Abstract

Medical and surgical treatments for cystic echinococcosis (CE) are challenged by various complications. This study evaluates in vitro protoscolicidal activity of piperine-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles (PIP-MSNs) against protoscoleces of Echinococcus granulosus. MSNs were prepared by adding tetraethyl orthosilicate to cetyltrimethylammonium bromide and NaOH, and then loaded with PIP. The mean particle size and hydrodynamic diameter of MSNs were determined at 68 ± 4.5 and 101.4 ± 50.4 nm using transmission electron microscopy and dynamic light scattering, respectively. X-ray diffraction, Fourier-transform infrared analysis, and UV-spectrophotometry confirmed drug loading. Drug loading efficiency and drug loading capacity were calculated at 60% and 18%, respectively. The drug release profile confirmed a 75% PIP release plateau after about 24 h. The cytotoxicity assay showed cell viability > 90% in all concentrations used (≤ 512 µg/mL). E. granulosus protoscoleces were exposed to PIP-MSNs and their viability was assessed using the eosin exclusion test. In a dose-dependent manner (p < 0.001), exposure to 375 and 500 µg/mL of PIP-MSNs for 180 min killed 89.67 and 94.67% of protoscoleces, respectively. This study introduces PIP-MSNs as a potential protoscolicidal agent in the treatment of CE. Further studies are necessary to uncover safety aspects, biodistribution patterns, and potential combination therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Echinococcus granulosus is the causative agent of cystic echinococcosis (CE), a worldwide health problem1. The life cycle of E. granulosus includes a definitive canine host and an intermediate livestock host. Humans may incidentally ingest eggs expelled by definitive hosts via environmental contamination of water and cultivated vegetables or contact with infected domestic dogs2. Infection eventually leads to the formation of a multilayer, fluid-filled cyst containing protoscoleces3. CE is endemic in South America, northern Africa, south-western Asia, the Mediterranean coast, and the Middle East4. As reported by the World Health Organization (WHO), the fragmented data may contribute to an underestimated prevalence of CE in the Eastern Mediterranean Region1, except in Iran, where human seropositivity is reported at 4.2 to 7.4% by meta-analyses5,6,7,8,9.

The infection may remain asymptomatic for many years. Subsequent clinical manifestations and complications depend upon the site and size of the cyst(s), with the liver and lungs being the two most commonly affected organs3. According to the WHO’s diagnostic classification10, current management options for CE may include surgery, percutaneous strategies, medical therapy, and a watch-and-wait approach based on cyst status. Benzimidazole derivatives, such as albendazole and mebendazole, are the drugs of choice for CE pharmacotherapy. Nonetheless, their utility is limited by some adverse effects, particularly hepatotoxicity, bone marrow suppression, and teratogenicity11. In addition, percutaneous strategies (e.g., puncture, aspiration, injection, and re-aspiration [PAIR]) involve the injection of a protoscolicidal agent, most commonly hypertonic saline (20%), into the cyst. Despite the excellent protoscolicidal activity of hypertonic saline, it may cause hypernatremia12 or adjacent tissue damage, such as sclerosing cholangitis2.

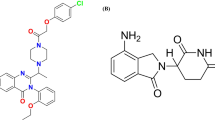

Piperine (PIP), the major bioactive component of Piper nigrum extraction, has attracted considerable interest due to its beneficial medical effects13. Recent studies have addressed various pharmacological activities of this alkaloid compound, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor, antibacterial, and antifungal13. Notably, PIP has shown antiparasitic potential against several species of Plasmodium14, Leishmania15,16, and Trypanosoma17,18,19. Nonetheless, PIP’s therapeutic activities are limited due to its poor water solubility, suboptimal bioavailability, rapid metabolism, and systemic elimination13.

Nanotechnology has dramatically aided in enhancing therapeutic efficiency and improving drug solubility, bioavailability, and release. For instance, the incorporation of PIP into mannose-coated liposomes20 or lipid nanospheres21 was more effective than free PIP in reducing the splenic and hepatic burden of Leishmania donovani. PIP-loaded nano-capsules (PIP-NCs) also exhibited more potent anti-trypanosomal activity against Trypanosoma evansi as compared to free PIP22. Although some previous studies have introduced the protoscolicidal activity of PIP or P. nigrum extractions against E. granulosus23,24, the utility of PIP nanoformulations as protoscolicidal agents has not yet been investigated. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) are proposed as an effective strategy in the design of drug delivery systems due to their larger surface areas, adjustable pore size and volume, acceptable cytotoxicity, and biocompatibility25. In addition, MSNs protect drugs from degradation and immediate release, as well as preserving their properties26. In a recent work27, PIP-loaded modified MSNs were synthesized and evaluated for PIP’s antioxidant and therapeutic properties. This approach used a modified Stöber method to produce nanoparticles with smaller size, optimized morphology, and enhanced stability. These properties highlight the potential of PIP-loaded functionalized MSNs for targeted drug delivery and therapeutic applications. Accordingly, in this study, we aimed to synthesize PIP-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles (PIP-MSNs) and assess their in vitro efficacy as a novel protoscolicidal agent against E. granulosus protoscoleces.

