Abstract

Habitual consumption of low-calorie sweeteners (LCS) during juvenile-adolescence can lead to greater sugar intake later in life. Here, we investigated if exposure to the LCS Acesulfame Potassium (Ace-K) during this critical period of development reprograms the taste system in a way that would alter hedonic responding for common dietary compounds. Results revealed that early-life LCS intake not only enhanced the avidity for a caloric sugar (fructose) when rats were in a state of caloric need, it increased acceptance of a bitterant (quinine) in Ace-K-exposed rats tested when middle-aged. These behavior shifts, which endured months after the end of Ace-K exposure, were accompanied by widespread changes in the peripheral taste system. The anterior tongue had fewer fungiform taste papillae, and the circumvallate papillae had a reduced anterior to posterior span and diminished expression of genes involved in sweet reception, sweet and bitter intracellular signaling, fructose transport, and cellular progeneration in the Ace-K-exposed rats. Ace-K exposure also led to a significant reduction in dopamine-producing cells of the ventral tegmental area. The collective findings reveal that LCS intake early in life alters the taste-brain axis and the behavioral responsiveness to both positive and negative tastants that are important determinants of dietary preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sensory input during critical stages of development is essential for establishing effective peripheral and central processing systems, including for vision, audition, olfaction, and touch1,2,3,4. Although early food experiences exert significant influence over lifelong food likes and eating habits5,6,7, how these formative environmental factors shape taste sensation and behavior remains enigmatic, especially compared to our understanding of the other basic senses. Diet is the major source of gustatory stimulation and a primary determinant of health throughout life. Prevalent diseases, such as diabetes and obesity, are directly linked to poor diets laden with simple sugar and fat, and overconsumption of these foods is driven in large part by their palatable tastes8. Children and adolescents are particularly prone to exceeding the FDA’s recommended daily sugar intake levels9. Human and rodent model data now provide ample evidence that chronically high amounts of sugar early in life impairs metabolic and cognitive fitness during adulthood10,11,12,13,14. Added sugar during critical developmental periods alters the appeal of sweet-tasting substances later on15,16 but see17, which points to a reprogramming of gustatory input and/or processing that could have further implications for lifelong dietary habits.

Low calorie sweeteners (LCS), which activate the same canonical sweet taste receptor as sugar and generate a similar hedonic sensation, namely sweet, are sometimes touted as a healthier alternative because they do not contribute much, if anything, in the way of calories. Yet, a recent study found that regular consumption of LCS-sweetened fluids during juvenile-adolescence in rats promotes greater ad libitum liquid sugar intake, and increases hedonic sensitivity to sugar-sweetened solutions in a short-term licking test18. Considering the gustatory system continues to mature well after weaning19,20,21, we hypothesized that LCS exposure during this developmental period fosters molecular and morphological changes to taste buds and the mesolimbic dopamine system, which promote heightened hedonic responsivity to sugar in adulthood. Ace-K is one of the main sweeteners approved for use in the United States and its consumption in food and beverage products has increased in recent decades22. Because of this, and because the previous study found that Ace-K exposure during the juvenile-adolescence phase in rats led to reductions in sweet receptor gene expression in taste tissue, sugar transporter gene expression in intestinal tissue, and alterations in plasticity-related signaling pathways in a key brain region in the mesolimbic dopamine system that receives gustatory input (the nucleus accumbens)18, we utilized this sweetener to investigate developmental effects of LCS use on taste function. Thus, in this study, we offered male and female rats Acesulfame potassium (Ace-K) just after weaning until late adolescence [postnatal day (PN) 26–77] to drink alongside water and their regular diet, and then we investigated changes in their taste-related behaviors, as well as in key processing sites along the taste-reward axis later in adulthood [PN > 210].

Results

Habitual consumption of Ace-K in juvenile-adolescence did not impact weight gain during this developmental period, nor did it influence body mass later in adulthood

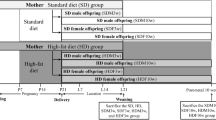

We initially offered rats 0.1% Ace-K at the FDA’s acceptable daily intake (ADI) levels (15 mg/kg) and water (LCS group) or just water (control group) to consume each day, along with ad libitum access to a regular chow diet, during their juvenile-adolescence period (postnatal day 26–77) (see Fig. 1A for experimental timelines). Young male and female rats strongly prefer this LCS solution to water, as confirmed in a separate subset of naïve rats (Fig. 1B, statistical outcomes in Table S1). Consistent with the prior study18, regular access to Ace-K, in addition to regular water and chow, did not impact weight gain during juvenile-adolescence in male and female rats (PN26-PN77, Fig. 1C; statistical test results in Table S2). Nor did it influence long term weight status, as the rats with a history of early life Ace-K intake remained similar in body mass to their control counterparts long into adulthood (PN210-225, Fig. 1C).

(A) Experimental timelines (Acesulfame potassium = Ace-K; postnatal day = PN); sample sizes listed represent the final N for each experiment. Lines not to scale. Note that one of the circumvallate histology cohorts underwent taste testing prior to harvest, but those results were presented elsewhere49. (B) Mean ± SEM cumulative water versus 0.1% Ace-K intake during a two bottle choice test at 24 h, and 48 h in a separate cohort of naïve rats at PN 57- 64 (n = 4 ♀; n = 4 ♂); inset figures show 30 min water vs 0.1% Ace-K intakes. (C) Mean body mass at the start (PN26) and end (PN77) of the juvenile-adolescence LCS exposure phase, and later just prior to taste testing (PN210-225) and/or tissue collection (PN218) in middle-aged female (F) and male (M) rats. Individual rats are shown as symbols. Values listed above the bars on PN77 indicate the mean percent weight gain during the Ace-K exposure phase. Control n = 22 (11♀; 11♂); Ace-K n = 21 (8♀; 13♂). * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001. Statistical outcomes are presented in Tables S1, S2. Schematics were created with Biorender.

