Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen responsible for various infections in humans and animals. It is known for its resistance to multiple antibiotics, particularly through the production of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases (ESBLs), and its ability to form biofilms that further complicate treatment. This study aimed to isolate and identify K. pneumoniae from animal and environmental samples and assess commercial disinfectants’ effectiveness against K. pneumoniae isolates exhibiting ESBL-mediated resistance and biofilm-forming ability in poultry and equine farms in Giza Governorate, Egypt. A total of 320 samples, including nasal swabs from equine (n = 60) and broiler chickens (n = 90), environmental samples (n = 140), and human hand swabs (n = 30), were collected. K. pneumoniae was isolated using lactose broth enrichment and MacConkey agar, with molecular confirmation via PCR targeting the gyrA and magA genes. PCR also identified ESBL genes (blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, blaOXA-1) and biofilm genes (luxS, Uge, mrkD). Antimicrobial susceptibility was assessed, and the efficacy of five commercial disinfectants was evaluated by measuring inhibition zones. Klebsiella pneumoniae was isolated from poultry (13.3%), equine (8.3%), wild birds (15%), water (10%), feed (2%), and human hand swabs (6.6%). ESBL and biofilm genes were detected in the majority of the isolates, with significant phenotypic resistance to multiple antibiotics. The disinfectants containing peracetic acid and hydrogen peroxide were the most effective, producing the largest inhibition zones, while disinfectants based on sodium hypochlorite and isopropanol showed lower efficacy. Statistical analysis revealed significant differences in the effectiveness of disinfectants against K. pneumoniae isolates across various sample origins (P < 0.05). The presence of K. pneumoniae in animal and environmental sources, along with the high prevalence of ESBL-mediated resistance and biofilm-associated virulence genes, underscores the zoonotic potential of this pathogen. The study demonstrated that disinfectants containing peracetic acid and hydrogen peroxide are highly effective against ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae. Implementing appropriate biosecurity measures, including the use of effective disinfectants, is essential for controlling the spread of resistant pathogens in farm environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a significant pathogen affecting both animal and human health. In humans, K. pneumoniae is a leading bacteria responsible for nosocomial infections, contributing to serious conditions such as pneumonia1. It can lead to severe respiratory issues and increased mortality in poultry, especially in crowded environments2. Additionally, in equines, this bacterium can cause respiratory symptoms like hemorrhagic nasal discharge and pneumonia, and it has also been linked to abortion in pregnant mares3,4.

K. pneumoniae is notorious for acquiring beta-lactam resistance genes, including extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), which pose serious treatment challenges and increase healthcare costs5,6. These strains resist a broad range of beta-lactam antibiotics, including penicillins and cephalosporins. ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains present a particularly significant challenge due to their resistance mechanisms and potential for horizontal gene transfer7.

Wild birds serve as reservoirs, shedding the bacterium into the environment, which can lead to contamination of water sources and subsequent transmission to humans and animals8,9. K. pneumoniae contamination in water sources poses significant public health risks, particularly through pathways such as agricultural runoff, sewage discharge, and animal feces10,11. Contaminated water can transmit the bacterium to humans and animals, especially in vulnerable populations lacking adequate sanitation. Several studies have suggested that microbes form biofilms in poultry water systems12,13. Notably, K. pneumoniae strains in water may carry antibiotic resistance and virulence genes, posing a risk of spreading these traits to other pathogens14.

Biofilms are bacterial communities composed of one or more species embedded within an extracellular matrix made of polysaccharides, proteins, and DNA. Their formation enhances the bacterium’s resistance to antimicrobial agents and external stressors, playing a pivotal role in its pathogenicity15. For K. pneumoniae, biofilms serve as a key virulence mechanism, offering increased environmental resilience and acting as reservoirs for genetic exchange, thereby promoting the spread of antimicrobial resistance16.

Studies have identified numerous genes associated with biofilm formation, including those involved in the production of aerobactin (iutA), allantoin (allS), type I fimbriae (fimA and fimH), type III fimbriae (mrkA and mrkD), capsular polysaccharides (CPS) (cpsD, treC, wabG, wcaG, wzc, k2A, and wzyK2), quorum sensing (QS) (luxS), and colonic acid (wcaJ)17,18,19. Moreover, the uge gene, which encodes UDP-galacturonate 4-epimerase crucial for LPS biosynthesis, supports biofilm formation by maintaining cell surface integrity, aiding initial adhesion, and enhancing protection within the biofilm20,21.

Recent evidence indicates that biofilm formation is significantly more prevalent in ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains, suggesting that therapeutic guidelines should incorporate the impact of biofilm production when optimizing treatment strategies and clinical outcomes, rather than relying solely on antibiotic susceptibility test results, as these biofilms can protect bacteria from both antimicrobial agents and immune defenses22,23.

The genetic diversity among clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae, including variations in virulence and resistance genes, underscores the challenge of managing infections caused by this pathogen14,24. Understanding the mechanisms behind genetic diversity in K. pneumoniae, including specific virulence and resistance genes, their interactions, and their contributions to the pathogen’s overall virulence, is crucial for developing effective strategies to combat biofilm-associated infections, improve patient outcomes, and ultimately lead to new therapeutic approaches for managing and treating these infections25,26.

