Abstract

Geologic records of tropical cyclones (TCs) in low-energy, back-barrier environments are established by identifying marine sediments via their allochthonous biogeochemical signal. These records have the potential to reconstruct TC intensity and frequency through time. However, modern analog studies are needed to understand which biogeochemical indicators of overwash sediments are best preserved and how post-depositional changes may affect their preservation. Here, we examine the overwash sediments of two successive land-falling, high-intensity TCs: Hurricane Ian in 2022 and Hurricane Irma in 2017. Hurricane Ian’s overwash sediments at two mangrove sites, including one directly along (Matlacha Pass) and one other distal from (Blackwater Bay) Hurricane Ian’s path through southwest Florida, USA, were identified as a light gray very poorly to poorly sorted coarse silty sand with marine microfossils and geochemical marine signature. Hurricane Irma’s overwash sediments remained identifiable from post-Irma sediments at Blackwater Bay as a gray poorly sorted coarse silt with a marine microfossil signature but lacking a distinctive geochemical signature. The identification of overwash sediments left by TCs occurring in within five years demonstrates the high preservation potential of overwash sediments in low-energy, mangrove environments. Similar environments can be utilized to advance paleotempestology studies in southwest Florida.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tropical cyclones (TCs) are among the most dangerous natural hazards in terms of loss of life and damage from winds and storm-related flooding1. In the United States, the Atlantic and Gulf coasts are at the highest risk of hurricanes due to the west-northwest propagation of TCs formed in the Atlantic Ocean1. From 1980–2022, TCs totaled 53.4% of all billion-dollar disasters with an average event cost of $22.4 billion per TC in the USA2. In 2022, TCs accounted for 182 deaths and 67.1% of all domestic billion-dollar disasters2. Rising sea level and changes in TC activity (e.g., duration, intensity, track) from anthropogenic climate warming is expected to increase overall TC damage3,4. At the same time, the impacts of individual TCs are expected to increase in cost and destruction, reflecting population growth and rising economic value of coastal communities5.

To improve our understanding of TC hazards along coastlines, scientists rely on paleotempestology studies to extend the record of TC frequency beyond the historical record. In addition to biological archives from corals6, stalagmites7, and tree rings8 that have been found to extend records of TC frequency, many successful studies utilize the geologic record to identify TC signatures in shallow and terrestrial depositional environments9,10,11,12,13,14. Regions vulnerable to landfalling TCs have the potential to archive long-term geologic records of past events in the form of overwash sediments15,16,17,18. Overwash sediments are recognized as layers of allochthonous sediments overlying a sharp (< 1 mm) unconformable contact and are often preserved in low-energy coastal environments such as mangroves, salt marshes, and lagoons18,19,20. Paleotempestology studies are aided by investigations of modern TC overwash sediments, which are fundamental to identifying storm-surge events in the geologic record because they serve as a modern analog for distinguishing the properties of an overwash deposit from those of the underlying low-energy coastal sediments18,21,22,23.

However, questions remain regarding the preservation potential of overwash sediments over centennial to millennial timescales in tropical mangrove environments vulnerable to repeated, high-intensity hurricanes. Paleotempestological studies rely on the completeness of the record favored by events with a high sedimentation rate in a low-energy depositional environment and a lack of bioturbation16,18,24,25. However, little is known about the preservation potential of overwash sediments from successive high-intensity TCs, which may rework or remove evidence of overwash sediments from previous TCs15,26. In southwest Florida, major hurricanes have a return period of 5–7 years27 and therefore a higher likelihood that overwash deposits of previous storms do not survive. Therefore, the temporal variability of TC occurrence and their long-term preservation in coastal environments throughout southwest Florida is unclear. An example of one such question is: can TC overwash sediments from successive (~ 5 years) high-intensity hurricanes remain uniquely identifiable in mangrove environments following their deposition?

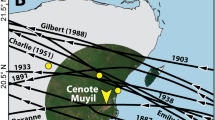

On 10 September 2017, Hurricane Irma made landfall in the Lower Florida Keys at Category 4 intensity with maximum sustained wind speeds of 213 km/h and storm surge of 2.4 m above mean higher high water (MHHW) before making subsequent landfall near the Ten Thousands National Wildlife Refuge in southwest Florida at Category 3 intensity with maximum sustained wind speeds of 185 km/h and storms surge of 1.9 m above MHHW (Fig. 1)28. A study by Joyse et al.29 investigated five sites in the Lower Florida Keys and the Ten Thousand Islands National Wildlife Refuge, southwest Florida (USA) 2 to 3 months and 22 months after Hurricane Irma made landfall. Joyse et al.29 described the stratigraphic, sedimentological, microfossil (foraminifera and diatoms), and geochemical (stable carbon isotopes and C/N values) indicators of Hurricane Irma’s overwash deposit. Results after both sampling periods identified a sharp contact separating the underlying mangrove peat from the overwash sediment, anomalous carbonate silts and sands with lower organic matter content (% OM), and calcareous marine foraminifera species as strong evidence for differentiating Irma’s overwash deposit from underlying mangrove peats. On 28 September 2022, Hurricane Ian made landfall at Cayo Costa, southwest Florida at Category 4 intensity with maximum sustained wind speeds of 240 km/h and storm surge of 3.98 m above MHHW30.

Map figure of study area: Matlacha Pass and Blackwater Bay, southwest Florida, USA. Large map shows the location of Matlacha Pass and Blackwater Bay alongside Hurricane Ian’s track as it passed north-northwest across peninsular Florida, increasing in intensity to Category 4 on the Saffir-Simpson scale before making landfall and crossing Matlacha Pass. Inset maps show location of each site (top: Matlacha Pass; bottom: Blackwater Bay) and distance from storm track. Map created using ArcGIS Pro version 2.9.2.

