Abstract

Humans are good at picking up statistical regularities in the environment. Probability cueing paradigms have demonstrated that the location of a target can be predicted based on spatial regularities. This is assumed to rely on flexible spatial priority maps that are influenced by visual context. We investigated whether stimulus features such as color distributions differing in mean and variance can cue location regularities. In experiment 1, participants searched for an oddly colored target diamond in a 6 × 6 set. On each trial, the distractors were drawn from one of two color distributions centered on different color averages. Each distribution was associated with different target location probabilities, one distribution where the target had an 80% chance to appear on the left (the rich location), while the rich location would be on the right for the other distribution. Participants were significantly faster at locating the target when it appeared in the rich location for both distributions, demonstrating learning of the relationship between color average and location probability. In experiments 2 and 3, observers performed a similar search task, but the distributions had different variances with the same average color. There was no evidence that search became faster when the target appeared in a rich location, suggesting that contingencies between target probabilities and color variance were not learned. These results demonstrate how statistical location learning is flexible, with different visual contexts leading to different spatial priority maps, but they also reveal important limits to such learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Imagine you are looking for your cat in the garden. You have noticed that on bright days, she tends to lounge on the lawn, while on cloudy or rainy days, she prefers to stay under the tree. Since the sky is bright today, you instinctively check the lawn first. This simple example illustrates our ability to learn contextual and statistical regularities in the environment and direct our attention to locations where objects of interest are likely to appear in a given context1,2,3,4,5,6.

The last decades of research on visual statistical learning have revealed that we can extract a large amount of information from statistical regularities, often implicitly and unconsciously3. Such effects are evident both in behavioral tasks and neural activity patterns7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 and can be observed when regularities occur in various stimulus features such as orientations16,17, auditory inputs18,19 and more complex stimuli such as written and spoken language20,21,22,23.

A common method for studying the effects of statistical learning on visual attention is the probability cueing paradigm24, where participants typically search for a target among distractors (usually a T among Ls) without prior knowledge about its location probability. Unbeknownst to the participants, the location probability of the target is biased so that it appears more frequently in a specific high-probability “rich” quadrant of the screen (e.g., the top-right part of the screen). Both behavioral and eye-tracking data show that participants quickly develop a search habit biased toward the rich quadrant25,26,27,28,29,30, to the point that the bias persists even when the probabilities are equalized across all quadrants31 (even though the extent of this inflexibility is debated32).

Although these biases tend to persist and are resilient to updating26, there is evidence that humans can flexibly alternate their search strategies between multiple probabilistic representations, likely stored in parallel33,34. Zhang and Carlisle34 found that observers could learn the location probabilities of multiple objects and when they had to find a particular one, they found it faster if it appeared in the expected location. This flexibility is highly useful in daily life, allowing us to search for different objects in different places based on where they are most likely to be found27. It can be hypothesized that statistical learning relies on multiple attentional priority maps — i.e., neural representations that rank different locations or features in the visual field according to their relevance35,36 — that are formed through the combination of templates held in both long-term and short-term memory37 which can be differentially activated depending on the learned association between the features of a target object and its context.

What types of associations support the multiple and parallel statistical learning of attentional priority maps? In classic probability cueing studies, statistical learning is assessed and manipulated by introducing regularities or biases in the location of target stimuli. Learning is therefore primarily dictated by first-order spatial associations — direct relationships between a specific location and the probability of finding a target there. However, learning can also be shaped by more complex associations, such as second-order relationships, where contextual features predict different target locations at different times. For example, varying luminance levels in a search display can be associated with different target location probabilities, leading to statistical learning effects where different priority maps are activated based on the luminance in the current trial33. In this study by Hong et al., two ensembles were shown simultaneously: a black and a white stimulus set. Participants were tasked with finding a target in one or the other, but unbeknownst to them, different spatial probability biases were associated with the two ensembles (e.g., the rich quadrant would be the top-right one for the black ensemble but the bottom-left one for the white ensemble). Nonetheless, observers responded faster if the target appeared in a rich quadrant associated with the target ensemble, but only if the luminance was relevant to the task at hand. However, since Hong et al.33 only examined the predictive properties of uniform black or white ensembles, this leaves unanswered whether other visual information can be used to predict target location.

The distribution of colors often characterizes and distinguishes environments where a target object might be located. For example, when searching for ripe fruit in a garden, ripe fruits are more commonly found among green foliage than among other colors, such as yellow or brown. Similar to other feature distributions38,39,40,41,42, humans can rapidly and efficiently learn statistical properties from color distributions, including the mean, variance, and distribution shape43,44,45,46. Thus, learning these statistical properties may facilitate second-order associations, where color distributions act as predictive cues for the likely target locations.

Investigations of the use of color to influence and guide search have notably been conducted in the domain of contextual cueing47,48. Surprisingly, while the use of color as a marker to distinguish task-relevant and task-irrelevant context is well documented49,50,51,52,53,54, few studies have investigated how color itself can be used as a cue for predicting a target’s location. Kunar et al.55,56 found that repetition of color background speeded target processing but provided little or no visual search guidance, especially when other cues such as spatial layout were provided. Similarly, contextual cueing with real-world images rich in semantic information was unaffected by color changes57 and colored cues led to a contextual cueing effect only when devoid of semantic information58. When considering the stimuli themselves — not their background or any additional cues — only one study, to our knowledge, has investigated how color regularities influence visual search. Huang59 found that repeated color arrangement (a combination of spatial and featural properties) can cue target position, but did not address whether color can, on its own, cue target location. Thus, to date, whether color features can serve as a cue for statistical regularities remains unclear.