Results

Preparation and characterization of PIP-MSNs

In brief, MSNs were synthesized by preparing a solution of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) in distilled water and sodium hydroxide (NaOH), with sonication and stirring at 80 °C. After the addition of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) and further stirring for 2 h, the precipitate was collected viacentrifugation, washed with deionized water and ethanol, and dried under vacuum. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed for assessment of nanoparticles morphology. As depicted in Fig. 1a, b, TEM images confirmed the spherical morphology and monodispersity of synthesized MSNs. Moreover, the porous morphology of MSNs was also confirmed on TEM images. The estimated size of MSNs using TEM images indicated a mean size of 68 ± 4.5 nm, which was comparable to previous studies28. The hydrodynamic sizes of the prepared particles using dynamic light scattering (DLS) were measured as 101.4 ± 50.4 nm with a polydispersity index (PDI) of 1.34 for MSNs and 302 ± 97.1 nm with a PDI of 0.76 for PIP-MSNs (Fig. 1c, d). Hydrodynamic sizes of the particles measured by DLS are shown to be larger than TEM images, most likely due to the presence of an outer layer of water molecules or the aggregation of particles28,29.

Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometry analysis confirmed the presence of an absorbance peak at 340 nm for PIP-MSNs (Fig. 2c, d), indicating the successful encapsulation of PIP within the MSNs. This characteristic absorbance peak at 340 nm has been previously reported in the literature for PIP, further supporting the successful loading of the drug into the nanoparticle structure30. The dispersion of nanoparticles (NPs) in an aqueous solution in UV-Vis spectrophotometry helps to reduce scattering effects and provides a more accurate spectral measurement31. The low-angle X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of PIP, MSNs, and PIP-MSNs within the 2θ range of 0.5–10° confirmed the successful incorporation of PIP into the MSNs. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, a prominent peak was observed for MSNs at 2θ = 2.09°, whereas PIP alone exhibited no significant peaks in this range. Upon loading PIP into the MSNs, the XRD analysis showed a marked reduction in peak intensity, accompanied by an increase in diffuse scattering for the PIP-MSNs (Fig. 2a). This observation indicates the disruption of the ordered structure and the successful encapsulation of PIP within the MSN framework. Further testing for drug loading was performed using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis. The test provided insights into the functional groups and chemical interactions within the materials studied. The observed peaks correspond to specific vibrations characteristic of chemical bonds present in the samples. The analysis of MSNs revealed peaked vibrations at 454, 801, 962, 1057, 1226, 1480, 2861, and 2926 cm−1. Most of the peaked vibrations observed with MSNs are characteristic of chemical groups containing silica (Si). The peaks near 454, 801, and 1057 cm−1 arise from Si–O–Si, while the peak around 962 is attributed to bending vibrations of Si-OH27.

(a) XRD analysis showing a peak intensity for MSNs and PIP-MSNs at 2θ of 2.09°. (b) FTIR spectroscopy of MSNs, PIP, and PIP-MSNs. (c) UV-Vis spectrophotometry of MSNs and (d) PIP-MSNs. As depicted, PIP-MSNs showed a peak absorbance at 340 nm, comparable to PIP’s maximum absorbance. (e) The cumulative release profile of PIP in PBS (pH 7.4) over 20 h and (f) 72 h. The samples were incubated at 37 °C and 120 rpm (n = 3).

PIP showed peaked vibrations in FTIR analysis at 846, 929, 995, 1252, 1434, 1490, 1584, 1634, and 2941 cm−1. The methylene and methyl groups in the PIP molecule may produce peaks near 2941. Additionally, the peak around 1625 cm−1 and multiple peaks from about 1000 to 1500 indicate the C=C and C–H bending in its aromatic ring27. The PIP-MSN finally showed similar peaked vibrations to PIP and MSNs; however, the prominent peaks were mostly similar to MSNs (Fig. 2b). There may be several reasons for this observation which are explained in the discussion section.

Nanoparticles’ loading capacity and loading efficiency for PIP

The drug loading efficiency (DLE) refers to the percentage of the drug (PIP) successfully incorporated into the MSNs relative to the total amount of drug used in the formulation. DLE was calculated at 60%, according to the formula explained in the methods section for PIP-MSNs. The drug loading capacity (DLC) also represents the amount of drug present in the nanoparticles. The DLC is expressed as the weight percentage of the drug relative to the total weight of the NPs. DLC was calculated at 18% for PIP-MSNs.

In vitro release study

The in vitro release of PIP from MSNs was investigated for 72 h at 37 °C. As depicted in Fig. 2e, f, the cumulative release of PIP from MSNs creates a sustained curve. PIP’s release process from MSNs starts with an initial burst, which releases about 50% of the drug, followed by a slower release rate. After about 24 h, the curve approaches a plateau of approximately 75% (Fig. 2e, f). The initial fraction of the drug, released over the burst phase, likely corresponds to PIP molecules on the MSN surface. On the other hand, it is believed that the slow phase has probably occurred due to the release of PIP molecules existing deep in the pores of MSNs. Over 72 h, 75% of the loaded drug was released into the medium, while the remaining 25% was expected to remain bound to the MSNs (Fig. 2f).

