Abstract

The research investigated the challenges of agricultural sustainable development in Haryana by employing the Sustainable Livelihood Security Index (SLSI) as a comprehensive evaluative tool. The study integrates economic efficiency, ecological security and social equity dimensions through selected indicators and by utilizing Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to eliminate spatial variations among districts. The Economic Efficiency Index (EEI) reveals distinct agricultural performances with Karnal excelling in food production and Panchkula demonstrating efficient fertilizer use. The Ecological Security Index (ESI) highlights Gurgaon’s significant land use practices and Panchkula’s determinantal to forest conservation. The Social Equity Index (SEI) advancements in female literacy and healthcare. Integrating these three indices showed that Panchkula emerges as a paragon of overall sustainability, followed closely by Karnal, Sirsa and Gurgaon. Disparities in Nuh and Faridabad addressed the necessity for targeted interventions. These study findings offered to the policymakers about the crucial insights into district-specific needs which guiding them in the formulation of strategies for inclusive growth and sustainable development for each district’s unique challenges and opportunities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sustainable development goals can only be achieved by improving regional sustainability which is particularly relevant for developing countries like India. The origin of the concept of ‘sustainable development (SD)’ achieved global prominence in the late 1980s, with the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) report ‘Our Common Future’ i.e., the concept of sustainable development is defined as “development that caters to current needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own requirements”1. In the context of India, research on sustainability and their dimensions has emerged gradually over the past decade with studies addressing sustainable forest management, methodologies for sustainability assessment, and various dimensions of sustainable agriculture2,3,4. India’s agricultural sector holds a pivotal position in ensuring food and nutritional security, sustainable development, and poverty alleviation, having made significant strides in food grain production since the Green Revolution. However, challenges such as shrinking land holdings, shifts to non-profitable commercial crops, mounting debts, and vulnerability to market forces have surfaced, contributing to a decline in agricultural output and adverse ecological impacts5. The advancement of the SD concept has prompted the initiation of diverse environmental reforms globally over the past few decades6. The interrelated dimensions of SD, namely ecological, economic, and social, are integral to its holistic application7. The ecological dimension underscores a society’s resilience in the face of disturbances and stresses, prioritizing the maintenance of a stable resource base and the cautious use of non-renewable resources8. Similarly, the economic aspect emphasizes the continuous production of goods and services to prevent detrimental sectoral imbalances, while the social dimension aims for equitable distribution, access to social services, gender parity, and political accountability9.

The precise quantification of sustainability proves challenging due to its site-specific and dynamic nature10. Nonetheless, when specific parameters are selected, trends can be discerned, indicating stability, improvement, or decline11. The measurement of sustainability often involves evaluating changes in yields and total factor productivity, particularly in the context of agricultural practices12. Significant sustainability indicators which include pesticide use, inorganic fertilizer use and biodiversity advancement13. There is an abundance of approaches that have been developed to evaluate the sustainability of livelihoods at both the micro and macro levels.

Regional sustainability is influenced by three important factors i.e., economic, environmental, and social dimensions with that the concept of Sustainable Livelihood Security Index (SLSI), emerged and proposed by Swaminathan7 that serves as an evaluative tool for comprehending and implementing SD. Sustainable livelihood security (SLS) is defined as the assurance of ecologically sound, economically efficient, and socially equitable livelihood options14. The intricate linkages between SLS and overarching welfare objectives such as poverty reduction and human development underscore the significance of SLSI for the sustainable development of agriculture (SDA)4. Consequently, the three-dimensional framework of SDA necessitates the integration of SLSI, comprising ecological security index (ESI), economic efficiency index (EEI), and social equity index (SEI) to discern the interplay and conflicts among the ecological, economic, and equity facets of SDA15. SLSI serves as a pragmatic and easily comprehensible instrument for evaluating sustainability, aiding in the formulation of policies and strategies for enhancing the security of rural livelihoods through the implementation of vital income-generating strategies and the enhancement of knowledge. It offers a unidimensional metric to assess country-specific information on multifaceted aspects of sustainable development, including economic, environmental, and social conditions16. This index is instrumental in realigning development programs and prioritizing development investments in highly susceptible areas.