In this study, we aim to improve our understanding of TC overwash sediments by 1) documenting the stratigraphic, sedimentological (grain-size), microfossil (foraminifera), and geochemical (% OM and δ13Cbulk) characteristics of Hurricane Ian, a Category 4 TC that made landfall in southwest Florida five years after Hurricane Irma at two mangrove sites, one directly along (Matlacha Pass) and the other distal from (Blackwater Bay) Hurricane Ian’s path (Fig. 1), and 2) assessing the preservation potential of Hurricane Irma overwash sediments following Hurricane Ian at Blackwater Bay, Ten Thousand Islands National Wildlife Refuge due to previously published data on Hurricane Irma’s deposit by Joyse et al.29. Results were analyzed using hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis to identify key indicators capable of differentiating hurricane overwash sediments from pre-hurricane mangrove peat. To explore the preservation potential of overwash sediments in mangroves impacted by repeated, high-intensity TCs in the southwestern Florida region, we examined Hurricane Irma overwash sediments at Blackwater Bay for evidence of post-depositional reworking and employed hierarchical clustering to explore whether or not sedimentation in the five years between Hurricanes Irma and Ian was sufficient in preserving a distinct Irma overwash deposit.

Results

Hurricane Ian overwash sediments at Matlacha Pass, Charlotte Harbor

Hurricane Ian made landfall in 2022 at Cayo Costa and continued its path approximately 12 km north of Matlacha Pass (Fig. 1)30. Storm surge observations by the U.S. Geological Survey at Fort Myers, Florida, which is approximately 23 km to the southeast of our study site, recorded a storm surge height of 4.1 m above mean tide level (MTL) and inundation distance of 3.9 km31. Tracing of the deposit farther inland was hindered by wide channels, thick vegetation, and a lack of safe road access. Flow height estimates from organic debris (e.g., algae, seagrass, and other dead plant matter) within the wrack line ranged from 1.65 to 3.27 m above MTL. Surface vegetation at Matlacha Pass is dominated by tall mangroves, mainly Rhizophora mangle (red mangrove) and to a lesser degree Laguncularia racemosa (white mangrove) and Avicennia germinans (black mangrove).

Across the transect, Hurricane Ian’s overwash deposit ranged in thickness from 3 to 5 cm and was characterized by coarser sediment, reduced % OM, higher δ13Cbulk values, and more abundant calcareous marine foraminifera compared to the underlying mangrove peat (Fig. 2). A sharp (< 1 mm) contact separated the Hurricane Ian overwash deposit from the underlying sediment. The overwash sediments were a light gray, moderately well to very poorly sorted (0.50 to 2.06 ɸ) very coarse silty sand (mean: 4.25 ɸ) with a low proportion of OM (mean: 12.2%), and mean δ13Cbulk values of -13.0‰ (Table 1). High-resolution grain-size analysis of Hurricane Ian sediments from Station 1 indicated an upward-fining trend from 3 cm depth (mean 2.89 Φ) to the top of the overwash layer (mean 3.81 Φ) at 0 cm depth (Fig. 3). The underlying pre-Ian unit was a red, poorly to very poorly sorted (1.45 to 2.12 ɸ) sandy muddy mangrove peat (mean: 4.67 ɸ) with a higher proportion of OM (mean: 42.6%), and mean δ13Cbulk values of -27.9‰. High-resolution grain-size analysis of the underlying mangrove peat displayed no clear fining or coarsening trend (Fig. 3). Concentrations of biogenic carbonate (% CaCO3) were higher in the overwash deposit (mean: 13.2%) compared to the underlying mangrove peat (mean: 5.8%). Marine calcareous foraminifera species such as Ammonia tepida and Haynesina germanica were present at high relative abundances (91 ± 8%) within Ian’s overwash deposit. In contrast, the foraminiferal assemblage of the underlying mangrove peat contained predominantly (88 ± 19%) intertidal agglutinated species such as Trochammina inflata and Siphotrochammina lobata. Samples of foraminifera from Ian’s overwash deposit had a higher species diversity (18 ± 5 species) and a higher specimen count (1194 ± 433 specimens per cc) compared to pre-Ian mangrove sediments (3 ± 2 species and 71 ± 86 specimens per cc, respectively).

Modern transect results from Matlacha Pass, Florida. From top to bottom: % organic matter (OM) using loss-on-ignition, δ13Cbulk (‰), mean grain size (Φ), and relative foraminifera abundance of species along a mangrove forest transect relative to mean tide level (MTL) that started near open water and moved inland (S1–S8) at Matlacha Pass. Results show Hurricane Ian overwash deposit has lower organic matter content (mean: 12.5%), higher C isotopic values (mean: -13 ‰), and coarser sediment (mean 4.13Φ) than pre-Ian mangrove peat. Foraminiferal abundances in Ian’s overwash deposit at the Matlacha site exhibit an increase in species diversity (18 species on average) and in specimen counts (1194 specimens/cc on average) compared to pre-Ian mangrove sediments (3 species and 71 specimens/cc on average).

Downcore results of Hurricane Ian sediments and underlying sediments from Matlacha Pass (top) and Blackwater Bay (bottom), Florida. From left to right: photo of core taken in the field. At Matlacha Pass, Unit 1 is 0–3.5 cm depth and Unit 2 is 3.5–6 cm depth. At Blackwater Bay, Unit 1 is 0–1 cm depth, Unit 2 is shown 1–4.5 cm depth, Unit 3 is 4.6–6 cm depth, and Unit 4 is 6–8 cm depth. Scatter plots display grain size statistics mean and sorting (Φ), % organic matter (OM) from loss-on-ignition, δ13Cbulk, % sand, % mud, % calcareous foraminifera, and % agglutinated foraminifera.

Hurricanes Ian and Irma overwash sediments at Blackwater Bay, Ten Thousand Islands

Hurricane Ian’s path was approximately 103 km north-northwest of Blackwater Bay30 (Fig. 1). Storm surge observations by the U.S. Geological Survey at Marco Island, Florida, which is approximately 13 km to the west of our study site, recorded a storm surge height of 2.3 m above mean tide level (MTL) and inundation distance of 2.1 km31. We were unable to estimate local flood height because of a lack of visible debris from Hurricane Ian. Surface vegetation at Blackwater Bay is dominated by tall mangroves, mainly Rhizophora mangle (red mangrove) and to a lesser degree Laguncularia racemosa (white mangrove) and Avicennia germinans (black mangrove).

