Abstract

Hybrid maize seed production in Africa is dependent upon manual detasseling of the female parental lines, often resulting in plant damage that can lead to reduced seed yields on those detasseled lines. Additionally, incomplete detasseling can result in hybrid purity issues that can lead to production fields being rejected. A unique nuclear genetic male sterility seed production technology, referred to as Ms44-SPT, was developed to avoid hybrid seed loss and to improve the purity and quality of hybrid maize production. Hybrid seed yield reduction following detasseling can be attributed to leaf loss. Our analyses showed an average 2.9 leaves are lost during the detasseling process, resulting in a seed yield reduction of 14.0%. These findings suggest that deploying the Ms44-SPT technology would avoid this seed yield loss. By simplifying hybrid production and increasing seed yields, Ms44-SPT could help drive hybrid replacement, providing smallholder farmers with better access to improved hybrids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A steady stream of incrementally improved varieties has been an important strategy to increase cereal yields in an increasingly variable climate1,2. New maize hybrids offer yield gains to farmers, particularly in stress prone environments3,4,5. Over the past two decades there has been extensive investment in strengthening national and regional maize breeding programs in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)6. The estimated area planted with new stress tolerant maize hybrids across eight countries in eastern and southern Africa (ESA) increased from 1.4 million hectares (M ha) in 2016 to 4.9 M ha in 2021 to 7 M ha in 20237,8. The average area-weighted age of maize hybrids provides a measure of the rate of hybrid replacement9. While the average area-weighted age of maize hybrids in ESA has reduced to approximately 10 years8, private seed companies often remain hesitant to continuously update their hybrid portfolio. Key assumptions of market-led strategies to improve the livelihoods of smallholder farmers through the adoption of improved maize hybrids are that: a) seed companies, and farmers, see the value in adopting new hybrids; and b) seed companies are willing and able to continuously introduce new hybrids whilst phasing out older/obsolete hybrids10.

Demand for improved genetics alone does not appear to be a sufficient driver for the private sector to continuously replace maize hybrids11. Replacing older hybrids is expensive, complex, and time-consuming for seed companies2,12. Seed companies need to cover the cost of new hybrid release requirements and produce seed of the new hybrid for commercialisation, demonstration, and marketing requirements, whilst in parallel continuing seed production of the older hybrid to be phased out. While in other regions of the world, farmers demand new maize hybrids and very short product life cycles (< 5 years)13, this is not the case in SSA. The combination of complexity, high cost and associated financial risk is a deterrent to continued maize hybrid replacement by the private sector, and likely accounts, in part, for the continued sale of old/obsolete hybrids2.

Since farmer demand and intense competition for market share are currently not sufficiently driving hybrid replacement strategies in SSA, alternative drivers are required to facilitate hybrid turnover. The emergence of new diseases or pests has been one such driver of crop varietal replacement in the region14,15. Additionally, technological innovations which provide direct economic benefits to seed companies could also help drive hybrid replacement16,17.

Hybrid maize seed is produced by cross-pollinating two genetically distinct parents in isolated seed production fields. The tassel is removed from female parent plants to prevent self-pollination (a process referred to as detasseling), thus ensuring only pollen from male parent plants fertilizes female plants. Three-way hybrids dominate the commercial maize market in SSA8,18; thus, two hybridization steps, and consequently two detasseling steps, are required. Manual detasseling often reduces hybrid seed production yields due to inadvertent removal of leaves below the tassel. The loss of one leaf (plus tassel) was previously estimated to reduce hybrid seed production yields by 2.6%, whilst the removal of four leaves reduced seed production yields by 25.4%19. Genetic male sterility systems offer an alternative approach in hybrid maize seed production, avoiding the need to detassel, reducing the risk of self-pollination20, and reducing yield loss during hybrid seed production. Cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) has been used since the 1950s to produce hybrid maize seed21, although it does not work across all genetic backgrounds and is influenced by the environment21. CMS can also be difficult to use in producing three-way hybrids because two non-restoring male parents must be used, the first to increase male-sterile seed of the initial female parent, and the second to produce male-sterile seed of the single-cross female parent. A further complication is the need to use a fully fertility-restoring male parent in the production of the final three-way hybrid seed.

