Abstract

Hydroxytyrosol, a fine chemical, is widely utilized in food and pharmaceutical industries. In this study, we constructed a pathway to produce hydroxytyrosol by co-expressing tyrosin-phenol lyase (TPL), L-amino acid dehydrogenase (aadL), α-keto acid decarboxylase (KAD), aldehyde reductase (yahK) and glucose dehydrogenase (gdh). We changed combinations between plasmids with different copy numbers and target genes, resulting in 84% increase in hydroxytyrosol production. The yield of hydroxytyrosol was further increased 89.3% by optimizing the temperature and pH. Finally, 55.3 mM hydroxytyrosol was produced within 14 h by fed-batch biotransformation. This study provides a novel approach for hydroxytyrosol production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydroxytyrosol is a potent antioxidant and mainly distributed in olive leaves and fruits. Hydroxytyrosol has a variety of effects in preventing diseases and improving human health, such as anti-proliferative, lipid regulation, anti-inflammatory and prevention of cardiovascular diseases1,2,3,4,5.

Hydroxytyrosol can be obtained through the extraction of wastewater generated during the production of olive oil and is up to 98% in the waste water6. Extracting hydroxytyrosol from olive oil wastewater has many defects, mainly facing the difficulty of extraction, high cost and the complex extraction process. Hydroxytyrosol can be produced from catechol by chemical process7. However, chemical production of hydroxytyrosol has some disadvantages, such as high production cost, use of heavy metal ions that pollute the environment and harsh reaction conditions. Hydroxytyrosol can also be produced by photocatalysis8. However, photocatalysis has not been widely used in industrial production due to low conversion rate and concentration of the final product. At present, multienzyme cascade reactions have been employed for the synthesis of many compounds due to the mild reaction conditions, strong catalytic specificity and high efficiency9. Biotechnology shows great industrial application prospect with the enhancement of environmental protection awareness.

Many research groups have developed numerous biological methods for production of hydroxytyrosol. Metabolic engineering is an effective method to produce hydroxytyrosol. Li et al. proposed a method to produce hydroxytyrosol by co-expressing ketoacid decarboxylase, alcohol dehydrogenase, HpaB/HpaC and transamination. Assembly of the full pathway resulted in 0.64 g/L hydroxytyrosol10. Liu et al. optimized the biosynthesis of hydroxytyrosol by screening effective HpaB/HpaC combinations, biosynthesis flux recombination and cofactor engineering. Finally, the engineered strain produced 6.97 g/L hydroxytyrosol11. Wang et al. achieved the biosynthesis of hydroxytyrosol by introducing HpaB/HpaC from Escherichia coli and ARO10 and ADH6 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. After the optimization of carbon source, pH and seed medium, the optimal engineered strain produced 9.87 g/L hydroxytyrosol12.

To simplify the production steps and increase the yield of hydroxytyrosol, whole cell catalysis method has been widely developed. Pinero et al. built engineered strains using hydroxylase to convert tyrosol into hydroxytyrosol13. Wijata et al. reported a method for converting 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid to hydroxyltyrosol by overexpressing carboxylic acid reductase, phosphopantetheinyl transferase and aldehyde reductase14. Chen et al. established a method to produce hydroxytyrosol with tyrosine as substrate. To increase the yield of hydroxytyrosol, the catalytic activity of HpaB was improved through high-throughput screening. Finally, the yield of hydroxytyrosol was 5.6 mM within 36 h with a conversion yield of 93 mol%15. Yao et al. then increased tyramine oxidase activity by using in vivo-directed evolution. Finally, the yield of hydroxytyrosol was 13.5 mM within 36 h with a conversion yield of 95 mol%16. Li et al. constructed an engineered strain, which transformed L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) to hydroxytyrosol. After optimizing the transformation conditions, the yield of hydroxytyrosol reached 36.3 mM within 10 h with a conversion yield of 89.4 mol%17. These methods are inefficient in producing hydroxytyrosol or the selected substrate is expensive. Therefore, there is still a need to develop more economical and efficient methods for production of hydroxytyrosol.