Biocides have long been used to reduce microbial populations on various surfaces, serving as a key tool in preventing the proliferation of multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms and the transmission of infections27. According to the European Commission, a “biocidal product” is defined as a substance that contains one or more active ingredients or facilitates their formation, and is designed to "destroy, deter, or render harmless" microorganisms through non-physical or non-mechanical means to mitigate or eliminate potential adverse effects on host health28. These compounds are typically categorized into four groups based on their primary characteristics and mode of action: antiseptics, sterilants, disinfectants, and preservatives29,30. A lack of adequate information regarding sanitation programs hinders effective regulation and control of zoonotic disease spread, thereby increasing health risks for both animals and farmers31. Farms implement sanitary measures such as spraying disinfectants in sheds and removing feces32.

According to Stringfellow et al.32 the farms implemented sanitation protocols, including disinfectants in shelters and removing feces. Disinfectants are frequently implemented according to the manufacturing guide. Nevertheless, the efficacy of disinfectants can be influenced by various factors, including the degree of organic burden, humidity, temperature, dilution rate, pH, and water hardness. Furthermore, the use of disinfectants without adequate validation and evaluation can lead to a substantial increase in selective pressure, which in turn results in a progressive decrease in the sensitivity of organisms to the disinfectants used. This can result in cross-resistance, in which the organisms develop resistance to antibiotics that are significant to public health33.

Despite the recognized role of biofilm formation in K. pneumoniae virulence and spread, there is a notable gap in understanding the prevalence of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae and its association with biofilm-related genes in livestock, particularly poultry, and equine. This study aims to characterize K. pneumoniae in livestock, their environments, and workers, focusing on biofilm formation, antibiotic resistance, ESBL genes, and genetic diversity. Additionally, it evaluates the effectiveness of five disinfectants as biosecurity measures to reduce infection risks in humans and animals.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and preparation

A total of 320 samples were collected between June 2022 and April 2023 from eight farms in Giza Governorate, Egypt, where poultry and equines were affected by respiratory infections. These included 150 nasal swabs from animals with respiratory illness (60 from equines and 90 from broiler chickens), 140 environmental samples, and 30 hand swabs from farm workers. Among the farms, three were poultry farms, and five were equine farms. All samples were analyzed for the presence of K. pneumoniae.

The nasal and hand swabs were collected using sterile swabs, with nasal samples placed in 2 mL of sterile saline (0.9% NaCl) and hand swabs in 9 mL of sterile buffered peptone water (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England).

Environmental samples included 50 livestock drinking water samples (30 from equine water troughs and 20 from poultry drinking sources), 50 feed samples collected from animal pens, and 40 fecal samples from wild birds (10 crows, 10 pigeons, and 20 laughing doves).

Wild birds were captured using mist nets set up for six hours in farm areas and checked every 20 min to identify and mark birds to prevent resampling. Fresh fecal samples from the captured birds were collected using sterile cotton swabs and stored in 15-mL polyethylene tubes.

All samples, including drinking water collected in sterile 1-L glass bottles and feed samples in sterilized bags, were transported to the laboratory in an icebox at 4 °C for microbiological analysis.

Isolation and identification of K. Pneumoniae

Each sample was inoculated into lactose broth (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Following enrichment, a loopful of the broth was streaked onto MacConkey agar (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK) and incubated at 37 °C for 18–24 h. To isolate Klebsiella species from the water samples, the membrane filtration technique was employed. For this process, 100 mL of each water sample was filtered through a sterile 0.45-µm pore-size membrane filter. The filters were then aseptically transferred onto the surface of MacConkey agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for 18–24 h.

Suspected Klebsiella spp. colonies were selected according to Collee et al.34 and subcultured to obtain pure cultures. To address the limitations of relying solely on colony morphology on MacConkey agar and to ensure accurate identification, the pure culture was subjected to a series of conventional biochemical tests, including catalase, oxidase, oxidative-fermentative, indole, methyl red, Voges-Proskauer, citrate, and triple sugar iron agar tests35. All reagents used for these biochemical tests were sourced from Oxoid (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK).

Molecular confirmation of K. Pneumoniae isolates and detection of ESBL-mediated resistance and biofilm genes

Extraction of the genomic DNA

Two milliliters of enriched lactose broth were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. After discarding the supernatant, 200 µL of nuclease-free water was added to the pellet. The pellet was dissolved and heated in a water bath at 100 °C for 10 min, then cooled to 20 °C and left overnight. The mixture was centrifuged again at 13,000 rpm for 10 min, and the resulting supernatant was used as the DNA template for all PCR reactions36. The extracted DNA was stored at -20 °C for future use.

Molecular confirmation of Klebsiella spp. and K. pneumoniae isolates

Klebsiella isolates were confirmed by amplifying the gyrA gene specific to the Klebsiella genus, as previously described37. For the specific identification of K. pneumoniae, the magA primer was utilized37. Details of the primer sequences, amplicon sizes, and amplification conditions for both the gyrA gene and magA gene are provided in Table 1.

