Abstract

This study investigates the effects of lead stress on tomato plants and explores the potential role of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) to alleviate this stress. The experiment was conducted in pots, introducing varying lead levels (0, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 mg kg⁻¹) using lead nitrate. For rhizobacterial inoculation, pre-characterized LTPGP strains S5 Pseudomonas fluorescens A506 and S10 Pseudomonas fluorescens LMG 2189 were used. Data were recorded on growth parameters (shoot and root length, fresh and dry weight), physiological attributes (chlorophyll content, proline content, electrolyte leakage, and lead accumulation), and antioxidant activities (catalase, peroxidase, superoxide dismutase) in tomato plants. Results revealed that lead contamination significantly impaired plant growth, reducing shoot and root lengths by approximately 49.78–57.62%, and negatively impacted physiological attributes and antioxidant enzyme activities. However, inoculation with PGPR strains S5 and S10 led to notable improvements in growth parameters, enhanced physiological traits, and better antioxidant activities, effectively mitigating lead stress. These findings highlights the potential of PGPR to improve tomato plant resilience to lead contamination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) is a globally cultivated summer vegetable known for its exceptional nutritional value. It provides essential minerals, dietary fibers, vitamins A, B, and C, iron, phosphorus, sugars, essential amino acids, and antioxidants1,2. Additionally, tomato consumption has been associated with a healthy diet, possessing anticancer properties, and increased hematocrit, red blood cell, and white blood cell content2. However, tomato cultivation faces significant challenges due to heavy metal contamination, particularly from lead. This contamination is a serious risk to agriculture and the environment, exacerbated by rapid urbanization and industrialization3,4. Lead pollution in soil primarily stems from the weathering of lead-containing rocks, excessive use of leaded gasoline, sewage water irrigation, and improper waste disposal5,6.

The issue is particularly severe in Pakistan, where soils are frequently contaminated with lead nitrate. According to the WHO, lead levels in several areas of Pakistan exceed permissible limits, with the maximum allowable concentration being 300 mg kg−1 in soil and 0.3 mg kg−1 in vegetation7. High levels of lead in plant tissues disrupt enzyme activities, affect membrane permeability, and impede mineral uptake, leading to oxidative damage through the excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)8,9. Furthermore, lead exposure negatively impacts plants growth by stunting root and stem elongation, hindering photosynthesis and reducing leaf expansion10. It also decreases leaf count, shoot height, flower production, and overall plant height11. Lead primarily accumulates in roots in an insoluble form, limiting its transport to shoots. Nevertheless, photosynthesis is notably affected by lead exposure, significantly reducing chlorophyll content, photosynthetic rate, and CO₂ assimilation3. Lead exposure also decreases the levels of Ca, Fe, and Zn in root tips and inhibits the uptake of K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Fe3+, and Na+12.

In response to the challenges posed by heavy metal contamination, strategies to mitigate metal toxicity and protect crop productivity and environmental health have gained significant interest. Existing research has explored various physical, chemical and biological strategies to address metal toxicity. For instance, physical methods such as soil washing and phytostabilization offer immediate but often temporary solutions, typically requiring specialized equipment and high-energy input13. Chemical approaches, such as the use of chelating agents, can enhance lead mobility and uptake by plants; however, they may pose environmental risks due to residual toxicity14. Among biological methods, phytoremediation and bioremediation are prominent. These strategies rely on plants and microorganisms to either stabilize or remove lead from contaminated soils, although they are generally slower processes15,16. Consequently integrated strategies that combine phytoremediation with bioremediation agents particularly metal-tolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), have gained prominence17,18. PGPR mitigates metal stress through both direct mechanisms, such as nutrient solubilization, phytohormone production, and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase activity, as well as indirect mechanisms like biofilm formation, metal sequestration, and siderophore production, collectively reducing metal toxicity and promoting plant growth32,35.

This study focuses on specific PGPR strains, Pseudomonas fluorescens A506 (S5) and Pseudomonas fluorescens LMG 2189 (S10), chosen for their demonstrated ability to enhance lead tolerance and support plant growth under lead stress19. While these strains were naturally isolated from contaminated soils and have shown promising results in other crops and environments, research on their effectiveness in tomatoes under lead stress is limited. By examining their impact on tomato growth, physiology, antioxidant activities, and lead uptake in a lead-contaminated growth medium, this study aims to provide insights into their utility as a sustainable bioremediation tool. The findings will contribute to understanding the broader implications of PGPR-based remediation and evaluate whether tomatoes cultivated in lead-polluted soils with PGPR support are safe for human consumption.

