Abstract

Enhancement of security, personalization, and safety in advanced transportation systems depends on driver identification. In this context, this work suggests a new method to find drivers by means of a Random Forest model optimized using the osprey optimization algorithm (OOA) for feature selection and the salp swarm optimization (SSO) for hyperparameter tuning based on driving behavior. The proposed model achieves an accuracy of 92%, a precision of 91%, a recall of 93%, and an F1-score of 92%, significantly outperforming traditional machine learning models such as XGBoost, CatBoost, and Support Vector Machines. These findings show how strong and successful our improved method is in precisely spotting drivers, thereby providing a useful instrument for safe and quick transportation systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Driver identification is increasingly recognized as a critical component within advanced transportation systems. Driver identification systems help to provide a variety of necessary capabilities for contemporary transportation, including tailored vehicle settings, greater safety procedures, and more operational efficiency.

Driver identification mostly helps to maximize operational efficiency and resource allocation by means of its function in Automated systems may, for example, maximize the distribution of drivers to cars depending on several criteria like availability and rest needs, therefore lowering idle time and needless delays in the transportation system1,2. In industries like rail goods, where prompt delivery is critical, this optimization increases production and guarantees that drivers are regularly engaged in their jobs. Furthermore, the recognition of distinctive driving habits may guide the creation of customized features in cars, therefore improving the driving experience generally3.

Furthermore, driver identification has significant safety consequences. Modern identification technologies-such as those using biometric data and machine learning algorithms-can track driver states and behaviors, spotting circumstances like attention or tiredness4,5. Systems that examine facial characteristics and driving habits, for instance, may send alerts or interventions when a driver is judged to be in a compromised condition, therefore averting possible accidents. The application of deep learning models to identify driver states emphasizes even more the need for driver identification in improving road safety6,7.

Regarding commercial uses, fleet management and usage-based insurance models depend on driver identification. Companies may customize insurance rates depending on real driving behavior by precisely identifying drivers and tracking their activities via many sensors, therefore encouraging safer driving practices8,9,10. Moreover, tracking many drivers running the same vehicle may greatly affect operational strategies in public transportation and logistics, thus guaranteeing responsibility and improving service delivery11.

The growing usage of smartphones and other wearable devices as sensor platforms reflects the technical developments in driver identification as well. These devices may gather information on driving behavior, which can then be used to identify certain drivers precisely using machine learning approaches. This method simplifies the identification procedure and connects perfectly with current transportation management systems, improving their efficiency12,13.

Ultimately, advanced transportation systems are fundamentally based on driver identification, which helps to improve safety, operational effectiveness, and individual user experiences. The integration of advanced identification systems will be very important in determining the direction of transportation as technologies keep developing.

Research gap

Despite significant advancements in driver identification systems for intelligent transportation, most existing methods rely on traditional machine learning models without leveraging optimization algorithms for feature selection and hyperparameter tuning. These approaches often face challenges such as suboptimal model performance, lack of generalizability across datasets, and computational inefficiencies.

Feature selection and hyperparameter tuning are critical to enhancing model accuracy, robustness, and scalability. However, many state-of-the-art methods fail to systematically integrate optimization techniques, resulting in models that are either overfitted to specific datasets or unable to achieve the desired balance between accuracy and computational cost. Furthermore, the absence of advanced optimization algorithms limits the ability of these models to fully exploit relevant patterns in driving behavior data.

Contribution

In this work, we proposed driver identification system using Salp Swarm Optimization (SSO) for hyperparameter tuning of a Random Forest model and the Osprey Optimization Algorithm (OOA) for feature selection. By optimizing both feature selection and model parameters, our method greatly improves the identification accuracy and results better performance than conventional techniques. By means of its strong and effective solution for driver behavior detection, the integration of these sophisticated optimization strategies helps to create safer and more secure modern transportation systems.

Objective

-

Propose a model leveraging driving behavior patterns to accurately identify drivers in advanced transportation systems.

-

Utilize the Osprey Optimization Algorithm (OOA) for feature selection and Salp Swarm Optimization (SSO) for hyperparameter tuning to enhance the performance of the Random Forest model.

-

Improve critical performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score compared to conventional machine learning methods like XGBoost, CatBoost, and Support Vector Machines.

-

Apply the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) to address class imbalances and ensure the reliability of the model’s performance.

-

Perform statistical and correlation analyses to demonstrate the effectiveness and generalizability of the proposed approach for real-world applications.

-

Provide a scalable and efficient solution for safer, more secure, and personalized transportation.

Organization

The rest of the paper is organized as follows, related work is presented in section 2. Details of proposed approach is presented in section 3. Simulated results are presented in section 4. Finally, section 5, concluded the paper.