Across the transect, Hurricane Ian’s overwash sediments were a gray, poorly sorted (1.77 to 1.89 ɸ), sandy mud (mean 5.22 ɸ) that ranged in thickness from 0.5 to 8 cm and was characterized by a lower proportion of OM (mean: 16%), high δ13Cbulk values (mean -15.1‰), and abundant calcareous marine foraminifera species (Fig. 4). Stratigraphic observations from a sediment core at Station 12, located in the interior of a Blackwater Bay mangrove island, revealed four distinct stratigraphic units (Fig. 3). Unit 1, the Ian overwash deposit from 0 to 1 cm depth, was a light gray, very poorly sorted (2.06 ɸ), low-organic (16% OM) very coarse silt (mean: 4.85 ɸ) with a δ13Cbulk value of -14.9‰ (Table 1). The foraminiferal assemblage of Unit 1 was mainly populated by Ammonia tepida and Haynesina germanica, which made up over 60% of the sample, while species with lower abundances (e.g., Ammonia beccarii and Bolivina spp.) constituted a relatively small fraction of the sample (Supplementary Fig. 1). A sharp, erosive contact separated the Ian overwash sediment from Unit 2, which was found at 1 to 4.5 cm depth and was a gray-brown, poorly sorted (1.33 to 1.97 Φ), low-organic (mean OM: 12%) very coarse silt (mean: 4.29 Φ) with a mean δ13Cbulk value of -11.9‰. The foraminiferal assemblage of Unit 2 was similar to that of Unit 1, where Ammonia tepida and Haynesina germanica had the largest abundances (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, species with lower abundances, such as Ammonia beccarii, Bolivina spp., and Cribroelphidium poeyanum comprised a larger percentage of the sample compared to Unit 1 (Supplementary Fig. 1). A gradational (> 1 cm) contact separated Unit 2 (post-Irma sediment) from Unit 3, the Irma overwash deposit. The Irma overwash sediment was found at 4.5 to 6 cm and was a gray, poorly sorted (mean: 1.82 Φ), low-organic (mean: 8% OM) very coarse silt (mean: 3.88 Φ) with a mean δ13Cbulk value of -17.9‰. The foraminiferal assemblage of Unit 3 was largely composed of Ammonia tepida and Ammonia beccarii specimens, with smaller abundances of Haynesina germanica and Bolivina spp (Supplementary Fig. 1). A sharp, contact separated the Irma overwash sediment from Unit 4, which was the underlying mangrove peat and was found at 6 to 25 cm depth. Unit 4 was a dark brown–red, poorly sorted (mean: 1.69 Φ), organic-rich (mean: 24% OM) coarse silt (mean: 5.73 Φ) with a mean δ13Cbulk value of -22.7‰. The foraminiferal assemblage of Unit 4 was dominated by Ammonia tepida with smaller abundances of the agglutinated species of Trochammina inflata and Ammotium fragile (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Modern transect results from Blackwater Bay, Florida. From top to bottom: % organic matter (OM) using loss-on-ignition, δ13Cbulk (‰), mean grain size (Φ), and relative foraminifera abundance of species along a mangrove forest transect relative to mean tide level that started near open water and moved inland (S1–S12) at Blackwater Bay. Results show Hurricane Ian overwash deposit has low organic matter content (mean: 16%), high C isotopic values (mean: -15.1 ‰), and coarse sediment (mean 5.65 Φ). Foraminiferal abundances in Ian’s overwash deposit at the Blackwater site exhibit a high abundance of calcareous species (95 ± 6%) and high species diversity (16 species on average) and in specimen counts (586 specimens/cc on average).

Identifying key biogeochemical indicators of hurricane overwash sediment in southwest Florida

Hierarchical clustering results of our samples from Matlacha Pass show separation of Ian compared to the underlying pre-Ian sediment (Fig. 5). A PCA biplot of samples from the core at Station 1 distinguishes sediments across Axis 1 (93% of the variance) and Axis 2 (6% of the variance). Along Axis 1, positive loading factors include: % OM, % agglutinated foraminifera, % mud, and grain-size sorting whereas negative loading factors include: % sand, % calcareous foraminifera, higher δ13Cbulk values.

(top) Hierarchical cluster results and (bottom) PCA sample-environment biplot results from Blackwater Bay (left) and Matlacha Pass (right) cores. Station symbols indicate stratigraphic unit (Unit 1 = circle; Unit 2 = cross; Unit 3 = triangle; Unit 4 = square) and colors indicate cluster (blue = overwash sediment; gray = very coarse silt with organics; green = mangrove peat). Vectors indicate environmental variables.

Hierarchical clustering results of our samples from Blackwater Bay identified three distinct clusters: 1) pre-Irma mangrove peat, 2) hurricane overwash sediments, and 3) intervening sedimentation between Hurricanes Irma and Ian (Fig. 5). A PCA biplot of the core distinguishes sediments across Axis 1 (87% of variance) and 2 (12% of variance). Similar to Matlacha Pass, positive loadings along Axis 1 include: higher % mud, % OM, and % agglutinated foraminifera whereas negative loadings include higher % of sand, %calcareous foraminifera, and higher δ13Cbulk values. Grain-size sorting provides the primary positive loading factor along Axis 2, which further separates the Hurricane Ian and Irma overwash sediments from the intervening sediments in Unit 2.