Hickel17 proposed a sustainable development index as a ratio of a development index to an ecological impact index, underscoring the complex interplay between development and environmental degradation. This study initially incorporated a diverse set of 20 indicators, primarily drawn from agricultural sustainability frameworks, alongside select parameters addressing the United Nations’ SDGs. While various frameworks and models have previously been proposed for measuring agricultural sustainability, the complexity of the concept and the lack of consensus among researchers regarding its dimensions and indicators have posed challenges. Earlier delineations of the regions under consideration were based on soil, climate, physiography, effective rainfall, and soil groups. However, these classifications exhibit certain limitations in policy planning, thereby affecting the development of these districts. To date, no recent sustainability assessment has been conducted in this Northern region of India especially in Haryana based on economic, social, and ecological indicators. Given the significant influence of these indicators on the achievement of sustainable development goals, this research was conducted. Thus, Sustainable Livelihood Security Index (SLSI) is poised to aid in this process by providing comprehensive district-level information on economic, social, and environmental parameters, thereby facilitating informed decision-making and effective implementation strategies for inclusive growth, sustainable development, and the mitigation of inter-district imbalances. This paper endeavors to compute the district-wise SLSI for the state of Haryana, India, with the aim of providing valuable insights to planners and policymakers.

Materials and methods

Study area

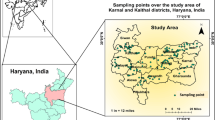

The state of Haryana, positioned between latitudes 27° 39’ and 30° 55’ N and longitudes 74° 28’ and 77° 36’ E, covers an expanse of approximately 4.4 million hectares, constituting about 1.3 per cent of the country’s total geographical area (TGA). With 22 administrative districts (Fig. 1) further divided into 126 tehsils, Haryana’s landscape exhibits three key physiographic divisions: the Shivalik Hills, the Semi-Arid Plain, and the Flood Plains of the Yamuna River. These divisions manifest distinct characteristics, giving rise to the Northern Shivalik Region, Southern Haryana, and Yamuna-Ghaggar Plain, respectively. The regional climate showcases a range from semi-arid to sub-humid, featuring discernible variations between hot summers and cold winters. Haryana experiences an average annual rainfall spanning 320 to 800 millimeters, with temperature fluctuations between 10 °C and 45 °C throughout the year. Noteworthy agricultural practices in the state primarily center around the cultivation of staple crops, including wheat, rice, sugarcane, coarse cereals, and pulses, with a notable dependency on rainfed irrigation for a significant portion of agricultural endeavors. Agriculture, serving as the linchpin of Haryana’s economic and developmental ambitions, engages a substantial segment of the state’s populace, with a notable reliance on seasonal precipitation for sustenance. However, the insufficient vegetative cover and alarming deforestation rates in select regions contribute significantly to soil erosion and consequent reservoir siltation, leading to considerable degradation of water quality and disruption of the ecological equilibrium.

(Source for the map: https://haryanacmoffice.gov.in/haryana-map. The map has been modified using appropriate tools and is not based on any copyrighted source).

Schematic representation of study area in map (Haryana state).

Selection of indicators

The process of choosing appropriate indicators to effectively represent the conditions of each dimension can be extensively discussed18. The selection of these indicators was informed by existing literature, prioritizing factors that are relevant, analytically sound, measurable, adaptable to various scales (such as farm, district, or country), and sensitive to both ecosystem processes and the influence of management practices and climate variations. While the rationale behind the inclusion of these indicators is clear, we acknowledge the need for a more detailed justification of both the inclusion and exclusion processes. In terms of inclusion, we prioritized indicators that provides more as comprehensive perspective on agricultural sustainability. For instance, economic efficiency indicators, such as crop yield, farm income, and resource use efficiency has selected to assess the financial sustainability of farming systems. Ecological indicators which include soil health and water use efficiency has incorporated to reflect the environmental sustainability of agriculture. Social equity indicators such as access to healthcare, education and social welfare, were included to capture the social dimension of sustainability. Regarding the exclusion of specific indicators that practical constraints such as data availability and relevance to the specific context of Haryana have carefully considered. Some indicators have significant in global sustainability discussions were excluded due to limited data availability or their less direct impact on the local sustainability challenges faced in Haryana. For example, indicators related to global trade and market access were not included as they were considered to have a less direct influence on local agricultural sustainability in the study region. The proposed indicators align with established suitability criteria, encompassing dimensions of social and policy relevance, analytical robustness, scalability, consideration of ecosystem processes, and responsiveness to variations in management and climate conditions19. These indicators were systematically categorized to align with the Sustainable Livelihood Security (SLS) framework across all 22 districts of the state. A comprehensive overview of the selected variables and their corresponding units of measurement has been described in Table 1.