Related work

Supraja et al.14 proposed a CNN-based model for detecting distracted driving and establishing an alert system that warns the driver by sending a text message to the owner using Twilio SMS API. The model utilizes a fine-tuned VGG16 pre-trained on various classes of distractions observed among drivers. The model’s significant limitation is its reliance on pre-labeled data on distractions, which might not cover all real-world scenarios and distractions, potentially reducing its effectiveness in varied conditions. Additionally, the reliance on SMS for alerts may introduce delays and depend on cellular network availability.

Stankovic et al.15 introduces an enhanced Sand Cat Swarm Optimization (SCSO) algorithm tailored for feature selection and hyper-parameter optimization of an Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) model. The framework aims to improve diabetes diagnostics, addressing NP-hard challenges with a focus on selecting relevant features and optimizing ELM parameters for better classification performance on a diabetes dataset.

Saleh et al.16 proposed an integrated system that combines 5G technologies, Software-Defined Networks (SDN), and deep learning to enhance the safety of autonomous vehicles. The system detects drowsy drivers using a deep-learning-based technique deployed at the edge, reducing the likelihood of accidents and road congestion. The SDN is utilized for network slicing to ensure the required Quality of Service (QoS) for control delegation to the remote control center (RCC). However, the model’s limitations include its dependency on reliable 5G network infrastructure and the complexity of integrating SDN for real-time applications. The system’s effectiveness is constrained by the performance of the underlying communication technologies, which may not be consistent in all environments.

Zivkovic et al.17 presents a hybrid framework combining a simple Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and an XGBoost classifier, optimized using a hybrid Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (AOA), for automated analysis of chest X-ray images to detect COVID-19. The proposed method achieves a high classification accuracy of 99.39% and outperforms other state-of-the-art methods, validating its effectiveness using a balanced dataset of 12,000 X-ray images.

Mamoudan et al.18 propose a hybrid framework combining particle swarm optimization (PSO) for feature selection and a hybrid CNN-GRU model optimized with a genetic algorithm (GA) for predicting water consumption in agricultural supply chains. The results are incorporated into a multi-objective optimization model to balance profitability and sustainability by addressing water usage, environmental pollutants, food and production waste, and costs. A real-world case study in Iran validates the framework, offering practical insights for sustainable agricultural supply chain management.

Dakic et al.19 addresses cyber-security challenges in controller area network (CAN) systems within automotive vehicles by proposing a machine learning-based intrusion detection framework. It employs Extreme Gradient Boost (XGBoost) and K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) classifiers, optimized through a modified metaheuristic optimizer. The approach achieves over 89% accuracy on a public dataset, with feature impacts analyzed using explainable artificial intelligence techniques.

Zhou et al.20 addresses the critical challenge of security in VANETs under 6G communication systems by proposing a hybrid approach that combines identity-based encryption for secure vehicle authentication and deep learning techniques for detecting malicious packets, achieving an impressive accuracy of 99.72%.

Hanafi et al.21 proposed a real-time, operating system-agnostic distracted driver monitoring engine using deep learning, addressing the limitations of expensive hardware-based systems that are unaffordable for low- and middle-income countries. The system leverages smartphones, which are accessible and widely used, to detect drowsiness and generate alerts, employing machine learning for detection, feature extraction, and image classification. However, the model’s limitations include potential platform-specific performance variability and challenges with intermittent detection reliability due to variations in smartphone hardware capabilities and environmental conditions.

Zhou et al.22 propose a novel GAN-Siamese network for vehicle re-identification (Re-ID) across challenging cross-domain scenarios, such as day-time and night-time environments. The approach uses a GAN-based domain transformer and a four-branch Siamese network to enhance domain adaptation and achieve state-of-the-art performance on multiple large-scale datasets.

Vijayakumar et al.23 introduce a passive-awake cloud-cluster communication system designed to optimize power consumption in energy-constrained electric vehicles (e-vehicles). By addressing energy degradation in wireless transmission, the proposed system extends the operational lifetime of e-vehicles in intelligent transportation systems.

Jeong et al.24 proposed a driver identification system using deep learning technology with Controller Area Network (CAN) data collected from vehicle sensors that capture driver characteristics. The system utilizes a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) alongside techniques such as 1D CNN, normalization, special section extraction, and post-processing to enhance identification accuracy. The proposed system achieved an average accuracy of 90% in experiments involving four drivers. However, the model’s limitations include relatively slow convergence time, as it takes 4-5 minutes to reach 80% accuracy in real-time scenarios, which may not be suitable for immediate driver identification needs.

Sharma et al.25 propose a misbehavior detection framework for heterogeneous-vehicular collaboration in the Internet of Vehicles (IoVs). The scheme employs three phases-context procurement, sharing, and detection-to identify and mitigate Sybil attacks and false message generation attacks, achieving high detection rates of 99% and 98.5%, respectively.

