Abstract

This study investigates the nonlinear dynamics of a system with frequency-dependent stiffness using a MEMS-based capacitive inertial sensor as a case study. The sensor is positioned directly on a rotating component of a machine and consists of a microbeam clamped at both ends by fixed supports with a fixed central proof mass. The nonlinear behavior is determined by electrostatic forces, axial and bending motion coupling, and frequency-dependent stiffness. The numerical Galerkin approach is employed for discretization of the coupled differential equations in spatial coordinates. To obtain the sensor response as a function of frequency, a continuation arc-length method based on weak formulation energy balance method is used. This approach uses a physical gradient descent learning based method to obtain unknown coefficients of the considered response. The presented method computes the periodic steady-state solution of the design by considering different frequency contents within the response, including different harmonics of the response expansion. However, the primary and secondary resonances at various harmonic frequencies within the response can be predicted. In this article, the dynamic behavior of the design is investigated by testing different levels of shaft acceleration and different bias voltages. The purpose of the evaluation is to determine the frequency-dependent stiffness of the accelerometer for different levels of shaft speed, taking into account various sensor geometric parameters. The analysis demonstrates the behavior of the sensors under different conditions, particularly highlighting the nonlinearity of the sensor, which causes primary and secondary resonances in the first, second, and third harmonic responses of the accelerometer, especially at higher bias voltages. Fast Fourier analyses indicated that the transversal vibration amplitude of the structure in the second and third harmonies are so considerable that cannot be neglected. The mathematical method used in this study can be applied by researchers and engineers in the design of such sensors to effectively create these devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Analysing a system’s dynamic features is critical, especially when it exhibits nonlinearity and fluctuating coefficients. Understanding and correctly interpreting these metrics is vital for appropriate system evaluation. Inertial sensors, such as MEMS capacitive devices, monitor a structure’s acceleration and angular velocity, while accelerometers measure dynamic and static acceleration forces. Vibration sensors are used to detect and prevent equipment damage caused by vibrations in a variety of sectors, including rotating electronics, drones, rotating machinery, and vehicles. Piezoelectric (PE) accelerometers, capacitive accelerometers, and piezoresistance (PR) accelerometers are widely used technologies for vibration measurements. MEMS devices, particularly MEMS sensors1,2,3, are used in a variety of industrial applications due to their numerous advantages4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. For example, MEMS-based accelerometers, have higher resolution sensitivity than comparable accelerometers. As a result, these devices have been used in a variety of commercial applications, including navigation, instrumentation, rotary machinery, vehicle airbags, and so on.

Piezoelectric accelerometers employ the influence of particular materials to dynamically rather than statically determine changes in mechanical variables such as shock or vibration. The operation of such sensors is similar to that of other transducers in that one kind of energy is converted to another and produces an electric signal dependent on the specific property or condition of the object. Piezoelectric accelerometers can have high or low impedance. The former has a charge output that is turned into a voltage based on the capacity of the impedance converter, whereas the latter operates on the power supply device and a small charge-to-voltage converter to deliver relevant output signals to receiving devices12. Piezoelectric sensors feature basic architectures that allow them to be easily combined with other components. Compared to capacitive and piezoresistive accelerometers, they have higher sensitivity and better signal-to-noise ratios. As a result, these fast response and extremely sensitive sensors are the most commonly utilized vibration sensors in industrial applications.

Several research papers on the efficiency, manufacture, and application of piezoelectric sensors have been presented13,14. Zhang et al.15 developed multi-parameter modeling for the acceleration sensor’s sensitivity features to examine the design of the six-degree-of-freedom accelerometer. It was numerically simulated using the ANSYS software, and the presented (6-DOF) accelerometer prototype was built. The experimental data showed that the model’s sensitivity characteristics followed the same pattern as the empirical test results of the sensor. Lee et al.16 investigated the design characteristics and efficiency of a piezoelectric acceleration sensor based on Pb (Zr,Ti)O3. The computational analysis and experimental examination revealed that the acceleration sensor’s sensitivity is a design-dependent characteristic.

The accelerometer can achieve optimal results by meeting the requirement for resonance frequency and sensitivity. Chen et al.17 proposed a high-temperature piezoelectric accelerometer. The proposed BiFeO3–BaTiO3 structure could be used in high-temperature piezoelectric sensor applications. The suggested sensor may operate at a greater maximum temperature than PZT-5A-based piezoelectric sensing instruments. It was discovered that the piezoelectric sensor (BFBT25-Mn) has stable sensitivity at 400 °C. As a result, for high-temperature measurement applications, BFBT25-Mn ceramic could be a formidable opponent. Another research paper18 disclosed the layout and structure of a piezoelectric vibration sensor consisting of four L-shaped microbeams with a thin film of PZT of 1 μm. The data collected showed that the proposed high-sensitivity piezoelectric accelerometer has a low resonant frequency.

Hu et al.19 proposed a MEMS-based piezoelectric acceleration sensor based on ScAlN/AlN. Employing FEM, They investigated how piezoelectric parameters and cantilever stiffness affect the structure’s resonant frequency. Yang et al.20 proposed a miniaturized MEMS device for acceleration sensing form by six trapezoidal microbeams with polygonal topology. They investigated the impact of beam stiffness on the structure’s natural frequency as well as its output voltage.

Piezoresistive accelerometers are inertial sensors that can determine their acceleration by attaching to a reference frame. These sensors with reduced noise outputs provide more local stresses. In these sensors, the resistance of the material increases as the applied pressure increases. These sensors are less snsitive than piezoelectric accelerometers and are better suited to car crash testing. Several types of studies on novel manufacturing processes and design techniques for piezoresistive accelerometers are given. The dynamic behavior and static performance of a polymer 3-axis piezoresistive micro accelerometer with an innovative improved design was investigated by Khlifi et al.21. Comparing the calculated induced stress fields in this investigation with those of two comparable silicon-based devices, a significant reformation was observed. A MEMS piezoresistive accelerometer was simulated and experimentally validated by Jecy et al. in another paper22.

The sensor was restricted with Pyrex glasses on top and bottom to allow it to withstand the acceleration shock. Vibration detection could occur significantly earlier in the structure electroplated with gold at the gap distance of 27 m. MEME accelerometers are typically used in extremely high-temperature situations; however, modern MEMS Si-based microelectromechanical system accelerometers cannot sustain temperatures above 500 °C. To address this problem, a MEMS acceleration sensor was designed and constructed. The structure was able to accurately evaluate signals with different g-values of acceleration because it was fabricated using bulk SiC processing technology23. The sensitivity of the design was found to be 0.21 mV/g with a linearity of 99.8% at an input voltage of 5 V.

