Abstract

In this study, brown macroalgae Hormophysta triquetra (HT) collected from the Qatari coast is used to biosynthesize silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) from its aqueous (AQ), chloroform: methanol (MCF), and ethanolic extracts (ET). The NPs are characterized using Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), Gas chromatography/Mass spectrometry (GC/MS) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The NPs were evaluated for their antibacterial activities by disc-diffusion method and their minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were assessed. The NPs synthesized through biological process exhibited significant antibacterial efficacy against Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas stutzeri, and Pseudomonas fragi for all the three NPs. AQ-AgNP and ET-AgNP showed higher zones of inhibition for P. fragi with inhibitory zones of 22.5 mm and 25 mm respectively. On the other hand, MCF-AgNP showed a higher zone of inhibition for E. coli with an inhibition zone of 23.5 mm. The NPs inhibited the growth of bacterial strains by deforming their structure and forming pits. The results revealed that macroalgae HT could be used as a potential candidate to produce AgNPs and have efficient antibacterial activities against both types of bacteria i.e., Gram-positive (B. subtilis and S. aureus) and Gram-negative (E. coli, P. stutzeri, and P. fragi).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, the use of NPs has tremendously increased for different purposes. NPs are in demand due to their exclusive shapes, sizes, and a larger surface area to volume. The size of NPs varies from 1 μm to 100 nm1. Metallic NPs are significantly studied due to their characteristic features such as large surface area, electrical, chemical, catalytic, and optical properties2,3. Generally, NPs are synthesized by physiochemical, electrochemical, photochemical, and heat evaporation methods that have limitations and disadvantages. These methods to synthesize NPs are costly and utilize hazardous chemicals that are toxic and have potential to harm environmental and biological entities2,4. Because of their harmful properties, the use of such NPs is restricted in biomedical field. In this context, Green nanotechnology can be regarded as an environmentally sustainable approach in which NPs are synthesized from living organisms such as plants, fungi, and bacteria5. This process is efficient both environmentally and economically6. Different types of NPs exist such as AgNPs, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), copper nanoparticles (CuNPs), and platinum nanoparticles (PtNPs)7,8. These biologically prepared metallic NPs are reported to alter the biological activities of different bacteria9 and hence, it could potentially serve as a candidate for treating bacterial infections/diseases. Recently, the biosynthesis of AgNPs has surged. The biosynthesis of AgNPs utilizes a specific concentration of metal salt silver nitrate (AgNO3). Through the bio reduction of Ag, AgNPs are biosynthesized. Ag has been utilized as a safe inorganic antimicrobial mediator with the ability to inhibit or kill 650 types of pathogenic microbes10. Studies demonstrate that AgNPs behave as strong inhibitors and develop a protective barrier against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria11. E. coli, Salmonella enteritidis, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, Candida albicans, Acinetobacter baumannii, Shigella sonnei, Micrococcus luteus, Streptococcus pyogenes, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus vulgaris are some of the species that are inhibited by AgNPs12,13,14,15,16. These inhibitory effects are achieved through neutralization of surface charge which leads to variation in the membrane permeability of bacteria leading to bacterial death17. Further, AgNPs role in production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage defense system of the cell, are responsible for anti-oxidation processes causing mechanical breaking of the membrane18. Moreover, AgNPs can pass through the bacterial biofilms and inhibit its development through gene suppression19. In aqueous medium, metallic ions from the NPs are released and absorbed through the microbial cell membranes. Consequently, the Ag+ ions interact with the protein functional groups like thiol leading to varying structural and enzymatic activities resulting in abnormal physiological events20.

Approximately 70% of the surface of Earth is oceans that have incredible biodiversity. Marine species, with their wide variety, offers exclusive advantages. Among the many available marine species, macroalgae is a crucial element of the marine ecosystem, which is considered potent for the presence of valuable secondary and biologically active compounds21. Seaweeds/macroalgae use sunlight, carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O) to synthesize carbohydrates22. Macroalgae occur in marine benthic habitats and are multicellular entities found either free-floating or bound with rocks in the marine environment23,24. They are composed of different compounds such as carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, minerals (ash), macro-minerals (Na, K, Ca, Mg, and P), and trace elements (Fe, Zn, Cu, Mn, and I)25. Macroalgae are home to significant sources of polyphenols, proteins, minerals, iodine, and vitamins. Through secondary metabolites production and adaptive mechanisms, macroalgae can survive in harsh environmental conditions that include extreme temperatures and pH, salinity and other such factors26. Different seaweeds are used to biosynthesize NPs to be utilized as antimicrobial agents. For instance, the aqueous extract of macroalgae Turbinaria conoides has been used to synthesize AgNP of 96 nm size that has shown high toxicity towards pathogenic bacterial species such as B. subtilis and K. planticola27. Comparatively, the methanolic extract of Sargassum polycystum is used to biosynthesize AgNPs of a relatively smaller size 5–7 nm. These NPs also showed inhibitory action towards human pathogens28. The sizes and shapes of NPs depend on the concentration and type of precursor used. AgNPs are mostly reported to be spherical in shape whereas other NPs where a different precursor and conditions are used can have different shapes like spherical, rectangular, triangular, and radial. Such NPs are biosynthesized from all three types of seaweed: green (Caulerpa pelteta), red (Hypnea Valentiae), and brown (S. mariocystum). Other macroalgae used to biosynthesize NPs include S. longifolium, Ulva lactuca, Corallina officinalis, Gracilaria corticate, and H. musciformis29.