Discussion and conclusions

Despite the difference in proximity to Hurricane Ian’s path between Matlacha Pass and Blackwater Bay (Fig. 1), Hurricane Ian’s overwash deposit is distinguishable from the underlying mangrove peat in both locations. Previous studies of TC deposits from the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf coasts have identified the presence of a sharp contact separating the overlying coarse sediment from the underlying stratigraphic unit as indicative of overwash deposition from a high-energy storm surge16,20 because TCs erode marine and coastal sediments and transport them landward, where they may become deposited and preserved in low-energy environments (e.g., coastal lakes, back-barrier lagoons, salt marshes) dominated by silts and clays12,16,17,18,24,32. Although there are many factors capable of influencing the deposition of TC overwash sediments (e.g., storm intensity, storm surge height, shoreline morphology, and distance and orientation of the storm track to shore15,16,18,24), similarities in Hurricane Ian’s impact (i.e., high intensity (≥ Category 3) and high (> 1 m above MTL) storm surge height as it passed through southwest Florida allowed us to identify Hurricane Ian’s deposit at Matlacha Pass and Blackwater Bay. Hurricane Ian overwash sediment characteristics at both sites consisted of light gray, coarse silty sand with less organics, higher δ13Cbulk values, and more calcareous foraminifera compared to the underlying mangrove peat, which align with indicators reported from previous studies characterizing hurricane overwash sediments in Florida29,33,34,35. We attribute these similarities to the fact that, in southwest Florida, sediments offshore and nearshore are predominantly siliciclastic and carbonate whereas sediments in onshore environments are often organic-rich peat due to the high density of mangrove forests36,37,38. Additionally, the presence of marine microfossils (e.g., foraminifera) and higher δ13Cbulk values in Hurricane Ian overwash sediments provides evidence in support of onshore sediment transport from marine or coastal sources23,29,33,39,40. Although similar characteristics have been attributed to tsunami deposits, geologic setting (i.e., shorelines along or near an active margin) and stratigraphic context (e.g., liquefaction structures, evidence of synchronous land-level change) are important clues to help distinguish a tsunami deposit from a storm deposit41. In the case of southwest Florida, which is not located near an active margin, we therefore present our findings in the context of hurricane overwash sediments.

Our stratigraphic observations 5 months after Hurricane Ian (5.5 years after Hurricane Irma) at Blackwater Bay is the first study to explore the potential impacts of post-depositional preservation of modern overwash sediments from successive high-intensity hurricanes in mangrove environments. Three months after landfall, Joyse et al.29 identified and characterized Hurricane Irma overwash sediments at Blackwater Bay, which were light gray, coarse to very coarse silt with less organics, and higher δ13Cbulk values compared to the underlying mangrove peat. Additional observations made 22 months after landfall found that Hurricane Irma overwash sediments had consistently less organics and higher δ13Cbulk values than underlying mangrove peats29. In this study, we correlate our Unit 3 with Hurricane Irma deposition due to similarities in sedimentological characteristics and relative stratigraphic position as described by Joyse et al.29. A gradational contact separates Unit 3 from the overlying Unit 2, which we interpret as post-Irma sedimentation that reflects a period of mangrove forest dieback and regrowth42 as indicated by the gradual increase in % OM within the unit. However, the higher inorganic content, coarser grain size, and higher δ13C values in Unit 2 compared to Unit 4 (pre-Irma sediments) suggests some post-depositional mixing via bioturbation or tidal action may have occurred between Hurricane Irma overwash deposition and post-Irma mangrove peat sedimentation, which may have dampened the mangrove signature in Unit 2.

A sharp contact delineates Unit 2 from the overlying Unit 1, which was the Hurricane Ian overwash sediment. Our results therefore indicate a sediment accumulation rate of ~ 7 mm/yr between the Hurricanes Irma and Ian, which is in agreement with other studies in the region43. This sediment accumulation rate can be assumed to be a minimum estimate as sediment would have been eroded as a result of Hurricane Ian’s storm surge; however, the intervening five years between the two events marked a time during which there was no direct hit by a major TC and the accumulation rate was high enough such that it produced a layer of sediment that protected Hurricane Irma’s overwash deposit from erosion during Hurricane Ian’s storm surge in Blackwater Bay. It is important to note that with a conservative accumulation rate of ~ 7 mm/yr, we should expect to see an overwash deposit from Hurricane Wilma (2005) approximately 8 to 9 cm below that of Hurricane Irma. No such overwash deposit was identified during stratigraphy recorded in the field (Fig. 4). However, because this study aimed to investigate the modern deposit of Hurricane Ian and its implications for Hurricane Irma’s deposit, sediments were only analyzed for sedimentary, geochemical, and microfossil indicators to a depth of 8 cm. Additional, older overwash deposits likely exist at depths greater than that of Hurricane Irma’s deposit but samples were not collected to an appropriate depth in this study to examine older deposits.

Using PCA analysis on our modern overwash deposits, we determine that terrestrial (e.g., higher % of mud, OM, and agglutinated foraminifera) versus marine inputs (e.g., higher % of sand, calcareous foraminifera, and δ13Cbulk values) were instrumental in differentiating mangrove sediments from the Ian overwash sediments. Previous work aimed at characterizing terrestrial and marine biogeohemical signatures show that factors such as increased % OM36,37,38, agglutinated foraminifera40,44, and smaller grain size12,16,18,24,32 have been shown to be indicative of terrestrial inputs whereas coarser grain size45,46,47, calcareous foraminifera18,23,39,40, and higher δ13C values48,49 are proxies indicative of marine inputs. Our findings demonstrate that foraminifera, grain size, % OM, and δ13Cbulk analyses can be used to identify Ian overwash sediment from underlying mangrove sediment across all sites and samples corroborates earlier work by Joyse et al.29 showing that grain size, % organic content, and microfossil foraminifera analyses provided the strongest evidence for differentiating Irma’s overwash deposit from underlying mangrove peats and are expected to identify Hurricane Irma’s overwash event within the geologic record. Similarly, a study by Yao et al.50 in the Florida Everglades explored the utility of grain size, % organic content, stable isotope, X-ray fluorescence, microfossil foraminifera, and pollen in identifying Hurricane Wilma overwash deposits. PCA revealed mean grain size, % OM, % water, % carbonate, elemental geochemical proxies (i.e., Ca and Sr concentrations, Ca/Ti ratio), and marine microfossil indicators were key indicators in identifying Hurricane Wilma deposits50.

