Abstract

In this study, we aimed to enhance the photocatalytic performance of molybdenum oxide (MoO3) thin films by doping with silver (Ag) via a spray pyrolysis technique. The primary objective for silver incorporation was intended to introduce additional energy levels into the band structure of MoO3, improving its efficiency. Structural, optical, and photocatalytic properties were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and optical spectroscopy. XRD results confirmed an orthorhombic phase with a (040) preferential orientation for all samples. Optimal crystallinity was observed with 2% Ag doping, yielding an 84 nm crystallite size, while higher doping levels reduced crystallite size. Band gap energy narrowed from 3.07 eV (undoped) to 2.94 eV (2% Ag-doped), indicating electronic structure changes. Impedance spectroscopy revealed superior electrical properties at 4% Ag doping, enhancing charge transport. Photocatalytic performance, assessed via dye degradation, showed significant improvement with silver doping, the degradation rate peaking at 4% Ag. These results demonstrate that silver doping optimizes structural and electronic properties of MoO3 thin films, leading to enhanced photocatalytic activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transition metal oxide semiconductor has garnered significant attention in recent years due to their technological applications, particularly in oxide photocatalyst and solar cells1,2,3,4,5. These solar cells represent a promising, low-cost photovoltaic technology thanks to their high-power conversion efficiency. Additionally, metal oxides have found extensive use in charge storage devices6,7, memory devices8, solid oxide fuel cells9 and supercapacitors10.

Molybdenum trioxide (MoO3) is a notable metal oxide with significant potential. As an n-type semiconductor with a wide band gap energy of around 3 eV11, MoO3 is a valuable component in photovoltaic cells. Its unique optical properties have led to extensive research, making it one of the most utilized materials in optical devices12 and smart windows13. Furthermore, MoO3 has diverse applications in chemical engineering, medicine, and agriculture14,15. Recently, due to its remarkable structural and electrical characteristics, MoO3 has been incorporated into transistors16, catalysts17,18, electrochemical capacitors19, gas sensors20, and the production of ceramics and glass21.

MoO3 exhibits three crystallographic structures: one stable phase, α-MoO3, and two metastable phases, β-MoO3 and h-MoO322. The electrical properties of MoO3 and its derivatives are significantly influenced by the synthesis techniques and growth conditions22. Since 2011, MoO3 has been prepared using chemical techniques and deposited on substrates through various chemical and physical methods, including thermal evaporation23, spin coating24, chemical vapor deposition25, sol-gel processing26, hydrothermal methods27, and solid-state reactions28. However, most of these synthesis methods require high temperatures or pressures, extended processing times, and the use of closed systems with complex equipment.

MoO3 has a bandgap that efficiently absorbs visible light, making it highly suitable for photocatalytic applications29. Unlike copper oxide (Cu2O), which possesses a direct bandgap advantageous for visible light absorption but necessitates higher photon energies for electron excitation30,31. Additionally, MoO3 offers superior chemical stability and durability32.

Doping is a well-known method for modifying the properties of thin films semiconductor. Specifically, strategic doping can improve the physical characteristics of MoO3 thin films. Noble metals like gold (Au), silver (Ag), and platinum (Pt) are prime candidates among transition metals because they (i) capture photogenerated electrons, increasing the lifespan and mobility of these carriers, and (ii) display a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect when exposed to light33,34. Among these valuable metals, silver (Ag) is especially preferred in this study for its outstanding stability, photocatalytic properties, antimicrobial properties, photovoltaic features, and lower cost.

Doping of molybdenum trioxide with other metals has been explored to reduce its band gap energy and enhance various physical properties, depending on the nature and concentration of the dopants35,36,37,38,39,40. One notable application of these materials is their photocatalytic effect. Similar studies have been conducted on this material, where researchers examined the impact of doping with metals such as Dy41, Eu42, Ce43, Sn44 Au45 and Ag7,15,44,46 on their photocatalytic efficiency.

This doped MoO3 has shown enhanced photocatalytic activity, surpassing that of undoped materials. This improvement is attributed to the creation of an intermediate state associated with a reduced band gap, resulting in significantly increased degradation efficiency due to doping47.

The spray technique was chosen for this study48,49. Spray Pyrolysis, which originated in the 1980s, has evolved into a crucial technology for synthesizing thin film materials from precursor solutions50. Known for its adaptability and scalability in depositing uniform composite materials and diverse nanostructured functional materials, Spray Pyrolysis has been extensively applied over the past four decades in semiconductor thin films50. Its straightforward operation and high efficiency continue to drive research aimed at depositing thin films of noble metals, mineral oxides, metal oxides, chalcogenides, and superconducting materials using this method50. Notably, Spray Pyrolysis offers distinct advantages: it allows easy doping by adding dopants to the aqueous spray precursor solution, eliminates the need for expensive targets and high-quality substrates required by vacuum deposition methods, provides precise control over deposition rate and film thickness across a wide spray range, and operates at moderate temperatures (~ 200–500 °C) without restrictions on substrate dimensions or surface profiles50.