Collection of data and its sources

The study based on secondary data from various government reports, including the State of Forest Report (Forest Survey of India), Dynamics of Groundwater Resources of India (Central Ground Water Board), and reports on the area, production, productivity, and prices of agricultural crops in Haryana. Data was also sourced from the Statistical Abstract of Haryana and final estimates of area, production, and average yield of principal crops in Haryana (Directorate of Economics and Statistics).

Principal component analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA), an enduring multivariate technique pioneered by Pearson20 and further developed by Hotelling21 served as a valuable tool for comprehending the spatial disparities at the district level, encompassing multiple interconnected multidimensional variables. Its selection is rooted in two fundamental objectives: firstly, the reduction of data dimensionality, and secondly, the interpretation of data in terms of principal components. PCA accomplishes this through the transformation of the initial variables into a fresh array of variables referred to as principal components. These principal components, which are uncorrelated, are systematically organized to ensure that the primary component encapsulates the utmost variability across all the original variables. Its utility extends to various domains, including spatial and longitudinal analyses22. Before initiating the PCA, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) assessment is administered to evaluate the adequacy of the sample for the different indicators. The KMO statistics assess the strength of the associations among the variables, with values ranging from 0 to 1. A KMO value equal to or exceeding 0.600 signifies the suitability of the data for PCA, while values below the threshold are deemed inappropriate for the analysis23.

Evaluation of index values

Given that indicators are subject to measurement in diverse units and scales, we applied normalization24 for the purpose of standardizing the indicators. This normalization process was carried out to render the figures unit-free and to ensure uniformity in their values, thereby constraining them to a standardized range of 0 to 1. Before embarking on this normalization process, it becomes imperative to discern the functional association between the indicators and the concept of sustainability. Such a relationship can assume two forms: (a) a positive relation wherein sustainability enhances as the indicator value rises, or (b) a negative correlation wherein sustainability diminishes as the indicator value increases.

To organize the collected data for each sustainability dimension, a structured rectangular matrix was formulated, where rows denoted the districts and columns symbolized the respective indicators. Considering the existence of L districts (j = 1, 2, …, L) and the collection of K indicators (i = 1, 2, …, K), the resulting table comprised L rows and K columns. Represented as xij, the value of the ith indicator pertaining to the jth district was delineated.

where Min{xij}and Max{xij} are the minimum and maximum value of ith indicator among all the L districts respectively.

where \(\sum\:_{\text{1}}^{\text{i}}{\text{w}}_{\text{i}}\text{=1}\) where ESIj represents the ESI for jth district and wi denotes the weight associated with the ith indicator included for computation of ESI.

For estimating the weight25 associated with the indicator

where C is a standardized constant such that

Adopting this approach for selecting the weights guarantees that an extensive variation in any single indicator would not excessively overshadow the impact of the other indicators, thereby preventing any distortion in the inter-district evaluations. Similar to the calculation of ESIj, the values for EEIj (EEI) and SEIj (SEI) were determined. Consequently, the sustainability indices (ESI, EEI, and SEI) evaluated within the range of 0 to 1, with 1 denoting optimal sustainability and 0 indicating a lack of sustainability within the ecosystem.

Therefore, Sustainable Livelihood Security Index (SLSI) was computed as follows.