Materials and methods

Isolation and preparation of PGPR strains

Two Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) strains, S5 Pseudomonas fluorescens A506 (Accession No. CP003041.1) and S10 Pseudomonas fluorescens LMG 2189 (Accession No. GU198103.1), were isolated and prepared in the Soil Microbiology and Biochemistry Laboratory at the Institute of Soil and Environmental Sciences, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan. For inoculum preparation, each strain was cultured in 250 mL conical flasks containing 100 mL of Luria-Bertani broth and incubated at 28 ± 2oC in an orbital shaking incubator at 100 rpm for three days. The cultures were adjusted to an optical density of 0.5 at 535 nm, corresponding to a concentration of 108–109 CFU mL− 1.

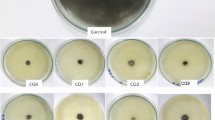

Experimental design and lead contamination

The experiment was conducted in a greenhouse using pots, lead contamination was introduced by adding lead nitrate (Pb(NO3)2) to achieve six distinct concentrations in the sand: 0.00, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 mg kg− 1. After contamination, the growing medium was allowed to stabilize for one week. Before planting, seeds of the tomato cultivar ‘Sandal’ were disinfected with 70% ethanol for three minutes and then washed with distilled water20. One 25-day-old tomato plant was transplanted into each pot (Fig. 1). The experimental design followed a completely randomized design with factorial arrangements. Each treatment combination varied by lead concentration and the presence or absence of inoculation with lead-tolerant rhizobacteria. Treatments were randomly assigned to the pots to minimize bias. To ensure robustness and reliability, four replicates were prepared for each treatment combination, resulting in a total of 72 pots (6 lead levels × 2 rhizobacteria treatments + 1 no bacterial inoculation × 4 replicates). Plants were cultivated under greenhouse conditions, with adequate temperature, light, and humidity. Regular irrigation was maintained throughout the experiment to support optimal growth. Plant growth parameters were measured 100 days after transplanting.

Plant growth parameters

Shoot and root length

The shoot length was measured from the base of the plant at the soil level to the tip of the longest shoot. This measurement was taken using a measuring tape, ensuring accuracy to the nearest millimeter. While for the root length the plants were carefully uprooted to avoid damage to the root system. Excess soil was gently washed off with water. The root length was then measured from the base of the stem to the tip of the longest root using a measuring tape.

Shoot and root weight (Fresh and Dry)

To measure the shoot and root fresh and dry weight, tomato plants were carefully uprooted, and excess soil was washed off the roots. The fresh weight of the shoots and roots was measured immediately using an electronic balance. For dry weight determination, the same parts were dried in an oven at 70 °C for 72 h or until a constant weight was achieved. The dry weights of the shoot and root were then recorded using the same electronic balance.

Physiological attributes

Chlorophyll content, proline and electrolyte leakage

Chlorophyll content was measured using a portable chlorophyll meter (Model: 502, Konica Minolta Sensing, Inc., Japan) following the method described by Dong et al.21. Fresh leaf samples were collected, and the device was used to take readings from multiple points on each leaf. Proline content was determined according to the method of Khan et al.22. Fresh plant tissue, 0.5 g was homogenized in 10 mL of 3% sulfosalicylic acid. The homogenate was filtered, and 2 mL of the filtrate was reacted with 2 mL of acid ninhydrin and 2 mL of glacial acetic acid in a test tube. The mixture was heated at 100 °C for 1 h and then cooled in an ice bath. The reaction mixture was extracted with 4 mL of toluene, and the absorbance of the toluene layer was measured at 520 nm using a spectrophotometer. For electrolyte leakage, a measure of membrane stability was assessed following the method described by Mushtaq et al.23. Tomato leaf discs (approximately 110 mg) were rinsed with deionized water and incubated in test tubes containing 20 mL of deionized water at room temperature for 28 h. Initial conductivity (C1) was measured from the incubation solution to establish baseline electrolyte leakage. Subsequently, leaf samples were boiled for 90 min and allowed to cool to room temperature, after which final conductivity (C2) was measured. Electrolyte leakage was calculated as the percentage proportion of C1 relative to C2, in tomato leaves.