Molecular detection of ESBL encoding genes

All strains confirmed as K. pneumoniae were further screened for relevant ESBL-encoding resistance genes using multiplex PCR as previously described38,39. This PCR targeted blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, and blaOXA-1 resistance determinant genes using specific oligonucleotide primer sets (Table 1). The PCR reaction was performed in a total volume of 25 µl, consisting of 3 µl of template DNA from each isolate, 12.5 µl of EmeraldAmp MAX PCR master mix (Takara, Japan), 0.5 µl of each primer (10 pmol/µl; Metabion, Germany), and PCR-grade water to complete the volume. Details of the primer sequences and amplification conditions are provided in Table 1.

All PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel (vivantis, Malysia) and visualized under a UV transilluminator. A 100 bp DNA ladder (Jenna Bioscience GmbH, Jenna, Germany) was run alongside the samples to determine the size of the PCR amplicon. A negative control, which included all PCR components except water instead of template DNA, was also included. The positive control consisted of the E. coli strain ATCC 25922.

Molecular detection of the biofilm genes

Uniplex PCR was performed on K. pneumoniae isolates to detect the biofilm genes (luxS, Uge, and mrkD). The reaction was performed according to Arafa and Kandil22. The primer sequences, amplification conditions, and amplicon sizes are presented in Table 1. Positive control was included in each set of reactions and the negative control was nuclease-free water that replaced the DNA sample in the PCR mix. The PCR products (S1–S3) were seen on 1.5% agarose gels.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test of selected ESBL-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates harboring biofilm-associated genes

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted on 18 selected K. pneumoniae isolates from various sources, exhibiting ESBL resistance and biofilm-associated genes, using the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method on Mueller–Hinton agar (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK). A total of 14 antimicrobial agents were tested, including gentamycin(GEN:10 µg), ampicillin (AMP: 10 µg), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (AMC: 30 µg), erythromycin (ERY: 15 µg), Azithroyn (AZM: 30 µg), cefotaxime (CTX: 30 µg), Ceftazidime (CAZ:30 µg), nalidixic acid (NAL: 30 µg), ciprofloxacin (CIP: 5 µg), norfloxacin(NOR: 5 µg), chloramphenicol (CHL: 30 µg), tetracycline (TET: 30 µg), ceftriaxone (CT: 30 µg), and Clindamycin (CLN:2 µg ) (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK). The interpretation of inhibition zone diameters was based on the recommendations of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)40. Isolates were classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR) if resistant to 3 different antimicrobial classes41.

Effects of different disinfectants on ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates harboring biofilm-associated genes

Selection of disinfectants

Five commercial disinfectants were prepared and utilized according to the manufacturer’s instructions at ready-to-use concentrations. Disinfectant A contained potassium peroxy-monosulfate and sodium hypochlorite with 1.1% active chlorine (Antec International TD, USA), disinfectant B comprised peracetic acid and hydrogen peroxide at 1.5% (Egy-Holland, Egypt), disinfectant C included a mix of 17.2% isopropanol and 0.28% ammonium compounds (IACs). Disinfectant D was formulated with quaternary ammonium compounds (Fluka Analytical, St. Louis, USA). Finally, Disinfectant E combined quaternary ammonium compounds, glutaraldehyde, formaldehyde, isopropanol, and pine oil (AdvaCare Pharma, USA). Each disinfectant was appropriately diluted per the manufacturer’s guidelines to achieve effective ready-to-use concentrations.

Efficacy testing of disinfectant

The Sixteen Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates selected from animal origin (Equine, poultry, and environment) were inoculated onto Petri plates containing brain–heart infusion agar (BHIA, France) to ensure their purity and vitality. A single colony from each isolate was subcultured on triple sugar iron agar (TSI, Italy) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, followed by an additional 24-h incubation at 36 °C ± 1 °C. The microorganisms were then suspended in a sterile saline solution to achieve a final concentration of 0.5 McFarland (1.5 × 108 colony-forming units/ml) and evenly spread onto Mueller–Hinton agar (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK) using the rolling technique and sterile swabs. Six 7-mm wells were created in the agar: one in the center and five others approximately 20 mm away from the center, establishing the agar diffusion test setup. Each well was filled with 50 μL of a different disinfectant, and the plates were incubated overnight to determine the inhibition zones. The efficacy of each disinfectant was assessed by measuring the diameter of the microbial inhibition zones around the wells. Bacteria were considered sensitive if the inhibitory zone diameter exceeded 8 mm. The tests were conducted in triplicate, and the results were evaluated accordingly. A well containing 50 μL of sterile saline served as a negative control. All experiments were conducted using sterile techniques42,43.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 18.0, with a p-value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant. Chi-square testing was used to compare multiple groups of categorical samples.

Isolates from various sources were grouped based on their antimicrobial resistance (AMR) traits using a heatmap with hierarchical clustering, generated with the “Heatmap” R package (version 4.2.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Clustering of strains was performed using the pheatmap library (version 1.0.12)44.

Results

Occurrence of K. Pneumoniae isolates among different studied isolates

Out of 320 samples, 67 (20.9%) were positive for Klebsiella spp and 31 (9.7%) were positive for K. pneumoniae. Statistical analysis revealed significant variation among sources for the number of Klebsiella spp. positive samples (X2 = 12.171, P = 0.016).