Results and discussion

PCA factor loading of associated variables and their relevance

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) results has used to reduce dimensionality and identify the key factors influencing the farm sustainability indices across the districts of Haryana The factor loadings of associated 28 indicators for the SLSI are provided in Table 2. The first five principal components explain 77.921% of the overall variance of the original data set, of which the first two components take a significant share of 51.094%. The eigenvalues, percentage variability, and cumulative variance of each PC are elicited and the amount of variability accounted for by PCA in terms of PC1, PC2, PC3, PC4, and PC5 was 34.067%, 17.027%, 10.772%, 9.100%, and 6.955%, respectively. Seven variables were found to be high association from PC 1 i.e., fertilizer consumption (0.933), average size of land holdings (0.916), net sown area (0.865), capacity of state-owned warehouses (0.838), total cropped area (0.901), road length (0.864) and groundwater availability (0.851) and contributed maximum variability (34.067%). PC2 for five variables i.e., population served per bank (-0.575), per capita income at current price (0.747), population density (0.694), employees of organized sectors (0.573) and incidences of IPC crime (0.922). PC3 is primarily associated with population served per bank (0.660), deviation of annual rainfall (-0.589), groundwater resource (-0.607) and teacher pupil ratio in primary (0.655). The fourth principal component (PC4) is associated with annual rainfall (0.731), livestock density (-0.645) and total forest area (0.755). Similarly, PC5 shows higher associated with productivity of food grains (0.463), groundwater development stress (0.460) and teacher pupil ratio in primary (0.423).

PC1 has predominantly been driven by economic efficiency indicators, such as crop yield, farm income and resource utilization. It reflects the financial viability and resource optimization of agricultural systems. In practical terms, districts with high scores on PC1, like Sirsa and Karnal, exhibit better economic sustainability in agricultural practices. These districts demonstrate robust agricultural productivity and resource efficiency, which are crucial for ensuring the long-term sustainability of farm households. Whereas PC2 captured aspects related to ecological security, influenced by indicators such as soil health, water usage efficiency, and overall environmental management. It reflects the ecological resilience of farming systems, which is necessary for maintaining productivity while minimizing adverse environmental impacts. Districts with high scores on PC2, such as Hisar and Fatehabad, perform better in terms of ecological stewardship. These areas are characterized by sustainable agricultural practices that prioritize environmental conservation, highlighting the need for policies focused on preserving natural resources for future generations. PC3 focused on social equity, with indicators such as access to education, healthcare, sanitation, and overall quality of life for farm households. A higher score on PC3 indicates that a district performs well in terms of social inclusion and the equitable distribution of resources, ensuring that the benefits of agricultural growth are shared across all sections of society. Karnal, for example, scores highly on PC3, pointing to its strong social welfare systems and equitable access to essential services. This reflects the importance of addressing social equity in promoting sustainable livelihoods for farming communities. The cumulative contribution of these three-component economic efficiency, ecological security, and social equity provides a holistic view of sustainability in Haryana’s agriculture. The PCA results reveal that economic efficiency and ecological security are the dominant drivers of farm sustainability in most districts, but social equity plays a significant role, especially in districts like Karnal, where social programs support inclusive growth. By considering the practical implications of these components, we can better understand how different districts can improve their sustainability outcomes and address specific challenges related to economic, ecological, and social dimensions of agricultural development.

Economic efficiency index (EEI)

The data presented in Table 3 provides the overall economic efficiency which has evaluated across several dimensions, such as food grain productivity, fertilizer and pesticide consumption, average farm size, net sown area, milk yield, banking services, per capita income, annual rainfall, and warehouse capacity. These diverse indicators contribute to an overall understanding of the economic performance of the region. Karnal (1.000) stands out for its exceptional performance in food grain productivity which reflecting its strong agricultural stability. Panchkula (1.000) excels in fertilizer consumption which indicating the efficient resource use. Similarity, Sirsa (1.000) demonstrates the highest pesticide consumption which may suggest challenges in pest management that could require attention to more sustainable practices. The average farm size also varies significantly among districts. Larger land holdings are observed in districts like Karnal (0.729) and Sirsa (1.000) that suggesting more favorable conditions for large-scale farming, while districts such as Charkhi Dadri (0.161) and Faridabad (0.097) report smaller average farm sizes, possibly due to different agricultural practices or land constraints. Gurgaon (1.000) emerged as a leader, indicating efficient land use practices in the context of net sown area, benefits from a high per capita income showing its economic prosperity. Meanwhile, Panchkula highlighted strong performance in milk yield (0.953) and the capacity of state-owned warehouses (1.000) exhibiting its diverse agricultural strengths and storage infrastructure. When aggregating all these indicators into the Economic Efficiency Index (EEI), a clearer picture of each district’s overall economic health calculated. Districts like Karnal (0.511), Kurukshetra 0.532) and Panchkula (0.528) are among the top performers, reflecting balanced and significant economic performance across various indicators. While, districts such as Charkhi Dadri (0.368), Mahendragarh (0.393) and Palwal (0.260) exhibited lower values indicating to areas where targeted interventions could drive improvement.