Lead content analysis in plant tissues

Lead content in root, shoot, and fruit samples was analyzed to assess the uptake and accumulation of lead by tomato plants24. The samples were thoroughly washed with deionized water to remove any surface contaminants and then oven-dried at 70 °C for 24 h to a constant weight. The dried samples were ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. A 0.5 g sample of the ground material was digested in a 10 mL mixture of HNO2 and HClO4 (3:1 v/v) overnight to ensure a complete breakdown of the plant material. The next day, the samples were heated on a hot plate until the digest became clear, indicating complete digestion. The digest was then diluted to a final volume of 50 mL with distilled water and filtered through Whatman No. 42 filter paper to remove any particulates. Quality control was ensured by including standard materials such as lead sulfate and lead chloride in the analysis. The lead content in the prepared samples was measured using an Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer, which provides precise quantification of lead concentrations in the plant tissues.

Evaluation of antioxidant enzymes activities

The activities of antioxidant enzymes, including catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), and superoxide dismutase (SOD), were evaluated in the roots and shoots of tomato plants.

Catalase (CAT) activity

CAT activity was measured spectrophotometrically at 240 nm following the method of Mukhtar et al.25, with some modifications26. Fresh plant tissue (0.5 g) was homogenized in 5 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1 mM EDTA. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was used for enzyme assays. The reaction mixture consisted of 2 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 1 mL of 30% H2O2, and 50 µL of enzyme extract. The decrease in absorbance at 240 nm was recorded for 3 min. One unit of catalase activity was defined as the decomposition of 1 mmol H2O2 or µmol H2O2 per min.

Peroxidase (POD) activity

POD activity was determined using the method described by Zhang and Shao27, with some modifications. Fresh plant tissue (0.5 g) was homogenized in 5 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.1). The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was used for enzyme assays. The reaction mixture contained 2 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.1), 1 mL of 20 mM guaiacol, 1 mL of 30% H2O2, and 50 µL of enzyme extract. The increase in absorbance at 470 nm was recorded for 3 min. One unit of POD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of 1 µmol of guaiacol per min.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

SOD activity was determined using the method of Elavarthi and Martin28. Fresh plant tissue (0.5 g) was homogenized in 5 mL of extraction buffer containing 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) and 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP). The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was used for enzyme assays. The reaction mixture contained 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 13 mM methionine, 75 µM nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT), 0.1 mM EDTA, and 2 µM riboflavin. The increase in absorbance at 560 nm was measured after illuminating the reaction mixture for 15 min under fluorescent light. One unit of SOD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to cause 50% inhibition of NBT reduction.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test with IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22.0. All measurements were conducted at least in triplicate, and the results were presented as mean values. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05. Data visualization was performed using OriginPro 2020 (OriginLab Co., Northampton, MA, USA).

Results and discussion

Plant growth parameters

Effect of different lead (Pb) levels (0, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 mg kg−1) in growth media on tomato plant growth parameters: shoot and root length, fresh and dry weight, under three different conditions with no inoculation, inoculation with PGPR strains S5 and S10. Data are presented as means ± standard error (SE) from at least three replicates. Two-way ANOVA was performed to assess the effects of Pb levels, inoculation treatment and their interaction on each growth parameter. Different lowercase letters above bars within each Pb level indicate significant differences among treatments and different uppercase letters indicate significant differences across Pb levels within the same treatment, based on Tukey’s HSD test at p < 0.05.

The results presented in Fig. 2 illustrate the impact of Pb stress and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) inoculation on the growth parameters of tomato plants. As the concentration of Pb in the growth media increased, there was a general decline of about 0.18–57.62% in plant growth metrics, including shoot length, root length, shoot fresh weight, root fresh weight, shoot dry weight, and root dry weight in plants grown in non-inoculated media. This decline is consistent with previous studies demonstrating the detrimental effects of Pb on plant growth, including stunted growth and reduced biomass accumulation due to Pb-induced oxidative stress and nutrient imbalances22,29,30,31.

