Abstract

In recent years, the study of the deterioration phenomena and factors of oil paintings has attracted great attention from the scientific community. However, the number of articles that contain a study of the phenomenon of rust damage on paintings and an explanation of the mechanism of damage on canvas is small, so this article focused on studying the effect of rust resulting from the use of iron nails in fixing the canvas holder and due to aging and exposure to damaging conditions on colors containing metals (red–yellow–blue) in oil paintings, which results in damage products from rust, and different on the surface appearance of the colors and change the chemical composition of the color. This article aims to discuss (1) the phenomenon of rust that affects paintings (2) the problems associated with the effect of rust that migrates through the layers on the rest of the parts of the painting other than the colors, such as the canvas layer and the preparation layer (3) describing the mechanism of atmospheric corrosion of iron by interacting with ground colors (red ochre–yellow ochre–blue) using experimental models covered with rust and exposed to thermal and light aging to evaluate damage before and after accelerated aging and the most important damage products (4) and the evaluation of damage was done by using color change measurement For the samples, the front and back morphological surfaces of the fabrics were monitored before and after aging through the average color measurements of the three colors. It became clear that the blue color shows the greatest change after complete aging in color ∆E = *42.7 Followed by red, which shows a complete change in color ∆E* = 23.6, followed by yellow, which shows a complete change in color, ∆E* = 21.7. Microscopic examination showed that the rust was distributed in an uneven manner on the back surface of the fabric, and the front surface with the colors, and the appearance of large orange spots on the surface randomly, and the appearance of fine cracks penetrating the layers in the areas mixed with iron rust products, and their mixing with the color grains. The change in the chemical composition of the colors was monitored before and after aging by FTIR, EDS, which showed changes in terms of the appearance of the iron element (Fe) and an increase in its concentration after aging, which confirms that the color was affected by iron rust resulting from the rust of the iron nails fixed to the fabric layer stained with rust that migrates through the layers that are damaged due to the migration of Fe2+ ions to the surface of the colors in the presence of alkaline metal cations in the chemical composition of the three earth colors. In the presence of moisture, the damage increases because the ionic diffusion across the thickness of the formed film leads to the disintegration of the paint because the polarization of the cathodic substrate encourages the migration of cations through the color layer, and the color change in the yellow and red colors resulted from the presence of the iron ion that reacts with Fatty acids in oil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Paintings undergo chemical, mechanical and biological damage over time. While chemical and biological changes have been extensively studied in recent decades, the study of the mechanical behavior of oil paintings deserves more attention. Damage to paintings (such as cracks, rust or peeling) has traditionally been associated with fluctuations in humidity and temperature. While such assumptions are not entirely wrong, the environment is not always the cause of the observed failure of paintings, but rather internal damage such as the deterioration of the medium over time that affects the different layers of paint. The causes of damage to paintings must be studied to ensure that paintings are treated and preserved over time1.

Iron rust from nails that were used in fixing canvas may play a major role in the damage of old oil paintings when exposed to uncontrolled environments, numerous internal and environmental factors can cause oil paintings to deteriorate. Variations in the physical characteristics of the layers cause internal problems where the environment changes, cause strain and harm to the painting’s basic structure2,3,4.

The study of the mechanical behavior of oil paintings deserves more attention. Damage to paintings (such as cracks, rust, or peeling) has traditionally been associated with fluctuations in humidity and temperature. While such assumptions are not entirely wrong, the environment is not always the cause of the observed failure of paintings. The interactions between pigment and medium, as well as between different paint layers, are crucial to interpreting damage to the painted surface, but also to making good conservation decisions to ensure the stability of paintings5,6.

There are several ways that deterioration might appear including cracks, craquelure (microcracks), fading, darkening, blanching7, multiple paint layer flaking areas, separation from the foundation, preparation layers, surface protrusions, separation of color, disturbance, and formation of rust products from the contact of iron nails with the oil painting canvas8,9.

In addition, the linen layer support is compromised. Degradation results from cellulose’s hydrolysis and oxidation, which are influenced by temperature, pH, moisture content, and crystallinity level. The process of crystallization and chain bond breakdown take place. Linear cellulose; β-(1,4)-glycosidic, causes cellulose to depolymerize, which results in the mechanical qualities of oil paintings on canvas being lost10,11,12. Unsuitable environmental conditions have an impact on the iron nails used to secure the canvas easel. It causes rust to develop in the nails that come into touch with the canvas and rust compounds to spread throughout the layers and the fibers are affected and become more brittle and susceptible to breakage in the rust area13.

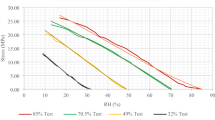

Three types of atmospheric corrosion can be distinguished based on the amount of moisture present on the damaged metal’s surface: A certain relative humidity value is required for dry atmospheric corrosion, tidal atmospheric corrosion, and wet atmospheric corrosion. This figure is known as critical relative humidity, and it is exceeded when the environment’s relative humidity rises above it, causing the metal to corrode more quickly. Different metals have varying relative humidity levels; iron and other regularly used metals have a relative humidity of 65%14.

It is an intriguing topic when it comes to corrosion because of the component of atmospheric aerosols. In addition to the oxygen and moisture found in the ground, the chem-aerosol components have the ability to dissolve the protective layers that prevent corrosion on the metallic surface. Sulfates, nitrates, carbonates, and ammoniums make up the chem-aerosols15.

The best relative humidity range for oil painting is between 40 and 60%, and the ideal temperature range is between 18 and 24 °C (65- and 75-degrees Fahrenheit). These circumstances offer a steady atmosphere that facilitates oil paints’ appropriate aging and drying. Higher humidity and temperatures outside of this range might hasten unwanted chemical processes including oxidation and hydrolysis, which may compromise the lifespan and integrity of paint films16.

Rust can develop on the nails used in an oil painting when it is exposed to high humidity, which occurs when iron corrodes in a moist environment with dissolved oxygen. This is particularly true in places close to the colors. The painting’s surface can then gradually turn into a layer of rust-colored corrosion products. Higher oxidation state layers arise in the exterior layer of corrosion products, which are often stacked with lower oxidation state chemicals and form immediately on the metal surface17. In exterior layer corrosion products, magnetite (Fe3O4) is the most frequent iron oxide detected on archaeological iron, and it is often found next to the metal surface.