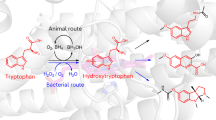

In the present study, we constructed engineered strains for production of hydroxytyrosol by introducing heterologous genes, including tyrosin-phenol lyase (TPL), amino acid dehydrogenase (aadL), α-keto acid decarboxylase (KAD), aldehyde reductase (yahK) and glucose dehydrogenase (gdh) (Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

Pathway and plasmid construction

The codon-optimized genes of glucose dehydrogenase (gdh) and L-amino acid deaminase (aadL) were obtained from previous studies18. Tyrosin-phenol lyase (TPL) (GenBank ID: AAL94078) was amplified from the genome of Fusobacterium nucleatum ATCC2558619. α-keto acid decarboxylase (KAD) (GenBank ID: KY441412) was amplified from the genome of Proteus mirabilis JN45820. Aldehyde reductase (yahK) (GenBank ID: AAC73428) was amplified from the genome of E. coli BL21 (DE3)21.

All constructed plasmids were sequenced by Tianlin (Wuxi, China). All primers used for constructing plasmids are listed in Table S1. The plasmids and recombinant strains are listed in Table S2. The KAD was amplified from Proteus mirabilis JN458 using KAD-BamHI (F) and KAD-SacI (R) and cloned into pRSFDuet-1 between BamHI and SacI, the successfully constructed plasmid was named pRSF-KAD. The yahK, TPL and aadL was amplified using yahK-KpnI (F) and yahK-XhoI (R), TPL-KpnI (F) and TPL-XhoI (R), aadL-KpnI (F) and aadL-XhoI (R). All fragments were cloned into pRSF-KAD between KpnI and XhoI, the successfully constructed plasmids were named pRSF-KAD-yahK, pRSF-KAD-TPL and pRSF-KAD-aadL, respectively. Furthermore, yahK was amplified using yahK-SacI (F) and yahK-NotI (R). The fragments were cloned into pRSF-KAD-TPL and pRSF-KAD-aadL between SacI and NotI, respectively. The successfully constructed plasmids were named pRSF-KAD-yahK-TPL and pRSF-KAD-yahK-aadL, respectively.

Additionally, TPL, yahK and aadL was amplified using TPL-BamHI (F) and TPL-SacI (R), yahK-BamHI (F) and yahK-SacI (R), aadL-BamHI (F) and aadL-SacI (R). The fragments were cloned into pETDuet-1 between BamHI and SacI. The successfully constructed plasmids were named pET-TPL, pET-yahK and pET-aadL, respectively. The aadL was amplified using aadL-KpnI (F) and aadL-XhoI (R). The fragments were cloned into pET-TPL and pET-yahK between KpnI and XhoI, respectively. The successfully constructed plasmids were named pET-TPL-aadL and pET-yahK-aadL, respectively. The yahK was amplified using yahK-KpnI (F) and yahK-XhoI (R). The fragments were cloned into pET-TPL between KpnI and XhoI. The successfully constructed plasmid was named pET-TPL-yahK. The gdh was amplified using gdh-KpnI (F) and gdh-XhoI (R). The fragments were cloned into pET-aadL and pET-TPL between KpnI and XhoI, respectively. The successfully constructed plasmids were named pET-aadL-gdh and pET-TPL-gdh, respectively. The gdh was amplified using gdh-BamHI (F) and gdh-SacI (R). The fragments were cloned into pCDFDuet-1 and pACYCDuet-1 between BamHI and SacI, respectively. The successfully constructed plasmids were named pCDF-gdh and pACYC-gdh, respectively. The TPL was amplified using TPL-KpnI (F) and TPL-XhoI (R). The fragments were cloned into pCDF-gdh between KpnI and XhoI. The successfully constructed plasmid was named pCDF-TPL-gdh.

