Abstract

Chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and Apricot (Prunus armeniaca) both are economically and nutritionally important, these both faces severe losses due to fungal Infections. For several fungal infections, traditional methods of management rely on chemical fungicideswhich have environmental and health risks. The in-vitro antifungal efficacy of myco-synthesized and bacteria-synthesized zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles against pathogens impacting chickpea and apricot is aimed to be compared in this review article. Evaluated for their antifungal effectiveness against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris in chickpea and Alternaria solani, myco-synthesized ZnO NPs generated from Trichoderma harzianum and bacteria-synthesized ZnO NPs were using a poisoned food approach, the study evaluated minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC), and inhibition zone diameter. At lower concentrations, myco-synthesized ZnO NPs shown better antifungal activity than their bacteria-synthesized counterparts, according to results. Surface changes, size, and concentration of nanoparticles were main determinants of antifungal activity. Emphasizing the need of more study to maximize the synthesis and application in agricultural environments, this review underlines the possibilities of ZnO NPs as sustainable substitutes for chemical fungicides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, both nutritionally and economically, chickpea and apricot are rather valuable crops. Essential elements including lipids, proteins, carbs, and minerals make chickpea (C. arietinum) a crucial pulse crop that a major supply of vegetarian protein for both humans and animals. With F. oxysporum a main pathogen, several biotic variables greatly influence the yield of chickpea, especially fungal diseases such Ascochyta blight and Fusarium wilt1. Up to six years of persistence in the soil allows this soil-borne fungus to cause yield losses ranging from 10 to 90% worldwide, and up to 100% under suitable conditions2. Once inside the plant’s vascular system, the infection causes wilting and finally death. Member of the Rosaceae family, apricot (Prunus armeniaca) is extensively grown for its sweet and nutritious fruit, high in vitamins A and C, fibre, and antioxidants3. Still, many fungal infections also endanger apricot output. Important diseases that lower fruit quality and yield are brown rot brought on by Monilinia spp. and powdery mildew brought on by Podosphaera spp4. Furthermore, well-known to cause significant post-harvest losses are Alternaria genus species, especially Alternaria solani, which generates extremely harmful mycotoxins for human health5. Conventional techniques for managing fungal diseases in crops such as apricot and chickpea comprise cultural measures, fungicides, and the elimination of diseased plant material6. Among the cultural activities are crop rotations, resistant cultivars, and correct field cleanliness. Though their lingering toxicity causes hazards to human health and the environment, chemical fungicides are extensively used7. Furthermore, of great worry is the emergence of pesticide resistance among diseases. A creative and sustainable method of controlling fungal diseases in agriculture is presented by nanotechnology8. Because of their special qualities, including high surface to volume ratio, which improves their reactivity, zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) have showed promise as strong antifungal agents9. Through their disruption of cell membranes and generation of reactive oxygen species, these nanoparticles can stop fungal development10. Moreover, environmentally benign biological approaches including microorganisms like bacteria and fungus allow one to synthesis ZnO NPs11. Effective and biocompatible substitutes for conventional chemical fungicides are mycosynthesized nanoparticles made from fungus such as T. harzianum and bacteria-synthesis produced nanoparticles12. These techniques not only lower environmental impact but also increase the stability and effectiveness of the nanoparticles.

History of nanotechnology

Richard P. Feynman was a first scientist who created the idea of nanotechnology during his well-known speech on the bottom in Caltech in 195913. The term nanotechnology was coined by a Japanese scientist Norio Taniguchi in 197414. An American MIT physicist Kim Eric Drexler was a first scientist who gave the theory of nanotechnology conceptually and talked about the magic of nanoparticles in 1980s15. Nanotechnology has been expanded in scientific field like biological, physical, medical and environmental sciences16. Nanotechnology finds applications in various fields, including the development of biosensors for manufacturing, biomedical products, renewable energy, and environmental management17. Nano-structures, which can be metallic or non-metallic, are integral to innovative applications like thin films, nanospheres, nanorods, and other nanoparticles18. Nanotechnology can be defined as the manipulation and control of materials, structures, devices, or systems at the nanometer scale one billionth of a meter19. This technology allows for the creation, characterization, and deployment of materials with precise shapes and sizes at the nanoscale20. It operates at chemical, molecular, and supramolecular levels to develop new materials, structures, tools, and systems with enhanced physical, chemical, and biological properties21. Nanotechnology is used to identify and control these nanoscale characteristics, leading to significant advancements in various phenomena and processes22.

