Abstract

This study investigates the application of various neural network-based models for predicting temperature distribution in freeze drying process of biopharmaceuticals. For heat-sensitive biopharmaceutical products, freeze drying is preferred to prevent degradation of pharmaceutical compounds. The modeling framework is based on CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) and machine learning (ML). The ML models explored include the Single-Layer Perceptron (SLP), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN), and Deep Neural Network (DNN). Model optimization is achieved through the Fireworks Algorithm (FWA). Results reveal promising performance across all models, with the MLP demonstrating the highest accuracy on both test and training datasets, achieving an R2 score of 0.99713 and 0.99717 respectively. The SLP also exhibits strong performance, with an R2 of 0.88903 on the test dataset. The FCNN and DNN models also perform admirably, achieving R2 scores of 0.99158 and 0.99639 on the test dataset respectively. These results highlight the efficiency of neural network-driven models, specifically the MLP, in precisely forecasting temperature values based on spatial coordinates. Additionally, the integration of the Fireworks Algorithm for model refinement yields advantages in improving the predictive performance of these models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In biopharmaceutical manufacturing, large macromolecules are produced in a series of cell cultivation and purification processes. Biopharmaceutical products have gained more attention as the major therapeutics for various disease treatment. Some examples of biopharmaceutical products include vaccines, hormones, proteins, etc. Continuous operation and process understanding are of major challenges in developing biopharmaceutical production1,2. Since these materials are sensitive to heat, normal drying by heating is not applicable for biopharmaceuticals. The method of freeze drying is preferred which does not apply heat for removal of moisture and drying the products3. The main phenomenon in the freeze drying is based on the phase diagram of the system and removal of liquid phase via freezing the feed4.

Design and optimization of freeze-drying process is challenging as both mass and heat transfer phenomena must be taken into account for analysis of the process. Indeed, temperature (T) and concentration (C) change over time during this process, and they must be controlled in order to meet the required specifications. The process of freeze drying can be well understood and optimized via the development of predictive computational models. The models based on mass and heat transfer can be developed to track the changes in moisture and concentration over time. Indeed, unsteady state models are needed to be developed for this process to understand it. The main mechanistic model which can be developed and used for freeze drying simulation is computational fluid dynamics (CFD) which relies on numerical solution of mass and heat transfer equations to obtain concentration and temperature distribution in the process5,6. CFD has been recognized as powerful tools for simulation of heat transfer cases with great accuracy7,8,9. However, implementing CFD for processes is tedious and computationally expensive which demands for other computational methods which are easier to be implemented.

Recent development of artificial intelligence (AI)-based models has opened new horizons for application and integration of AI methods to mechanistic modeling to build advanced hybrid computational techniques for different processes. In this approach, AI models such as machine learning can be combined with CFD models to predict process with less computational cots10.

The field of machine learning (ML) has gained considerable attention in recent decades due to its broad range of applications in various domains. Machine learning (ML) utilizes statistical and computational methodologies to facilitate the integration of data by machines. A primary obstacle in machine learning is constructing precise and dependable models that can effectively apply to novel data11,12. The investigated models encompass the Single Layer Perceptron (SLP), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN), and Deep Neural Network (DNN). The process of model optimization is accomplished by employing the Fireworks Algorithm (FWA).

These four neural network architectures were chosen to address diverse regression tasks, while also enabling experimentation with their variants to explore their adaptability and performance. The Single Layer Perceptron (SLP) serves as a baseline model due to its simplicity and suitability for linear regression, making it a foundational tool for initial analysis. Building on this, the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) introduces additional layers, allowing it to capture non-linear relationships, which are essential in complex datasets. Fully Connected Neural Networks (FCNNs) enhance this capability with dense connectivity between all layers, effectively leveraging structured input data. Finally, Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) provide the depth and versatility to handle highly complex regression challenges across varied domains. By trying different configurations and depths of these architectures, we aim to strike a balance between model complexity, learning capacity, and task-specific performance. This systematic approach ensures a thorough exploration of neural network capabilities tailored to the given regression problems.