The resulting plasmids were transformed into E.coli BL21(DE3), the following strains were successfully constructed: strain 1 (pRSF-KAD-yahK/pET-TPL-aadL/pCDF-gdh), strain 2 (pRSF-KAD-TPL/pET-yahK-aadL/pCDF-gdh), strain 3 (pRSF-KAD-aadL/pET-TPL-yahK/pCDF-gdh), strain 4 (pRSF-KAD-aadL/pET-TPL-yahK/pACYC-gdh), strain 5 (pRSF-KAD-aadL/pET-TPL-yahK-gdh), strain 6 (pRSF-KAD-aadL-TPL/pET-yahK-gdh), strain 7 (pRSF-KAD-aadL-yahK/pET-TPL-gdh) and strain 8 (pRSF-KAD-aadL-yahK/pCDF-TPL-gdh).

Culture of Escherichia coli and preparation of cell extracts

The recombinant Escherichia coli was inoculated into 3 mL terrific broth (TB) medium at a volume fraction of 0.1% and incubated at 37 °C, 220 rpm, 12 h. Subsequently, the inoculum was transferred to fresh 50 mL TB medium at a volume fraction of 1%, and the culture was further incubated at 37 °C, 220 rpm until the OD600 reached 0.5, and then isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to achieve a final concentration of 0.4 mM. The strain was cultured at 20 °C, 220 rpm, 24 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (4 °C, 8000 g) and washed twice with phosphate buffer (50mM). Then phosphate buffer was added to resuspend the cells until the OD600 reached 30. The ultrasonic fragmentation was used to lyse cells. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (4 °C, 8000 g, 2 min) and the supernatant containing the crude enzyme was collected.

Enzyme activity test

To determine the activity of TPL, the reaction mixture (50 mL) based on 1 mL TPL, 10 mL aadL, 10 mL KAD, 10 mL yahK, 10 mM NADH, 10 mM catechol, 10 mM pyruvic acid, 10 mM ammonium chloride. To determine the activity of aadL, the reaction mixture (50 mL) based on 1 mL aadL, 10 mL KAD, 10 mL yahK, 10 mM NADH, 10 mM L-DOPA. To determine the activity of KAD, the reaction mixture (50 mL) based on 10 mL yahK, 10 mM NADH, 10 mM DOPP. To determine the activity of yahK, the reaction mixture (50 mL) based on 10 mM NADH, 10 mM 3,4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde. The concentration of hydroxytyrosol was detected by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). To determine the activity of gdh, the reaction mixture (50 mL) based on 10 mM NAD+, 10 mM glucose and NADH was detected at 340 nm. Increase of 1 µmol hydroxytyrosol (NADH)/min was 1 unit of total enzyme activity. The results were converted into enzyme activity units contained in 1 mL whole cell catalyst.

Whole-cell biotransformation for hydroxytyrosol production

Strains were washed with phosphate buffer and resuspended in an equivalent volume of phosphate buffer. Reaction system consisted of 50 g/L wet cells, 40 mM catechol, 60 mM pyruvic acid and 60 mM ammonium chloride. The reaction condition was 35 ℃, pH 7.5, and the reaction was allowed to proceed for 12 h at 150 rpm. After the reaction, the mixture was boiled (2 min) to inactivate the enzyme, and then centrifuged (8000 g, 2 min) to remove the bacterial cells. The concentration of various compounds in the reaction solution were determined by HPLC.

Optimization of pH and temperature

Strain 4 was inoculated into flask with TB medium. The flask was filled with 20 mL reaction system and the reaction time was 1 h. Reaction system comprised 50 g/L wet cells, 40 mM catechol, 60 mM pyruvic acid, 60 mM glucose and 60 mM ammonium chloride. To optimize pH, the temperature and shaker speed were 37 °C and 150 rpm. The pH levels were adjusted to 5.5, 6, 6.5, 7, 7.5, 8, 8.5 using phosphate buffer and Tris-HCL buffer. To optimize temperature, the pH and shaker speed were 7.5 and 150 rpm. The temperature was varied to 15 °C, 20 °C, 25 °C, 30 °C, 35 °C and 40 °C, respectively.