Acceleration causes a change in electrical capacitance, which is the principle behind capacitive accelerometers work. These sensors have small size, good temperature performance, high sensitivity, and low manufacturing cost. Various researchers have studied the MEMS capacitive sensors for industrial applications. A capacitive accelerometer fabricated based on MEMS technology for use in automotive applications was designed and analyzed in a study24. The study aimed to improve the bandwidth operation of an accelerometer by preserving its sensitivity. To ensure the safety of the new structure, the sensor’s natural frequency and mode shapes were calculated. The work presented by Li et al.25 included the design, numerical modeling, optimization, and fabrication of a MEMS-based single-axis capacitive accelerometer utilizing a comb drive. The finger-gap-to-finger-gap spacing ratio was optimized in gap-variable capacitive accelerometers, resulting in high sensitivity. Electrical sensitivity remained nearly constant at frequencies ranging from 100 to 200 Hz.

To monitor the vibration of the shaft in rotary machines, MEMS-based accelerometers, specifically capacitive accelerometers, are placed on shaft or on-bearing as they are crucial for vibration measurements. Microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) accelerometers allow for direct embedding of the accelerometer into rotary machine components, enabling the determination of both lateral and torsional vibrations. The use of a single instrument to gather vibration data substantially increases efficiency in monitoring rotary machines. Pedotti et al.26 demonstrated a wireless sensor network utilizing MEMS accelerometers, with one sensor node installed on the support table and the other on the shaft. The Fast Fourier Transform was utilized to examine the steady-state solution of the machine’s vibration through acceleration signals. The results demonstrate that the presented structure can be utilized in engineering applications as instrumentation with low-cost for monitoring the rotating machines strength.

Aswin et al.27 presented a MEMS-based 3-axis accelerometer for monitoring vibration in rotating machines. The system included a data analysis and vibration data acquisition system that used wireless communication principles. To verify real-time measurement accuracy, the stability of data transmission was tested over a specified duration. Koene introduced a wireless universal measurement unit (UMU) positioned on the spinning component of the machine28. The structure featured a unique combination of traits, including effortless installation and a broad measurement range. The signal processing method presented with UMU allowed for the precise determination of lateral and torsional vibration frequencies. Another study introduced a MEMS wireless accelerometer implanted inside a hollow rotor, which could improve vibration detection29. The device was capable of accurately measuring acceleration in a rotating coordinate system. The research emphasized the functionality developed through the use of internal accelerometers. Ouakad and Sedighi investigated nonlinear structural behavior of a micro-actuator design with non-parallel plates30. In that structure, by tuning its geometrical design, softening behavior of the structure as well as hardening like behaviors could be obtained easily. In another research work pull in phenomenon in electrostatically micro switch was analyzed utilizing Artificial Neural Network31. Comparing the obtained results with the experimental data indicated that the presented method could predict the threshold voltage with acceptable accuracy. Farokhi et al. conducted a comprehensive experimental and theoretical study on the nonlinear dynamic response of a base-excited, initially curved panel clamped at both ends32. Their results demonstrated a strong correlation between theoretical predictions and experimental observations, confirming the accuracy of the theoretical model in capturing the panel’s complex dynamic behavior. In another research work, experimental vibration analysis was utilized to extract the dynamic characteristics of a rotor structure33. Through this approach, model parameters were identified based on the experimental results, offering detailed insights into the rotor’s dynamic behavior.

The quantification and comprehension of sensor measurement uncertainty, particularly in shaft accelerometers, is crucial to ensuring the precision and reliability of obtained data. Uncertainty refers to the potential for error or doubt present in the measurements, and several factors contribute to this in sensor technology. For accurate measurements, proper alignment and mounting of accelerometers on the rotating shaft are essential. Misalignment or improper attachment may lead to inaccurate readings and impact the quality of collected data. The calibration procedure defines the correlation between the measured physical quantity (e.g., acceleration) and the output of the sensor. Calibration mistakes, including systematic errors and offsets, may cause uncertainty in measurements34. The accelerometer’s sensitivity (output change per unit of input change) may experience nonlinearity across its measurement spectrum, leading to deviations from the ideal output35,36.

Calibrating the sensor across its full range is necessary to account for variations. Random noise in the sensor’s output affects the precision of measurements and introduced uncertainty. The resolution of the sensor also is crucial in detecting the smallest change in the measured quantity37. The uncertainty of the sensor can be influenced by other factors including drift and temperature effects, sampling rate, environmental conditions, and signal processing38. Various methods, such as uncertainty analysis and error propagation, are used to quantify uncertainty. Calibration certificates frequently provide data on a sensor’s uncertainty, which is often expressed as a percentage of full-scale reading or in absolute units. Understanding uncertainty aids in the evaluation of the reliability of sensor measurements. It also helps determine whether the measurement meet the accuracy criteria for the intended application.

Studying the frequency response of sensors, including shaft accelerometers, is crucial for determining their performance characteristics and suitability for specific applications39,40. These sensors play a vital role in measuring dynamic phenomena, such as vibrations, oscillations, or rapidly changing forces. Determining a sensor’s frequency response is critical to ensuring accurate and reliable measurement of these dynamic events across different frequencies. The frequency response curve of a sensor denotes its bandwidth, which reflects the range of frequencies for accurate measurements41,42. Understanding the bandwidth is essential to select the appropriate sensor for a given application. Certain frequencies may cause sensors to exhibit resonances, where their sensitivity significantly increases or decreases. By understanding the frequency response, one can identify and avoid resonant frequencies that might compromise accurate or damage the sensor. In cases involving periodic or repetitive events, precise harmonic analysis and comprehension of harmonics present in measured signals depend on the system’s response in frequency domain. Understanding the frequency response ensures compatibility with the system dynamics. This knowledge eliminates stability issues when integrating sensors into complicated control loops or systems. Studying the frequency response of sensors is crucial in comprehending their dynamic behavior, choosing the appropriate sensor for a specific application, guaranteeing measurement accuracy, and designing resilient and effective systems. This characterization and validation are fundamental, ensuring reliable and meaningful data acquisition across various industries.

In certain mechanical systems, such as those involved in muscular contraction dynamics43, the system’s rigidity undergoes temporal changes similar to those observed in Hill’s system44. These periodic changes are referred to as Mathieu systems45. However, in the current scenario, these adjustments are frequency-dependent. Within the realm of beams, the lateral rigidity of a beam depends on the longitudinal force it bears. In configurations when an inertia sensor with a beam set up is located within a rotating shaft or radially oriented mechanism, the centrifugal forces related to the shaft’s rotational velocity fluctuate with changes in the assumed rotational velocity. Additionally, the operational frequency depends on this rotational speed. Consequently, in such complex configurations, the system’s rigidity fluctuates with changes in the excitation frequency.

