see in Fig. 2A that, as the shear force develops, the volume can either increase or decrease, i.e. the upper surface is either pushed vertically up or down with the progression of the horizontal translation. As this happens, the shear forces presented in Fig. 2C increase and sometimes decrease again as the granules rearrange themselves in their steady shear state. Eventually, the shear forces reach a plateau, which corresponds to a cessation of volumetric changes, as evident from Fig. 2A. The increase or decrease in the sample volume during the test depends on both the initial porosity of the granular media and the applied normal force. However, the converged shear force (which we consider in this study) depends only on the normal force (Fig. 2D), and therefore, the initial porosity is not relevant in this study. For example, the black and the orange traces in Fig. 2A correspond to two samples under the same normal force (0.5 kN) and experience quite different volumetric changes (as associated with different initial porosities), yet their eventual shear force responses converge to a similar (critical) value, validating the robustness of our force responses (note that the y axis in Fig. 2A corresponds to the change in volume, not the volume itself). This critical volume cessation is commonly known as the critical-state principle in soil mechanics29,30,31.

We focus on the friction force, T, that corresponds to that steady state plateau (kinetic friction), which is presented in Fig. 2D as a function of the normal forces, N. Note that their ratio, in our case, is identical to the ratio of the corresponding stresses (\(\:\mu\:=\frac{T}{N}=\frac{\tau\:}{\sigma\:}\), where \(\:\sigma\:\) and \(\:\tau\:\) are the normal and shear stresses applied on the sample and \(\:\mu\:\) is the friction coefficient).

Results

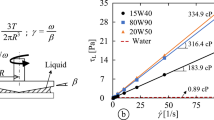

From slopes of curves such as that shown in Fig. 2D, we plot in Fig. 3A the friction coefficients of the liquid-saturated samples, µl, versus the friction coefficients of the same granular configuration in a dry state, µd. Since the granules are macroscopic and have high rigidity, the attractive surface forces in these systems are negligible compared to the body forces and so is the dissipation associated with the plastic deformation of the granules13,32,33,34,35,36,37. This choice of materials was made so that the geometric differences between the granules and the lubricating liquids would be the only two significant factors which directly affect the friction coefficient of the granular assemblies. Thus, the closer is our system to perfectly rigid conditions the closer one can consider the friction coefficients in dry conditions as an index expressing the granular morphologies. The difference between the slopes is associated with the viscosity of the liquid media. We see that the higher the viscosity of the liquids, the lower are the slopes of the linear curves and the lower are the friction coefficients for the same granules. As the viscosity goes down, the lubricating effect of the liquids diminishes, until, from a certain viscosity downward, the effect of the liquid’s viscosity is hardly noticeable. For example, the friction coefficients of granules saturated with water has no detectable difference from that of the same granules lubricated by air which is 50 times less viscous38. Yet, the more striking observation in Fig. 3A is the intersection of all curves to a single friction coefficient, which happens to be in the vicinity of ¼. In this intersection point, where all the linear µl trends intersect, there is no effect of lubrication on the friction property; i.e., µl = µd regardless of the lubricating agent. From this point onward, the lubrication effect is amplified for higher friction samples.

In Fig. 3B we plot the friction coefficients associated with distinctive granular configurations against the log of the liquid viscosities, η, that saturate these granular media. The slopes of the different trends in the figure decrease for granules that have lower µd values, until an almost horizontal trend which is obtained for the smoothest monodispersed spherical assembly (having the lowest µd value). The theoretical horizontal line of µ = ¼ in the figure represents the special case of ideal sample that is unaffected by lubrication effects, which is equivalent to the intersection point described in Fig. 3A.

Relation between µl and the properties of the media. (A) µl as a function of µd. Different lines correspond to different lubricants, while different µd values correspond to different granular morphologies. (B) µl as a function of η. Different lines correspond to different granular morphologies whose dry friction coefficients are marked by open symbols on the leftmost y axis.