Large-scale culture of recombinant Escherichia coli in 5 L bioreactor

Strain 4 was inoculated into flask with TB medium. The culture condition was 37 °C, 220 rpm for 12 h. Following this, 50 mL seed solution was inoculated into 3 L TB medium. The temperature was adjusted to 37 °C, the initial ventilation was adjusted to 5 L/min, and the dissolved oxygen level was maintained at 20% by controlling the stirring speed of 100–500 rpm. The pH of culture medium was adjusted by sodium hydroxide and hydrogen chloride. When the OD600 reached 15, 0.4 mM IPTG (final concentration) was added into 3 L TB medium, and the culture temperature was adjusted to 25 °C. The wet cells were obtained by centrifugation (4 °C, 8000 g, 5 min).

Scaled-up production of hydroxytyrosol in 5 L bioreactor

The biotransformation system was 1.5 L and consisted of 50 g/L wet cells, 60 mM glucose, 60 mM ammonium chloride, 60 mM pyruvic acid and 40 mM catechol. The temperature and pH were maintained at 25 °C and 7.5, respectively. The pH was adjusted by adding sodium hydroxide and hydrogen chloride. The speed of air supplied was 1 L/min, and the dissolved oxygen level was regulated at 3% by modulating the stirring speed of 100–500 rpm. In the process of transformation, feeding methods were divided into feeding every 8 h, feeding every 4 h, feeding every 2 h and no feeding. After each feeding, the content of catechol reached 40 mM. Samples were taken every 2 h and centrifuged at 4 °C, 8000 g for 5 min. The supernatant was diluted and filtered by microporous membrane, and then the content of various substances was determined by HPLC.

Analytical methods

The concentrations of products and substrates were detected by HPLC (Shimadzu). GALAK column was used to separate the substances in the sample, and the injection volume of each sample was 10 µL. The temperature of column was maintained at 35 °C. Gradient elution was used after injection. The eluting mobile phase was methanol and water containing 0.1% formic acid. The elution procedure was set as follows: 0–15 min, 10% methanol was increased to 100% methanol; 15–20 min, the column was washed with 100% methanol; 20–30 min, the column was balanced with 10% methanol. The detection wavelength of the system is 280 nm.

Results

Construction of hydroxytyrosol synthesis pathway

To construct strain 1, we utilized pCDFDuet-1, pETDuet-1 and pRSFDuet-1 to express TPL, aadL, KAD, yahK and gdh (Fig. 2). The pRSFDuet-1 (high copy number plasmid) was used to express KAD and aadL, pETDuet-1 (medium copy number plasmid) was used to express TPL and yahK, and pCDFDuet-1 (low copy number plasmid) was used to express gdh. After the conversion, 9.32 mM hydroxytyrosol was produced. To verify the production of hydroxytyrosol, the products were detected by HPLC (Fig. 3) and UPLC-MS (Fig.S1). The peak time, mass-to-charge ratio and UV absorption spectra is the same as that of hydroxytyrosol standard.

Combination of different copy number plasmids to improve production of hydroxytyrosol

Previous studies have shown that changing combinations between plasmids with different copy numbers and target genes can improve the production capacity of engineered strains22,23. We used plasmids with different copy numbers to express pathway genes (Fig. 2A). These plasmids encompassed PACYCDuet-1, pCDFDuet-1, pETDuet-1 and pRSFDuet-1. The expression levels of transcription for the five genes within the eight engineered strains of E. coli were individually measured through reverse transcriptase-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), and the illustration of their relative transcript abundances is provided in Figure S2. The recombinant E. coli strains was used to produce hydroxytyrosol and the reaction time was 5 h (Fig. 2B).