History of Zn nanoparticles

The term “nano” comes from the Greek word for “dwarf,” signifying something extremely small, specifically one billionth of a meter (10⁻⁹)23. Nanoparticles (NPs) are materials, including metals, ceramics, polymers, and composites, that exist at the nanometer scale, typically ranging from 1 to 100 nm24. These nanoparticles exhibit unique optical, chemical, and mechanical properties due to quantum effects and a high surface-area-to-volume ratio, which differentiate them significantly from their bulk counterparts25. Zinc nanoparticles, particularly zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles, have been increasingly utilized in various fields due to their distinctive properties, such as UV absorption, photocatalytic activity, and antibacterial effects26. Historically, zinc compounds have been used for centuries, with zinc oxide being a key component in medicinal ointments and skin protectants, such as calamine lotion, since ancient times27. The use of zinc to treat skin conditions can be traced back to ancient Egypt and Greece, where zinc-containing compounds were applied to wounds and burns28. The modern scientific exploration of ZnO nanoparticles began in the late twentieth century, as advancements in nanotechnology allowed for the precise manipulation and synthesis of zinc at the nanoscale29. These advancements unlocked new potential for ZnO NPs in applications like sunscreens, where their ability to block harmful UV rays while remaining transparent on the skin made them highly desirable30. ZnO nanoparticles also became integral in the development of various consumer goods, including cosmetics, textiles, and paints, where their antimicrobial properties were particularly valued. In the food industry, ZnO NPs were explored for use in food packaging to enhance preservation and prevent spoilage31. Their role in environmental protection has also been significant, with ZnO nanoparticles being used in water purification systems and as photocatalysts for the degradation of pollutants32. The widespread adoption of ZnO nanoparticles has been driven by their versatility and the continued interest in nanotechnology33. Research on ZnO nanoparticles has expanded rapidly, exploring their potential in fields such as biomedicine, where they are being tested for drug delivery systems and cancer therapies, as well as in electronics for the development of advanced semiconductors and sensors34. Zinc’s long-standing use in traditional medicine, coupled with the modern advancements in nanotechnology, has solidified ZnO nanoparticles as a critical component in a wide range of scientific and industrial applications35. The ongoing study of zinc at the nanoscale continues to reveal new opportunities for innovation, ensuring that zinc nanoparticles will remain a vital part of technological progress in the coming years36.

ZnO NPs: attributes

The functionalities features of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) synthesized by bacterium and myco-synthesis are make them efficient against plant diseases37. Bacteria-synthesis of ZnO NPs utilizing bacterial cultures (reducing and stabilizing agents)38. Through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) including superoxide anions, hydroxyl radicals, and hydrogen peroxide that damage bacterial cell walls and increase membrane permeability thereby inducing cell death which can be attributed mainly to their vast antibacterial potential39. Importantly these ZnO NPs bacteria-synthesized were further found to be biocompatible and environmentally safe for utilizing in agriculture that would not risk the environment or plants40. In the myco-synthesis of ZnO NPs by utilizing fungal extracts for both reducing and stabilizing agents which were reported41. The nanoparticles possess strong antifungal and antibacterial properties (Fig. 1), which destroy the cell membranes of fungi/bacteria by generating ROS or releasing zinc ions in this manner interfere on cellular processes42. This essentially provides the morpho-functional differences at ZnO NPs generated via fungal route which is possibly enhanced for their antibacterial properties with distinct functional groups on its surface area43. Similar to bacteria-synthesized ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs), these particles are both biocompatible and environmentally friendly44. They have been shown to boost the activity of photosynthetic pigments, carbohydrates, proteins, and antioxidant enzymes, thereby promoting plant growth45. Both types of ZnO NPs present a promising alternative to traditional chemical pesticides due to their low phytotoxicity and targeted antibacterial properties46. This not only enhances agricultural productivity but also minimizes environmental impact47.

Importance of zinc nanoparticles

Zinc plays a crucial role in many biological processes and is known for its moderate conductivity and resistance48. In nature, zinc is most commonly found in the Zn+2 oxidation states, which is both stable and abundant. Due to its essential biological functions, zinc is often used to treat conditions like diarrhea, Wilson’s disease, and various skin disorders49. As zinc continues to find new applications, especially in electronics and healthcare, the demand for this versatile metal is expected to increase, driving global production trends as the industry expands50. Zinc nanoparticles possess antimicrobial properties, serve as chemical reaction catalysts, and are used in UV protection, sensors, and energy storage devices51. These nanoparticles are employed in drug delivery systems, medical imaging, biosensing, and air purification technologies52. They are valuable in biomedical applications, including diagnostics, wound healing, and cancer treatment, due to their selective toxicity and therapeutic potential34. Zinc nanoparticles are used in coatings for medical devices, such as stents and implants, and in environmental remediation efforts53. Zinc nanoparticles are effective in environmental remediation, particularly in water treatment processes where they help in removing contaminants like heavy metals and organic pollutants. Their photocatalytic properties make them ideal for degrading harmful substances in wastewater54. In agriculture, zinc nanoparticles are used to enhance plant growth and increase crop yields. They serve as micronutrient fertilizers that are more efficiently absorbed by plants, promoting better nutrition and resistance to diseases55. Zinc nanoparticles are widely used in cosmetics, especially in sunscreens and skincare products. Their ability to block harmful UV rays while being less likely to cause skin irritation makes them a popular ingredient for sun protection and skin soothing products56. Zinc nanoparticles are being explored in the food industry for their antimicrobial properties, which help in extending the shelf life of packaged foods by preventing microbial growth57. In textiles, zinc nanoparticles are incorporated into fabrics to provide antimicrobial and UV-protection properties. This application is particularly useful in medical textiles, sportswear, and clothing for outdoor activities. Zinc nanoparticles are also used in the development of more efficient batteries and electronic components58. Their ability to enhance the performance of energy storage devices is critical in the advancement of portable electronics and electric vehicles59. Zinc nanoparticles are being researched for their potential in cancer treatment, particularly in targeted drug delivery systems where they can help deliver drugs directly to cancer cells, reducing side effects and increasing treatment efficacy34. In the manufacturing and construction industries, zinc nanoparticles are used in anti-corrosion coatings to protect metal surfaces from rust and degradation, extending the lifespan of machinery, vehicles, and infrastructure60.