Gupta et al.26 introduce a novel deep learning-based approach for driver behavior detection, focusing on identifying critical behaviors such as eye closure, yawning, and inattentiveness within the Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) framework. It achieves a high accuracy of 94%, demonstrating the potential for real-time monitoring in Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS). Gupta et al.27 presents a hybrid approach combining lightweight cryptography and graph-based machine learning to address authentication and security challenges in Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS). It focuses on detecting malicious nodes and mitigating cyber threats while ensuring efficient identity-based authentication for smart vehicles.

Ravi et al.28 proposed an optimized deep learning model using Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks for driver identification based on driving behavior data captured by sensors. The model addresses security vulnerabilities in Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) by identifying drivers through unique driving styles, reducing computational power compared to face recognition methods. The key contribution is the inclusion of hyperparameter tuning using a nature-inspired optimization algorithm to enhance model performance. However, the model’s limitations include the dependency on accurate sensor data, which may be prone to noise or inaccuracies, potentially affecting identification accuracy. Additionally, the approach may not perform well in scenarios with highly similar driving patterns among different drivers.

Proposed approach

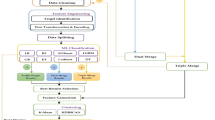

This section presents the details of the proposed approach. Figure 1 presents utilizing optimal Random Forest the suggested model for driver identification in modern transportation systems. The procedure starts with the database storing of driver driving patterns gathered. Data preparation is the process of utilizing SMote to clean and balance the data therefore guaranteeing a balanced dataset. The Osprey optimization algorithm (OOA) then uses the preprocessed data to find the most important characteristics by assessing the fitness of several feature sets. Training and testing sets include the chosen features; the Random Forest model is trained using the training data. salp swarm optimization (SSO) allows one to fine-tune the Random Forest model’s hyperparameters. The SSO continuously changes the local and global best solutions, therefore improving the performance of the model. At last, the trained model produces output forecasts proving the success of the suggested method.

Data prepossessing

Data collection

The data collection process can be represented as:

where D is the collected dataset. \(x_i\) represents the feature vector for the i-th sample (driver’s driving pattern data). \(y_i\) is the corresponding label or target variable (driver identification). N is the total number of samples collected.

Data cleaning

Data cleaning involves removing or imputing missing values and filtering outliers. Let \(D_{clean}\) be the cleaned dataset:

where m is the number of features. The condition ensures that each feature vector \(x_i\) is free from missing values or outliers.

SMOTE operation for data balancing

Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) generates synthetic samples to balance the classes. The SMOTE operation can be mathematically described as follows:

For each minority class sample \(x_i\), a new synthetic sample \(x_{syn}\) is generated using its k-nearest neighbors (\(NN_k\)):

where \(x_{syn}\) is the synthetic sample generated. \(x_{NN}\) is a randomly selected neighbor of \(x_i\) from its k-nearest neighbors. \(\delta\) is a random number between 0 and 1 (\(\delta \sim U(0, 1)\)), introducing variability.

The final balanced dataset \(D_{balanced}\) combines the original cleaned data \(D_{clean}\) and the synthetic samples generated:

where M is the number of synthetic samples generated.

Feature selection using osprey optimization algorithm (OOA)

This section explains the working of the OOA process for feature selection .

Initialization phase

Set the population size N and the total number of iterations T. Initialize the population of solutions \({\textbf{X}} = \{X_1, X_2, \ldots , X_N\}\).

Fitness evaluation

Evaluate the initial population based on a fitness function F:

Iteration process (repeat until convergence or maximum iterations reached)

Set iteration \(t = 1\).

-

Phase 1: Update Fitness Probability (FP) Update the fitness probability of each osprey based on its fitness value:

$$\begin{aligned} FP_i = \frac{F_i}{\sum _{j=1}^{N} F_j}, \quad \forall i = 1, 2, \ldots , N \end{aligned}$$(7) -

Phase 1.1: Select Fish and Update Osprey Position Determine the selected fish SF by the i-th osprey at random.

Calculate the new position of the i-th osprey using:

$$\begin{aligned} X_i^{t+1} = X_i^t + r_1 \cdot (X_{SF} - X_i^t) \end{aligned}$$(8)where \(r_1\) is a random number between 0 and 1. \(X_{SF}\) is the selected fish position. Update the osprey’s position:

$$\begin{aligned} X_i^{t+1} = X_i^t + r_2 \cdot (X_{best} - X_i^t) \end{aligned}$$(9)where \(r_2\) is another random number between 0 and 1. \(X_{best}\) is the current best solution in the population.

-

Phase 2: Update Position for Exploitation Calculate the new position using another rule based on the exploitation phase:

$$\begin{aligned} X_i^{t+1} = X_i^t + r_3 \cdot (X_{best} - X_i^t + \epsilon ) \end{aligned}$$(10)where \(r_3\) is a random coefficient controlling exploitation. \(\epsilon\) is a small perturbation factor.