From poultry, 90 samples were examined, with 30 (33.3%) positive for Klebsiella spp. and 12 (13.3%) for K. pneumoniae. Equine samples, totaling 60, had 9 (15%) positive for Klebsiella spp. and 8 (8.3%) for K. pneumoniae. Wild bird samples (40) showed 8 (20%) positive for Klebsiella spp. and 6 (15%) for K. pneumoniae. Water samples (50) yielded 12 (24%) positive for Klebsiella spp. and 5 (10%) for K. pneumoniae. Feed samples (50) had 4 (8%) positive for Klebsiella spp. and 1 (2%) for K. pneumoniae. Human hand swab samples (30) showed 4 (13.3%) positive for Klebsiella spp. and 2 (6.6%) for K. pneumoniae.

Occurrence of ESBL-mediated resistance and biofilm genes in K. Pneumoniae isolates

The frequency and variation of ESBL-mediated resistance in K. pneumoniae isolates and biofilm-associated genes obtained from different animal sources and environments were displayed in the Table 2.

Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences for the individual genes blaTEM (X2 = 3.644, P = 0.302), blaSHV (X2 = 1.296, P = 0.861), blaCTX-M (X2 = 1.241, P = 0.619), Uge (X2 = 1.194, P = 0.769), mrkD (X2 = 1.098, P = 0.7775), and luxS (X2 = 1.458, P = 0.691).

Table 3 presents the pattern of biomarker resistance genes and biofilm-associated genes in selected ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates harboring biofilm-associated genes. Isolates from poultry sources exhibited notable diversity, with two carrying the complete set of resistance genes (blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, blaOXA-1) and biofilm-associated genes (Uge, mrkD, luxS). Similarly, equine sources contributed four isolates with a comparable profile, all possessing blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, and the biofilm-associated genes Uge, mrkD, and luxS.

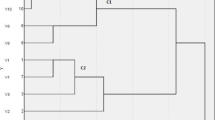

Wild bird isolates were diverse, including one isolate containing the full set of resistance and biofilm genes, which was identified on an equine farm. Water samples, however, displayed consistency, with all three isolates from equine and poultry farms harboring blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, and the biofilm-associated genes Uge, mrkD, and luxS. Human-derived isolates were variable, with one isolate carrying only blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, and Uge, while another had blaTEM, blaSHV, and Uge. The antibiotic resistance profiles of selected isolates recovered from Poultry, Equine, Human, and Environmental Samples, across different antibiotic classes, were displayed in Table 4 and Fig. 1.

A heatmap with hierarchical clustering was generated using R packages to visualize ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates carrying biofilm-associated genes. The isolates were grouped into clusters C1 and C2 based on their phenotypic resistance profiles, while the top of the heatmap (G1 and G2) illustrates the patterns of antibiotic resistance.

The effects of different disinfectants on ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates harboring biofilm-associated genes

Table 5 shows the sizes of the inhibition zones generated by the different disinfectants. The product based on sodium hypochlorite and containing peracetic acid and hydrogen peroxide was significantly more active (p < 0.05) on all K. pneumoniae strains. We observed no significant differences between the different strains of K. pneumoniae when using disinfectant E (p > 0.05). On the other hand, the results in Fig. 2 show that among different K. pneumoniae isolates, poultry and water had the highest readings for the inhibition zone. In contrast, diseased equine had the lowest inhibition zone. In addition, disinfectant B, followed by disinfectant C, had the highest reading for the inhibition zone. Disinfectants based on peracetic acid and hydrogen peroxide were much more effective against K. pneumoniae isolates than disinfectant (A), which had the lowest inhibition zone (p < 0.001).

Discussion

Klebsiella pneumoniae is recognized as a significant pathogen in both nosocomial and community-acquired infections45. While it typically resides in the respiratory tract and intestines of healthy individuals, it has the potential to cause severe infections in various tissues and organs, including pneumonia, meningitis, liver abscesses, urinary infections, and sepsis46. This study highlights the prevalence of K. pneumoniae in both animals and environmental samples, demonstrating its widespread presence. K. pneumoniae was detected in poultry, equine, and wild bird samples, with a notable presence in avian species. It was also identified in environmental sources like water and feed and human hand swabs. Given its ubiquity and pathogenic potential in humans and animals, K. pneumoniae has attracted significant global attention from researchers1. The pathogen accounts for approximately 14–20% of infections in the respiratory tract, biliary duct, surgical wounds, and urinary tract47. These findings underscore the importance of monitoring and controlling K. pneumoniae across various environments to mitigate its impact on public and animal health.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is well-known for its ability to form biofilms, a critical virulence factor that enhances its antibiotic resistance and shields it from immune responses, thereby increasing its persistence in clinical environments48,49. Biofilms are composed of a matrix of polysaccharides, extracellular DNA, and proteins, that protect the bacteria and limit antibiotic penetration, contributing to its resistance15,50. Most Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates exhibit strong biofilm-forming capabilities, which are closely associated with extensive virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes51.

In this study, all Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates tested positive for the uge gene. Specifically, isolates came from poultry, equines, wild birds, water, feed, and human samples. In comparison, most isolates were positive for the mrkD gene and the luxS gene. These results are consistent with findings from Arafa and Kandil22, who reported that K. pneumoniae isolates from equines were positive for uge and luxS. Similarly, Hamam et al.52 found that K. pneumoniae isolates from urinary tract infections carried uge gene.