When strain 2 (pRSF-KAD-TPL, pET-yahK-aadL, pCDF-gdh) and strain 1 (pRSF-KAD-yahK, pET-TPL-aadL, pCDF-gdh) were compared, TPL in strain 2 was expressed by high copy plasmid of pRSFDuet-1. TPL in strain 1 was expressed using a medium intensity plasmid of pETDuet-1, and the activity of TPL was higher in strain 2 (5.52 U/mL) than in strain 1 (3.12 U/mL) (Fig. 2C). The TPL relative transcription level of strain 2 is also higher than that of strain 1 (Fig. S2). HPLC analysis showed that the hydroxytyrosol production of strain 2 (8.24 mM) was slightly lower than that of strain 1 (9.32 mM) (Fig. 2B). To study the effect of aadL on the production of hydroxytyrosol, strain 3 (pRSF-KAD-aadL, pET-TPL-yahK, pCDF-gdh) was constructed. KAD and aadL in strain 3 were expressed by high copy plasmid of pRSFDuet-1. TPL and yahK were expressed by medium copy plasmid of pETDuet-1. The aadL relative transcription level of strain 3 is higher than that of strain 1 (Fig. S2). HPLC analysis showed that the yield of hydroxytyrosol in strain 3 (15.86 mM) increased sharply compared with strain 1 (23.3%) and strain 2 (20.6%). It can be concluded that strong overexpression of aadL is essential for the synthesis of hydroxytyrosol. When strain 4 (pRSF-KAD-aadL, pET-TPL-yahK, pACYC-gdh) was compared with strain 3, the gdh in strain 4 was expressed by the ultra-low copy plasmid of pACYCDuet-1. HPLC analysis showed that the yield of hydroxytyrosol in strain 4 (43.08%) was higher than that in strain 3 (39.65%).

Then we constructed strain 5 (pRSF-KAD-aadL, pET-TPL-yahK-gdh). KAD and aadL in strain 5 were expressed by high copy plasmid of pRSFDuet-1. TPL, yahK and gdh were expressed by medium copy plasmid of pETDuet-1. The strain 6 (pRSF-KAD-aadL-TPL, pET-yahK-gdh) was also constructed. KAD, aadL and TPL in strain 6 were expressed by high copy plasmid of pRSFDuet-1, yahK and gdh were expressed by medium copy plasmid of pETDuet-1. When strain 4 and strain 5 were compared, gdh in strain 5 was expressed by medium intensity plasmid, and the activity of gdh was significantly enhanced in strain 5 (6.73 U/mL) than in strain 1 (3.75 U/mL) (Fig. 2C). HPLC analysis showed that the yield of hydroxytyrosol of strain 5 (41.23%) was slightly decreased compared with strain 4 (43.08%). In addition, HPLC analysis showed that the yield of hydroxytyrosol of strain 6 (38.73%) was lower than that of strain 5 (41.23%). Then strain 7 (pRSF-KAD-aadL-yahK, pET-TPL-gdh) was constructed. KAD, aadL and yahK in strain 7 were expressed by high copy plasmid of pRSFDuet-1, TPL and gdh were expressed by low copy plasmid of pCDFDuet-1. HPLC analysis showed that the yield of hydroxytyrosol of strain 7 (28.93%) was significantly lower than that of strain 6 (38.73%). Finally, strain 8 (pRSF-KAD-aadL-yahK, pCDF-TPL-gdh) was constructed. KAD, aadL and yahK in strain 8 were expressed by high copy plasmid of pRSFDuet-1, TPL and gdh were expressed by low copy plasmid of pCDFDuet-1. The results of HPLC analysis showed that the yield of hydroxytyrosol of strain 8 (37.15%) was higher than that of strain 7 (28.93%). Overall, strain 4 (17.23 mM) was able to produce the highest amount of hydroxytyrosol relative to other strains. The hydroxytyrosol yield of strain 4 (43.08%) increased by 84% compared with that of strain 1 (23.3%).