In this study, we detail the synthesis process of both pure MoO3 and Ag-doped MoO3 with varying Ag concentrations. We investigate the impact of these dopants on the structural and optical properties of MoO3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) was employed to examine the structure and phases present in the samples. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was utilized to study the sample morphology, while energy-dispersive X-ray analyses (EDAX) was used to analyze the chemical composition. UV-Vis Reflectance Spectroscopy (RS) measurements were conducted to analyze and measure the band gap. Additionally, the electrical properties were examined using Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS). The photocatalytic activity of nanosized MoO3, synthesized using spray pyrolysis, is evaluated for the degradation of model organic dyes like methylene blue (MB) and methyl orange (MO) in an aqueous medium. The degradation efficiency of MoO3 with varying levels of Ag doping is compared, and the results are thoroughly analyzed and discussed.

To our knowledge, there is currently no existing literature investigating the simplest spray deposited MoO3 for photocatalytic applications. This unique approach provides valuable insights into the potential of this stable and non-toxic material for achieving efficient and environmentally friendly photocatalysis.

Experimental details

Synthesis of Ag doped MoO3 thin films

Thin films were deposited on glass substrates by spray pyrolysis at 460 °C using the method described by Kamoun et al.51. The spray solution consists of 0.01 M aqueous solution of ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate [(NH4)6Mo7O244H2O] and the silver source is AgCl. The Ag/Mo molar ratios were 0%, 2%, 4% and 6%. Compressed air was used as a carrier gas and was blown through a nozzle with a diameter of 0.5 mm at a pressure of 0.35 bar. The flow rate of the precursor mixture during deposition was 6.67·10−5 L/s. After deposition, the film was allowed to cool.

Characterization of Ag doped MoO3 thin films

Crystal structure of the film was analyzed using a Philips PW 1729 X-ray machine Diffractometer with monochromatic Cu-Ka radiation (λ = 0.15405 nm). Optical reflectance R(λ) and transmittance T(λ) were measured in the wavelength range from 200 to 2000 nm using a Perkin-Elmer spectrophotometer. The electrical properties of undoped and Ag doped MoO3-Ag films were studied by electrical impedance spectroscopy at room temperature using an Agilent E4980A impedance analyzer in the frequency range [20 Hz–2 MHz].

Measurement of the photocatalytic decomposition of methylene blue (MB) was done using sunlight. Firstly, we place MoO3:Ag thin film sample with the size of 1 cm × 3 cm in 25 mL aqueous solution containing MB at a concentration of 10−5 mol/L, in dark, for about 30 min in order to establish the adsorption-desorption equilibrium, where the molecules of MB may be adsorbed on to the surface of sample. The photocatalytic activity of MoO3:Ag was evaluated against methylene blue dyes using a solar simulator with an intensity of 1000 W/m2, simulating natural sunlight AM (1.5) conditions.

Results and discussion

X-ray diffraction analysis

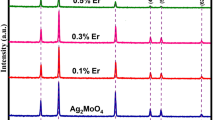

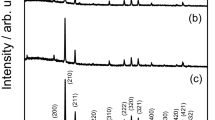

The XRD patterns of the undoped MoO3 films and Ag-doped MoO3 films with different molar concentrations are shown in Fig. 1. The XRD pattern shows that the MoO3 films are polycrystalline in nature, and the diffraction peaks obtained are relatively large.

MoO3 crystallizes in an orthorhombic structure, preferentially oriented on the (040) plane (standard JCPDS No. 05-050852). The peaks are indexed to (0 2 0), (0 4 0) and (0 2 1), which is consistent with the orthorhombic system of the crystal phase α-MoO3. The strongest diffraction peak corresponds to the [0 4 0] direction.

The k values of 2 and 4 in the (0 k 0) plane indicate that the film has good crystallinity and the MoO3 film was successfully deposited. Ag-doped MoO3 films exhibit diffraction peaks similar to those of crystalline MoO3. There are no other characteristic peaks corresponding to the Ag phase detected in the doped film, suggesting that Ag is not present as elemental phase but substitutes for Mo atoms in the crystal structure of MoO3. Song et al.53 suggested that Ag atoms doped uniformly in the MoO3 lattice without affecting the crystal structure of MoO3.

However, the peak position and intensity changed noticeably with Ag concentrations. Diffraction intensity reduction in MoO3:Ag (2%) is a well-known effect and usually occurs due to lattice strain caused by impurity atoms54. The peak intensity increases for MoO3:Ag (6%). The Ag+ ionic radius is 115 pm, which is larger than that of Mo6+ ions of 59 pm53,55. Furthermore, at high Ag/Mo doping ratios, a significant shift in the peak position towards a larger angle was observed compared to the undoped MoO3. The shift to higher angles is attributed to the reduction if the interlayer spacing by partial substitution of Mo atoms in MoO3 with Ag dopant atoms, confirming the incorporation of Ag ions into the MoO3 structure. Similar observations were reported by Munawar et al.56.

The interplanar spacing dhkl values were calculated based on the principal phase by using Bragg equation:

where \(n\) is the diffraction order (usually \(n = 1\)) and \(\lambda\)is the X-ray wavelength. The following relationship was used to determine the effect of different doping concentrations on the lattice parameters of MoO3:

where a, b and c are the lattice constants, \(\left(hkl\right)\)Miller index, and “\(d\)” is the distance between crystal planes. The estimated lattice constants are 3.93 Å, 13.66 Å, and 3.68 Å for a, b, and c, respectively, which agree well with standard JCPDS data for MoO3.

The Ag-doped MoO3 film has a preferential growth direction. Therefore, the lattice parameters such as grain size (D), microstrain (ε) and dislocation density (δ) are calculated using the Scherrer relationship as follows:

where β is the FWHM, λ is the wavelength of Cu-Kα1 radiation (1.5406 Å) and θ is the Bragg diffraction angle. The calculated crystallite parameters are presented in Table 1.