The present study presents a comprehensive model for the dynamics of a microelectromechanical (MEMS) accelerometer when mounted on a rotating shaft, with the objective of serving as a shaft-mounted accelerometer. By examining the behavior of the accelerometer in this distinctive configuration, in which the equivalent stiffness is dependent on rotational velocity, we are able to provide new insights into how the device responds to a range of frequencies. This analysis is of great importance for understanding the operational limits and measurement applicability and accuracy of MEMS accelerometers in rotational applications. In the absence of eccentricity, the positioning of two accelerometers on the shaft is sufficient for the accurate measurement of acceleration. However, in the event of eccentricity, which may arise in practical applications due to misalignment or manufacturing imperfections, the use of additional sensors, such as proximity sensors, may be necessary to account for the lateral displacement of the shaft. The incorporation of eccentricity effects could serve to enhance the model’s robustness, and this represents a potential avenue for future research. Furthermore, this study employs a continuation-based method in conjunction with the arc-length method to obtain a comprehensive frequency response of the system. This approach enables the capture of the response not only at the fundamental harmonic but also at higher harmonics, which become relevant depending on the system’s nonlinearity and the excitation frequency. The FFT analysis demonstrates the existence of significant amplitude components in the initial harmonics, which are pivotal in expanding the solution response through energy or harmonic balance methods. This methodology facilitates more precise predictions of the accelerometer’s performance, offering valuable insights into its response to rotational velocity-dependent stiffness, particularly under varying bias voltages and acceleration amplitudes. The accelerometer under study has a beam structure with fixed ends and a centrally located fixed microplate. The microbeam and substrate layer are subjected to the applied voltage of biasing. The system’s nonlinear differential equations governing the axial and transversal motions of the sensor, which is exposed to the exciting acceleration of the shaft are extracted. The non-dimensional equations are descritized with the use of the Galerkin method. The accelerometer’s frequency domain response is determined using the gradient-descent learning approach, which evaluates the sensor’s steady-state response while considering different response harmonics. Furthermore, the study investigates both the main resonance and secondary resonances in the sensor’s behavior across several harmonics is conducted.

Model description

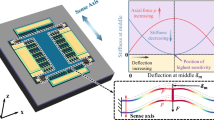

Figure 1a indicates the shaft and the bearing’s diagram with the accelerometers embedded in the shaft. The center of the shaft is denoted by \({O}_{2}\) with the eccentricity value of \(\overline{r }\) and angle of \(\theta\) from the bearing’s center (\({O}_{1}\)). The on-shaft accelerometers are MEMS-based capacitive sensors. The detailed schematic of each sensor is shown in Fig. 1b. The sensors are embedded directly on the rotary component of the machine circumferentially, enabling the determination of both radial and tangential components of the shaft’s acceleration in inertial Cartesian coordinates, respectively. Each accelerometer consists of a fixed microbeam at both ends with a microplate embedded in the middle of it. The whole structure is assumed to be made of polysilicon crystal. The structure is exposed to a biasing DC voltage to form a capacitor. The actuating acceleration produced by the rotation of the shaft leads the structure to vibrate longitudinally (in \(x\) direction) as well as transversally (in \(y\) direction). The electrostatic force is produced through the variation in the capacitor’s capacitance. The structure’s nonlinear differential equations exposed to the input shaft acceleration and the electrostatic force are extracted and solved simultaneously. In the case when there is no eccentricity and the shaft is vibrated about the center of the bearing, two sensors are needed to measure both components of the shaft acceleration in inertial Cartesian coordinates. As shown in Fig. 1a, one of the sensors is located in position A and the other one can be positioned at B with the angle \(\varphi\) from the sensor in position A. In this work, the static behavior as well as dynamic behavior of the design are investigated and discussed in detail. It’s assumed that external forces such as friction, air resistance, or thermal effects do not significantly impact the model’s accuracy. Moreover, the entire sensor structure is supposed to be made of polysilicon crystal, suggesting uniform mechanical and electrical properties. The rationale behind the utilization of two sensors and their specific positioning in Fig. 1 is to obtain a comprehensive representation of the vector components of acceleration at a specific point on the shaft. Given that acceleration is a vector quantity, it is comprised of multiple components, which are typically radial and tangential in this context or in the X or Y directions in a fixed coordinate system. The utilization of two accelerometers allows for the measurement of these components, thereby facilitating a comprehensive evaluation of the shaft’s dynamic response under operational conditions. This configuration is essential for acquiring a precise and comprehensive understanding of the shaft’s behavior. However, it should be noted that in the case of considering eccentricity of the shaft, these two accelerometers will be inadequate. The illustrations were added to the text.

Mathematical modeling

Absolute acceleration of the shaft center

As seen in Fig. 1, the center of the shaft is denoted by \({O}_{2}\) with the eccentricity value of \(r\) and angle of \(\theta\) from the bearing’s center (\({O}_{1}\)). It is considered that the shaft has an angular velocity \(({\omega }_{r})\). However, as the center point of the shaft can be vary over time relative to the bearing center point, the shaft’s absolute rotational velocity (\(\overline{\Omega }\)) is expressed as follows:

The absolute position of any point on the microbeam can be expressed as follows:

where \({u}_{i}\) and \({w}_{i}\) are the displacements of a point located at the length of the microbeam in the ith sensor in the \(x\), and \(y\) directions, respectively. \(R\) is the shaft radius, and \({\overline{P} }_{i}^{c}\) is the absolute position of any point in the microbeam in the ith circumferential sensor.

The absolute velocity and acceleration of a point in the ith circumferential acceleration sensor are expressed:

In relations (3, 4), \({\overline{v} }_{os}\) and \({\overline{a} }_{os}\) are the velocity and acceleration of the shaft center point and are expressed as:

where \({\overline{e} }_{r}\), \({\overline{e} }_{\theta }\) are the radial and circumferential unit vectors of the polar coordinate, \(\overline{I }\) and \(\overline{J }\) are the unit vectors of the inertial Cartesian coordinate. Therefore, the absolute velocity (\({\overline{V} }_{i}^{c}\)) and acceleration (\({\overline{A} }_{i}^{c}\)) of a point in ith circumferential acceleration sensor can be given in the following form:

\({\overline{V} }_{i}^{c}\) and \({\overline{A} }_{i}^{c}\) are the absolute velocity and acceleration of a point in ith circumferential acceleration sensor. Based on the unit vectors presented in Fig. 1a, the following relationship between unit vectors of coordinates can be written:

So, considering the gravity acceleration and applying the relation (9), the radial and tangential components of the absolute acceleration for the circumferential accelerometers can be presented as:

In relation (10), \(g\) is the gravitational acceleration. It is seen from relation (10) that to know the acceleration of the center of the shaft through the acceleration of a point in the sensor \(({\ddot{u}}_{i},{\ddot{w}}_{i})\), values of \(r, \dot{r,}\theta ,\dot{\theta ,}\) and \(\ddot{\theta }\) should be calculated.

