Abstract

The depletion of oil reserves and their price and availability volatility raise researchers’ concerns about renewable resources for epoxidized material. This study aims to produce in situ and ex-situ hydrolyzed dihydroxy stearic acid via the epoxidation of neem oil. Epoxidized neem oil was synthesized using in situ-generated performic acid. The Taguchi method was employed to optimize hydrolysis, aiming for maximum production of dihydroxystearic acid. The Taguchi method’s signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio analysis identified optimal conditions for producing dihydroxy stearic acid with a maximum hydroxyl value of 129.4 mg KOH/g: (1) water/neem oil molar ratio of 2:1, (2) water addition time of 90 min, and (3) reaction stop time of 120 min. ANOVA revealed the significant order of parameters as reaction stop time > water addition time > water/neem oil molar ratio. Lastly, a mathematical model was developed using MATLAB, applying the fourth-order Runge–Kutta method and simulated annealing optimization to determine the best-fitting kinetic model. This research aids in transforming neem oil into a value-added product, reduces petroleum dependence, and provides key insights into reaction kinetics for industrial applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renewable resource utilization is a major research focus, with vegetable oils being key alternatives to petrochemicals. Neem oil, rich in unsaturated fatty acids like oleic, linoleic, and linolenic acids, offers modifiable C = C bonds for chemical or enzymatic processes1. Epoxides were once petroleum-based, but using neem oil offers a renewable alternative. Neem oil is a versatile base material, and its oleic acid can be converted into valuable raw materials. Epoxidized vegetable oils are increasingly used as precursors for synthesizing chemicals like alcohols2, glycols3, and polymers4. In situ, epoxidation involves the formation of performic acid by mixing oxygen donor and oxygen carrier, which are hydrogen peroxide and formic acid, respectively5. The instability of oxirane rings allows for further chemical modifications, such as converting them into dihydroxy stearic acid (DHSA) via hydrolysis. DHSA is produced by hydrolyzing epoxidized vegetable oils, using water from the by-product of the oxidizing agent in the peracid mechanism6.

The Taguchi method, developed by Genichi Taguchi, optimizes process parameters to enhance quality and reduce variability7. This study produced DHSA from epoxidized neem oil through a hybrid in situ and ex-situ hydrolysis, extending the epoxidation to 300 min. Additional water was needed to increase DHSA hydroxyl content. The high reactivity of the oxirane ring in epoxidized neem oil allows for the synthesis of dihydroxy stearic acid, a hydroxyl fatty acid with one carboxyl and two hydroxyl groups. To achieve a high hydroxyl value for industrial use, transesterification of vegetable oils is performed before epoxidation8. Arniza M et al. demonstrated that transesterification with glycerol enhances functionality by adding an extra hydroxyl group9. However, this process is time-consuming and resource-intensive, taking 360 min and requiring multiple chemical steps. Holser R. noted that without transesterification, DHSA production after a 120 min epoxidation results in lower hydroxyl group quantities, possibly due to insufficient by-product water acting as an oxygen donor10. Neem oil’s unique properties make it a strong candidate for bio-polymer and resin production. Due to azadirachtin and triterpenoids, its high oxidative stability reduces the need for stabilizers, cutting costs and extending product life. Unlike soybean oil, neem oil’s fatty acid profile provides flexibility and compatibility in resin formulations while offering better durability than linseed oil11. These qualities give neem oil an edge in applications requiring stable, long-lasting bio-polymers, highlighting its potential as a sustainable feedstock.

DHSA from neem oil was produced to maximize the potential of neem oil in the market, other than currently used pesticides and alternative medicine. DHSA is a compound of significant industrial value, with applications across various sectors due to its functional hydroxyl groups. These make it ideal for roles requiring thickening, plasticization, or bio-based alternative chemicals. DHSA is extensively used in lubricants, cosmetics, and polymer synthesis8. Current DHSA production methods are hindered by catalytic epoxidation and hydrolysis inefficiencies, leading to low epoxide selectivity, undesirable byproducts, and reduced yields. These processes rely on costly catalysts, high energy inputs, and harsh chemicals, resulting in environmental challenges and scalability issues. Additionally, hydrolysis may be inefficient if the oil substrate lacks optimal epoxide content, further complicating cost-effectiveness and production feasibility. Thus, a hybrid approach of in situ and ex-situ hydrolysis is employed, where water is added after the degradation of the oxirane ring. The objectives of this study are: (1) to optimize process parameters and evaluate the performance of DHSA production using a hybrid of in situ and ex-situ hydrolysis of epoxidized neem oil, and (2) to develop a process model for DHSA production using the fourth-order Runge-Kutta method to determine the reaction kinetics.