One of the studies conducted to study the effect of rust on fabric is a study of a Qing Dynasty Chinese armor consisting of an outer and an inner layer18, The outer layer is cotton fabric, and the inner layer is iron sheets, the two layers of which are fixed together with nails. The cotton fabric is stained with rust compounds due to the severe corrosion of the iron sheets.

Rust affects the fibers and they become more susceptible to breakage in areas stained with rust compounds. This is due not only to the corrosion of iron rust but also to the acidic decomposition of the fibers accelerated by metal ions19,20.

The most common iron compounds that can be recognized in these products are goethite (α-FeOOH) and lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH), Additionally, iron, oxygen, and chlorine were found in the orange and brown patches, indicating the existence of akageneite and Goethite21.

When iron nails are exposed to the atmosphere, the following process occurs in Eqs. 1, 2:

In exchange, in saline aerosol media, the primary reaction is:

Because the oxidation process can be accelerated by the presence of the chloride anion, resulting in the creation of the Fe2+ slightly hydrated basic oxide. Following this, the processes occur in accordance with the components’ creation sequence from the rust layer structure: the Fe3O4 (inert) loadstone, the α-FeO(OH) lepidocrocite, the α-Fe2O3 hematite, and the α-FeO(OH) goethite. Goethite transforms into lepidocrocite by crystalline reforming processes, whereas lepidocrocite transforms into loadstone through a gradual aging process hase in surface layers, while goethite and magnetite are often found in the inner layer of rust scales and exhibit isolating behavior22. In this step, Fe2+ ions spread in water-saturated pores and cracks based on their domain stability, and in regions with restricted oxygen availability, they precipitated as magnetite in the form of inter-dispersed phases in iron (III) oxyhydroxides at the interior layer (dark phase). Fe2+ ions were transformed at the internal and exterior layer into iron (III) oxyhydroxides such goethite and lepidocrocite at locations with greater oxygen accessibility23.

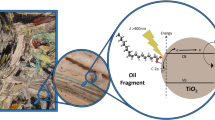

Ferric oxyhydroxide generation is linked to volume expansion, which exfoliates the corrosion layers and creates fissures, perhaps hastening the degradation. There is an orange powder that has been identified as akagane´ite, or b-FeOOH. Additionally, to prevent akaganeite production and related corrosion, the iron should be kept and shown at less than 20% relative humidity24. Siderite (FeCO3) is also present in carbonate settings25. Akageneite β-FeO(OH) and occasionally β-Fe2(OH)3Cl can develop when chloride ions are present26. Moisture diffusion has the potential to exacerbate corrosion by weakening the physical and chemical bonds that are formed between the paint layer and the metal, which can lead to binding medium swelling and hydrolysis. The paint layer may delaminate as a result of the metal modification products’ increased volume, especially those containing iron. One notices an orange tone caused by iron corrosion products. The presence of salts in the interface, which can promote osmotic pressure gradients; and the generation of hydroxyl ions by the cathodic reaction which creates an increase in alkalinity, are also mentioned as factors that can contribute to blister formation and delamination of the paint layer. So, the interaction between iron rust and archaeological oil paintings can significantly impact the colors and overall preservation of these valuable artworks27.

The colors change is occurred due to the low relative humidity, as the medium absorbs water and the adhesive force between the color atoms is lost. Therefore, a large amount of fine grains became visible on the surface, as well as the formation of small pits on the surface of paint, and the surface becomes uneven due to the basic formation28.

Rust and corrosion products, resulting from the nails fixed to the rust-stained cloth layer, migrate through the layers that are damaged due to the migration of Fe2 + ions to the surface of the colors in the presence of alkali metal cations in the chemical composition of the colors such as hematite red, gossite yellow and ultramarine blue. In the presence of moisture, the damage increases because the ionic diffusion through the thickness of the formed film leads to the disintegration of the coating because the polarization of the cathodic substrate encourages the migration of cations through the color layer29.

Several analytical techniques help to identify the components of the studied painting and highlight its deterioration mechanisms to develop a suitable conservation plan, Different analytical methods used for investigation of the formation of degradation products and crosslinked materials30. These techniques include a USB Digital microscope, Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) used to study the surface and the various deterioration aspects, such as cracks and iron rust morphology, also, used color measurements, Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy Analysis and Fourier transform infra-red spectroscopy (FTIR) to identify and observe of microstructural characteristics and elemental analysis of the iron rust and oil paint layers, such as binders and pigments and changes in function group31.

This study aims to identify the causes of damage to oil paintings when they come into contact with iron, such as iron nails used to fix the canvas of the painting, which also affect the colors, and the mechanism of damage and to estimate the various changes that may occur as a result of this interaction or contact between them.

Materials and methods

Materials

Preparing samples

This study was carried out on the three colored ground oxides (ocher red–gothite yellow–azurite blue), the colors is consisting of ground oxides that are based on silica, such as quartz, clay, carbonates, and sulphates. The yellow and red color is accompanied by kaolina, because silicate pigments contain a large number from natural elements32. The samples were made based on a study conducted on several paintings in the Manial Museum at Egypt, as painting Turkish baby with registration number 49/2 and size 70 cm × 52 cm & painting Landscape painting, size 44 cm/70 cm, oil on canvas, signed “F. Zomaro” and registration number 79 which showed the effect of rust on the front surface of the paintings, especially the colors, as Fig. 1.

A study of the phenomenon of rust on some paintings in the Manial Museum in Cairo, Egypt, such as the painting of the [(a). front of Turkish Child painting shows traces of iron nails rust, (b). Back of the Turkish Child canvas shows traces of iron nails rust on the back of the painting], [(c). front of The City painting shows traces of iron nails rust, d. Back of The City painting shows traces of iron nails rust].

Color samples were prepared by using the same preparation methods used in the old method in oil painting33. Three colors red, blue, and yellow were prepared by using color oxides, the samples dimension is 4 cm × 4 cm in length and wide. The rusty iron nails were placed and fixed on the surface of the colors and exposed to continuous humidity for 10 days34, then they were left dry and then and then aged for 100 h by hygrothermal aging, Thermal aging oven (temperature + relative humidity) type (SHEL LAB) at the National Research Center, Polymers Department under an temperature of 120 ± 2 °C and a humidity of RH 80 ± 5% for 48 h to obtain the same aging conditions that exposed to oil paintings and iron nails35, as Figs. 2, 3, 4.