Comparison of zinc oxide nanoparticles with other NPs

Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) possess distinct optical and electronic characteristics that set them apart from other nanoparticles such as titanium dioxide (TiO₂) and silver oxide (AgO)61. ZnO NPs are notable for their wide bandgap and high exciton binding energy, which enhance their UV absorption and photostability26. These properties make them highly effective as UV-blocking agents and photocatalysts62. Unlike silver oxide and gold nanoparticles, which are valued for their plasmon resonance properties, ZnO NPs do not exhibit surface plasmon resonance63. Nevertheless, ZnO NPs are preferred in optoelectronic applications due to their efficient light emission and their ability to generate reactive oxygen species under UV light, which is beneficial for photodynamic therapy and antimicrobial treatments64. Additionally, ZnO NPs offer significant benefits in biosensing applications65. Their high isoelectric point enables effective interaction with proteins, making them ideal for enzyme immobilization and biosensor development66. Compared to gold nanoparticles, ZnO NPs provide superior chemical stability and lower toxicity, which are essential for biomedical applications36. Additionally, ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) exhibit strong fluorescence, especially in the blue and UV spectra, making them ideal for bio-imaging and as luminescent markers67. The fluorescence properties of ZnO NPs can be modified by altering the particle size and doping with other elements, offering a level of versatility not easily achieved with other metal oxide nanoparticles68. Compared to silver oxide nanoparticles, ZnO NPs show superior photocatalytic activity under UV light, which is advantageous for environmental applications such as degrading organic pollutants in water69. Although both ZnO and TiO₂ nanoparticles are commonly used for similar purposes, ZnO NPs are often more efficient in certain catalytic reactions due to their higher surface area and reactivity70. Overall, ZnO NPs combine optical, electronic, and chemical properties that make them highly valuable for a wide range of applications, from environmental remediation to advanced biomedical technologies71.

Synthesis of nanoparticles

Fungal synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles

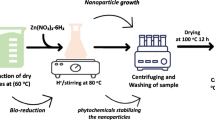

A pure culture of T. harzianum was employed for the fungal production of ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO NPs). Following seven days of broth liquid culture, the fungal mycelia were washed with distilled water and their spores were filtered. Mixed with sterilized double-distilled water, the clean fungal biomass was incubated for a week in an orbital shaking incubator set at 45 °C and 150–200 rpm71. To extract the filtrate, the fungal biomass was sonicated for 30 min; thereafter, it was combined 1:1 with a 5 mM zinc acetate solution. Additionally treated for 24 to 48 h at 150 rpm and 40 °C was this mixture. A color change in the solution verified the development of ZnO nanoparticles. After 15 min at 10,000 rpm, the mixture was centrifuged; the resultant particle was cleaned, dried over night at 40 °C, then heated in a furnace for two hours according to12 (Fig. 2).

Bacterial synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles

B. safensis was used in order for bacterial manufacture of zinc oxide nanoparticles (b-ZnO NPs). The procedure began two days of growing B. safensis in LB broth medium. To get a pure bacterial filtration, the culture was next run through a 0.45 µm Millipore membrane. This filtrate was combined in a 1:1 ratio with a 5 mM zinc acetate solution. The mélange was stirred in a spinning bioreactor that was set to 150 revolutions per minute and 40 degrees Celsius for a period of 24 to 48 h. The quantity of ZnO nanoparticles had decreased, as evidenced by a color transition that occurred during this period. In order to produce the final b-ZnO nanoparticles, the particulate was collected, rinsed, and desiccated overnight at 100 degrees Celsius. Next, it was calcined at 500 degrees Celsius for two hours. The solution that was generated was centrifuged at 8000 revolutions per minute for twenty minutes (Table 1).