It’s assumed that there is no eccentricity and the shaft vibrates about to the center of the bearing. Therefore, the tangential and radial component of the sensor for the accelerometers located in positions A and B can be presented as:

In relations (11,12)\({\left({\overline{A} }_{A}^{c}\right)}_{y}\) and \({\left({\overline{A} }_{A}^{c}\right)}_{x}\) are the absolute tangential and radial components of the acceleration for the accelerometer located in position A, and \({\left({\overline{A} }_{B}^{c}\right)}_{y}\) and \({\left({\overline{A} }_{B}^{c}\right)}_{x}\) are the radial and the tangential components of the acceleration for the accelerometer located in position B, respectively.

The vibration motion of the sensor

Considering that the beam is an extensible micro-beam, and including the nonlinear von Kármán term, the amount of the strain (\({\varepsilon }_{y})\) is given by the following:

where \(w\left(x,t\right)\) is the deflection of the beam. \(u\left(x,t\right)\) is the beam displacement in the \(x\)-direction. The von-Karman nonlinear strain term is shown by \(\frac{1}{2}{\left(\frac{\partial w}{\partial x}\right)}^{2}\)

Considering that the microbeam material follows Hooke’s law, the axial stress can be obtained as:

where \({E}_{b}\) refers to the beam’s Young’s modulus. So, the axial force is obtained by integrating the axial stress over the beam’s cross-section area of the beam as:

where \({A}_{b}\) is the beam’s cross-section area. The governing nonlinear equation of motion in longitudinal \((x)\) and transversal \((y)\) directions can be expressed as follows:

where \({\rho }_{b}\) is the density of the beam, \({M}_{p}\) indicates the mass of the microplate, and \(I\) indicates the beam’s moment of inertia, \({c}_{1}\) and \({c}_{2}\) are the structure’s damping coefficients of the in the \((x)\) and \((y)\) directions. Considering shaft with a constant rotation speed, applying relation (15), in the Eqs. (16) and (17), the system of equations governing the structure’s motion in \(y\)-direction and \(x\)-direction for the sensor in position A are expressed as:

In Eq. (18), the first term on the right-hand side represents the stiffness term, the second term corresponds to the inertial effect, the third term is the damping term, and the fourth term represents the coupling effect arising from mid-plane stretching of the beam. In Eq. (19), \({F}_{e}\) is the generated electrostatic force per unit length of the beam and can be presented as follows46,47,48:

where \({g}_{0}\) denotes the air space between two electrodes, \({\varepsilon }_{0}\) denotes the vacuum primitivity, \(V\) is the biasing voltage applied to the electrodes as indicated in Fig. 1, and \(k\) is the air dielectric coefficient.

The accompanying boundary conditions of Eqs. (18), and (19) are as follows:

By considering the following parameters:

Equations (18) and (19) can be rewritten in the non-dimension form:

with the following parameters:

Numerical solution

The proposed sensor’s material characteristics and geometrical parameters are listed in Table 1.

Static analysis

By setting the time-dependent terms (inertial and damping terms) to zero in the main equations (23) and (24), we derive the static equations. The static form of the Eqs. (23, 24) are as follows:

Utilizing the effective Galerkin, the approximate solution for \({\widehat{u}}_{s}(\widehat{x})\) and \({\widehat{w}}_{s}(\widehat{x})\) is considered as:

The error functions are expressed via the substitution of the solutions (29) into the Eqs. (26), and (27):

Applying the following energy balance integrals:

Equations (30) and (31), take the following form:

with the following coefficients:

The Shape functions applied in calculating the results are as47:

In static analyses of the structure, by considering the geometrical parameters listed in Table 1, the pull-in voltage is calculated and obtained 10.59 V. To validate the result, without considering the rotational frequency of the shaft, and considering the geometrical and material parameters of Ref49, the maximum deflection of the beam is calculated and the results are compared with the results in Ref49. The comparison is indicated in Fig. 2.

Comparison the design’s deflection with the results presented in Ref49 without considering the rotational frequency of the shaft.

Dynamic analysis

By applying the energy balance integrals (Eq. (31)) to the primary non-dimensional equations (Eqs. (23) and (24)), we derive the following dynamic equations:

with the coefficients in Appendix 1.

The equivalent stiffness of the structure, denoted as \({K}_{eq}\) in Eq. (37), comprises several components: a term representing the mechanical stiffness of the structure, four terms associated with midplane stretching with hardening effects, one term corresponding to the electrostatic force with a softening effect, and a final term representing the stiffness influenced by the shaft’s frequency.

Frequency response analysis

Frequency response analysis is an essential tool for understanding the capabilities, limitations, and areas for optimization of accelerometers. With this knowledge, engineers can more effectively design and implement sensors for a diversity of applications, such as industrial machinery monitoring, aerospace, automotive safety systems, and structural health monitoring. However, capacitive accelerometers, due to electrostatic force, are nonlinear in nature, where the relationship between input and output is not proportional. Nonlinear frequency response analysis helps characterize and understand the behavior of such systems under varying frequency inputs. The time-dependent unknown coefficients relating to the Eqs. (36) and (37) are defined in vector form as follows:

Considering the new time variable Eqs. (36) and (37) can be presented as follow:

The magnitude of the electrostatic force is dependent upon the displacement of the structure. Furthermore, the transverse vibration and the longitudinal motion of the design are coupled, resulting in nonlinear equations for the structure. It can therefore be predicted that in the periodic response of the structure to an input acceleration field with a single harmonic content, higher harmonics may also be observed. To provide further clarification, it can be stated that in a linear system, the response to a single harmonic input is a single harmonic response. Nevertheless, in the present case, the second, third, and higher harmonics in the sensor’s dynamic response are a consequence of the intrinsic nonlinearities inherent to capacitive structures. These nonlinearities result in the emergence of higher-order harmonics under single-frequency actuation, which can be attributed to the inclusion of quadratic and cubic terms in the governing equations. The presence of these harmonics can be readily discerned through the use of FFT analysis, particularly when their amplitudes are significant. While conventional time-scaling methods do not emphasise these harmonics, incorporating them into the energy balance represents a viable solution. The exclusion of these harmonics may result in an overestimation of the first harmonic amplitude, thereby reducing the accuracy of the model. It is therefore essential to account for these harmonics in order to accurately predict the system’s response and ensure a realistic representation of its dynamic behavior. So, for the periodic frequency response of Eq. (39), a Fourier expansion can be written as:

The solution of (40) is written based on a reduced-order model for (42) as follows:

where

In the solution based on the Fourier expansion, an initial guess is considered for the coefficients to find the unknown coefficients. The coefficients obtained from the solution of the linearized system can be considered as an initial presumption. The coefficients are revised to find a proper solution, by considering the design’s energy in a period as the cost function. The coefficients are adjusted by using the gradient-based method. However, the coefficients will satisfy the equations governing the motion of the structure in a weak form or an integral form with adequate precision. The function of energy for the solutions \(k\) step can be as follows:

where

And \({\overline{W} }_{e}\) is the weight functions vector as follow:

Consequently when the actuation frequency increases to a new value \(\omega +\Delta \omega\) the vector with unknown coefficient values will be as \({\overline{G} }^{(j)}+\Delta {\overline{G} }^{(j)}\) . The implicit arc length method is a numerical approach designed to solve nonlinear equations. It has also been successfully used in nonlinear frequency response analysis. This method is particularly useful when dealing with phenomena such as bifurcation, jumps, subharmonic isolas, and snapback behavior. This method accurately traces the frequency response curve without considering the incremental step frequency as a fixed value. Instead, it gradually increases from zero to a desired value with dynamic increments based on the behavior of the frequency response curve and the unknown amplitude values. Because the implicit Arc Length method considers the frequency increment as an unknown value, an additional equation must be defined. This equation, commonly referred to as the arc length equation, is defined as follows, and is a constraint equation that allows conventional methods such as the Newton–Raphson method converge in softening, hardening, or limit points.

where \(\sigma\) is a scaling factor. Since the implicit Arc Length method is iterative, assuming that the amplitude and frequency increments \(\Delta {\overline{Q} }^{(j)}\) and \(\Delta \omega\) satisfy the Arc Length Eq. (44), it is possible to obtain a simplified linearized version of this constraint equation, adopting the idea of Riks and Wempner for (i + 1)th iteration, i.e.50,51,52.

For convenience, we combine the energy function (Eq. (43)) with the arc length constraint (Eq. (47)) and call it the cost function. The magnitude of the cost function at (n + 1)th iteration can be written in terms of its value at the nth iteration using the Taylor expansion series as follows:

Supposing that the cost function’s desired value is zero, the unknown coefficient variations’ magnitude is evaluated as:

Consequently, the updated value for amplitude and frequency increments will be as follows:

The process continues until acceptable results are obtained that satisfy both the energy balance equation and the arc length equation to a specified level of accuracy.

Considering \(\omega\) \(=21.7\) , and actuating acceleration values \(({\ddot{X}}_{e}={\ddot{X}}_{e}=2g)\), Fast Fourier analyses, has been done for the structure in the case of \(V=5\) volts and plotted in Fig. 3. Moreover, time history and phase plane are also shown in the same plot. As shown in the FFT analysis of the structure (Fig. 3), the vibration amplitudes for the fourth harmonic and higher are significantly smaller than those of the first, second, and third harmonics, allowing them to be reasonably neglected. It’s also observed that the structure shows linear behavior for actuating force.

As can be seen from the FFT analysis of the structure (Fig. 3), the frequency content of the response indicates that when the system is actuated by a specific frequency, certain harmonics have considerable amplitudes and should be taken into account in the solution response. In particular, the first, second and third harmonics exhibit considerable vibration amplitudes, whereas the fourth harmonic and higher have significantly smaller amplitudes, thereby justifying their reasonable exclusion. Furthermore, depending on the biasing voltage and acceleration amplitude, in some instances the first harmonic may be sufficient, whereas in other instances higher harmonics must also be included to accurately capture the system’s behavior. Methods such as the Energy Balance or Harmonic Balance employ this frequency content to expand the response across different harmonics, with the importance of each harmonic influenced by the level of nonlinearity in the system.

Considering \(V=9.5\) volts, and actuating acceleration values \(({\ddot{X}}_{e}={\ddot{X}}_{e}=2g)\), Fast Fourier analyses, has been done for two different values of actuating frequency and plotted in Fig. 4. The presented results show that the vibrational amplitude of the structure in the second and third harmonies are important in analyzing the dynamic behavior of the sensor as their magnitude are considerable compared to the vibrational amplitude in the first harmony response of the sensor. It’s also indicated that in higher values of actuating frequency the nonlinear behavior of the structure decreases.

FFT analyses has been done for different values of acceleration amplitude and plotted in Fig. 5. It’s observed that higher actuating force increases the nonlinear behavior of the sensor.

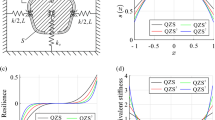

Supposing V = 5 Volts, the sensor’s transversal motion in the frequency domain in the first, second, and third harmonies for different values of the actuating acceleration values (\(g\)) is calculated for j = 1 (first mode) and indicated in Fig. 6a–c. \({A}_{1}^{(2)}\),\({A}_{2}^{(2)}\), and \({A}_{3}^{(2)}\) are the non-dimensional amplitude of transversal motion of the three harmonies of the response, and \(\omega\) is the non-dimension frequency of the shaft respectively.

Two separate resonances develop in the second harmonics of the accelerometer’s behavior for Vdc = 5 Volt. The main resonance occurs at \(\omega =21.7\), while the secondary resonance appears at \(\omega =10.8\) due to the nonlinearity of the equations. It also shown that the third harmonic has three different resonances. A major resonance is detected at \(\omega =21.7\), followed by secondary resonances at \(\omega =10.8\) and a third resonance at \(\omega =7.23\). When compared to the displacement amplitude in the first harmony response, the displacement amplitude in the structure’s second and third harmony responses is incredibly small.

Figure 7a–c show the design’s steady-state response in transversal displacement in three harmonics. The results are obtained for various actuating acceleration values (\(g\)), considering Vdc = 9.5 Volt. It’s observed that in the first harmonic of the response, for lower acceleration magnitudes, the structure shows softening nonlinearity behavior whereas for higher acceleration magnitudes, it shows the hardening nonlinearity behavior. It’s also seen that in higher applied biasing voltages, the decrement of the sensor’s equivalent stiffness is more obvious in comparison with the case when lower values of biasing voltage are applied to the structure. Three distinct resonances appear in the first, second, and third harmony responses; A primary resonance occurs at \(\omega =16.7\) and at \(\omega =7.35\) , and \(\omega =4.8\), the secondary resonances appear. In higher acceleration magnitudes of the shaft, the vibration amplitude of the structure increases which can lead to the increment of the accelerometer’s sensitivity. However, higher acceleration magnitudes grow up the nonlinearity behavior of the sensor, respectively.