The current study

We examined whether statistical properties of color distributions can be used to learn and flexibly exploit the most likely locations of a visual target. To this aim we employed a modified version of the classic probability cuing paradigm where the location probability of the target — a uniquely colored diamond shape — depended on distractor color distributions. In three experiments, we investigated second-order statistical learning effects, testing the predictive properties of average color (Experiment 1) and variance (Experiments 2–3). We focused on these two distribution parameters as they have been shown to be automatically extracted and have an influence on visual search43,45,46.

Experiment 1 – Can the mean of a color distribution serve as a cue for likely target locations?

Method

Participants

Thirty-nine participants (53.85% ♀, 26.46 ± 5.49 years old) recruited at the University of Iceland took part in the experiment, completing a single experimental session of about 45 min, and were rewarded with 1,000 ISK. Participants signed an informed consent briefly describing the experiment and informing them that their data would be processed anonymously and that they were free to end their participation at any moment. After completing the experiment, they received their reward and were debriefed about the goals of the experiment. The experiments were approved by the National Bioethics committee in Iceland (Vísindasiðanefnd, http://vsn.is) and performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Material and procedure

Participants were seated in a dark room, positioned approximately 60 cm from a 27-inch monitor. All participants underwent color blindness screening using the Ishihara test60. No participants were excluded based on this test.

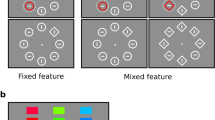

The experimental task was programmed in Python 3.6 61 and executed with Spyder62. Search displays consisted of 36 colored diamonds, each with a randomly selected corner cut off (see Fig. 1). These diamonds were arranged on a 6 × 6 invisible grid with fixed positions, and a small positional jitter of 0.5 degrees of visual angle was applied to the x- and y-coordinates. The overall search display spanned a visual angle range from − 10 to + 10 degrees on both the X and Y axes. The diamond colors were drawn from a color space consisting of 48 isoluminant hues, designed so that each color difference represented approximately 1 group-averaged Just Noticeable Difference (JND)43,63.

Sample search displays from experiment 2a with (a) a low variance distribution and (b) a high variance one, both centered on color value 8. (c) Illustration of the difference in variance of both distributions. Each color on the x-axis is separated by 4 JND. (d) Predicted reaction times from experiment 2a plotted as a function of time-on-task (as trial number) and the predictive property of the target’s location. The colored area around the regression line represents SEM (Standard Error of the Mean), and data points correspond to the binned RT average per 10 trials. (e) Predicted estimates of reaction times plotted as a function of time-on-task (first half vs. second half of the task) and the predictive property of the target’s location from experiment 2a. Error bars correspond to the SEM (Standard Error of the Mean). Reaction times have been converted from log-values using an exponential function.

The main manipulation was that the distractors could be drawn from two color distributions, each with a different target location probability. These distributions were truncated normal distributions with a standard deviation of 3 JND and cut off at 1.5 SD45. The average color values of the two distractor distributions were selected from opposite points on the color wheel, corresponding to a 24 JND difference between them (see Fig. 2).

For the first participant, the initial mean values for the two distributions were set at 0 and 24. With each subsequent participant, the means were increased by 8 JND, so that after 6 participants, the distributions had completed a full rotation on the color wheel. The target color was equiprobably located 4 to 5 JNDs away from the distractor color that was the furthest from the mean of the distribution, either to the left or to the right of the color wheel.

Unbeknownst to participants, the target had an 80% chance of appearing on the left side of the screen for one distribution (Distribution A) and 80% chance of appearing on the right side for the other distribution (Distribution B). We labelled the screen side with the higher probability (80%) as the rich side, and the side with the lower probability (20%) as the scarce side.

Participants performed an odd-one-out search task, in which they were required to find the oddly colored target and indicate the location of its missing corner using the corresponding directional arrow keys as quickly as possible. If participants made a mistake, the word “ERROR” appeared briefly in red in the center of the screen.

Trials were separated by a 1000 ms intertrial interval, during which a fixation cross was presented at the center of the screen. Participants were instructed to focus on this fixation cross to ensure consistent eye position at the start of each trial.

The experiment consisted of 5 blocks of 200 trials, with short breaks between blocks. Each block contained an equal number of trials for each distribution, randomly intermixed, resulting in 500 trials for each distribution. Participants also completed a training task involving 20 trials with color distributions having the same properties as in the main task but with random color and no location bias. Participants were invited to perform the training again or immediately start the experiment.

Analysis methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using R 4.2.2 64. Given that RTs generally decrease nonlinearly over time65,66, we modelled RT changes using a nonlinear approach. Specifically, we examined how RTs changes with time-on-task and predictions of the color distribution about target position. To capture a potential nonlinear trend, we employed an exponential decay model67 described by the following formula:

RTs \((\text{Y})\) are predicted based on three key parameters: (1) Y0: the upper asymptote, representing RTs at the initial trial; (2) Yf: the lower asymptote, representing RTs at infinite trial durations; (3) α: the rate of decay, reflecting the speed at which RTs approach the lower asymptote, with X as the time-on-task variable, here the trial number.