Nuclear genetic male sterility, which is more stable across genetic backgrounds and environments, has been used more recently to produce hybrid maize seed22,23. Corteva Agriscience® developed a nuclear genetic male sterility system, Seed Production Technology (SPT), based on the recessive maize male sterility gene, ms45, for hybrid maize production in the USA24. The seed production technology for Africa (SPTA) project later introduced the dominant maize male sterility gene, Ms4418. Because Ms44 is dominant it is more suitable for three-way hybrid production as both the initial inbred female parent and the single-cross female parent are non-pollen producing (NPP). The need for detasseling during both hybridization steps, therefore, is eliminated (Fig. 1). Although a transgenic maintainer line is used to propagate the initial NPP female lines, the resulting inbred is not only non-pollen producing (INP), but it is also non-transgenic. This is a consequence of three linked components in the transgenic maintainer line. One component enables fertility of the maintainer line. A second component blocks inheritance of the entire maintainer construct through the pollen by pollen-specific expression of a gene that eliminates starch formation in pollen grains carrying the maintainer transgenic components24. A third component results in seed containing the maintainer transgenes to become reddish pink. To ensure that all progenies are non-GM, the initial female parent seed is run through a colour sorter as a final quality control step22. The transgenic maintainer components have gone through regulatory approval in both the USA and South Africa, ensuring they are safe for the public and the environment. The final hybrid maize seed sold to farmers, as well as the parental lines used by seed companies, is non-GM. Only the maintainer line is transgenic.

Three-way hybrid maize seed production using Ms44-Seed Production Technology (Ms44-SPTA). In Season 1, male and female parent inbred lines are planted in the seed production field to produce the single-cross. The non-transgenic female parent inbred line (Line A) has been converted to become homozygous for Ms44. It is referred to as inbred non-pollen producing (INP). The resulting single-cross, which is now heterozygous for Ms44, is referred to as heterozygous non-pollen producing (HNP). In Season 2, the HNP (single-cross female) and male inbred line (Line C) are planted in the seed production field to produce the final three-way hybrid. The resulting three-way hybrid segregates 50:50 for Ms44 and is referred to as 50% non-pollen producing (FNP).

We estimated the seed yield benefit of using the Ms44 nuclear genetic male sterility-based seed production technology, referred hereafter as Ms44-SPT, in hybrid maize seed production. To quantify seed production loss associated with leaf removal during detasseling we conducted a series of experiments using PP (pollen producing) and NPP single-cross female parent. In PP single cross female parents up to five leaves were removed. NPP single cross female parents were produced using the Ms44-SPT. To estimate actual leaf loss in seed production fields during the detasseling process, the number of leaves removed in commercial seed production fields were quantified. This allowed the average reduction in female seed production yields to be quantified.

Results

Maize seed yield reduction associated with leaf removal

The first trial consisted of two experiments. In the first experiment (where one leaf was removed from PP single-cross parents), average seed yield across locations ranged from 2.4 to 15.3 t ha−1, at an average of 7.26 t ha−1 across locations (Fig. 2, Trial1-exp 1). In the second experiment where one or three leaves were removed, the average seed yield ranged from 2.35 to 10.1 t ha−1, at an average of 5.27 t ha−1 across locations (Fig. 2, Trial 1-exp 2). In the second trial (where one to five leaves were removed from the PP single cross parents), average seed yield across locations ranged from 3.78 to 8.37 t ha−1, at an average of 6.29 t ha−1 across locations (Fig. 2, Trial 2). Seed yield reduction was consistent across different entries (Fig. 3).

Average seed yield of Trial 1, Experiment 1 (Trial 1-exp 1) where one leaf was removed from the pollen-producing (PP) single-cross parents; Trial 1, Experiment 2 (Trial 1-exp 2) where one or three leaves were removed from the PP single-cross parents, and Trial 2 where one to five leaves were removed from the PP single-cross parents. Grey circles represent individual data points, and coloured circles represent the average seed yield at each location. The colour refers to the number of leaves removed.