Termination check

Check if the iteration count t reaches the maximum T. If not, update the best solution:

Set \(t = t + 1\) and repeat until \(t = T\).

Output the best solution

Once the termination condition is met, output the best candidate solution found:

Hyper-parameters SSO

The SSO algorithm is used for optimizing the hyperparameters of the Random Forest model. The following equations describe the SSO process based on the provided flowchart.

Initialization phase

Initialize the Salp population \({\textbf{X}} = \{X_1, X_2, \ldots , X_N\}\), where each \(X_i\) represents a potential solution (set of hyperparameters) for the Random Forest model.

Fitness evaluation

Calculate the fitness value for each salp using a fitness function F, which evaluates the performance of the Random Forest model based on the current hyperparameters:

Sorting and identifying the best salp (food position)

Sort the fitness values in ascending order to find the best fitness (food position):

Set the food position and food fitness:

Update the iteration parameter

Update the iteration parameter based on the current step of the algorithm.

Update the position of the leading salp

The position of the leading salp (first salp in the sorted list) is updated using:

where \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are random numbers between 0 and 1 that control exploration and exploitation.

Update the position of the follower salps

Update the position of the follower salps using Newton’s law of motion, simulating the movement of follower salps based on the leading salp:

Boundary check

Ensure the updated positions are within the defined search space:

where \(X_{\text {upper}}\) and \(X_{\text {lower}}\) are the upper and lower bounds of the search space.

Stopping condition

Check if the stopping condition is met (maximum iterations or convergence criteria):

Return the best solution

Output the best solution (best hyperparameters for the Random Forest):

Results and discussion

System information

The simulation setup for this study was conducted on a Windows 10 system with an Intel64 Family 6 Model 151 processor (6 physical and 12 logical cores), 16 GB of RAM (8.7 GB available during simulations), and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050 GPU with 8 GB memory, although the GPU was not utilized as computations were CPU-based. The software environment included Python 3.11.5 (Anaconda), PyTorch 2.2.1, Pandas 1.5.3, NumPy 1.24.3, scikit-learn 1.4.1.post1.

Dataset prepossessing

This work utilizes a Kaggle dataset created to identify various driving actions and extract driver patterns using the Carla Simulator platform. Using a “Seat Leon” vehicle, the data was gathered with a 6-axis virtual IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit), comprising a 3-axis accelerometer and a 3-axis gyroscope, so capturing the driving behavior of seven different drivers (mehdi, apo, gonca, onder, berk, selin, and hurcan) as they navigated a specific path on the “Town03” map. Following the same road with five twists, every driver helped to contribute to the goal class-that which reflects their driver name.

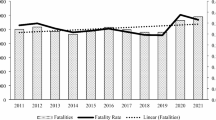

The target classes in the dataset are distributed as shown in Fig. 2a. The result shows that, followed by “onder” (15,708) and “apo” (13,738), the driver “selin” had the most driving instances-18,982. With frequencies of 13,192, 12,904, 12,614, and 12,220 occurrences respectively, the drivers “berk,” “gonca,” “hurcan,” and “mehdi” also made somewhat significant contributions. This distribution emphasizes the fluctuation in the dataset and suggests that the model has to efficiently manage imbalanced class data for correct driver identification.

The Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) was used to correct the disparity seen in the original dataset (Fig. 2a). By guaranteeing that every class has a same number of occurrences, SMote is a potent resampling technique that creates synthetic samples for the minority classes thereby balancing the dataset.

Figure 2b show the dataset’s distribution after SMote application. As seen, with each class having about the same frequency of around 17,500 instances, the instances for all driver classes are now equally distributed. This balanced dataset offers the model a fair training environment, hence improving its capacity to generalize across several driving patterns without biassed favoring of any one driver.

Performance of osprey optimization algorithm (OOA)

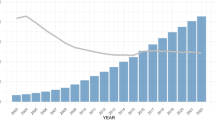

The most relevant characteristics from the dataset were found using the Osprey Optimization Algorithm (OOA)29,30, therefore enhancing the performance of the model. Run for 100 epochs with a population size of 50, the optimizer shows performance in the figures below.

Figure 3a shows OOA running throughout iterations with oscillations as the algorithm advances. Usually rising throughout the first iterations, the runtime peaked around the fourth iteration before settling at one hundred seconds each iteration. This suggests that as the algorithm searches the search space before settling into a more regular pattern, the computing cost first increases.

Figure 3b shows the variety of ideas found in the population. Initially declining diversity indicates fast convergence in the early rounds; then, as the algorithm balances exploration and exploitation, stability results. Peaks around the middle iterations point to OOA attempts at periodic diversification meant to prevent local optima.

