Abstract

Patients at high risk of deep vein thrombosis are recommended to undergo lower-extremity ultrasonography to screen for pulmonary embolism (PE); however, there are few reports on whether this can effectively reduce the occurrence of fatal pulmonary embolism (FPE). This study aimed to assess the risk factors associated with PE and to investigate whether perioperative ultrasound screening of lower extremity veins in orthopedic patients can effectively reduce the incidence of FPE. We enrolled 137 patients with PE who underwent orthopedic surgery between 2013 and 2020. Patients were divided into survival and non-survival groups based on whether FPE occurred during hospitalization. Demographic and clinical data were compared between groups. Ultrasound screening was effective in reducing the incidence of FPE in orthopedic patients. Thrombolytic therapy and computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) were highlighted factors that protect against FPE. Coronary heart disease was found to be independent risk factors for FPE. Proximal thrombus associated with an FPE. Ultrasound screening of the lower limb veins should be routinely performed in orthopedic patients during the perioperative period. Prophylactic inferior vena cava filter implantation, thrombolytic therapy, and CTPA can be performed in patients with suspected PE to reduce its incidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In deep vein thrombosis (DVT), 90% of emboli develop in the lower extremities or pelvic region1; therefore, preventive screening of these areas is fundamental2. Commonly employed screening methods include lower-extremity Doppler ultrasonography and venography. This latter methodology is considered the gold standard for diagnosing DVT but presents issues such as invasiveness, restricted applicability, and lack of repeatability3. Therefore, in clinical practice, non-invasive venous ultrasonography of both lower limbs has become the preferred examination for evaluating clinically suspected DVT4. Ultrasonography has an overall sensitivity and specificity of 95% and 92%, respectively, for diagnosing DVT; thus, it is a reasonable alternative to venography5,6. Patients at high risk of DVT are recommended to undergo lower-extremity ultrasonography as an initial screening method for pulmonary embolism (PE)7; however, there are few reports on whether this can effectively reduce the occurrence of fatal pulmonary embolism (FPE). In addition, while some studies have exclusively focused on ultrasound screening for proximal thrombi8, others have shown no significant difference in the incidence of PE between patients with proximal and distal thrombosis9,10.

Therefore, we retrospectively analyzed the incidence of PE in orthopedic inpatients to explore the associated risk factors and to assess whether ultrasound screening of the venous system of the lower extremities can effectively prevent FPE.

Methods

Patient selection

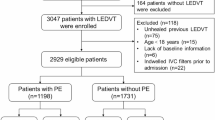

This retrospective study was conducted in our hospital between 2013 and 2020. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) orthopedic surgery performed at our hospital; (2) PE diagnosed through symptoms (the typical PE triad of symptoms or other symptoms such as severe hypoxia, cyanosis, cough, syncope, and palpitation) and/or imaging (computed tomography (CT), contrast-enhanced CT, and CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA)) during hospitalization; and (3) complete case data available. Patients who did not undergo orthopedic surgery, did not have a medically recorded diagnosis of PE, or did not have complete medical records were excluded.

The Ethics Committee of the Xi’an Honghui Hospital approved this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association.

Diagnosis of DVT and PE

Color Doppler ultrasonography of the lower limb veins was the standard method for diagnosing DVT. Ultrasound screening was performed between days 1 and 3 after admission and postoperative days 3 and 4. DVT was diagnosed if the following criteria were met10: (1) the venous lumen could not be closed; (2) low echo or no echo was observable within the lumen; (3) a small or no blood flow signal was detected in the vein of the thrombus segment; (4) no blood flow was observed through pulse Doppler or blood flow did change with respiration; (5) DVT located in the popliteal vein and proximal to the popliteal vein was defined as proximal thrombi and DVT located distal to the popliteal vein was defined as distal thrombi11; and (6) clinical symptoms such as swelling of the affected limb, pain on pressure, and fever.