Average seed yield of Trial 1 (where one or three leaves were removed from the pollen-producing (PP) single-cross parents) and Trial 2 (where one to five leaves were removed from the PP single-cross parents) across pedigrees. Grey circles represent individual data points and coloured circles represent the average seed yield at each location. The colour refers to the number of leaves removed.

Quantifying female seed loss associated with leaf removal during detasseling

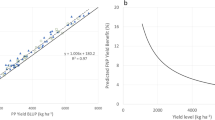

Overall, a significant reduction (n = 1009, p-value = 0.000999) in yield was observed per leaf removed in the first trial. The change in yield per leaf removed was estimated to be −0.37 (−0.58, −0.28) t ha−1 (Fig. 4), corresponding to a yield reduction of 5.2% per leaf. The change in yield per leaf removed in the second trial was also significant (n = 283, p-value = 0.000999). Yield was reduced by −0.28 (−0.36, −0.20) t ha−1 (Fig. 4) per leaf removed, with a corresponding yield reduction of 4.0%. Compared to the first trial, the yield reductions were attenuated in the second trial, an effect which is largely due to the smaller effects observed in this trial for removal of two and three leaves (Fig. 4).

The (a) actual change in seed yield across all experiments (Joint) and (b) relative seed yield reduction per leaf removed in Trial 1, where one leaf (experiment one) and three leaves (experiment two) were removed from the pollen producing parent, and Trial 2 where up to five leaves were removed from the pollen producing parent and combined across all trials.

When data was combined across the two trials in a joint analysis, we found a significant change (n = 1292, p-value = 0.000999) in yield of -0.33 t ha−1 (−0.49, −0.24), corresponding to a yield reduction of 4.8%, which is primarily driven by the effects observed in trial 1 due to the significantly larger sample size (Fig. 5). There was also a significant amount of variability observed in the effect of removing a single leaf. The estimated standard deviation of the random slope was 0.18, 0.10, and 0.13 in the models for trial one, trial 2, and the joint model respectively. When we incorporate the random effects for year-location and pedigree to obtain cluster specific effects, the estimates of the impact of removing one leaf range from −0.48 to −0.16 t ha−1 and the percent yield reductions ranged from −16.3 to −1.6% per leaf removed (Fig. 5).

Estimated change on yield in Trial 1 (where one leaf (experiment one) and one or three leaves were removed from the pollen producing parent (experiment two)), and Trial 2 (where up to five leaves were removed from the pollen producing parent) and combined across all trials. The size of the bubble represents the number of observations. In the joint (combined) analysis, data from Trial 1 is indicated by a triangle and data from Trial 2 two is indicated by a triangle (and referred to as Joint).

Seed size and weight

Less than 30.0% of PP and NPP seed was classified as round (Table 1). The largest seed grade in both PP and NPP was medium flat, accounting for 41.0 and 41.7% of the total seed, respectively. Within each class, there was no significant difference between the number of kernels produced in both the NPP and PP after adjusting for multiple comparisons using Holm-Sidak, except for large round grade (n = 680, p-value < 0.05). PP had more large round kernels. Similarly, for 100-kernel weight of each seed grade there were no significant difference after adjusting for multiple comparisons using Holm-Sidak, except for the large round grade (n = 680, p-value < 0.05). PP had a model estimated mean weight of 31.46 g and NPP 22.50 g. However, this was the smallest class, accounting for 1.8 and 2.4% of kernels in the NPP and PP respectively.

Leaf removal in commercial hybrid maize seed production fields and estimated yield reduction associated with detasseling

The distribution of top leaves removed during the detasseling process in three-way hybrid maize production was similar across nine commercial seed production fields (Fig. 6). Approximately 35.9% of removed tassels had three leaves attached. Over six percent of tassels (6.4%) had five or more leaves attached. A further 3.9% of tassels had no leaves attached. The highest number of leaves attached to the tassel was nine, although this only was observed on four tassels (Fig. 6). Across locations, an average of 2.81 leaves were removed during detasseling. Using the joint model described above the yield change in the typical location is predicted to be −0.97 t ha−1, which corresponds to a 14.0% reduction in yield. Considering the uncertainty in the fixed effect estimates, the random effects variability, and the distribution of leaves removed during detasseling in commercial hybrid maize seed production fields we simulated yields to obtain a predictive distribution of yield reduction. The mean yield reduction in these simulations was 17.0%, the median yield reduction was 12.6 and a 95% predictive interval of 62.0 to 0%.