Method

Materials

Neem oil, Hydrogen peroxide 50%, formic acid 85%, glacial acetic acid, and hydrobromic acid are supplied by Qrec Sdn. Bhd; meanwhile, amber lite IR 120 H catalysts are by Supelco Sdn. Bhd. Neem oil is composed primarily of fatty acids, with a significant portion being unsaturated, making it suitable for reactions like epoxidation. The major fatty acids in neem oil include oleic acid (40%), linoleic acid (11%), and palmitic acid (45%).

Formation of DHSA from epoxidized neem oil by hybrid in situ and ex-situ hydrolysis

For the epoxidation method, 100 g of neem oil was mixed with molar ratios of hydrogen peroxide and formic acid to neem oil (1:1.5:1) in a 500-mL water-bathed beaker. The beaker, equipped with a magnetic stirrer on a hot plate, was stirred at 350 rpm and heated to 75 °C. DHSA is formed due to the oxirane ring opening by the hydrolysis process by water since it is readily available in the reaction before the by-product of performic acid formation used for the epoxidation process of neem oil earlier12. This reactor is set to operate under isothermal conditions with a controlled temperature setting. This study focuses on the hybrid of ex-situ and in-situ hydrolysis, where water is added during the degradation of an epoxide ring. The process starts with the epoxidation of neem oil to create an epoxide intermediate. In the in-situ phase, water is introduced directly into the reaction mixture, facilitating hydrolysis of the epoxide ring and forming hydroxyl groups to boost the reaction rate and DHSA yield. Following this, the ex-situ phase allows further optimization by adjusting water concentration separately, enabling precise control over hydrolysis and minimizing byproducts. By integrating the direct reactivity of in-situ hydrolysis with the precision of ex-situ adjustments, this approach aims to achieve efficient and scalable DHSA production. There are three parameters, and each has four levels, as tabulated in Table 1.

Samples were analyzed using the hydroxyl value test to monitor reaction progress and assess DHSA yield, providing a quantitative measure of hydroxyl group formation as the epoxide ring opens during hydrolysis. This test enables precise tracking of the conversion to DHSA, allowing for adjustments in reaction conditions to optimize yield and ensure process consistency. The diversity of factors was examined using the orthogonal array of control parameters (Table 2). Results from the L16 experimental runs were analyzed using the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio and ANOVA. The Taguchi method predicted optimal reaction conditions, which were then validated through a confirmation reaction13.

Relative conversion oxirane (RCO)

Every 5 min, 3 g of the sample were titrated with 10 ml of acetic acid and crystal violet with HBr for oxirane content analysis (AOCS Cd 957)14. Titration continued until the highest RCO was achieved, then epoxidation proceeded until RCO decreased, indicating DHSA formation, and stopped at 120 min. The color change from blue to yellow indicates the oxirane ring formation. The volume of HBr and sample weight were used to calculate the experimental OOC, which is used to determine RCO. RCO is calculated from OOC values based on theoretical and experimental equations based on Eqs. (1–3).

Here, \(\:{X}_{0}\) is the initial iodine value, \(\:{\text{A}}_{\text{i}}\) is the molar mass of iodine, \(\:{A}_{o}\) Is the molar mass of oxygen, \(\:N\:\)is the normality of HBr, \(\:V\) is the volume of the HBr solution used for the blank in millilitres (mL), \(\:V\) is the volume of HBr solution used for titration, and \(\:W\) is the weight of the sample.

Kinetic modelling epoxidation of neem oil

A kinetic study based on finding a rate constant for each reaction involved in epoxidation and hydrolysis of neem oil is shown in Eqs. (4–6) where FA, HP, PFA, NO, and ENO are formic acid, hydrogen peroxide, performic acid, neem oil and epoxidized neem oil consecutively. This model assumes all reactants, intermediates, and products are in a single liquid phase, eliminating phase boundary effects and mass transfer limitations. It also assumes constant temperature, pressure, and ideal mixing, ensuring uniform concentration and stable reaction rates, which simplifies the analysis and allows the Runge–Kutta method to focus solely on reaction kinetics in a homogeneous system. However, the model’s constraints include accurate reaction kinetics, controlled time steps for Runge–Kutta, and energy limits in simulated annealing to prevent premature convergence, with convergence criteria ensuring reliable results.