In contrast, plants inoculated with PGPR strains S5 and S10 exhibited improved growth, with increases of approximately 3.66–95.79%, including 18.73–65.80% in shoot length, 32.77–95.79% in root length, 3.66–14.19% in shoot fresh weight, and 5.14–17.39% in root fresh weight compared to non-inoculated controls, particularly at higher Pb concentrations. For example, at 500 mg kg−1 Pb, inoculation with strain S10 resulted in significantly longer shoot length (41.45 cm) and root length (34.95 cm), as well as higher shoot fresh weight (137.8 g), and root fresh weight (17.46 g), compared to the non-inoculated plants with a shoot length of 25 cm and root length of 17.85 cm, shoot fresh weight of 132.93 g, and root fresh weight of 19.95 g. The improved growth observed in inoculated plants under Pb stress can be attributed to the plant growth-promoting traits of the rhizobacteria, such as enhanced nutrient uptake, phytohormone production, and mitigation of oxidative stress, which have been reported in several studies30,32,33,34,35. The dry weights of both shoots and roots followed a similar trend, with inoculated plants generally showing higher values (5.24–33.89%) than non-inoculated ones across all Pb concentrations. Notably, between the two bacterial strains, strain S10 consistently promoted better growth outcomes than strain S5, especially at elevated Pb levels. This suggests that strain S10 may possess more efficient mechanisms to alleviate Pb toxicity, possibly through more effective secretion of organic acids, siderophores, or other chelating agents that bind to Pb, thereby reducing its availability to plants.

Additionally, Statistical analyses using the two-way ANOVA confirmed the significance of Pb levels, inoculation treatments, and their interaction on growth parameters (p < 0.05). Each graph in Fig. 2 displays the lowercase and uppercase letters for each factor and their combinations, highlighting the substantial impact of PGPR inoculation on mitigating Pb toxicity. The significant results can be attributed to the multifaceted interactions between Pb stress and PGPR inoculation, where PGPR not only enhances nutrient availability but also induces physiological changes in the plant, thereby improving stress resilience. These findings underscore the potential of PGPR inoculation, especially with strain S10, to enhance plant resilience in Pb-contaminated environments, likely through mechanisms such as phytohormone production, oxidative stress reduction, and improved nutrient uptake.

Physiological attributes

Impact of varying Pb levels in growth media (0, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 mg kg−1) on physiological attributes of tomato plants, such as chlorophyll content, proline levels, electrolyte leakage, and Pb accumulation, under three treatment conditions: no inoculation, inoculation with PGPR strains S5 and S10. Data are presented as means ± standard error (SE) from at least three replicates. A two-way ANOVA was performed to assess the effects of Pb levels, inoculation treatment and their interaction on each parameter. Different lowercase letters above bars within each Pb level indicate significant differences among treatments, while different uppercase letters indicate significant differences across Pb levels within the same treatment, according to Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05).

The results presented in Fig. 3 highlight the physiological responses of tomato plants to Pb stress and the mitigating effects of PGPR inoculation strains S5 and S10. As Pb levels in the growth medium increased, a significant decrease in chlorophyll content (SPAD) from 33.28 to 16.58 was observed in non-inoculated plants, underscoring the negative impact of Pb on photosynthesis. This decline in chlorophyll content aligns with existing literature, which reports that Pb interferes with chlorophyll synthesis, leading to reduced photosynthetic efficiency36. The two-way ANOVA results, as denoted by lowercase and uppercase letters in Fig. 3, confirmed a significant interaction between Pb levels and inoculation treatments (p < 0.05). This significant interaction underscores the role of PGPR inoculation in modulating the detrimental effects of Pb stress on chlorophyll content. Specifically, inoculation with PGPR strains S5 and S10 mitigated the decline in chlorophyll content at all tested Pb levels (0–500 mg kg−1), with strain S10 demonstrating particularly robust protective effects at higher Pb concentrations. Given the central role of chlorophyll in photosynthesis, the enhanced chlorophyll retention in inoculated plants suggests improved photosynthetic activity under Pb stress, thereby contributing to sustained plant growth and productivity in contaminated environments.

Proline content, which serves as a marker for stress tolerance, increased (25.23–40.75 µmol g−1 F.W.) across all treatments as Pb levels rose, indicating a stress response. The two-way ANOVA indicated a highly significant effect of Pb levels and inoculation on proline accumulation, with a significant interaction (p < 0.05) between the two factors. The interaction suggests that the proline response to Pb stress was enhanced by rhizobacterial inoculation. Notably, plants grown in media inoculated with strains S5 and S10 exhibited higher proline accumulation than non-inoculated plants, especially at lower Pb concentrations. This suggests that these rhizobacteria may enhance the plant’s stress tolerance mechanisms, potentially by promoting proline biosynthesis, which acts as an osmo-protectant stabilizing proteins and membranes under stress.