First, a diagnosis of PE was made if the following clinical criteria were met: (1) obvious induction of PE or other diseases such as venous thrombosis; (2) the typical PE triad of symptoms, namely dyspnea, chest pain, and hemoptysis; and (3) other symptoms such as severe hypoxia, cyanosis, cough, syncope, palpitation, and other symptoms of discomfort. After assessing the severity and risk of death due to PE, the diagnosis was further clarified by imaging. Patients received an imaging diagnosis of PE through CT, contrast-enhanced CT, and CTPA according to the following criteria: (1) for CT, signs of pulmonary artery obstruction, pulmonary hypertension, and right heart enlargement were observed, in addition to wedge-shaped opacity at the hilum of the lungs; (2) for contrast-enhanced CT, a low-density filling defect of the pulmonary artery, underdevelopment of the distal vessels, a greater wedge-shaped opacity of the pulmonary area, and a reduction of the distal vascular branches were observed; and (3) for CTPA, an intraluminal filling defect of the pulmonary artery, pulmonary artery truncation, decreased number of vascular vessels or the presence of non-vascular vessels in the embolic area, and prolonged local arterial phase and delayed venous phase were present.

Blood was drawn from all patients approximately 2 h after admission and on postoperative day 1. Blood analysis was performed using the Sysmex CS-2500 System (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan). D-dimer evaluation was performed via immunoturbidimetry, and D-dimer values ≥ 1.4 mg/L were considered positive. Thrombophilia work-up, specifically for homocysteine, protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III, was not routinely conducted among the patients we enrolled.

When the patients diagnosed with PE had the outcome of in-hospital death due to pulmonary embolism or symptom remission and were discharged after improvement, we stopped the follow-up.

Prevention and treatment of thrombosis

All patients underwent a risk assessment profile thromboembolism (RAPT) after admission. Patients were divided into low-risk groups (RAPT ≤ 5) and medium- and high-risk groups (RAPT > 5). DVT prophylaxis was administered to low-risk patients using mechanical thromboprophylaxis with an intermittent pneumatic compression device. Medium- and high-risk patients received low molecular weight heparin for prophylaxis (4100 U once daily; GlaxoSmithKline Co., UK) and physical prophylaxis. In patients with an urgent need for surgery due to a floating thrombus or proximal thrombi on Doppler ultrasound with a persistently positive D-dimer level, an inferior vena cava filter (IVCF) may be implanted to prevent FPE after consultation with a vascular specialist. In patients with a fresh proximal thrombus occurring within 2 weeks after ultrasound screening and in patients with intermediate-to-high-risk PE diagnosed after CTPA examination, thrombolytic therapy was performed in the absence of contraindications to thrombolysis to prevent the development of FPE. Thrombolysis was performed in patients with urokinase, recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA), or human recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (r-PA). Patients were divided into either survival or non-survival groups according to whether FPE occurred during hospitalization.

Statistics

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 19 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data analysis. Data are presented as means and standard deviations unless otherwise noted. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were performed for categorical variables, as appropriate. Intergroup comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test for continuous variables. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify the independent associations between various risk factors and DVT. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.05.

Results

A total of 137 patients with PE were enrolled in this study, including 70 males and 67 females, with an average age of 62.65 ± 17.53 (17–88) years. A total of 27 deaths, 96 cases of fracture (54 limb fractures, one pelvic fracture, 33 multiple fractures, and eight spinal fractures), and 41 cases of non-fracture (15 osteoarthritis (OA), one bone tumor, and 25 spinal degeneration diseases) were recorded. Our analysis of the PE incidence demonstrated that from 2013 to 2018, the proportion of deaths caused by PE in patients with confirmed PE decreased annually. In our study, prophylactic interventions reduced the rate of FPE to 11.1%; however, this significantly increased in 2019 because of insufficient funding support for DVT screening at our study center. In 2020, the mortality rate decreased significantly with adequate financial support from our research center (Table 1). A total of 31 patients did not undergo ultrasound screening. Of these, 15 did not undergo Doppler ultrasonography due to sudden clinical suspicion of PE, and 16 patients and their families refused to undergo Doppler ultrasonography due to pain or other reasons.