Optimization of pH and temperature

Culture conditions are crucial for whole cell biotransformation. For pH optimization, hydroxytyrosol gradually increased when the pH was from 5.5 to 7.5. Conversely, the production of hydroxytyrosol decreased gradually at pH ranging from 7.5 to 8.5. The optimum pH was 7.5 (Fig. 4A). For temperature optimization, hydroxytyrosol gradually increased when the temperature was from 15 °C to 25 °C. The production of hydroxytyrosol decreased gradually at temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 40 °C. The optimum reaction temperature was 25 °C, yielding 17.38 mM hydroxytyrosol (Fig. 4B).

Scaled-up production of hydroxytyrosol using fed-batch biotransformation

Previous studies have shown that high concentrations of catechol can inhibit enzyme activity and reduce the yield of production19. To increase the yield of hydroxytyrosol, the fed-batch biotransformation was performed by feeding catechol, pyruvate and ammonium chloride in 5 L bioreactor.

The initial concentration of catechol was added by 40 mM. Without feeding, the total amount of catechol was added by 40 mM. The yield of hydroxytyrosol was 30.8 mM within 14 h (Fig. 5A). When feeding every 2 h, the total amount of catechol was added by 88.6 mM. The yield of hydroxytyrosol was 55.3 mM within 14 h (Fig. 5B). When feeding every 4 h, the total amount of catechol was added by 80.5 mM. The yield of hydroxytyrosol was 42.2 mM within 14 h (Fig. 5C). When feeding every 8 h, the total amount of catechol was added by 66.3 mM. The yield of hydroxytyrosol was 34.9 mM within 14 h (Fig. 5D). The maximum yield of hydroxytyrosol was obtained by feeding every 2 h. The hydroxytyrosol yield of feeding every 2 h is 1.8 times that of no feeding.

Discussion

Cascade reactions play an important role in synthetic chemical products and can avoid waste formation, time consumption and expensive purification operations. With the rapid development of bioinformatics and protein engineering, whole cell biotransformation has been widely used in the production of various foods, drugs and daily necessities and has achieved huge economic and social benefits9.

Hydroxytyrosol is a valuable bioactive compound. Many biosynthetic methods of hydroxytyrosol have been reported in the past. Hydroxytyrosol could be produced at 1.3 mM, 1.7 mM, 8.1 mM and 12.3 mM with tyrosine as substrate10,15,24,25. 10.4 mM, 16 mM and 24.9 mM hydroxytyrosol could be produced using tyrosol as substrate26,27,28. The productivity of hydroxytyrosol is low using tyrosine and tyrosol as substrates due to the low activity of hydroxylase, which is difficult to meet the requirements of industrial production. L-DOPA can also be used as a substrate to synthesize hydroxytyrosol by recombinant Escherichia coli17. However, L-DOPA is more expensive and high pH will cause the decomposition of L-DOPA, resulting in the loss of L-DOPA29. Thus, a cascade for transformation of catechol and pyruvate to hydroxytyrosol is desired. Recently, zhao et al. envisions a cascade biocatalytic approach to convert lignin-derived catecholins and phenols into hydroxytyrosol by integrating C-C coupling, hydroxylation, decarboxylation, deamination, and reduction. The maximum titers of 20.6 mM (3.18 g/L) and 18.5 mM (2.85 g/L) were obtained from 30 mM catechol and phenol by batch feeding of recombinant Escherichia coli resting cells30. In this study, the yield of hydroxytyrosol was significantly higher than in previous studies, 55.3 mM hydroxytyrosol was efficiently produced by fed-batch biotransformation using catechol and pyruvate as substrates.

The balance of various combination enzymes is important in whole cell biotransformation. Previous studies have shown that different copy numbers plasmids can balance the expression of enzymes31,32. In this study, we used different copy numbers plasmids to express target genes. The results showed that strain 4, which was constructed with high copy plasmids that strongly overexpressed KAD and aadL, medium copy plasmids that moderately overexpressed TPL and yahK, and low copy plasmids that weakly expressed gdh, could produce the highest yield of hydroxytyrosol. The weak expression of gdh can meet the requirement of NADH regeneration due to the high activity33. During the fed-batch biotransformation, higher conversion efficiencies were observed when catechol was maintained at approximately 30 mM. This may be attributed to the existence of a narrow optimal concentration window for catechol, where higher conversion efficiencies can be achieved when the catechol concentration is maintained within a certain range.