In contrast to the other proxies measured, δ13Cbulk values did not show as clear of a distinction downcore. Although Unit 4 (pre-Irma) had δ13Cbulk values consistent with mangrove peat (mean –22.7 ‰), the overlying units had a range of higher, more marine-influenced values that are not easily interpretable as overwash layers from two distinct storms (Fig. 3). Joyse et al.29 found δ13Cbulk measured at a median value of –5.85‰ in Hurricane Irma’s overwash deposit was useful in distinguishing the deposit from underlying pre-Irma mangrove peats (median δ13Cbulk -20.1 ‰) two months after the storm’s landfall in Blackwater Bay. While δ13Cbulk values became slightly less distinct after 22 months at most sampling sites, they remained statistically different at Blackwater Bay with median δ13Cbulk values of –9.85‰ and –22.7‰ in the Irma overwash sediments and underlying mangrove peats, respectively19. Our results show δ13Cbulk values for Hurricane Irma’s overwash deposit continued to decrease to –17.9‰ when the deposit was resampled in March 2023 (5.5 years post-storm). However, the δ13Cbulk values of the underlying mangrove peats have remained consistent through time. These more ambiguous geochemical values within and in the sediments above Hurricane Irma’s overwash deposit may be due to mixing of sediment or from insufficient recovery of the mangrove environment post-Irma to result in more terrestrial δ13Cbulk values prior to the deposition of the Ian overwash deposit.

Hierarchical clustering results at Blackwater Bay and Matlacha show separation between hurricane overwash deposition compared to all other stratigraphic units, which demonstrates we are able to differentiate not only hurricane overwash sediments from mangrove sediments but also Hurricane Irma from Hurricane Ian. PCA analysis of samples from all four units at Blackwater Bay allowed us to examine the consistency of key indicators in identifying hurricane overwash sediments in southwest Florida mangroves (Fig. 5). Overall, grain size, % OM, and foraminifera can uniquely identify Ian and Irma overwash sediment from intervening mangrove peats, which corroborates similar findings from studies of Hurricanes Irma29 and Wilma50 (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table 1). The unique identification of two successive high-intensity hurricane events has implications for our understanding of TC frequency reconstructions from geologic records and the temporal variability of TCs through time. These results not only show the consistency of our proxies in identifying and distinguishing overwash sediments from multiple hurricanes, but also highlights the potential utility of prioritizing grain-size, loss-on-ignition, and microfossil foraminifera analyses to identify past TC overwash deposits in southwest Florida. We therefore recommend future paleotempestology studies in southwest Florida mangroves should employ high-resolution sampling and analysis of sedimentological and microfossil proxies combined with high-resolution dating techniques in order to identify paleo-TC overwash deposits.

Our findings identify a couple key characteristics regarding TC deposits in southwest Florida. First, Hurricane Ian’s overwash sediments can be used as a modern analog to identify geologic TC deposits in future paleotempestological studies due to the consistency of its characteristics in subtropical mangrove environments, which are distinct marine overwash sediment signatures (identified by foraminifera, grain size, % OM, and δ13Cbulk) compared to mangrove peat. Second, it is possible to differentiate multiple TC events occurring in short succession (~ 5 years) within the sediment record (specifically with foraminifera, grain size, and % OM) given enough time has passed and sediment accumulation is high enough to establish an intermediary layer of sediment, which is crucial for examining the frequency of TCs through time. At least 3.5 cm of sediment (e.g., not including sediment that was eroded by Hurricane Ian’s storm surge) were deposited between Hurricane Irma and Hurricane Ian. Therefore, it is also likely that events occurring at an even higher frequency could also be distinguished within the sediment record during periods of comparable deposition. However, paleotempestological studies aimed at establishing reoccurrence rates will require a combination of high-resolution sampling and advanced dating techniques to capture and date the TC deposit. These findings from the modern environment and recent past can be applied to better utilize mangrove environments to identify past TC events and aid in the study of how storm frequencies may be changing through time as we continue to experience a warming climate.

Methods

Field survey and sample collecting

In March 2023, five months after landfall, we described and collected Hurricane Ian overwash sediment at two locations in southwest Florida: 1) Matlacha Pass, Charlotte Harbor and 2) Blackwater Bay, Ten Thousand Islands National Wildlife Refuge (Fig. 1). The sites were chosen based on the presence of Hurricane Ian overwash sediments and the lack of sediment disturbance from site cleanup. Blackwater Bay was chosen to compare Ian’s overwash signature against Irma’s and the intervening five years, and the sampled locations were identified to closely match sites sampled by Joyse et al.29. Elevations were recorded using a Real-Time Kinematic Global Position System (RTK-GPS) and were referenced to the North American Vertical Datum NAVD88 (Supplementary Table 2). The sampling locations were related to mean tide level using VDatum51.

We used a 25 mm-diameter gouge corer to document changes in thickness and extent of Hurricane Ian overwash sediments. At each sampling station, we measured the surface elevation and described the depth, contact, color, and lithology of every stratigraphic unit. Sediment samples were collected along transects and from sediment cores for grain-size, loss-on-ignition, microfossil (foraminifera), and geochemical (stable carbon isotopes) analyses. At Matlacha Pass, we measured storm-surge flow heights, overwash sediment thickness, and collected samples of pre-Ian underlying sediment as well as Ian’s overwash sediment from 9 locations across a 150 m transect. At Blackwater Bay, modern samples were taken of the surface sediment (Hurricane Ian) to characterize Ian sediments. We revisited locations where the Hurricane Ian overwash sediment deposit was recorded to be thick and used a 50 mm-diameter gouge corer to retrieve a sediment core for laboratory analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2). We collected samples at 1-cm intervals within the deposit and the underlying layers (pre-Ian, Irma, and pre-Irma) in a short core up to a depth of 8 cm below the surface. Samples were collected in plastic sampling bags and refrigerated until they were measured for sedimentological, microfossil, and geochemical analyses.

Grain-size analysis

We measured grain-size distributions of Hurricane Ian overwash sediments and the underlying sediment. We used 30% H2O2 to digest the organic fraction of the samples prior to grain-size measurements using a Malvern Mastersizer 3000 laser particle-size analyzer52. GRADISTAT software53 was used to calculate the following grain size statistics according to Folk and Ward54: mean (average grain size), sorting (grain size variation), skewness (symmetry of the grain size distribution), and kurtosis (peakedness of the grain size distribution). We also report the 10th (d10), 50th (d50), and 90th (d90) percentiles of grain size diameters to identify fining or coarsening trends.