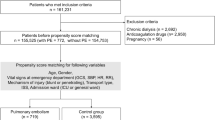

We divided the included cases into survival (n = 110; 16 without ultrasound and 94 with ultrasound screening) and non-survival (n = 27; 15 without ultrasound and 12 with ultrasound screening) groups. After removing non-fracture patients (survival group: n = 74, including 12 without ultrasound and 62 with ultrasound screening; non-survival group: n = 22, including 12 without ultrasound and 10 with ultrasound screening), ultrasound screening was found to effectively reduce the incidence of FPE in orthopedic patients with fracture (p < 0.001) or non-fracture (p < 0.001) concerns (Table 2). Forty patients underwent IVCF implantation to prevent FPE, and none developed FPE. Thirty patients with DVT were treated with thrombolytic therapy, and only one of them developed FPE.

IVCF placement (p < 0.001), thrombolytic therapy (p = 0.013), and CTPA examination (p < 0.001) effectively reduced the occurrence of FPE and were associated with protective factors. Orthopedic surgery (in the survival group, 77 patients underwent orthopedic surgery and 33 patients did not; in the non-survival group, 13 patients underwent orthopedic surgery and 14 patients did not; X2 = 4.593; p = 0.032) and coronary heart disease (in the survival group, 36.36% had coronary heart disease; in the non-survival group, 66.67% had coronary heart disease, X2 = 8.154; p = 0.004) were statistically significant (Table 3). The multivariate analysis showed that the difference in survival between patients with coronary heart disease (Exp (B) = 3.538, p = 0.006, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.431–8.750), as well as the difference in survival between patients who had undergone orthopedic surgery (Exp (B) = 0.392, p = 0.039, 95% CI 0.161–0.953) were significant (Table 4), indicating that coronary heart disease is independent risk factors and orthopedic surgery is independent protective factors for FPE. By analyzing the 106 patients with ultrasound images, DVT of the lower extremities was found in 94 patients (X2 = 1.220, p = 0.269), indicating that DVT is not an independent risk factor for FPE. However, proximal thrombi were strongly associated with the occurrence of FPE (p < 0.001) (Table 5).

Discussion

PE is the third leading cause of mortality in European and North American countries after ischemic heart disease (acute coronary syndrome) and stroke12. In untreated cases, the mortality rate of PE ranges from 25 to 30%13,14. In the United States, the number of deaths attributable to PE is estimated to be 50,000–100,000 per year15; However, there are no relevant large-scale epidemiological reports in China. The PE is thought to arise from the deep venous system. However, recent studies suggest that PE can occur without DVT, inferring that PE can originate de novo (DNPE)16,17. DNPE appears to be more common after trauma, is clinically different from PE subsequent to DVT, and is likely to signify a local reaction to injury or inflammation18. Both DNPE and the combination of DVT with PE deserve to be given serious attention and actively undergo screening and prevention measures. In our study, there were indeed a part of patients with DNPE. These patients had no DVT detected by lower extremity venous ultrasonography but had symptoms of PE. Moreover, some patients could not undergo imaging examinations such as CT or CTPA to confirm the diagnosis due to the rapid deterioration of their conditions and life-threatening situations. For this part of the patients, we will conduct an electrocardiogram examination to differentiate from myocardial infarction. When the electrocardiogram shows ventricular overload signs such as ST-segment elevation accompanied by S1Q3 and generalized T-wave inversion, it highly suggests PE19. However, not all patients underwent electrocardiogram and blood gas analysis examinations. If the patient has been diagnosed with PE through CT or CTPA, we will not repeat the above examinations. Our study highlights that prophylactic interventions can reduce the mortality rate of PE by 11.1%; therefore, measures to prevent PE are important. Many centers use Doppler ultrasonography to routinely screen high-risk trauma patients for lower-extremity DVT. If asymptomatic DVT is detected, therapeutic interventions for PE, including chemoprophylaxis and inferior vena cava filter placement20,21,22, may be initiated early to prevent PE20. Screening for DVT in asymptomatic and high-risk trauma patients is supported and suggested not only by many studies but also by the latest consensus guidelines of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma and ACCP23,24,25,26.

