Abstract

Flash flood susceptibility mapping is essential for identifying areas prone to flooding events and aiding decision-makers in formulating effective prevention measures. This study aims to evaluate the flash flood susceptibility in the Yarlung Tsangpo River Basin (YTRB) using multiple machine learning (ML) models facilitated by the H2O automated ML platform. The best-performing model was used to generate a flash flood susceptibility map, and its interpretability was analyzed using the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) tree interpretation method. The results revealed that the top four models, including both single and ensemble models, demonstrated high accuracy in the tests. The flash flood susceptibility map generated by the best-performing eXtreme Randomized Trees (XRT) model showed that 8.92%, 12.95%, 15.42%, 31.34%, and 31.37% of the study area exhibited very high, high, moderate, low, and very low flash flood susceptibility, respectively, with approximately 74.9% of the historical flash floods occurring in areas classified as moderate to very high susceptibility. The SHAP plot identified topographic factors as the primary drivers of flash floods, with the importance analysis ranking the most influential factors in such descending order as DEM, topographic wetness index, topographic position index, normalized difference vegetation index, and average multi-year precipitation. This study demonstrates the benefits of interpretable machine learning, which can provide guidance for flash flood mitigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The accumulation of heavy precipitation typically occurs within a short period of time, exceeding the drainage capacity of mountain streams and slopes and thus causing flash floods1,2. Flash floods not only may lead to grave consequences such as causalities, they may also cause damage to property, including private houses, farmland, and infrastructure3. Flash floods pose a significant threat to public safety and economic activities4,5. Flash floods are characterized by their suddenness, intensity, destructiveness, and short duration6,7, making them one of the most dangerous types of floods8,9.

The assessment of flash flood susceptibility is a crucial aspect of flash flood research, typically developed based on two types of models10: (1) Parametric models (physically-based models) such as Hydrologic Engineering Center’s River Analysis System (HEC-RAS)11, Hydrologic Engineering Center’s Hydrologic Modeling System (HEC-HMS)12, and Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT)13. These models are theoretically robust in scientific terms; however, they face challenges in practical applications, such as high computational demands, difficulties in parameter calibration, and high development and maintenance costs11. Moreover, issues like scale effects and other limiting factors can affect the accuracy of these models14,15. (2) Non-parametric models (data-driven models), including Random Forest (RF)16, Support Vector Machine (SVM)17, Logistic Regression (LR)18, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)19. These models do not rely on a detailed description of the physical process20, but generally use a certain algorithmic structure, and then adjust their parameters to the data (training), as well as their complexity by optimizing the bias-variance trade-off, so that the fitted model generalizes well to new data20. Such methods have achieved significant results in practical applications21,22. Additionally, researchers are also exploring methods to integrate physical models with data-driven models to achieve more accurate predictive results23.

The development of ML models, as well as hybrid models (hybrid models are defined as models that integrate multiple machine learning algorithms)24, has sparked increased interest in model interpretability24,25,26,27. Although model interpretability has been a concern for a long time and depends on the types of models used, many ML models have remained difficult to understand due to their complexity (e.g., complex structures and parameters28, non-linear interactions29, and the “black box” nature30), leading to significant challenges in explaining their predictive outcomes. However, the H2O Automated ML (Auto-ML) platform provides access to a range of predictive models, automated model selection, and model parameter (hyper-parameters) tuning as well as integrates methods for model interpretability. This constitutes an advancement for making decisions about the suitability of the modelling process31.

Flash floods typically result from a combination of factors25. Particularly in the YTRB, flash floods are frequent due to the region’s complex terrain and weather patterns, which make prediction particularly challenging32. Research on the YTRB has strongly focused on the response of precipitation, runoff, and land use to climate change33,34,35. In terms of flood research, the main focus has been on flood mechanisms such as glacial lake outbursts and localized debris flows36, while flash flood susceptibility has not been extensively investigated. Flash flood susceptibility research will not only help to understand the influencing factors of flash floods, but also provide a reference for policy formulation and enhanced local flash flood prevention and mitigation37.

This study explores the use of auto-ML for flash flood susceptibility mapping in the YTRB, responding to the urgent need for these tools in the region, and conducts interpretability analysis of the results. The innovation of the study is reflected in the following aspects: the introduction of advanced Auto-ML techniques to enhance model efficiency and accuracy; the integration of interpretability analysis methods to make the model results transparent and credible; and, the provision of quick, accurate and up-to-date flash flood susceptibility mapping for the YTRB. Based on this, our research objectives are: (1) to identify and evaluate the influencing factors of flash floods; (2) to select and evaluate machine learning models; (3) to conduct flash flood susceptibility mapping; and (4) to perform interpretability analysis on the results of the optimal model.