Discussion

This is the first documented study in Africa to estimate hybrid maize seed production loss associated with manual detasseling and the impact that new genetic technology can have on improving and simplifying hybrid maize production. The detasseling process is estimated to reduce hybrid maize seed production by 14.0%, representing a significant yield and associated economic loss to seed companies. This is the equivalent of an additional 0.70 or 0.98 t ha−1 in maize seed production fields at an average potential seed yield of 5 or 7 t ha−1, respectively. The economic benefit of this additional hybrid maize seed production will vary by seed company and the conditions under which production occurs within a country. Most maize hybrids on the market in SSA are three-way hybrids; thus, this loss will be compounded with the two hybridization steps required to produce three-way hybrids. The use of a nuclear genetic male sterility-based hybridization platform that bypasses the need for manual detasseling in both hybridization steps would offer a significant seed yield benefit to seed companies. An additional economic benefit not captured in this study is the possible loss associated with contaminating pollen shed within a seed production field if manual detasseling is not perfect.

Over the past two decades there has been an influx of new companies entering the hybrid maize seed business space in SSA, especially in ESA25,26,27. However, many of the new seed companies lack expertise and experience in maize hybrid seed production. This has been one of the major challenges both in terms of obtaining economic seed yields and achieving the required genetic purity standards of certified seed. Contaminating pollen shed within a seed production field warrants discarding a large area around any female parent shedding pollen or even condemning entire field. In one commercial seed production site that was visited as part of this study, most female parent plants had started to shed pollen, and the entire production field was condemned. The two hybridization steps in conventional three-way hybrid production increases the probability of contaminating pollen shed occurring.

Hybrids developed using Ms44 segregate 50:50 for PP and NPP plants and are classified as 50% non-pollen producing (FNP). FNP hybrids have been shown to have a yield advantage to farmers under low input conditions, providing an additional benefit to smallholder farmers18. FNP hybrids have previously been shown to have a higher kernel number18,28,29, 100-kernel weight18,30, and kernel length30 relative to PP hybrids. Both detasseling and NPP reduce apical dominance and enhance biomass partitioning to the ear. However, most pollen grains are already formed if the tassel is removed just before anthesis31,32. One of the differences between detasseled plants and Ms44 male-sterile plants is that the pollen does not fully form in Ms44 male-sterile plants, likely reducing the demand for photosynthate to produce starch-filled pollen grains; this may be one of the reasons for improved yield. Detasseling does increase light interception, although the benefits of this are a function of the tassel size. Unlike temperate maize which has undergone intensive indirect selection for reducing tassel size, in tropical maize, in general, this trait has not changed. The potential positive effect on grain yield that may result from the removal of tassels only in the PP entries was not determined in this study.

Detasseling is undertaken before the tassel protrudes to avoid contaminating pollen shed. Only 3.9% of tassels collected in seed production fields had no attached leaves confirming this is relatively rare. There were no significant differences in the number of kernels produced by NPP and PP plants, except for the smallest class which accounted for less than 3.0% of kernels. Seed sizing was only conducted in the trial with one leaf removed. It is possible that when a greater number of leaves were removed the proportion of each seed class changes; however, similar results were observed during the use of SPT with ms45. No significant differences in seed sizing between hybrids produced with ms45 SPT relative to hybrids produced with detasseling were identified (Marc Albertsen, personal communication).

The use of CMS, which also mitigates the need to detassel the female parent plant in hybrid maize seed production, would likely provide a similar seed yield benefit to the private sector23. The inherent disadvantage in identifying a second non-restoring male parent required in using CMS in three-way hybrid production not only limits its use in three-way hybrid production, but also can limit the choice of germplasm diversity to produce the most heterotic combinations possible. Furthermore, a CMS-derived hybrid blended with a conventionally derived hybrid does not consistently provide a yield benefit to farmers, unlike Ms44 derived hybrids.