We used the nlme package68 to fit this model, incorporating both fixed and random effects. Specifically, we tested fixed effects of predictability of target position and accounted for random effects of individual participants on the Y0 and Yf parameters. The hierarchical framework was implemented in two stages. We first created a baseline model where we tested the parameters against 0, including random effects to account for between-participant variability. Next, we updated the baseline model with a nested model by introducing a fixed effect representing whether the target appeared on the rich (80% likelihood) or the scarce side of the array (20% likelihood). To optimize the model parameters, we used the getInitial function, which automatically selects initial parameter values based on the formula. This provided starting points for the optimization algorithm to estimate the best-fitting parameters. The initial values for the fixed effects in the nested model were based on estimates from the baseline model.

In addition to the nonlinear modelling, we also applied a mixed linear model to analyze the data, using the lme4 package69 to better highlight potential interactions between predictors, as interaction terms are more straightforward to interpret in the general linear model framework. Additionally, this approach allowed us to treat time-on-task as a categorical factor, to compare effects of target position during the first and second halves of the experiment, using both frequentist and Bayesian indicators.

Our mixed linear model had the following form:

This formula predicts RTs (Y) with time-on-task (X1; a categorical factor comparing the first and second halves of the experiment), predictive property of the target’s position (X2; a categorical factor distinguishing the rich and scarce sides), their interaction (X1 × X2), and the distribution (C; a controlled categorical variable representing the two color distributions, A or B) and participants (P) treated as a random effect. The target was more likely to appear on the left for Distribution A while for Distribution B it was more likely on the right. Including the distribution variable helped control for any side-specific RT effects.

The assumptions of linear regression were evaluated using the performance package70 assessing linearity, homogeneity of variance, influential observations, normality of residuals and normality of random effects. A comparison of model predictions with the observed data indicated that log-transformed RTs provided a better fit than raw RTs, so we applied this transformation in our linear models (see Lo & Andrews, 2015 71 for a discussion on the relevance of this transformation on RTs). Data was not transformed for the non-linear model.

Trials with incorrect responses or RTs longer than 3 s were excluded from analyses. To assess the strength of evidence for or against the null hypothesis, we computed Bayes Factors (BF) in addition to frequentist statistical indicators.

Results

Overall mean accuracy was 96.29% (± 2.6) and average RT was 1098.32 ms (± 364.23). A non-linear regression analysis assessed how reaction times were impacted by time-on-task and target location. First, we fitted a base exponential decay model predicting RTs with time-on-task (Eq. 1). The results indicated that all model parameters differed significantly from zero: the upper asymptote was Y0 = 1230.68 ms (SE = 59.3 ; t(36457) = 20.75, p < .001), the lower asymptote was Yf = 909.93 ms (SE = 26.48 ; t(36457) = 34.36, p < .001), and the rate of decay was α = -5.69 (SE = 0.06 ; t(36457) = -101.01, p < .001).

These results confirm that RTs followed an exponential decay pattern over time. Next, we fitted a nested model by including the predictive property of distribution (rich vs. scarce locations) as a fixed effect. Again, all model parameters were significantly different from zero. The upper asymptote did not differ between rich and scarce locations (Y0 diff = -5.19 ms, SE = 16.37; t(36454) = -0.32, p = .75), but the lower asymptote did (Yf diff = -31.71 ms, SE = 8.83 ; t(36454) = -3.59, p < .001). However, the rate of change did not differ between the two (αdiff = -0.08, SE = 0.07; t(36454) = -1.1, p = .27).

This suggests that RTs for rich and scarce conditions started similarly and decreased at the same rate throughout the task, which is a time-course similar to the one described in previous studies26 despite differences in experimental and statistical designs. However, by the end of the experiment, RTs stabilized at different levels, with participants responding faster when targets appeared in the rich location (Yf Rich = 903.24, SE = 26.57) than the scarce location (Yf Scarce = 934.95, SE = 27.29). In other words, participants’ performance improved over time, with a larger advantage for rich over scarce target locations as the experiment progressed (see Fig. 2).

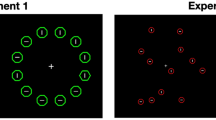

Graphical flow of experiment 1. Target stimuli are circled in red for clarity. The stimulus display was 10° x 10° of visual angle, with each stimulus being 2° by 2°. The participants responded by pressing either the left or right arrow keys. The figure includes an example of a correct response for distribution A (target has a left corner missing) and an incorrect one for distribution B (target has a top corner missing, but the associated response is left). Training could be performed up to two times and participants could rest between each block.

To further assess the interaction between time-on-task and target location, we recoded time-on-task to a categorical factor (first vs. second half of the experiment) and fitted a linear mixed model (Eq. 2). This model explained a substantial portion of the variance (conditional R2 = 0.27), with the fixed effects alone accounting for R2 = 0.02.

The effect of time-on-task was significant and negative (β = -0.11, 95% CI [-0.12, -0.10], t(36455) = -30.03, p < .001), indicating that RTs decreased over time. However, the predictive property of the target location was not significant (β = 0.08− 1, 95% CI [-0.03− 1, 0.02], t(36455) = -1.38, p = .17). Crucially, the interaction between time-on-task and the predictive property was statistically significant and positive (β = 0.02, 95% CI [-0.03− 1, 0.04], t(36455) = 2.39, p < .05).

Marginal contrast analyses revealed no significant difference in average reaction times between rich and scarce locations during the first half of the experiment (x̄diff = -0.08−1, 95% CI [-0.02, 0.07−1], p = .17) while a significant difference was observed for the second half (x̄diff = -0.03, 95% CI [-0.04, -0.01], p < .001), with faster RTs for the rich (x̄ = 925 ± 385 ms) than for the scarce location (x̄ = 955 ± 400 ms, see Fig. 2).