Microfossil analysis

We analyzed the foraminifera assemblages found in Hurricane Ian overwash sediments and the underlying mangrove sediments from each of the stations along the Matlacha Pass transect. At Blackwater Bay, we analyzed foraminifera assemblages of samples taken at 1-cm intervals from a short core to a depth of 8 cm and samples of Hurricane Ian’s overwash sediments taken from four samples along the transect, including the top of the short core.

Samples for foraminifera analysis were stored in buffered ethanol and dyed with Rose bengal upon collection to differentiate live vs dead specimens55. Samples of 1.25 cm3 volume were washed, and the 63- to 500-μm fraction of each sample were wet split into eight aliquots for counting56,57. Foraminifera were identified58,59,60,61,62 and counted wet to the species level using a binocular microscope at 20 to 40 × magnification. The number of live, broken, and abraded/corroded specimens were counted within each sample.

Geochemical and loss-on-ignition (LOI) analysis

We measured the stable carbon isotopic composition of bulk sediment of the Hurricane Ian overwash sediments and the underlying mangrove sediment. Carbon isotope ratios were measured by cavity ring-down laser spectroscopy (CRDS)63. Sediment samples were first freeze-dried in a Virtis™ benchtop freeze dryer to remove moisture and then ground into a fine powder in a Retsch™ ball mill. Approximately 2 mg (± 0.5 mg) of dry, homogenized bulk sediment was weighed on a Mettler Toledo™ XP56 microbalance with 4 µg precision, sealed in tin capsules, and flash combusted at 980 °C in a Costech™ ECS 4010 element analyzer using nitrogen carrier gas. Carbon isotope ratios of the resulting CO2 gas were analyzed in a Picarro™ G2201-i CRDS instrument in the Geochemistry Facility at Bryn Mawr College. Sediment carbon abundances were calculated from peak 12CO2 gas concentration values measured by CRDS (in-run analyses of internal standards were calibrated with standard reference material USGS40 (glutamic acid)). Reproducibility of carbon mass concentration was ± 0.8% (1 s.d.). Stable bulk carbon isotopic compositions (δ13Cbulk) are reported relative to Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (δ13CVPDB), calibrated by in-run analyses of USGS40. The median standard deviation of δ13Cbulk for sample replicates, and for internal and external standards interspersed among samples, is ± 0.23‰. We use previously reported δ13Cbulk values of marine particulate organic matter (-24 to -18‰)64 and mangrove litter (-32 to -27 ‰)65 from Florida to distinguish between marine or terrestrial sources of organic carbon in the sediment samples.

The organic matter abundance (% OM) of the Hurricane Ian overwash sediments and the underlying mangrove sediment was determined by loss-on-ignition (LOI) analysis66. Dried sample aliquots were placed into pre-weighed crucibles, combusted in a muffle furnace for 4 h at 550 °C, and the remaining ash was re-weighed to determine the organic matter abundance. The biogenic carbonate content (CaCO3%) was also measured by acid leaching (10% HCl) weighed bulk sample aliquots, triple rinsing with deionized water, drying the sample, and re-weighing.

Statistical analysis

Sedimentological, geochemical, and microfossil data were tested for normality using Shapiro–Wilk tests67. The test results for the majority of the datasets failed to reject the null hypothesis and supported that the datasets were sampled from a normal distribution. Therefore, grain size, organic content, δ 13Cbulk, and foraminifera datasets from pre-Ian overwash sediment and Ian overwash sediments were compared using Student t-tests68 to determine which datasets (if any) were statistically different (p-value < 0.05; Supplementary Table 1). The datasets were analyzed using the stats package in SciPy69.

Sedimentological and geochemical data from transect samples, along with foraminifera data from the short cores taken at the Matlacha Pass and Blackwater Bay sites, were analyzed using hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis (PCA) to identify samples with similar characteristics and which proxy or species had the greatest significance in clustering samples. The sedimentological and geochemical data included in clustering and PCA analyses included grain size (d10, d50, and d90), organic content measured via LOI, and δ13C. Foraminifera species with relative abundances greater than 5% in at least one sample per core were included in the clustering and PCA analyses. The data were clustered using Ward’s Minimum Variance Linkage Algorithm based on Euclidean distance with the hierarchical linkages and clustering packages in SciPy69. The PCA analysis was completed with CANOCO v 5.170.

Data availability

Supplementary material available in the online version. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to IH.

References

Dinan, T. & Wylie, D. Expected Costs of Damage From Hurricane Winds and Storm-Related Flooding. US Congr. Budg. Off. (2019)

Monthly Global Climate Report for December 2022. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report/global/202300 (2023).

Mendelsohn, R., Emanuel, K., Chonabayashi, S. & Bakkensen, L. The impact of climate change on global tropical cyclone damage. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 205–209 (2012).

Weaver, M. M. & Garner, A. J. Varying genesis and landfall locations for North Atlantic tropical cyclones in a warmer climate. Sci. Rep. 13, 5482 (2023).

Crossett, K., Ache, B., Pacheco, P. & Haber, K. National coastal population report, poepulation trends from 1970 to 2020. NOAA State Coast Rep. Ser. (2013).

Hetzinger, S. et al. Caribbean coral tracks Atlantic multidecadal oscillation and past hurricane activity. Geology 36, 11–14 (2008).

Frappier, A. B., Sahagian, D., Carpenter, S. J., González, L. A. & Frappier, B. R. Stalagmite stable isotope record of recent tropical cyclone events. Geology 35, 111–114 (2007).

Miller, D. L. et al. Tree-ring isotope records of tropical cyclone activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 14294–14297 (2006).

Donnelly, J. P. et al. Climate forcing of unprecedented intense-hurricane activity in the last 2000 years. Earths Future 3, 49–65 (2015).

Woodruff, J. D., Kanamaru, K., Kundu, S. & Cook, T. L. Depositional evidence for the kamikaze typhoons and links to changes in typhoon climatology. Geology 43, 91–94 (2015).

Nott, J. A 6000 year tropical cyclone record from Western Australia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 713–722 (2011).