Early-life Ace-K intake enhances the appeal of sugar taste and the acceptance of bitter taste later in adulthood

When they reached middle age (~ 7 months, beginning on postnatal day 210), we assessed hedonic evaluation of the caloric sugar, fructose, in a series of brief access taste tests in one subset of rats (Fig. 2A). Fructose was used as a representative sweet sugar for taste testing because (a) it is the most prominent source of added sugar in the Westernized diet and (b) other common sugars, like sucrose and glucose, engage sweet receptors and other known alternative sensing pathways that may contribute to their hedonic appeal23,24. Because there were no reliable effects or interactions involving male versus female in the overall test data (see statistical results in Table S3), the results are presented with sexes combined in Fig. 2, though average lick responses delineated by sex for each of the test sessions are shown in Fig. S1. Rats that had regularly consumed Ace-K early in life subsequently licked more avidly for fructose overall, and particularly at the three highest concentrations, when tested under fasted conditions (Fig. 2B). Moreover, this difference was apparent across all three test sessions conducted in the fasted state (Fig. S1 and Table S3). However, when rats were next tested under ad libitum fed conditions, Ace-K-exposed and control rats licked comparably for fructose, and this was evident on session 1 through 3 (Fig. 2D, see also Fig. S1). Rats initiated comparable numbers of trials, irrespective of a history with LCS and sex, on all fructose brief access taste tests (Fig. 2C and E).

(A) Schematic of the brief access taste test in the gustometer. (B, C) Mean ± SEM lick score and brief access trials initiated for fructose solutions in food-restricted (fasted) middle-aged rats previously exposed to a low-calorie sweetener (Ace-K) or water only (control, Con) during juvenile-adolescence. Symbols in panel C represent individual rats. (D, E) Mean ± SEM lick score and brief access trials initiated for fructose solutions in the same rats tested under ad libitum (fed) conditions. Symbols in panel E represent individual rats. (F, G) Mean ± SEM lick ratio and brief access trials initiated for a representative bitterant, quinine HCl, in the same rats (water restricted). Symbols in panel G represent individual rats. Control n = 12; Ace-K n = 11; * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01. Statistical outcomes are presented in Table S3. Schematics were created with Biorender.

Many LCS have other taste qualities; Ace-K, for instance, binds to bitter receptors and evokes a lingering bitter sensation at certain concentrations25. Evidence in humans suggests that exposure to bitter-tasting foods, like vegetables, early in life increases acceptance of this quality in foods and beverages later on26. Although it is unclear if the rats perceived bitterness in the 0.1% Ace-K offered during juvenile-adolescence, we nevertheless assessed if exposure to this LCS led to a higher tolerance for a representative bitter tastant, quinine, in a brief access taste test. Water-restricted rats with a history of Ace-K licked more for quinine solutions overall than their un-exposed counterparts over a similar number of self-initiated trials (Fig. 2F, G, see also Fig. S2). The collective results show that regular consumption of a LCS during juvenile-adolescence resulted in increased hedonic responding for the caloric sugar, fructose, when rats were in an energy deficit, and increased acceptance of a representative bitter compound when water-restricted.

Regular consumption of Ace-K during juvenile-adolescence leads to morphological changes in the major taste fields and significant reductions in sweet taste receptors and signaling intermediaries later in life

Taste signaling is responsive to diet throughout life27,28,29. For instance, access to highly concentrated sucrose for one month reduces neural responsivity to sucrose and downregulates the expression of proteins involved in G-protein coupled taste signaling in adult rats30. However, these effects were transient, likely because taste cells turnover every ~ 10 days on average, and signaling returns to normal after the added sugar regimen was discontinued. Diet during development appears to have more permanent effects on taste bud morphology and receptor expression31. We first assessed if LCS exposure altered the gross morphology of the major taste papillae and buds (Fig. 3A). We focused this analysis on male rats, as we did not see any consistent sex differences in body mass or behavior, and we had a more limited number of viable tissue samples from female rats. The statistical outcomes are shown in Table S4. Overall, we found that middle-aged male rats who had regularly consumed Ace-K during their juvenile-adolescence phase had fewer taste papillae on the anterior tongue (fungiform, Fig. 3B), and a smaller circumvallate (CV) field at the posterior tongue. These CV effects were characterized by a significantly reduced anterior to posterior expanse (Fig. 3C–E). The size of individual taste buds in the CV did not differ between diet groups, nor did the shape of these buds (Fig. 3F–I).

(A) Schematic of measurements taken for the circumvallate papillae (CV) and the fungiform papillae (FF) of Ace-K-exposed and control rats at PN218-270. (B) Mean number of taste papillae in the fungiform, Control n = 5; Ace-K n = 7. Symbols represent individual rats. (C–E) Mean CV length along the anterior to posterior axis, width, and trench depth. Symbols represent individual male rats. (F) Mean number of CV taste buds per section. Symbols represent individual male rats. (G–I) Mean CV taste bud height, width, and height to width ratio. Symbols represent individual male rats. * P ≤ 0.05. Statistical outcomes are presented in Table S4. Schematics were created with Biorender.