By doping MoO3 with Ag, the average crystal size (D) gradually decreases. However, at a higher Ag doping level of 6%, the crystallite size decreases due to the higher dislocation density and microstrain of 2.99·1014 lines/m2 and 5.99·10−4, respectively.

Optical properties

The optical properties of the Ag-doped MoO3 thin films were examined using UV spectroscopy. The transmission and reflection measurements are shown in Fig. 2a and b, respectively. The average optical transmission is in the range of [30–60]% in the visible domain, while the reflectance in the visible range is in the range of [55–70]%. The Ag doping of MoO3 changes significantly in the transmission and reflection spectra. For the undoped MoO3 thin film, the highest transmittance, and the lowest reflectivity are obtained. The fundamental absorption edge of a semiconductor is the charge transfer barrier between the highest nearly full band and the lowest nearly empty band.

Regarding direct interband transitions, the intrinsic absorption edge of the film can be examined. The absorption coefficient (α) is determined using the relationship:

where k is the extinction coefficient and λ is the wavelength. A plot of (αhν)n versus photon energy (hν), called a Tauc plot, is expected to show linear behavior in the higher energy region, corresponding to strong absorption around the absorption edge.

The optical absorption edge was analyzed by the following equation57:

where, B is a constant. Eg is the band-gap energy of the corresponding material, n is a number that has the values of 1/2 or 2 for direct transition and indirect ones, respectively.

In Fig. 3, we report the variation of (αhν)2 as a function of n. Extrapolation of the linear component at (αhν)2 = 0 represents the band gap of MoO3:Ag material.

According to this figure, the bandgap value of pure MoO3 thin film was determined to be 3.07 eV, which decreased to approximately 2.94 eV for MoO3(Ag:2%). This result demonstrates that the introduction of Ag ions into the lattice creates additional energy levels in the band structure, resulting in a decrease in the bandgap value. This behavior was similar to that observed by other researchers44,57.

This is evident from the red shift of the shoulder in the transmission spectrum. This dopant is suitable for narrowing the band gap value by exploiting its valence state and sub-band states near the conduction band edge/maximum. However, this type of phenomenon can also be attributed to the creation of vacancies, defects, changes in crystallite size, and compositional changes of the dopants in the host lattice.

To study defects and their effects on optical transitions, the Urbach tail/energy was estimated. The coefficient of absorption follows the law presented in Eq. (8), where α0 is a constant and EU is the Urbach energy, which characterizes the slope of the exponential limit:

The logarithmic absorption coefficient curves versus the photon energy (eV) are plotted (see Fig. 4).

The slope is plotted in the linear region/absorption edge of the spectrum, and the reciprocal slope represents the Urbach energy (Eu) of the system.

The observed trend indicates that the estimated Eu varies with the dopant levels up to MoO3:Ag 6%. The bare MoO3 thin-film structure exhibits an Eu of 3.69 meV, which increases to 161.9 meV upon incorporating Ag 6% into the host lattice. After that, Eu decreases with increasing Ag doping level, Eu equals to 131.9meV and 105.7 meV for Ag content equal to 2 and 4%, respectively.

All experiments were conducted at room temperature, where the thermal assistance to Eu can be deemed negligible. Consequently, the substitution of Ag at Mo-sites induces disorder in the electronic transitions and structural defects within the system. The random distribution of inserted Ag ions in the MoO3 lattice results in distinctions between the doped ions and the host Mo ions, causing disorder in the system. These changes may introduce sub-bands or new energy levels near the valence/conduction band, contributing to disorder or high Eu related to the doping concentrations.

Electrical impedance spectroscopy study (EIS)

To understand how the presence of Ag doping affects the electronic properties of MoO3 films, electrical impedance measurements were performed at room temperature by applying an alternating current (AC) of 1 V and varying the frequency between 20 Hz and 2 Hz in dark, using an Agilent E4980 impedance analyzer. It is well known that EIS is a powerful technique that can study device interface properties58. In this study, we analyze the electrical properties of undoped and doped MoO3 films with different percentage of Ag concentrations (0%, 2%, 4%, and 6%). Impedance data can be visualized in two ways: by plotting the imaginary part (-Z”) versus the real part (Z’) (called a Nyquist plot) or by plotting amplitude (|Z|) and/or phase angle (ϕ) relative to log f (called Bode plot)59.

Figure 5.a shows the Nyquist plot (-Z” vs. Z’) for all the films in the dark. As can be seen from this figure, the impedance spectrum of each film has a semicircular arc. Each film has a central semicircle, which is shifted toward the real axis, confirming the Debye relaxation process60,61. It can be seen from Fig. 5.a that the resistance of the MoO3 film is affected by silver doping concentration.

In particular, no silver doping produces a resistive layer, whereas for 4% Ag-doped MoO3 (Fig. 5b), a smallest semicircle with a diameter of approximately 4.7 × 107 Ω is observed. This suggests that Ag improves charge transport between core particles through its electrical conductivity, thus reducing the overall impedance of the film. In fact, the results show that the MoO3 film doped with 4% Ag has good electrical properties.

In addition, the Nyquist plot derived from the experimental impedance spectrum data collected for the Ag-doped MoO3 films under different external bias voltages is shown in Fig. 5b. For all films, the impedance varied in the low-frequency region, indicating modulation of the grain boundaries by the external field. A similar trend was also observed for TiO2-G nanocomposite films62.