Materials and methods

Study area

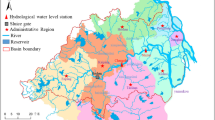

The YTRB (82°00′ E to 97°07′ E, 28°00′ N to 31°16′ N) is situated in the southern part of the Tibetan Plateau, covering a total area of approximately 240,000 km2 (Fig. 1). The topography of the basin is characterized by higher elevations in the west, north and south, with lower elevations in the east and middle. The average altitude exceeds 4000 m38. The main valley of the YTRB follows an east-west fault zone, giving the basin an elongated shape. Situated in this tectonic fault zone, the YTRB experiences frequent earthquakes and active geological processes36. Major tributaries include the Lhasa River, Parlung Tsangpo, Yigong Tsangpo, Lhoka Tsangpo, Nizequ, and Nianchu River39.

The eastern region of the YTRB receives over 900 mm of annual precipitation, while the western region gets less than 100 mm, making it arid. The spatial and temporal distribution of precipitation within the basin is extremely uneven40, the occurrence time and intensity of extreme precipitation range from 25 to 50 mm/day38. Vegetation in the basin includes alpine meadow and steppe in the upper reaches, shrub lands and forests in the middle, and coniferous and broadleaf forests in the lower reaches. The southeastern area, influenced by the tropical monsoon, is dominated by broadleaf forests. The main soil types are mountainous shrub-steppe soils and alpine steppe soils.

Data

Flash flood inventory data

Flash flood inventory records document a series of events caused by intense rainfall41. Analyzing historical flash flood data is essential for mitigating flood-related damage and enhancing preventative measures42. The flash flood inventory data used in this study covers the period from 1980 to 2019, primarily sourced from the China Flash Flood Investigation Project, with supplementary information from online news media and government records. The data attributes include the geographic location, year, and month of occurrence of the disasters (Table 1). Since the 1980s, the YTRB has experienced 605 documented flash floods (Fig. 1). Additionally, we utilized ArcGIS 10.8 software to randomly generate 605 non-flash flood points within the study area. Historical flash floods data suggests that geographic and environmental factors contribute to the susceptibility of certain areas to flash floods, indicating that regions with similar attributes may also experience such events.

Factors influencing flash floods

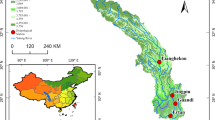

An adequate selection of factors influencing flash floods is crucial for predicting flash flood susceptibility. We selected 20 factors (Table 2) based on previous studies43,44,45,46,47. These factors are categorized into meteorological and surface factors. Meteorological factors include annual maximum 3-hourly precipitation (3-H-P), annual maximum 6-hourly precipitation (6-H-P), annual maximum 12-hourly precipitation (12-H-P), annual maximum 24-hourly precipitation (24-H-P), and average multi-year precipitation (AP). The long-term average precipitation is indicative of the overall soil humidity in the region. Spatial interpolation was applied to annual mean precipitation data from meteorological stations for the years 1980–2015 (Fig. 2a). In contrast, extreme precipitation indices highlight the potential for intense, short-duration downpours. The maximum 3-hourly precipitation values were derived from China Meteorological Forcing Dataset (CMFD), for the years 2011–2015 (Fig. 2b).

Surface factors include slope (SL), aspect (AS), plan curvature (PLC), profile curvature (PRC), terrain ruggedness index (TRI), topographic position index (TPI), topographic wetness index (TWI), stream power index (SPI), river density (RD), distance from river (DFR), soil type (ST), lithology (LI), normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), and land use/land cover (LULC). All factors influencing flash floods were resampled to a spatial resolution of 1 km.

Topography plays a crucial role in influencing the speed and direction of surface runoff, with steep slopes facilitating the rapid downhill flow of water48. Utilizing 90-meter spatial resolution STRM DEM data, the study area was cropped to its boundaries (Fig. 2c). Aspect (Fig. 2d) affects the direction of surface runoff49. The PLC and PRC (Fig. 2e and f) determine the direction and speed of runoff, which influences the accumulation or dispersion of water on the terrain. The TPI measures the relative elevation and terrain variability at specific points (Fig. 2g). The TWI indicates how the topography influences the water flow paths and water accumulation and soil saturation potential (Fig. 2h), demonstrating the impact of the terrain on moisture retention50. The SPI reveals the layout of the river system and its potential water conveyance capacity (Fig. 2i)51. Indices such as RD and DFR indicate the hydrological status of the location (hydrological status refers to characteristics such as the distribution, flow, and availability of water bodies in the region) as shown in Fig. 2j and k52. ST (Fig. 2l) can affect surface runoff by affecting infiltration. For example, clayey soils may restrict infiltration during heavy rainfall events. The LI can affect water infiltration, so geologic structures that are susceptible to erosion can exacerbate flooding during heavy rainfall events (Fig. 2m)2. The NDVI is extensively used as a vegetation condition index to effectively differentiate between healthy land cover and areas that are either unhealthy or lacking vegetation (Fig. 2n)2. The Changes of LULC affects the permeability of water (Fig. 2o), thereby affecting surface runoff53. The methods for calculating the TPI, TWI and SPI indices are as follows:

Where Z is the elevation value at a specific point, and \(~{Z_{mean}}\) is the average elevation of the surrounding points. Positive TPI values typically indicate ridges, negative values indicate valleys, and values near zero indicate flat areas.