Methods

Morphological examination

USB digital microscope

A USB digital from GAOSUO Digital Engineering Dept., Image CMOS Sensor, Controller High-Speed DSP (Driver Free available), Focus Range 0–40 mm, Built-in 8 White-light LED, Still Image Capture Resolution 640 × 480-1600 × 1200, Frame Rate 30 f./s under 600 LUX Brightness, Digital Zoom 5X Sequence Mode, Magnification Range: 1000X. was used to analyze the collections. A digital microscope is a favorite in the examination for convenient carrying and usage in the workplace; it has been used to record the deteriorating features and investigation of color’s surface at various magnifications.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

Colors surfaces and iron rust effect on it were examined with Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Oxford detector, JEOL JSM 5400 LV EDX Link ISIS model, it is designed for high-resolution imaging and microanalysis of a wide range of materials. The instrument features a tungsten filament as the electron source and provides a magnification range from 8× to 300,000x. The samples were inspected after gold coating at a high vacuum, The sample size used is 1 cm.

Color measurements

Color surface inspection was performed to evaluate the color change of the samples both before and after aging by using a Color i7 benchtop spectrophotometer (Color i7, X-rite, USA), reflectance / transmittance reference-level, Measurement time 2.7–4.0 s (flash & data acquisition), Duty cycle 480 measurements per hour max, Spectral Range 360–750 nm, Wavelength Interval 10 nm, Photometric range 0.0–200%, Photometric resolution 0.001% reflectance, as well as the difference values (ΔE) for all color samples before and after deterioration.

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis (EDS)

The three-color samples (Blue, Yellow and Red) were analyzed with scanning electron microscope coupled with (SEM–EDS) model Prisma E (thermos fisher company), Frequency: 50 or 60 Hz, Voltage 100–240 V AC. samples were fixed on aluminum stubs with standard diameter using a carbon double sticky tape, The sample size used is 1 cm.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The three-color samples (Blue, Yellow and Red) were analyzed with FTIR spectroscopy. The FTIR spectra were recorded using a The Agilent Cary 630 FTIR. The spectra were obtained in the range from 7000 to 350 cm–1 using FTIR absorption analysis, with a scan resolution of ≤ 2 cm–1, Measurement time < 10 s. Samples were made by mixed powder sample was with 200 mg of dry KBr then milled in an agate mortar and pressed to be pellets.

Results and discussion

Morphological examination

USB digital microscope

The surface colors of the samples were examined before and after aging. Microscopic examination of the surface colors showed the appearance of iron rust on the surface mixing with color grains, which led to clear changes in the three-color shades, as they turned dark and the appearance of rust products characteristic of iron rust in orange, brown, or orange-yellow color. All of the colors contributed to the separation of the color grains in the regions impacted by the rust products by slipping between the color grains and emerging from behind them. Iron rust products were also evident in the areas where the iron nails that were permeable to the canvas were located, and the surrounding region was also covered in iron rust products. The blue color before damage is bright as shown in Fig. 5a but after damaged was the color most affected by damage, as cracks appeared, separation of the color layer, and blackening in other areas, especially the areas affected by iron rust also the color appeared darker as shown in Fig. 5b, and its surface was covered with dark brown rust products and black color in other areas as we show in Fig. 5c and d. As for The yellow color before damage is bright as shown in Fig. 5e but after damaged the microscopic examination showed the appearance of products iron rust in a dark yellow or yellow–brown color as we show in Fig. 5f and g, and the color was more consistent than the blue color, The examination also showed that the position of the nail greatly affected the condition of the fabric, and iron rust appeared mixed with the layers of fabric and color as shown in Fig. 5h. As for the red color before damage is bright as shown in Fig. 5I, but after damaged a white color appeared on the surface of its samples in some places as shown in Fig. 5j, with bright spots appearing on the surface resulting from the products of iron rust in a light yellow color with color changes as shown in Fig. 5k and the red color turned into the light color in other places and the mixing of rust products with the surface of the color and their penetration with the appearance of fine cracks penetrating the color layer and the photography ground in areas mixed with products of iron rust, and the surface appearance of the red color was more cohesive and homogeneous in its grains like the yellow color as shown in Fig. 5l.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

Color samples were examined before and after aging using a scanning electron microscope as Fig. 6a, b, c, d, e, f. The results showed that all color samples before aging had a very smooth, soft, and homogeneous surface, and the surface showed the presence of the oily medium mixed with the color granules. As for the samples after aging, the examination showed surface roughness and disintegration of color granules with the appearance of formation. The distinctive crystalline of the products of iron rust and their penetration and intermingling between the color grains mixed with calcite crystals with the disappearance of the oily medium that used to give the color surface a homogeneous, shiny appearance. The (SEM) examination of the blue color as Fig. 6a showed the homogeneity of the surface before aging but the samples after aging, Fig. 6b the appearance of the crystalline formation of iron rust with the disintegration of the color grains and the penetration of rust products between the grains. Showed calcifications of rust products on the surface of the color with the appearance of space and gaps in the color surface and loss in some area and the brightness in the areas affected by iron rust. The examination (SEM) of the yellow color as Fig. 6c the homogeneity of the surface before aging but the samples after aging, Fig. 6d showed the disintegration of the color granules and the mixing of rust products with them and their penetration inside. As for the examination (SEM) of the red color as Fig. 6e the homogeneity of the surface before aging but the samples after aging, Fig. 6f, it showed the presence of some cracks in the color layer with the spread of crystalline calcification of the iron rust and their penetration into the cracks and mixing with the color granules.

Chemical interactions between the two layers can lead to significant visual changes. The most obvious is due to the migration and diffusion of metallic ions into the paint layers. Iron corrosion often leads to an orange-brown color change in the paint layer. Also shows white granular paint layers which are tinted due to corrosion of the iron support (orange, brown). The orange color visible in both layers is clearly due to the presence of (Fe). The metallic ions (mostly Fe3+) most likely migrated into the paint layers from the metal following the oxidation of the underlying metal36.