Molecular characterization

Under the framework of antifungal uses against chickpea and apricot diseases, the molecular characterization of myco-synthesized and bacteria-synthesized ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) showed numerous important similarities and differences (Fig. 3), thereby clarifying their structural and chemical characteristics. By UV–Visible Spectroscopy characteristic absorption peaks seen in both myco-synthesized and bacteria-synthesized ZnO NPs confirmed their effective production72. While the bacteria-synthesized ZnO NPs had a peak at 340 nm, corresponding with conventional peaks for zinc oxide and validates the effective synthesis of ZnO NPs and relates with their excitonic transitions, the myco-synthesized ZnO NPs produced an absorption peak at 330 nm. Yellowish to white color of the cell-free culture indicates the decrease of zinc acetate by secondary metabolites of cell-free filtrate, thereby producing myco-synthesized ZnO nanoparticles. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy used to determine functional groups, nanoparticles were investigated by FTIR spectroscopy73. Through an FTIR investigation on both kinds of ZnO nanoparticles, scientists found a range of functional groups important for the stability and reduction of the nanoparticles (Table 2). It was shown via myco-synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles that ZnO NPs include a broad spectrum of organic functional groups including alcohols, phenols, carboxylic acids, nitro compounds, aromatics, amines, alkyl halides, and thiols. Conversely, bacteria- synthesized ZnO nanoparticles had peaks matching the NH groups of big aliphatic amines, the C-O groups of alcohols, and a broad spectrum of halogen compounds (C-I, C-Br, and C-Cl). These biomolecules are mostly in charge of capping and reducing ZnO nanoparticles. The mixture was stirred for 24–48 h using an incubator set to a temperature of 40 °C and a shaking speed of 150 rotations per minute. As shown by a change in color, the quantity of ZnO nanoparticles has dropped throughout this time. To generate the last b-ZnO nanoparticles, the pellet was first collected, washed, dried at a temperature of 100 degrees Celsius for a full night, and then calcinated at 500 degrees Celsius for two hours. Twenty minutes of centrifugation at 8000 revolutions per minute will help one to consider the generated solution. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) Structural Analysis used to analyze the crystallinity, size and structure/shape of nanoparticle74. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns obtained on bacteria-synthesized and myco-synthesized ZnO nanoparticles revealed crystalline structure of the nanoparticles. Myco-synthesizing produced ZnO nanoparticles with diffraction peaks at 2θ degrees matching several crystallographic planes of zinc. These were 23, 25, 27, 28, 30, 32, 33, 37, 40, 41, 42, 46, 51, and 56. Synthesized using Debye–Scherer’s equation, the Bacteria-synthesized ZnO nanoparticles showed peaks at 2θ degrees of 31, 34, 36, 47, 56, 62, 67, and 69. These peaks revealed that the 13-nm average particle size of the ZnO nanoparticles had a spherical form. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) Analysis were used. SEM micrographs indicated a spherical form for both kinds of ZnO nanoparticles75. For myco-synthesized ZnO NPs, EDX examination revealed a suitable amount of zinc (30%), therefore verifying their purity. Further confirming the synthesis and elemental composition of the ZnO NPs, bacteria-synthesized ZnO NPs contained greater zinc (70.70%) and oxygen (13.87%), along with trace levels of aluminum and carbon. Both myco-synthesized and bacteria-synthesized ZnO NPs showed good molecular properties suitable for use in antifungals overall. The thorough molecular characterization emphasizes their possible control of plant diseases in chickpea and apricot by stressing the particular functional groups, crystalline structures, and elemental compositions that support their antifungal effectiveness.

Molecular characterization of Myco-synthesized nanoparticles (A) and Bacteria-synthesized nanoparticles (B). It was done for the analysis of molecules like synthesis confirmation, functional groups, size and shape, morphology and elemental composition. Figures are reproduced from doi.org/10.1007/s11274-024-03944-w76 /doi.org/10.3390/jof8070753 12 under CC By 4.0 License.

Characteristic of the In-vitro antifungal assays applied to measure the nanoparticle efficacy

ZnO nanoparticles’ antifungal effectiveness was assessed using the poisoned food approach. This approach combines several ZnO NPs concentrations into potato dextrose agar (PDA) media and tracks fungus growth. PDA media were mixed with various concentrations of ZnO NPs (0.25 mg/ml, 0.50 mg/ml, 0.75 mg/ml, 1.0 mg/ml) after that media was poured into Petri plates and allowed to solidify. Placed at the middle of the Petri plates with the nanoparticle-infused media were 5 mm in diameter fungal discs from a 6-day-old culture of the target fungus (e.g., A. solani or F. oxysporum). The plates were incubated at 24–28 °C (for F. oxysporum) or 28 °C (for A. solani) for 7 days. Control plates containing PDA media without ZnO NPs were also prepared. The mycelial growth was measured, and the inhibition of mycelial growth was calculated using the formula:

where: TT = average mycelial growth in treated plates, CC = average mycelial growth in control plates.

Explanation of the parameters measured

Inhibition zone diameter value gauges the radius of the clear zone around the fungal disc where the ZnO NPs have slowed down fungal development77. It offers a direct numerical and visual estimate of the nanoparticle antifungal activity. After incubation, minimum inhibitory concentration MIC is the lowest concentration of ZnO NPs that stops obvious fungal growth. Finding the potency of the nanoparticles against the fungal infection depends on this crucial value. Minimum fungicidal concentration MFC guarantees no regrowth on a fresh media by having the lowest concentration of ZnO NPs killing the fungal pathogen. MFC offers a quantification of the capacity of the nanoparticles to function as a fungicidal agent instead of only preventing fungal development. These data taken together provide a comprehensive assessment of the antifungal efficacy of the generated ZnO nanoparticles, therefore underlining its prospective utility as a replacement for conventional fungicides in the prevention of fungal diseases.

Antifungal analysis of myco-synthesized ZnO nanoparticles

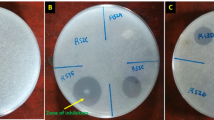

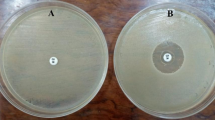

The research on chickpeas concentrated on the common fungal pathogen F. oxysporum (Fig. 4). The T. harzianum filtrate was used in synthesis of the ZnO nanoparticles. At 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 1.0 μg/mL varying concentrations, the antifungal effectiveness was investigated. With the highest mycelial growth decrease (85.6%) seen at a concentration of 0.50 μg/mL ZnO NPs, the in-vitro data revealed varied growth inhibition of F. oxysporum.

Antifungal analysis of bacteria-synthesized ZnO nanoparticles

In the investigation combining A. solani and apricots, filtrate of B. safensis was used to synthesis ZnO nanoparticles (Fig. 5). Testing the antifungal effectiveness at several dosages (0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 1.0 mg/mL) at 0.75 mg/mL of ZnO NPs, the highest mycelial growth reduction—85.2%—was obtained Particularly at higher doses, the findings revealed a significant suppression of fungal development (Table 3).