To complement this contrast analysis, we calculated Bayes Factors (BF10) for the difference between rich and scarce locations in both halves of the experiment. There was very strong evidence in favor of the null hypothesis for the first half (BF10 = 0.03), while strong evidence against the null was found in the second half (BF10 = 14.17), confirming that participants responded faster to targets in rich locations as the experiment progressed.

Experiment 2a – can differences in color variance cue target location?

Experiment 1 demonstrated that participants learned to associate target location probabilities with the color distribution of distractors during visual search. In the first experiment, only the mean of the color distribution varied, while all other parameters remained constant. Previous research has shown that humans can extract not only the mean from a distribution but also its variance and even its shape41,45,46. Subjectively, color distributions with high variance appear more heterogenous than those with low variance.

In Experiment 2a and 2b we investigated whether changes in the homogeneity of color distributions (reflected in their variance) would allow participants to distinguish between two distributions and assign different priority maps based on target location probability. Specifically, we tested whether different variances in the distractor color distributions could lead to statistical learning of location probabilities while the mean of the distractor color distribution remained constant.

Experiments 2a and 2b were identical except for the increased variance difference between the two distributions in Experiment 2b, to assess whether larger variance differences would lead to stronger learning of location probabilities from distributional variance.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-four volunteers (54% ♀, 22.13 ± 4.71 years old) from the University of Iceland took part. Since the number of trials was greater than in experiment 1, the experiment took about 1 h 30 min to complete, and participants were rewarded with 1,200 ISK.

Material and procedure

The two main differences between experiment 1 and experiment 2a were that distribution A and B were centered on the same color value but differed in variance (see Fig. 3). The low variance distribution had the same properties as those in Experiment 1 (a truncated normal distribution where 1 SD equals 3 JNDs, with a cut-off at 1.5 SD). In contrast, the high-variance distribution had the same shape and cut-off, but with 1 SD equal to 6 JNDs. As in Experiment 1, targets were positioned 4–5 JNDs away from the furthest distractor, and the color rotation for different participants was identical.

The second difference was that we assumed that differences in color variance might be more difficult to perceive than differences in average color, given that changes in variance can introduce a bias into the estimation of the average value of the ensemble72,73, which can make variance a trickier parameter to estimate. We therefore hypothesized that any potential effects might take longer to emerge, so we doubled the number of trials per distribution from 500 to 1000. Apart from these differences, the procedure was the same as in Experiment 1.

Analysis methods

The data were analyzed in the same way as in Experiment 1, except the controlled variable (C) now corresponded to whether the distribution had high or low variance.

Results

Average accuracy was 96.13% (± 2.6) and average RT was 1005.72 ms (± 232.23). To assess whether participants learned regularities associated with the variance of the distributions, we used the same approach as in Experiment 1, starting with a non-linear regression analysis (Eq. 1).

First, we fitted a base exponential decay model predicting RTs as a function of time-on-task. The upper asymptote was significantly different from zero (Y0 = 1216.57 ms, SE = 66.01; t(45309) = 18.43, p < .001), as was the lower asymptote (Yf = 838.35 ms, SE = 28.07; t(45309) = 29.86, p < .001), and the rate of decay (α = -6.36, SE = 0.04 ; t(45309) = -158.54, p < .001). Similar to Experiment 1, these results confirm that RTs decrease exponentially over time.

We then fitted a nested model that included the predictive property of the distribution (rich vs. scarce) as a fixed effect. Once again, all model parameters differed significantly from zero. However, no significant differences were found between rich and scarce locations: neither the upper asymptote (y0 diff = -6.76 ms, SE = 13.41 ; t(45306) = -0.5, p = .61), lower asymptote (yf diff = 0.43 ms, SE = 7.8 ; t(45306) = 0.05, p = .96) nor the rate of decay (αdiff = 0.01, SE = 0.05 ; t(45306) = 0.27, p = .78) showed significant differences. This indicates that RTs evolved similarly across the experiment, regardless of the target location (see Fig. 3), suggesting no interaction between location and RT.

Sample search displays from experiment 1 with (a) a distribution centered on color value 8 and (b) a distribution centered on color value 32. (c) Illustration of the shape and distance of both distributions. Each color on the x-axis is separated by 8 JND. (d) Predicted reaction times plotted as a function of time-on-task (as trial number) and the predictive property of the target’s location from experiment 1. The colored area around the regression line represents SEM (Standard Error of the Mean), and data points correspond to the binned RT average per 10 trials. (e) Predicted estimates of reaction times plotted as a function of time-on-task (first half vs. second half of the task) and the predictive property of the target’s location from experiment 1. Error bars correspond to the SEM (Standard Error of the Mean). Reaction times have been converted from log-values using an exponential function.

We also fitted a linear mixed model, predicting RTs based on time-on-task (first half vs. second half) and the predictive property of the target’s location (Eq. 2). The total explanatory power of the model was moderate (conditional R2 = 0.23), with the fixed effects accounting for 0.04. Time-on-task had a statistically significant negative effect on RTs (β = -0.13, 95% CI [-0.13, -0.12], t(45307) = -40.32, p < .001) while the predictive property of the distribution did not (β = 0.43− 2, 95% CI [-0.55− 2, 0.01], t(45307) = 0.86, p = .39). In contrast with experiment 1, the interaction between time-on-task and target location was not statistically significant (β = -0.16− 2, 95% CI [-0.02, 0.01], t(45307) = -0.22, p = .82).