To analyze the respective contributions of different components of the material (grains, grain boundaries and electrodes), an equivalent circuit model is required63.For this purpose, the impedance curve is adjusted to an equivalent circuit using Zview software63. The equivalent circuit consists of a series resistor (Rs) and a constant phase element (CPE) in parallel with the resistor (Rp), as shown in the inset of Fig. 5.a. It was found that grains contribute at high frequencies, grain boundaries contribute at medium frequencies, and electrodes contribute at low frequencies64. Table 2 shows the equivalent circuit parameters of the Ag- MoO3 thin films determined by fitting the impedance data. Notably, the smallest resistance was observed for 4% Ag-doped MoO3. Similar behavior was observed by M. Layegh et al.65, for Co- MoO3 thin film.

Figure 6 shows the magnitude of the impedance (|Z|) plotted against a semi-logarithmic frequency scale (log f). In the low frequency range (102 Hz to 103 Hz) the impedance represents the total resistance of the film65. Subsequently, the impedance amplitude decreases and reaches a minimum at high frequency (106 Hz), indicating an increase in film conductivity66. Based on these results, we can conclude that adding silver can improve charge transport by changing the grain boundaries of MoO3 films. This makes Ag-MoO3 nanocomposite a promising candidate for optoelectronic applications.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

SEM analysis was conducted to study the morphology of undoped and doped MoO3:Ag 4% samples. Figure 7a,b presents the SEM images of undoped and 4% silver-doped MoO3, synthesized via spray pyrolysis. These images reveal features such as spherical particles, dark granular zones, fissures and crevices, and bright, shining regions, contributing to a diverse and complex surface. The 4% Ag-doped MoO3 exhibits a rougher, more uneven surface with pillar-like structures compared to the undoped sample, which enhances photocatalytic efficiency by increasing the specific surface area, reducing density, and improving permeability. This structural evolution highlights the potential for optimizing functionalities and uncovering novel physicochemical properties through silver doping.

Figure 8a,b show SEM cross-sectional images of the undoped and 4% Ag-doped samples, respectively. The thickness of the MoO3 thin films increased from approximately 6 μm for the undoped sample to 9 μm after doping with 4% silver.

Figure 9 presents the EDX image of both undoped and Ag 4% doped MoO3. The EDX spectra confirms the presence of Mo and O with an approximate atomic O-to-Mo ratio of 3.75, indicating the formation of MoO3. This ratio remains unchanged despite the increase of Ag doping, aligning with the findings of Khalid et al.67 and corroborated with XRD analysis.

Photocatalytic study

We used the photocatalytic decomposition of methylene blue to test and compare the photocatalytic performance of undoped and Ag-doped MoO3. Before the photoreaction, dye adsorption with catalysts was performed for 30 min in dark conditions to achieve adsorption-desorption equilibrium.

Absorption spectrum of MB solution, without and with MoO3:Ag samples, are analyzed at different times. The UV-VIS absorption spectra of MB solution with MoO3:Ag thin films are shown in Fig. 10. There are two absorption peaks corresponding to methylene blue (MB) at 609 and 660 nm51.

Figure 10 shows that for both MoO3 and Ag-doped MoO3 the absorption decreases by increasing the irradiation time from 0 to 60 min. For MoO3:Ag, the peaks intensity decrease at Ag content from 2 to 4% and then increases for 6% Ag. The best MB degradation is obtained for MoO3:Ag 4% after 60 min of UV-VIS irradiation.

After 1 h of irradiation, approximately 98% of the MB amount was degraded by MoO3:Ag 4% (Fig. 10), while 70% was degraded in the presence of undoped MoO3 film.

To verify the reusability of the photocatalyst, MB degradation experiments were conducted for four cycles using MoO3:Ag 4% under diffused sunlight. As illustrated in Fig. 11, all four cycles showed degradation ranging from 96.7 to 98.5% during 60 min of irradiation, confirming that the MoO3:Ag 4% is quite stable and reusable.

Photocatalytic activity

The photocatalytic activity was assessed through the degradation of methylene blue (MB) under sunlight irradiation. Figure 12 shows the photocatalytic degradation of MB with different thin films over time. The concentration of MB decreases significantly with Ag doping. The MoO3:Ag 4% showing the highest degradation rate. The degradation rate constants (k) were calculated using the first-order reaction model4 :

Where C0, Ct and k are the MB concentration at t = 0, at t ≠ 0 and the degradation rate content respectively. The degradation rate constants are reported in Table 3.

Discussion

The superior photocatalytic performance of MoO:Ag 4% is attributed to its improved conductivity (confirmed through IES measurements), surface alterations resulting from Ag doping, and adjusted bandgap (verified via Tauc plot).

The adjusted bandgap enhances the excitation of valence electrons. Furthermore, Ag doping serves as a blocking agent, potentially reducing the recombination of electron-hole pairs to enhance the catalytic activity of the photocatalyst68,69.