It is known that higher friction is associated with rougher and less regular granular shapes, which is attributed to particle interlocking phenomena11,17,18,19,20,21. Indeed, the intersection point in Fig. 3A is close to our smoothest perfectly spherical granules. The plots also suggest that the lowest obtainable friction coefficient for such systems is close to ¼. The convergence to this value occurs in two different extrapolations:

-

1.

If we plot the wet friction coefficient as a function of the dry one, all curves intersect at that value.

-

2.

If we plot the wet friction coefficient as a function of the log of the viscosity of the lubricating liquids. This extrapolation gives rise to some threshold viscosity value for which the friction coefficient is again close to ¼ regardless of the shape of the granules. The value of this viscosity is ~ 105cP, and the reason for this viscosity to be the theoretical number to which all curves merge is a subject of future studies.

It is noteworthy that these observations are valid for the examined system, which consists of a granular assembly with randomly oriented particles at the critical state of shearing, where no further volume changes occur. Using quartz grains, we were able to produce a wide range of friction values (ranging from 0.25 to 0.72) associated with different grain morphologies and structures, from which the (constant) minimum friction of 0.25 was determined by extrapolation. Since this minimum friction threshold was also directly measured using an assembly of uniform 1 mm quartz spheres, additional shearing tests were conducted on similar assemblies of 1 ± 0.02 mm smooth spheres composed of different grain minerals—copper, stainless steel, and chromium—to examine the effect of grain mineralogy. The friction values measured for these granular materials are 0.26, 0.27, and 0.27, respectively. However, even if these slight deviations from the 0.25 friction value (in quartz) may be attributed to differences in mineral type, they are still secondary to the substantial influence of grain morphologies and the assembly structure.

Discussion and analysis

The frictional property examined in this study pertains to a granular assembly, where the friction response results from the cumulative intergranular forces developed among multiple particles along a shear plane. Specifically, the minimum friction value of ¼ is considered universal to this particular system, though lower friction values may be observed in other systems (such as for individual grains shearing39,40 or grains assembly sheared against plate11, etc.). Although the value of µ = ¼ was directly measured in a setup of uniform, smooth, and rigid spheres (regardless of lubricant type), its determination as a universal constant is based on extrapolating results across a wide range of lubricated granular assemblies. Additionally, the presence of a minimum (threshold) friction value aligns with the behavior described by the Stribeck curve, which illustrates the variation in friction properties for a given system, with a well-defined absolute minimal friction threshold. Therefore, similar to the behavior of the Stribeck curve, it can be assumed (and warrants further study) that higher friction values would occur if the system were subjected to increased shear rates.

Both increasing the lubricant’s viscosity and using granules with a smoother surface and more spherical geometry reduce the resultant friction of the granule’s assembly. Yet, though the two are decoupled, they seem to have a similar origin since the use of higher viscosity liquids affects the solid particles as if they were spherical, and the use of spherical particles affects the solid particles as if they were in a high viscosity fluid while the two are not directly superimposed. Rather, both converge to the same friction coefficient value, namely the higher is their individual influence the smaller is their mutual superimposed influence. A schematic illustration that explains how this effect can materialize is shown in Fig. 4, where the viscous liquid smoothly thickens the pseudo-outline of the particles’ shape so that an assembly of such particles is associated with the lowest friction value that corresponds to spherical granules. The state in which solid particles behave as if they were spherical aligns with the concept of a somewhat theoretical viscosity (Fig. 3B), where the friction is unaffected by the grains’ morphologies. The existence of this threshold viscosity value, associated with minimal friction, reflects the behavior of the Stribeck curve, which defines a fundamental (minimal) friction for a given system.

This experimental paper does not provide a theoretical analysis, but we note that relating the convergence of the friction coefficient of ¼ to monodispersed spherical geometry suggests that the friction involves granules rolling on each other19,21,41,42. While the kinematics of an ideal sample with smooth, spherical particles could be studied through microstructural geometry changes, the friction values in this work are tied to chaotic microscale kinematics (involves shearing with no net volume change, where particles alternately rise and sink, maintaining zero average elevation within the shear plane). Further study is recommended to link these microscale kinematics to the findings presented here.