Cytotoxicity properties of PIP-MSNs

The results of the cytotoxicity assay showed over 90% cell viability up to a concentration of 512 µg/mL for MSNs and PIP-MSNs. Control plates (without MSNs or PIP-MSNs) showed 100% viability, indicating the viability of the cells in the absence of any experimental agents. The mean cell viability after 24 h exposure to bare MSNs was 100 ± 1.9% at a concentration of 8 µg/mL. With a slight reduction, 96 ± 2.2% viability was recorded at the maximum concentration of bare MSNs (512 µg/mL). PIP-MSNs were tested for cytotoxicity against L929 fibroblasts and showed a mean cell viability of 100 ± 2% at a concentration of 8 µg/mL. The higher concentrations demonstrated lower cell viability, with 91 ± 2% at a concentration of 512 µg/mL (Fig. 3).

In vitro protoscolicidal activity of PIP-MSNs

The protoscoleces batch with viability of > 90% was used for the in vitro experiments (Fig. 4). The in vitro protoscolicidal activity of different PIP-MSNs concentrations (62.5–500 µg/mL) at various exposure times (5, 10, 20, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min) against protoscoleces of E. granulosus is illustrated in Fig. 5. The differences between the protoscolicidal effects of PIP-MSNs were statistically significant for all concentrations and exposure times (p < 0.001). The minimum protoscolicidal activity of PIP-MSNs was 21.67 ± 2.89% (62.5 µg/mL for 5 min). After 120 min, mortality rates at concentrations of 375 and 500 µg/mL were recorded as 85.33 ± 0.58 and 91.67 ± 1.16%, respectively. A 94.67 ± 1.53% mortality rate was observed at the concentration of 500 µg/mL after 180 min, which was not significantly different from that achieved in the positive control (PC) group (p < 0.001). The maximum concentration of bare MSNs (500 µg/mL) had a relatively minor protoscolicidal activity of 23.00 ± 1.00% after 180 min. All concentrations of PIP-MSNs led to significantly different mortality rates in one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) from those achieved by the negative control (NC) group (p < 0.001). The detailed mortality rates of all groups are provided in the Supplementary Material (Table S1).

Discussion

Natural medicines with fewer adverse reactions and more potent activity has been of interest to researchers for identifying novel protoscolicidal agents24,32,33. Recently, various plant-derived compounds have shown promising protoscolicidal activities against E. granulosus34. PIP is the major alkaloid component of P. nigrum extraction that has been recently considered in medicinal research and has shown promising antiparasitic properties14,15,16,17,18,19. Although studies on parasites and particularly helminths are scarce, PIP killed 40% and 90% of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus juveniles (J2 stage) at concentrations of 30 and 50 µg/mL, respectively35. In addition, all worms were killed after 6 h of exposure to PIP at a concentration of 50 µg/mL. Another study demonstrated that PIP was also active against intracellular amastigotes and axenic epimastigotes of T. cruzi, with 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of 4.91 and 7.36 µM, respectively18. Similarly, in the present study, high mortality rates of 89.67% and 94.67% after 180 min against E. granulosus protoscoleces was recorded using respective concentrations of 375 and 500 µg/mL PIP-MSNs. These concentrations contained approximately 67.5 and 90 µg/mL free PIP, respectively.

Along with protoscolicidal agents, physicians may use systemic anti-E. granulosus medications to reduce cyst size and parasite burden before a surgical intervention or as a single therapy11. Our study showed that although PIP-MSNs were not a rapid protoscolicidal agent, they can kill protoscoleces of E. granulosus up to 94.67% after 180 min. These findings may suggest the potential of PIP-MSNs as an effective antiparasitic medication. Supporting this idea, some studies have addressed the utility of PIP as a systemic antiparasitic agent; nonetheless, evidence on animal and human cases infected with E. granulosus is lacking. In this regard, Khairani et al. showed that oral administration of 40 mg/kg PIP in Plasmodium berghei ANKA-infected mice had excellent prophylactic and curative effects, with a 79.21% and 58.8% reduction in parasitemia, respectively36. Moreover, the administration of PIP significantly improved survival rates and clinical scores.

The exact antiparasitic mechanism of PIP is not well known. Bacterial studies suggest that PIP may act as an inhibitor of efflux pumps37, which are transporter proteins involved in exporting toxic substrate from inside the cells to the external environment. PIP may also inhibit lipid accumulation and suppress the total carbon inflow into the triacylglycerol biosynthesis, leading to a decrease in the lipid body size and cell growth of macrophages and Lipomyces starkeyi37,38,39. Additionally, PIP interacts with the glutamine219 (Gln219) residue of the glutamate-gated chloride ion channel (GluCl) receptor, leading to receptor activation in the parasite Bursaphelenchus xylophilus35. This mechanism was similar to the in-silico effects observed for ivermectin. PIP also induced a reversible cell cycle arrest in T. cruzi epimastigotes, leading to mitochondrion matrix swelling, intense intracellular vacuolization, and impaired cell division17. Furthermore, PIP may potentiate ROS production in the axenic culture of T. evansi22.