This paper makes a great contribution to the field of biopharmaceuticals through the exploration and evaluation of various neural network-based models. The models are implemented for a freeze-drying process which is used for drying biopharmaceuticals. Temperature distribution is obtained by using CFD and machine learning models for the first time to track the changes of parameters in the process in unsteady state conditions. By investigating the performance of SLP, MLP, FCNN, and DNN models, coupled with optimization using the Fireworks Algorithm (FWA), valuable insights are provided into the effectiveness of these models for predicting temperature based on generated CFD dataset. This is indeed a hybrid strategy to build simple models for complex processes such as freeze drying. The findings demonstrate the superior performance of the MLP model in accurately forecasting temperature, followed by strong performances from FCNN and DNN models. These insights not only advance the understanding of predictive modeling techniques in spatial temperature forecasting but also offer practical implications for stakeholders in meteorology, environmental science, and urban planning by providing robust tools for temperature prediction. The models along with optimization and CFD are developed for the first time for simulation of freeze-drying process.

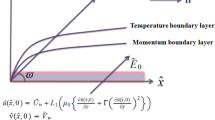

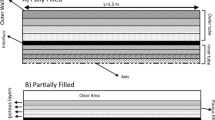

Dataset and process

In this study, the process of freeze drying is simulated with CFD and machine learning models. The goal is to obtain the temperature distribution inside the dryer at different locations. Indeed, the temperature distribution in a 3D domain was determined. For the CFD simulation, COMSOL Multiphysics 3.5 software was used which operates based on finite element scheme13. Molecular diffusion and conduction were considered for mass transfer and heat transfer, respectively14. Therefore, the dataset comprises spatial coordinates (X, Y, Z) paired with respective temperature readings (T) in Kelvin (K). With over 55,000 data entries, this dataset offers an extensive understanding of the correlation between spatial locations and temperature records. The spatial coordinates (X, Y, Z) function as the predictor variables, whereas the temperature (T) serves as the response variable to be forecasted.

In Fig. 1, a pair plot is presented, illustrating the relationships between different variables in the dataset. Each scatter plot depicts the correlation between pairs of variables, while histograms along the diagonal represent the distribution of individual variables. Figure 2 showcases boxplots for each variable in the dataset. This is indeed the first step for visualization of the dataset and see how the variables are changing within the domain of process.

Computations and modeling

Pre-processing step

As mentioned before, the datasets for machine learning are obtained by numerical simulation of heat and mass transfer on a simple 3D domain, and the data was extracted for machine learning models. Before diving into the core analysis, it’s crucial to prepare the data adequately through pre-processing steps. This ensures that the data is clean, standardized, and appropriately split for robust analysis.

-

1.

Outlier Detection using Cook’s Distance Method: Outliers can significantly impact the analysis and interpretation of data. Cook’s distance method is a robust technique used to detect influential outliers in a dataset. By measuring the impact of each data point on the regression coefficients, Cook’s distance helps identify observations with substantial leverage on the model. These outliers can then be examined further to determine if they should be retained or removed from the dataset15.

-

2.

Normalization using Z-Score Normalization Method: The process of normalization is crucial in order to maintain a consistent scale for variables, thereby preventing any individual feature from exerting excessive influence on the analysis as a result of its larger magnitude. A frequently employed technique for normalization is Z-score normalization, wherein each feature is subjected to a transformation involving the subtraction of the mean and division by the standard deviation. The aforementioned procedure involves circularizing the data around zero, accompanied by a standard deviation of one, in order to establish a consistent scale for all variables16.

-

3.

Data Set Splitting into Test and Train Sets: Splitting the dataset into training and testing subsets is necessary to accurately evaluate a predictive model. A random split allocates 20–80% of the data to the test set and the rest to the training set.

Single layer perceptron (SLP)

This technique serves as a flexible model applicable to a range of purposes such as classification, regression, and emulating wave propagation17. The initial incarnation of neural networks, the single layer perceptron model, marked a pivotal moment in their evolution. Comprising two layers—the input and output layers as indicated in Fig. 3- interconnected by multiple artificial neurons (ANs), it served as the foundation for more complex architectures.

In operation, the single layer perceptron processes input data \(\:\left({x}_{1},{x}_{2},\dots\:,{x}_{m}\right)\) at the input layer. These inputs are weighted and aggregated, culminating in a summation denoted by18:

For the K-th neuron in the output layer, this aggregation determines the total information received. The output of the K-th neuron is governed by the activation function f, applied to the difference between the aggregated sum and a threshold \(\:{{\uptheta\:}}_{k}\), as follows18,19:

Conceptually, the single-layer perceptron constructs hyperplanes to segregate distinct datasets within a high-dimensional space. Its effectiveness lies in tackling linearly separable problems adeptly. However, it struggles with datasets that lack linear distinction. To broaden the applicability of neural networks and address more complex real-world challenges, the multilayer perceptron emerged as a natural evolution from its predecessor.