The presence of Ag in the photocatalyst suppressed the aggregation of MoO3, thereby improving charge transport towards the surface. The combined benefits of increased surface area, excellent light absorption properties, and enhanced electronic conductivity in the MoO3 sample synergistically enabled the degradation of nearly 98% of MB dye within just 1 h of solar irradiation. When exposed to light, the catalyst generates electron-hole pairs. The photoexcited electrons in the conduction band of MoO3 can react with water, reducing O2 to O2–. Concurrently, the photoinduced holes in the valence band of MoO3 can react with water to produce a substantial amount of ·OH radicals. The combination of ultrasound irradiation and diffused sunlight further boosts the production of ·OH radicals. These ·OH radicals are primarily responsible for the observed effective degradation of MB dye70,71,72.

Khalid et al.67 found that cobalt doping of MoO3 achieved 82.5% degradation of MB. On the other hand, Shanmugam Mahalingam et al. found that the G-αMoO3 catalyst achieved the highest degradation efficiencies of 97% and 96%73.

Furthermore, from the absorbance spectra of the MB dye solution during the photocatalytic reaction of MoO3 4% (Fig. 10), it is evident that there is no shift observed in the maximum absorbance wavelength peaks of the dye at 663 nm and 615 nm in the visible light region. These absorbance bands disappear after the photocatalysis reaction. This disappearance indicates that the heterocyclic/benzene rings in the MB dye molecule have completely decomposed, resulting in the complete mineralization of MB.

It’s noteworthy to mention that discussing the SPR effect of small metal nanoparticles, particularly those 10 nm or smaller, presents challenges. Specifically, the silver particle sizes in the samples studied here were extremely small, approximately 0.5 nm, making it difficult to assess product selectivity based on exposed growth facets74.

The difference between photoactivities of these samples is possibly due to their different microstructures, as shown from AFM results. Similar behavior was observed by Navgire et al.75.

The photodegradation mechanism of silver doped MoO3 involves several key steps, including photon absorption, charge carrier separation, formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and degradation of organic pollutants. When exposed to light, the MoO3:Ag photocatalyst absorbs photons, promoting electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, creating electron-hole pairs. Silver acts as an electron trap, reducing the recombination rate of electrons and holes, increasing the availability of charge carriers for photocatalytic reactions.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive and can attack organic pollutants, breaking down complex molecules into smaller, less harmful compounds, eventually leading to complete mineralization into CO₂ and H₂O. Silver nanoparticles aid in charge separation and have plasmonic properties that enhance light absorption, increasing the generation of electron-hole pairs and boosting photocatalytic efficiency. In summary, the photo degradation mechanism of silver doped MoO3 involves the absorption of light, generation and separation of electron-hole pairs, formation of reactive oxygen species, and degradation of organic pollutants76.

Table 3 clearly demonstrates that both the degradation rates are influenced by the film thickness as reveled by SEM. As anticipated, the data shows that degradation rates rise with increasing film thickness. The same observation was found by Yu et al.77.

Several studies have reported the effects of doping MoO3 with transition metals such as Fe, Co, Zn and Ag, rare earth elements like Eu, as well as with non-metals like C. This doping strategy aims to modify the physical properties of MoO3 and enhance catalysis, sensing, and electronic properties. The results are summarized in Table 4.

Our study demonstrates that Ag doping uniquely increases both the electrical conductivity and optical properties of MoO3, which can be particularly beneficial for applications in optoelectronic devices. However, Ag doping may be limited by higher costs and lower availability compared to other dopants such as Fe or Co. Therefore, while Ag doping offers distinct advantages, it is crucial to consider the specific application requirements to select the most appropriate dopant. Finally, further studies are in progress to test these films in optoelectronic applications.

Conclusion

The spray synthesis of silver-doped molybdenum oxide (MoO3:Ag) was successfully demonstrated for the first time. Remarkable performances were obtained, especially in the field of photocatalysis under sunlight within 60 min. This innovative approach highlights the potential of MoO3:Ag as a highly effective photocatalytic material for solar-driven applications.

The simplicity of the spray method used to fabricate MoO3 thin films is particularly notable, offering a practical route to creating materials with significant specific surface areas. These properties, combined with the potential for doping with various transition elements, make MoO3 thin films highly versatile for applications in a wide range of sensitive devices including solar cells, gas sensors, and biosensors.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Guo, T., Sun, Y., Song, Y. & Ma, S. Effect of MoO3/WO3 modulation on high-temperature wettability and crystallization behavior of glass and its application in solar cell. Ceram. Int. 50(7, Part B), 12566–12579 (2024).

Chen, F. et al. Solution-deposited MoO3 interface layer for high-performance bifacial kesterite thin film solar cell. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 7(9), 4050–4056 (2024).

Munawar, T. et al. Synthesis of novel heterostructured ZnO-CdO-CuO nanocomposite: characterization and enhanced sunlight driven photocatalytic activity. Mater. Chem. Phys. 249, 122983 (2020).

Munawar, T. et al. Novel tri-phase heterostructured ZnO–Yb2O3–Pr2O3 nanocomposite; structural, optical, photocatalytic and antibacterial studies. Ceram. Int. 46(8, Part A), 11101–11114 (2020).

Nadeem, M. S. et al. Effect of Co/Nd co-doping on the structural, optical, and morphological properties of ZnO nanorods grown on silicon substrate Si (100) by hydrothermal method. J. Lumin. 269, 120484 (2024).

Jia, Y. & Ma, Y. Advances in MoO3-based supercapacitors for electrochemical energy storage. J. Energy Storage. 85, 111103 (2024).

Sen, S. K. et al. Silver incorporated α-MoO3 nanoplates to nanorods: exploring the effects of doping on structural, morphological and optical properties. Mater. Today Commun. 27, 102404 (2021).