Electrolyte leakage, an indicator of membrane damage, also increased with higher Pb concentrations. Non-inoculated plants exhibited the highest levels of leakage, around 52.83%, particularly at a Pb level of 500 mg kg−1, consistent with the known disruptive effects of Pb on cellular membranes11. The two-way ANOVA confirmed a significant interaction (p < 0.05) between Pb concentration and inoculation treatment on electrolyte leakage. This interaction indicates that rhizobacterial inoculation provided a protective effect, reducing electrolyte leakage by 2.41–16.07% across varying Pb levels. This reduction in electrolyte leakage suggests that these bacteria might help maintain membrane integrity, possibly through antioxidant production or by reducing Pb bioavailability within plant tissues.

In terms of Pb accumulation, the concentration of Pb in tomato plant tissues increased with rising Pb levels in the growth media. Specifically, Pb accumulated from 0 to 127.83 mg kg−1 in shoots, 0 to 210.99 mg kg−1 in roots, and 0 to 44.17 mg kg−1 in fruits as Pb concentrations in the media increased from 0 to 500 mg kg−1. Two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of both Pb concentration and PGPR inoculation on Pb accumulation in roots, shoots, and fruits, with a notable interaction effect (p < 0.05) observed in roots and shoots. This interaction suggests that the rhizobacteria influenced the distribution of Pb within the plant tissues. Interestingly, plants grown in media inoculated with strains S5 and S10 accumulated more Pb in their shoots and roots compared to non-inoculated plants. This finding suggests that these rhizobacteria might enhance Pb uptake or translocation within the plant, potentially by altering root interactions with Pb in the soil or modifying Pb transport mechanisms9. An intriguing observation was noted regarding Pb accumulation in the fruit of tomato plants. At a Pb concentration of 100 mg kg−1, plants grown in media inoculated with strains S5 and S10 accumulated more Pb (20–24.37 mg kg−1) in their fruit compared to non-inoculated plants (19.92 mg kg−1). This result contrasts with the trend observed at higher Pb concentrations, where less Pb was detected in the fruit of inoculated plants. This contrasting effect may be due to several factors, such as changes in Pb translocation pathways or alterations in Pb binding and sequestration within plant tissues. Inoculated plants might have developed enhanced mechanisms to compartmentalize Pb, reducing its accumulation in the fruit as Pb concentrations increase.

Antioxidant enzymes activities

Impact of increasing Pb levels in growth media (0, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 mg kg−1) on the activity of key antioxidant enzymes catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in tomato plants under three treatment conditions: no inoculation, inoculation with PGPR strains S5 and S10. Data are expressed as means ± standard error (SE) from at least three replicates. A two-way ANOVA was performed to assess the effects of Pb levels, inoculation treatment and their interaction on each parameter. Different lowercase letters above bars within each Pb level indicate significant differences among treatments, while different uppercase letters indicate significant differences across Pb levels within the same treatment, measured by Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05).

The activities of the antioxidant enzymes catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were significantly influenced by lead (Pb) concentrations in the growth media and by inoculation treatments, as shown in Fig. 4. A two-way ANOVA confirmed that Pb levels, inoculation with PGPR strains S5 and S10, and their interaction had highly significant effects on the activities of these enzymes (p < 0.05), emphasizing the critical role of PGPR in modulating plant responses to Pb stress. CAT activity increased notably with higher Pb levels, especially at 500 mg kg−1 Pb, reflecting an elevated response to oxidative stress. Plants grown in media inoculated with strains S5 and S10 demonstrated the highest CAT activity (0.64–0.68 units mg−1 protein) at this concentration, surpassing non-inoculated plants. This indicates that strains S5 and S10 are particularly effective at enhancing the antioxidative defence system against Pb-induced oxidative stress. POD activity also increased with Pb concentration, with the highest values (5.23–5.95 units mg−1 protein) observed at 400 and 500 mg kg−1 Pb. Strain S10 consistently showed higher POD activity across all Pb concentrations compared to S5 and non-inoculated plants, indicating that strain S10 enhances the plant’s ability to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) under Pb stress. SOD activity generally increased with higher Pb levels, following a trend similar to other antioxidant enzymes. Plants inoculated with strains S5 and S10 exhibited higher SOD activity up to 400 mg kg−1 Pb, but a slight decline was observed at 500 mg kg−1 Pb, possibly due to high Pb levels disrupting cellular processes and SOD activity11.