Exploration and exploitation dynamics throughout the iterations are shown in Fig. 3c. Starting with a large exploration percentage, the algorithm progressively reduces while exploitation rises to indicate that OOA starts by extensively searching the search space then moves towards improving the best answers.

Following the Osprey Optimization Algorithm (OOA) to identify the most significant characteristics, a correlation matrix was used to examine the correlations between these particular features and the objective variable-which stands for several drivers-class. Examining how characteristics interact with one another and how their combined influence the categorization process depends critically on the correlation matrix. It helps one understand which traits are unique in their contributions or which could be repeated in response to strong relationships.

Figure 4 shows the correlation coefficients between the major features-including accelerometer measurements along the X, Y, and Z axes (accelX, accelY, accelZ) and gyroscope readings (gyroX, gyroZ). Given that every feature is exactly linked with itself, the diagonal elements exhibit the predicted perfect correlation of 1. More significantly, the off-diagonal components draw attention to the interactions across many feature pairs. For example, accelY and gyroZ show a really significant positive correlation (0.68), suggesting a coordinated pattern in their variances. This implies that associated elements of the driver’s behavior may be captured by these characteristics, which would be essential to differentiate between various driving techniques.

The positive correlation (0.38) shown by accelX and accelY also indicates that the lateral (Y-axis) and longitudinal (X-axis) accelerations are somewhat correlated, most likely owing to the driving dynamics while negotiating curve or speed changes. Other characteristics, including accelZ and the gyroscope readings, show significantly less connection with each other and the target variable, thus showing their more independent contributions to the categorization work.

The intricacy of the driver identification issue is shown by the target variable (class), which shows usually poor correlation values with individual characteristics. This poor correlation implies that no one characteristic mostly predicts the class, hence an integrated method using the combined effect of many variables is necessary to provide reliable driver identification. This study clarifies the feature set and confirms the need of strong machine learning methods to identify relevant trends from these intricate interactions.

Performance of salp swarm optimization (SSO)

The Salp Swarm Optimization (SSO)31 was used to fine-tune the hyperparameters of the Random Forest model after the identification of the most significant features by the Osprey Optimization Algorithm. The following figures show the SSO algorithm’s performance all through its optimization phase.

Over ten iterations, the SSO algorithm’s runtime is shown in Fig. 5a. Starting at around 400 seconds and culminating at about 600 seconds, the duration steadily rises as the iterations go forward. As the SSO repeatedly searches the hyperparameter space investigated for the Random Forest model, this increase in runtime represents the growing complexity of that space. Achieving high-quality optimization depends on SSO fully probing the search space, as the consistent rise suggests.

Figure 5b (Diverse Measurement Chart) shows the variation of the population within the SSO algorithm. Diversity first rises around the second iteration, signifying a large exploration phase in which the method explores broadly throughout the parameter space. The variety rapidly declines as iterations go on, indicating that the algorithm is narrowing down on the best answers and lowering pointless fluctuations. Typical in optimization procedures as the algorithm moves from exploration to exploitation is a drop in variety.

Percentage of Exploration vs. Exploitation During the optimization process is show n in Fig. 5c. Early on, exploration rules because the high percentage values let the SSO examine a large spectrum of hyperparameter possibilities. Reflecting the algorithm’s movement toward fine-tuning the found potential solutions, exploration declines while exploitation rises as the iterations progress. By means of the last iterations, the SSO efficiently balances both approaches, thus guaranteeing complete hyperparameter optimization to maximize the performance of the Random Forest model.

Performance analysis of proposed model

Driver identification is a complex task requiring models to effectively distinguish between subtle variations in driving behaviors across multiple individuals. The proposed Random Forest model improves classification performance by using cutting-edge optimization methods. The confusion matrix shown in Fig. 6 offers a comprehensive perspective of the classification results of the model over seven different driver classes (labeled 0–6), therefore helping one to assess its efficacy. By use of proper and erroneous classifications, this study emphasizes the strengths and areas for development of the model.

The model shows good general performance; high values along the confusion matrix’s diagonal indicate correct classifications for most classes. Class 0, for example, scored 1,700 accurate predictions, therefore demonstrating the model’s capacity to identify unique characteristics for this group. With 3,101 cases, Class 6 also noted the highest number of accurate classifications, therefore highlighting its strength in spotting some driver actions. These findings show how well the hyperparameter tuning and feature selection techniques enable the model get high accuracy for well-defined classes.

Though it has certain advantages, the matrix also shows clear misclassifications for several groups. Class 5, for instance, shows uncertainty with Class 4 (210 cases) and Class 6 (420 cases), implying either overlapping behavioral patterns or feature similarities. Likewise, Class 1 is sometimes misclassified as Class 0 (150 cases) and Class 2 (110 cases), suggesting possible places where feature separability might be enhanced. These misclassifications underline the difficulties caused by closely related driving behaviors, therefore stressing the need of further improvement of the feature engineering and optimization techniques.