Color measurements

The degree of change in colors were measured according to the following Eq. (3):

The values of color alteration of the selected color samples varied as in the Table 1, And the images placed in the table are illustrative images of the color changes that occurred in the experimental samples before and after aging, taken with a camera. The result indicated that the color with the highest ∆E values were recorded in the blue color and the lowest ∆E values in the case of yellow, as for the red color, its color change value was average between the color change values of the previous two colors but closer to the change value for the yellow color,, which confirms that the blue color was the color most affected by damage and rusting of iron, while the yellow color was the least affected by damage and rusting of iron.

In truth, oil paintings may become more yellow when placed in the dark and lose it when exposed to light after being stored in a dark environment, heated, or humidified. Recent color measurements have shown ΔEs of 4–15 units, which indicate a significant and continuous loss of yellowness over years with little sign of when it would reach an end-point37.

In the case of pigments, Discoloration is the primary modification in visual and color measures (i.e. fading, darkening, color change). Exposure to light, heat, relative humidity, reactions with air pollutants including sulfur and nitrogen-containing gases, restoration efforts, iron rust, and metal corrosion are some of the causes of these alterations38,39.

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis (EDS)

It is an analytical technique used for the elemental analysis as in Table 2, Fig. 7a–f of the color samples before and after aging showed that the colors appeared to change in terms of the appearance of new elements that were not present in the samples before aging, as all samples showed the appearance of the element iron (Fe) in the blue color after aging, also the iron concentration increases in yellow and red colors after aging. The analysis confirmed that the blue color as Fig. 7a, b after aging appeared in a high concentration of iron at a rate of 14.1%, while the blue color before aging was completely devoid of iron. The concentration of the oxygen element in the blue color after aging also increased by a percentage of (32.6% to 37.7%) As for the analysis of the yellow color as Fig. 7c, d, it confirmed that the basic composition of the color consists of one of the iron compounds, but the analysis showed an increase in the concentration of the iron element in the yellow color sample after aging from 18.4 to 22.5%, as well as an increase in the oxygen element in the yellow color after aging. With a percentage of (31.7–38.7%), which confirms that the color is affected by the rust of iron resulting from the rust of iron nails. As for the red color as Fig. 7e, f, the analysis showed a significant increase in the concentration of the iron element, and because the chemical composition of the red color consists mainly of iron, we find that the concentration of the iron element has increased. The change increased from (18.5–29.7%), and the oxygen element in the red color increased after aging by (32.7–39.5%), which confirms that the colour was affected by iron rust in its internal composition. The appearance of iron in blue color after aging and its concentration increasing in yellow and red colors after aging, as well as the increase in the concentration of the element oxygen (O) by a large percentage in all samples after aging, confirms that iron rust has greatly interfered in the internal composition of colors, which led noticeably to the appearance of changes. Color in all three colors, with the appearance of rust spots on the surface, which distorted the general appearance of the colors, which also confirms the formation of iron rust products on the surface of the color and inside its grains. The carbon element’s concentration dropped in the blue color (from 21.4 to 16.9%) and the yellow color (from 35.6 to 22.6%) after aging, according to the analysis, which also verified a decline in the carbon element’s concentration in all color samples. As for the red color, the concentration decreased Carbon element (from 16.8 to 15.8%), which confirms the decomposition of the organic medium binding the color granules, their disintegration and separation, and their effect on heat and humidity.

Iron nails frequently cause oil paintings to gradually deteriorate. The mechanisms and kinetics involved in this phenomenon are dependent on a number of variables, including the storage environment (controlled or uncontrolled, with temperature and relative humidity fluctuations), pollution particles, the presence of other hazardous materials, and prior use or restoration procedures. Because of this, metal corrosion products may develop and stain the paint layer, detracting from the object’s visual appeal. More significantly, as they continue to develop, the colors may become badly faded due to fissures, color changes, blistering, and flaking. The carbon in the sample or the carbon adhesive tabs used to adhere the sample might be the source of the carbon40. Additionally, the development of iron rust products is confirmed by the rise in carbon and oxygen during age. In addition, the organic mediator’s carbon causes a reaction with iron that results in the creation of siderite, one of the byproducts of iron rust. Wet-dry cycles are the primary driver of long-term atmospheric corrosion processes. The amount of iron oxidized exceeds the associated oxygen intake, just as it did during the wetting stage41.

Metal oxide is a chemically unstable condition that occurs when metal and oxygen come into contact. For evident geometrical considerations, a metal can only react with oxygen in the vicinity of its surface. Consequently, a coating of metal oxide covers every non-metal surface42. Iron oxidation proceeds quickly as a result of the easier access to oxygen, and Fe++ ions are formed. Along with the production of hydrogen ions, iron oxide hydroxide (FeOOH) is deposited43.

This is caused by both the hydrolysis of fiber acid, which is sped up by metal ions, and the corrosion of iron rust44. Iron rust through the layers of oil paintings, causing harm to the colors and overall deterioration. There will be a noticeable drastic shift in the color medium. There is a reduction of adhesive strength between the color atoms and a partial loss of the color medium45, It made it easier for the sample’s surface to develop tiny holes caused by the leading dissolving processes. Additionally, when the saturated fatty acids spread out of the paint and crystallize on its surface, they cause cracks to develop and accelerate degradation46 and have a destructive effect, not just on the painting’s look but also on the structural composition’s integrity because of the development of metallic soap, which causes the color medium and colors to (partially) deteriorate47. Red and yellow represent the separation of the mineral soap from the medium, the fatty acid crystallization, and its surface dispersion. The degradation process operates by the formation of metal soaps that permeate into paint and decrease adhesion, which is caused by metal ion interactions with the lower acids created by paint oxidation, or by chemical reactions between metal cations and the pendant carboxylic groups of oil paint48.

At the oil paint/iron interface, poor surface wetting and flawed chemical bonding result in gaps that limit interfacial contact and retain moisture and air. Differences in dried paint thickness between the interior and exterior of voids might lead to further issues by creating strains that lower paint stability49. The presence of water at the metal–polymer border might cause loss of adhesion when these issues are coupled with linseed oil paint’s susceptibility to water and ionic ions50.

we notice the blue color changing to gray in some parts due to the deterioration of the oil in the presence of moisture on the surface of the color51, and reaction calcium in the color composition with the oil due to the increase in moisture on the surface of the color52. Ultramarine blue can have a catalytic effect on the deterioration of the color medium which may explain the non-uniform appearance of the deterioration of the blue color53, The red color change occurs in some red areas as a result of unsuitable environmental conditions. Iron is redistributed during weathering, and iron is released during the decomposition of primary aluminosilicates, increasing the iron content (Fe), indicating that Fe forms a distinctive mineral of the (iron oxides) phase54.