Brasel et al. showed that ultrasound screening is the most cost-effective method for preventing PE in high-risk trauma patients27, whereas other studies have shown that ultrasound screening is not as effective as adherence to preventive programs. Cipolle et al. conducted a retrospective analysis of 253 hospitalized patients, 30 of whom had PE, and concluded that following the National Venous Thromboembolism Prevention Program was more effective than ultrasound screening28. Similarly, Meyer et al. showed that the risk of proximal thrombosis in symptomatic patients with DVT is higher than that in asymptomatic patients, and the cost of ultrasonography is substantial29. Therefore, for cost-effectiveness, they recommended ultrasound screening only in symptomatic patients. Span et al. discouraged routine active screening as it did not benefit 95% of high-risk patients without DVT, and its cost was high30. Similarly, a prospective study by Satiani et al. concluded that routine ultrasound screening was costly and reported that two patients with PE did not benefit from it31. Therefore, ultrasound screening is not generally recommended because it is expensive and the benefits for patients are not sufficiently high. Meanwhile, preventive anticoagulation therapy is cheaper and more in line with the principle of cost-effectiveness than ultrasound screening. Contrary to the aforementioned studies, our findings strongly suggest that routine ultrasound screening of hospitalized patients with DVT of the lower extremities, followed by the timely and effective implementation of therapeutic interventions according to the screening results, can effectively prevent the occurrence of FPE and reduce mortality in patients with lower-extremity DVT. The discrepancies between our results and those presented by the aforementioned studies could be due to the reduced number of cases examined in other reports and the fact that the cost of ultrasonography in China is not as high as in other countries.

Following ultrasound screening, the decision to place an IVCF or administer thrombolytic therapy is made based on the patient’s condition, with the aim of preventing FPE. Previous studies have reported that IVCF placement32 and catheter thrombolysis33 can effectively prevent FPE. We placed the IVC filter according to the standards of the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), and the placement of the IVC filters were in three clinical scenarios: (1) in patients with VTE and classic indications; (2) in patients with VTE and extended indications; and (3) in patients does not have VTE, but is at risk of developing DVT and/or PE and cannot receive anticoagulation or be monitored for the development of VTE34,35. However, a study shows that the implantation rate of prophylactic IVC filters may decline over time, while the incidence of FPE remains unchanged after the implantation of IVC filters36. Therefore, this result indicates that the preventive effect of IVC filters on FPE may be limited. Consequently, not all patients in our study opted for the implantation of IVC filters, and only 40 patients underwent the implantation of IVC filters. In our study, 40 patients with proximal thrombosis who underwent IVCF placement survived. Conversely, of the 30 patients with proximal thrombosis who underwent thrombolytic therapy, one developed FPE, thus supporting the preventive efficacy of IVCF placement and catheter thrombolysis. Furthermore, CTPA and active thrombolytic therapy significantly improved the prognosis of patients with PE37. CTPA has excellent sensitivity and accuracy in diagnosing PE, as it can more clearly highlight the embolic site, which is of great significance for formulating appropriate treatment plans.

Surgery is a type of trauma due to the changes it provokes in the coagulation system, thus making surgical patients a high-risk group for thrombosis. Xiaoying et al. showed that previous surgical procedures were independent risk factors for developing PE38. In clinical practice, the incidence and mortality rates of postoperative PE in orthopedic patients are higher than those in general surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, and cardiothoracic surgery14,39. Therefore, orthopedic clinicians should pay more attention to the potential occurrence of postoperative PE in their patients to implement effective therapeutics in a timely manner. But we observed that the incidence rate of FPE in orthopedic surgical patients was significantly lower than in non-surgical patients. This conclusion may stem from the observation that a subset of patients had succumbed to PE prior to undergoing orthopedic surgery. Consequently, we incorporated this group into the non-surgical cohort, ultimately arriving at the contrasting conclusion that orthopedic surgery serves as a protective factor against FPE.