A major obstacle to the systemic administration of free PIP, however, is its low water solubility, rapid degradation, and restricted bioavailability13. Nano-based formulations aid in improving the solubility and bioavailability of drugs40,40,42. It has been shown that some organic and inorganic nanoformulations possess antiparasitic properties against E. granulosus protoscoleces. For instance, NPs of several metals, such as gold (Au-NPs, 4 mg/mL) and copper (Cu-NPs, 750 mg/mL), have shown acceptable protoscolicidal activities (76% and 73.3%, respectively) after 60 min of exposure to E. granulosus protoscoleces43,45. Importantly, silver and selenium NPs (Ag-NPs and Se-NPs, respectively) demonstrated excellent protoscolicidal activities. Rahimi et al. showed a 90% mortality rate for Ag-NPs at 0.15 mg/mL concentration after 120 min of exposure to E. granulosus protoscoleces44. Additionally, in a study by Mahmoudvand et al., Se-NPs killed 100% of protoscoleces after 10 min46. It is noteworthy that these metals may exert significant toxicity and adverse effects. In our study, PIP-MSNs at a concentration of 500 µg/mL achieved 94.67% and 91.67% mortality rates against E. granulosus protoscoleces after 120 and 180 min, respectively. Accordingly, it could be hypothesized that nanoformulations containing a combination of PIP with either Ag or Se might exert a more rapid and higher protoscolicidal activity, reducing required doses, exposure time, and possible adverse effects.

In an attempt to improve PIP’s solubility, we successfully synthesized MSNs loaded with PIP. The monodispersity and pore formations were confirmed using TEM images. A recent study also synthesized bare and amine-functionalized MSNs (AAS-MSNPs), with mean sizes of 83 ± 6 nm and 84 ± 2 nm, respectively28. These findings were comparable with the mean size of MSNs in the current work (68 ± 4.5 nm). In addition, the MSNs had sizes of 76 and 114.9 nm in a study by Mohan et al.27. To estimate the size of NPs in their hydrated, functional state in an aqueous system, DLS analysis was performed. DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter of NPs, which includes not only the core size of the particle but also any layers around it, such as solvent molecules or loaded drugs28. We showed a mean hydrodynamic size of 101.4 ± 50.4 nm for MSNs, with similar results from a study by Taebnia et al. (112 ± 8 nm)29.

The MSNs provide a loading bed for appropriate drug delivery and controlled release. We confirmed the drug loading using different methods, including XRD, FTIR, and UV-Vis spectrophotometry. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, XRD analysis of PIP demonstrated a smooth curve without any peak within 2θ of 0.5–10°, while that of MSNs showed a peak intensity at 2θ of 2.09°. After loading PIP into MSNs, the compound filled MSNs’ pores, disrupted their ordered structure, and led to a decrease in XRD peak intensity. Another method for evaluation of the functional groups and chemical interactions within the materials is FTIR. Given the silica-based structure of MSNs, the peaks around 454, 801, and 1057 cm−1 are characteristics of Si–O–Si. These findings are consistent with the results of a previous study on FTIR analysis of MSNs27. Additionally, the peaks near 962 and 1480 cm−1 are due to bending vibrations of Si-OH and C–H, respectively47. We observed peaked vibrations characteristic of different chemical groups in PIP’s molecule, such as peaks around 2941 cm−1 (C–H from methylene and methyl groups), 1634 cm−1 (C=C from aromatic rings), and those from 1000 to 1500 cm−1 (N–H and C–N from piperidine ring)27. Despite confirmation of drug loading by UV-Vis spectrophotometry at 340 nm, in FTIR analysis of PIP-MSNs, most prominent vibrations were similar to MSNs. This could be explained by the fact that PIP accounted for only 18% of the PIP-MSNs’ mass, leading to the attenuation of some PIP’s characteristic vibrations in PIP-MSNs. Moreover, this result may suggest the involvement of some functional groups of PIP in bonding or interactions with the MSNs or confinement of PIP molecules in MSNs’ pores.

While the maximum water solubility of free PIP is 40 µg/mL, we achieved a DLC of 18%. This approach provides a higher available drug concentration with sustained release and probably without the formation of precipitations in aqueous media or blood (in cases of intravenous administration). The DLC refers to the amount of drug present in the nanoparticles. In our study, this index was higher than that reported in a previous study, which demonstrated a DLC of 11% for CUR-MSNs28. However, this difference is possibly due to variations in functional groups of loaded drugs (PIP vs. CUR) or MSNs’ synthesis protocol. Another index, DLE, refers to the percentage of PIP incorporated into the NPs during the loading process. We achieved a DLE of 60% for PIP-MSNs, whereas it was reported at 13.9% for CUR-MSNs28.