Overall, inoculation with PGPR strains S5 and S10 likely enhances antioxidant enzyme activities, boosting natural defence mechanisms and activating various antioxidant pathways32. This increased enzymatic activity suggests that the bacterial strains effectively bolster the plants protective responses, contributing to better overall health and vigour by reducing oxidative damage and maintaining cellular integrity34, thus improving growth and productivity even under Pb stress conditions.

Conclusion

This study reveals the detrimental effects of lead stress on tomato plants, manifesting as reduced growth, physiological decline, and increased oxidative damage. However, the application of lead-tolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) strains S5 and S10 proved effective in mitigating these effects. The treatment with PGPR led to notable improvements in key growth parameters and physiological traits, such as enhanced shoot and root growth, reduced electrolyte leakage, and increased antioxidant enzyme activities. Additionally, PGPR strains were effective in lowering lead accumulation in the fruit, suggesting their potential role in minimizing lead bioavailability and translocation to edible parts. Nonetheless, the lead levels in the fruit are still a concern, as they could potentially surpass the safety thresholds set by regulatory authorities. Future research should delve into the specific mechanisms by which PGPR strains influence lead uptake and distribution in tomato plants, and explore practical applications of these findings in field conditions to ensure both crop safety and productivity.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Chaudhary, P., Sharma, A., Singh, B. & Nagpal, A. K. Bioactivities of phytochemicals present in tomato. J. Food Sci. Technol. 55, 2833–2849 (2018).

Collins, E. J., Bowyer, C., Tsouza, A. & Chopra, M. Tomatoes: An extensive review of the Associated Health their cultivation. Biology (Basel). 11, 239 (2022).

Kumar, S. et al. Hazardous heavy metals contamination of vegetables and food chain: Role of sustainable remediation approaches - a review. Environ. Res. 179, 108792 (2019).

Munir, N. et al. Heavy metal contamination of natural foods is a serious health issue: A review. Sustain 14, 161 (2022).

Ankush et al. Source and distribution of lead in soil and Plant—A review. Environ. Sci. Eng. 1251, 3–16 (2023).

Ankush et al. Sewage sludge impacts on yields, nutrients and heavy metals contents in Pearl Millet–Wheat System grown under saline environment. Int. J. Plant. Prod. 15, 93–105 (2021).

Waseem, A. et al. Pollution Status of Pakistan: A retrospective review on heavy metal contamination of water, soil, and vegetables. Biomed Res. Int. 813206 (2014). (2014).

Navabpour, S., Yamchi, A., Bagherikia, S. & Kafi, H. Lead-induced oxidative stress and role of antioxidant defense in wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 26, 793–802 (2020).

Ur Rahman, S. et al. Pb uptake, accumulation, and translocation in plants: Plant physiological, biochemical, and molecular response: A review. Heliyon 10, e27724 (2024).

Han, H. et al. Effects of lead stress on growth and physiology of Pogonatherum crinitum. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 27, 131–138 (2018).

Collin, S. et al. Bioaccumulation of lead (pb) and its effects in plants: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Lett. 3, 100064 (2022).

Aslam, M. et al. Lead toxicity in Cereals: Mechanistic insight into toxicity, Mode of Action, and management. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 587785 (2020).

Liu, N. et al. Non-phytoremediation and phytoremediation technologies of integrated remediation for water and soil heavy metal pollution: A comprehensive review. Sci. Total Environ. 948, 174237 (2024).

You, Y., Dou, J., Xue, Y., Jin, N. & Yang, K. Chelating agents in assisting phytoremediation of uranium-contaminated soils: A review. Sustain 14, 6379 (2022).

Sharma, J. K., Kumar, N., Singh, N. P. & Santal, A. R. Phytoremediation technologies and their mechanism for removal of heavy metal from contaminated soil: An approach for a sustainable environment. Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 1076876 (2023).

Babu, S. M. O. F. et al. Phytoremediation of toxic metals: A sustainable green solution for clean environment. Appl. Sci. 11, 10348 (2021).

Sahoo, R. et al. Unveiling the potential of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) in phytoremediation of heavy metal. Discov Appl. Sci. 6, 324 (2024).