Where A is the water flow accumulation, and β is the local slope angle in radians. TWI is used to identify areas that may be saturated due to water flow accumulation, often wetlands or valleys. A higher TWI value indicates greater potential for saturation.

The SPI is used to estimate the erosive power of water flow at a given point. It is a function of water flow accumulation and the steepness of the slope. Higher SPI values indicate stronger erosive potential.

Methods

Based on the initially selected flash flood influencing factors, this study involves processes such as factor selection, ML model training, model evaluation, flash flood susceptibility mapping, and model interpretation. A flowchart of the approach used in this study is shown in Fig. 3.

Correlation and multi-collinearity analysis

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient is a non-parametric statistical method ideal for analyzing data that does not require a normal distribution or linear relationship. It evaluates the monotonic relationship between variables by ranking the data, which enhances its robustness to outliers. Its simplicity in calculation makes it particularly well-suited for ordinal data, especially when the conditions for traditional parametric tests are not met54. As such, it is commonly employed to assess the correlation between each pair of different factors.

Multi-collinearity refers to the condition where multiple independent variables exhibit high correlation with each other, potentially causing instability in statistical models and leading to inaccurate parameter estimates. This, in effect, compromises the model’s predictive accuracy and interpretative clarity. Therefore, it is essential to assess and address multicollinearity when selecting factors that may influence flash floods. Multi-collinearity analysis is evaluated using Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs), where:

-

1.

A VIF of 1 indicates no multi-collinearity.

-

2.

A VIF between 1 and 5 suggests a moderate level of multi-collinearity, which is usually acceptable.

-

3.

While a VIF above 5 indicates strong multi-collinearity55.

H2O Auto-ML platform

H2O is an open-source, distributed ML platform that automates the training and testing of multiple ML models efficiently56. It employs a combination of rapid stochastic search and layered integration to attain results. The H2O Auto-ML workflow encompasses several key stages such as data preprocessing, features engineering (the process of selecting, modifying, or creating new features from raw data to improve the performance of ML models), hyper-parameter tuning, model performance evaluation, and interpretability57.

H2O Auto-ML constructs multiple types of ML models, including Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), Distributed Random Forest (DRF), Generalized Linear Models (GLM), deep learning architectures, eXtreme Randomized Trees (XRT), and more. Following the individual training of all these models, H2O Auto-ML combines them as Stacked Ensemble All Models (SEAM) and Stacked Ensemble Best Family (SEBF) to make predictions.

Model performance evaluation

The sample data were divided into training (70%) and testing (30%) datasets. Generic statistical metrics were selected to assess the accuracy of the predictions.

Sensitivity, which measures the proportion of actual positive cases (e.g., instances of flash floods) that the model correctly identifies, is defined as:

where true positive (TP) is the number of correctly predicted positive cases, and false negative (FN) is the number of incorrectly predicted negative cases.

Specificity, which measures the proportion of actual negative cases (e.g., instances of no flash floods) that the model correctly identifies, is defined as:

where true negative (TN) is the number of correctly predicted negative cases, and false positive (FP) is the number of incorrectly predicted positive cases.

Accuracy, which measures the overall correctness of the model predictions, combining both positive and negative cases, is defined as:

Precision, which measures the proportion of predicted positive cases that are actually positive, indicating the reliability of positive predictions, is defined as:

The area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), which summarizes in a single metric a model’s overall performance after considering multiple decision boundaries. The closer the ROC curve is to the top-right corner of the plot the better is the model performance. AUC values range from 0.5 to 1, indicating random guessing or perfect discrimination between binary classes, respectively.

Model interpretability and Shapley Additive explanations (SHAP) method

Model interpretability refers to the extent to which the relationship between input factors and output predictions generated by ML models is easy to understand. The SHAP value assigns an importance score to each factor by determining its contribution to the model’s prediction. It represents a factor’s average marginal contribution across all possible factor subsets. This provides an objective measure of how much each factor influences the model’s prediction for flash flood susceptibility58. In the context of H2O Auto-ML’s flash flood model, the SHAP value, \({\phi _i}\), for the i-th factor is calculated as follows:

Where N is the set of all factors, and S is a subset of N, excluding factor i. M is the total number of factors, and \({f_X}\left( S \right)\) represents the model’s output when only the factors in subset S are considered.

The predicted output \(f\left( x \right)\) for any given input x is then explained as:

Where \({\phi _0}~\)represents the baseline contribution to the solution, which is the average predicted output when no factors are considered, and \({\phi _i}\) the factors’ contribution relative to the baseline.