Multi-layer perceptron (MLP)

Expanding upon the foundation laid by SLP, the MLP represents a significant advancement in neural network architecture. Unlike its predecessor, the MLP comprises multiple layers of neurons, introducing hidden layers between the input and output layers20,21. The multi-layered architecture increases the capacity of the model to detect complex trends and correlations in the data.

In operation, the MLP functions similarly to the SLP. Input data \(\:\left({x}_{1},{x}_{2},\dots\:,{x}_{m}\right)\) is processed at the input layer and propagated through the network. Each neuron in the hidden layers aggregates weighted inputs and applies an activation function, contributing to the subsequent layers’ computations. The output layer then produces the final predictions or classifications. The structure of MLP is shown in Fig. 4.

Mathematically, the output of the K-th neuron in the MLP can be expressed as:

Where \(\:{n}_{h}\) represents the number of neurons in the hidden layer, and \(\:{w}_{ij}^{\left(1\right)}\), \(\:{w}_{jk}^{\left(2\right)}\), \(\:{{\uptheta\:}}_{j}^{\left(1\right)}\), and \(\:{{\uptheta\:}}_{k}^{\left(2\right)}\) denote the weights and thresholds associated with the connections between layers. Here, i indexes the input neurons, j indexes the neurons in the hidden layer, and k indexes the output neurons, ensuring clarity in the roles of each layer within the network.

Compared to the SLP, the MLP offers several key advantages. Firstly, its ability to incorporate multiple hidden layers enables the model to learn complex, non-linear correlations within the data. This makes it more adept at handling tasks with intricate patterns or features. Additionally, the MLP’s capacity for hierarchical feature learning enhances its performance on tasks where the input-output relationships are not linearly separable.

Fully connected neural network (FCNN)

The Fully Connected Neural Network is a comprehensive architecture in which every neuron in a particular layer is linked to all neurons in the following layer, enabling sophisticated data representations and intricate pattern identification22.

In operation, the FCNN mirrors the principles of its predecessors. Input data \(\:\left({x}_{1},{x}_{2},\dots\:,{x}_{m}\right)\) is initially fed into the input layer. From there, each neuron in the subsequent layers aggregates the weighted inputs from all neurons in the preceding layer and applies an activation function. This process continues through the network until the output layer produces the final predictions. Mathematically, the output of the K-th neuron in an FCNN can be expressed as:

where \(\:{n}_{l-1}\) and \(\:{n}_{l-2}\) denotes the quantity of neurons in the previous and pre-previous layers, respectively, and \(\:{w}_{ij}^{\left(l-1\right)},{w}_{jk}^{\left(l\right)}\), \(\:{{\uptheta\:}}_{j}^{\left(l-1\right)}\), and \(\:{{\uptheta\:}}_{k}^{\left(l\right)}\) denote the weights and thresholds associated with the connections between layers.

The FCNN’s comprehensive connectivity enables it to capture intricate relationships within the data, making it highly adaptable to a wide range of tasks. By leveraging its dense interconnections, the FCNN excels at learning complex patterns and extracting high-level features from input data.

The Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN) serves as a general architecture where every neuron in one layer is connected to every neuron in the subsequent layer, enabling comprehensive information flow and feature extraction. The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) is a specific type of FCNN distinguished by its inclusion of multiple hidden layers and its capability to model complex, non-linear relationships. While all MLPs are inherently FCNNs, the reverse does not hold true, as FCNNs encompass a broader range of architectures that may not include the hierarchical, multi-layered structure characteristic of MLPs.

Deep neural network (DNN)

Enter the Deep Neural Network (DNN), an advanced architectural evolution that pushes the boundaries of neural network capabilities to unprecedented levels. Unlike its predecessors, the DNN comprises numerous layers of neurons, allowing for exceptionally deep architectures capable of learning intricate features and representations from data23.

In operation, the DNN functions similarly to other neural networks, albeit with an increased depth. Input data \(\:\left({x}_{1},{x}_{2},\dots\:,{x}_{m}\right)\) is initially processed at the input layer and propagated through multiple hidden layers. Each layer aggregates weighted inputs from the previous layer, applies an activation function, and passes the transformed information to the subsequent layer. This sequential processing persists until the ultimate layer generates the intended outcome.

Mathematically, the output of the K-th neuron in a deep neural network can be expressed as:

Here, \(\:{n}_{l-1}\) and \(\:{n}_{l-2}\) stand for the quantity of neurons in the previous and pre-previous layers, respectively, and \(\:{w}_{ij}^{\left(l-1\right)}\), \(\:{w}_{jk}^{\left(l\right)}\), \(\:{{\uptheta\:}}_{j}^{\left(l-1\right)}\), and \(\:{{\uptheta\:}}_{k}^{\left(l\right)}\) denote the weights and thresholds associated with the connections between layers.