Finally, we computed Bayes Factors (BF10) to assess differences between rich and scarce locations for both the first and second halves of the experiment. Strong evidence in favor of the null hypothesis was found for both halves (BF10 = 0.02 for each), so there was no evidence of participants responding faster to targets in rich versus scarce locations when only the variance differed between the distractor distributions.

Experiment 2b – increasing the difference in variance

Experiment 2a did not reveal any effect of distribution variance on the statistical learning of target location. While this may suggest that observers do not or cannot use variance as a cue for extracting statistical regularities, it is also possible that the difference in variance between the two distributions was too small for participants to perceive them as distinct ensembles.

In experiment 2b we therefore increased the difference between the distribution variances to further test whether variance could serve as a cue for predicting target location. If no effect is observed with this stronger manipulation, it would provide strong evidence that color variance alone cannot be a cue for statistical learning, at least not in the present paradigm.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-four volunteers (54.17% ♀, 23.58 ± 3.94 years old) from the University of Iceland participated. As in experiment 2a, the experiment took about 1 h 30 min to complete, and participants were rewarded with 1,200 ISK.

Material and procedure

The methods in experiment 2b were largely identical to those in experiment 2a, with the primary exception being the larger difference in variance between the distributions. The low variance distribution was a truncated normal distribution where 1 SD equals 1 JND, with a cut-off at 1.5, while the high variance distribution remained the same as in Experiment 2a (1 SD equals 6 JND; see Fig. 4). All other parameters, such as color rotation and trial structure, were consistent with Experiment 2a.

Analysis methods

The analysis methods were the same as in Experiment 2a.

Results

Average accuracy was 96.32% (± 2.18) and an average RT of 908.69 ms (± 87.48). As in the previous experiments, we began by conducting a non-linear regression analysis (Eq. 1). The base exponential decay model, predicting RTs based on time-on-task, revealed that both the upper (Y0 = 1163.95 ms, SE = 35.26; t(45906) = 33.01, p < .001), and lower asymptotes (Yf = 831.68 ms, SE = 13.77; t(45906) = 60.40, p < .001) were significantly different from zero, and this was also true for the decay rate (α = -5.74, SE = 0.03 ; t(45906) = -155.57, p < .001). These findings once again confirm that RTs followed an exponential decay pattern over time.

Next, we fitted a nested model by including the predictive property of the distribution as a fixed effect. While all parameters were significantly different from zero, no significant differences were found between the rich and scarce target locations. This applied to the upper asymptote (Y0 diff = -17.17 ms, SE = 17.24 ; t(45903) = -1, p = .32), lower asymptote (Yf diff = -7.71 ms, SE = 4.95 ; t(45903) = -1.56, p = .12) and the rate of decay (αdiff = -0.09, SE = 0.08 ; t(45903) = -1.19, p = .24). These results indicate that, as in Experiment 2a, RTs decreased similarly over time regardless of whether the target appeared in the rich or scarce location (see Fig. 4), suggesting no interaction between target location and RTs.

Sample search displays from experiment 2b with (a) a low variance distribution and (b) a high variance one, both centered on color value 8. (c) Illustration of the difference in variance of both distributions. Each color on the x-axis is separated by 4 JND. (d) Predicted reaction times from experiment 2b plotted as a function of time-on-task (as trial number) and the predictive property of the target’s location. The colored area around the regression line represents SEM (Standard Error of the Mean), and data points correspond to the binned RT average per 10 trials. (e) Predicted estimates of reaction times plotted as a function of time-on-task (first half vs. second half of the task) and the predictive property of the target’s location from experiment 2b. Error bars correspond to the SEM (Standard Error of the Mean). Reaction times have been converted from log-values using an exponential function.

We also performed a linear mixed model predicting RTs with time-on-task and the potential predictive power of variance. The total explanatory power of the model was moderate (conditional R2 = 0.17), with the fixed effects accounting for 0.08. Time-on-task had a significant and negative effect on RTs (β = -0.10, 95% CI [-0.11, -0.10], t(45904) = -37.62, p < .001) while different variances had no effect (β = 0.62− 2, 95% CI [-0.23− 2, 0.01], t(45904) = 1.42, p = .16). Unlike Experiment 1, the interaction between these factors was also not significant (β = -0.14− 2, 95% CI [-0.01, 0.01], t(45904) = -0.22, p = .83).

Consistent with Experiment 2a, Bayesian indicators very strongly supported the null hypothesis for both the first (BF₁₀ = 0.03) and second (BF₁₀ = 0.03) halves of the experiment, indicating that there is no evidence of participants responding faster to targets in rich versus scarce locations.

Discussion

Our current results demonstrate a novel pattern of how color distribution properties can influence the learning of statistical regularities of target locations. In experiment 1, we found a clear pattern of statistical learning cued by the color average of the distractor distribution: targets were found faster when presented in a rich location (where the target appeared on 80% of trials) compared to a scarce location (20% of trials), even though the rich location changed depending on the distractor distribution. In experiment 2a, we tested if similar learning would occur if the rich location was cued by the variance of the distractor distribution, but participants did not demonstrate any evidence of statistical learning, suggesting that contingencies between color variance and target location were either not detected or not used to guide visual search. Bayes factors further supported this interpretation as they revealed very strong evidence in favor of the null hypothesis. We found the same pattern of results even with an increased difference in variance between the two distributions in experiment 2b.

Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that different spatial priority maps can be associated with stimulus features and activated depending on the context33,34. Importantly, our study showcases that such associations can be made at the feature level rather than at the item level and are not restricted to any specific color, consistent with the importance of color in visual perception74,75,76,77. This also confirms that statistical learning is flexible, allowing adjustment of the weights of locations within the priority map depending on changing probabilities during the task25,78.

However, our study also highlighted a potential limitation to statistical learning, as color variance was not found to cue target location. Given how strongly our Bayes factors supported the null hypothesis in both experiments 2a and 2b, we can assume that this does not reflect a lack of statistical power. We know that changes in variance within stimulus ensembles can be extracted and are even available for explicit report46, so it is unlikely that participants simply did not notice the changes. We speculate that changes in variance were not interpreted as two distinct ensembles but instead as random variations of a single ensemble. This could be due to the fact that random variations are usually discarded when generating an inference79,80,81. Since rich locations were counterbalanced throughout the experiment, a uniform spatial priority map could have been established.

Could participants have noticed the contingencies between color variance and target location but opted to not use this in their search? We argue that this is unlikely, given that adjusting visual search to these contingencies would be the most optimal search strategy available. It is also unlikely that this null-result reflects a conscious decision in the choice of the search strategy as several studies suggest that statistical learning is largely implicit, where observers have little or no awareness of the spatial regularities of the target [e.g. 24,25,30. Although observers are often able to correctly report the most likely position of a target29,32,82 – meaning that some awareness of the statistical bias is available to them – this does not necessarily mean that the search itself is based on an explicit awareness of the target location probability. Given that statistical regularities in target location elicit a higher proportion of first saccades toward the most likely location, right after trial onset30, it is more likely that visual search is, in such scenarios, based on implicit attentional guidance rather than explicit search strategies.

The lack of any effect of color variance also echoes findings on color perception where color constancy is maintained despite variations in changing features such as illumination83,84. This suggests that color variation might not be useful for statistical location learning, therefore being unlikely to cue statistical regularities. Hence, small variations in color might be discarded as a cue when other information is available, such as spatial configuration55, real-world scenes rich in details57 or semantic information58. Thus, while statistical learning is a pervasive mechanism providing strong attentional guidance, it is limited by the type of available sensory information.

While we have focused here on highlighting differences in how color average and color variance affect statistical learning, other distribution parameters might be considered. Notably, the shape of feature distributions can be extracted43,44,45, but not explicitly in contrast to color average and variance46. One caveat regarding experiment 1 is that color average was confounded with color mode, making it unclear which one of these parameters was used as a cue for statistical learning. Introducing a color distribution where the two parameters are dissociated (such as a bimodal distribution) could provide valuable insights about which of these two parameters influence statistical learning and should be the focus of future research.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate how the average color within a color distribution can be a cue for target location probabilities. However, our results also show notable limits to this statistical learning as changes in color variance did not lead to any such cueing effects. We speculate that this reflects the generation of distinct spatial priority maps corresponding to different color averages, while color variance was discarded as random variations of a single-color ensemble.

Data availability

The original dataset of the three experiments and the analysis script are available at https://osf.io/6fczn/.

References

Kristjánsson, Á. Priming of probabilistic attentional templates. Psychon Bull. Rev. 30, 22–39 (2023).

Kristjánsson, Á. & Nakayama, K. A primitive memory system for the deployment of transient attention. Percept. Psychophys. 65, 711–724 (2003).

Frost, R., Armstrong, B. C. & Christiansen, M. H. Statistical learning research: A critical review and possible new directions. Psychol. Bull. 145, 1128–1153 (2019).

Turk-Browne, N. B. Statistical learning and its consequences. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 43, 117–146 (2012).

Aslin, R. N. & Newport, E. L. Statistical learning: From acquiring specific items to forming general rules. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 21, 170–176 (2012).

Turk-Browne, N. B., Scholl, B. J., Johnson, M. K. & Chun, M. M. Implicit perceptual anticipation triggered by statistical learning. J. Neurosci. 30, 11177–11187 (2010).

Caldara, R. & Seghier, M. L. The fusiform face area responds automatically to statistical regularities optimal for face categorization. Hum. Brain Mapp. 30, 1615–1625 (2009).

Ordin, M., Polyanskaya, L. & Soto, D. Neural bases of learning and recognition of statistical regularities. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1467, 60–76 (2020).

Turk-Browne, N. B., Scholl, B. J., Chun, M. M. & Johnson, M. K. Neural evidence of statistical learning: Efficient detection of visual regularities without awareness. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 21, 1934–1945 (2009).

Tobia, M. J., Iacovella, V., Davis, B. & Hasson, U. Neural systems mediating recognition of changes in statistical regularities. Neuroimage 63, 1730–1742 (2012).

Rungratsameetaweemana, N., Squire, L. R. & Serences, J. T. Preserved capacity for learning statistical regularities and directing selective attention after hippocampal lesions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 19705–19710 (2019).

Schapiro, A. & Turk-Browne, N. Statistical learning. in Brain Mapping vol. 3, pp. 501–506 (Elsevier, 2015).

Barlow, H. The exploitation of regularities in the environment by the brain. Behav. Brain Sci. 24, 602–607 (2001).

Conway, C. M. How does the brain learn environmental structure? Ten core principles for understanding the neurocognitive mechanisms of statistical learning. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 112, 279–299 (2020).

de Lange, F. P., Heilbron, M. & Kok, P. How do expectations shape perception? Trends Cogn. Sci. 22, 764–779 (2018).

Girshick, A. R., Landy, M. S. & Simoncelli, E. P. Cardinal rules: Visual orientation perception reflects knowledge of environmental statistics. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 926–932 (2011).