A previous study found reduced sweet receptor expression and glucose transporter expression in the circumvallate taste papillae of young adult female rats in the acute phase following access to LCS during juvenile-adolescence32. Thus, next, we assessed if exposure to LCS during juvenile-adolescence generated significant revisions to taste signaling profiles that lasted into mid-life (statistical outcomes in Table S4). The mRNA expression was significantly downregulated in Ace-K-exposed male and female rats for one gene (Tas1r3) and marginally, albeit not significantly less of the other gene (Tas1r2), that encode the sweet receptor proteins (Fig. 4A, B). Ace-K exposure also led to a reduction in Plcβ2, which is a critical intermediary in the G-protein coupled receptor pathways engaged by both sweet and bitter receptors (Fig. 4C). To confirm the reduction was also evident at the protein level, we performed immunofluorescence staining for PLCβ2 in the CVs of a subset of the rats in which fungiform taste buds were counted. This analysis showed that the Ace-K-exposed rats had a smaller proportion of PLCβ2-expressing cells in their taste buds than the control rats (Fig. 4G, H). Sglt1, involved in glucose transport into taste cells, was not affected by prior LCS exposure (Fig. 4D), but Glut5, which is involved in fructose transport, was dramatically reduced in the taste tissue of Ace-K-exposed rats (Fig. 4E). The results reveal significant reprogramming of the peripheral taste system that parallels changes in behavioral responding to sweet and bitter tastants in adulthood. Finally, in adult rodents, the sonic hedgehog (Shh) protein is expressed in the basal (stem) cells of the bud and contributes to the normal proliferation of these cells into mature taste cells. We found that the Ace-K-exposed rats expressed less Shh signal than the control rats, and, in fact, three rats in the LCS group did not have detectable levels of Shh in the CV (Fig. 4F). The collective findings show that rats that had regularly consumed an LCS early in life exhibit several molecular and morphological abnormalities in middle age that can impact function at the very first step of sensory processing.

(A–F) Mean mRNA expression levels of Tas1r2, Tas1r3, Plcb2, Sglt1, Glut5, and Shh in the CV. Symbols represent individual male and female rats. (G) Mean proportion of CV cells expressing the PLCβ2 protein per bud. Symbols represent individual male rats. (H) Representative images showing PLCβ2 staining in green in the CV of an Ace-K-exposed versus control rat. Scale bar = 20 µm. # P ≤ 0.05, one tailed, * P ≤ 0.05, ***P ≤ 0.005. Statistical outcomes are presented in Table S4.

Ace-K-exposed rats have fewer dopamine-producing neurons in the ventral tegmental area

Given Ace-K exposed rats were more responsive to sugar in the brief access taste test, we next investigated if there were compensatory changes in the mesolimbic dopamine system. We focused on the ventral tegmental area (VTA), which receives dense gustatory input, and houses the dopamine-producing neurons that project to regions involved in taste-motivated behaviors (e.g., nucleus accumbens)33,34,35,36. We found that early life Ace-K exposure led to a significantly impoverished population of neurons expressing tyrosine hydroxylase, an enzyme required for dopamine biosynthesis, in the VTA (Fig. 5A, B). We also assessed whether this was specific to the VTA. Neurons in the adjacent substantia nigra (SN) region also produce dopamine, but have not been implicated in taste function; rather, the SN appears to be part of a reward relay for signals arising from the gut37,38. Our analyses showed that a history with the LCS, Ace-K, early in life did not affect the dopamine-producing neurons in the SN (Fig. 5C, D).

(A and C) Mean number of cells expressing tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra (SN) for adult rats given prior regular access to Ace-K or water only (Con) during the juvenile/adolescence phase. Symbols represent individual rats. Control n = 7 (3♀; 4♂); Ace-K n = 6 (3♀; 3♂). (B and D) Representative images of TH + staining (in green) in the VTA and SN of rats exposed to Ace-K or water only. Scale bar = 100 µm. * P ≤ 0.05. Statistical outcomes are presented in Table S4.

Discussion

Diet has profound effects on development and, in turn, neurobehavioral functions throughout life, but the majority of studies have focused on the central metabolic and homeostatic consequences of these types of environmental factors. Taste is the primary sensory system linked to nutrition and plays a significant role in orchestrating our dietary choices. While it is well known that exposure to foods early in life can shape flavor preferences and acceptance later6,26,39,40,41, studies on the neurobiological mechanisms subserving these sensorial changes are limited. The present results revealed for the first time that LCS exposure during late postnatal developmental epochs (juvenile-adolescence) affects the taste end organ, the mesolimbic dopamine system, and taste-motivated behaviors. Early-life voluntary LCS consumption, kept within the FDA-recommended ADI limits, significantly altered the anatomy of the major taste fields, reduced key signaling intermediaries, reduced the expression of a dopamine precursor in the VTA, and enhanced the appeal of a caloric sugar under fasting conditions and increased tolerance of a normally avoided bitterant in middle-aged rats.

Voluntary LCS consumption during juvenile-adolescence increases sugar intake in adult rats18, but it was not clear whether this was due to alterations in taste processing per se. Here, we used a brief access taste test, which measures consummatory behaviors driven by the orosensory properties of a substance, to first assess how the history of access to a LCS impacted responding to a sweet caloric sugar, fructose, later in life. Ace-K-exposed rats licked significantly more for fructose than did the control rats, especially in the mid-high concentration range. However, this elevated attraction to fructose was only evident when the rats were tested in a fasted state during their first test with fructose. One possibility is that the effects of early life LCS exposure may emerge (or be otherwise more apparent) under conditions of physiological need. Indeed, metabolic state is known to modulate responsivity to taste stimuli via peripheral and central mechanisms42,43,44. Further, it appears that the control group’s responding to fructose gradually increased with repeated testing, eventually reaching the elevated levels observed in the Ace-K-exposed group. While this suggests that regular early life LCS exposure primes the sensitivity of the system for sugar later on, it also highlights how the gustatory system can be altered by experience in adulthood. Additional studies will be needed to more fully understand the durability of early life programming in the face of taste experiences later in life.