The key distinguishing feature of the DNN lies in its depth, which enables it to learn hierarchical representations of data. By iteratively transforming the input through multiple layers, the DNN can extract increasingly abstract features, capturing complex patterns and relationships that may not be discernible to shallower architectures24.

In essence, the Deep Neural Network (DNN) represents the pinnacle of neural network sophistication, harnessing its deep architecture to unlock unprecedented learning capabilities. Through its depth-driven hierarchical processing, the DNN stands as a cornerstone of modern artificial intelligence, powering applications across various domains with unparalleled efficiency and accuracy.

Fireworks Algorithm (FWA)

The Fireworks Algorithm (FWA)25 stands as an optimization technique inspired by the bursts of fireworks to generate sparks, leading to a unique search strategy that reduces search complexity in comparison with alternative algorithms. Three basic operations—exploration, variation, and selection—make up the method. The generated sparks during the explosion phase are used for entity scouting in the surrounding area, so enabling efficient exploration and exploitation of the search space26. In the phase of diversity enhancement, a firework is ignited, resulting in the generation of multiple sparks. Some of these sparks have the potential to generate a distinct spark that is intended to promote population diversity. The selection process necessitates consideration of fireworks, ignited sparks, and other spark categories. The most adept individuals are promptly selected as the initial seed for the subsequent iteration cycle, followed by a repetition of the process. The remaining group members are selected randomly. Unique sparks are generated and spread around existing sparks, while regular sparks are uniformly dispersed around the firework based on the intensity of the ongoing spark27,28.

In this method, sparkles exhibit two unique characteristics: the quantity of explosions (\(\:{s}_{i}\)) and amplitude (\(\:{A}_{i}\)). The luminosity of a spark is inversely related to its magnitude, whereas the brightness of sparks resulting from an explosion is clearly correlated with the quantity of sparks it produces. This amount can be calculated using the following formula29:

In the fireworks algorithm, the formula for determining the count of sparks produced by an explosion takes into account a number of parameters. It incorporates \(\:{S}_{max}\) as the maximum size of sparks set and evaluates the current adaptability value of the fireworks population, \(\:f\left({X}_{i}\right)\), within the range defined by \(\:{f}_{min}\) and \(\:{f}_{max}\). Furthermore, parameters like a and b represent the lower and upper limits of the spark generation ratios, respectively. The \(\:\xi\:\) variable is a tiny real number added to avoid encountering division by zero, and the \(\:round\left(\right)\) function is applied for standard rounding of the outcome. The amplitude is calculated using the following formula26:

The amplitude of the i-th firework is represented by \(\:{A}_{i}\), with \(\:{A}_{max}\)indicating the maximum amplitude. Here is how to calculate the locations of the sparks from each fireworks26:

where r stands for a random number between − 1 and 1.

In each iteration, m unique fireworks are randomly selected from a population of size N. Then, a spark is generated for each firework via a mutation operation. The mutation operator is understood by the following28,30:

The expression randGauss(1, 1) denotes the generation of a random value drawn from a Gaussian distribution with a variance and mean both set to 1.

The optimization process utilizing the FWA is centered around the fitness function defined as the mean R2 score obtained from a 5-fold cross-validation. This metric ensures a robust evaluation of model performance, minimizing overfitting and capturing generalization across different data partitions. To achieve effective optimization, the FWA parameters were set as follows:

-

Population size (NN): 75.

-

Maximum number of sparks (MM): 80.

-

Amplitude (AA): 0.6.

-

Convergence criterion (ε): 0.000001.

-

Number of iterations: 500.

Results and discussion

The performance of four neural network-based models, namely SLP, MLP, FCNN, and DNN, was evaluated for spatial temperature forecasting using a dataset containing over 55,000 data points. The inputs consisted of spatial coordinates (X, Y, Z), while the output was the corresponding temperature (T) in Kelvin.

Table 1 outlines the performance metrics for each model on the training dataset, encompassing the coefficient of determination (R² score), root mean squared error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE). Table 2 similarly displays the performance metrics for the test dataset.

Overall, the MLP model demonstrated the highest predictive accuracy on both the test and training datasets, achieving R2 scores of 0.99713 and 0.99717, respectively. This indicates that the MLP model was able to explain over 99% of the variance in temperature based on spatial coordinates. Additionally, the MLP model exhibited the lowest RMSE and MAE values among all models, indicating minimal errors in temperature prediction.