In light of the friction threshold of ¼ and the consistent friction trends in Fig. 3A and B, the friction coefficient of lubricated granular assembly can be described as:

This equation expresses the both the effect of the lubricant viscosity, \(\:{\eta\:}_{l},\) and that of the grain shape, described indirectly through \(\:{\mu\:}_{d}\), on the friction coefficient of rigid granular media. The expression \(\:\alpha\:\left({\mu\:}_{d}-\text{1/4}\right)\:log\left({\eta\:}_{l}/{\eta\:}_{w}\right)\) defines the lubrication effect in terms of friction reduction in the presence of liquid. The logarithmic dependence on \(\:{\eta\:}_{l}\), which is depicted is Fig. 3B, is expressed in relation to the viscosity of water, \(\:{\eta\:}_{w}\), which is given as a reference index due to the similar mechanical behavior of dry and water-saturated granular samples; i.e., \(\:{\mu\:}_{l=water}\approx\:{\mu\:}_{d}\) when \(\:{\eta\:}_{l}={\eta\:}_{w}\). The offset \(\:{\mu\:}_{d}-{1/4}\) describes the degree of morphological grains imperfection, which is linearly related to \(\:{\mu\:}_{l}\) (Fig. 3A). It can be seen that \(\:{\mu\:}_{l}\) converges to \(\:{\mu\:}_{d}\) as \(\:{\mu\:}_{d}\) gets closer to ¼. The coefficient α multiplies the coupled effect of the grain shape and the liquid viscosity. It is proved herein, that the value of α is constant, with zero degrees of freedom, which satisfies \(\:{\mu\:}_{l}\)= \(\:{\mu\:}_{d}\) = ¼ when \(\:{\eta\:}_{l}\) converges to the presented theoretical viscosity, \(\:{\eta\:}^{*}\). In our system, \(\:\alpha\:=1/log\left({\eta\:}^{*}/{\eta\:}_{w}\right)\:\)~ 0.2. Figure 5 shows the good agreement between the experimental results and Eq. (1)’s prediction, which does not include any free parameter.

The experimentally obtained µl against the predicted friction values (Eq. 1).

Conclusion

The minimal friction coefficient of a system of sheared granular assembly converges to a single value close to ¼ regardless of the lubricant used or the shape of the granules. The constant friction value of ¼ closely obtained for such ideal granules aligns with the common belief during da Vinci’s time that all friction coefficients were exactly ¼, where deviations from this value were thought to indicate some ‘nonideal’ behavior of the system3.

We extrapolate the friction coefficient to this value in two different ways:

-

1.

By expressing the non-uniformity of the granules through their friction coefficient in dry medium. We show that regardless of the lubricant used, the friction coefficients of lubricated, but different, granules align on straight lines of different slopes, and all curves meet close to µ = ¼. The most spherical, monodispersed, smooth granules reach the value that is closest to ¼, and, for these granules, the effect of the lubricants is negligible.

-

2.

By plotting the friction coefficient of the same granules as a function of the viscosities of the different lubricating liquids. We obtain different slopes for different granules, having steeper slopes for less-regular granule shapes. Yet, all curves meet again in the vicinity of µ = ¼. This happens at a viscosity of \(\:{\eta\:}^{*}\)~105cP. The meaning of this theoretical viscosity is a subject of further studies.

It should be highlighted that these conclusions apply solely to an assembly of rigid and macroscopic granules, given that the impact of their deformation is negligible in this study since the stresses applied are significantly lower than the stiffness of the granules.