Mechanical detasseling largely bypasses the need for contract labour, but it can result in greater damage to the top leaves33. Despite varying levels of experience and training across the commercial seed production fields and the different three-way hybrids being produced in this study, the distribution of leaves removed with the tassel during the manual detasseling process was relatively similar across locations. Theoretically, seed yield loss could be lowered by reducing the number of leaves removed during the detasseling process; however, this increases the potential for self-pollination and risks higher economic losses to seed companies due to the failure of the production field to meet certification standards. Labour is increasingly a limiting factor in agriculture in SSA34,35,36. Competing demands for contract labour, primarily due to tobacco production and artisanal gold panning, were found in this study to be a major constraint faced across commercial seed production fields in South Africa and Kenya. Competing demands for labour with a tobacco farm were responsible for an entire maize seed production field being condemned in this study. In a second maize seed production field, labour was only available at the weekend due to competing labour demands within tobacco production.

Despite the plethora of studies highlighting the potential benefit of single gene technologies to increase crop yields, there are significantly less studies confirming their impact within a target environment37. The yield benefit provided by FNP hybrids was the first example of a single gene technology conferring a significant yield advantage in smallholder farmers’ fields in SSA18. The results of this study provide confirmation of a second benefit of this single gene, by mitigating the significant seed yield loss associated with the detasseling process in seed production, and at the same time simplifying seed production for seed producers.

Conclusions

The use of the Ms44-SPT sterility-based hybridization platform in hybrid maize seed production would increase seed production yields by 14.0%, whilst also improving the genetic purity and quality of the final hybrid. In the production of three-way maize hybrid seed, this benefit would be realised in both hybridization steps, although the benefit during single-cross female production has not been quantified. The availability of new female lines converted with Ms44-SPT would offer significant economic benefit to seed companies and may provide an inflection point in the innovation pathway of climate-resilient maize hybrids in SSA.

Material and methods

Effect of leaf removal on hybrid maize seed production

A total of 18 single-cross female maize hybrids were used in this study. The source of maize seeds was the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT). Nine of the single-cross female hybrids were produced using female lines converted with Ms44-SPT and thus were non-pollen producing (NPP) and did not require detasseling for three-way hybrid seed production. The remaining nine single-cross females were produced using the same female lines that had not been converted with Ms44-SPT. They were, therefore, pollen-producing (PP) and required detasseling for three-way hybrid seed production. Due to limited seed availability, the number of pairs of single-cross females varied across trials. The number of entries for each experiment are listed in (Table 2).

Two different trials were conducted during 2021–2022 to quantify the effect of tassel and leaf removal during the detasseling process in hybrid maize seed production (Table 2). In the first trial, at tassel emergence but before pollen shed, the tassel and one or three leaves nearest to the tassel were removed from PP single-cross females. One leaf removal was conducted at a total of 20 locations, with one or three leaf removal at seven locations. These locations were planted with four-row plots. One leaf was removed from two rows, and three leaves were removed from the other two rows (rows were adjacent but assigned randomly). Because the tassel in NPP single-cross females did not produce pollen, it was not removed. Similarly, no leaves were removed from NPP single-cross females. These trials were conducted at nine locations in South Africa and 18 locations in Kenya.

The first year of trials were run concurrently with the sampling to determine the actual number of leaves removed in commercial maize seed production fields during the detasseling process. This highlighted the need to establish seed yield loss associated with the removal of more than three leaves. In 2022 a second trial with five treatments was conducted at four locations in Kenya with eight entries. Upon tassel emergence but before pollen shed, the tassel along with one, two, three, four or five top leaves (nearest the tassel) were removed from PP single-cross females. Each treatment was in a two-row plot, and plots were nested by hybrid. In NPP single-cross females, neither the tassel nor any top leaves were removed.

All trials were irrigated, and optimum agronomic management was followed. Plots were 3 m long with 0.75 m between rows and 0.25 m within row spacing in two or three replications (Table 2). Surrounding each nest and trial were blends of male pollinator planted in adequate rows to ensure adequate pollen for the duration of silking. For locations with one leaf or one and three leaves removed, the pollen producing (PP) and non-pollen producing (NPP) single-crosses were nested side by side. For the second trial with one to five leaves removed, pedigrees were nested together and the six treatments randomly assigned to plots within the nest.