SHAP enhances both local and global interpretability of the H2O Auto-ML model for flash flood susceptibility mapping. Locally, it explains individual predictions by showing how each factor influences the model’s output. Globally, it highlights the most important factors by averaging SHAP values across multiple samples, revealing the factors that consistently impact predictions. Additionally, SHAP assists in factor selection by ranking key factors, facilitating more efficient model optimization and reducing complexity without sacrificing accuracy.

Results

Spearman correlation and multi-collinearity analyses

This study computed Spearman’s coefficient for each pair of factors influencing flash floods, as shown in Fig. 4. The sign of the Spearman’s coefficient determines the direction of correlation between the factors influencing flash flood. The Spearman correlation coefficient ranges from − 1 to 1, with values closer to 0 indicating weaker correlations between the factors influencing flash flood. The analysis reveals that the strongest correlation is between TRI and SL, with a coefficient of 0.98, followed by a negative correlation between RD and DFR, with a coefficient of -0.9. The factors 3-H-P, 6-H-P, 12-H-P, and 24-H-P also exhibit relatively strong positive correlations, with coefficients ranging from 0.71 to 0.88.

The results of the multi-collinearity analysis are presented in Table 3, showing that the smallest VIF is associated to the AS factor and the largest to the 12-H-P factor. The factors 6-H-P, 12-H-P, 24-H-P, SL, and TRI, have VIFs above the threshold of 5 and are excluded from the list of predictors to be used in the ML models of flash flood susceptibility, leaving a final number of 15 factors to be considered.

Model validation and performance evaluation

The learning curves of the models show that the number of iterations for the XRT and DRF models is 36 and 35, respectively (Fig. 5a and b), indicating that these individual models have higher operational efficiency. In contrast, the SEAM and SEBF models required 103 and 122 iterations, respectively (Fig. 5c and d). Stacked models require a longer iteration time to achieve the desired results due to more extensive model training, cross-validation hyper-parameter tuning, and model fusion step—combining the predictions from the multiple base models using an additional ML model, the meta-learner.

In the training set results, the XRT model demonstrated the best performance, with an AUC value of 0.9671, followed by DRF (0.9669), SEAM (0.9668), and SEBF (0.9665). In the testing set results (Table 4). The sensitivity, which indicates the number of correctly classified floods, was high with values of 0.938 and 0.955 for XRT and SEAM, respectively. Specificity, which refers to the model’s ability to correctly identify non-flash floods, was high for XRT and SEAM, at 0.938 and 0.937, respectively. In contrast, SEBF had the lowest specificity, at 0.887. Accuracy, which indicates the proportion of all predictions where the model correctly predicted flash floods and no flash floods, was highest for XRT and DRF at 0.938, followed by SEAM (with an accuracy of 0.932), and lowest for SEBF (0.924). Precision indicates the percentage of events predicted as flash floods by the model. The highest accuracy (0.938) was found for XRT and SEAM.

In model testing, the AUC values of the four ML models were high (Fig. 6), indicating their high performance in predicting flash flood susceptibility. In fact, the differences between the highest and lowest AUC values among the four models was only 0.006. By comparing at the AUC values for the training set and those for the test set, the XRT was selected for flash flood susceptibility mapping and interpretability analysis.

Flash flood susceptibility mapping

For each raster cell, the XRT model trained with 15 factors influencing flash floods was used to estimate flood susceptibility. The results were then classified using the natural breaks method, which is widely used in similar studies44,59. The flash flood susceptibility was classified into five levels: very low, low, moderate, high, and very high. As shown in Fig. 7 and 8.92% and 12.95% of the study area fall into very high and high flood susceptibility levels, respectively; 31.37% and 31.34% of the area fall into very low and low flood susceptibility levels, respectively; and the remaining 15.42% of the area falls into the moderate flood susceptibility level.

In the flash flood susceptibility map, the western and central parts of the basin present very high and high susceptibility levels, while the eastern regions have fewer areas with such flash flood susceptibility. When overlaying the (represented by points in the map), 74.9% of historical flash floods occurred in areas classified as moderate to very high flash flood susceptibility.

Analysis of model interpretability

The global importance of the factors influencing flash floods was evaluated by computing the mean absolute SHAP values across all the observations. The SHAP summary plot in Fig. 8, illustrates the positive and negative impacts of the factors on the prediction outcomes. It identified the DEM as the most important factor, whereas LULC is the least important factor. The DEM emerged as the dominant factor possibly due to the YTRB’s location in the southeast of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, which is characterized by complex topography and significant elevation differences. In such a geographic environment, changes in elevation have a direct impact on a variety of natural processes such as surface water flow and climate. Concurrently, changes in altitude lead to significant variations in vegetation type and coverage, which affect the infiltration and evaporation of surface water. As such, the importance of LULC is lower, likely because of the limited impact of human activities and minimal land-use changes in remote and high-altitude areas, rendering the effect of land-use change on hydrological processes less significant than other factors. Overall, the five main factors influencing flash floods are all topography-related (DEM, TWI, TPI, AS, and SPI), indicating that topography is dominant. This was followed by the meteorological factor 3-H-P and surface factor NDVI. Hydrological factors such as river network density and river network distance have limited impact on flash floods.