Yu, H. et al. Nonvolatile ternary memory devices based on MoO3 nanoparticles embedded in conjugated copolymer with hierarchy charge traps. J. Phys. Chem. C 128(16), 6767–6779 (2024).

Holz, L. I. V. et al. Strontium iron molybdenum oxide as electrocatalyst for nitrous oxide reduction in solid oxide fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 54, 25–36 (2024).

Zhu, Y., Tan, Y. & Li, H. MoO3 nanoplates preparation via self-sacrifice C3N4 for supercapacitors in an acid electrolyte. J. Energy Storage 60, 106657 (2023).

Song, Y., Zhao, Y., Huang, Z. & Zhao, J. Aqueous synthesis of molybdenum trioxide (h-MoO3, α-MoO3·H2O and h-/α-MoO3 composites) and their photochromic properties study. J. Alloys Compd. 693, 1290–1296 (2017).

Dwivedi, C., Mohammad, T. & Dutta, V. Creation of au nanoparticles decorated MoO3 nanorods using CoSP and the application as hole transport layer (HTL) in plasmonic-enhanced organic photovoltaic devices. Sol. Energy 176, 22–29 (2018).

He, T. & Yao, J. Photochromism in composite and hybrid materials based on transition-metal oxides and polyoxometalates. Prog. Mater. Sci. 51(6), 810–879 (2006).

Kumar, N., George, B. P. A., Abrahamse, H., Parashar, V. & Ngila, J. C. Sustainable one-step synthesis of hierarchical microspheres of PEGylated MoS2 nanosheets and MoO3 nanorods: their cytotoxicity towards lung and breast cancer cells. Appl. Surf. Sci. 396, 8–18 (2017).

Raj, A. N. P. et al. Influence of Ag doped MoO3 nanoparticles in the seedling growth and inhibitory action against microbial organisms. J. Cluster Sci. 33(6), 2429–2441 (2022).

Holler, B. A., Crowley, K., Berger, M-H. & Gao, X. P. A. 2D semiconductor transistors with Van Der Waals oxide MoO3 as integrated high-κ gate dielectric. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6(10), 2000635 (2020).

Gomez, L. A., Bavlnka, C. Q., Zhang, T. E., Resasco, D. E. & Crossley, S. P. Revealing the mechanistic details for the selective deoxygenation of carboxylic acids over dynamic MoO3 catalysts. ACS Catal. 13(13), 8455–8466 (2023).

Zeng, Q. et al. Embedding Co in Perovskite MoO3 for superior catalytic oxidation of refractory organic pollutants with peroxymonosulfate. Chemosphere 314, 137726 (2023).

Rahman, A., Sarmah, D. & Das, S. K. A study on Al3+ ion capacitor with MoO3 nanorod and aqueous gel electrolyte. Ionics 29(10), 4253–4261 (2023).

da Silva Júnior, M. G. et al. A brief review of MoO3 and MoO3-based materials and recent technological applications in gas sensors, lithium-ion batteries, adsorption, and photocatalysis. Materials. 16(24), 7657 (2023).

Sukenaga, S. et al. Incorporation limit of MoO3 in sodium borosilicate glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 106(1), 293–305 (2023).

Al-Otaibi, A. L. et al. Structural, optical and photocatalytic studies of Zn doped MoO3 nanobelts. Chem. Phys. 525, 110410 (2019).

Sali, D. P. et al. Role of thermal heat-treatment to achieve a highly polycrystalline and compact α-MoO3 thin films. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 35(1), 53 (2024).

Islam, M. A. et al. Spin-coated high mobility MoO3 thin film for designing highly efficient lead-free perovskite solar cells. Ceram. Int. 50(13, Part B), 23847–23854 (2024).

Dey, S. et al. Probing defect induced room temperature ferromagnetism in chemical vapor deposition grown MoO3 flakes: a correlation with electronic structure and first principle-based calculations. J. Alloys Compd. 980, 173650 (2024).

Mutlu, A. & Tozlu, C. Electrical characterization of Ag/MoO3 – x/p-Si Schottky diodes based on MoO3 – x synthesized via sol–gel method: an investigation on frequency and voltage dependence. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 35(11), 805 (2024).

Aliannezhadi, M., Mirsanai, S. Z., Jamali, M. & Shariatmadar Tehrani, F. Optical and structural properties of bare MoO3 nanobelt, ZnO nanoflakes, and MoO3/ ZnO nanocomposites: the effect of hydrothermal reaction times and molar ratios. Opt. Mater. 147, 114619 (2024).

Roy, D. & Ghosh, M. Cyclic voltammetry–based ethylene sensing in solid-state electrochemistry with an electroactive biopolymer/MoO3 composite membrane. J. Solid State Electrochem. 28(1), 283–295 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Visible-light-induced blue MoO3–C3N4 composite with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Mater. Res. Bull. 70, 500–505 (2015).

Rabbani, A. W. et al. Visible-light-driven photocatalytic properties of copper(I) oxide (Cu2O) and its graphene-based nanocomposites. Baghdad Sci. J. 20(3 Suppl.), 1064–1064 (2023).

Munawar, T. et al. Sunlight-induced photocatalytic degradation of various dyes and bacterial inactivation using CuO–MgO–ZnO nanocomposite. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28(31), 42243–42260 (2021).