The color change in yellow and red is due to the presence of iron ions that react with the fatty acids in the oil55, The darkening of the color is explained by the partial conversion of red Fe2O3 to black Fe3O456, The yellow color is damaged as a result of the decrease in the components associated with the alkaline content in its chemical composition57.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

An essential test for determining the extent of trace degradation at the molecular level is FTIR spectroscopy58,59. where the structural information of infrared spectra is determined60,61.

It was proven that the yellow color is goethite FeOOH due to the appearance in the spectrum of an absorption peak at wavelengths 898.7 cm−1 and 2925.7 cm−1.

hydroxyl group OH at wavelength 3650 cm−1 3430 cm−1 and the group Al –OH spectrum showed an absorption peak at wavelength 938 cm162,63. The spectrum showed an absorption peak at wavelength 1085.5 cm−1, which is attributed to the Si–O–Si and Si–O–Fe groups, which play an important role in determining the components of ochre. Which is the include of other minerals, as clay minerals. The spectrum at wavelength 593.2 cm−1, which is attributed to the group (Fe–O stretches)64, and sulphate at 593.2 cm−1, 648.8 cm−165. The same compounds appeared after damage, with a difference in the wavelength and intensity, and appear new compound as magnetite appearing at wavelength 602.3 cm−1, The peaks of pyrite (Fe = S), stretching of S–S at wavelength 1150–1160 cm−1 and 602 cm−1 66, We noticed an increase in the intensity of the esterification curve and wavelength may be observed from (1734.9–1744.5 cm-1) after damage due to aliphatic ester formation or saponification as shown in Fig. 8a.

As for the red samples before damage we noticed the spectrum of wavelengths at 864.366 cm−1 and 471.7 cm−167,68 which is attributed to FeO. In the red ocher pigment, it is accompanied by the presence of quartz through the (Si–O–Si) group at wavelength 1032.1 cm−1, and the same compounds appeared after damage, with a difference in wave number and intensity, and appear new compound as with magnetite appearing at 602.3 cm−1, the presence of ferrous sulfate is at 604.8 cm−1, The presence of siderite is at 1068.7 cm−1. We noticed an increase in the intensity of the esterification curve and decrease wavelength from (1742.8–1701.1 cm−1) after damage due to aliphatic ester formation or saponification as a result of saponification as shown in Fig. 8b.

As for the samples of synthetic ultramarine blue color appeared at wavelength 2927.1 cm−1. before damage, as well as aluminum silicate groups [(Al6Si6) O24] at wavelengths 774.6 cm−1 and 607.7 cm−1, and a sodalite group at wavelengths 1077.0 cm−1 and 1167.9 cm−1 which is attributed to the Si–O stretching band group69. An absorption peak was visible in the spectra at 1420 cm−1 in wavelength70, which is attributed to the CaCO3 group. The same compounds appeared after damage, with a difference in the wave number and intensity. You may notice a decrease in the intensity of the esterification curve and wavelength from (1734.1 cm−1 before to 1730.5 cm−1 after) as a result of saponification as well as the appearance of the iron rust production as magnetite of strong signals at 588 and 3437 cm−1, Goethite spectrum strong peaks at 615, 798 and 905 cm−1 respectively, together with two broad bands at 3136 and 3431 cm−1, The Lepidocrocite spectrum stood out by the presence of a main peak at 1023 cm−1, followed by several secondary signals at 485, 615, 759, 1152, 3014 cm−1 and 3414 cm−1, as shown in Fig. 8c. The akaganeite standard yielded a wide band at 3385 cm−1, two faint signals at 844 and 1623 cm−1, and a strong double peak at 648 and 693 cm−1. the principal constituents are lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH), magnetite (Fe3O4), and akaganeite (β-FeOOH), with a little quantity of maghemite (γ-Fe2O3)71,72.

We find that the hydroxyl group OH increased from 3437.1 cm−1 before damage to 3446.3 cm−1 after damage, and the C-H Stretching group decreased slightly, from 2927.5 cm−1 before damage to 2927 cm−1 after damage, indicating that the water content of cellulose was affected by the fabric of the support causing breakage Converting long molecular chains into short chains, and the C=O group increased from 1401 to 1452 cm−1, which indicates the influence of the group hemicellulose73.

Conclusions

The study’s findings demonstrated that the iron nails used to secure the canvas in old oil paintings under improper circumstances rusted and impacted the fabric that came into contact with the rust over time. This can cause the layers of the paintings, including the canvas holder, to deteriorate, as demonstrated by the experimental samples’ appearance after aging. a shift in the canvas’s color and the development of rust spots as a result of iron oxides interacting with the canvas when oxygen and moisture are present. The canvas is affected and become more brittle and susceptible to breakage in the rust area and the appearance of holes, weakness of the canvas and corrosion. This was indicated by USB microscopic examination, SEM and FTIR analysis showed a loss of content. The hydrolysis of cellulose and the effect of hemicellulose through the change of function groups before and after deterioration, which led to weak fibers and fragility.

The color layer is affected by iron rust, and this appeared with the experimental samples after aging of the colors (hematite red, goethite yellow, ultramarine blue), which showed many aspects of change and deterioration. Which was revealed through examination with (SEM–USB) or analysis with Color Measurements, FTIR, EDS.

The blue color is the color most affected by damage, as cracks, separation of the color layer, and blackening appeared in other areas, especially the areas affected by iron rust. The color also appeared darker, and the crystalline formation of iron rust appeared, where a mixture of iron (II) oxide, FeO, and iron (III) oxide, Fe2O3, was formed in addition to iron (III) hydroxide FeO(OH) Fe(OH)3 with the disintegration of the color granules and the penetration of rust products between the granules, the medium and the colors lose the strength of cohesion between the atoms, causing the particles to appear clearly on the surface and the surface suffers from concavity. The change in the mechanical properties of the paint and the formation of cracks and color change occurs. The result of the reaction of calcium present in the color composition with oil due to increased humidity and acidic contaminants that attack the color.