Examining trends particular to each class offers still another perspective on the behavior of the model. With both the biggest number of accurate classifications and rather low misclassification rates, Class 6 turns up as the top performing class. By contrast, Class 5 and Class 4 show higher misclassification rates, implying that the model finds it difficult to accurately separate these classes. Future research could address these difficulties by including more data or improving feature selection to more effectively capture minute driving style variances.

Also, in Fig. 7, the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for the proposed Random Forest model show the trade-off between the True Positive Rate (TPR) and False Positive Rate (FPR) for every one of the seven classes (0-6). Furthermore shown in the legend are the Area Under the Curve (AUC) values, which measure the general model performance for every class.

With AUC values ranging from 0.9156 (Class 3) to 0.9488 (Class 6), the ROC curves expose robust classification performance across all classes. These strong AUC values show that for every class the model efficiently separates positive from negative examples. With an AUC of 0.9488, Class 6 performs the best indicating the great sensitivity and specificity of the model for this class. With corresponding AUC values of 0.9299 and 0.9272, Class 2 and Class 4 likewise show strong performance.

The AUC values for the remaining classes still demonstrate consistent performance across all driver categories, exceeding 0.91. For most classes, the ROC curves’ proximity to the top-left corner especially supports the model’s capacity to minimize false positives while preserving high true positive rates.

The minor differences in AUC values among classes draw attention to possible areas for development, including increasing feature separability for Class 3, whose AUC of 0.9156 is lowest. Still, the always high AUC values across all classes confirm the potency of the suggested Random Forest model and its optimizing methods.

Comparative analysis

The Random Forest model was trained and evaluated on the balanced dataset using salp swarm optimization (SSO) hyperparameter tweaking. Several alternative machine learning models, including XGBoost, Catboost, Naive Bayes, K-Nearest Neighbors, AdaBoost, Gradient Boosting, Logistic Regression, and Support Vector Machine (SVM), were examined against the suggested method. The findings show our suggested approach’s superiority as shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8a contrasts the precision of our suggested method with other models. At 0.66, the suggested method attained the best accuracy among all other models, far above While K-Nearest Neighbors attained 0.50058, XGBoost and Catboost respectively attained accuracies of 0.37641 and 0.37802. Other models, including Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression, and SVM, showed much lower accuracies, thereby underlining the robustness of our suggested method in precisely identifying drivers depending on their driving behavior.

Figure 8b the suggested approach’s recall is likewise the greatest. Recall Comparison Superior recall shown by the proposed model indicates its efficiency in accurately spotting the positive instances-drivers-within the data. Minizing misclassifications depends on this great recall, especially in safety-critical uses like driver identification in transportation systems.

Figure 8c suggested method has also shown leading accuracy. High precision implies that the model is precise in its positive forecasts, hence lowering the false positive incidence. This great accuracy guarantees dependability in the predictions of the model, which is essential for useful applications in transportation systems where inaccurate driver identification could cause operational problems.

The F1-score (Fig. 8d), which strikes a mix between recall and accuracy, supports even more the power of our suggested method. With the best F1-score, the suggested approach shows a well-balanced performance between minimising false positives and appropriately spotting real positives. Other models did not perform as regularly across both measures, even if they attained modest accuracy or recall separately.

The results taken together show the better performance of our suggested method over conventional machine learning models. The findings confirm the effectiveness of our improved Random Forest model, particularly in view of OOA and SSO methods for hyperparameter tweaking and feature selection.

The ROC curve comparison shown in Fig. 9 shows the performance of several models applied in this work. For every model, the ROC curve graphs the True Positive Rate (TPR) versus the False Positive Rate (FPR), therefore offering a whole assessment of their capacity to differentiate across driver types. This performance is measured using the Area Under the Curve (AUC) metric; greater AUC values suggest improved general classification capacity.

With an AUC of 0.9214, the proposed approach-random forest-achieves the best performance. Reflecting a high true positive rate and a low false positive rate throughout many classification criteria, its ROC curve is closest to the top-left corner. This better performance shows the success of the used optimization methods, Salp Swarm Optimization for hyperparameter tweaking and Osprey Optimization Algorithm for feature selection. These improvements clearly help the model to detect driver behaviors with great accuracy and dependability.

Competitive performance also comes from K-Nearest Neighbors (AUC = 0.8274) and CatBoost (AUC = 0.7691) among the baseline models. Although their ROC curves indicate respectable classification abilities, the difference in AUC values between their approach and the proposed one emphasizes the benefits of including cutting-edge optimization strategies. Other models, such as Gradient Boosting (AUC = 0.7045) and XGBoost (AUC = 0.7625), perform moderately well but are clearly outperformed by the proposed approach in terms of both AUC and ROC curve positioning.