Coronary heart disease is an independent risk factor for FPE. The incidence of coronary heart disease is increasing annually and has become the leading cause of cardiovascular disease-related deaths in North America37. Cate et al. concluded that coronary artery disease is common in patients with PE and is a high-risk factor for the development of embolisms40. Heidinger et al. showed that coronary heart disease is widespread in patients with acute PE. They also reported that coronary heart disease was an independent risk factor for PE and that the mortality rate of patients with PE and severe coronary atherosclerosis was 9.5%41. Therefore, in clinical practice, more attention should be paid to patients with coronary heart disease, who should be continuously monitored to implement effective intervention measures when necessary.

Finally, proximal thrombosis was identified as a high-risk factor for FPE. Previous studies have shown that in the case of venous thrombosis, the incidence of PE is between 52 and 79.4% but could increase to 87.8% if distal thrombosis is included. A previous study reported that between 7.8 and 78.9% of patients with PE will experience FPE and that the incidence in individuals with lower-extremity DVT was higher than that in those with proximal thrombosis1. Therefore, patients with proximal thrombosis should immediately undergo anticoagulation therapy, IVCF placement, or other treatments to prevent fatal PE.

Limitations

This study was a single-center retrospective study; thus, only a few cases of PE and FPE were recorded annually. Future multicenter prospective studies should be conducted to confirm our findings. In our study, indeed a part of the patients were diagnosed with PE only based on clinical symptoms without the imaging examination results such as echocardiogram. We tried to correct this defect, but we found it very difficult because the patient’s condition deteriorated acutely and there was no time window to conduct imaging examinations, and some family members of the patients refused to conduct such examinations. We did not exclude this part of the patients because we believe that excluding these patients would lead to significant bias in our research. In addition, the diagnostic value of ultrasonography in patients with DVT remains controversial; however, it is still the most widely employed diagnostic method in hospitals. Our study did not investigate the effectiveness of venography as a diagnostic criterion, which may have biased our results. Furthermore, the inclusion of patients who had succumbed to PE prior to orthopedic surgery in the non-operative group influenced our conclusion, leading us to surmise that orthopedic surgery acts as a protective factor against such fatalities. Finally, due to rapid deterioration or refusal by the patients and their families, ultrasound results could not be obtained for 31 patients. Therefore, this reduces the reliability of the data.

Conclusion

Perioperative ultrasound screening in orthopedic patients can effectively reduce the incidence of PE and FPE. Prophylactic IVCF placement, thrombolytic therapy, and CTPA can effectively reduce the incidence of FPE, for which coronary heart disease is independent risk factors. Therefore, we recommend routine screening of the lower extremity veins in orthopedic patients using color Doppler ultrasound and prophylactic measures, such as prophylactic IVCF placement and thrombolysis guided by ultrasound, to reduce the incidence of FPE.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sevitt, S. & Gallagher, N. Venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A clinico-pathological study in injured and burned patients. Br. J. Surg. 48, 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.18004821103 (1961).

Shackford, S. R. et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with major trauma. Am. J. Surg. 159, 365–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81272-3 (1990).

Tutar, B., Kantarci, F., Cakmak, O. S., Yazici, H. & Seyahi, E. Assessment of deep venous thrombosis in the lower extremity in Behçet’s syndrome: MR venography versus Doppler ultrasonography. Intern. Emerg. Med. 14, 705–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-019-02040-4 (2019).

de Valois, J. C. et al. Contrast venography: From gold standard to ‘golden backup’ in clinically suspected deep vein thrombosis. Eur. J. Radiol. 11, 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/0720-048x(90)90162-5 (1990).

Fletcher, J. P., Kershaw, L. Z., Barker, D. S., Koutts, J. & Varnava, A. Ultrasound diagnosis of lower limb deep venous thrombosis. Med. J. Aust. 153, 453–455. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1990.tb126149.x (1990).