In the mathematical model presented, two principal sources of nonlinearity are identified. The initial source of nonlinearity arises from the coupling between the transversal and longitudinal vibrations of the structure, particularly the midplane stretching term, which represents a form of geometric nonlinearity. The nonlinearity is influenced by the microbeam’s geometrical parameters, imparting a hardening effect on the structure’s response.

The second source of nonlinearity is attributable to the electrostatic force generated by the voltage applied to the electrodes. This electrostatic nonlinearity introduces a softening effect on the sensor’s response. Consequently, the sensor’s behavior is determined by the relative magnitudes of these nonlinearities under different geometrical configurations and operational conditions. As the external acceleration—and therefore the vibration amplitude—increases, the influence of the geometric nonlinearity begins to surpass that of the electrostatic nonlinearity. At higher vibration amplitudes, this shift causes the system’s response to transition from a softening to a hardening behavior.

When the structure is subjected to a biasing voltage in proximity to the pull-in voltage, the equivalent stiffness undergoes a notable decline, thereby conferring high sensitivity upon the sensor. However, this heightened sensitivity is accompanied by a trade-off, namely a narrowing of the measurable input range. Conversely, the application of a lower biasing voltage results in a reduction in the sensor’s sensitivity, accompanied by an expansion in the measurable input range. Therefore, the selection of the biasing voltage must be meticulously planned in accordance with the particular demands of the intended application, with due consideration given to whether the objective is to prioritize higher sensitivity or a more expansive measurement range53,54. This equilibrium permits the optimal performance of the sensor, which is adapted to the specific operational requirements.

It is crucial to recognise that operating in proximity to the pull-in voltage in capacitive accelerometers is inherently hazardous. This is due to the fact that the pull-in voltage is a consequence of a saddle-node bifurcation, which renders the sensor unstable and susceptible to being drawn towards the lower substrate. This indicates that exceeding the pull-in voltage results in the sensing element sticking to the substrate, which may lead to damage to the sensor. Such malfunctions can render the accelerometer inoperative and result in inaccurate measurements. Furthermore, operating the accelerometer consistently close to the pull-in voltage diminishes its capacity to function accurately within the intended measurement range, thereby compromising the reliability of the device, particularly in applications where precise measurements are critical. Therefore, it is essential to manage operating conditions meticulously to ensure optimal performance and safety in capacitive accelerometers.

It is also noteworthy that the model illustrates the system’s capacity for a multitude of intricate, non-linear behaviors, which can be attributed to the distinctive stiffness attributes imparted by the rotational configuration. Although we did not explicitly examine phenomena such as quasi-periodic responses, chaotic motion, internal resonance, isolas, or various bifurcation types (e.g. catastrophic bifurcations), the inherent nonlinearity of the MEMS structure suggests that such behaviors could emerge under certain conditions. The setup has the potential to exhibit a wide range of dynamic responses due to the presence of multiple sources of nonlinearity, including rotational stiffness dependence and frequency-sensitive behavior. While the current study provides an initial exploration, the modelling framework developed here is robust in terms of nonlinear dynamics, offering a promising foundation for future work.

The sensor’s steady state response in the acceleration magnitude of 0.1 g for a microplate with various widths is investigated and the obtained responses can be seen in Fig. 8.

It has been observed that increasing the width of the microplate enhances the produced electrostatic force. Consequently, this leads to a decrease in the equivalent stiffness of the sensor, resulting in a reduction of the vibrational amplitude of the structure. Figure 9 indicates the influence of the length of the microbeam on the dynamic behavior of the design. Increasing the microbeam length reduces the stiffness of the sensor and leads to the increment of the vibrational amplitude of the accelerometer in the sensors’ response in different harmonies. The enhancement of the vibration amplitude due to the increment of microbeam length is more considerable in the third harmonic response compared to the second harmonic. Moreover, increasing the microbeam length increases the design’s displacement amplitude more significantly in the first harmony than in the second harmonic response.

Figure 10 illustrates the relationship between the dimensionless equivalent stiffness of the accelerometer and the frequency ratio, analyzed for various widths of the proof mass (microplate). The results indicate that as the frequency ratio (corresponding to the shaft’s angular velocity) increases, the equivalent stiffness of the accelerometer decreases. Additionally, the analysis reveals that an increase in the microplate width further reduces the equivalent stiffness, with this effect becoming particularly pronounced at higher frequency ratios. This suggests that both the frequency ratio and the dimensions of the microplate play significant roles in influencing the dynamic response and sensitivity of the accelerometer.

Figure 11 indicates the equivalent rigidity of the structure for various magnitudes of the parameter describing the coupling between the shaft’s transversal and longitudinal motions. The results indicate that lower values of the coupling term lead to a decrease in the stiffness of the accelerometer.

Figure 12 demonstrates the influence of bias voltage and shaft frequency on the non-dimensional equivalent stiffness of the structure. The equivalent stiffness of the presented sensor is subject to influence by both the bias voltage and the shaft frequency. The combined effect of these two parameters is a reduction in sensor stiffness, which can be attributed to a softening effect on the structure.

Conclusion

The presented study investigates the nonlinear dynamics of a system with inherent nonlinearity, where rigidity varies with excitation frequency. The study focuses on a capacitive on-shaft MEMS-based accelerometer, which experiences nonlinearity due to electrostatic force and axial-flexural coupling. Furthermore, the rigidity of the system becomes frequency-dependent due to the variation of longitudinal force with rotation speed.

Two capacitive sensors were placed on the shaft to measure both radial and circumferential acceleration components. The sensor consisted of fixed microbeams at both ends with a central load in plate form. A bias DC voltage was applied to form a capacitor.