Our findings showed cell viabilities more than 90% even at the maximum concentrations (512 µg/mL) of MSNs and PIP-MSNs. Similarly, a negligible (less than 20%) cytotoxic effect for MSNs on rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells was reported by a previous study29. Emerging evidence suggests the possible safety of systemically administered MSNs, particularly via oral and intravenous routes. This is promising as the liver, a primary site of E. granulosus cyst formation, accumulates high levels of MSNs48. Future studies may consider employing PIP-MSNs as a single or adjunct therapy for CE in vivo experiments, examining cyst penetration and therapeutic applications of this agent. Among other nanoformulations of PIP, some studies have investigated their antiparasitic use for systemic administration, although such studies on E. granulosus protoscoleces are lacking. For instance, a single intravenous dose of PIP-containing lipid nanospheres (LN-P, equivalent to 5 mg/kg PIP) reduced the L. donovani burden in the liver and spleen by 63% and 52%, respectively21. Using the pegylated LN-P (LN-P-PEG) formulation, 78% and 75% reductions were achieved in the parasite burden of the liver and spleen, respectively. The most effective formation, however, was LN-P with stearylamine (LN-P-SA), which reduced the parasite burden in the liver and spleen by 90% and 85%, respectively. Notably, intravenous administration of 5 mg/kg PIP, LN-P, LN-PSA, and LN-P-PEG in L. donovani-infected mice did not cause any significant changes in the serum levels of alanine transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, creatinine, or urea compared to the control group.

This study has some limitations. Although the in vitro design of the study confirmed the protoscolicidal activity of PIP-MSNs, future ex vivo and in vivo experiments may consider investigating the potential of PIP-MSNs (alone or in combination with other agents) as an antiparasitic medication, especially when administered through a systemic route. Furthermore, after promising initial investigations, it is essential to perform comprehensive pharmaceutical assessments alongside advanced analyses, such as gas adsorption-desorption studies, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area measurements, and biodistribution evaluations to ensure a thorough understanding of the material’s properties and behavior. The biodistribution of PIP-MSNs, particularly when considered for systemic therapies, should be evaluated through imaging techniques and quantitative biodistribution studies, such as fluorescence or radiolabel tracking. Third, although our in vitro cell viability assay showed acceptable cytotoxicity results, in vivo safety studies focusing on liver and kidney function should be conducted using histopathological examinations and serum biomarker analyses for MSNs and PIP-MSNs. Additionally, previous studies have shown minimal antibacterial activity for unloaded MSNs49, which is consistent with our findings on the parasite E. granulosus. However, the potential synergy between unloaded MSNs and antiparasitic agents, particularly against E. granulosus protoscoleces, remains an underexplored area of research. Finally, further studies should focus on elucidating PIP’s mechanism of action against E. granulosus by employing techniques such as proteomics or transcriptomics. These approaches would help uncover potential pharmacological targets and optimize antiparasitic effects.

Conclusion

In the present study, we successfully synthesized and characterized PIP-MSNs, introducing MSNs as appropriate nanocarriers for PIP loading, drug delivery, and controlled release. We also highlighted the potential of PIP-MSNs as a protoscolicidal agent against the protoscoleces of E. granulosus. The developed PIP-MSNs showed dose-dependent in vitro protoscolicidal activity, with 91.67 and 94.67% mortality rates at a concentration of 500 µg/mL after 120 and 180 min, respectively. Both bare MSNs and PIP-MSNs had minimal cytotoxic activities in the cell viability assay. However, further ex vivo and in vivo studies are warranted. Moreover, PIP’s cellular and molecular targets remain poorly understood, and additional studies to identify these potential pharmacological targets are crucial.

Materials and methods

Materials

PIP (CAS-No: 94-62-2; Sigma-Aldrich; purity ≥ 97%), eosin powder, sodium chloride, ethanol, CTAB, TEOS, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), penicillin-streptomycin (pen/strep), NaOH, dimethyl-sulfoxide (DMSO), and 2,5-diphenyl-2 H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA).

Synthesis of nanoparticles

Preparation of mesoporous silica nanoparticles

MSNs were prepared using reference methods50,51, with some modifications. Briefly, a clear solution of 0.5 g of CTAB in 250 mL of distilled water (DW) and 2 mL of NaOH (2 M) was prepared using sonication and constant stirring at 80 °C. Then, 5 mL of TEOS was slowly added to the final mixture and stirred at 80 °C for another 2 h. The precipitate was separated by centrifugation at 9000 rpm for 15 min. It was then washed with deionized water and absolute ethanol, followed by vacuum drying.

Drug loading

For drug loading, 100 mg of PIP was dissolved in 10 mL of absolute ethanol. With the addition of 1.5 g of MSNs, the solution was stirred in darkness at 24 ± 1 °C for 24 h. After centrifuging the solution at 10,000 rpm for 30 min, the supernatant was collected for a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (with a wavelength of 340 nm) to confirm PIP loading. Finally, the resultant pellet was washed with distilled water repeatedly and dried under vacuum51.