Ecological security index (ESI)

A district-wise evaluation of Ecological Security (Table 4) by examining various indicators that reflect the ecological balance and sustainability of agricultural practices in each district. Each district’s ecological security has measured using indicators such as cropping intensity, population and livestock density, forest cover, total cropped area, deviation of annual rainfall, groundwater development stress, and groundwater resources. Panchkula (1.000) emerges as a leading district in terms of ecological security particularly excelling in livestock density and forest cover. These strong ecological factors contribute to Panchkula’s overall ESI value of 0.631 securing it as one of the more environmentally sustainable districts. Sirsa also performs well achieving top scores in population density (1.000) and total cropped area (1.000), leading to a high ESI of 0.641 although has groundwater development stress (0.483) indicates potential pressure on water resources. Similarly, Faridabad secured the lowest in ecological security with several key indicators such as cropping intensity (0.000), livestock density (0.000), and total forest area (0.113) revealing significant ecological challenges that makes the worse value of ESI (0.233) which suggesting a need for focused ecological interventions, particularly in enhancing forest cover and reducing stress on groundwater resources.

The ESI values for other districts such as Bhiwani (0.629) and Fatehabad (0.588) showed relatively balanced ecological performance. Bhiwani’s high population density (0.982) and groundwater development stress (0.681) while Fatehabad’s strong deviation in annual rainfall (0.776) and cropping intensity (0.673) suggest agricultural resilience. However, both districts will need to address certain ecological vulnerabilities to ensure long-term sustainability. Mahendragarh (0.598) has primarily driven by its high groundwater resource score (1.000), which is a significant ecological advantage. However, the district’s low forest area (0.065) and relatively high population density (0.915) pose ecological concerns that could affect the overall environmental balance. In the contrast, Gurgaon has strong performance in rainfall deviation (0.954) and groundwater resource availability (0.594). Despite these strengths, the district’s relatively low total cropped area (0.097) and population density (0.579) limit its overall ecological security, reflected in an ESI of 0.522. Also districts such as Faridabad (0.233) and Palwal (0.477) with low ESI scored highlighted the need for urgent ecological interventions, particularly in the areas of forest regeneration and groundwater management.

Social equity index (SEI)

Table 5 provides a detailed analysis of Social Equity across various districts evaluating on factors such as female literacy, infant mortality, road infrastructure, access to agricultural electricity connections, credit societies, employment in organized sectors, school availability, crime incidences, groundwater availability, and teacher-pupil ratios. Karnal (0.745) stands out with the highest Social Equity Index by excelling in significant sectors such as agricultural electricity connections (1.000), access to primary agricultural credit societies (1.000), teacher-pupil ratios (0.741) and also performing well in terms of female literacy (0.687) and government-recognized schools (0.727) has reflected its strong social infrastructure and commitment to equity in education and agriculture. Similarly, Hisar (0.626) achieves a second highest SEI by its exceptional road length (1.000) and strong presence in organized sector employment (1.000) which contributing to its overall social stability and infrastructure development. Jind’s notable achievements include a perfect score in groundwater availability (1.000), alongside significant progress in road infrastructure (0.565) and female literacy (0.478). Sirsa excels in both road length (0.889) and groundwater availability (0.646), reflecting a balanced approach to social development and infrastructure. Therefore, these districts i.e., Jind (0.627) and Sirsa (0.666) also demonstrate strong performance in social equity. Similarly, districts such as Faridabad (0.309) and Charkhi Dadri (0.351) showed significant challenges in terms of social equity. Faridabad scores poorly in various factors such as road length (0.000), agricultural electricity connections (0.053), and primary agricultural credit societies (0.000) that contributing to its low overall SEI (0.309) along with district Charkhi Dadri struggles in terms of female literacy (0.000) and access to primary agricultural credit societies (0.185) which resulted in its poor overall SEI (0.351) showed significant social gaps that require focused interventions to enhance equity and access to basic services. Nuh registers the lowest SEI (0.271) primarily due to low scores in female literacy (0.014), infant mortality (0.013) and road length (0.360). Despite a strong performance in organized sector employment (1.000) Nuh faces substantial social challenges, especially in educational and infrastructural areas, underscoring the need for targeted policy measures to uplift its social equity standing. Furthermore, the results revealed that while some districts like Sirsa, Hisar, and Karnal showed commitment to equitable social development other like Faridabad, Charkhi Dadri, and Nuh highlighted areas where urgent attention is needed.