The structure’s nonlinear coupled differential equations of the motion in exposure to the actuating input exciting acceleration of the shaft were extracted. The frequency-dependent stiffness equations have been solved employing the numerical Galerkin approach in the spatial domain and the multidimensional energy balance method in the temporal domain, which allows to obtain the response in the frequency domain even if there is a multi-frequency actuation. Investigating the structure’s behavior in different frequency values by a learning method showed that for Vdc = 5 Volt, two distinct resonances occurred at \(\omega =21.7\) and \(\omega =10.8\) in the second harmonic of the accelerometer’s response. It was also indicated that three distinct resonances occur in the design’s response in the third harmony. At \(\omega =21.7\), a main resonance, at \(\omega =10.8\) , and \(\omega =7.23\) secondary resonances appeared in the sensor’s response in frequency domain. The amplitude of motion in the second and third harmonic responses of the structure was significantly lower than that of the first harmonic response. It was observed that at higher biasing voltages, the structure exhibited softening nonlinearity behavior for lower acceleration magnitudes in the first harmonic response, while it showed hardening nonlinearity behavior for higher acceleration magnitudes. The analysis of the effect of microbeam length revealed that the increase in vibration amplitude is more significant in the third harmonic in comparison with the second harmonic. Increasing the frequency ratio (angular velocity of the shaft) reduces the equivalent stiffness of the accelerometer. Additionally, selecting a wider microplate can decrease the equivalent stiffness of the accelerometer, particularly at higher shaft frequencies. In Fast Fourier analyses, the frequencies in different harmonies were detected in which the vibration amplitude in the first, second and third harmonies were considerable compared to the vibrational amplitude in higher harmonies. The obtained results can offer valuable insights for researchers and engineers involved in the design of shaft accelerometers, potentially improving sensor design and efficiency. Future research could explore additional parameters and investigate the use of soft dielectric materials to enhance capacitive sensors.

The angular velocity of the shaft was identified as a system parameter that reduces the equivalent stiffness of the device, thereby increasing the sensitivity of the sensor, based on the equations obtained. These findings suggest a potential avenue for optimizing accelerometer design, particularly for applications requiring increased responsiveness at higher operating frequencies.

The study presents definitive evidence of the non-linear behaviors observed in shaft-mounted MEMS accelerometers, including resonance shifts, amplitude-dependent responses, bifurcations and jumps. These arise from nonlinearities and stiffness variations linked to electrostatic force, as well as shaft angular velocity. It is of great importance to gain an understanding of and to accurately model these nonlinearities in order to guarantee effective vibration analysis and sensor stability. While this research does not explore quasi-periodic responses, chaotic motion, or internal resonance, it paves the way for future investigations into these dynamics. The findings indicate that accurately modelled, optimally placed MEMS accelerometers have the potential to enhance performance in rotational applications, such as industrial machinery and automotive systems. This provides a foundation for advancing MEMS sensors in demanding rotational environments.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tavakkoli, H., Abbaspour-Sani, E., Khalilzadeghan, A., Rezazadeh, G. & Khoei, A. Analytical study of mutual inductance of hexagonal and octagonal spiral planer coils. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 247, 53–64 (2016).

Rezazadeh, G., Ghanbari, M., Mirzaee, I. & Keyvani, A. On the mathematical modeling of a piezoelectrically actuated microsensor for simultaneous measurement of fluids viscosity and density. Measurement 43(10), 1516–1524 (2010).

Abazari, A. M., Khalilzadeghan, A., Abbaspour Sani, E., Rezazadeh, G. & Tavakkoli, H. Mutual inductance calculation between two coaxial planar spiral coils with an arbitrary number of sides. Microelectron. J. 85, 98–108 (2019).

Daeichin, M., Ozdogan, M., Towfighian, S. & Miles, R. Dynamic response of a tunable MEMS accelerometer based on repulsive force. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 289, 34–43 (2019).

Lee, S. H. & Lee, S. Fabrication of comb-structured acceleration sensors by roll-to-roll gravure printing. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Green Technol. 9, 409–420 (2022).

Ghanbari, M., Rezazadeh, G., Tolkani, V. M. & Sheikhlou, M. Dynamic analysis of a novel wide-tunable microbeam resonator with a sliding free-of-charge electrode. Nonlinear Dyn. 111, 8039–8060 (2023).

Ang, W. T., Khosla, P. K. & Riviere, C. N. Nonlinear regression model for low-g MEMS accelerometer. IEEE Sens. J. 7(1), 81–88 (2007).

Malayappan, B., Lakshmi, U. P., Rao, B. V. V. S. N. P., Ramaswamy, K. & Pattnaik, P. K. Sensing techniques and interrogation methods in optical MEMS accelerometers: a review. IEEE Sens. J. 22(7), 6232–6246 (2022).

Ghanbari, M., Rezazadeh, G. & Tolkani, V. M. Nonlinear dynamics of a tunable novel accelerometer, tunable with a microtriple electrode variable capacitor. Acta Mech. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00707-023-03552-z (2023).

Ghanbari, M. & Rezazadeh, G. A liquid state high sensitive accelerometer based on a micro-scale liquid marble. Microsyst. Technol. 26, 617–623 (2020).

Rezazadeh, G., Ghanbari, M., Mirzaee, I. Simultaneous measurement of fluids viscosity and density using a microbeam. In 5th International Conference on Perspective Technologies and Methods in MEMS Design 36–44 (2009).

Jiang, X., Kim, K., Zhang, S., Johnson, J. & Salazar, G. High-temperature piezoelectric sensing. Sensors 14(1), 144–169 (2014).

Koszewnik, A. et al. Nonlinear recurrence analysis of piezo sensor placement for unmanned aerial vehicle motor failure diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 14, 8289 (2024).

Song, K. et al. Pneumatic actuator and flexible piezoelectric sensor for soft virtual reality glove system. Sci. Rep. 9, 8988 (2019).

Zhang, D., Liu, J., Qin, L., Liu, J. & Li, M. Multiparameter modeling of piezoelectric six-degree-of- freedom accelerometer about sensitivity characteristics. IEEE Sens. J. 20(13), 7129–7137 (2020).

Lee, M. K., Han, S. H., Park, J. J. & Lee, G. J. A theoretical and empirical investigation of design characteristics in a Pb(Zr, Ti)O3-based piezoelectric accelerometer. Sensors 20(12), 3545 (2020).

Chen, J., Wu, J., Lu, Y., Wang, Y. & Cheng, J. High temperature piezoelectric accelerometer fabricated by 0.75BiFeO3–0.25BaTi ceramics with operating temperature over 4500C. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 232902 (2022).

Shi, S. et al. High sensitivity MEMS accelerometer using PZT-based four L-shaped beam structure. IEEE Sens. J. 22(8), 7627–7636 (2022).

Hu, B., Liu, Y., Lin, B., Wu, G. & Liu, W. A novel trapezoidal ScAIN/AIN-based MEMS piezoelectric accelerometer. IEEE Sens. J. 21(19), 21277–21284 (2021).

Yang, C. et al. A miniaturized piezoelectric MEMS accelerometer with polygon topological cantilever structure. Micromachines 13(10), 1608 (2022).

Khlifi, A. et al. Theoretical and numerical investigation of a new 3-axis SU-8 MEMS piezoresistive accelerometer. Microelectron. J. 128, 105552 (2022).