The SLP model exhibited satisfactory performance, with R2 scores of 0.88903 on the test dataset and 0.88491 on the training dataset. While its performance was lower compared to the MLP model, the SLP model still achieved acceptable accuracy in temperature forecasting.

The FCNN and DNN models exhibited robust performance, as evidenced by their respective R2 scores of 0.99158 and 0.99639 on the test dataset. These results indicate that both models were able to capture complex relationships between spatial coordinates and temperature, resulting in accurate temperature predictions.

The optimized MLP model emerged as the top-performing neural network for spatial temperature forecasting, achieving exceptional predictive accuracy across multiple evaluation metrics. Specifically, the MLP achieved mean R² scores of 0.99717 on the training dataset and 0.99713 on the test dataset, demonstrating its ability to explain over 99% of the variance in temperature predictions based on spatial coordinates. This performance was further substantiated through 5-fold cross-validation, which confirmed the MLP’s robustness and minimal variance in predictions (see Table 3).

Among all the models, the MLP also exhibited the lowest RMSE (0.8177 on the test dataset) and MAE (0.4382), underscoring its precision in temperature forecasting. While the FCNN and DNN models delivered strong performances (R² scores of 0.99158 and 0.99639, respectively), they were slightly outperformed by the MLP in both accuracy and error minimization. The SLP model, serving as a baseline, lagged behind with an R² score of 0.88903 on the test dataset.

These results highlight the MLP model’s efficacy in capturing complex spatial temperature patterns, making it an ideal choice for applications in meteorology, environmental science, and urban planning. The remaining analyses are done using MLP model which its error distributions shown in Fig. 5.

The correlation between three input parameters (x, y, z) and a response variable (T) is depicted in Fig. 6. In this graph, the input parameters are represented by the x, y, and z axes, while the hue of each data point indicates the corresponding value of the output variable T(K). The similar trend was reported in previous work on simulation of similar process13. The partial effect of coordinates on T(K) is depicted in Figs. 7, 8 and 9. The results indicated that temperature is changing along the dryer length in the process which is governed by conduction heat transfer. The developed ML models are able to simulate the changes in the process. The temperature in the process at a desired location and time can be controlled by manipulation of the process parameters. Once the model has been trained and validated it can be used for controlling the moisture content as the it is dependent on the temperature value. The slice of simulated temperature distribution via CFD is illustrated in Fig. 10 which is in agreement with the T distribution obtained by ML model (see Fig. 5).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of neural network-based models, including the SLP, MLP, FCNN, and DNN, in predicting temperature based on spatial coordinates for simulation of freeze-drying process for biopharmaceuticals. CFD computations were performed, and the data used for learning ML algorithms. Through the utilization of FWA for model optimization, significant improvements in predictive accuracy were achieved across all models. Among these, the MLP emerged as the top-performing model, showcasing exceptional accuracy on both test and training datasets. These findings underscore the potential of neural network models in spatial temperature forecasting applications and highlight the importance of leveraging optimization techniques for enhancing predictive capabilities. Moving forward, further research can explore additional optimization strategies and model architectures to further improve predictive accuracy and robustness in temperature forecasting tasks.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (Majed A. Bajaber) on reasonable request.

References

Partopour, B. & Pollard, D. Advancing Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing: Economic and Sustainability Assessment of end-to-end Continuous Production of Monoclonal Antibodies (Trends in Biotechnology, 2024).

Sharma, A. et al. On the role of excipients in biopharmaceuticals manufacture: modelling-guided formulation identifies the protective effect of arginine hydrochloride excipient on spray-dried olipudase alfa recombinant protein. Int. J. Pharm. 662, 124466 (2024).

Hsein, H. et al. Tableting properties of freeze-dried trehalose: physico-chemical and mechanical investigation. Int. J. Pharm. 648, 123598 (2023).

Ge, S. et al. Research progress on improving the freeze-drying resistance of probiotics: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 147, 104425 (2024).

Piechnik, E. et al. Experimentally validated CFD-tool for a freezing simulation in a small-scale freeze-dryer. J. Food Eng. 367, 111888 (2024).

Srisuma, P., Barbastathis, G. & Braatz, R. D. Mechanistic modeling and analysis of thermal radiation in conventional, microwave-assisted, and hybrid freeze drying for biopharmaceutical manufacturing. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 221, 125023 (2024).