Tutel, Y. et al. Cobalt-doped MoO3 thin films and dual-band electrochromic devices with excellent cyclic stability. Appl. Mater. Today. 35, 101924 (2023).

Hou, W. & Cronin, S. B. A review of surface plasmon resonance-enhanced photocatalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23(13), 1612–1619 (2013).

Wang, X. & Lim, T-T. Highly efficient and stable Ag–AgBr/TiO2 composites for destruction of Escherichia coli under visible light irradiation. Water Res. 47(12), 4148–4158 (2013).

Guo, W., Chen, K. & Wang, J. Hydrothermal synthesis of Zn-doped MoO3 nanoribbons with excellent triethylamine sensing performance. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 35(12), 871 (2024).

Tian, R., Ding, Y., Wang, Q. & Song, P. Advanced triethylamine sensor utilizing 3D microspheres of La-doped MoO3: performance enhancement and mechanism insights. Sens. Actuators B 412, 135817 (2024).

Tan, X. et al. High performance and highly selective sensing of triethylamine sensors based on Cu-doped MoO3 nanobelts. J. Alloys Compd. 976, 173152 (2024).

Tan, X. et al. Ultrasensitive triethylamine gas sensors with ZnSe nanospheres/nest-like Cr-doped MoO3. J. Hazard. Mater. 474, 134709 (2024).

Chen, X., Liu, T. & Yin, X-T. High response triethylamine gas sensor based on flaky W-doped MoO3. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 129, 691–698 (2024).

Shen, J. et al. Synthesis of Ni-doped α-MoO3 nanolamella and their improved gas sensing properties. Sens. Actuators B. 252, 757–763 (2017).

Phuruangrat, A., Thipkonglas, S., Thongtem, T. & Thongtem, S. Hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of Dy-doped MoO3 nanobelts for using as a visible-light-driven photocatalyst. Mater. Lett. 195, 37–40 (2017).

Phuruangrat, A., Cheed-Im, U., Thongtem, T. & Thongtem, S. High visible light photocatalytic activity of Eu-doped MoO3 nanobelts synthesized by hydrothermal method. Mater. Lett. 172, 166–170 (2016).

Farid, H. M. T. et al. Ce-doped MoO3 photocatalyst as an environmental purifier for removal of noxious rhodamine B organic pollutant in wastewater. Energy Technol. 11(7), 2300116 (2023).

Bashir, S., Habib, A., Jamil, A., Alazmi, A. & Shahid, M. Fabrication of Ag-doped MoO3 and its nanohybrid with a two-dimensional carbonaceous material to enhance photocatalytic activity. Adv. Powder Technol. 33(3), 103482 (2022).

Car, T., Jakovac, I., Šarić, I., Bernstorff, S. & Micetic, M. Structural, Optical and Electrical properties of Al + MoO3 and au + MoO3 thin films prepared by Magnetron Codeposition. Materials. 14(4), 766 (2021).

Abdellaoui, A., Martin, L. & Donnadieu, A. Structure and optical properties of MoO3 thin films prepared by chemical vapor deposition. Phys. Status Solidi (a) 109(2), 455–462 (1988).

Khalid, N. R. et al. Investigation of novel, green synthesized and photocatalytic Sn-doped MoO3 nanomaterial for the degradation of methyl orange. Optik 300, 171637 (2024).

Balaji, M., Chandrasekaran, J., Raja, M. & Rajesh, S. Structural, optical and electrical properties of Ru doped MoO3 thin films and its P–N diode application by JNS pyrolysis technique. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 27(11), 11646–11658 (2016).

Lee, Y-S. et al. Spray pyrolysis-based synthesis of pure molybdenum powder with nanoscale primary particles and its sintering characteristics. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 118, 106492 (2024).

Vijayan, K. et al. A review on advancements, challenges, and prospective of copper and non-copper based thin-film solar cells using facile spray pyrolysis technique. Sol. Energy 234, 81–102 (2022).

Kamoun, O., Boukhachem, A., Amlouk, M. & Ammar, S. Physical study of Eu doped MoO3 thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 687, 595–603 (2016).

Pandeeswari, R. & Jeyaprakash, B. G. Nanostructured α-MoO3 thin film as a highly selective TMA sensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 53, 182–186 (2014).

Li, P-H. et al. Electrons in oxygen vacancies and oxygen atoms activated by Ce3+/Ce4 + promote high-sensitive electrochemical detection of pb(II) over Ce-doped α-MoO3 catalysts. Anal. Chem. 92(24), 16089–16096 (2020).

Giba, A. E. et al. Strong room temperature blue emission from rapid thermal annealed cerium-doped aluminum (oxy)nitride thin films. ACS Photonics 4(8), 1945–1953 (2017).

Balaji, M., Chandrasekaran, J., Raja, M. & Marnadu, R. Impact of Cu concentration on the properties of spray coated Cu-MoO3 thin films: evaluation of n-CuMoO3/p-Si junction diodes by J-V, Norde and Cheung’s methods. Mater. Res. Express 6(10), 106404 (2019).

Munawar, T. et al. Rational design and electrochemical validation of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) supported CeO2-Nd2O3/rGO ternary nanocomposite as an efficient material for supercapacitor electrodes. J. Appl. Electrochem. 53(9), 1853–1868 (2023).

Sen, S. K. et al. Estimation of hydrothermally synthesized Iron incorporated 2D-sheet-like α-MoO3 microstructural and optical parameters treated by annealing temperature. Mater. Res. Express 7(9), 095005 (2020).