Studies from different regions reveal varying gene prevalence. Elmeslemany and Yonis53 identified the uge gene in ducklings. In Brazil, Davies et al.54 detected both the uge and mrkD genes in wild bird isolates. Similarly, Daehre et al.55 in Germany and Ferreira et al.56 in Brazil found widespread mrkD gene in broiler chickens and ICU isolates. In Malaysia, Barati et al.57 found the uge gene in water isolates.

Conversely, Ashwath et al.19 observed a reduction in mrkA and mrkD gene expression in K. pneumoniae from clinical specimens, with expression levels varying among strong and moderate biofilm formers. In Iraq, Muhsin et al.58 noted the presence of the mrkD gene in clinical and environmental isolates, indicating regional differences in gene prevalence.

In recent years, with the wide application of antibiotics, the resistance of clinically isolated K. pneumoniae has become stronger and stronger. K. pneumoniae that produce extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBLs) have been observed and introduced significant challenges to antibiosis59.

All Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates tested positive for the blaTEM and blaSHV genes, with most also harboring the blaCTX-M gene. The blaOXA-1 gene was less commonly detected, found in a few isolates from poultry and wild birds. These findings are consistent with those of Arafa et al.5, who reported the presence of the blaTEM gene in equine isolates in Egypt, while blaSHV and blaCTX-M genes were not detected. Regional variations in the prevalence of resistance genes have been noted. For example, Siqueira et al.60 characterized antimicrobial resistance in K. pneumoniae isolates from dogs and a horse in Brazil, identifying multiple ESBL genes, including blaCTX-M, blaTEM, and blaSHV..

The detection of blaTEM and blaSHV genes in K. pneumoniae isolates from different sources, including animals and the environment, underscores the significant role of these genes in antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Recent research highlights the increasing concern over the transmission of antibiotic-resistant genes between domestic animals and their owners, emphasizing the zoonotic potential of resistant bacteria61,62. This underscores the need for vigilant monitoring and control measures to manage the spread of antibiotic resistance.

As observed in this study, the coexistence of multiple ESBL genes with biofilm genes within the same strain indicates a significant potential for gene transfer, which plays a role in the spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). This observation is further supported by the findings of Elmeslemany and Yonis53 and other researchers, who emphasized the link between integrons and ESBL genes, suggesting that these genes may be located on the same plasmid.

The increased prevalence of multidrug-resistant pathogens poses significant challenges in treating bacterial infections, largely attributed to the misuse of antimicrobials in both healthcare settings and communities. These findings highlight the need for coordinated efforts to address AMR across different sectors.

AMR is a critical One Health issue, with the spread of multidrug-resistant pathogens among animals, humans, and the environment complicating infection treatment due to biofilms. This underscores the need for vigilant monitoring and control measures to manage the spread of antibiotic resistance.

Chemical biocides are widely used to control infections in healthcare, industry, and targeted home hygiene, interacting with bacterial cells primarily by targeting the cytoplasmic membrane and enzymes. However, improper usage or sublethal concentrations of biocides can lead to antimicrobial resistance and promote the transfer of resistance genes63. This concern is heightened by the potentially harmful effects of chronic biocide exposure on human health and the selection of less susceptible bacterial isolates64.

Quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs), such as benzalkonium chloride, are commonly used in disinfectants for medical and food-processing environments, as well as in cosmetics and pharmaceuticals65. In our in vitro study, disinfectants containing peracetic acid, isopropanol, and QACs were the most effective against bacterial species, with QAC-based disinfectants showing particular efficacy in Bangladesh. However, prolonged use of QACs in Egypt has led to resistance in poultry settings66.

Sodium hypochlorite has been shown to reduce biofilm activity in bacteria like Enterococcus faecalis and Klebsiella pneumoniae, improving effectiveness at higher concentrations67,68. Recent studies suggest that combining oxidizing agents like sodium hypochlorite and hydrogen peroxide with novel agents, such as chlorhexidine-conjugated gold nanoparticles, can be particularly effective in eliminating K. pneumoniae and preventing biofilm formation69,70. While our study found that disinfectant A had minimal effectiveness, sodium hypochlorite-based disinfectants have been reported to be highly effective against certain bacterial species, such as S. lentus and M. luteus42. Implementing a sustainable control strategy and raising breeders’ knowledge and awareness is essential for the efficient management and mitigation of K. pneumoniae infection.

Conclusion

Klebsiella pneumoniae is notably present in poultry, resident birds, water, equine populations, and humans, with biofilm formation and ESBL genes contributing to its persistence. This investigation revealed that sodium hypochlorite product inhibits and clears K. pneumoniae with varying antibiotic resistance. The effect increased as the concentration increased within the range of bactericidal concentration. Comprehensive surveillance, biosecurity protocols, and efficient infection control methods are essential to minimize its spread and lower the risk of infection in animal and human populations. Collaborative efforts among veterinarians, wildlife biologists, public health officials, and environmental scientists are essential to understanding and addressing the complex dynamics of K. pneumoniae transmission across these interconnected ecosystems.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this published article.