A novel genetic algorithm was developed and applied to solve ordinary differential equations. The data for FA, HP, and NO were obtained experimentally. ENO and other intermediates like PFA reach constant levels, indicating that the reaction rates of the reversible steps are balanced. Therefore, this steady-state condition supports the idea that the final step drives ENO to DHSA irreversibly. In reaction kinetics modeling, assuming irreversibility for the final step can simplify the system of equations, making the model easier to solve and interpret. This self-learning system is intrinsically parallel and can handle linear and nonlinear equations15. Genetic algorithms are a key element in artificial intelligence and machine learning, playing a significant role in optimization and kinetic study16. The rate and simultaneous differential equations are provided in Eqs. (7–13).

Kinetic modeling involves (1) numerically solving rate equations using MATLAB’s ode45 solver with the fourth-order Runge–Kutta method and (2) minimizing the error e between simulation and experimental values. The error function e is given by Eq. 14.

Where \(\:{\text{ENO}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{sim}}\) and \(\:{\text{ENO}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{exp}}\) denote the estimated and experimental epoxide concentrations, \(\:i\) is the ith data point, and \(\:n\) is the total number of data points in the simulations and experiments.

Results and discussion

Optimization by Taguchi method

The Taguchi method uses statistical analysis to identify the factors that contribute most to the variability in the output and then optimizes the process so that these factors are minimized17. This method has been applied to many products and processes, including electronics, automobiles, and consumer goods. Orthogonal array significantly reduces the number of experimental configurations to be studied, which will likely be implemented in the manufacturing industry since it would reduce the cost. The effect of many different parameters on a process’s performance characteristics can be defined using the orthogonal array experimental design proposed by Taguchi18. In general, a higher S/N ratio indicates better performances, thus providing info on the influence of each factor contributing to the optimum response. Therefore, optimum levels for all process parameters are the level with the highest S/N ratio19. The hydroxyl values for each set-up of neem oil epoxidation are presented in Table 3.

The S/N ratios were plotted for each of the three levels of parameters stated, as shown in Fig. 1. Based on the plot, it can be concluded that the hydroxyl value was maximum at the following: (1) water/neem oil molar ratio of 2:1, (2) water addition time of 90 min, and (3) reaction stop time of 120 min. The S/N ratio produces a higher epoxidation rate of neem oil to produce DHSA, with the highest hydroxyl value of 129.4 mg KOH/g. The OH value obtained using the in situ method alone was 90.8 mg KOH/g, while the maximum OH value achieved with the hybrid in situ and ex-situ approach reached 129.4 mg KOH/g. This substantial increase in OH value confirms that DHSA was successfully produced by combining in-situ and ex-situ hydrolysis methods. The higher OH value in the hybrid approach demonstrates more effective hydroxylation, validating the advantage of using both methods to maximize DHSA yield. The S/N ratio indicates that these parameters enhance the epoxidation rate of neem oil, leading to increased production of dihydroxy stearic acid. A high hydroxyl value indicates a higher concentration of hydroxyl groups in the product, which can enhance its functionality in various applications20. In epoxidation and hydrolysis, a high hydroxyl value signifies the effective conversion of the epoxide groups to dihydroxy stearic acid, making the product more valuable and suitable for industrial uses.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA)

ANOVA is a statistically based, objective decision-making tool for detecting differences in the average performance of group items tested. ANOVA helps identify the significance of all the main factors and their interaction by comparing the mean square against an estimate of the experimental errors at specific confidence levels21. ANOVA classifies the effect of each factor (process parameters) on the significant response. The sum of square deviations from the total mean of the response separates each level’s total variability22. The ANOVA results obtained from the epoxidation of neem oil are tabulated in Table 4. The time to stop reaction was the most significant factor affecting the DHSA production (48.3%). This factor has the highest influence because it determines the reaction’s duration, affecting the extent of epoxidation and hydrolysis. Stopping the reaction at the optimal time ensures maximum conversion of epoxide groups to DHSA without over-processing, which can lead to side reactions or degradation. The time to water addition affected it by 34.44 and water to neem oil molar ratio by 17.3%. The water-to-neem oil molar ratio is still important, but this factor has a lesser impact than the other two. The ratio affects water availability relative to neem oil. Still, its influence is secondary to the timing of addition and reaction stopping, which are critical for optimizing the reaction conditions.