Fernandez-Canton, G. et al. Diagnostic utility of color Doppler ultrasound in lower limb deep vein thrombosis in patients with clinical suspicion of pulmonary thromboembolism. Eur. J. Radiol. 19, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/0720-048x(94)00569-x (1994).

Gaitini, D. Current approaches and controversial issues in the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis via duplex Doppler ultrasound. J. Clin. Ultrasound 34, 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcu.20236 (2006).

Lagerstedt, C. I., Olsson, C. G., Fagher, B. O., Oqvist, B. W. & Albrechtsson, U. Need for long-term anticoagulant treatment in symptomatic calf-vein thrombosis. Lancet 2, 515–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90459-3 (1985).

Yamaki, T. et al. Presence of lower limb deep vein thrombosis and prognosis in patients with symptomatic pulmonary embolism: Preliminary report. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 37, 225–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.08.018 (2009).

Zhang, C. et al. Relationship between the site of thrombosis and the prevalence of pulmonary embolism in acute lower extremity deep venous thrombosis. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 8, 725–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvsv.2019.11.010 (2020).

Piovella, F. et al. Deep-vein thrombosis rates after major orthopedic surgery in Asia. An epidemiological study based on postoperative screening with centrally adjudicated bilateral venography. J. Thromb. Haemost. 3, 2664–2670. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01621.x (2005).

Nasser, M. F. et al. Echocardiographic evaluation of pulmonary embolism: A review. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 36, 906–912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2023.05.006 (2023).

Loud, P. A., Katz, D. S., Bruce, D. A., Klippenstein, D. L. & Grossman, Z. D. Deep venous thrombosis with suspected pulmonary embolism: Detection with combined CT venography and pulmonary angiography. Radiology 219, 498–502. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.219.2.r01ma26498 (2001).

Guidelines on diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Task force on pulmonary embolism, European society of cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 21, 1301–1336. https://doi.org/10.1053/euhj.2000.2250 (2000).

Goldhaber, S. Z. Pulmonary embolism. Lancet 363, 1295–1305. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(04)16004-2 (2004).

Knudson, M. M., Gomez, D., Haas, B., Cohen, M. J. & Nathens, A. B. Three thousand seven hundred thirty-eight posttraumatic pulmonary emboli: A new look at an old disease. Ann. Surg. 254, 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182300209 (2011).

Velmahos, G. C. et al. Pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis in trauma: Are they related?. Arch. Surg. 144, 928–932. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2009.97 (2009).

Van Gent, J. M. et al. Pulmonary embolism without deep venous thrombosis: De novo or missed deep venous thrombosis?. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 76, 1270–1274. https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0000000000000233 (2014).

Digby, G. C. et al. The value of electrocardiographic abnormalities in the prognosis of pulmonary embolism: A consensus paper. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 20, 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/anec.12278 (2015).

Haut, E. R. et al. Duplex ultrasound screening for deep vein thrombosis in asymptomatic trauma patients: A survey of individual trauma surgeon opinions and current trauma center practices. J. Trauma 70, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3182077d55 (2011).

Geerts, W. H. et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest 133, 381s–453s. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-0656 (2008).

Rogers, F. B., Cipolle, M. D., Velmahos, G., Rozycki, G. & Luchette, F. A. Practice management guidelines for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in trauma patients: The EAST practice management guidelines work group. J. Trauma 53, 142–164. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-200207000-00032 (2002).

Piotrowski, J. J. et al. Is deep vein thrombosis surveillance warranted in high-risk trauma patients?. Am. J. Surg. 172, 210–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9610(96)00154-7 (1996).

Napolitano, L. M. et al. Asymptomatic deep venous thrombosis in the trauma patient: Is an aggressive screening protocol justified?. J. Trauma 39, 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-199510000-00006 (1995).

Burns, G. A., Cohn, S. M., Frumento, R. J., Degutis, L. C. & Hammers, L. Prospective ultrasound evaluation of venous thrombosis in high-risk trauma patients. J. Trauma 35, 405–408. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-199309000-00012 (1993).