References

Wareth, G., Sprague, L. D., Neubauer, H. & Pletz, M. W. Klebsiella pneumoniae in Germany: An overview on spatiotemporal distribution and resistance development in humans. Ger. J. Microbiol. 1, 16–25. https://doi.org/10.51585/gjm.2021.0004 (2021).

Kahin, M. A. et al. Occurrence, antibiotic resistance profiles and associated risk factors of Klebsiella pneumoniae in poultry farms in selected districts of Somalia Reginal State, Ethiopia. BMC Microbiol. 24(1), 137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-024-03298-1 (2024).

Estell, K. E. et al. Pneumonia caused by Klebsiella spp in 46 horses. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 30(1), 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.13653 (2016).

Da Silva, A. A. et al. Causes of equine abortion, stillbirth, and perinatal mortality in Brazil. Arq. Inst. Biol. 87, e0092020. https://doi.org/10.1590/1808-1657000092020 (2020).

Arafa, A. A. et al. Determination of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from horses with respiratory manifestation. Vet. World. 15(4), 827–833. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2022.827-833 (2022).

Marzouk, E. et al. Proteome analysis, genetic characterization, and antibiotic resistance patterns of Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates. AMB Express 14(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-024-01710-7 (2024).

Priyanka, A., Akshatha, K., Deekshit, V. K., Prarthana, J. & Akhila, D. S. Klebsiella pneumoniae Infections and Antimicrobial Drug Resistance. Model Organisms for Microbial Pathogenesis, Biofilm Formation and Antimicrobial Drug Discovery (Springer, 2020).

Mourão, J. et al. Decoding Klebsiella pneumoniae in poultry chain: Unveiling genetic landscape, antibiotic resistance, and biocide tolerance in non-clinical reservoirs. Front Microbiol. 15, 1365011. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1365011 (2024).

Smith, O. M., Snyder, W. E. & Owen, J. P. Are we overestimating risk of enteric pathogen spillover from wild birds to humans?. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 95(3), 652–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12581 (2020).

Atta, H. I., Idris, S. M., Gulumbe, B. H. & Awoniyi, O. J. Detection of extended spectrum beta-lactamase genes in strains of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from recreational water and tertiary hospital waste water in Zaria, Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Health. Res. 32(9), 2074–2082. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2021.1940884 (2022).

Samreen, A. I., Malak, H. A. & Abulreesh, H. H. Environmental antimicrobial resistance and its drivers: A potential threat to public health. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 27, 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2021.08.001 (2021).

Ibrahim, A. N., Khalefa, H. S. & Mubarak, S. T. Residual contamination and biofilm formation by opportunistic pathogens Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in poultry houses isolated from drinking water systems, fans, and floors. Egypt. J. Vet. Sci. 54(6), 1041–1057. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejvs.2023.211147.1502 (2023).

Wingender, J. & Flemming, H. C. Biofilms in drinking water and their role as reservoir for pathogens. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 214(6), 417–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2011.05.009 (2011).

Suresh, K. & Pillai, D. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance, biofilm formation, efflux pump activity, and virulence capabilities in multi-drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from freshwater fish farms. J. Water Health 22(4), 721–734. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2024.382 (2024).

Shree, P., Singh, C. K., Sodhi, K. K., Surya, J. N. & Singh, D. K. Biofilms: Understanding the structure and contribution towards bacterial resistance in antibiotics. Med. Microecol. 16, 100084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmic.2023.100084 (2023).

Guerra, M. E. S. et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilms and their role in disease pathogenesis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 12, 877995. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.877995 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Investigation of LuxS-mediated quorum sensing in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Med. Microbiol. 69(3), 402–413. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.001148 (2020).

Zheng, J. X. et al. Biofilm formation in Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia strains was found to be associated with CC23 and the presence of wcaG. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 8, 21. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2018.00021 (2018).

Ashwath, P. et al. Biofilm formation and associated gene expression in multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from clinical specimens. Curr. Microbiol. 79(3), 73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-022-02766-z (2022).

Regué, M. et al. A gene, uge, is essential for Klebsiella pneumoniae virulence. Infect. Immun. 72(1), 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.72.1.54-61.2004 (2004).

Muner, J. J. et al. The transcriptional regulator Fur modulates the expression of uge, a gene essential for the core lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Klebsiella pneumoniae. BMC Microbiol. 24, 279. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-024-03418-x (2024).

Arafa, A. A. & Kandil, M. M. Antimicrobial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles against ESBL producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from equines in Egypt. Pak. Vet. J. 44, 176–82. https://doi.org/10.29261/pakvetj/2023.121 (2023).

Keikha, M. & Karbalaei, M. Biofilm formation status in ESBL-producing bacteria recovered from clinical specimens of patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 23(2), e200922208987. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871526522666220920141631 (2023).

Hu, Y. L., Bi, S. L., Zhang, Z. Y. & Kong, N. Q. Correlation between antibiotics-resistance, virulence genes and genotypes among Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical strains isolated in Guangzhou, China. Curr. Microbiol. 81(9), 289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-024-03818-2 (2024).

Hala, S. et al. The emergence of highly resistant and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae CC14 clone in a tertiary hospital over 8 years. Genome Med. 16(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-024-01332-5 (2024).

Aroca Molina, K. J., Gutiérrez, S. J., Benítez-Campo, N. & Correa, A. Genomic differences associated with resistance and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from clinical and environmental sites. Microorganisms 12(6), 1116. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12061116 (2024).