Wallace, D. J., Woodruff, J. D., Anderson, J. B. & Donnelly, J. P. Palaeohurricane reconstructions from sedimentary archives along the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean Sea and western North Atlantic Ocean margins. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 388, 481–501 (2014).

Dashtgard, S. E., Löwemark, L., Wang, P.-L., Setiaji, R. A. & Vaucher, R. Geochemical evidence of tropical cyclone controls on shallow-marine sedimentation (Pliocene, Taiwan). Geology 49, 566–570 (2021).

Monica, S. B. et al. 4500-year paleohurricane record from the Western Gulf of Mexico, Coastal Central TX, USA. Mar. Geol. 473 (2024).

Hippensteel, S. P., Eastin, M. D. & Garcia, W. J. The geological legacy of Hurricane Irene: Implications for the fidelity of the paleo-storm record. GSA Today 23, 4–10 (2013).

Liu, K. & Fearn, M. L. Lake-sediment record of late Holocene hurricane activities from coastal Alabama. Geology 21, 793–796 (1993).

Donnelly, J. P. & Woodruff, J. D. Intense hurricane activity over the past 5,000 years controlled by El Niño and the West African monsoon. Nature 447, 465–468 (2007).

Liu, K. & Fearn, M. L. Reconstruction of prehistoric landfall frequencies of catastrophic hurricanes in Northwestern Florida from Lake Sediment Records. Quat. Res. 54, 238–245 (2000).

Liu, K. B. Paleotempestology: Principles, methods, and examples from Gulf Coast lake sediments. Hurric. Typhoons Past Present Future 13, 57 (2004).

Donnelly, J. P., Webb, T. III., Murnane, R. & Liu, K. B. Backbarrier sedimentary records of intense hurricane landfalls in the northeastern United States. Hurric. Typhoons Past Present Future 55, 58–95 (2004).

Donnelly, J. P. et al. 700 yr sedimentary record of intense hurricane landfalls in southern New England. GSA Bull. 113, 714–727 (2001).

Scileppi, E. & Donnelly, J. P. Sedimentary evidence of hurricane strikes in western Long Island, New York. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GC001463 (2007).

Hawkes, A. D. & Horton, B. P. Sedimentary record of storm deposits from Hurricane Ike, Galveston and San Luis Islands, Texas. Geomorphology 171–172, 180–189 (2012).

Brandon, C. M., Woodruff, J. D., Lane, D. P. & Donnelly, J. P. Tropical cyclone wind speed constraints from resultant storm surge deposition: a 2500 year reconstruction of hurricane activity from St. Marks, FL. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 14, 2993–3008 (2013).

Hippensteel, S. P. Preservation potential of storm deposits in South Carolina back-barrier marshes. J. Coast. Res. 24, 594–601 (2008).

Leatherman, S. P. & Williams, A. T. Lateral textural grading in overwash sediments. Earth Surf. Process. 2, 333–341 (1977).

Neumann, C. J. & McAdie, C. A revised National Hurricane Center NHC83 model (NHC90). NOAA Tech. Memo. NWS NHC 44.

Cangialosi, J. P., Latto, A. S. & Berg, R. Hurricane Irma (Tropical Cyclone Report No. AL112017). Natl. Hurric. Cent. 1–11 (2018).

Joyse, K. M. et al. The characteristics and preservation potential of Hurricane Irma’s overwash deposit in southern Florida, USA. Mar. Geol. 461, 107077 (2023).

Bucci, L., Alaka, L., Hagen, A. & Beven, J. Hurricane Ian. Natl. Hurric. Cent. Trop. Cyclone Rep. 72 (2023).

U.S. Geological Survey. Hurricane Ian Flood Event Viewer | U.S. Geological Survey. USGS Flood Event Viewer https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/hurricane-ian-flood-event-viewer (2022).

Donnelly, J. P. Evidence of Past Intense Tropical Cyclones from Backbarrier Salt Pond Sediments: A Case Study from Isla de Culebrita, Puerto Rico, USA. J. Coast. Res. 201–210 (2005).

Lane, P., Donnelly, J. P., Woodruff, J. D. & Hawkes, A. D. A decadally-resolved paleohurricane record archived in the late Holocene sediments of a Florida sinkhole. Mar. Geol. 287, 14–30 (2011).

Castañeda-Moyda, E. et al. Sediment and nutrient deposition associated with Hurricane Wilma in Mangroves of the Florida Coastal Everglades. Estuaries Coasts 33, 45–58 (2010).

Lagomasino, D. et al. Storm surge and ponding explain mangrove dieback in southwest Florida following Hurricane Irma. Nat. Commun. 12, 8 (2021).

Shier, D. E. Vermetid Reefs and Coastal Development in the Ten Thousand Islands Southwest Florida. GSA. Bull. 80, 485–508 (1969).

Davies, T. D. & Cohen, A. D. Composition and Significance of the Peat Deposits of Florida Bay. Bull. Mar. Sci. 44, 387–398 (1989).

Evans, M. W., Hine, A. C. & Belknap, D. F. Quaternary stratigraphy of the Charlotte Harbor estuarine-lagoon system, southwest Florida: Implications of the carbonate-siliciclastic transition. Mar. Geol. 88, 319–348 (1989).

Hippensteel, S. P. & Martin, R. E. Foraminifera as an indicator of overwash deposits, Barrier Island sediment supply, and Barrier Island evolution: Folly Island South Carolina. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 149, 115–125 (1999).

Pilarczyk, J. E. et al. Microfossils from coastal environments as indicators of paleo-earthquakes, tsunamis and storms. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 413, 144–157 (2014).

Morton, R. A., Gelfenbaum, G. & Jaffe, B. E. Physical criteria for distinguishing sandy tsunami and storm deposits using modern examples. Sediment. Geol. 200, 184–207 (2007).

Radabaugh, K. R. et al. Mangrove Damage, Delayed Mortality, and Early Recovery Following Hurricane Irma at Two Landfall Sites in Southwest Florida, USA. Estuaries Coasts 43, 1104–1118 (2020).

Parkinson, R. W. & Wdowinski, S. Accelerating sea-level rise and the fate of mangrove plant communities in South Florida, USA. Geomorphology 412, 14 (2022).