Li, B., Peterson, M. R. & Freeman, R. D. Oblique effect: A neural basis in the visual cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 90, 204–217 (2003).

François, C. & Schön, D. Neural sensitivity to statistical regularities as a fundamental biological process that underlies auditory learning: The role of musical practice. Hear. Res. 308, 122–128 (2014).

Bekinschtein, T. A. et al. Neural signature of the conscious processing of auditory regularities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 1672–1677 (2009).

Schubert, T. M., Cohen, T. & Fischer-Baum, S. Reading the written language environment: Learning orthographic structure from statistical regularities. J. Mem. Lang. 114, 104148 (2020).

Schooler, L. J. & Anderson, J. R. Does Memory reflect statistical regularity in the environment? (1991).

Bonte, M., Mitterer, H., Zellagui, N., Poelmans, H. & Blomert, L. Auditory cortical tuning to statistical regularities in phonology. Clin. Neurophysiol. 116, 2765–2774 (2005).

Romberg, A. R. & Saffran, J. R. Statistical learning and language acquisition. WIREs Cogn. Sci. 1, 906–914 (2010).

Jiang, Y., Swallow, K. M. & Rosenbaum, G. M. Guidance of spatial attention by incidental learning and endogenous cuing. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 39, 285–297 (2013).

Geng, J. J. & Behrmann, M. Probability cuing of target location facilitates visual search implicitly in normal participants and patients with Hemispatial Neglect. Psychol. Sci. 13, 520–525 (2002).

Jiang, Y. V., Swallow, K. M., Rosenbaum, G. M. & Herzig, C. Rapid acquisition but slow extinction of an attentional bias in space. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 39, 87–99 (2013).

Geng, J. J. & Behrmann, M. Spatial probability as an attentional cue in visual search. Percept. Psychophys. 67, 1252–1268 (2005).

Talcott, T. N. & Gaspelin, N. Prior target locations attract overt attention during search. Cognition 201, 104282 (2020).

Golan, A. & Lamy, D. Attentional guidance by target-location probability cueing is largely inflexible, long-lasting, and distinct from inter-trial priming. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0001220 (2023).

Jiang, Y. V., Won, B. Y. & Swallow, K. M. First saccadic eye movement reveals persistent attentional guidance by implicit learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 40, 1161–1173 (2014).

Jiang, Y. V., Sha, L. Z. & Sisk, C. A. Experience-guided attention: Uniform and implicit. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 80, 1647–1653 (2018).

Giménez-Fernández, T., Luque, D., Shanks, D. R. & Vadillo, M. A. Is probabilistic cuing of visual search an inflexible attentional habit? A meta-analytic review. Psychon Bull. Rev. 29, 521–529 (2022).

Hong, I., Jeong, S. K. & Kim, M. S. Context affects implicit learning of spatial bias depending on task relevance. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 82, 1728–1743 (2020).

Zhang, Z. & Carlisle, N. B. Explicit attentional goals unlock implicit spatial statistical learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 152, 2125–2137 (2023).

Fecteau, J. H. & Munoz, D. P. Salience, relevance, and firing: A priority map for target selection. Trends Cogn. Sci. 10, 382–390 (2006).

Bisley, J. W. & Goldberg, M. E. Attention intention, and priority in the parietal lobe. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 33, 1–21 (2010).

Wolfe, J. M. Guided search 6.0: An updated model of visual search. Psychon Bull. Rev. 28, 1060–1092 (2021).

Whitney, D. & Yamanashi Leib, A. Ensemble perception. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69, 105–129 (2018).

Alvarez, G. A. Representing multiple objects as an ensemble enhances visual cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 122–131 (2011).

Haberman, J. & Whitney, D. Ensemble perception: Summarizing the scene and broadening the limits of visual processing. in From Perception to Consciousness: Searching with Anne Treisman (2012).

Chetverikov, A. & Kristjánsson, Á. Representing Variability. Representing Variability vol. 0502 (Cambridge University Press, 2024).

Chetverikov, A., Campana, G. & Kristjánsson, Á. Building ensemble representations: How the shape of preceding distractor distributions affects visual search. Cognition 153, 196–210 (2016).

Chetverikov, A., Campana, G. & Kristjánsson, Á. Representing Color ensembles. Psychol. Sci. 28, 1510–1517 (2017).

Chetverikov, A., Hansmann-Roth, S., Tanrıkulu, Ö. D. & Kristjánsson, Á. Feature distribution learning (FDL): A new method for studying visual ensembles perception with priming of attention shifts. Neuromethods 151, 37–57 (2019).

Hansmann-Roth, S., Chetverikov, A. & Kristjánsson, Á. Representing color and orientation ensembles: Can observers learn multiple feature distributions? J. Vis. 19, 2 (2019).

Hansmann-Roth, S., Kristjánsson, Á., Whitney, D. & Chetverikov, A. Dissociating implicit and explicit ensemble representations reveals the limits of visual perception and the richness of behavior. Sci. Rep. 11, 3899 (2021).

Chun, M. M. & Jiang, Y. Contextual cueing: Implicit learning and memory of Visual Context guides spatial attention. Cogn. Psychol. 36, 28–71 (1998).

Chun, M. M. Contextual cueing of visual attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4, 170–178 (2000).

Jiang, Y. & Leung, A. W. Implicit learning of ignored visual context. Psychon Bull. Rev. 12, 100–106 (2005).