Conclusions

In this study, catechol, sodium pyruvate and ammonium chloride were utilized as substrates to produce hydroxytyrosol. The expression of pathway genes was regulated through different copy numbers plasmid which enhanced the production capacity of hydroxytyrosol. Furthermore, the yield of hydroxytyrosol was increased by implementing a batch feeding method. This study has a strong industrial application prospect.

Data availability

All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

References

Wani, T. A. et al. Olive oil and its principal bioactive compound: Hydroxytyrosol – a review of the recent literature. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 77, 77–90 (2018).

Aghaei, E., Soltanzadeh, H., Kohan, L. & Heiat, M. Anti-proliferative effects of hydroxytyrosol against breast cancer cell lines through induction of apoptosis. Gene Cell. Tissue 10 (2022).

Dong, Y. Z., Li, L., Espe, M., Lu, K. L. & Rahimnejad, S. Hydroxytyrosol attenuates hepatic fat accumulation via activating mitochondrial biogenesis and autophagy through the AMPK pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 9377–9386 (2020).

Franceschelli, S. et al. Hydroxytyrosol reduces foam cell formation and endothelial inflammation regulating the PPARγ/LXRα/ABCA1 pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (2023).

Noguera-Navarro, C., Montoro-García, S. & Orenes-Piñero, E. Hydroxytyrosol: Its role in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Heliyon 9 (2023).

Terholsen, H. et al. Recovery of hydroxytyrosol from olive mill wastewater using the promiscuous hydrolase/acyltransferase PestE. Chembiochem 23 (2022).

Ziosi, P. et al. A two-step process for the synthesis of hydroxytyrosol. Chemsuschem 11, 2202–2210 (2018).

Khlifi, H. et al. Photocatalytic partial oxidation of tyrosol: improving the selectivity towards hydroxytyrosol by surface fluorination of TiO2. Top. Catal. 63, 1350–1360 (2020).

Rosenthal, K., Bornscheuer, U. T. & Lutz, S. Cascades of evolved enzymes for the synthesis of complex molecules. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., e202208358 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Establishing an artificial pathway for efficient biosynthesis of hydroxytyrosol. ACS Synth. Biol. 7, 647–654 (2018).

Liu, H. et al. High-level production of hydroxytyrosol in engineered saccharomyces cerevisiae. ACS Synth. Biol. 11, 3706–3713 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Promoting FADH2 regeneration of hydroxylation for high-level production of hydroxytyrosol from glycerol in Escherichia coli. J. Agr Food Chem. 71, 16681–16690 (2023).

Orenes-Piñero, E., García-Carmona, F. & Sánchez-Ferrer, Á. A new process for obtaining hydroxytyrosol using transformed Escherichia coli whole cells with phenol hydroxylase gene from Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius. Food Chem. 139, 377–383 (2013).

Napora-Wijata, K., Robins, K., Osorio-Lozada, A. & Winkler, M. Whole-cell carboxylate reduction for the synthesis of 3-Hydroxytyrosol. Chemcatchem 6, 1089–1095 (2014).

Chen, W. et al. Promiscuous enzymatic activity-aided multiple-pathway network design for metabolic flux rearrangement in hydroxytyrosol biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 10, 960 (2019).

Yao, J. et al. Developing a highly efficient hydroxytyrosol whole-cell catalyst by de-bottlenecking rate-limiting steps. Nat. Commun. 11, 1515 (2020).

Li, C. et al. Efficient synthesis of hydroxytyrosol from L-3,4-Dihydroxyphenylalanine using engineered Escherichia coli whole cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 6867–6873 (2019).

Xiong, T. et al. Biosynthesis of D-danshensu from L-DOPA using engineered Escherichia coli whole cells. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 103 (15), 6097–6105 (2019).