Sustainable livelihood security index (SLSI)

The district-wise indices (Table 6) for the Sustainable Livelihood Security Index (SLSI) evaluated by summation of the Economic Efficiency Index (EEI), Ecological Security Index (ESI) and Social Equity Index (SEI) along with their respective calculated weights. Also, by using the radar chart (Fig. 2) helps to compare the performance of districts across four indices. They showed that Sirsa (0.629) leads with the highest SLSI score as strong performance across the three dimensions. Karnal (0.625) follows closely second highest SLSI driven by its impressive performance in social equity (0.745)which is the highest among all districts. Further Hisar (0.580) also stands out with an SLSI score showed balanced performance as evidence followed by Fatehabad (0.568) and Yamunanagar (0.551) also secured good SLSI score highly. Conversely, Faridabad and Palwal has exhibited the lowest SLSI scores as 0.318 and 0.373 respectively because Faridabad faces major challenges in ecological security (0.233) and social equity (0.309) suggesting that both environmental management and social infrastructure required attention. Palwal similarly struggles in economic efficiency (0.260) and social equity (0.410) which reflecting the need for targeted interventions in these areas to improve its livelihood security. Similarly, Nuh (0.415) also showed very low SLSI scores mainly due to weak performance in social equity (0.271) and suggesting that needs to focus on social development indicators like education and healthcare to improve its overall sustainability. Districts such as Gurgaon (0.492) and Panchkula (0.485) have performed moderately in overall sustainability. This mainly due to that Gurgaon excels in economic efficiency (0.585),but lags in social equity (0.375) which highlighting an imbalance between economic growth and social welfare whereas Panchkula performed well in ecological security (0.631) but struggles with social equity (SEI = 0.300) that pointing to potential areas for policy intervention. The overall index values of four indices for Haryana (Fig. 3) were as follows i.e., Economic Efficiency Index (0.467), Ecological Security Index (0.534), Social Equity Index (0.500) and Sustainable Livelihood Security Index (SLSI) at 0.501. These values indicated a balanced performance across the indices only highlighting the need for improvement in economic efficiency and social equity but showing relatively stronger outcomes in ecological security and sustainable livelihoods of farm households in Haryana.

Table 7 revealed the rankings of the different districts based on the calculated scores of Economic Efficiency Index (EEI), Ecological Security Index (ESI), Sustainable Security Index (SSI), and sustainable Livelihood Security Index (SLSI). They provide a detailed assessment of the farm sustainability performance of every district. The rankings are further categorized into four distinct categories: least sustainable, moderately sustainable, sustainable, and highly sustainable. Each of these categories are displayed clearly on the study area map (Fig. 4). Thus, SLSI provides valuable insights into the strengths and weaknesses of different districts in Haryana i.e., districts like Sirsa, Karnal, and Hisar show strong, balanced performances, others like Faridabad and Palwal need significant improvements in ecological and social dimensions. The study revealed that only eleven districts out of 22 districts in Haryana (about 1/2th ) had an index of SLSI above 0.5, while remaining had SLSI value lower than 0.49 that indicates Haryana is sustainable. Similar findings have been reported by Bharti and Sen26 found that only about 1/4th of Bihar’s districts scored above 0.5 on the sustainable Livelihood Security Index (SLSI), while around half had SLSI values below 0.4 and suggests that overall south Bihar exhibited better agricultural sustainability than north Bihar.

EEI, ESI, SEI and SLSI maps of Haryana, India.Note: the map in this figure was created using the open-access, free online tool “Paintmaps” https://paintmaps.com/map-charts/246c/Haryana-map-chart which does not require any subscription and it is a free, online, interactive map chart generating tool.