These behavioral changes were linked to significant alterations of the taste-brain axis. In the periphery, Ace-K-exposed rats exhibited significant reductions in the number of FF taste papillae and had a shorter CV, which putatively also reduced the receptive field. A previous study found that LCS exposure during the same developmental epoch led to a reduction in sweet receptor expression in young adulthood18. The present study extended this to reveal that blunted sweet receptor expression persisted into middle age and was coupled with reduced expression of its downstream signaling intermediary (Plcβ2), nearly 5 months after the last access to LCS. The same prior study found that loss of Tas1r2/3 was associated with reduced expression of the transceptor gene, Sglt1, in young adult female rats32. Here, we did not detect any statistical differences in Sglt1 expression in the taste bud cells, though if this effect is specific to females, we may have been underpowered in the present study. Glut5, which is a fructose transporter, was significantly reduced. Although this transporter has been located in rat taste cells and nerve fibers before, this is the first study, to our knowledge, to investigate if its expression in the circumvallate is regulated by diet, as it is in the intestines. We hypothesize that Glut5 or other aspects of fructose metabolism in the taste system may contribute to or otherwise complement oral sensibility of fructose by the sweet taste system (see more on this below). Correlative changes were seen in the central mesolimbic reward system, specifically at the level of the VTA. Ace-K exposed rats had fewer TH-expressing neurons in this region than the control rats.

On the surface, the wide-spread downregulation in key signaling intermediaries involved in the sensory-reward processing of taste is difficult to square with the behavioral hyper-responsiveness to fructose seen among the Ace-K-exposed rats. One possibility is that Ace-K-exposed rats require more fructose signal coming in, and hence more licking, to reach a hedonic threshold. A similar mechanism has been proposed for increased palatable food consumption and psychoactive substance administration when reward signaling is reduced (e.g.,45,46,47). The results provide the bases for future work designed to investigate whether the changes in taste related behavior, taste buds, and the VTA dopamine neuron population caused by early life Ace-K exposure are causally linked or orthogonal to one another, and/or whether other neural mechanisms (e.g., in the central processing of taste) are involved.

The history of Ace-K exposure also attenuated avoidance of the taste of quinine in the brief access test. The basis for this altered responsivity remains unclear, though some of the broader impacts on the taste end organ, including the reductions in the receptive capacity of the major taste fields, transcripts associated with G-protein-coupled signal transduction (i.e., Plcb2), and cellular proliferation (i.e., Shh) could contribute to a decreased sensitivity for bitter ligands. Future studies ought to also investigate if intake of these types of sweeteners directly affect bitter taste reception and, in turn, promote increased acceptance of bitter foods. Considering children and many adults do not consume enough cruciferous, vegetables, in part because they evoke bitter taste qualities, LCS may be one strategy, however paradoxical, to promote more vegetable intake.

Foods and beverages are complex stimuli, engaging multiple receptors, homeostatic, and metabolic signaling pathways as they are assimilated, which has made it difficult to decipher which dietary factors are responsible for shaping taste processing. A prior study found that rats raised with sucrose as their only source of fluid until PN ~ 70–75, licked in larger bursts for a sucrose solution (vs water) than did rats raised on regular water, suggesting that the early exposure enhanced acceptability of the sugar-sweetened solution48. In mice, Schiff et al.27 showed that exposure to solutions of varying chemosensory properties, including sucrose and a nutritional supplement Ensure, or just Ensure alone, over eight days during the juvenile-adolescence phase led to increased lick avidity for sucrose later on. However, follow up experiments revealed that these effects were due to ingestive experience with both the orosensory and caloric properties of the liquid diet, as neither exposure to a panel of calorie-free substances, including the LCS saccharin, nor exposure to Ensure via a feeding tube (bypassing oral receptors) were sufficient to alter the motivation to lick for sucrose in a subsequent brief access taste test. We found that early life exposure to a substance that engages sweet receptors but has minimal if any caloric benefit was sufficient to affect behavioral responding for fructose and quinine, modify the taste buds and a key central relay for taste-motivated behaviors, in a lasting way. We speculate that the longer and potentially greater LCS exposure over the ~ 50 days provided in the present study, as compared to the narrow (and intermixed) 2–8-day window in the Schiff et al.27 study accounts for this difference, but more work is needed to understand the critical variables (e.g., taste, postingestive effects, physiological condition, exposure timing) that train the developing the gustatory system.

LCS consumption is increasing, especially among juvenile and adolescent individuals. Our findings highlight the significant and long-lasting effects of these types of sweeteners encountered during these late, critical windows of development on taste function, which could ultimately lead to an increased proclivity for sugary and bitter substances later in life. Future studies are now needed to understand how other types of dietary factors, including sugars, other sweeteners, and mixed exposure to LCS and sugar, and whether dietary interventions across the lifespan influence taste function.

Materials and methods

Methods are reported in compliance with ARRIVE guidelines. All procedures were approved by Baldwin Wallace University.

Animals and LCS treatment

A total of 43 Sprague Dawley rats was used in this study series, and all underwent the same initial LCS (or control) exposure treatments (see Fig. 1A). Twenty-four rats were run in two replicate cohorts for behavioral brief access testing; rats from one of these cohorts were then also used for circumvallate gene expression qPCR analysis. Nineteen rats were used from three separate cohorts for tongue and brain histology; one of these cohorts underwent taste testing starting at PN 225, but these behavioral results were previously reported elsewhere49. For each cohort of rats, 2 male and 2 female pups between PN21-26 were taken from litters bred at Baldwin Wallace University (original breeding stock from Envigo) and divided between the experimental and control groups. All rats were singly housed in standard polycarbonate caging with corncob bedding and provided with non-edible enrichment. Standard rat chow (PMI5001) and reverse osmosis (RO) water were provided ad libitum except when noted. The rats in the experimental group were provided daily with 15 mg/kg of 0.1% (i.e., 1 mg/ml at 15 ml/kg) Acesulfame potassium (Ace-K; TCI Chemicals), which is an amount analogous to the US FDA-mandated maximum daily allowance of low-calorie sweeteners for intake by humans and as per Tsan et al.18. This standardized intake and limited it to a clinically relevant level. Each Ace-K dose was presented in a stainless-steel sipper spout (Ancare) that was suspended through the metal bars of the cage top and held in place with a stainless-steel chuck. The spouts were removed, rinsed with RO water, and dried daily before use for the current day’s dose. The rats in the control group received no supplement, though they were handled similarly. Ace-K provisions for the experimental group began on PN27 and ended PN77. To encourage consumption and combat neophobia, water bottles were removed from rats ~ 18 h prior to the first Ace-K provision and returned 1 h after Ace-K placement. This was repeated if any rat failed to drink their dose 2 days in a row; at no time was a rat fluid restricted for > 24 h. Experimenters confirmed that the entire dose was consumed at the end of each 24 h period. Any rat that did not fully consume its Ace-K dose after 24 h for a total of 5 times was removed from study, as was their brother or sister from the control group. Upon completion of the 50-day Ace-K access period, all rats remained conventionally housed with ad libitum food and water until ~ PN210 at which time experimental procedures began. All rats were humanely euthanized at the end of the studies with Euthasol (Virbac, AH, pentobarbital sodium and phenytoin sodium (390 mg, 50 mg/ml, 1–2 ml/kg, IP).