Jecy, G., Sekar, M. & Sankar, A. R. Damping analysis of a quad beam MEMS piezo resistive accelerometer. Int. J. Model. Simulat. 41(4), 256–264 (2020).

Zhai, Y. et al. Design, fabrication and test of a bulk SiC MEMS accelerometer. Microelectron. Eng. 260, 111793 (2022).

Ramakrishnan, J., Gaurav, R., Chandar, N. S. & Sudharsan, N. M. Structural design, analysis and DOE of MEMS-based capacitive accelerometer for automotive airbag application. Microsyst. Technol. 27, 763–777 (2021).

Li, Ru. et al. Design, modelling and characterization of comb-drive MEMS gap-changeable differential capacitive accelerometer. Measurement 169, 108377 (2021).

Santos Pedotti, L. A., Zago, R. M., Giesbrecht, M. & Fruett, F. Low-cost MEMS accelerometer network for rotating machine vibration diagnostics. IEEE Instrument. Meas. Mag. 23(7), 25–33 (2020).

Aswin, F., Dwisaputra, I. & Afriansyah, R. A. Online vibration monitoring system for rotating machinery based on 3-axis MEMS accelerometer. J. Phys. Series 1540(1), 012109 (2020).

Koene, I. et al. On-shaft wireless vibration measurement Unit and signal processing method for torsional lateral vibration. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 27(6), 5857–5868 (2022).

Jimenez, S., Cole, M. O. T. & Keogh, P. S. Vibration sensing in smart machine rotors using internal MEMS accelerometers. J. Sound Vib. 377, 58–75 (2016).

Ouakad, H. M. & Sedighi, H. M. Static response and free vibration of MEMS arches assuming out-of-plane actuation pattern. Int. J. Non-linear Mechan. 110, 44–57 (2019).

Aliasghary, M., Mobki, H. & Ouakad, H. M. Pull-in phenomenon in the electrostatically micro-switch suspended between two conductive plates using the artificial neural network. J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 8(4), 1222–1235 (2022).

Farokhi, H. et al. A nonlinear joint model for large-amplitude vibrations of initially curved panels: Reduced-order modelling and experimental validation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 211, 111239 (2024).

Jalal, H., Rafieian, F. & Haddad, K. H. Dynamic modeling and experimental verification on the rotor-armature structure of a steam turbine-generator unit. Appl. Math. Model. 107, 802–814 (2022).

Gaitan, M. & Geist, J. Calibration of triaxial accelerometers by constant rotation rate in the gravitational field. Measurement 189, 110528 (2022).

Li, Y., Tan, Q., Wen, J., Song, L. & Yang, F. Study of nonlinear vibration of resonant gyroscope based on uncertainty analyses method. Microelectron. J. 263, 111845 (2022).

Wei, Y., Yang, J., Li, P., Zhang, X. & Liang, P. Analysis and optimization method of the vibration rectification error of a pendulous accelerometer. IEEE Sens. J. 21(18), 19847–19856 (2022).

Gaitan, M., Bautista, I. M. L. & Geist, J. Reduction of calibration uncertainity due to mounting of three-axis accelerometers using the intrinsic properties model. Metrologia 58, 035006 (2021).

Garg, N. & Singh, M. Measurement uncertainty in primary calibration of accelerometer complex sensitivity at low frequencies. MAPAN 36, 821–831 (2021).

Fan, W., Wen, J., Gao, H. & Qiao, X. Low-frequency fiber bragg grating accelerometer based on diaphragm-type cantilever. Opt. Fiber Technol. 70, 102888 (2022).

Wang, X., Lee, Y. K. & Xu, W. Sensitivity and frequency response improvement of the micro thermal convective accelerometer with structure optimization. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 31(5), 753–759 (2022).

Xu, X. et al. Bandwidth optimization of MEMS accelerometers in fluid medium environment. Sensors 22(24), 9855 (2022).

Jiang, S., Wang, Y., Zhang, F., Sun, Z. & Wang, C. A high-sensitivity FBG accelerometer and application for flow monitoring in oil wells. Opt. Fiber Technol. 74, 103128 (2022).

Ritchie, J. M. & Wilkie, D. R. The dynamics of muscular contraction. J. Physiol. 143(1), 104–113 (1958).

Magnus, W. & Winkler, S. Hill’s equation, Dover Publication (INC. Mineola, 2013).

Hoppensteadt, F. C. Analysis and simulation of chaotic systems (Springer, 2013).

Ghanbari, M. & Rezazadeh, G. An electrostatically actuated microsensor for determination of microplar fluid physical properties. Meccanica 55, 2091–2106 (2020).

Valizadeh, M., Fathalilou, M. & Rezazadeh, G. Material dielectricity effects on the performance of capacitive micro-devices: A nonlinear study. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 19, 537–552 (2023).

Soltani, K., Fathalilou, M. & Rezazadeh, G. Development of an electrostatically actuated flowrate controller: Modelling and characterization. Int. J. Appl. Mech. 15(2), 2350008 (2023).

Rezazadeh, G. & Tahmasebi, A. M. Electromechanical behavior of microbeams with piezoelectric and electrostatic actuation. Sens. Imag. 10, 15–30 (2009).

Han, J. et al. Qualitative identification of the static pull-in and fundamental frequency of one-electrode MEMS resonators. Micromachines 6, 614 (2018).

Riks, E. An incremental approach to the solution of snapping and buckling problems. Int. J. Solids Struct. 15, 524–551 (1979).

Wempner, G. A. Discrete approximation related to nonlinear theories of solids. Int. J. Solids Struct. 17, 1581–1599 (1917).

Zhang, Y. et al. A novel design of a MEMS resonant accelerometer with adjustable sensitivity. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 379, 115859 (2024).

Varpula, A., Novikov, S., Sinkkonen, J. & Utriainen, M. Bias dependent sensitivity in metal-oxide gas sensor. Sens. Actuators A Chem. 131(1), 134–142 (2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G. Rezazadeh proposed the idea of the work. G. Rezazadeh and M. Ghanbari derived the governing equations, M.Fathalilou and M.Ghanbari got the numerical solutions and represented the results in figures, M.Ghanbari and H. Haddad Khodaparast prepared the manuscript, H. Haddad Khodaparast and G.Rezazadeh reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A

Appendix A

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghanbari, M., Fathalilou, M., Haddad Khodaparast, H. et al. Investigating nonlinear dynamic properties of an inertial sensor with rotational velocity-dependent rigidity. Sci Rep 15, 2006 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84264-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84264-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Nonlinear mechanics and parametric sensitivity of a displacement-dependent soft porous PDMS-based rectangular capacitive sensor: instability analysis

Journal of Umm Al-Qura University for Applied Sciences (2026)