Friction values close to ¼ appeared frequently over the history3,4,43, but our study is the first to generalize it and relate it to different physical systems of the same family. We show that such a value is characteristic to granular matter of perfectly spherical geometry and can be concluded from measurements of other granular media, including granular geometries that are far from spherical shapes and spanning over at least 5 orders of magnitude of the viscosity of the liquid between the granules. Based on this, we present an equation that predicts the friction of granular media, incorporating the coupled effect of grain shapes and lubricant viscosities. The equation has zero degrees of freedom, and the model can serve as a foundation for further scientific developments and engineering applications.

Data availability

The properties and analysis of the materials used in this study are detailed in the Supplementary Information file. All analyzed data are presented within the manuscript. The raw experimental data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dowson, D. History of Tribology (Longman, 1979).

Bowden, F. P. & Tabor, D. The Friction and Lubrication of Solids, ed. 1 (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Israelachvili, J. N. Intermolecular Surface Forces ed. 3 (Academic, 2010).

Pitenis, A., Dowson, D., Gregory, W. & Sawyer Leonardo Da Vinci’s friction experiments: An old story acknowledged and repeated. Tribol. Lett. 56, 509–515 (2014).

Hutchings, I. M. Leonardo Da Vinci ’ s studies of friction. Wear 360–361, 51–66 (2016).

Hamrock, B. J., Schmid, S. R. & Jacobson, B. O. Fundamentals of Fluid Film Lubrication (CRC Press, 2004).

Zhu, D., Wang, J. & Wang, Q. J. On the stribeck curves for lubricated counterformal contacts of rough surfaces. J. Tribol. 137 (2015).

Zhang, Y., Biboulet, N., Venner, C. H. & Lubrecht, A. A. Prediction of the Stribeck curve under full-film elastohydrodynamic lubrication. Tribol. Int. 149, 105569 (2020).

Veltkamp, B., Velikov, K. P., Venner, C. H. & Bonn, D. Lubricated friction and the Hersey number. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 44301 (2021).

Hasan, S., Kordijazi, A., Rohatgi, P. K. & Nosonovsky, M. Tribology international machine learning models of the transition from solid to liquid lubricated friction and wear in aluminum-graphite composites. Tribol. Int. 165, 107326 (2022).

Rowe, P. W. The stress-dilatancy relation for static equilibrium of an assembly of particles in contact. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 269, 500–527. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1962.0193) (1962).

Jaeger, H. M. & Nagel, S. R. Physics of the granular state. Science 255, 1523–1531 (1992).

Santamarina, J. C. Soil behavior at the microscale: particle forces. In Soil Behavior and Soft Ground Construction (J. T. Germaine, T. C. Sheahan, R. V Whitman, Eds), pp. 25–56 (ASCE, 2003).

Castellanos, A. The relationship between attractive interparticle forces and bulk behaviour in dry and uncharged fine powders. Adv. Phys. 54, 263–376 (2005).

Behringer, R. & Chakraborty, B. The physics of jamming for granular materials: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 82, 012601 (2019).

Cho, G. C., Dodds, J. & Santamarina, C. Particle shape effects on packing density, stiffness, and strength:natural and crushed sands. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 132, 591–602 (2006).

Guo, P. & Su, X. Shear strength, interparticle locking, and dilatancy of granular materials. Can. Geotech. J. 44, 579–591 (2007).

Härtl, J. & Ooi, J. Y. Experiments and simulations of direct shear tests: porosity, contact friction and bulk friction. Granul. Matter 10, 263–271 (2008).

Santamarina, J. C. & Shin, H. Friction in Granular Media (2009).

Thakur, M. M. & Penumadu, D. Influence of friction and particle morphology on triaxial shearing of granular materials. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 147, 1–15 (2021).

Lakkimsetti, B. & Latha, M. Grain shape effects on the liquefaction response of geotextile – reinforced sands. Int. J. Geosynth. Gr. Eng. 9, 1–17 (2023).

Meegoda, J. N., Chen, B., Gunasekera, S. D. & Pederson, P. Compaction characteristics of contaminated soils-reuse as a road base material. Geotech. Spec. Publ. 195–209 (1998).