At physiological maturity, all plants in two rows per replication per entry were hand harvested, with seed weight and moisture content measured. Seed weight was adjusted to 13.5% moisture content. From 18 locations in Kenya where one top leaf had been removed (from both Trial 1 and Trial 2), a 1 kg seed sample was randomly sub-sampled from each plot for seed grading. Seed was graded by kernel width and length by passing the seed through a series of screens. Firstly, seeds were separated into width classes using round hole screens. Seed was passed successively through large (11.0 mm), medium (9.5 mm) and small (6.5 mm) screens to separate seed. Seed from each width class was separated by passing the samples though slotted screens. Seed that failed to pass through a 6.5 mm slotted screen was classified as round. Seed that passed through the 6.5 mm screen but failed to pass through a 5.5 mm slotted screen was classified as thick seed. Seed that passed through the 5.5 mm slotted screen was classified as flat. The number of seeds in each of the six classes was counted. For each class, two samples of 100 kernels each were taken, and 100-kernel weight was estimated. For the large flat and large round seed classes, the majority of plots had less than 100 kernels; thus, the data from these two classes was excluded from subsequent analysis.

Establishing number of leaves removed during detasseling in commercial seed production fields

The number of leaves removed during detasseling was measured at three seed companies in both South Africa and Zimbabwe. In each three-way hybrid maize seed production field, detasseling teams were employed as contracted labour by seed companies. The level of training and experience varied within each team. After the detasseling teams removed the tassels from the female parent plants, 2000 tassels were collected. The detasseling teams were not informed in advance to avoid any possible bias. Tassels were transported back to the field stations and the number of top leaves attached to the tassel were counted.

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.2.2.). Yield data were analysed using linear mixed-effects modelling. The two trials were analysed separately and combined. The number of top leaves removed was treated as a continuous fixed effect to estimate the yield reduction per-leaf removed. The random effect’s structure was kept as maximal as the experimental design allowed. Each model contained a random intercept for location-year (the combination of year and location), a pedigree replicate within a location-year, and a random slope and intercept for each pedigree in a location-year. The overall effect of leaf removal on yield was then quantified by computing the (restricted) maximum likelihood (REML) estimate of the coefficient associated with number of leaves removed.

Seed grade data were analysed using logistic mixed-effects regression for kernel counts and linear mixed effects regression for kernel weight, with a fixed effect factor indicating whether seed was pollen or non-pollen producing and a random intercept for location-year, a pedigree replicate within a location-year, and for each pedigree in a location-year. Independent models were fit for each grade. The p-values were adjusted using Holm-Sidak.

Model fitting

The fit of the joint data to the model is evaluated by checking several model assumptions including linearity of yield with respect to leaf removal, homogeneity of variance, normality of residuals, and normality of random effects (Supplementary Fig. 1). There was no egregious deviation from the assumption of linearity and homogeneity of variance. Using the Cook’s distance and a threshold of 0.7, 93 outliers were identified. After examining each data entry, none were found to be because of data entry error or due to any systematic error so none of the entries were excluded from the analysis. However, the residuals did not appear normally distributed, implying that standard inferences and p-values would be uncertain, thus a fully nonparametric bootstrap method was used to obtain p-values and confidence intervals38. The resampling in the bootstrap is done at the two lowest level clusters: replicates and observations using 1000 bootstrap samples.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study and the code for all statistical analysis and figures are available on CIMMYT Dataverse (https://hdl.handle.net/11529/10549126).

References

Boyer, J. S. et al. The U.S. drought of 2012 in perspective: A call to action. Glob. Food Sec. 2, 139–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2013.08.002 (2013).

Atlin, G. N., Cairns, J. E. & Das, B. Rapid breeding and varietal replacement are critical to adaption of developing-world cropping systems to climate change. Glob. Food Sec. 12, 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2017.01.008 (2017).

Setimela, P. et al. When the going gets tough: performance of stress tolerant maize under conservation agriculture during the 2015/16 El Nino season in southern Africa. Agric. Water Manag. 268, 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2018.09.006 (2018).

Katengeza, S. P. & Holden, S. T. Productivity impact of drought tolerant maize varieties under rainfall stress in Malawi: A continuous treatment approach. Agric. Econ. 52, 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12612 (2021).