As for the yellow color, it appears that the iron rust products appear in a dark yellow or yellowish-brown color, and the color granules disintegrate and the rust products that contain the iron ion mix with them and penetrate inside Which reacts with the fatty acids in the oil and produces mineral soap as a result of moisture, the formation of soap, and an increase in the transparency of the paint layer. The formation of a crust and the accumulation of mineral soap on the surface leads to increased fragility and loss of strength of the bond between the color atoms and the medium.

As for the red color, a white color appeared on the surface of his samples in some places, with shiny spots appearing on the surface resulting from the products of iron rust, in a light-yellow color with the color changing, and cracks occurring in the color layer as the crystalline calcification of the iron rust spread and penetrated into the cracks and mixed with the colored grains. This is explained. The darkening of the color is the result of the conversion of red Fe2O3 molecules to black Fe3O4 due to the rich atmosphere (SO2).

Color measurements confirmed that blue was the color most affected by iron rust, while yellow was the least affected by iron rust. EDS analysis of color samples before and after aging showed that the colors appeared to change in terms of the appearance of new elements that were not present in the samples before aging. All samples also showed the appearance of iron (Fe) in blue color after aging, and the concentration of iron in yellow and red colors increased after aging. An increase in the concentration of Fe leads to the destabilization of kaolinites due to mineral transformations, which consist either of increasing iron concentrations through gradual replacement or replacing kaolinite with hematite, Also, The FTIR provide the same EDS results confirmed changes in all colors.

These findings all support the presence of iron rust on all sample colors and its detrimental impact on the colors and their grains, which altersthe appearance or the internal composition of the color.

Based on the above results, we recommend that to treat this phenomenon, all nails used to fix the canvas are removed, then the nails are treatment by immersing them in corrosion inhibitors, then fixing them again, or but a strip of treated textile against iron rust on top of the canvas in the place where the iron nails were placed.

Data availability

Every dataset was acquired, utilized, and examined for the current investigation. They were incorporated into this document.

Change history

23 May 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Acknowledgements section in the original version of this Article has been removed.

References

Mecklenburg, M. F. Methods and materials and the durability of canvas paintings: A preface to the topical collection Failure Mechanisms in Picasso’s Paintings. SN Appl. Sci. 2(12), 2182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-03832-6 (2020).

He, X., Xu, M., Zhang, H., Zhang, B. & Su, B. An exploratory study of the deterioration mechanism of ancient wall paintings based on thermal and moisture expansion property analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 42(194), 200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2013.10.035 (2014).

Kehlet, C., Kuvvetli, F., Catalano, A. & Dittmer, J. Solid-state NMR for the study of Asger Jorn’s paintings. Microchem. J. 125, 308–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2015.11.010 (2015).

Calicchia, P. & Cannelli, G. B. Detecting and mapping detachments in mural paintings by non-invasive acoustic technique: Measurements in antique sites in Rome and Florence. J. Cult. Heritage. 62, 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2004.11.001 (2005).

Mohie, M. A., Ali, N. M. & Bani Issa, A. A. A new method of lining oil paintings using polyurethane. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeometr. 19, 9–21. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3066004 (2019).

Osticioli, L. et al. Analysis of natural and artificial ultramarine blue pigments using laser induced breakdown and pulsed Raman spectroscopy, statistical analysis and light microscopy. Spectroch. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 73, 525–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2008.11.028 (2009).

Zehnder, K. & Voute, A. Monitoring detaching murals in the convent of Müstair (Switzerland) by mirror micrometry. J. Cult. Herit. 10, 493–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2009.03.002 (2009).

Prieto, G. et al. The source, processing, and use of red pigment based on hematite and cinnabar at Gramalote, an early Initial Period (1500–1200 cal. B.C.) maritime community, north coast of Peru. J. Archaeol. Sci. 5, 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.10.026 (2016).

Vizarova, K. et al. Stability studies of materials applied in the restoration of a baroque oil painting. J. Cult. Herit. 12, 190–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2011.01.001 (2011).

Banait, N. S. & Jencks, W. P. General-acid and general-base catalysis of the cleavage of alpha -D-glucopyranosyl fluoride. J. Am. Chem. Soci. 113(21), 7958–7963. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00021a022 (1991).

Calvini, P. The influence of levelling-off degree of polymerisation on the kinetics of cellulose degradation. Cellulose 12(4), 445–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-005-2206-z (2005).

Lundgaard, L., Hansen, W., Linhjell, D. & Painter, T. Aging of oil-impregnated paper in power transformers. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv 19(1), 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpwrd.2003.820175 (2004).

Salem, Y. & Oudbashi, O. Eid, D 2019 Characterization of the microstructural features and the rust layers of an archaeological iron sword in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (380–500 AD). Herit Sci. 7(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-019-0261-2 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. Influence of air pollution factors on corrosion of metal equipment in transmission and transformation power stations. Atmosphere 13, 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13071041 (2022).

Emetere, M. E., Afolalu, S. A., Amusan, L. M. & Mamudu, A. Role of atmospheric aerosol content on atmospheric corrosion of metallic materials. Int. J. Corr. 2021, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6637499 (2021).

Padfield, T. et al. Back protection of canvas paintings. Herit Sci. 8, 96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00435-7 (2020).

Selwyn, L. S. Corrosion of metal artifacts in buried environments, ASM handbook, corrosion, environments and industries, ASM International. OHIO 13C, 306–322. https://doi.org/10.31399/asm.hb.v13c.a0004142 (2006).

Zheng, Y. & Liu, R. The regulation and formation for the “Eight Banners” padded armors made by Hangzhou Official Silk Factory during Qianlong period. J. Silk 55(10), 73–77 (2018).

Miao, B., Zhao, Z., Guo, P., Li, H. & Wang, Y. Cleaning iron rust compounds from cotton textiles: Application to Qing Dynasty armor. Herit. Sci. 11(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-00885-9 (2023).

Ciglanská, M., Jančovičová, V., Havlínová, B., Machatová, Z. & Brezová, V. The influence of pollutants on accelerated ageing of parchment with iron gall inks. J. Cult. Herit. 15(4), 373–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2013.09.004 (2014).

Grevey, A. L. et al. Microstructure and long-term corrosion of archaeological iron alloy artefacts. Herit. Sci. 8(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00398-9 (2020).