DHSA production via hybrid in situ and ex-situ hydrolysis

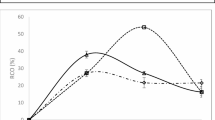

The ring opening of epoxidized material is crucial to producing precursor material for other products. Salimon et al. had. Utilise this concept by promoting the ring opening of epoxidized linoleic acid to bio-based lubricants23. On the other hand, Ismail et al. produce dihydroxy stearic acid (DHSA) by ring opening of epoxidized oleic acid, which can be used as a raw material for producing cosmetic products24. Figure 2 below shows the pattern of relative conversion oxirane percentage (RCO%) from the epoxidation process of the neem oil with continuous in situ and ex-situ hydrolysis of epoxidized neem oil until two hours where the RCO decreases, which indicates the oxirane ring opening had occurred.

The highest RCO% at 70 min indicates the highest epoxidation rate, with the highest oxirane ring forming. After that, RCO% decreases with time, indicating that oxirane oxygen content reduces due to the oxirane ring’s degradation. This occurs because of the three-atom ring’s carbon and oxygen bond cleavage. The position of the three atoms approaching an equilateral triangle would tense the bonds, increasing their reactivity. Epoxidation is an electrophilic process where peroxyacid transfers an oxygen atom to the alkene, forming (C-O) bonds on the same side of the double bond in one step, without intermediates. The oxygen atom is transferred farthest from the carbonyl group. With an extra reactive oxygen atom, Peracid attacks the alkene, displacing the carboxylate group. This process involves electrophilic attack and proton transfer, making the reaction time crucial for optimizing DHSA production.

Catalyst recycling

Catalyst recycling is the process of recovering and reusing catalysts after a chemical reaction, improving the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of industrial processes25. Efficient recycling reduces the need for fresh catalyst material and minimizes waste, especially when expensive or rare materials are used. In this study, the effectiveness of reusability of Amberlite IR 120 H as a catalyst is measured by determining the relative conversion oxirane (RCO) for each time the catalyst is used. Recycling catalysts helps conserve valuable resources and lowers operational costs. By reusing catalysts, industries can avoid the continuous purchase of new materials, thus reducing both financial and environmental impacts. Amberlite, a heterogeneous catalyst, is effective in aqueous hydrogen peroxide and reduces the acidity of epoxide yield. The epoxidation process involves (1) reversible production of peroxy acid from hydrogen peroxide in water with a strong acid catalyst, (2) transfer of both organic acid and peracid to the organic phase based on their partition coefficients, and (3) epoxidation in the organic phase to form the epoxide.

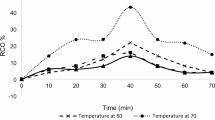

Catalysts are filtered after each epoxidation and washed with acetone, followed by water thoroughly to remove the excess solution. After that, the drying process is weighted to determine if catalyst loss exists. This step is repeated before each epoxidation process. RCO) measures how efficiently the catalyst facilitates the formation of epoxide groups in the reaction. Tracking RCO for each reuse cycle, the study evaluates the catalyst’s performance and stability over time. Decreases in relative conversion oxirane are observed after a second run at 5%, a third run at 17% and a fourth run at 34% from the first run. The decreasing trend is shown in Fig. 3. Recycling is especially important in processes using rare or expensive catalysts, such as platinum.

Numerical kinetics model of EPOA production

Kinetic modeling is essential for optimizing the epoxidation process, allowing for predicting reaction rates and estimating residence times required for desired conversion levels. This study used MATLAB to model the kinetics of hybrid oil epoxidation, employing the genetic algorithm to fit experimental data and the Runge-Kutta Fourth Order method (ode45) to solve differential equations. By leveraging advanced numerical techniques like genetic algorithm and ode45 in MATLAB, this study provides a robust framework for accurately modeling and predicting the kinetics of epoxidation, offering a valuable tool for process optimization.