To confirm that adolescent rats could discriminate Ace-K at this concentration from water, we offered a separate cohort of naïve individually housed rats (derived from the same breeding stock as above) 0.1% Ace-K to consume from one bottle and regular deionized water to consume from another bottle on their home cage for 48 h. Rats were PN 57–64 at the start of the test. Bottles were weighed (to the nearest 0.1 g) after 30 min, 24 h, and 48 h of access. At the 24-h mark, the left–right position of the bottles on the home cage was switched (to prevent side bias effects). Ad libitum chow was available during the entire test.

All procedures were approved by and carried out in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines of Baldwin Wallace University.

Gustometer training and testing

A total of 24 rats in two cohorts were trained and tested to lick water and/or an array of fructose and then quinine concentrations during a brief access test in an automated gustometer (as per50). During the brief access task, rats can lick as little or as much as they choose during each trial, and they can initiate as many trials as they choose. Their unconditioned licking during each trial is a measure of the consummatory responses elicited by the taste stimulus contacting receptors and serves as an index of their hedonic responsivity, and the number of trials they initiate is a measure of appetitive responding relating to the motivational value of the stimulus. All solutions used during testing were made fresh daily from reagent grade chemicals dissolved in RO water and presented at room temperature.

Rats of both the control and experimental groups were trained in once-daily 30-min sessions under water-restricted conditions to lick water (4 sessions) and then water plus an array of 5 fructose (Sigma Aldrich) concentrations (1 session) when a spout was presented in 10-s trials. We then across 3 sessions measured the number of licks to water and each of the 5 fructose concentrations during trials and the number of trials initiated overall while the rats were in a food-restricted state. Food was removed ~ 18 h prior to each session and was returned ad libitum to the rats 1 h after testing for overnight feeding; thus, testing occurred every-other day. After testing and > 48 h of re-feeding, the rats were tested across 3 sessions every-other day during free-fed conditions. A lick score was calculated for each fructose concentration, which shows the average number of licks taken at each fructose concentration across the 3 days minus each rat’s average licks of water during testing in each condition. During food-restricted testing of the 2nd cohort, one male rat from the LCS group failed to lick fructose in a concentration dependent manner for unknown reasons, rendering data that were statistical outliers from the rest of the group and the previous experimental cohort. Thus, the rat was removed from the experiment and its behavioral data were excluded from analyses, but the taste tissue was used in mRNA analyses (see below).

The week after the rats used to measure lick scores and trial-taking to fructose completed testing, they were under water-restricted conditions allowed to lick water (1 session) and then water plus an array of 5 quinine concentrations (2 sessions) in the brief access paradigm. Testing occurred every-other day, with water removal ~ 18 h prior to testing and water return 1 h after testing and each session separated by an overnight rehydration period of ~ 30 h. A lick ratio was calculated for each quinine concentration that shows the average number of licks taken at each quinine concentration across the 2 days divided by each rat’s average licks of water during testing under water-restricted conditions. Lick ratio was used for quinine instead of lick score, as used for fructose, because, since quinine is normally avoided, lick ratio allows assessment of how much the rat is willing to consume in its thirsty state despite adulteration of the offered fluid with a bitter tastant.

Circumvallate extraction and real time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

On PN 243, each rat from the second behavioral cohort was given a lethal overdose of Euthasol (Virbac, AH, pentobarbital sodium and phenytoin sodium (390 mg, 50 mg/ml, 1–2 mL/kg, IP). The whole tongue was then rapidly excised and 1.5 mL of an enzymatic cocktail containing 1 mg/mL collagenase A and 0.1 mg/mL elastase (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS was injected under the circumvallate papillae (CV). The tongue was placed in oxygenated Tyrode’s solution for 20 min, before the CV was gently peeled from the underlying connective tissue. The CV was stored in RNALater® (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 4 °C overnight and then transferred to DNase/RNase-free tubes and stored at –80 °C until processing.

To quantify relative mRNA expression levels of several genes of interest, quantitative PCR (qPCR) were performed on CV of rats exposed to LCS during juvenile and adolescence (n = 6; 3♀ and 3♂) versus control (n = 6; 3♀ and 3♂), according to our previously published protocol18. Total RNA was extracted from each sample with the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (74804, Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized with the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (205311, Qiagen) and amplified using the TaqMan PreAmp Master Mix (4391128, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time PCR was measured with the TaqMan Gene Expression Assays from Applied Biosystems — for rat β-actin (Actb, Rn00667869_m1), rat Taste receptor type 1 member 3 (Tas1r3, Rn00590759_g1), rat Taste receptor, type 1, member 2 (Tas1r2, Rn01515494_m1), rat Phospholipase C beta 2 (PLCβ2, Rn00585063_m1), rat Sglt1 (Slc5a1, Rn01640634_m1), rat Glut5 (Slc2a5, Rn00582000_m1), and rat Sonic Hedgehog (Shh, Rn00568129_m1)— and TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (4444557, Applied Biosystems), in the Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reactions were run in triplicate and control wells that did not contain cDNA template were included to confirm no genomic DNA contamination. Triplicate Ct values for each sample were averaged and normalized to β-actin expression. Relative gene expression levels were quantified using the comparative 2–ΔΔCt method. One female from the Ace-K-exposed group was determined to be a statistical outlier for Plcb2, Sglt1, and Glut5, and was thus excluded from statistical analyses. CT values for Shh could not be determined for three Ace-K-exposed rats.