Frantzi, G. et al. Reversible protective and consolidating coatings for the ancient iron joints at the Acropolis monuments. Acta IMEKO 11, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.21014/actaimeko.v11i4.1341 (2022).

Koleini, F., Prinsloo, L. C., Schoeman, M. H. A., Pikirayi, I. & Chirikure, S. Characterization of the corrosion layer on iron archaeological artefacts from K2 (825–1220 AD), an archaeological site in South Africa. Stud. Conserv. 58(3), 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047058412Y.0000000044 (2013).

Odlyha, M., Thickett, D. & Sheldon, L. Minerals associated with artists’ paintings and archaeological iron objects. J. Therm. Anal Calorim. 105, 875–881. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-011-1636-0 (2011).

Neff, D., Dillmann, P., Bellot-Gurlet, L. & Beranger, G. Corrosion of iron archaeological artefacts in soil: Characterisation of the corrosion system. Corr. Sci. 47, 515–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2004.05.029 (2005).

Grevey, A. L. et al. Microstructure and long-term corrosion of archaeological iron alloy artefacts. Heritage Sci. 8, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00398-9 (2020).

Veiga, A. R Oil painting on tinplate by Francisco José Resende. Techniques, materials and degradation of three nineteenth century paintings. In: CeROArt. Conservation, exposition, Restauration d’Objets d’Art. Association CeROArt asbl. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.4000/ceroart.1775 (2010).

Burnstock, A., Van den Berg, K. J., de Groot, S., Wijnberg, L. Modern paints uncovered, proceedings from the Modern Paints Uncovered Symposium (ed. T. Learner, P. Smithen, J. Krueger and M. Schilling), 177–188. The Getty Conservation Institute. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/gci_pubs/paints_uncovered (Los Angeles, 2008).

Tumosa, C. S., Mecklenburg, M. F. Oil paints: the chemistry of drying oils and the potential for solvent disruption. In New insights into the cleaning of paintings: proceedings from the cleaning 2010 international conference, Universidad Politecnica de Valencia and Museum Conservation Institute. Smithsonian Institution. (Edited by Mecklenburg, Marion F., Charola, A. Elena, and Koestler, Robert J.) 51–58, Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation. (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2013).

Mohie, M. A., Moussa, A., Fathey, R. & Abdelaziz, S. S. Condition assessment of a mural oil painting at Fatma Ismail Palace, Agricultural Museum, Egypt. Egypt. J. Chem. 13B, 799–810. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejchem.2022.149749.6472 (2022).

Serifaki, K., Boka, H., Yalcin, S. & Ipekoglu, B. Characterization of materials used in the execution of historic oil paintings by XRD, SEM-EDS, TGA, and LIBS analysis. Mater. Character. 60, 303–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2008.09.016 (2009).

Boon, J. J. et al. Imaging microspectroscopic, secondary ion mass spectrometric and electron microscopic studies on discoloured and partially discoloured smalt in cross-sections of 16th century paintings. Chimia 55, 952. https://doi.org/10.2533/chimia.2001.952 (2001).

Carlyle, L. Reconstructions of Oil Painting Materials and Techniques: The HART Model for Approaching Historical Accuracy, in book Reconstruction, Replication and Re-enactment in the Humanities and Social Sciences . (Ed. Dupré, S., Harris, A., Kursell, J., Lulof, P., Stols-Witlox, M.) 141–168 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020).

Seves, A. M. et al. Effect of thermal accelerated ageing on the properties of model canvas paintings. J. Cult. Herit. 1(3), 315–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1296-2074(00)01078-5 (2000).

Guo, L., Wang, L. Q. & Zhao, X. Thermal aging and life prediction of silk fabrics. J. Text. Res. 41(7), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.13475/j.fzxb.20191005706 (2020).

Gordon, J., Normand, L., Bail, A., Mirabaud, S., Loeper-Attia, M., Catillon, R., Carré, A., Saheba, M., Geffroy, A., Paris, C., Bellot-Gurlet, L., Reguer, S. New strategies for the conservation of paintings on metal. in Publication Metal 2019 Proceedings of the Interim Meeting of the ICOM-CC Metals Working Group, September 2–6, (Neuchâtel) 1–9 (Switzerland, 2019).

Townsend, J., Carlyle, L., Cho, J-H., and Félix, C., M. The yellowing/bleaching behaviour of oil paint: Further investigations into significant colour change in response to dark storage followed by light exposure, (Conference: ICOM-CC 16th Triennial Meeting [postprints] At: Lisbon 2011, Publisher Critério Artes Gráficas, Lda) 1–10 (ICOM Committee for Conservation, 2011).

Gordon, J. Development of an analytical strategy for the study and preservation of painted metal objects in museum collections. Analytical chemistry. Sorbonne Université, Thèse de doctorat de Chimie Analytique, English. NNT: 2022SORUS171, 23 (2022).

Neff, D., Reguer, S., Bellot-Gurlet, L., Dillmann, P. H. & Bertholon, R. Structural characterisation of corrosion products on archaeological iron. An integrated analytical approach to establish corrosion forms. J. Raman Spectrosc. 35(89), 739–745. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.1130 (2004).

Chua, L. Whitish haze, soapy globules: Micro-analysis of degraded burmese paintings on zinc supports. Herit Sci. 7, 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-019-0287-5 (2019).

Bellot-Gurlet, L. et al. Raman studies of corrosion layers formed on archaeological irons in various media. J. Nano Res. 8, 147–156. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/JNanoR.8.147 (2009).

Reguer, S. et al. Structural evidence for the desalination of Akaganeite in the preservation of iron archaeological objects, using synchrotron x-ray powder diffraction and absorption spectroscopy. Corr. Sci. 51, 2795–2802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2009.07.012 (2009).

Kumar, K. Preservation methods of historical iron objects: An overview. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Invent. 7(3), 22–29 (2018).

Boyatzis, S. C., Velivasaki, G. & Malea, E. A. Study of the deterioration of aged parchment marked with laboratory iron gall inks using FTIR-ATR spectroscopy and micro hot table. Herit. Sci. 4, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-016-0083-4 (2016).

Karpowicz, A. Ageing and deterioration of proteinaceous media. Stud Conserv. 26(4), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1179/sic.1981.26.4.153 (1981).