In-vitro antifungal treatment of bacterial nanoparticles. Figure is reproduced from doi.org/10.1007/s11274-024-03944-w76 under CC By 4.0 License.

Comparative study of two types of nanoparticles against various fungal pathogens of chickpea and apricot: antifungal efficacy

By means of their performance against F. oxysporum and A. solani respectively, the antifungal effectiveness of myco-synthesized and bacteria-synthesized ZnO nanoparticles may be evaluated:

Myco-synthesized ZnO NPs (F. oxysporum in chickpea)

Maximum efficacy of fungal nanoparticles was at the concentration of 0.50 μg/mL that is 85.2% growth inhibition of F. oxysporium pathogen. It is the lesser concentration of nanoparticle that has inhibited the growth of pathogen it means nanoparticles are much effective that can affect even in small quantity of nanoparticles. Comparable to the bacterial nanoparticles and chemical fungicides that these nanoparticles are effective (Fig. 6).

Bacteria-synthesized ZnO NPs (A. solani in apricot)

Maximum efficacy of fungal nanoparticles was at the concentration of 0.750 μg/mL that is 85.1% growth inhibition of A. solani pathogen. It is the second highest concentration of experiment in which nanoparticles showed the good results of growth inhibition of pathogen. More concentrated solutions needed for comparable degrees of inhibition. The nanoparticles can be compared with the chemical fungicides that are non-biodegradable. Notable inhibition is seen at many doses of nanoparticles.

Potential factors influencing the antifungal activity of the nanoparticles

Concentration

ZnO nanoparticles have very concentration-dependent antifungal action 78. Higher concentrations of ZnO NPs clearly produced more suppression of fungal development according both experiments79. Comparatively to myco-synthesis produced ZnO NPs (0.50 μg/mL), the bacteria-synthesized ZnO NPs needed greater concentrations (0.75 mg/mL) to get equivalent inhibitory levels. This implies that the kind of fungal pathogen aimed against and the manufacturing technique may affect the effective concentration.

Size

The antifungal effect of the nanoparticles may be much influenced by their size80. Usually with a greater surface area to volume ratio, smaller nanoparticles improve their contact with fungal cells81. The average size of the myco-synthesized ZnO NPs in the chickpea research was 14 nm, which most certainly helped to explain their great potency at lower doses. While the size distribution of bacteria-synthesized ZnO NPs was not stated, their efficacy at greater concentrations would suggest either a different size distribution or a bigger average size. Due to smaller size of myco-synthesized NPs have high surface to volume ratio that increase their potential regarding reactivity and interaction with pathogen.

Surface modification

The stability, dispersity, and reactivity of nanoparticles may be changed by surface modification and capping agents present82. Both investigations’ FTIR analyses turned up many functional groups that could help to lower and cap the ZnO NPs. Interaction between these functional groups and fungal cell membranes improves antifungal effectiveness83. The particular biomolecules from T. harzianum and B. safensis used in the synthesis procedure most certainly helped to explain the variations in antifungal potency and necessary concentrations. Specifically, in myco-synthesized NPs the reduction and stabilization of Zn ions by the metabolites of Trichoderma play crucial role, metabolites like amino acids, proteins and phenolic compounds. Lipopeptides and secondary metabolites secreted by biocontrol agents such as Bacillus and Trichoderma used in the synthesis of nanoparticles provide synergistic support in inhibiting various plant pathogens84,85,86. This discussion demonstrates the activity of nanoparticles produced by Bacillus and Trichoderma in inhibiting plant pathogens.

Conclusion

The antifungal activity of myco-synthesized and bacteria-synthesized ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) against pathogen of chickpea and apricot was assessed in this work. Strong antifungal capability, non-toxicity, and environmental friendliness let ZnO NPs—synthesized from T. harzianum mycotoxins—effectively prevent Fusarium wilt in chickpea. Furthermore, suited for seed priming and broad agricultural use are these myco-synthesized NPs as they may improve plant physiology and biochemistry. Conversely, B. safensis filtrate-based ZnO nanoparticles (b-ZnO NPs) showed good control of black heart rot disease in apricot, therefore enabling afflicted fruits to retain larger concentrations of soluble sugars, ascorbic acid, and carotenoids. The encouraging findings imply that both forms of ZnO NPs might be efficiently used for disease management in different crops, therefore providing a sustainable method of controlling plant diseases.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bhar, A., Jain, A. & Das, S. Soil pathogen, Fusarium oxysporum induced wilt disease in chickpea: A review on its dynamicity and possible control strategies. Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. 87, 260–274 (2021).

Smolińska, U. & Kowalska, B. Biological control of the soil-borne fungal pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: A review. J. Plant Pathol. 100, 1–12 (2018).

Kumar, A., Bhuj, B. D. & Dhar, S. New approaches for Almonds (Prunus amygdalus Batsch) production in mediterranean climates: A review. J. Agric. Aquac. 5, (2023).

Khan, N. A., Bhat, Z. A. & Bhat, M. A. Diseases of stone fruit crops. Prod. Technol. Stone Fruits 359–395 (2021).

Mahmood, Q., Shaheen, S. & Azeem, M. Nanobiosensors: application in healthcare, environmental monitoring and food safety. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2024(1), 2023157. https://doi.org/10.35495/ajab.2023.157.