Meythaler, J. M., DeVivo, M. J. & Hayne, J. B. Cost-effectiveness of routine screening for proximal deep venous thrombosis in acquired brain injury patients admitted to rehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 77, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90210-5 (1996).

Brasel, K. J., Borgstrom, D. C. & Weigelt, J. A. Cost-effective prevention of pulmonary embolus in high-risk trauma patients. J. Trauma 42, 456–462. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-199703000-00013 (1997).

Cipolle, M. D., Wojcik, R., Seislove, E., Wasser, T. E. & Pasquale, M. D. The role of surveillance duplex scanning in preventing venous thromboembolism in trauma patients. J. Trauma 52, 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-200203000-00007 (2002).

Meyer, C. S., Blebea, J., Davis, K. Jr., Fowl, R. J. & Kempczinski, R. F. Surveillance venous scans for deep venous thrombosis in multiple trauma patients. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 9, 109–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02015324 (1995).

Spain, D. A. et al. Venous thromboembolism in the high-risk trauma patient: Do risks justify aggressive screening and prophylaxis?. J. Trauma 42, 463–469. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-199703000-00014 (1997).

Satiani, B., Falcone, R., Shook, L. & Price, J. Screening for major deep vein thrombosis in seriously injured patients: A prospective study. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 11, 626–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s100169900101 (1997).

Magnowski, A. et al. The law of unintended consequences: Current design challenges in inferior vena cava filters. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 14, 805–810. https://doi.org/10.1080/17434440.2017.1374850 (2017).

Xue, G. H. et al. Catheter-directed thrombolysis and stenting in the treatment of iliac vein compression syndrome with acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis: Outcome and follow-up. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 28, 957–963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avsg.2013.11.012 (2014).

Kaufman, J. A. et al. Guidelines for the use of retrievable and convertible vena cava filters: Report from the society of interventional radiology multidisciplinary consensus conference. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2, 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2006.03.009 (2006).

DeYoung, E. & Minocha, J. Inferior vena cava filters: Guidelines, best practice, and expanding indications. Semin. Intervent. Radiol. 33, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1581088 (2016).

Cook, A. D. et al. Vena cava filter use in trauma and rates of pulmonary embolism, 2003–2015. JAMA Surg. 152, 724–732. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1018 (2017).

Bledsoe, J. R. et al. Electronic pulmonary embolism clinical decision support and effect on yield of computerized tomographic pulmonary angiography: ePE-A pragmatic prospective cohort study. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2, e12488. https://doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12488 (2021).

Chen, X., Liu, X., Liu, J. & Zhang, D. Pulmonary embolism secondary to deep venous thrombosis: A retrospective and observational study for clinical characteristics and risk stratification. Phlebology 36, 627–635. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268355521990964 (2021).

Gafsou, B. & Samama, C. M. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical patients. Rev. Prat. 61, 1221–1228 (2011).

Ten Cate, V. et al. Isolated pulmonary embolism is associated with a high risk of arterial thrombotic disease: Results from the VTEval study. Chest 158, 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.01.055 (2020).

Heidinger, B. H. et al. Risk assessment of acute pulmonary embolism utilizing coronary artery calcifications in patients that have undergone CT pulmonary angiography and transthoracic echocardiography. Eur. Radiol. 31, 2809–2818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-020-07385-5 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank all of our colleagues working in the Department of Orthopaedics and Trauma, Honghui Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University.

Funding

This study was supported by the Social Development Foundation of Shaanxi Province (grant no: 2017ZDXM-SF-009 and 2022SF-394).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of this study. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by H.L., Z.L., N.Y., J.X., H.Y., Z. S., X.W., T.M., and Q.W. P.W. and K.Z. designed the study. The first draft of the manuscript was written by H.L., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Li, Z., Yang, N. et al. Perioperative ultrasound screening of lower extremity veins is effective in the prevention of fatal pulmonary embolism in orthopedic patients. Sci Rep 15, 229 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84572-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84572-0