In contrast, models like Logistic Regression (AUC = 0.5556) and Naive Bayes (AUC = 0.5582) perform poorly, with ROC curves that closely follow the diagonal line, which represents random classification. This implies that since these models cannot successfully differentiate between the minute changes in driving behavior, they are not suited for the complexity of driver identification activities.

The box plot shown in Fig. 10 offers a thorough picture of the performance measure distribution-accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 Score-across the assessed machine learning systems. This study provides important new perspectives on the relative strengths and shortcomings of the suggested and baseline models, therefore helping to explain their consistency and variability.

With the median score close to the lower range of the interquartile range (IQR), the accuracy metric indicates rather fluctuation. This suggests that certain models perform noticeably better or worse even if most of them reach similar accuracy. Precision likewise shows a similar distribution pattern, with an upper end outlier. This outlier shows that one model-probably the suggested Random Forest or another optimal model-achieved considerably higher precision than the others. The larger IQR for both measures draws attention to some degree of discrepancy among the models’ capacity to appropriately identify events.

By comparison, the Recall metric shows a smaller distribution, suggesting more consistency over the models. Slightly more than accuracy and precision, the median recall indicates that the models recognize real positive events relative to their general projections. This stability shows that recollection is less vulnerable to model-specific variability, hence a good performance measure for driver identification.

Like accuracy, the F1 Score strikes a mix of precision and recall that displays variability. Reflecting an overall balanced performance of the models in terms of both true positives and false positives, the median F1 score is rather higher than the accuracy and precision medians. The larger IQR and range of values, however, point to some models’ difficulty striking a compromise between recall and precision.

Conclusion

This work presents a driver detection method employing an optimal Random Forest model in modern transportation systems. The suggested approach proved better than conventional machine learning models like XGBoost, Catboost, and SVM by using the Osprey Optimization Algorithm (OOA) for feature selection and the Salp Swarm Optimization (SSO) for hyperparameter tuning. Validating its ability in separating drivers depending on their driving behaviors, the model attained the greatest accuracy (0.66), recall, precision, and F1-score. The balanced dataset produced by SMote and examined using a correlation matrix improved the resilience of the model yet further. These results highlight the possibility of the suggested method to enhance driver identification, therefore supporting the security and customization of modern transportation systems. However, the proposed approach, while achieving significant improvements in driver identification, is computationally intensive due to the integration of dual optimization algorithms and may face scalability challenges with larger datasets or real-time applications. Additionally, its performance may vary across different driving datasets, requiring further validation in diverse real-world scenarios. In this context, future work will focus on optimizing the computational efficiency of the proposed framework to enhance scalability for larger datasets and real-time applications. Additionally, we aim to validate and adapt the approach to diverse driving datasets to ensure broader applicability and robustness.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Kaggle repository, https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/dasmehdixtr/carla-driver-behaviour-dataset/data

References

Brezulianu, A. Artificial intelligence component of the FERODATA AI engine to optimize the assignment of rail freight locomotive drivers. Appl. Sci. 13, 11516. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132011516 (2023).

Vijayakumar, P. et al. Deep reinforcement learning-based pedestrian and independent vehicle safety fortification using intelligent perception. Int. J. Softw. Sci. Comput. Intell. (IJSSCI) 14, 1–33 (2022).

Marchegiani, L. & Posner, I. Long-term driving behaviour modelling for driver identification. In 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), 913–919 (IEEE, 2018).

Lin, N. et al. An overview on study of identification of driver behavior characteristics for automotive control. Math. Probl. Eng. 1–15, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/569109 (2014).

Díaz-Santos, S. Driver identification and detection of drowsiness while driving. Appl. Sci. 14, 2603. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14062603 (2024).

Li, Y., Sun, C. & Hu, Y. Whale optimization algorithm-based deep learning model for driver identification in intelligent transport systems. Comput. Mater. Contin. 75, 3497–3515. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2023.035878 (2023).

Srivastava, A. M., Rotte, P. A., Jain, A. & Prakash, S. Handling data scarcity through data augmentation in training of deep neural networks for 3d data processing. Int. J. Semant. Web Inf. Syst. (IJSWIS) 18, 1–16 (2022).

Ahmadian, R., Ghatee, M. & Wahlström, J. Discrete wavelet transform for generative adversarial network to identify drivers using gyroscope and accelerometer sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 6879–6886. https://doi.org/10.1109/jsen.2022.3152518 (2022).

Chowdhury, A., Chakravarty, T., Ghose, A., Banerjee, T. & Balamuralidhar, P. Investigations on driver unique identification from smartphone’s GPS data alone. J. Adv. Transp. 1–11, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9702730 (2018).

Li, S. et al. False alert detection based on deep learning and machine learning. Int. J. Semant. Web Inf. Syst. (IJSWIS) 18, 1–21 (2022).