Pandit, M. A. et al. Major biological control strategies for plant pathogens. Pathogens 11, 273 (2022).

Gupta, P. K. Herbicides and fungicides. in Reproductive and Developmental Toxicology 665–689 (Elsevier, 2022).

Zehra, A. et al. An overview of nanotechnology in plant disease management, food safety, and sustainable agriculture. Food Secur. Plant Dis. Manag. 193–219 (2021).

Jain, D. et al. Microbial fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles and evaluation of their antimicrobial and photocatalytic properties. Front. Chem. 8, 778 (2020).

Phal P, Soytong K and Poeaim S. A new nanofibre derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control durian rot caused by Phytophthora palmivora. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2024(2): 2023182. DOI: https://doi.org/10.35495/ajab.2023.182

Ahmed, S. F. et al. Green approaches in synthesising nanomaterials for environmental nanobioremediation: Technological advancements, applications, benefits and challenges. Environ. Res. 204, 111967 (2022).

Farhana, et al. ZnO nanoparticle-mediated seed priming induces biochemical and antioxidant changes in chickpea to alleviate Fusarium wilt. J. Fungi 8, 753 (2022).

Pisano, R. & Durlo, A. Feynman’s frameworks on nanotechnology in historiographical debate. in Handbook for the Historiography of Science 441–478 (Springer, 2023).

Srivastava, S., Bhargava, A., Srivastava, S. & Bhargava, A. Green nanotechnology: An overview. Green Nanopart. Futur. Nanobiotechnol. 1–13 (2022).

Moriarty, P. Nanotechnology: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2022).

Bayda, S., Adeel, M., Tuccinardi, T., Cordani, M. & Rizzolio, F. The history of nanoscience and nanotechnology: From chemical–physical applications to nanomedicine. Molecules 25, 112 (2019).

Tovar-Lopez, F. J. Recent progress in micro-and nanotechnology-enabled sensors for biomedical and environmental challenges. Sensors 23, 5406 (2023).

Saleh, T. A. Trends in nanomaterial types, synthesis methods, properties and uses: Toxicity, environmental concerns and economic viability. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 37, 101109 (2024).

Sahu, M. K., Yadav, R. & Tiwari, S. P. Recent advances in nanotechnology. Int. J. Nanomater. Nanotechnol. Nanomed. 9, 15–23 (2023).

Khan, Y. et al. Classification, synthetic, and characterization approaches to nanoparticles, and their applications in various fields of nanotechnology: A review. Catalysts 12, 1386 (2022).

Ahire, S. A. et al. The Augmentation of nanotechnology era: A concise review on fundamental concepts of nanotechnology and applications in material science and technology. Results Chem. 4, 100633 (2022).

Wang, G. Nanotechnology: The new features. arXiv Prepr. http://arxiv.org/abs/1812.04939 (2018).

Gupta, P. K. Introduction and historical background. in Nanotoxicology in Nanobiomedicine 1–22 (Springer, 2023).

Al-Mutairi, N. H., Mehdi, A. H. & Kadhim, B. J. Nanocomposites materials definitions, types and some of their applications: A review. Eur. J. Res. Dev. Sustain. 3, 102–108 (2022).

Mehra, R. M. Electronic and mechanical properties of nanoparticles. in Applications of Nanomaterials for Energy Storage Devices 127–141 (CRC Press, 2022).

Aldeen, T. S., Mohamed, H. E. A. & Maaza, M. ZnO nanoparticles prepared via a green synthesis approach: Physical properties, photocatalytic and antibacterial activity. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 160, 110313 (2022).

Sharma, P., Hasan, M. R., Mehto, N. K., Bishoyi, A. & Narang, J. 92 years of zinc oxide: Has been studied by the scientific community since the 1930s-An overview. Sensors Int. 3, 100182 (2022).

Allayeith, H. K. Zinc-based nanoparticles prepared by a top-down method exhibit extraordinary antibacterial activity against both Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. at (2020).

Cruz, D. M. et al. Green nanotechnology-based zinc oxide (ZnO) nanomaterials for biomedical applications: A review. J. Phys. Mater. 3, 34005 (2020).

Gadewar, M. et al. Unlocking nature’s potential: Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and their multifaceted applications-A concise overview. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 101774 (2023).

Rohani, R., Dzulkharnien, N. S. F., Harun, N. H. & Ilias, I. A. Green approaches, potentials, and applications of zinc oxide nanoparticles in surface coatings and films. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2022, 3077747 (2022).

Abdullah, F. H., Bakar, N. H. H. A. & Bakar, M. A. Current advancements on the fabrication, modification, and industrial application of zinc oxide as photocatalyst in the removal of organic and inorganic contaminants in aquatic systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 424, 127416 (2022).

Raha, S. & Ahmaruzzaman, M. ZnO nanostructured materials and their potential applications: progress, challenges and perspectives. Nanoscale Adv. 4, 1868–1925 (2022).

Anjum, S. et al. Recent advances in zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) for cancer diagnosis, target drug delivery, and treatment. Cancers (Basel) 13, 4570 (2021).

Ali, A., Phull, A.-R. & Zia, M. Elemental zinc to zinc nanoparticles: Is ZnO NPs crucial for life? Synthesis, toxicological, and environmental concerns. Nanotechnol. Rev. 7, 413–441 (2018).