Jain, M., Barrett, C. B., Solomon, D. & Ghezzi-Kopel, K. Surveying the evidence on sustainable intensification strategies for smallholder agricultural systems. Ann. Rev. Environ. Res. 48, 347–369. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-112320-093911 (2023).

Cairns, J. E. et al. Challenges for sustainable maize production in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Cereal Sci. 101, 103274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2021.103274 (2021).

Cairns, J. E. & Prasanna, B. M. Developing and deploying climate-resilient maize varieties in the developing world. Curr. Op. Plant Bio. 45, 226–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2018.05.004 (2018).

Chivasa, W. et al. Maize varietal replacement in Eastern and Southern Africa: Bottlenecks, drivers and strategies for improvement. Glob. Food Sec. 32, 100589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100589 (2022).

Brennan, J. P. & Byerlee, D. The rate of crop varietal replacement on farms: measures and empirical results for wheat. Plant Var. Seed. 4, 99–106 (1991).

CGIAR Research Program on Maize. Maize Agrifood Systems Proposal 2017–2020 (CIMMYT, 2016).

Donovan, J., Rutsaert, P., Spielman, D., Shikuku, K. M. & Demont, M. Seed value chain development in the global South: Key issues and new directions for public breeding programs. Outlook Agric. 50, 366–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/00307270211059551 (2021).

Spielman, D. J. & Smale, M. Policy Options to Accelerate Variety Change among Smallholder Farmers South Asia and Africa South of the Sahara (IFPRI Discussion Paper 01666, 2017).

Magnier, A., Kalaitzandonakes, N. & Miller, D. J. Product life cycles and innovation in the US corn industry. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 13, 17–36. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.93557 (2010).

Jaleta, M., Hodson, D., Abeyo, B., Yirga, C. & Erenstein, O. Smallholders’ coping mechanisms with wheat rust epidemics: Lessons from Ethiopia. PLoS One 14, e0219327. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219327 (2019).

Prasanna, B. et al. Maize lethal necrosis (MLN): Efforts toward containing the spread and impact of a devastating transboundary disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Virus Res. 282, 197943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2020.197943 (2020).

Schut, M. et al. Innovation platforms: experiences with their institutional embedding in agricultural research for development. Exp. Agric. 52, 537–561. https://doi.org/10.1017/S001447971500023X (2016).

Barrett, S. & Chaitanya, R. S. K. Getting private investment in adaptation to work: Effective adaptation, value, and cash flows. Glob. Environ. Change 83, 102761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2023.102761 (2023).

Collinson, S. et al. Incorporating male sterility increases hybrid maize yield in low input African farming systems. Comm. Biol. 5, 729. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03680-7 (2022).

Wilhelm, W. W., Johnson, B. E. & Scheper, J. S. Yield, quality, and nitrogen use of inbred corn with varying numbers of leaves removed during detasseling. Crop Sci. 35, 209–212 (1995).

Levings, G. S. The texas cytoplasm of maize: Cytoplasmic male sterility and disease susceptibility. Science 250, 4983 (1990).

Weider, C. et al. Stability of cytoplasmic male sterility in maize under different environmental conditions. Crop Sci. 49, 77–84. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2007.12.0694 (2009).

Gaffney, J. et al. Robust seed systems, emerging technologies and hybrid crops for Africa. Glob. Food Sec. 9, 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2016.06.001 (2016).

Kim, Y. J. & Zhang, D. Molecular control of male fertility for crop hybrid breeding. Trend Plant Sci. 23, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2017.10.001 (2018).

Wu, Y. et al. Development of a novel recessive genetic male sterility system for hybrid seed production in maize and other cross-pollinating crops. Plant Biotech. J. 14, 1046–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.12477 (2016).

Langyintuo, A. S. et al. Challenges of the maize seed industry in Eastern and Southern Africa: A compelling case for private–public Intervention to promote growth. Food Pol. 35, 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.01.005 (2010).

AGRA. Seeding an African Green Revolution: The PASS Journey. Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa https://agra.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/PASS-Book-web.pdf (2017).

Bonny, S. Corporate concentration and technological change in the global seed industry. Sustainability 9, 1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091632 (2017).