Chemical and structural characterization

The morphology characterization of MSNs was performed using TEM (Philips EM208S 100 kV, Netherlands) and DLS (Nano-ZS90 dynamic light scattering, Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). To determine the structural properties of MSNs and PIP-MSNs, low-angle powder XRD (D8 ADVANCE, Bruker, Germany) with Cu Kα radiation was employed. Diffraction data were recorded between 2θ of 0.5 to 10° with a 2θ resolution of 0.01°. Identification of functional groups in MSNs and PIP was achieved using FTIR (400–4000 cm−1, Vertex 70v, and Tensor II, Bruker, Germany) for confirmation of the successful synthesis of MSNs and PIP-MSNs.

Drug loading efficiency and capacity

UV-Vis spectrophotometry method was employed to determine the loading efficiency and capacity of PIP in MSNs. In brief, a solution of PIP-MSNs in ethanol was prepared and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C for 30 min (Sigma, cold centrifuge, Germany). After washing the pellets twice with 10% aqueous ethanol and drying them under vacuum (50 °C), the optical density (OD) of the collected supernatant was measured at 340 nm30 using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Genesys UV-Vis Spectrophotometer, China). According to the previously performed calibration curves, the concentration of free PIP in the supernatant was then calculated. The DLE and DLC were calculated using the following formulas:

Drug release profile

The amount of PIP released by PIP-MSNs was assessed using a dispersion method. After placing PIP-MSNs in dialysis bags (molecular weight cut-off [MWCO] = 12 kDa) immersed in PBS (pH 7.4), the bags were then shaken for 72 h in the dark (120 rpm and 37 °C). At time intervals, 3 mL samples were withdrawn from each release medium. The PIP concentration in each sample was then measured using UV-spectrophotometry at 340 nm, performed in triplicate. To maintain a steady volume and avoid interruptions in cumulative release, the sampled amount was put back into the release medium after spectrophotometry. Using the calibration curve, the PIP concentration was estimated, and the cumulative release (CR) was calculated as follows:

Cell viability study

The MTT reduction assay was used for in vitro cytotoxicity experiments52. 96-well plates were seeded with L929 fibroblast cells (3 × 104 cells/well) in 100 µL of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with pen/strep (100 units/mL + 100 µg/mL) and 10% FBS. The plates were incubated at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere (95% relative humidity and 5% CO2). After the first 24 h of incubation, the old media were replaced with fresh media containing different concentrations of MSNs and PIP-MSNs (8–512 µg/mL). Following a further 24 h incubation, the media were replaced with fresh media containing 10% MTT (5 mg/mL). The plates were then incubated for an additional 4 h. Finally, the culture media were replaced with 100 µL of DMSO. Using a multi-well assay plate reader (Expert 96, Asys Hitchech, Austria), absorbance values at 570 nm were recorded, and cell viability was calculated as follows:

In vitro protoscolicidal activity

Protoscoleces collection

Protoscoleces of E. granulosus were collected from infected sheep livers slaughtered at the Shiraz slaughterhouse, Fars Province, southern Iran. The preparation protocol and viability assessment of protoscoleces are described in our previous work32.

Protoscolicidal activity

Using serial dilution, five concentrations of PIP-MSNs, including 62.5, 125, 250, 375, and 500 µg/mL, were prepared and exposed to collected protoscoleces for 5, 10, 20, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min. For this purpose, 0.5 mL of each PIP-MSNs concentration was added to 0.5 mL of the protoscoleces solution, containing approximately 2 × 103 parasites/mL. Microwells were then incubated at 37 °C for 5, 10, 20, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min. After removing the supernatant of the mixture, 25 µL of eosin stain (0.1%) was added and gently mixed. Smears of the protoscoleces’ sediment were prepared and studied under light microscopy. PBS solution and hypertonic saline (20%) were used as the NC and PC groups, respectively. A solution of 500 µg/mL unloaded MSNs was also used for controlling the protoscolicidal effects of bare MSNs. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Viability assay

The viability of the protoscoleces was assessed using a light microscope to determine their flame cell motility and permeability to a 0.1% eosin solution53. Dead protoscoleces are immobile and permeable to eosin (red). In contrast, live protoscoleces are mobile and do not absorb eosin (colorless). The mortality rates of the protoscoleces were calculated as the proportion of dead to total protoscoleces.

Statistical analysis

R software version 4.3.0 (R Core Team, Austria) was used for statistical analyses. The mortality rates of the protoscoleces were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). A one-way ANOVA was performed, followed by a Games-Howell multiple comparisons test to assess statistical differences between the experimental groups. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed in this research are included within the manuscript and supplementary material.

References

World Health Organization. Global Report on Neglected Tropical Diseases 2023 (2023).

Wen, H. et al. Echinococcosis: advances in the 21st century. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 32, 1 (2019).

Romig, T., Zeyhle, E., Macpherson, C. N., Rees, P. H. & Were, J. B. Cyst growth and spontaneous cure in hydatid disease. Lancet 1, 861 (1986).

Hogea, M. O. et al. Cystic echinococcosis in the early 2020s: a review. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 9, 1 (2024).

Galeh, T. M. et al. The seroprevalence rate and population genetic structure of human cystic echinococcosis in the Middle East: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 51, 39–48 (2018).

Khalkhali, H. R. et al. Prevalence of cystic echinococcosis in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Helminthol. 92, 260–268 (2018).