Dillon, P. A dual-solver CFD model for conjugate heat transfer in continuous thermal processing. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 49, 103337 (2023).

Hekal, M. et al. Hydro-thermal performance of fabric air duct (FAD): experimental and CFD simulation assessments. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 47, 103107 (2023).

Xu, T. et al. Extended CFD models for numerical simulation of tunnel fire under natural ventilation: comparative analysis and experimental verification. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 31, 101815 (2022).

Dong, X. et al. Deep learning with multilayer perceptron for optimizing the heat transfer of mixed convection equipped with MWCNT-water nanofluid. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 57, 104309 (2024).

Alpaydin, E. Introduction to Machine Learning (MIT Press, 2020).

Shinde, P. P. & Shah, S. A review of machine learning and deep learning applications. In Fourth international conference on computing communication control and automation (ICCUBEA). (IEEE, 2018).

Alqarni, M., Alqarni, A. A. Computational and intelligence modeling analysis of pharmaceutical freeze drying for prediction of temperature in the process. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 61, 105136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2024.105136 (2024)

COMSOL MultiPhysics V. 3.5a: Heat Transfer Module Model Library. (2008).

Dı́az-Garcı́a, J. A. & González-Farı́as, G. A note on the Cook’s distance. J. Stat. Plann. Inference. 120(1–2), 119–136 (2004).

Henderi, H., Wahyuningsih, T. & Rahwanto, E. Comparison of Min-Max normalization and Z-Score normalization in the K-nearest neighbor (kNN) algorithm to test the accuracy of types of breast Cancer. Int. J. Inf. Inform. Syst. 4(1), 13–20 (2021).

Raudys, Š. On the universality of the single-layer perceptron model. In Neural Networks and Soft Computing: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Neural Networks and Soft Computing, Zakopane, Poland, June 11–15, 2003. Springer. (2002).

Du, K. L. et al. Perceptron: Learning, generalization, model selection, fault tolerance, and role in the deep learning era. Mathematics 10(24), 4730 (2022).

Qin, Y. et al. MLP-based regression prediction model for compound bioactivity. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 946329 (2022).

Bisong, E. & Bisong, E. The multilayer perceptron (MLP). Building Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models on Google Cloud Platform: A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners, pp. 401–405. (2019).

Taud, H. & Mas, J. Multilayer perceptron (MLP). Geomatic Approaches for Modeling Land Change Scenarios, pp. 451–455. (2018).

Jia, B. & Zhang, Y. Spectrum Analysis for Fully Connected Neural Networks (IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 2022).

Cichy, R. M. & Kaiser, D. Deep neural networks as scientific models. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23(4), 305–317 (2019).

Chen, C. H. et al. A study of optimization in deep neural networks for regression. Electronics 12(14), 3071 (2023).

Tan, Y. & Zhu, Y. Fireworks algorithm for optimization. in Advances in Swarm Intelligence: First International Conference, ICSI 2010, Beijing, China, June 12–15, 2010, Proceedings, Part I 1. (Springer, 2010).

Li, J. & Tan, Y. A comprehensive review of the fireworks algorithm. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR). 52(6), 1–28 (2019).

Zheng, S., Janecek, A. & Tan, Y. Enhanced fireworks algorithm. In 2013 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation. (IEEE, 2013).

Jin, H. et al. Intelligence-based simulation of solubility of hydrogen in bitumen at elevated pressure and temperature: models optimization using fireworks algorithm. J. Mol. Liq. 390, 122948 (2023).

Schryen, G. Parallel computational optimization in operations research: a new integrative framework, literature review and research directions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 287(1), 1–18 (2020).

Yang, L. et al. Improving the drilling parameter optimization method based on the fireworks algorithm. ACS Omega. 7(42), 38074–38083 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman university researchers supporting project number (PNURSP2024R340), princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman university, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors express their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid university, Saudi Arabia, for funding the work through research group program under grant number RGP2/589/45.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T. A. H: writing, drafting, editing, analysis, validation, supervisionJ. A. A: writing, drafting, editing, analysis, resources, investigationM. A. B: writing, drafting, editing, formal analysis, conceptualizationH. I. A: writing, drafting, editing, data analysis, investigationH. J. A: writing, drafting, editing, analysis, resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Hagbani, T., Alamoudi, J.A., Bajaber, M.A. et al. Theoretical investigations on analysis and optimization of freeze drying of pharmaceutical powder using machine learning modeling of temperature distribution. Sci Rep 15, 948 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84155-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84155-z