Fox, T. et al. A single point mutation in Ms44 results in dominant male sterility and improves nitrogen use efficiency in maize. Plant Biotech. J. 15, 942–952. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.12689 (2017).

Loussaert, D. et al. Genetic male sterility (Ms44) increases maize grain yield. Crop Sci. 57, 2718–2728. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2016.08.0654 (2017).

Hamadziripi, E. et al. Validating a novel genetic technology under management practices associated with resource-constrained farmers: Assessing the impact of recycling 50% non-pollen producing hybrid maize seed on yields in Zimbabwe. Plant People Planet https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.10590 (2024).

Horner, H. T. & Palmer, R. G. Mechanisms of genic male sterility. Crop Sci. 35, 1527–1535. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1995.0011183X003500060002x (1995).

Uribelarrea, M., Cárcova, J., Borrás, L. & Otegui, M. E. Enhanced kernel set promoted by synchronous pollination determines a tradeoff between kernel number and kernel weight in temperate maize hybrids. Field Crop Res. 105, 172–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2007.09.002 (2008).

Nicoletti, M. A., Ortiz, T. A. & Takahashi, L. S. A. Yield and physiological quality of corn seeds after application of detasseling techniques in two cropping seasons. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 17, 69–73. https://doi.org/10.21475/ajcs.23.17.01.p3788 (2023).

Yeboah, F. K. & Jayne, T. S. Africa’s evolving employment trends. J. Dev. Stud. 54, 803–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1430767 (2018).

Baudron, F. et al. A farm-level assessment of labor and mechanization in Eastern and Southern Africa. Agron. Sust. Dev. 39, 17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-019-0563-5 (2019).

Silva, J. V., Baudron, F., Reidsma, P. & Giller, K. E. Is labour a major determinant of yield gaps in sub-Saharan Africa? A study of cereal-based production systems in Southern Ethiopia. Agric. Sys. 174, 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2019.04.009 (2019).

Khaipho-Burch, M. et al. Genetic modification can improve crop yields-but stop overselling it. Nature 621, 470–473. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02895-w (2023).

Van der Leeden, R., Meijer, E. & Busing, F. M. Resampling multilevel models. In Handbook of Multilevel Analysis (eds Van der Leeden, R. & Meijer, E.) (Springer, 2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation project Seed Production Technology for Africa (Grant Number OPP1137722 and INV-018951) and the CGIAR Accelerated Breeding Initiative. Under the grant conditions of the Foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the Author Accepted Manuscript version that might arise from this submission. We gratefully acknowledge the support of seed companies in South Africa and Zimbabwe for providing access to their seed production fields and the seed companies in Kenya and South Africa for hosting trials. We also acknowledge the support of Boniface Nyamande and Esnath Tatenda Hamadziripi for their help in conducting fieldwork in Zimbabwe, the KALRO and ARC field technicians for their support in conducting field trials in Kenya and South Africa, and Andy Watt and Qualibasic Seed staff for their support in seed sizing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was conceptualised by SC, MA and MSO. LN, DL, WC, KM, BTE and JEC led the field work. SC, BD and JEC undertook the data analysis. JEC and SC wrote the manuscript. BMP and MSO led funding acquisition. LN, BD, DL, MA, WC, KM, MSO, BTE and BMP revised, proofread and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no known competing interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. SC, BD and MA are employees of Corteva Agriscience. Corteva Agriscience owns the rights to the technology. There are no competing interests as Corteva Agriscience is providing the technology royalty-free to licensed seed companies producing seed for smallholders in the region under the terms of the Seed Production Technology for Africa agreement (https://www.cimmyt.org/content/uploads/2019/03/CIMMYT-SPTA-project-brief-2020-07-web.pdf). MSO is currently an employee of Bayer but was an employee of CIMMYT during this study and declares no potential conflict of interest. JEC, LN, DL, WC, KM, BE and BMP declare no potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Collinson, S., Cairns, J.E., Ndlala, L. et al. Ms44-SPT: unique genetic technology simplifies and improves hybrid maize seed production in sub-Saharan Africa. Sci Rep 14, 32125 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83931-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83931-1