The results show that the performic acid formation (k12) reaction rate is lower than its reverse reaction (k11), indicating faster epoxide production, as shown in Table 5. This implies that the reverse reaction of performic acid formation is faster than the forward one, which is significant because performic acid acts as an intermediate in the epoxidation process. Compared to previous studies, the kinetic values for hybrid oil epoxidation are consistent within reported ranges, though oxirane ring degradation occurs earlier. The kinetic values derived for the epoxidation of hybrid oil are within the ranges reported by previous studies26. This suggests that the model developed using MATLAB is robust and reliable for predicting the behaviour of hybrid oils in the epoxidation process.

Figure 4 compares experimental and simulated EPOA concentrations at the optimal temperature of 100 °C, showing close alignment with a ~ 0.20 difference. However, deviations occur between 30 and 40 min because the simulation assumes ideal conditions without accounting for heat loss or mass transfer limitations. In contrast, the experimental setup may experience heat loss, temperature gradients, and system inefficiencies that the model does not capture. Since the simulations rely solely on chemical reaction equations under ideal conditions, practical limitations in the experiment, such as non-uniform heating and imperfect insulation, contribute to these differences.

Conclusion

DHSA has become a valuable industrial product due to neem oil’s renewable and eco-friendly nature. This study epoxidized oleic acid from neem oil using in situ generated performic acid to produce DHSA. The highest hydroxyl value (129.4 mg KOH/g) was achieved with a water/neem oil ratio of 2:1, water addition for 90 min, and a reaction stop time of 120 min. ANOVA indicated that the reaction stop time was the most significant factor in the hybrid hydrolysis of epoxidized neem oil. There was a good fit between experiment and simulation values of optimum condition with the slightest difference of ~ 0.20 based on the kinetics study attained. Although the study’s objectives were met, further research could explore additional value-added uses for epoxides after the ring opening of epoxidized neem oil. These include potential industrial applications of DHSA, particularly in the lubricant, polymer, and adhesive industries, where its properties could offer substantial benefits. Furthermore, investigating the adaptation of this process for various biomass oils, such as linseed and castor oil, enhances the methodology’s flexibility and optimizes epoxide yields across different feedstocks.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chaudhari, A., Gite, V., Rajput, S., Mahulikar, P. & Kulkarni, R. Development of eco-friendly polyurethane coatings based on neem oil polyetheramide. Ind. Crops Prod. 50, 550–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.08.018 (2013).

Ekkaphan, P., Sooksai, S., Chantarasiri, N. & Petsom, A. Bio-based polyols from seed oils for water-blown rigid polyurethane foam preparation. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/4909857 (2016).

American, L. Preparation of oleochemical polyols derived from soybean oil. 74 69–74. (2011).

Soloi, S., Majid, R. A. & Rahmat, A. R. Novel palm oil based polyols with amine functionality synthesis via ring opening reaction of epoxidized palm oil. J. Teknol 80, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.11113/jt.v80.11062 (2018).

Kamairudin, N., Hoong, S. S., Abdullah, L. C., Ariffin, H. & Biak, D. R. A. Optimisation of epoxide ring-opening reaction for the synthesis of bio-polyol from palm oil derivative using response surface methodology. Molecules 26 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26030648 (2021).

Article, R. Palm dihydroxystearic acid (DHSA): a multifunctional ingredient for various applications. 27 (2015).

Aydoğmuş, E. & Kamişli, F. New commercial polyurethane synthesized with biopolyol obtained from canola oil: optimization, characterization, and thermophysical properties. J. Mol. Struct. 1256 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.132495 (2022).

Jumain Jalil, M., Azfar Izzat Aziz, M., Nuruddin Azlan Raofuddin, D., Suhada Azmi, I. & Heiry Mohd Azmi, M. Saufi Md. Zaini, I. Mariah Ibrahim, Ring-opening of epoxidized waste cooking oil by hydroxylation process: optimization and kinetic modelling. ChemistrySelect 7, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202202977 (2022).

Arniza, M. Z. et al. Synthesis of transesterified palm olein-based Polyol and rigid polyurethanes from this polyol. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 92, 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11746-015-2592-9 (2015).

Della Bella, L. G. Rivolta, dihydroxystearic acid using a solid catalyst, XCIII (2016).