Histology and immunofluorescence staining

Tongues were collected from a total of 19 rats across 3 cohorts to assess (1) the size of the circumvallate taste field and morphology of the taste buds therein and (2) the number of taste pores in the fungiform taste field of the anterior tongue. Because we only had a limited number of viable tongue tissues from female rats (n = 4), statistical analyses were performed only on CV and FF data from male rats (n = 6–15, sample sizes are provided in the figure legends). Rats from 1 of the three cohorts had been previously tested in a brief access test and psychophysical detection paradigm using fructose, which was reported elsewhere (Mathes et al.49, n = 5 male rats); all other rats were untested behaviorally (n = 10 male rats). A subset of randomly selected brains from male and female of this untested group were included in the brain analyses. Rats were given a lethal injection as described above and, once no longer reflexive, transcardially exsanguinated with chilled PBS followed by perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution. Tongues and brains were removed and post-fixed overnight at 2 °C in a solution of 20% sucrose in PFA, after which they were stored at 2 °C in a solution of 20% sucrose in PBS. Brains were subsequently frozen for cryosectioning (see below).

The portion of the tongue including the circumvallate papillae (e.g., posterior to the intermolar eminence) was sliced coronally at a thickness of 20 µm on a cryostat, and sections were collected electrostatically on slides and stored at − 80 °C. The slices were Nissl stained using a standard Hemotoxylin and Eosin protocol, and the slides were coverslipped with Toluene-based media. The slices were analyzed at 10× magnification to determine the total that contained taste buds, which we defined as the span of the CV taste field. We counted the number of taste buds in slices at 25% and 75% through the field at 10× magnification and averaged these two counts. The heights and widths of each taste bud on the same 25% and 75% slices were measured in micrometers (µm) using ImageJ and were averaged together. CV widths were measured from the start of one trench to the other in micrometers (µm) using ImageJ. CV trenches were measured from the top to deepest part of the trench on both the left and right side of each trench. The trenches were measured on the same slices mentioned above, measured in micrometers (µm) using ImageJ, and averaged together. One control rat was excluded from the circumvallate width analysis as it was a statistical outlier. Taste bud counts and size for one male rat in the experimental group were unable to be attained due to damage to the tissue; however, CV anterior to posterior span, width, and trench height for that animal were still determinable.

A subset of these coronal sections (2 per rat, at approximately 25% and 75% through the CV taste field, n = 3/group, all male) were processed to visualize PLCβ2 with immunofluorescence. Briefly, sections were blocked for 1 h in 5% donkey serum, and then incubated in rabbit anti-PLCβ2 (Q-15) (sc-206, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:200) overnight at room temperature. Sections were rinsed in PBS (× 5) incubated in Alexa Fluor 488 (A21206, Invitrogen, 1:500) for 2 h, and then coverslipped with the Vectashield mounting medium to visualize DAPI. Slides were examined at 60× using a Nikon Eclipse Ti confocal microscope, and digital images of each area were captured with a Nikon C2 camera and NIS Elements software. The number of cells (as determined by DAPI-stained nuclei) and the number of PLCβ2-expressing cells within each taste bud were quantified, and then averaged across the two sections per rat.

The dorsal portion of the tongue including the fungiform papillae (e.g., anterior to the intermolar eminence) was separated from the underlying tissue, stained with 0.5% methylene blue, and flattened between two microscope slides. Photographs of the tissue were taken at 4× magnification in a serpentine grid pattern, and the number of taste papillae were counted to provide a proxy of number of taste buds (1 bud per papillae).

Fixed brains were cryosectioned through the midbrain at 20 µm, and sections were collected electrostatically on slides and stored at − 80 °C. An anatomically matched section from each rat that included the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra (SN) was selected for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunostaining. For TH immunohistochemical processing, primary and secondary antisera were diluted in 0.3% Triton X-100 and 5% normal donkey serum. Slide-mounted sections were washed with PBS at room temperature, blocked for 1 h in 5% donkey serum, and incubated overnight at room temperature with sheep anti-TH primary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich; catalog # AB1542, 1:500). Slides were then washed in PBS (×5), followed by a 2-h incubation at room temperature with donkey anti-sheep Alexa Fluor 488 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc.; catalog # 713-546-147, 1:500). Slides were rinsed with PBS (×5), followed by a 20-min incubation at room temperature with NeuroTrace 530/615 Red Fluorescent Nissl Stain (Invitrogen, N21482, 1:250). Slides were washed in PBS (3×), then coverslipped using Fluoromount-G Mounting Medium, with DAPI (Invitrogen, 00-4959-52). Slides were examined at 20× using a Nikon Eclipse Ti epifluorescence microscope, and digital images of each area were captured with a Hamamatsu digital camera and NIS Elements software. ImageJ was used to quantify TH immunoreactivity bilaterally in the VTA and SN. Threshold criteria based on optical density, object shape, and object size were used to identify TH-positive cells within the boundaries of each region as defined by Paxinos and Watson’s (2014) rat brain atlas 7th edition51.

All data collection was performed by experimenters who were blind to the group and sex (where possible) of the animal that provided the tissue.