In many cases, the rankings of factors in the SHAP plot and factor importance plot (Fig. 9) exhibit comparable patterns. However, the SHAP value offers a local interpretation of individual prediction outcomes, whereas the factor importance provides an overall perspective. The first three dominant factors (DEM, TWI, and TPI) are consistent between the two plots, which reinforces the idea that topographic factors are the most important factors influencing flash floods in this study region. Similarly, LULC and hydrological factors are found to have minor influence according to Fig. 9. However, in contrast with the SHAP plot, this figure ranks multi-year average precipitation higher than the 3-H-P.

Discussion

The exploration of the impact of main influencing factors on flash flood susceptibility

In Ma et al.’s study on flash floods in Yunnan Province, China, precipitation, topography, and flood prevention measures were identified as major influencing factors60. However, our study, using the same precipitation dataset, indicates that precipitation is not a primary factor for flash floods in the YTRB. This may be due to the higher precipitation levels and the frequency of extreme rainfall compared to the central and western regions of the YTRB. In the YTRB, the central and western regions experience lower annual precipitation, have numerous river valleys, and more high-susceptibility areas. In contrast, the eastern region has higher annual precipitation, deeply incised canyons, and fewer high-susceptibility areas, indicating that the topography may inhibit the occurrence of flash floods, thereby emphasizing the role of terrain in flood events.

We further explore the mechanisms by which the main influencing factors affect flash floods. Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs), which are suitable for analyzing the relationship between the magnitude of a factor (x-axis) and its impact on predictions (y-axis), are used to investigate specific influences. As depicted in Fig. 10a, the susceptibility to flash floods is not well explained by terrain altitudes exceeding 5000 m. Within the range of 1300–4000 m, the contribution of terrain altitude to explain flash flood susceptibility is notably high in this region. Figure 10b indicates that regions with high TWI values better explain flash flood susceptibility, which can be attributed to increased water accumulation. Figure 10c illustrates that as the TPI increases, the probability of flash flood occurrence exhibits a pattern of rapid escalation followed by a rapid decline. A TPI that falls within the range of – 1.5 to 0.6 significantly contribute to explain flash flood susceptibility. Figure 10d reveals that the NDVI contribution to explain flash flood susceptibility is lower when its value is either exceptionally high or low. Figure 10e shows that when the influence factor (AP) is within the range of 350–500 mm, the model’s average prediction result, which represents flash flood susceptibility, is at a relatively high level. Figure 10f shows that the plane curvature is within a limited range, when the value is higher, its contribution to explain flash floods susceptibility decreases. These findings underscore the complex interplay between topographic, climatic, and vegetation factors in determining flash flood susceptibility.

The implication of the research to local stakeholders

In the YTRB, the middle and lower reaches are covered with fertile soils and well-irrigated forests, making it home to approximately 50% of the population of the Tibet Autonomous Region, including areas such as Shigatse, Lhasa, Lokha County, and Nyingchi38. However, due to the basin’s unique geographical location and complex natural conditions, it often faces threats from natural disasters such as flash floods and landslides. Considering the results of this study and the costs of flash flood prevention, the following recommendations are proposed:

-

1.

Use the flash flood susceptibility maps to inform zoning decisions that better protect communities and property.

-

2.

Screen communities and assets at risk for further studying and for developing mitigation measures, including relocation and safe evacuation routes.

-

3.

Contribute to the development of flash flood risk indicators and potentially to the development of early warning systems.

The limitation of the proposed methodology and future research.

The dataset utilized in this study is constrained by historical limitations in flood statistics within China and the geographical context of the YTRB, which has influenced the results. Our findings indicate that impact factors exhibit variability in both spatial and temporal resolutions, with the spatial resolution of extreme precipitation being particularly in need of enhancement. To address temporal variability, we predominantly employed data from approximately 2015; however, data limitations hindered our ability to thoroughly analyze spatiotemporal dynamics.

Overall, the investigation of flash flood susceptibility in the YTRB, especially in relation to heavy rainfall, poses significant challenges due to difficulties in data acquisition, modeling uncertainties, and the intricate nature of influencing factors. Despite these challenges, this study provides a solid basis for future research in flash flood susceptibility. Future studies should prioritize addressing the discrepancies in spatial and temporal resolutions of various influencing factors, the generalization of flash flood susceptibility models to other regions, and account for the temporal variability of these factors.