Rasool, M., Rasool, M. H,, Khurshid, M. & Aslam, B. Biogenic synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles: exploring antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities and assessing antimicrobial potential against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2024(3), 2023364. https://doi.org/10.35495/ajab.2023.364.

Gauba, A. et al. The versatility of green synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles in sustainable agriculture: A review on metal-microbe interaction that rewards agriculture. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 125, 102023 (2023).

Ahamad Khan, M. et al. Phytogenically synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) potentially inhibit the bacterial pathogens: In vitro studies. Toxics 11, 452 (2023).

Godoy-Gallardo, M. et al. Antibacterial approaches in tissue engineering using metal ions and nanoparticles: From mechanisms to applications. Bioact. Mater. 6, 4470–4490 (2021).

Maity, D., Gupta, U. & Saha, S. Biosynthesized metal oxide nanoparticles for sustainable agriculture: Next-generation nanotechnology for crop production, protection and management. Nanoscale 14, 13950–13989 (2022).

Kamal, A. et al. Mycosynthesis, characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles, and its assessment in various biological activities. Crystals 13, 171 (2023).

Kaur, H., Rauwel, P. & Rauwel, E. Antimicrobial nanoparticles: Synthesis, mechanism of actions. in Antimicrobial Activity of Nanoparticles 155–202 (Elsevier, 2023).

Mukherjee, A. G., Gopalakrishnan, A. V. & Mukherjee, A. The application of nanomaterials in designing promising diagnostic, preservation, and therapeutic strategies in combating male infertility: A review. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 105356 (2024).

Alshehri, A. A. et al. Microbial Nanoparticles for cancer treatment. Microb. Nanotechnol. Green Synth. Appl. 217–235 (2021).

Faizan, M., Yu, F., Chen, C., Faraz, A. & Hayat, S. Zinc oxide nanoparticles help to enhance plant growth and alleviate abiotic stress: A review. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 22, 362–375 (2021).

Zhao, W. et al. Engineered Zn-based nano-pesticides as an opportunity for treatment of phytopathogens in agriculture. NanoImpact 28, 100420 (2022).

Liu, L., Nian, H. & Lian, T. Plants and rhizospheric environment: Affected by zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs). A review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 185, 91–100 (2022).

Suganya, A., Saravanan, A. & Manivannan, N. Role of zinc nutrition for increasing zinc availability, uptake, yield, and quality of maize (Zea mays L.) grains: An overview. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 51, 2001–2021 (2020).

Saper, R. B. & Rash, R. Zinc: An essential micronutrient. Am. Fam. Phys. 79, 768 (2009).

Ramezani, M., Mohd Ripin, Z., Pasang, T. & Jiang, C.-P. Surface engineering of metals: techniques, characterizations and applications. Metals (Basel) 13, 1299 (2023).

Saeed, M., Marwani, H. M., Shahzad, U., Asiri, A. M. & Rahman, M. M. Recent advances, challenges, and future perspectives of ZnO nanostructure materials towards energy applications. Chem. Rec. 24, e202300106 (2024).

Harish, V. et al. Review on nanoparticles and nanostructured materials: Bioimaging, biosensing, drug delivery, tissue engineering, antimicrobial, and agro-food applications. Nanomaterials 12, 457 (2022).

Cao, H., Qiao, S., Qin, H. & Jandt, K. D. Antibacterial designs for implantable medical devices: Evolutions and challenges. J. Funct. Biomater. 13, 86 (2022).

Baby, R., Hussein, M. Z., Abdullah, A. H. & Zainal, Z. Nanomaterials for the treatment of heavy metal contaminated water. Polymers (Basel) 14, 583 (2022).

Fatima, F., Hashim, A. & Anees, S. Efficacy of nanoparticles as nanofertilizer production: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 1292–1303 (2021).

Kuthi, N. A., Basar, N. & Chandren, S. Nanonutrition-and nanoparticle-based ultraviolet rays protection of skin. in Advances in Nanotechnology-Based Drug Delivery Systems 227–280 (Elsevier, 2022).

Zhang, W., Sani, M. A., Zhang, Z., McClements, D. J. & Jafari, S. M. High performance biopolymeric packaging films containing zinc oxide nanoparticles for fresh food preservation: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 230, 123188 (2023).

Muhammad, F. et al. Ameliorating drought effects in wheat using an exclusive or co-applied rhizobacteria and ZnO nanoparticles. Biology (Basel) 11, 1564 (2022).

Pomerantseva, E., Bonaccorso, F., Feng, X., Cui, Y. & Gogotsi, Y. Energy storage: The future enabled by nanomaterials. Science (80-) 366, eaan8285 (2019).

Yadav, S. et al. Green nanoparticles for advanced corrosion protection: Current perspectives and future prospects. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 21, 100605 (2024).

Fayyadh, A. A. & Alzubaidy, M. H. J. Green-synthesis and characterization of novel ZnO: Ago: TiO2 nanocomposite for antibacterial activity. in AIP Conference Proceedings vol. 2450 (AIP Publishing, 2022).

Dutta, T., Khan, A. A., Baildya, N., Mondal, P. & Ghosh, N. N. Preparation of ZnO/chitosan nanocomposite and its applications to durable antibacterial, UV-blocking, and textile properties. in Biodegradable and Environmental Applications of Bionanocomposites 169–187 (Springer, 2022).