Statistical analyses

Mean ± SEM or individual data points are presented in each figure, graphed and analyzed with Graphpad Prism (version 7) or Statistica (version 11). Body mass and the number of brief access taste trials initiated in each behavioral test were separately analyzed in factorial ANOVAs, with diet treatment (LCS versus control) and sex (female versus male) as factors. Due to significant effects of sex on body mass, separate post hoc independent samples t-tests were used to determine effects of diet treatment at all ages of interest for each sex. Concentration-dependent lick scores or ratios for fructose and quinine were assessed with repeated measures ANOVAs, with diet, sex, and concentration as factors. To follow up on significant interactions involving concentration or developmental exposure condition (diet), pairwise independent sample t-tests were used at each concentration, and p values were Bonferroni-corrected to avoid Type I errors. Water and Ace-K intake in the two bottle tests was analyzed with paired samples t-tests. Histological, immunofluorescence, and mRNA measures were all analyzed with independent samples t-tests (two-tailed), except that a one-tailed t-test was used to test the a priori directional hypothesis that PLCβ2 protein levels were reduced in Ace-K-exposed rats.

Data availability

Source data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Cummings, D. M. & Belluscio, L. Continuous neural plasticity in the olfactory intrabulbar circuitry. J. Neurosci. 30(27), 9172–9180 (2010).

Hubel, D. H., Wiesel, T. N. & LeVay, S. Plasticity of ocular dominance columns in monkey striate cortex. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 278(961), 377–409 (1977).

Di Marco, S., Nguyen, V. A., Bisti, S. & Protti, D. A. Permanent functional reorganization of retinal circuits induced by early long-term visual deprivation. J. Neurosci. 29(43), 13691–13701 (2009).

Rauschecker, J. P., Tian, B., Korte, M. & Egert, U. Crossmodal changes in the somatosensory vibrissa/barrel system of visually deprived animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89(11), 5063–5067 (1992).

Mennella, J. A., Daniels, L. M. & Reiter, A. R. Learning to like vegetables during breastfeeding: a randomized clinical trial of lactating mothers and infants. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 106(1), 67–76 (2017).

Mennella, J. A., Forestell, C. A., Morgan, L. K. & Beauchamp, G. K. Early milk feeding influences taste acceptance and liking during infancy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 90(3), 780s–788s (2009).

Mennella, J. A. & Beauchamp, G. K. Flavor experiences during formula feeding are related to preferences during childhood. Early Hum. Dev. 68(2), 71–82 (2002).

Bray, G. A. & Popkin, B. M. Dietary sugar and body weight: have we reached a crisis in the epidemic of obesity and diabetes? Health be damned! Pour on the sugar. Diabetes Care 37(4), 950–956 (2014).

Ervin, R. B., Kit, B. K., Carroll, M. D. & Ogden, C. L. Consumption of added sugar among U.S. children and adolescents, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief 2012(87), 1–8 (2012).

Vos, M. B. et al. Added sugars and cardiovascular disease risk in children: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation 135(19), e1017–e1034 (2017).

Cantoral, A. et al. Early introduction and cumulative consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages during the pre-school period and risk of obesity at 8–14 years of age. Pediatr. Obes. 11(1), 68–74 (2016).

Cohen, J. F. W., Rifas-Shiman, S. L., Young, J. & Oken, E. Associations of prenatal and child sugar intake with child cognition. Am. J. Prevent. Med. 54(6), 727–735 (2018).

De Cock, N. et al. Sensitivity to reward is associated with snack and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in adolescents. Eur. J. Nutr. 55(4), 1623–1632 (2016).

Noble, E. E., Hsu, T. M., Liang, J. & Kanoski, S. E. Early-life sugar consumption has long-term negative effects on memory function in male rats. Nutr. Neurosci. 22(4), 273–283 (2019).

Beauchamp, G. K. & Moran, M. Acceptance of sweet and salty tastes in 2-year-old children. Appetite 5(4), 291–305 (1984).

Pepino, M. Y. & Mennella, J. A. Factors contributing to individual differences in sucrose preference. Chem. Senses 30(Suppl 1), i319–320 (2005).

Wurtman, J. J. & Wurtman, R. J. Sucrose consumption early in life fails to modify the appetite of adult rats for sweet foods. Sci. (N. Y., N.Y.) 205(4403), 321–322 (1979).

Tsan, L., Chometton, S., Hayes, A. M. et al. Early-life low-calorie sweetener consumption disrupts glucose regulation, sugar-motivated behavior, and memory function in rats. JCI insight 7, 20 (2022).

Hosley, M. A. & Oakley, B. Postnatal development of the vallate papilla and taste buds in rats. Anatom. Rec. 218(2), 216–222 (1987).

Mangold, J. E. & Hill, D. L. Postnatal reorganization of primary afferent terminal fields in the rat gustatory brainstem is determined by prenatal dietary history. J. Comp. Neurol. 509(6), 594–607 (2008).

Lasiter, P. S. Postnatal development of gustatory recipient zones within the nucleus of the solitary tract. Brain Res. Bull. 28(5), 667–677 (1992).

Sylvetsky, A. C. et al. Consumption of low-calorie sweeteners among children and adults in the United States. J. Acad. Nutr. Dietet. 117(3), 441–448.e442 (2017).

Chometton, S. et al. A glucokinase-linked sensor in the taste system contributes to glucose appetite. Mol. Metabol. 64, 101554 (2022).

Yasumatsu, K. et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 as a sugar taste sensor in mouse tongue. Acta Physiol. (Oxf., Engl.) 230(4), e13529 (2020).

Horne, J., Lawless, H. T., Speirs, W. & Sposato, D. Bitter taste of saccharin and acesulfame-K. Chem. Senses 27(1), 31–38 (2002).

Forestell, C. A. & Mennella, J. A. Early determinants of fruit and vegetable acceptance. Pediatrics 120(6), 1247–1254 (2007).

Schiff, H. C. et al. Experience-dependent plasticity of gustatory insular cortex circuits and taste preferences. Sci. Adv. 9(2), eade6561 (2023).