Gnanadhas, D. P., Marathe, S. A. & Chakravortty, D. Biocides–resistance, cross-resistance mechanisms and assessment. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 22(2), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1517/13543784.2013.748035 (2013).

European Commission. Biocides - Introduction. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/chemicals/biocides/index_en.htm (Accessed June 2016).

Hernández-Navarrete, M. J., Celorrio-Pascual, J. M., Lapresta Moros, C. & Solano Bernad, V. M. Fundamentos de antisepsia, desinfección y esterilización [Principles of antisepsis, disinfection and sterilization]. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 32(10), 681–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eimc.2014.04.003 (2014).

Sheldon, A. T. Antiseptic “resistance”: Real or perceived threat?. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40(11), 1650–1656. https://doi.org/10.1086/430063 (2005).

Çakmur, H., Akoğlu, L., Kahraman, E. & Atasever, M. Evaluation of farmers’ knowledge-attitude-practice about zoonotic diseases in Kars, Turkey. KAFKAS TIP BİL DERG. 5(3), 87–93 (2015).

Stringfellow K D. Evaluation of Agricultural Disinfectants and Necrotic Enteritis Preventatives in Broiler Chickens (Doctoral dissertation, Texas A & M University, 2010).

Rozman, U., Pušnik, M., Kmetec, S., Duh, D. & Šostar, T. S. Reduced susceptibility and increased resistance of bacteria against disinfectants: A systematic review. Microorganisms 9(12), 2550. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9122550 (2021).

Collee, J. G., Marmion, B. P., Fraser, A. G. & Simmons, A. Mackie and McCartney Practical Medical Microbiology 14th edn. (Churchill Livingstone, 1996).

Hansen, D. S., Aucken, H. M., Abiola, T. & Podschun, R. Recommended test panel for differentiation of Klebsiella species on the basis of a trilateral interlaboratory evaluation of 18 biochemical tests. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42(8), 3665–3669. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.42.8.3665-3669.2004 (2004).

Mario, E., Hamza, D. & Abdel-Moein, K. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae among diarrheic farm animals: A serious public health concern. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 102, 102077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2023.102077 (2023).

Salloum, T., Arabaghian, H., Alousi, S., Abboud, E. & Tokajian, S. Genome sequencing and comparative analysis of an NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST15 isolated from a refugee patient. Pathog. Glob. Health. 111, 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2017.1314069 (2017).

Samir, A., Abdel-Moein, K. A. & Zaher, H. M. The public health burden of virulent extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from diseased horses. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 22(4), 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2022.0004 (2022).

Mohammed, R., Nader, S. M., Hamza, D. A. & Sabry, M. A. Public health concern of antimicrobial resistance and virulence determinants in E. coli isolates from oysters in Egypt. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 26977. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77519-y (2024).

CLSI Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. CLSI Doc.M100 30th edn. (CLSI, 2020).

Magiorakos, A. P. et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18(3), 268–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x (2012).

Saha, O. et al. Evaluation of commercial disinfectants against Staphylococcus lentus and Micrococcus spp. of poultry origin. Vet. Med. Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8811540 (2020).

Montagna, M. T. et al. Study on the in vitro activity of five disinfectants against nosocomial bacteria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16(11), 1895 (2019).

Kolde, R. Pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps. R package version 1.0. 12. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pheatmap (2019).

Spencer, R. C. Predominant pathogens found in the European prevalence of infection in intensive care study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 15(4), 281–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01695658 (1996).

Cadavid, E., Robledo, S. M., Quiñones, W. & Echeverri, F. Induction of biofilm formation in Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13884 by several drugs: The possible role of quorum sensing modulation. Antibiotics (Basel) 7(4), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7040103 (2018).

De Rosa, F. G., Corcione, S., Cavallo, R., Di Perri, G. & Bassetti, M. Critical issues for Klebsiella pneumoniae KPC-carbapenemase producing K. pneumoniae infections: A critical agenda. Future Microbiol. 10(2), 283–94. https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb.14.121 (2015).

Seifi, K. et al. Evaluation of biofilm formation among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates and molecular characterization by ERIC-PCR. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 9(1), e30682. https://doi.org/10.5812/jjm.30682 (2016).

Karigoudar, R. M., Karigoudar, M. H., Wavare, S. M. & Mangalgi, S. S. Detection of biofilm among uropathogenic Escherichia coli and its correlation with antibiotic resistance pattern. J. Lab Physicians 1, 17–22. https://doi.org/10.4103/JLP.JLP_98_18 (2019).

Laban, S. E. et al. Dry biofilm formation, mono-and dual-attachment, on plastic and galvanized surfaces by Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus isolated from poultry house. Int. J. Vet. Science. https://doi.org/10.47278/journal.ijvs/2024.197 (2024).

Saha, U., Jadhav, S. V., Pathak, K. N. & Saroj, S. D. Screening of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates reveals the spread of strong biofilm formers and class 1 integrons. J. Appl. Microbiol. 135(11), lxae275 (2024).

Hamam, S. S., El Kholy, R. M. & Zaki, M. E. S. Study of various virulence genes, biofilm formation and extended-spectrum β-lactamase resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from urinary tract infections. Open Microbiol. J. 13, 249–255 (2019).