Conclusion

In this study, we employed H2O Auto-ML for the inaugural generation of a flash flood susceptibility map for the YTRB. The analysis incorporated 605 flash flood occurrences and utilized 15 influencing factors. To assess the correlations among flood condition parameters, multiple collinearity diagnostic tests (e.g., VIF) and Spearman correlation matrices were conducted for the selection of influencing factors. Utilizing the H2O Auto-ML platform, we developed and validated flood susceptibility models with training and validation datasets, identifying key contributing factors through the SHAP interpretability algorithm. The results indicated that both individual algorithms (e.g., XRT; DRF) and ensemble algorithms (e.g., SEAM; SEBF) based on H2O Auto-ML achieved high performance. With AUC values exceeding 0.97, the XRT model demonstrated the superior performance. In the flash flood susceptibility map generated by the XRT model, areas classified as highly susceptible or above constituted 21.87% of the total area, predominantly distributed in the western and central regions of the YTRB. Furthermore, 74.9% of historical flash flood occurrences were situated in regions classified from moderate to extremely high flood susceptibility. Terrain factors such as DEM, TWI, and TPI proved to be more effective in this study than other considered factors, offering valuable insights for managing population distribution in the YTRB region.

Overall, the XRT model based on H2O Auto-ML offers significant advantages, including rapid computation speed, automatic parameter optimization, and enhanced interpretability, facilitating the prompt development of flash flood susceptibility maps and associated analyses. Fast and accurate flash flood susceptibility mapping constitutes a critical contribution to risk management. This study serves as a reference for other researchers to continue advancing this type of techniques, and it will assist regional planners and local decision-makers in formulating strategies to mitigate the consequences associated with flash flood disasters.

Data availability

The data will be provided based on a request to the corresponding author, Suxia Liu (liusx@igsnrr.ac.cn).

References

Costache, R. et al. Flash flood hazard using deep learning based on H2O R package and fuzzy-multicriteria decision-making analysis. J. Hydrol. 609, 563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.127747 (2022).

Taherizadeh, M., Niknam, A., Nguyen-Huy, T., Mezösi, G. & Sarli, R. Flash flood-risk areas zoning using integration of decision-making trial and evaluation laboratory, GIS-based analytic network process and satellite-derived information. Nat. Hazards. 118, 2309–2335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-023-06089-5 (2023).

Pham, N. T. T., Nong, D. & Garschagen, M. Natural hazard’s effect and farmers’ perception: perspectives from flash floods and landslides in remotely mountainous regions of Vietnam. Sci. Total Environ. 759, 142656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142656 (2021).

Othman, A., El-Saoud, W. A., Habeebullah, T., Shaaban, F. & Abotalib, A. Z. Risk assessment of flash flood and soil erosion impacts on electrical infrastructures in overcrowded mountainous urban areas under climate change. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 236, 109302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2023.109302 (2023).

Yin, J. B. et al. Large increase in global storm runoff extremes driven by climate and anthropogenic changes. Nat. Commun. 9, 4389. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06765-2 (2018).

Gao, D. et al. Modelling and validation of flash flood inundation in drylands. J. Geogr. Sci. 34, 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-024-2201-7 (2024).

Yang, Z. L. et al. Meta-analysis and visualization of the literature on early identification of flash floods. Remote Sens. 14, 3313. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14143313 (2022).

Diakakis, M. et al. Proposal of a flash flood impact severity scale for the classification and mapping of flash flood impacts. J. Hydrol. 590, 125452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125452 (2020).

Ding, L. S. et al. A survey of remote sensing and geographic information system applications for flash floods. Remote Sens. 13, 1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13091818 (2021).

Schweidtmann, A. M., Zhang, D. & Stosch, M. A review and perspective on hybrid modeling methodologies. Digit. Chem. Eng. 10, 100136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dche.2023.100136 (2024).

Costabile, P., Costanzo, C., Ferraro, D. & Barca, P. Is HEC-RAS 2D accurate enough for storm-event hazard assessment? Lessons learnt from a benchmarking study based on rain-on-grid modelling. J. Hydrol. 603, 126962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126962 (2021).

Khan, I. R., Elmahdy, S. I., Rustum, R., Khan, Q. & Mohamed, M. M. Floods modeling and analysis for Dubai using HEC-HMS model and remote sensing using GIS. Sci. Rep. 14, 4586. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74736-3 (2024).

Soomro, S. E. H. et al. River flood susceptibility and basin maturity analyzed using a coupled approach of geo-morphometric parameters and SWAT model. Water Resour. Manag. 36, 2131–2160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-022-03127-y (2022).

Merz, R., Parajka, J. & Blöschl, G. Scale effects in conceptual hydrological modeling. Water Resour. Res. 45, 7485. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009wr007872 (2009).

Dottori, F. & Todini, E. Testing a simple 2D hydraulic model in an urban flood experiment. Hydrol. Process. 27, 1301–1320. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.9370 (2013).