Ntemogiannis, D. et al. ZnO matrices as a platform for tunable localized surface plasmon resonances of silver nanoparticles. Coatings 14, 69 (2024).

Wang, L.-Y. et al. Size and morphology modulation in ZnO nanostructures for nonlinear optical applications: A review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 9975–10014 (2023).

Krishna, M. S. et al. A review on 2D-ZnO nanostructure based biosensors: From materials to devices. Mater. Adv. 4, 320–354 (2023).

Tripathy, N. & Kim, D.-H. Metal oxide modified ZnO nanomaterials for biosensor applications. Nano Converg. 5, 27 (2018).

Verma, R., Pathak, S., Srivastava, A. K., Prawer, S. & Tomljenovic-Hanic, S. ZnO nanomaterials: Green synthesis, toxicity evaluation and new insights in biomedical applications. J. Alloys Compd. 876, 160175 (2021).

Marica, I., Nekvapil, F., Ștefan, M., Farcău, C. & Falamaș, A. Zinc oxide nanostructures for fluorescence and Raman signal enhancement: A review. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 13, 472–490 (2022).

Kareem, M. A. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic application of silver doped zinc oxide nanoparticles. Clean. Mater. 3, 100041 (2022).

Khan, M. et al. The potential exposure and hazards of metal-based nanoparticles on plants and environment, with special emphasis on ZnO NPs, TiO2 NPs, and AgNPs: A review. Environ. Adv. 6, 100128 (2021).

Ahmed, J. et al. Biocontrol of fruit rot of Litchi chinensis Using zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized in Azadirachta indica. Micromachines 13, (2022).

Rajivgandhi, G. et al. Biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) using actinomycetes enhance the anti-bacterial efficacy against K. Pneumoniae. J. King Saud Univ. 34, 101731 (2022).

Eid, M. M. Characterization of nanoparticles by FTIR and FTIR-microscopy. in Handbook of consumer nanoproducts 1–30 (Springer, 2022).

Bekele, B., Jule, L. T. & Saka, A. The effects of annealing temperature on size, shape, structure and optical properties of synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles by sol-gel methods. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 16, 471–478 (2021).

Sharma, S., Kumar, K., Thakur, N., Chauhan, S. & Chauhan, M. S. The effect of shape and size of ZnO nanoparticles on their antimicrobial and photocatalytic activities: A green approach. Bull. Mater. Sci. 43, 1–10 (2020).

Farhana, et al. Bacillus safensis filtrate-based ZnO nanoparticles control black heart rot disease of apricot fruits by maintaining its soluble sugars and carotenoids. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 40, 125 (2024).

Roychoudhury, A., Sarkar, R. & Sarkar, R. Unlocking the potential of fungal extracts as inhibitors of biofilm formation and improving human health. J. Stress Physiol. Biochem. 20, 195–217 (2024).

Pariona, N. et al. Shape-dependent antifungal activity of ZnO particles against phytopathogenic fungi. Appl. Nanosci. 10, 435–443 (2020).

Abdelaziz, A. M. et al. Potential of biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles to control Fusarium wilt disease in eggplant (Solanum melongena) and promote plant growth. BioMetals 35, 601–616 (2022).

Matras, E., Gorczyca, A., Przemieniecki, S. W. & Oćwieja, M. Surface properties-dependent antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 12, 18046 (2022).

da Silva, B. L., Caetano, B. L., Chiari-Andréo, B. G., Pietro, R. C. L. R. & Chiavacci, L. A. Increased antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticles: Influence of size and surface modification. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 177, 440–447 (2019).

Javed, R. et al. Role of capping agents in the application of nanoparticles in biomedicine and environmental remediation: recent trends and future prospects. J. Nanobiotechnology 18, 1–15 (2020).

Djearamane, S. et al. Antifungal properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles on Candida albicans. Coatings 12, 1864 (2022).

Tomah, A. A., Alamer, I. S. A., Li, B. & Zhang, J.-Z. Mycosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using screened Trichoderma isolates and their antifungal activity against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Nanomaterials 10, 1955 (2020).

Abd Alamer, I. S., Tomah, A. A., Ahmed, T., Li, B. & Zhang, J. Biosynthesis of silver chloride nanoparticles by rhizospheric bacteria and their antibacterial activity against phytopathogenic bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum. Molecules 27, 224 (2021).

Tomah, A. A. et al. The potential of Trichoderma-mediated nanotechnology application in sustainable development scopes. Nanomaterials 13, 2475 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A. participated in the writing, reviewing, and editing of the original manuscript, F., G.A.M, A.R.K, B.Z, A.W, R.I, and M.R. Provided funding and contributed to the reviewing and editing of the manuscript, R.I, and M.R, helped in the collection of literatures review and participated in writing the original manuscript, A.R.K, B.Z, A.W, R.I, and M.R, revised the manuscript and eliminated grammatical mistakes. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, J., Farhana, Manzoor, G.A. et al. In-vitro antifungal potential of myco versus bacteria synthesized ZnO NPs against chickpea and apricot pathogen. Sci Rep 15, 148 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84438-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84438-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

ZnO nanoparticles in biomedical and agricultural applications: a review on double-edged sword of genotoxicity and therapeutic potential

Nanotechnology for Environmental Engineering (2026)