Virojboonkiate, N., Chanakitkarnchok, A., Vateekul, P. & Rojviboonchai, K. Public transport driver identification system using histogram of acceleration data. J. Adv. Transp. 1–15, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6372597 (2019).

Wazir, H. It tools evaluation in drivers’ monitoring: A data envelopment analysis (DEA) approach. AMCI 12, 61–71. https://doi.org/10.58915/amci.v12i3.318 (2023).

Stylianou, N., Vlachava, D., Konstantinidis, I., Bassiliades, N. & Peristeras, V. Doc2kg: Transforming document repositories to knowledge graphs. Int. J. Semant. Web Inf. Syst. (IJSWIS) 18, 1–20 (2022).

Supraja, P., Revati, P., Ram, K. & C., J. An intelligent driver monitoring system. In 2021 2nd International Conference on Communication, Computing and Industry 4.0 (C2I4)[SPACE]https://doi.org/10.1109/C2I454156.2021.9689295 (2021).

Stankovic, M. et al. Feature selection and extreme learning machine tuning by hybrid sand cat optimization algorithm for diabetes classification. In International Conference on Modelling and Development of Intelligent Systems, 188–203 (Springer, 2022).

Saleh, S. N. & Fathy, C. A novel deep-learning model for remote driver monitoring in SDN-based internet of autonomous vehicles using 5g technologies. Appl. Sci. 13, 875 (2023).

Zivkovic, M. et al. Hybrid CNN and XGBoost model tuned by modified arithmetic optimization algorithm for covid-19 early diagnostics from x-ray images. Electronics 11, 3798 (2022).

Mamoudan, M. M., Jafari, A., Mohammadnazari, Z., Nasiri, M. M. & Yazdani, M. Hybrid machine learning-metaheuristic model for sustainable agri-food production and supply chain planning under water scarcity. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 14, 100133 (2023).

Dakic, P. et al. Intrusion detection using metaheuristic optimization within IoT/IIoT systems and software of autonomous vehicles. Sci. Rep. 14, 22884 (2024).

Zhou, Z., Gaurav, A., Gupta, B. B., Lytras, M. D. & Razzak, I. A fine-grained access control and security approach for intelligent vehicular transport in 6G communication system. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 9726–9735 (2021).

Hanafi, M. F. F. M. et al. A real time deep learning based driver monitoring system. Int. J. Percept. Cogn. Comput. 7, 79–84 (2021).

Zhou, Z. et al. GAN-Siamese network for cross-domain vehicle re-identification in intelligent transport systems. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 10, 2779–2790 (2022).

Vijayakumar, P., Rajkumar, S. & Deborah, L. J. Passive-awake energy conscious power consumption in smart electric vehicles using cluster type cloud communication. Int. J. Cloud Appl. Comput. (IJCAC) 12, 1–14 (2022).

Jeong, D. et al. Real-time driver identification using vehicular big data and deep learning. In 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITSC.2018.8569452 (2018).

Sharma, R., Sharma, T. P. & Sharma, A. K. Detecting and preventing misbehaving intruders in the internet of vehicles. Int. J. Cloud Appl. Comput. (IJCAC) 12, 1–21 (2022).

Gupta, B. B., Gaurav, A., Chui, K. T. & Arya, V. Deep learning model for driver behavior detection in cyber-physical system-based intelligent transport systems. IEEE Access (2024).

Gupta, B. B., Gaurav, A., Marín, E. C. & Alhalabi, W. Novel graph-based machine learning technique to secure smart vehicles in intelligent transportation systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24, 8483–8491 (2022).

Ravi, C., Tigga, A., Reddy, G. T., Hakak, S. & Alazab, M. Driver identification using optimized deep learning model in smart transportation. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. [SPACE] https://doi.org/10.1145/3412353 (2022).

Dehghani, M. & Trojovskỳ, P. Osprey optimization algorithm: A new bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for solving engineering optimization problems. Front. Mech. Eng. 8, 1126450 (2023).

Zhou, L., Liu, X., Tian, R., Wang, W. & Jin, G. A modified osprey optimization algorithm for solving global optimization and engineering optimization design problems. Symmetry 16, 1173 (2024).

Mirjalili, S. et al. Salp swarm algorithm: A bio-inspired optimizer for engineering design problems. Adv. Eng. Softw. 114, 163–191 (2017).

Acknowledgments

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R343), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA for funding this research work through the project number “NBU-FFR-2025-1092-02”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Final Manuscript Revision, funding, Supervision: B.B.G., K.T.C.; study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of results, methodology development: A.G., V.A., ; data collection, draft manuscript preparation, figure and tables: A.A., R.W.A. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gaurav, A., Gupta, B.B., Attar, R.W. et al. Driver identification in advanced transportation systems using osprey and salp swarm optimized random forest model. Sci Rep 15, 2453 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84710-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84710-8