Chen, W. et al. Modeling flood susceptibility using data-driven approaches of naive Bayes tree, alternating decision tree, and random forest methods. Sci. Total Environ. 701, 134979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134979 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Assessment of flood susceptibility mapping using support vector machine, logistic regression and their ensemble techniques in the Belt and Road region. Geocarto Int. 37, 9817–9846. https://doi.org/10.1080/10106049.2022.2025918 (2022).

Al-Juaidi, A. E. M., Nassar, A. M. & Al-Juaidi, O. E. M. Evaluation of flood susceptibility mapping using logistic regression and GIS conditioning factors. Arab. J. Geosci. 11, 785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-018-4095-0 (2018).

Costache, R. et al. Novel hybrid models between bivariate statistics, artificial neural networks and boosting algorithms for flood susceptibility assessment. J. Environ. Manage. 265, 110485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110485 (2020).

Pichler, M. & Hartig, F. Machine learning and deep learning—a review for ecologists. Methods Ecol. Evol. 14, 994–1016. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.14061 (2023).

Al-Ruzouq, R. et al. Flood susceptibility mapping using a novel integration of multi-temporal sentinel-1 data and eXtreme deep learning model. Geosci. Front. 15, 101780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsf.2024.101780 (2024).

Rahmati, O. et al. Development of novel hybridized models for urban flood susceptibility mapping. Sci. Rep. 10, 129387. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69703-7 (2020).

Mo, Z. B., Shi, R. Y. & Di, X. A physics-informed deep learning paradigm for car-following models. Transp. Res. C-Emer. 130, 103240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2021.103240 (2021).

Band, S. S. et al. Flash Flood susceptibility modeling using New approaches of Hybrid and Ensemble Tree-based machine learning algorithms. Remote Sens. 12, 3568. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12213568 (2020).

Habibi, A., Delavar, M. R., Sadeghian, M. S., Nazari, B. & Pirasteh, S. A hybrid of ensemble machine learning models with RFE and Boruta wrapper-based algorithms for flash flood susceptibility assessment. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 122, 103401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2023.103401 (2023).

Pradhan, B., Lee, S., Dikshit, A. & Kim, H. Spatial flood susceptibility mapping using an explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) model. Geosci. Front. 14, 10162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsf.2023.101625 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. An XGBoost-SHAP approach to quantifying morphological impact on urban flooding susceptibility. Ecol. Indic. 156, 111137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.111137 (2023).

Qi, D. & Majda, A. J. Using machine learning to predict extreme events in complex systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1917285117 (2020).

Kang, J., Zhang, B. & Dang, A. A novel geospatial machine learning approach to quantify non-linear effects of land use/land cover change (LULCC) on carbon dynamics. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 128, 103712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2024.103712 (2024).

Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 206–215. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0048-x (2019).

Luo, J. Y. et al. Prediction of biological nutrients removal in full-scale wastewater treatment plants using H2O automated machine learning and back propagation artificial neural network model: optimization and comparison. Bioresour Technol. 390, 129842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2023.129842 (2023).

Wang, N., Cheng, W. M., Wang, B. X., Liu, Q. Y. & Zhou, C. H. Geomorphological regionalization theory system and division methodology of China. J. Geogr. Sci. 30, 212–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-020-1724-9 (2020).

Ye, X. Y., Guo, Y. H., Wang, Z. G., Liang, L. F. & Tian, J. Y. Extensive evaluation of four satellite precipitation products and their hydrologic applications over the Yarlung Zangbo River. Remote Sens. 14, 3350. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14143350 (2022).

Luo, J. et al. Study of the intensity and driving factors of land use/cover change in the Yarlung Zangbo River, Nyang Qu River, and Lhasa River region, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China. J. Arid Land. 14, 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40333-022-0093-x (2022).

Li, C. Y. et al. Runoff variations affected by climate change and human activities in Yarlung Zangbo River, southeastern tibetan Plateau. Catena 230, 107184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.107184 (2023).

An, B. S. et al. Process, mechanisms, and early warning of glacier collapse-induced river blocking disasters in the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, southeastern tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 816, 151653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151652 (2022).

Chen, Y. G., Zhang, X. Y., Yang, K. J., Zeng, S. Y. & Hong, A. Y. Modeling rules of regional flash flood susceptibility prediction using different machine learning models. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1117004. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2023.1117004 (2023).

Sang, Y. F. et al. Precipitation variability and response to changing climatic condition in the Yarlung Tsangpo River basin, China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 8820–8831. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016jd025370 (2016).

Li, S. et al. The evolution of Yarlung Tsangpo River: constraints from the age and provenance of the Gangdese conglomerates, southern Tibet. Gondwana Res. 41, 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2015.05.010 (2017).

Dong, W. H. et al. Summer rainfall over the southwestern Tibetan Plateau controlled by deep convection over the Indian subcontinent. Nat. Commun. 7, 10925. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10925 (2016).