Elmeslemany, R. & Yonis, A. E. Pathogenicity of bacterial isolates associated with high mortality in duckling in Behira province. Egypt. J. Anim. Health. 3, 41–53 (2023).

Davies, Y. M. et al. Virulence and antimicrobial resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from passerine and psittacine birds. Avian Pathol. 45(2), 194–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079457.2016.1142066 (2016).

Daehre, K. et al. ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in the broiler production chain and the first description of ST3128. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2302. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02302 (2018).

Ferreira, R. L. et al. High prevalence of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae harboring several virulence and β-lactamase encoding genes in a Brazilian intensive care unit. Front. Microbiol. 9, 3198. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.03198 (2019).

Barati, A. et al. Isolation and characterization of aquatic-borne Klebsiella pneumoniae from tropical estuaries in Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13(4), 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13040426 (2016).

Muhsin, E. A., Nimr, H. K. & Al-Jubori, S. S. Estimation of the role of Mrk Genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from river waters and clinical isolates. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 26(6), 1319–1328 (2022).

Poulou, A. et al. Outbreak caused by an ertapenem-resistant, CTX-M-15-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 101 clone carrying an OmpK36 porin variant. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51(10), 3176–3182. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01244-13 (2013).

Siqueira, A. K. et al. Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Phylogroup KpI in dogs and horses at veterinary teaching hospital. Vet. Med. Public Health J. 1(2), 41–47 (2020).

Belas, A., Menezes, J., Gama, L. T. & Pomba, C. Sharing of clinically important antimicrobial resistance genes by companion animals and their human household members. Microb. Drug Resist. 10, 1174–1185. https://doi.org/10.1089/mdr.2019.0380 (2020).

Elshafiee, E. A., Kadry, M., Nader, S. M. & Ahmed, Z. S. Extended-spectrum-beta-lactamases and carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from fresh produce farms in different governorates of Egypt. Vet. World 15(5), 1191–1196. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2022.1191-1196 (2022).

Maillard, J. Y. & Pascoe, M. Disinfectants and antiseptics: Mechanisms of action and resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00958-3 (2024).

Sonbol, F. I., El-Banna, T. E., Abd El-Aziz, A. A. & El-Ekhnawy, E. Impact of triclosan adaptation on membrane properties, efflux and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli clinical isolates. J. Appl. Microbiol. 126(3), 730–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.14158 (2019).

Gerba, C. P. Quaternary ammonium biocides: Efficacy in application. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81(2), 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02633-14 (2015).

Abd El-Razek, N., Hassan, H. & Abd, El-Tawab A. Effect of various disinfectants on E, coli isolated from water pipes in broiler farms at Giza and Dakahlia Governorates, Egypt. J. Adv. Vet. Res. 13(9), 1761–1766 (2023).

Yanling, C., Hongyan, L., Xi, W., Wim, C. & Dongmei, D. Efficacy of relacin combined with sodium hypochlorite against Enterococcus faecalis biofilms. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 26, e20160608. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-7757-2016-0608 (2018).

Huang, C., Tao, S., Yuan, J. & Li, X. Effect of sodium hypochlorite on biofilm of Klebsiella pneumoniae with different drug resistance. Am. J. Infect. Control 50(8), 922–928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2021.12.003 (2022).

Ahmed, A., Khan, A. K., Anwar, A., Ali, S. A. & Shah, M. R. Biofilm inhibitory effect of chlorhexidine conjugated gold nanoparticles against Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microb. Pathog. 98, 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2016.06.016 (2016).

Olmedo, G. M., Grillo-Puertas, M., Cerioni, L., Rapisarda, V. A. & Volentini, S. I. Removal of pathogenic bacterial biofilms by combinations of oxidizing compounds. Can. J. Microbiol. 61(5), 351–356. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjm-2014-0747 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The cooperation of the poultry and equine farm owners is highly appreciated.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.A., H.S.K., Z.A., and K.A.A. participated in the study design, bacterial isolation and identification, and molecular detection of biofilm genes by PCR. H.S.K. performed the experiments; D. H. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was conducted according to the guidelines of the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt, and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and use committee, Vet Cu ((VET. CU. IACUC; approval no. Vet CU 18042024926). All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt. The study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. The oral consent of the humans involved in the study was obtained from all owners after they had been informed of the use of nasal swab samples. Ethical clearance to use human subjects was obtained from the designated health facility (National Research Centre, Giza, Egypt).

Consent for publication

All authors have read the manuscript and consent to publish.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khalefa, H.S., Arafa, A.A., Hamza, D. et al. Emerging biofilm formation and disinfectant susceptibility of ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci Rep 15, 1599 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84149-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84149-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

MXene-coated paper microextraction patch for in vitro metabolic profiling to identify Klebsiella pneumoniae

Microchimica Acta (2026)

-

Thyme-synthesized silver nanoparticles mitigate immunosuppression, oxidative damage, and histopathological alterations induced by multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecalis in Oreochromis niloticus: in vitro and in vivo assays

Fish Physiology and Biochemistry (2025)

-

The antibacterial activity, action mechanisms and prospects of Baicalein as an antibacterial adjuvant

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology (2025)