Tataroğlu, A. Electrical and dielectric properties of MIS Schottky diodes at low temperatures. Microelectron. Eng. 83(11), 2551–2557 (2006).

Gunavathy, K. V., Tamilarasan, K., Rangasami, C. & Arulanantham, A. M. S. Effect of solvent on the characteristic properties of nebulizer spray pyrolyzed Cu2ZnSnS4 absorber thin films for photovoltaic application. Thin Solid Films 697, 137841 (2020).

Jendoubi, I., Ben Smail, R., Maczka, M. & Zid, M. F. Optical and electrical properties of the yavapaiite-like molybdate NaAl(MoO4)2. Ionics 24(11), 3515–3533 (2018).

Al-Hardan, N. H., Abdullah, M. J. & Aziz, A. A. Sensing mechanism of hydrogen gas sensor based on RF-sputtered ZnO thin films. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 35(9), 4428–4434 (2010).

Chakraborty, M., Kadir, E. S. & Gayen, R. N. GO induced grain-boundary modification in transparent TiO2-GO nanocomposite thin films: study by DC bias dependent impedance spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 808, 140116 (2022).

Troncoso, L., Alonso, J. A. & Aguadero, A. Low activation energies for interstitial oxygen conduction in the layered perovskites La1 + xSr1 – xInO4 + δ. J. Mater. Chem. A 3(34), 17797–17803 (2015).

Patil, S. J., Lokhande, V. C., Lee, D-W. & Lokhande, C. D. Electrochemical impedance analysis of spray deposited CZTS thin film: Effect of Se introduction. Opt. Mater. 58, 418–425 (2016).

Layegh, M., Ghodsi, F. E. & Hadipour, H. Improving the electrochemical response of nanostructured MoO3 electrodes by Co doping: synthesis and characterization. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 121, 375–385 (2018).

Sankir, N. D., Aydin, E. & Sankir, M. Impedance spectroscopy and dielectric properties of silver incorporated indium sulfide thin films. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 9(7), 3864–3875 (2014).

Khalid, N. R. et al. Green synthesized, photocatalytic co-doped MoO3 nanospheres for wastewater treatment. Ceram. Int. 50(6), 9640–9649 (2024).

Aadil, M. et al. Facile synthesis of binary metal substituted copper oxide as a solar light driven photocatalyst and antibacterial substitute. Adv. Powder Technol. 32(3), 940–950 (2021).

Nadeem, M. S. et al. Synergistic photocatalytic properties of fullerene (C60) anchored V/Cu dual-doped NiO nanocomposites for water disinfection. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 297, 116705 (2023).

Mukhtar, F. et al. Highly efficient tri-phase TiO2–Y2O3–V2O5 nanocomposite: structural, optical, photocatalyst, and antibacterial studies. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 12(4), 547–564 (2022).

Paul, M., Dhanasekar, M. & Bhat, S. V. Silver doped h-MoO3 nanorods for sonophotocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants in ambient sunlight. Appl. Surf. Sci. 418, 113–118 (2017).

Nadeem, M. S. et al. Facile synthesis of PANI and rGO supported Y/Pr co-doped ZnO: boosted solar light-driven photocatalysis. Appl. Phys. A 129(6), 450 (2023).

Mahalingam, S., Ramasamy, J. & Ahn, Y-H. Synthesis and application of graphene-αMoO3 nanocomposite for improving visible light irradiated photocatalytic decolorization of methylene blue dye. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 80, 276–285 (2017).

Do, J. Y. et al. Selective methane production from visible-light-driven photocatalytic carbon dioxide reduction using the surface plasmon resonance effect of superfine silver nanoparticles anchored on lithium titanium dioxide nanocubes (Ag@LixTiO2). Appl. Catal. B 237, 895–910 (2018).

Navgire, M. E. et al. Effect of poly(ethylene glycol) surfactant on carbon-doped MoO3nanocomposite materials and its photocatalytic activity. Bull. Mater. Sci. 34(3), 535–541 (2011).

Bibi, S. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of malachite green and methylene blue over reduced graphene oxide (rGO) based metal oxides (rGO-Fe3O4/TiO2) nanocomposite under UV-visible light irradiation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9(4), 105580 (2021).

Yu, J., Zhao, X. & Zhao, Q. Effect of film thickness on the grain size and photocatalytic activity of the sol-gel derived nanometer TiO2 thin films. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 19, 1015–1017 (2000).

Lima, C. D. A. et al. Co-doped α-MoO3 hierarchical microrods: synthesis, structure and phonon properties. Ceram. Int. 47 (19), 27778–27788 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.K. did the synthesis and analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript text, A.A. did the structural characterization and prepared the associated figures and tables, B.A. performed characterization and prepared the associated figures and tables, N.T-K did supervision of synthesis and characterization, and R.V. assisted in the data analysis, reviewing the results and writing the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kamoun, O., Akkari, A., Alhalaili, B. et al. Investigations on the synthesis and characterization of silver-doped MoO3 thin films for photocatalytic applications. Sci Rep 15, 998 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84485-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84485-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Structural, morphological, optical, and photocatalytic properties of MgO and Cu-MgO thin films prepared using sol-gel spin coating

Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology (2025)

-

Growth of molybdenum oxide (α-MoO3) layers through proximity evaporation: studying electronic properties and photo-responsivity

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2025)