Vennari, C., Parise, M., Santangelo, N. & Santo, A. A database on flash flood events in Campania, southern Italy, with an evaluation of their spatial and temporal distribution. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 16, 2485–2500. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-16-2485-2016 (2016).

Bilasco, S. et al. Flash flood risk assessment and mitigation in digital-era governance using unmanned aerial vehicle and GIS spatial analyses case study: small river basins. Remote Sens. 14, 2481. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14102481 (2022).

Al-Areeq, A. M. et al. Computational machine learning approach for flood susceptibility assessment integrated with remote sensing and GIS techniques from Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Remote Sens. 14, 5515. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14215515 (2022).

Arabameri, A. et al. Flash flood susceptibility modelling using functional tree and hybrid ensemble techniques. J. Hydrol. 587, 125007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125007 (2020).

Pandey, M. et al. Flood susceptibility modeling based on new hybrid intelligence model: optimization of XGboost model using GA metaheuristic algorithm. Adv. Space Res. 69, 3301–3318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2022.02.027 (2022).

Liu, J. F., Liu, K. & Wang, M. A. Residual neural network integrated with a hydrological model for global flood susceptibility mapping based on remote sensing datasets. Remote Sens. 15, 2447. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15092447 (2023).

Gharakhanlou, N. M. & Perez, L. Flood susceptible prediction through the use of geospatial variables and machine learning methods. J. Hydrol. 617, 129121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129121 (2023).

Bettoni, M. et al. Land use effects on surface runoff and soil erosion in a southern Alpine valley. Geoderma 435, 116505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2023.116505 (2023).

Jaafarzadeh, M. S., Tahmasebipour, N., Haghizadeh, A., Pourghasemi, H. R. & Rouhani, H. Groundwater recharge potential zonation using an ensemble of machine learning and bivariate statistical models. Sci. Rep. 11, 5587. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85205-6 (2021).

Riihimäki, H., Kemppinen, J., Kopecky, M. & Luoto, M. Topographic wetness index as a proxy for soil moisture: the importance of flow-routing algorithm and grid resolution. Water Resour. Res. 57, eWR029871. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR029871 (2021).

Bui, Q. T. et al. Verification of novel integrations of swarm intelligence algorithms into deep learning neural network for flood susceptibility mapping. J. Hydrol. 581, 124379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.124379 (2020).

Giovannettone, J., Copenhaver, T., Burns, M. & Choquette, S. A statistical approach to mapping flood susceptibility in the lower connecticut river valley region. Water Resour. Res. 54, 7603–7618. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018wr023018 (2018).

Roy, P. et al. Threats of climate and land use change on future flood susceptibility. J. Clean. Prod. 272, 122757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122757 (2020).

Sedgwick, P. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. BMJ 349, 748. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7528 (2014).

Khuri, A. I. Introduction to linear regression analysis. Int. Stat. Rev. 81, 318–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/insr.12020_10 (2013).

LeDell, E. & Poirier, S. H2O automl: Scalable automatic machine learning. In Proceedings of the AutoML Workshop at ICML (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Toward an improved ensemble of multi-source daily precipitation via joint machine learning classification and regression. Atmos. Res. 304, 107385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2024.107385 (2024).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S. I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neur Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 475 (2017).

Tang, X. Z., Li, J. F., Liu, M. N., Liu, W. & Hong, H. Y. Flood susceptibility assessment based on a novel random Naive Bayes method: a comparison between different factor discretization methods. Catena 190, 104536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2020.104536 (2020).

Ma, M. H. et al. XGBoost-based method for flash flood risk assessment. J. Hydrol. 598, 126382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126382 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) Program of China (Grant Nos. 2019QZKK0903,2019QZKK0403) and project of National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFF0801804).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. L conceptualized the study. F. H drafted the literature review, developed the methodology, and interpreted the results. S. L, X. M, and Z. W reviewed and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors have given consent for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, F., Liu, S., Mo, X. et al. Interpretable flash flood susceptibility mapping in Yarlung Tsangpo River Basin using H2O Auto-ML. Sci Rep 15, 1702 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84655-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84655-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Machine learning model optimization for flood susceptibility zonation over the Kosi megafan, Himalayan foreland basin, India

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Uncovering Spatiotemporal Urban Flood Dynamics: An Explainable GeoAI Approach to Land Cover Change Over Two Decades

Earth Systems and Environment (2025)

-

Multi-dimensional assessment of flood susceptibility drivers in the urban watershed of Guwahati

Acta Geophysica (2025)

-

Analysis of a comprehensive inventory of rainfall-induced landslides and multi-factor coupling mechanisms in Eastern Guangdong, China, in August 2018

Environmental Earth Sciences (2025)

-

Interpretable machine learning for flood susceptibility mapping in the metropolitan region of São Paulo, Southeast Brazil

Discover Geoscience (2025)