Rasib, I. M., Mubarak, N. M., Azmi, I. S. & Jalil, M. J. Epoxidation of neem oil via in situ peracids mechanism with applied ion exchange resin catalyst. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-024-06137-5 (2024).

Habri, H. H., Azmi, I. S., Mubarak, N. M. & Jalil, M. J. Auto-catalytic epoxidation of oleic acid derived from palm oil via in situ performed acid mechanism. Catal. Surv. Asia. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10563-023-09398-8 (2023).

Patyal, V. S., Modgil, S. & Maddulety, K. Application of Taguchi method of experimental design for chemical process optimisation: a case study. Asia-Pacific J. Manag Res. Innov. 9, 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319510X13519320 (2013).

Lye, Y. N., Salih, N. & Salimon, J. Optimization of partial epoxidation on jatropha curcas oil based methyl linoleate using urea-hydrogen peroxide and methyltrioxorhenium catalyst. Appl. Sci. Eng. Prog 14, 89–99. https://doi.org/10.14416/J.ASEP.2020.12.006 (2021).

Roberts, J., Bursten, J. R. S. & Risko, C. Genetic algorithms and machine learning for Predicting Surface Composition, structure, and Chemistry: a historical perspective and Assessment. Chem. Mater. 33, 6589–6615. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.1c00538 (2021).

Jalil, M. J., Azmi, I. S. & Hadi, A. Highly production of dihydroxystrearic acid from catalytic epoxidation process by in situ peracid mechanism. Environ. Prog Sustain. Energy. 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ep.13764 (2021).

Lan, T. S., Chuang, K. C. & Chen, Y. M. Optimization of machining parameters using Fuzzy Taguchi method for reducing tool wear. Appl. Sci. 8, 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8071011 (2018).

Wilson, V. H. Optimization of diesel engine parameters using Taguchi method and design of evolution, XXXIV 423–428. (2012).

Karanfil, G. Importance and applications of DOE/optimization methods in PEM fuel cells: a review. Int. J. Energy Res. 44, 4–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.4815 (2020).

Dhaliwal, G. S., Anandan, S., Chandrashekhara, K., Lees, J. & Nam, P. Development and characterization of polyurethane foams with substitution of polyether polyol with soy-based polyol. Eur. Polym. J. 107, 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2018.08.001 (2018).

Prasad, K. S., Rao, C. S. & Rao, D. N. Study on factors effecting Weld pool geometry of pulsed current micro plasma arc welded AISI 304L austenitic stainless steel sheets using statistical approach. J. Min. Mater. Charact. Eng. 11, 790–799. https://doi.org/10.4236/jmmce.2012.118068 (2012).

Chen, W. H. et al. A comprehensive review of thermoelectric generation optimization by statistical approach: Taguchi method, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and response surface methodology (RSM). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 169, 112917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112917 (2022).

Performik, A., Hong, L. K., Yusop, R. M., Salih, N. & Salimon, J. Optimization of the in situ epoxidation of linoleic acid of Jatropha curcas oil with performic acid. Malaysian J. Anal. Sci. 19, 144–154 (2015).

Ismail, K. N. et al. High yield dihydroxystearic acid (DHSA) based on kinetic model from Epoxidized Palm Oil. Kem u Ind. 70, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.15255/kui.2020.016 (2021).

Marriam, F., Irshad, A., Umer, I. & Arslan, M. Vegetable oils as bio-based precursors for epoxies. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 31, 100935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2022.100935 (2023).

de Haro, J. C., Izarra, I., Rodríguez, J. F., Pérez, Á. & Carmona, M. Modelling the epoxidation reaction of grape seed oil by peracetic acid. J. Clean. Prod. 138, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.05.015 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ismail Md Rasib: Writing and experiment work; Intan Suhada Azmi: Data curation; Mohd Jumain Jalil: conceptualization and methodology. Nabisab Mujawar Mubarak: Review and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rasib, I.M., Jalil, M.J., Mubarak, N. et al. Hybrid in-situ and ex-situ hydrolysis of catalytic epoxidation neem oil via a peracid mechanism. Sci Rep 15, 147 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84541-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84541-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Catalytic epoxidation of oleic acid through in situ hydrolysis for biopolyol formation

Scientific Reports (2025)