As presented in Table 8, about 27.14 million people in the state of Haryana are situated within areas classified as ‘less sustainable’ and ‘moderately sustainable,’ encompassing 51.8% and 34% of the state’s total geographical area, respectively. These regions face vulnerabilities related to climate change, forest cover loss, and ecosystem service degradation. The ‘moderately sustainable’ category includes a population of 20.74 million. This data underscores the necessity for a critical review of policy interventions and development strategies in the state, with a primary emphasis on districts falling under the ‘less sustainable’ and ‘moderately sustainable’ SLSI categories. Addressing these concerns is imperative for achieving inclusive growth and ensuring the well-being of the residents.

Policy implications and conclusion

The study integrated economic efficiency, ecological security, and social equity dimensions by selecting suitable indicators and employing Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to eliminate spatial variations among districts to analysis the sustainable development in Haryana by using the Sustainable Livelihood Security Index (SLSI) as a evaluative tool. The empirical analysis of the Economic Efficiency Index (EEI), Ecological Security Index (ESI), Social Equity Index (SEI) and Sustainable Livelihood Security Index (SLSI) in Haryana revealed significant policy implications for promoting sustainable development across districts in the state of Haryana.

-

Targeted Agricultural Investments: Districts with SLSI values below 0.4, indicating poor conditions for Sustainable Development Agriculture (SDA) that should be prioritized for high-level agricultural investments which includes allocating resources strategically to enhance agricultural productivity, promote sustainable practices and address specific challenges in the identified districts.

-

Strategic Focus on Afforestation and Livestock Development: If the ESI values of a district are lower than the other two indices that emphasis should be placed on development projects related to afforestation, agro-forestry, cultivated area, and livestock development.

-

Equity-Enhancing Social Programs: If SEI values of a district are lower than both ESI and EEI, priority should be given to equity-enhancing initiatives which includes investments in education, healthcare facilities, improved sanitation, rural infrastructure development (including road connectivity and electrification) and other social programs to address disparities and promote inclusive growth.

-

Sustainable Agricultural Systems: To develop a sustainable agricultural system, there is a need for the appropriate utilization of local resources and effective environmental management which involves empowering farming communities by leveraging local knowledge, skills, cultural practices, and institutions.

Limitations

The study provides valuable insights into the agricultural sustainability of Haryana, it is subject to several kinds of limitations. Initially, the availability, completeness, and reliability of data have restricted due to the dependence on secondary data sources including government reports and district-level surveys. Differences in reporting standards and collection methodologies can also end up in inaccuracies or inconsistencies in these data sources. Furthermore, the results may have been influenced by the potential biases that are inherent in secondary data, such as regional disparities and variations in data quality across districts. Although the 28 sustainability indicators selected are exhaustive, they are predicated on assumptions regarding the most pertinent factors for agricultural sustainability, and it is possible that other significant indicators were disregarded. Also, because the study uses data from only one point in time, it cannot fully show how sustainability changes and develops over time. While Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is useful for reducing data complexity, it may miss some of the more complex, non-linear interactions between variables and assumes that relationships are linear, which could has affected how we interpret the principal components. Finally, the study’s focus on Haryana limits the generalizability of the findings to regions with different socio-economic and environmental conditions. These limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting the results. Future research could address these challenges to enable more comprehensive and robust assessments of sustainability in agricultural systems across diverse contexts.

Data availability

The dataset for the present study is available at public domain (https://esaharyana.gov.in/state-statistical-abstract-of-haryana/). The data sheets which were used for the analysis to obtain the results may be shared by the corresponding author on logical request.

Change history

01 September 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17807-3

References

WCED. World commission on environment and development. Our common future 17(1), 1–91 (1987).

Kotwal, P. C., Omprakash, M. D., Gairola, S. & Dugaya, D. Ecological indicators: Imperative to sustainable forest management. Ecol. Indic. 8(1), 104–107 (2008).

Singh, R. K., Murty, H. R., Gupta, S. K. & Dikshit, A. K. An overview of sustainability assessment methodologies. Ecol. Indic. 15(1), 281–299 (2012).

Saleth, R. M., and Swaminathan, M. S. Sustainable livelihood security at the household level: Concept and evaluation methodology. In Proceedings of an interdisciplinary dialogue on ecotechnology and rural employment, pp. 12–15 (1993).