Zang, X. et al. Contextual cueing in co-active visual search: Joint action allows acquisition of task-irrelevant context. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 84, 1114–1129 (2022).

Geyer, T., Shi, Z. & Müller, H. J. Contextual cueing in multiconjunction visual search is dependent on color- and configuration-based intertrial contingencies. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 36, 515–532 (2010).

Jiang, Y. & Song, J. H. Hyperspecificity in visual implicit learning: Learning of spatial layout is contingent on Item Identity. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 31, 1439–1448 (2005).

Jiang, Y. & Chun, M. M. Selective attention modulates implicit learning. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. Sect. A. 54, 1105–1124 (2001).

Feldmann-Wüstefeld, T. & Schubö, A. Stimulus homogeneity enhances implicit learning: Evidence from contextual cueing. Vis. Res. 97, 108–116 (2014).

Kunar, M. A., John, R. & Sweetman, H. A. Configural dominant account of contextual cueing: Configural cues are stronger than Colour cues. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 67, 1366–1382 (2014).

Kunar, M. A., Flusberg, S. J. & Wolfe, J. M. Contextual cuing by global features. Percept. Psychophys. 68, 1204–1216 (2006).

Ehinger, K. A. & Brockmole, J. R. The role of color in visual search in real-world scenes: Evidence from contextual cuing. Percept. Psychophys. 70, 1366–1378 (2008).

Goujon, A., Brockmole, J. R. & Ehinger, K. A. How visual and semantic information influence learning in familiar contexts. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 38, 1315–1327 (2012).

Huang, L. Contextual cuing based on spatial arrangement of color. Percept. Psychophys. 68, 792–799 (2006).

Hardy, L. G. H. Tests for detection and analysis of Color blindness. Arch. Ophthalmol. 34, 295 (1945).

van Rossum, G. Python Tutorial. 143 (2018).

Raybaut, P. Spyder-documentation. (2019).

Witzel, C. & Gegenfurtner, K. R. Categorical sensitivity to color differences. J. Vis. 13, 1–1 (2013).

R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (2008).

Heathcote, A., Brown, S. & Mewhort, D. J. K. The power law repealed: The case for an exponential law of practice. Psychon Bull. Rev. 7, 185–207 (2000).

Viering, T. & Loog, M. The shape of learning curves: Areview. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 7799–7819 (2023).

Turatto, M., Bonetti, F., Pascucci, D. & Chelazzi, L. Desensitizing the attention system to distraction while idling: A new latent learning phenomenon in the visual attention domain. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 147, 1827–1850 (2018).

Pinheiro, J. & Bates, D. R Core Team. Nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R Packag Version. 3, 1–166 (2024).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting Linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, (2015).

Lüdecke, D., Ben-Shachar, M., Patil, I., Waggoner, P. & Makowski, D. Performance: An R Package for Assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. J. Open. Source Softw. 6, 3139 (2021).

Lo, S. & Andrews, S. To transform or not to transform: Using generalized linear mixed models to analyse reaction time data. Front. Psychol. 6, 1–16 (2015).

Jeong, J. & Chong, S. C. Adaptation to mean and variance: Interrelationships between mean and variance representations in orientation perception. Vis. Res. 167, 46–53 (2020).

Semizer, Y. & Boduroglu, A. Variability leads to overestimation of mean summaries. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 83, 1129–1140 (2021).

Alexander, R. G., Nahvi, R. J. & Zelinsky, G. J. Specifying the precision of guiding features for visual search. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 45, 1248–1264 (2019).

Hansen, T. & Gegenfurtner, K. R. Color contributes to object-contour perception in natural scenes. J. Vis. 17, 14 (2017).

Shevell, S. K. & Kingdom, F. A. A. Color in Complex scenes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 59, 143–166 (2008).

Gegenfurtner, K. R. & Rieger, J. Sensory and cognitive contributions of color to the recognition of natural scenes. Curr. Biol. 10, 805–808 (2000).

Wang, B. & Theeuwes, J. Implicit attentional biases in a changing environment. Acta Psychol. (Amst.). 206, 103064 (2020).

Friston, K. The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 127–138 (2010).

Knill, D. C. & Pouget, A. The bayesian brain: The role of uncertainty in neural coding and computation. Trends Neurosci. 27, 712–719 (2004).

Friston, K. et al. Active inference and learning. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 68, 862–879 (2016).

Vadillo, M. A., Linssen, D., Orgaz, C., Parsons, S. & Shanks, D. R. Unconscious or underpowered? Probabilistic cuing of visual attention. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 149, 160–181 (2020).

Foster, D. H. Color constancy. Vis. Res. 51, 674–700 (2011).

Giesel, M. & Gegenfurtner, K. R. Color appearance of real objects varying in material, hue, and shape. J. Vis. 10, 10–10 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Garpur Orri Bergs and Karolina Taudul for their diligent work in collecting the data.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant numbers PZ00P1_179988 and PZ00P1_179988/2, and TMSGI1_218247) and grants from the Icelandic Research Fund (#207045 and # 228366) and from the University of Iceland Research Fund. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P. B. and A. K. conceived the original idea. P. B., S. H. R. and A. K. designed the experiment. P. B. coded the experiment and conducted the statistical analyses, with support from S. H. R., D. P. and A. K. P. B. and D. P. wrote the manuscript with support from S. H. R. and A. K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Blondé, P., Hansmann-Roth, S., Pascucci, D. et al. Learning of the mean, but not variance, of color distributions cues target location probability. Sci Rep 15, 7591 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84750-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84750-0