Alves, A. R. A., Yin, Q., Oliveira, R. S., Silva, E. F. & Novo, L. A. B. Plant growth-promoting bacteria in phytoremediation of metal-polluted soils: Current knowledge and future directions. Sci. Total Environ. 838, 156435 (2022).

Saleem, M., Asghar, H. N., Zahir, Z. A. & Shahid, M. Evaluation of lead tolerant plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for plant growth and phytoremediation in lead contamination. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient. 35, 999–1009 (2019).

Li, S. et al. Glycinebetaine enhances the tolerance of tomato plants to high temperature during germination of seeds and growth of seedlings. Plant. Cell. Environ. 34, 1931–1943 (2011).

Dong, T. et al. Assessment of Portable Chlorophyll meters for Measuring Crop Leaf Chlorophyll Concentration. Remote Sens. 11, 2706 (2019).

Khan, M. et al. Lead (Pb)-induced oxidative stress alters the morphological and physio-biochemical properties of rice (Oryza sativa L). Agronomy 11, 1–16 (2021).

Mushtaq, N. et al. Melatonin in Micro-Tom Tomato: Improved drought tolerance via the regulation of the photosynthetic apparatus, membrane stability, osmoprotectants, and root system. Life 12, 1922 (2022).

Singh, R. P. & Agrawal, M. Variations in heavy metal accumulation, growth and yield of rice plants grown at different sewage sludge amendment rates. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 73, 632–641 (2010).

Mukhtar, A., Latif, S., Salvatierra-Rojas, A. & Müller, J. Catalase activity in Hot-Air Dried Mango as an indicator of heat exposure for rapid detection of heat stress. Appl. Sci. 12, 1305 (2022).

Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 105, 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(84)05016-3 (1984).

Zhang, X. & Shao, X. Characterisation of Polyphenol Oxidase and Peroxidase and the role in Browning of Loquat Fruit. Czech J. Food Sci. 33, 109–117 (2015).

Elavarthi, S. & Martin, B. Spectrophotometric assays for antioxidant enzymes in plants. in Plant Stress Tolerance (ed Sunkar, R.) vol. 639 273–279 (Springer Science + Business Media, (2010).

Zulfiqar, U. et al. Lead toxicity in plants: Impacts and remediation. J. Environ. Manage. 250, 109557 (2019).

Gupta, M. et al. Lead toxicity in plants: Mechanistic insights into toxicity, physiological responses of plants and mitigation strategies. Plant. Signal. Behav. 19, e2365576 (2024).

Aslam, M. et al. Lead toxicity in Cereals: Mechanistic insight into toxicity, Mode of Action, and management. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 587785 (2021).

Backer, R. et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: Context, mechanisms of action, and roadmap to commercialization of biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant. Sci. 871, 1473 (2018).

Nazli, F. et al. A review on practical application and potentials of phytohormone-producing plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for inducing heavy metal tolerance in crops. Sustain 12, 9056 (2020).

Bhat, M. A. et al. Plant Growth promoting Rhizobacteria in Plant Health: A perspective study of the Underground Interaction. Plants 12, 629 (2023).

Ma, Y., Oliveira, R. S., Freitas, H. & Zhang, C. Biochemical and molecular mechanisms of plant-microbe-metal interactions: Relevance for phytoremediation. Front. Plant. Sci. 7, 918 (2016).

Qin, J. et al. Effects of lead Pollution on photosynthetic characteristics and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of different populations of Miscanthus floridulus. Processes 11, 1562 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SA conceived the idea, designed the research and performed the experiments; MS, AM, TH, ML, AB and MWA analysed data. SA wrote the manuscript. AM, QA, and MIA provided technical support and proofread the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval was required for this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anjum, S., Sarwar, M., Mukhtar, A. et al. Impact of rhizobacterial inoculation in plant growth medium to mitigate lead stress in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Sci Rep 15, 707 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84648-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84648-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Application of Melatonin and Bacillus halotolerans Mitigated the Cadmium and Lead Induced Toxicity in Brassica carinata by Improving the Growth and Defense System of the Plant

Journal of Plant Growth Regulation (2026)

-

Effect of Compost and Lead Tolerant Bacillus sp. Strain N18 on Growth and Pb Uptake in Tomato Plants

Waste and Biomass Valorization (2025)