Zheng, R. C. et al. Biochemical characterization of a novel tyrosine phenol-lyase from Fusobacterium nucleatum for highly efficient biosynthesis of L-DOPA. Enzyme Microb. Tech. 112, 88–93 (2018).

Wang, B., Bai, Y., Fan, T., Zheng, X. & Cai, Y. Characterisation of a thiamine diphosphate-dependent alpha-keto acid decarboxylase from proteus mirabilis JN458. Food Chem. 232, 19–24 (2017).

Koma, D., Yamanaka, H., Moriyoshi, K., Ohmoto, T. & Sakai, K. Production of aromatic compounds by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli with an expanded shikimate pathway. Appl. Environ. Microb. 78, 6203–6216 (2012).

Hu, B. et al. Whole-cell P450 biocatalysis using engineered Escherichia coli with fine-tuned heme biosynthesis. Adv. Sci., e2205580 (2022).

Jung, D. Y., Li, X. & Li, Z. Engineering of hydroxymandelate oxidase and cascade reactions for high-yielding conversion of racemic mandelic acids to phenylglyoxylic acids and (R)- and (S)-phenylglycines. ACS Catal. 13, 1522–1532 (2023).

Chung, D., Kim, S. Y. & Ahn, J. H. Production of three phenylethanoids, tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, and salidroside, using plant genes expressing in Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 7, (2017).

Choo, H. J. et al. Microbial synthesis of hydroxytyrosol and hydroxysalidroside. Appl. Biol. Chem. 61, 295–301 (2018).

Allouche, N. & Sayadi, S. Synthesis of hydroxytyrosol, 2-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, and 3-hydroxyphenylacetic acid by differential conversion of tyrosol isomers using Serratia marcescens strain. J. Agr Food Chem. 53, 6525–6530 (2005).

Espin, J. C., Soler-Rivas, C., Cantos, E., Tomas-Barberan, F. A. & Wichers, H. J. Synthesis of the antioxidant hydroxytyrosol using tyrosinase as biocatalyst. J. Agr Food Chem. 49, 1187–1193 (2001).

Allouche, N., Damak, A., Ellouz, R. & Sayadi, S. Use of whole cells of pseudomonas aeruginosa for synthesis of the antioxidant hydroxytyrosol via conversion of tyrosol. Appl. Environ. Microb. 70, 2105–2109 (2004).

Luna-Velasco, A., Field, J. A., Cobo-Curiel, A. & Sierra-Alvarez, R. Inorganic nanoparticles enhance the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) during the autoxidation of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-dopa). Chemosphere 85, 19–25 (2011).

Zhao, R. Y., Huang, S. P., Gao, L. L. & Zhang, J. D. One-pot biocatalytic upgrading of lignin-derived phenol and catechol to hydroxytyrosol. Green. Chem. 26, 6180–6189 (2024).

Xiong, T. et al. Redox self-sufficient biocatalyst system for conversion of 3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl-L-alanine into (R)- or (S)-3,4-Dihydroxyphenyllactic acid. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol., (2019).

You, Z. N. et al. Design of a self-sufficient hydride-shuttling cascade for concurrent bioproduction of 7,12-dioxolithocholate and L-tert-leucine. Green. Chem., (2021).

Zhang, J., Li, A., Yu, H., Imanaka, T. & Xu, J. H. Synthesis of optically pure S-sulfoxide by Escherichia coli transformant cells coexpressing the P450 monooxygenase and glucose dehydrogenase genes. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 38, 633–641 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by Key scientific research project of higher education institutions in Henan Province (24B180017), Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX19_1841) and Nanhu Scholars Program for Young Scholars of XYNU.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.T.Z. designed and initiated the experiments. Y.H.D.; L.J.L.; B.D.Y. and L.X.M. conducted experiments. L.X.M., L.W. and F.G.Y.; Formal analysis; X.T.Z. and L.W. wrote manuscripts. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, T., Li, X., Liu, W. et al. Multienzyme cascade for synthesis of hydroxytyrosol via engineered Escherichia coli. Sci Rep 15, 471 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84624-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84624-5