Kosciuch, T. J. et al. Foraminifera reveal a shallow nearshore origin for overwash sediments deposited by Tropical Cyclone Pam in Vanuatu (South Pacific). Mar. Geol. 396, 171–185 (2018).

McCloskey, T. A. & Liu, K. A sedimentary-based history of hurricane strikes on the southern Caribbean coast of Nicaragua. Quat. Res. 78, 454–464 (2012).

Goff, J., McFadgen, B. G. & Chagué-Goff, C. Sedimentary differences between the 2002 Easter storm and the 15th-century Okoropunga tsunami, southeastern North Island New Zealand. Mar. Geol. 204, 235–250 (2004).

Ercolani, C., Muller, J., Collins, J., Savarese, M. & Squiccimara, L. Intense Southwest Florida hurricane landfalls over the past 1000 years. Quat. Sci. Rev. 126, 17–25 (2015).

Chmura, G. L. & Aharon, P. Stable carbon isotope signatures of sedimentary carbon in coastal wetlands as indicators of salinity regime. J. Coast. Res.

Lamb, A. L., Wilson, G. P. & Leng, M. J. A review of coastal paleoclimate and relative sea-level reconstrutions using δ13C and C/N ratios in organic material. Earth-Sci. Rev. 75, 29–57 (2006).

Yao, Q. et al. What are the most effective proxies in identifying Storm-Surge deposits in paleotempestology? a quantitative evaluation from the Sand-Liminted, Peat-Dominated Environment of the Florida Coastal Everglades. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 24, 13 (2023).

VDatum. NOAA (2019).

Donato, S. V., Reinhardt, E. G., Boyce, J. I., Pilarczyk, J. E. & Jupp, B. P. Particle=size distribution of inferred tsunami deposits in Sur Lagoon Sultanate of Oman. Mar. Geol. 257, 54–64 (2009).

Blott, S. J. & Pye, K. GRADISTAT: a grain size distribution and statistics package for the analysis of unconsolidated sediments. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 26, 1237–1248 (2001).

Folk, R. L. & Ward, W. C. Brazon River bar: a study in the significance of grain size parameters. J. Sediment. Res. https://doi.org/10.1306/74D70646-2B21-11D7-8648000102C1865D (1957).

Scott, D. B., Medioli, F. S. & Schafer, C. T. Monitoring in Coastal Environments Using Foraminifera and Thecamoebian Indicators. (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Scott, D. B. & Hermelin, J. O. R. A device for precision splitting of micropaleontological samples in liquid suspension. J. Paleontol. 67, 151–154 (1993).

Horton, B. P. & Edwards, R. J. Quantifying holocene sea level change using intertidal foraminifera: lessons from the British Isles. Cushman Found. Foraminifer. Res. Spec. Publ. 40, 97 (2006).

Phleger, F. B. Living Foraminifera from Coastal Marsh Southwestern Florida. Bol. Soc. Geol. Mex. 28, 45–59 (1965).

Todd, R. & Low, D. USGS Professional Paper No 683-C. 36 (1971).

Javaux, E. J. & Scott, D. B. Illustration of modern benthic foraminifera from bermuda and remarks on distribution in other subtropical/tropical areas. Palaeontol. Electron. 6, 29 (1996).

Poag, C. W. Benthic Foraminifera of the Gulf of Mexico: Distribution, Ecology, Paleoecology. (Texas A&M University Press, 2015).

Rabien, K. A. et al. THE FORAMINIFERAL SIGNATURE OF RECENT GULF OF MEXICO HURRICANES. J. Foraminifer. Res. 45, 82–105 (2015).

Balslev-Clausen, D., Dahl, T. W., Saad, N. & Rosing, M. T. Precise and accurate δ13C analysis of rock samples using Flash Combustion-Cavity Ring Down Laser Spectroscopy. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 28, 516–523 (2013).

Lamb, K. & Swart, P. K. The carbon and nitrogen isotopic values of particulate organic material from the Florida Keys: a temporal and spatial study. Coral Reefs 27, 351–362 (2008).

Fourqurean, J. W. & Schrlau, J. E. Changes in nutrient content and stable isotope ratios of C and N during decomposition of seagrasses and mangrove leaves along a nutrient availability gradient in Florida Bay USA. Chem. Ecol. 19, 373–390 (2003).

Plater, A. J., Kirby, J. R., Boyle, J. F., Shaw, T. & Mills, H. Loss on ignition and organic content. In Handbook of Sea-Level Research (eds. Shennan, I., Long, A. J. & Horton, B. P.) 312–330 (John Wiley & Sons, UK, 2015).

Shapiro, S. S. & Wilk, M. B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 52, 591–611 (1965).

Student. The Probable Error of a Mean. Biometrika 6, 1–25 (1908).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020)

ter Braak, C. & Smilauer, P. CANOCO reference manual and user’s guide to Canoco for Windows : software for canonical community ordination (version 4) | Wageningen University and Research Library catalog. (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Casey Craig, Heather Stewart, Fann Yun Toh and Wenshu Yap for their assistance in collecting field data. IH was supported by NSF award RAPID 2308932. JSW was supported by NSF RAPID 2308933. KMJ was supported by the Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund MOE2019-T3-1-004. This work received funding from Villanova University’s Falvey Library Scholarship Open Access Reserve (SOAR) Fund. Site access and research permission were provided by Jay Black for the Ten Thousand Islands National Wildlife Refuge and Karen Rogers for Charlotte Harbor (Florida Department of Environmental protection special use permit 12082214). We thank reviewers Romain Vaucher and Sytze Van Heteren for their helpful reviews and comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IH, KMJ, and JSW conceived and designed the study with input from KRR. IH, KMJ, LN, and KRR conducted field work and sample collection. IH led the execution of sedimentological analyses with contributions from LN. KMJ led and executed foraminifera analysis. JSW led the execution of geochemical analysis with contributions from WB and DCB. IH, KMJ, and JSW wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, I., Joyse, K.M., Walker, J.S. et al. Assessing the preservation potential of successive hurricane overwash deposits in Florida, USA mangroves. Sci Rep 15, 1508 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84083-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84083-y