Misra, V. N. & Rao, M. G. Trade policy, agricultural growth and rural poor: indian experience, 1978–79 to 1999–2000. Econ. Polit. Wkl. 38(42), 4588–4603 (2003).

Bostrom, M. The problematic social dimension of sustainable development: The case of the forest stewardship council. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 19(1), 3–15 (2012).

Swaminathan, M. S. From Stockholm to Rio de Janeiro: the road to sustainable agriculture. MS Swaminathan Research Foundation, Centre for Research on Sustainable Agricultural and Rural Development. (1991).

Vercelli, A. Sustainable development and the freedom of future generations. In Sustainability: Dynamics and uncertainty. (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 1998).

Harris JM. Sustainability and sustainable development. http://www.isecoeco.org/pdf/susdev.pdf. (2003). Accessed 18 September 2023.

Ikerd, J. Two related but distinctly different concepts: Organic farming and sustainable agriculture. Small Farm Today 10(1), 30–31 (1993).

Pretty, J. N. Regenerating agriculture: Policies and practice for sustainability and self-reliance (Earthscan, London, 1995).

Lynam, J. K. & Herdt, R. W. Sense and sustainability: Sustainability as an objective in international agricultural research. Agric. Econ. 3(4), 381–398 (1989).

Beus, C. E. & Dunlap, R. E. Agricultural paradigms and the practice of agriculture. Rural Sociol. 59(4), 620–635 (1994).

Wang, S. One hundred faces of sustainable forest management. For. Policy Econ. 6(4), 205–213 (2004).

Hatai, L. D. & Sen, C. An economic analysis of agricultural sustainability in Orissa. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 21(2), 273–282 (2008).

Bohringer, C. & Jochem, P. E. Measuring the immeasurable—a survey of sustainability indices. Ecol. Econ. 63(1), 1–8 (2007).

Hickel, J. The sustainable development index: Measuring the ecological efficiency of human development in the anthropocene. Ecol. Econ. 167(1), 106331 (2020).

Fredericks, S. E. Justice in sustainability indicators and indexes. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 19(6), 490–499 (2012).

Nambiar, K. K. M., Gupta, A. P., Fu, Q. & Li, S. Biophysical, chemical and socio-economic indicators for assessing agricultural sustainability in the Chinese coastal zone. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 87(2), 209–214 (2001).

Pearson, K. Principal components analysis. Lond. Edin. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 6(2), 559–571 (1901).

Hotelling, H. Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. J. Educ. Psychol. 24(6), 417–423 (1933).

Rajesh, S., Jain, S. & Sharma, P. Inherent vulnerability assessment of rural households based on socio-economic indicators using categorical principal component analysis: A case study of Kimsar region, Uttarakhand. Ecol. Indic. 85(1), 93–104 (2018).

De, D. & Das, C. S. Measuring livelihood sustainability by PCA in Indian Sundarban. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23(3), 18424–18442 (2021).

UNDP. United Nations Development Programme (Oxford University, London, 2006).

Iyengar, N. S. & Sudarshan, P. A method of classifying regions from multivariate data. Econ. Polit. Wkl. 17(51), 2047–2052 (1982).

Bharti, D. K. & Sen, C. Agricultural sustainability in Bihar: An evaluation of relative status of different districts. J. Agric. Dev. Policy 9(2), 1–13 (1997).

Funding

The research did not receive any financial assistance or funding from any internal or external agencies or institutions. All the work and expenses involved in the study were fully supported covered by the authors personal funding themselves.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributionData collection and analysis were conducted by G.J.T., S.B. and J.K.B. The manuscript has collectively written and authored byG.J.T., S.B. and J.K.B., D.K.B., N.B. and J.S.P. Finally, the complete research paper underwent examination and finalization by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the order of the author names, which was incorrectly given as G. Johns Tiyndel, Jitender Kumar Bhatia, Sanjay Bhyan, Dalip Kumar Bishnoi, Janailin S. Papang & Nitin Bhardwaj. Additionally, this Article contained an error in the spelling of the author Sanjay which was incorrectly given as Sanjay Bhyan.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tiyndel, G.J., Sanjay, Bhatia, J.K. et al. Measuring farm sustainability index: priorities for sustaining livelihoods of farm households in Haryana, India. Sci Rep 15, 13962 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84004-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84004-z