Fielding, S. M. Model of friction with plastic contact nudging: Amontons-Coulomb laws, aging of static friction, and Nonmonotonic Stribeck curves with Finite Quasistatic Limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 178203 (2023).

Tadmor, R., Janik, J., Klein, J. & Fetters, L. J. Sliding friction with polymer brushes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 2–5 (2003).

Bishop, A. W. The principle of effective stress. Tek Ukebl 39, 859–863 (1959).

Mitarai, N. & Nori, F. Wet granular materials. Adv. Phys. 55, 1–45 (2006).

Lu, N. & Likos, W. J. Suction stress characteristic curve for Unsaturated Soil. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 132, 131–142 (2006).

Miron, A., Tadmor, R. & Pinkert, S. Decoupling the mechanical role of pore liquids in soils to liquid viscous effect and solid–liquid adhesion effect. Acta Geotech. 18, 1–10 (2022).

Schofield, A. N. & Wroth, P. Critical State Soil Mechanics 310 (1968).

Bolton, M. D. The strength and dilatancy of sands. Géotechnique 36, 65–78 (1986).

Ratnaweera, P. & Meegoda, J. N. Shear strength and stress-strain behavior of contaminated soils. Geotech. Test. J. 29, 1–8 (2006).

Mitchell, J. K. & Soga, K. Fundamentals of Soil Behavior, ed. 3 (Wiley, 2005).

Brizmer, V., Kligerman, Y. & Etsion, I. Elastic–plastic spherical contact under combined normal and tangential loading in full stick. Tribol. Lett. 25, 61–70 (2007).

Cohen, D., Kligerman, Y. & Etsion, I. A model for contact and static friction of nominally flat Rough surfaces under full stick contact condition. J. Tribol. 130 (2008).

Ovcharenko, A., Halperin, G. & Etsion, I. Experimental Study of adhesive static friction in a spherical elastic-plastic contact. J. Tribol. 130 (2008).

Singh, S. K., Srivastava, R. K. & John, S. Studies on soil contamination due to used motor oil and its remediation. Can. Geotech. J. 46, 1077–1083 (2009).

Wang, X., Liu, Y. & Yu, P. Upscaling critical state considering the distribution of meso-structures in granular materials. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 45, 1624–1646 (2021).

Dai, B. B., Yang, J. & Zhou, C. Y. Observed effects of interparticle friction and particle size on shear behavior of granular materials. Int. J. Geomech. 16, 04015011 (2016).

Cavarretta, I., Rocchi, I. & Coop, M. R. A new interparticle friction apparatus for granular materials. Can. Geotech. J. 48, 1829–1840 (2011).

Li, Y., Chan, D. & Nouri, A. Measuring interparticle friction of granules for micromechanical modeling. Energies 15, 1–11 (2022).

Vangla, P., Roy, N. & Gali, M. L. Image based shape characterization of granular materials and its effect on kinematics of particle motion. Granul. Matter 20, 1–19 (2018).

Mair, K., Frye, K. M. & Marone, C. Influence of grain characteristics on the friction of granular shear zones. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 107, 1–9 (2002).

Etsion, I. Comment on Leonardo Da Vinci ’ s friction experiments: An old story acknowledged and repeated. Tribol. Lett. 58, 33 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We benefited from useful discussions with Roman Goltsberg. RT thanks Pazy foundation, Israel, for partial support of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. M., S.P., and R.T. conceptualized this study, conducted the analysis and wrote the main manuscript text. A.M. performed the laboratory experiments. S.P. and R.T. are the PIs of this research.V.M. and A.M. prepared Fig. 1. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miron, A., Tadmor, R., Multanen, V. et al. Da Vinci’s friction for granular media. Sci Rep 15, 791 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83889-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83889-0

This article is cited by

-

Friction of granular systems: the role of solid–liquid interaction

Scientific Reports (2025)