Mahmoudi, S., Mamishi, S., Banar, M., Pourakbari, B. & Keshavarz, H. Epidemiology of echinococcosis in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 929 (2019).

Shafiei, R. et al. The seroprevalence of human cystic echinococcosis in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. J. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 1425147 (2016).

Tian, T., Miao, L., Wang, W. & Zhou, X. Global, Regional and National Burden of Human Cystic Echinococcosis from 1990 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 9, 1 (2024).

International classification of. Ultrasound images in cystic echinococcosis for application in clinical and field epidemiological settings. Acta Trop. 85, 253–261 (2003).

Junghanss, T., Da Silva, A. M., Horton, J., Chiodini, P. L. & Brunetti, E. Clinical management of cystic echinococcosis: state of the art, problems, and perspectives. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 79, 301–311 (2008).

Zeng, R., Wu, R., Lv, Q., Tong, N. & Zhang, Y. The association of hypernatremia and hypertonic saline irrigation in hepatic hydatid cysts: a case report and retrospective study. Medicine (Baltim.) 96, e7889 (2017).

Gorgani, L., Mohammadi, M., Najafpour, G. D. & Nikzad, M. Piperine—the bioactive compound of black pepper: from isolation to medicinal formulations. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 16, 124–140 (2017).

Khairani, S. et al. The potential use of a curcumin-piperine combination as an antimalarial agent: A systematic review. J. Trop. Med. 9135617 (2021).

Ferreira, C. et al. Leishmanicidal effects of piperine, its derivatives, and analogues on Leishmania amazonensis. Phytochemistry 72, 2155–2164 (2011).

Sharifi, F., Mohamadi, N., Afgar, A. & Oliaee, R. T. Anti-leishmanial, immunomodulatory and additive potential effect of piperine on Leishmania major: the in silico and in vitro study of piperine and its combination. Exp. Parasitol. 254, 108607 (2023).

Freire-de-Lima, L. et al. The toxic effects of piperine against Trypanosoma cruzi: ultrastructural alterations and reversible blockage of cytokinesis in epimastigote forms. Parasitol. Res. 102, 1059–1067 (2008).

Ribeiro, T. S. et al. Toxic effects of natural piperine and its derivatives on epimastigotes and amastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 14, 3555–3558 (2004).

Shaba, P. O., Pandey, N. N., Sharma, O. P., Rao, J. R. & Singh, R. Anti-trypanosomal activity of Piper nigrum L. (Black pepper) against Trypanosoma evansi. J. Vet. Adv. 2, 161–167 (2012).

Raay, B., Medda, S., Mukhopadhyay, S. & Basu, M. K. Targeting of piperine intercalated in mannose-coated liposomes in experimental leishmaniasis. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 36, 248–251 (1999).

Veerareddy, P. R., Vobalaboina, V. & Nahid, A. Formulation and evaluation of oil-in-water emulsions of piperine in visceral leishmaniasis. Pharmazie 59, 194–197 (2004).

Rani, R., Kumar, S., Dilbaghi, N. & Kumar, R. Nanotechnology enabled the enhancement of antitrypanosomal activity of piperine against Trypanosoma evansi. Exp. Parasitol. 219, 108018 (2020).

Cheraghipour, K. et al. In vitro potential effect of Pipper longum methanolic extract against protoscolices of hydatid cysts. Exp. Parasitol. 221, 108051 (2021).

Dakllaoe, H. A., Al-Hilfi, A. A. A. & Almansour, N. A. A. The effect of piperine and curcumin on the calmodulin gene of Echinococcus granulosus protoscolices in vitro. Iran. J. Ichthyol. 8, 317–329 (2021).

Manzano, M. & Vallet-Regí, M. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1902634 (2020).

Lu, J., Liong, M., Li, Z., Zink, J. I. & Tamanoi, F. Biocompatibility, biodistribution, and drug-delivery efficiency of mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cancer therapy in animals. Small 6, 1794–1805 (2010).

Mohan, S. & Thankaswamy, J. Synthesis and characterization of piperine-modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 1, 1 (2024).

Taebnia, N. et al. Curcumin-loaded amine-functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles inhibit α-synuclein fibrillation and reduce its cytotoxicity-associated effects. Langmuir 32, 13394–13402 (2016).

Taebnia, N. et al. The effect of mesoporous silica nanoparticle surface chemistry and concentration on the α-synuclein fibrillation. RSC Adv. 5, 60966–60974 (2015).

Kusumorini, N., Nugroho, A. K., Pramono, S. & Martien, R. Development of new isolation and quantification method of piperine from white pepper seeds (Piper nigrum L.) using a validated HPLC. Indones. J. Pharm. 1, 158–165 (2021).

Passos, L. C., Saraiva, M. F. S. & M. & Detection in UV-visible spectrophotometry: detectors, detection systems, and detection strategies. Measurement 135, 896–904 (2019).

Teimouri, A. et al. Protoscolicidal effects of curcumin nanoemulsion against protoscoleces of Echinococcus granulosus. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 23, 124 (2023).