Hermans, J., Keune, K., Van Loon, A. & Iedema, P. The crystallization of metal soaps and fatty acids in oil paint model systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 10896–10905. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6CP00487C (2016).

Van der Berg, J. Analytical chemical studies on traditional oil paints, PhD thesis, Faculty of Science, https://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.200950, (University of Amsterdam, 2002).

Pavlopoulou, L. C. & Watkinson, D. The degradation of oil painted copper surfaces. Stud. Conserv. 51(sup1), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1179/sic.2006.51.Supplement-1.55 (2006).

Perera, D. Y. On adhesion and stress in organic coatings. Progr. Organ. Coat. 28(1), 21–23 (1996).

Leidheiser, H. & Funke, W. Water disbondment and wet adhesion of organic coatings on metals: A review and interpretation. J. Oil Colour Chem. Associat. 70(5), 121–132 (1987).

Leo, R. F. Minerals and the visual arts. J. Geosci. Edu. 48(3), 317–320. https://doi.org/10.5408/1089-9995-48.3.317 (2000).

Saunders, D. Pollution and the national gallery. Nat. Gallery Tech. Bull. 21, 77–94 (2000).

Schnetz, K. et al. Evidence for the catalytic properties of ultramarine pigment. J. Cult. Herit. 45, 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2020.04.002 (2020).

Marszałek, M., Alexandrowicz, Z. & Rzepa, G. Composition of weathering crusts on sandstones from natural outcrops and architectonic elements in an urban environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 21, 14023–14036. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-014-3312-y (2014).

Plater, M. J. et al. The characterisation of lead fatty acid soaps in ‘protrusions’ in aged traditional oil paint. Polyhedron 22(24), 3171–3179. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-5387(03)00461-3 (2003).

Maguregui, M. et al. Multianalytical approach to explain the darkening process of hematite pigment in paintings from ancient Pompeii after accelerated weathering experiments. Anal. Methods. 6, 372–378. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ay41741g (2014).

Robinet, L., Spring, M. & Pagès-Camagna, S. Vibrational spectroscopy correlated with elemental analysis for the investigation of smalt pigment and its alteration in paintings. Anal. Meth. 5, 4628–4638. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ay40906f (2013).

Margariti, C. The application of FTIR microspectroscopy in a non-invasive and non-destructive way to the study and conservation of mineralised excavated textiles. Herit. Sci. 7(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-019-0304-8 (2019).

Garside, P. & Wyeth, P. Identification of cellulosic fibers by FTIR spectroscopy: thread and single fbre analysis by attenuated total refectance. Stud. Conserv. 48(4), 269–275. https://doi.org/10.1179/sic.2003.48.4.269 (2003).

Tudu, B. K., Sinhamahapatra, A. & Kumar, A. Surface modifcation of cotton fabric using TiO(2) nanoparticles for self-cleaning, oil-water separation, antistain, anti-water absorption, and antibacterial properties. ACS Omega. 5(14), 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b04067 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Gellan gum hydrogel as an aqueous treatment method for Xuan paper. Restaurat. Int. J. Preserv. Library Arch. Mater. 42(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1515/res-2020-0010 (2021).

Signe, V., Anu, T. & Ivo, L. ATR-FT-IR spectroscopy in the region of 550–230 cm−1 for identification of inorganic pigments. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 75(3), 1061–1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2009.12.056 (2010).

McKeown, N. K. et al. Interpretation of reflectance spectra of clay mineral-silica mixtures: Implications for martian clay mineralogy at mawrth vallis. Clays Clay Miner. 59, 400–415. https://doi.org/10.1346/CCMN.2011.0590404 (2011).

Genestar, C. & Pons, C. Earth pigments in painting: Characterisation and differentiation by means of FTIR spectroscopy and SEM-EDS microanalysis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 382, 269–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-005-3085-8 (2005).

Balakhnina, I. A. et al. Variations in the IR spectra of yellow ochre due to mixing with binding medium and drying. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 78, 183–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10812-011-9444-7 (2011).

Khabbaz, M. & Entezari, M. H. Simple and versatile one-step synthesis of FeS2 nanoparticles by ultrasonic irradiation. J. Coll. Interf. Sci. 470, 204–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2016.02.055 (2016).

Bikiaris, D. et al. Chre-differentiation through micro-Raman and micro-FTIR spectroscopies: Application on wall paintings at Meteora and Mount Athos, Greece. Spectroch. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 56, 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1386-1425(99)00134-1 (1990).

Morris, R. V. et al. Spectral and other physicochemical properties of submicron powders of hematite (alpha-Fe2O3), maghemite (gamma-Fe2O3), magnetite (Fe3O4), goethite (alpha-FeOOH), and lepidocrocite (gamma-FeOOH). J. Geophys. Res. 90(B4), 3126–3144. https://doi.org/10.1029/jb090ib04p03126 (1985).

Griffith, W.P. in: Spectroscopy of Inorganic-Based Materials (Advances in Spectroscopy) (ed. Clark. R. J. H.), Wiley Intercedence, (Chichester, 1987).

Nakamoto, K. Infrared and Raman spectra of inorganic and coordination compounds, Part A 5th edn, 153–175 (Wiley, 1990).

Calero, J. et al. Wet/dry accelerated laboratory test to simulate the formation of multilayered rust on carbon steel in marine atmospheres. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 52, 178–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/1478422X.2016.1244619 (2017).

Saragih, S., Lubis, R., Wirjosentono, B., Eddyanto. Characteristic of abaca (Musa textilis) fiber from Aceh Timur as bioplastic. in The 3rd International Seminar on Chemistry; (AIP Publishing) 2049, (New York, 2018).

Indran, S. & Raj, R. E. Characterization of new natural cellulosic fiber from Cissus quadrangularis stem. Carbohydr. Polym. 117, 392–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.09.072 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Niazy Mostafa Mohamed: Supervision & Conceptualization, Ezz Arabi Orabi: Methodology, Abdullah A. Alamri; Formal design, Abadi M. Mashlawi: Writing the draft, A. El-Shabasy: Revision and English Editing, Thanaa Ali Abo Taleb: Data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, N.M., Orabi, E.A., Alamri, A.A. et al. Effect of iron rust on color layer and structural integrity of historical oil paintings. Sci Rep 15, 15756 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84752-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84752-y