Contreras, R. J. & Frank, M. Sodium deprivation alters neural responses to gustatory stimuli. J. Gener. Physiol. 73(5), 569–594 (1979).

Stewart, R. E., Lasiter, P. S., Benos, D. J. & Hill, D. L. Immunohistochemical correlates of peripheral gustatory sensitivity to sodium and amiloride. Acta Anatom. 153(4), 310–319 (1995).

Sung, H. et al. High-sucrose diet exposure is associated with selective and reversible alterations in the rat peripheral taste system. Curr. Biol. 32(19), 4103–4113.e4104 (2022).

Hendricks, S. J., Brunjes, P. C. & Hill, D. L. Taste bud cell dynamics during normal and sodium-restricted development. J. Comp. Neurol. 472(2), 173–182 (2004).

Chometton, S., Tsan, L., Hayes, A. M. R., Kanoski, S. E. & Schier, L. A. Early-life influences of low-calorie sweetener consumption on sugar taste. Physiol. Behav. 264, 114133 (2023).

Roitman, M. F., Wheeler, R. A. & Carelli, R. M. Nucleus accumbens neurons are innately tuned for rewarding and aversive taste stimuli, encode their predictors, and are linked to motor output. Neuron 45(4), 587–597 (2005).

Loh, M. K., Hurh, S., Bazzino, P. et al. Dopamine Activity Encodes the Changing Valence of the Same Stimulus in Conditioned Taste Aversion Paradigms (eLife Sciences Publications Ltd, 2024).

Boughter, J. D. Jr., Lu, L., Saites, L. N. & Tokita, K. Sweet and bitter taste stimuli activate VTA projection neurons in the parabrachial nucleus. Brain Res. 1714, 99–110 (2019).

Hajnal, A., Smith, G. P. & Norgren, R. Oral sucrose stimulation increases accumbens dopamine in the rat. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Compar. Physiol. 286(1), R31–R37 (2004).

Han, W. et al. A neural circuit for gut-induced reward. Cell 175(3), 665–678.e623 (2018).

Tellez, L. A. et al. Separate circuitries encode the hedonic and nutritional values of sugar. Nat. Neurosci. 19(3), 465–470 (2016).

Mennella, J. A. Ontogeny of taste preferences: basic biology and implications for health. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 99(3), 704s–711s (2014).

Spahn, J. M., Callahan, E. H., Spill, M. K. et al. Influence of maternal diet on flavor transfer to amniotic fluid and breast milk and children’s responses: a systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 109(Suppl_7), 1003s–1026s (2019).

Mezei, G. C., Ural, S. H. & Hajnal, A. Differential effects of maternal high fat diet during pregnancy and lactation on taste preferences in rats. Nutrients 12, 11 (2020).

Berridge, K. C. Modulation of taste affect by hunger, caloric satiety, and sensory-specific satiety in the rat. Appetite 16(2), 103–120 (1991).

Konanur, V. R., Hurh, S. J., Hsu, T. M. & Roitman, M. F. Dopamine neuron activity evoked by sucrose and sucrose-predictive cues is augmented by peripheral and central manipulations of glucose availability. Eur. J. Neurosci. (2023).

Cone, J. J., McCutcheon, J. E. & Roitman, M. F. Ghrelin acts as an interface between physiological state and phasic dopamine signaling. J. Neurosci. 34(14), 4905–4913 (2014).

Stice, E., Spoor, S., Bohon, C. & Small, D. M. Relation between obesity and blunted striatal response to food is moderated by TaqIA A1 allele. Sci. (N. Y., N.Y.) 322(5900), 449–452 (2008).

Thanos, P. K. et al. DRD2 gene transfer into the nucleus accumbens core of the alcohol preferring and nonpreferring rats attenuates alcohol drinking. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 28(5), 720–728 (2004).

Ahmed, S. H., Kenny, P. J., Koob, G. F. & Markou, A. Neurobiological evidence for hedonic allostasis associated with escalating cocaine use. Nat. Neurosci. 5(7), 625–626 (2002).

Volcko, K. L., Brakey, D. J., Przybysz, J. T. & Daniels, D. Exclusively drinking sucrose or saline early in life alters adult drinking behavior by laboratory rats. Appetite 149, 104616 (2020).

Mathes, C. M. & Schier, L. A. Early-life exposure to a non-nutritive sweetener increases unconditioned licking for fructose with some impact on psychophysically assessed fructose detectability by adult male and female rats. In Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for the Chemoreception Sciences, Bonita Springs (2023).

Markison, S., St John, S. J. & Spector, A. C. Glossopharyngeal nerve transection reduces quinine avoidance in rats not given presurgical stimulus exposure. Physiol. Behav. 65(4–5), 773–778 (1999).

George Paxinos, C. W. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (Springer, 2013).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DC018562 to LAS), the University of Southern California Diabetes and Obesity Research Institute pilot award (to LAS), Baldwin Wallace University Faculty Development Funds (to CMM and DRH), Baldwin Wallace University Summer Scholar award (to CMM and GM), the Lauria STEM Research Scholarship (to CMM and MJW), an Ohio Space Grant Consortium Scholarship (to EGG), and an Undergraduate Research Grant and the Mickley Award from Nu Rho Psi: the National Honors Society in Neuroscience (to JPT-B). We appreciate protocol guidance for counting fungiform taste papillae provided by Dr. Yada Treesukosol. Some graphics were created with Biorender, with permission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LAS, SJT, and CMM conceptualized and designed experiments, analyzed data, interpreted results, and drafted the manuscript. CMM, SC, JPT-B, EGG, GM, MJW, DRH, BMA, and SJT performed experiments, data acquisition, and analyses.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mathes, C.M., Terrill, S.J., Taborda-Bejarano, J.P. et al. Neurobehavioral plasticity in the rodent gustatory system induced by regular consumption of a low-calorie sweetener during adolescence. Sci Rep 15, 2359 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84391-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84391-3