Albalawi, A. E., Shater, A. F., Alanazi, A. D., Alsulami, M. N. & Almohammed, H. I. High potency of linalool-zinc oxide nanocomposite as a new agent for cystic echinococcosis treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. e0173423 (2024).

Ali, R. et al. A systematic review of medicinal plants used against Echinococcus granulosus. PLoS One 15, e0240456 (2020).

Rajasekharan, S. K., Raorane, C. J. & Lee, J. Nematicidal effects of piperine on the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. J. Asia Pac. Entomol. 23, 863–868 (2020).

Khairani, S. et al. Oral administration of piperine as curative and prophylaxis reduces parasitaemia in Plasmodium berghei ANKA-infected mice. J. Trop. Med. 5721449 (2022).

Mirza, Z. M., Kumar, A., Kalia, N. P., Zargar, A. & Khan, I. A. Piperine as an inhibitor of the MdeA efflux pump of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Med. Microbiol. 60, 1472–1478 (2011).

Kimura, K., Yamaoka, M. & Kamisaka, Y. Inhibition of lipid accumulation and lipid body formation in oleaginous yeast by effective components in spices, carvacrol, eugenol, thymol, and piperine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 54, 3528–3534 (2006).

Matsuda, D., et al. Molecular target of piperine in the inhibition of lipid droplet accumulation in macrophages. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 31, 1063–1066 (2008).

Azami, S. J. et al. Curcumin nanoemulsion as a novel chemical for the treatment of acute and chronic toxoplasmosis in mice. Int. J. Nanomed. 13, 7363–7374 (2018).

Teimouri, A. et al. Anti-Toxoplasma activity of various molecular weights and concentrations of chitosan nanoparticles on tachyzoites of RH strain. Int. J. Nanomed. 13, 1341–1351 (2018).

Sahebi, K. et al. In vitro and in vivo anti-parasitic activity of curcumin nanoemulsion on Leishmania major (MRHO/IR/75/ER). BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 24, 238 (2024).

Napooni, S., Arbabi, M., Delavari, M., Hooshyar, H. & Rasti, S. Lethal effects of gold nanoparticles on protoscolices of hydatid cyst: in vitro study. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 28, 143–150 (2019).

Rahimi, M. T. et al. Scolicidal activity of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles against Echinococcus granulosus protoscolices. Int. J. Surg. 19, 128–133 (2015).

Ezzatkhah, F., Khalaf, A.K. & Mahmoudvand, H. Copper nanoparticles: Biosynthesis, characterization, and protoscolicidal effects alone and combined with albendazole against hydatid cyst protoscoleces. Biomedicine Pharmacotherapy 136, 111257 (2021).

Mahmoudvand, H. et al. Scolicidal effects of biogenic selenium nanoparticles against protoscolices of hydatid cysts. Int. J. Surg. 12, 399–403 (2014).

de Oliveira, L. F. et al. Functionalized silica nanoparticles as an alternative platform for targeted drug-delivery of water insoluble drugs. Langmuir 32, 3217–3225 (2016).

Fu, C. et al. The absorption, distribution, excretion and toxicity of mesoporous silica nanoparticles in mice following different exposure routes. Biomaterials 34, 2565–2575 (2013).

Alandiyjany, M. N. et al. Novel in vivo assessment of antimicrobial efficacy of ciprofloxacin loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles against Salmonella typhimurium infection. Pharmaceuticals 15, 357 (2022).

Altememy, D., Jafari, M., Naeini, K., Alsamarrai, S. & Khosravian, P. In-vitro evaluation of metronidazole loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles against Trichomonas vaginalis. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Scholars 12, 2773 (2021).

Kuang, G., Zhang, Q., He, S. & Liu, Y. Curcumin-loaded PEGylated mesoporous silica nanoparticles for effective photodynamic therapy. RSC Adv. 10, 24624–24630 (2020).

Tolosa, L., Donato, M. T. & Gómez-Lechón, M. J. General cytotoxicity assessment by means of the MTT assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 1250, 333–348 (2015).

Karpisheh, E., Sadjjadi, S. M., Nekooeian, A. A. & Sharifi, Y. Evaluation of structural changes of Echinococcus granulosus protoscoleces following exposure to different protoscolicidal solutions evaluated by differential interference contrast microscopy. J. Parasit. Dis. 47, 850–858 (2023).

Funding

This research was financially supported by the office of the vice-chancellor for research at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (project code: 27656).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S., A.T. and E.M. conceived and designed the study. K.S. and S.T. were involved in the synthesis and characterization of NPs. The parasitological experiments were carried out by K.S., H.F., M.A., A.T., and Y.S. Data analysis was performed by K.S., A.T., and R.A. K.S., A.T., and E.M. prepared the original draft paper. A.T., E.M., Z.Z., and SM.S. reviewed and edited the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sahebi, K., Takallu, S., Foroozand, H. et al. Piperine-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a promising strategy for targeting Echinococcus granulosus protoscoleces. Sci Rep 15, 520 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84131-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84131-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Linalool as a potential agent against Toxoplasma gondii: an in vitro study

BMC Research Notes (2025)