In this research, HT from Qatari coast was utilized to synthesize AgNPs from the AQ, ET, and MCF extracts. To evaluate the characteristics of biosynthesized AgNPs, various spectroscopic techniques that include UV-VIS spectroscopy, TEM, FTIR and others will be used. The mechanism with which NPs work against bacterial strains will also be examined through SEM analysis. To our knowledge, this study is the first study in Qatar where macroalgal AgNPs are biologically synthesized and tested for their antibacterial potential. The findings of this research may serve as a foundation of future studies examining the composition and biological characteristics of macroalgae especially in this region.

Results

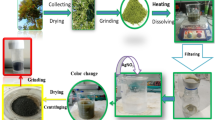

Biosynthesis of AgNPs and confirmation by UV-VIS spectroscopy

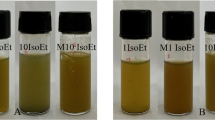

The process of AgNP formation starts when the silver source interacts with the functional groups in the extract. This reaction causes the reduction of silver, resulting in the creation of AgNPs. The first indication of biosynthesis is the color change of the initially colorless solution to a rehbraun color for AQ-AgNP (Fig. 1. A(a)). In contrast, when the colorless AgNO3 interacts with ET and MCF extract powders, it turns cloudy, with the final colors being beige for ET-AgNP and pearl-beige for MCF-AgNP (Fig. 1. A(b, c)). After visual confirmation, secondary confirmation was done by UV-VIS spectrophotometer based on the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) bands. For the three biosynthesized NPs, AQ-AgNP, ET-AgNP, and MCF-AgNP, the bands appeared at 422 nm, 423 nm, and 423 nm correspondingly as shown in Fig. 1B.

(A) Post-incubation color changes from colorless to: (a) Rehbraun for Aqueous Silver Nanoparticle (AQ-AgNP), (b) Beige for Ethanolic Silver Nanoparticle (ET-AgNP), and (c) Pearl Beige for Methanol-Chloroform Silver Nanoparticle (MCF-AgNP), (B) UV-VIS spectra analysis of AgNPs synthesized from aqueous (AQ), ethanolic (ET), methanol-chloroform (MCF) extracts, and the control AgNO3.

The pH of the biosynthesized AQ-AgNP, ET-AgNP, and MCF-AgNP were 6.5, 7.29, and 6.22 respectively. The working pH at which nanoparticles are synthesized play an important role in its stability and the reduction process of Ag. Moreover, it also assists in the antibacterial activity of the biosynthesized AgNPs30.

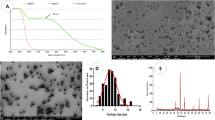

TEM analysis

TEM analysis of the extracts is shown in Fig. 2a, c and e while Fig. 2b, d and f shows the biosynthesized AgNPs. TEM analysis revealed that the AgNPs synthesized from the three types of extracts were spherical in shape with sizes varying between 10 nm and 70 nm. The image (Fig. 2b circled) indicates possible agglomeration which could be attributed to the capping process of biosynthesis of AgNPs31 while circled red in Fig. 2d and f indicates the crystalline structure and different sizes of NPs. TEM of extracts were done as a control that clearly shows irregular structure of extract used with no crystalline structures before reacting with AgNO3.

TEM images of (a) Aqueous extract (b) Aqueous Silver Nanoparticle (c) Ethanolic extract (d) Ethanolic Silver Nanoparticle (e) Methanol-chloroform extract, and (f) Methanol-Chloroform Silver Nanoparticle. Arrowed black circles indicate agglomeration of AgNPs. Red circles indicate single crystal of AgNP.

FTIR analysis

FTIR spectra of the extracts and the biosynthesized NPs are shown in Fig. 3. The differences between the peaks of crude extracts and their respective NPs indicate the involvement of those functional groups in their synthesis. Further, intensification of certain peaks in the spectra of NPs demonstrates the role of those groups in capping and stabilizing the formed AgNPs. The spectra reveal the presence of broadbands between 3000 cm− 1 to 3500 cm− 1 in both ET and MCF extracts where as in AQ extract, the region is flattened (Fig. 3, region A). On the right side of the spectra, another region B is shown with smaller peaks between 550 cm− 1 to 1700 cm− 1. These peaks correspond to aromatic functional groups, C-N, COOH, C-C, C-O, and C-O-C groups. In comparison, AQ-AgNP shows peaks at 3262.63 cm− 1, 1032.46 cm− 1, 462.87 cm− 1, and 418.46 cm− 1, 403.68 cm− 1 corresponding to O-H stretching, C-O stretching of secondary alcohols32, cycloalkane33, and alkyl halides (C-X)34. The FTIR spectra of ET-AgNP shows peaks at 3331.68 cm− 1, 2920.38 cm− 1, 2850.72 cm− 1, 1614.65 cm− 1, 1575.93 cm− 1, 1538.85 cm− 1, 1465.06 cm− 1, 1032.26 cm− 1, and 403.59 cm− 1 attributed to O-H stretch35, C-H stretching of -CH236,37, skeletal vibration of C = C38, symmetric stretching vibration of -COOH groups from amide II39, C = C stretching40, C-H bending41, C-N stretching42, C-O stretching, and alkyl halide (C-X)34. Lastly, MCF-AgNP show peaks at 3289.82 cm− 1, 3010.79 cm− 1, 2920.99 cm− 1, 2851.69 cm− 1, 1741.26 cm− 1, 1612.71 cm− 1, 1540.25 cm− 1, 1464.31 cm− 1, 1377.61 cm− 1, 1148.22 cm− 1, 1033.21 cm− 1, 822.06 cm− 1, 430.78 cm− 1, and 419.23 cm− 1 associated with O-H stretching43, CH = CH asymmetric stretching44, C-H stretching45, C-H symmetric stretching46, C = O stretching from ester group47, aromatic stretching vibrations48, C-C stretching49, C-N stretching50, COO- antisymmetric stretching51, C-O groups52, C-O-C stretching53, C-O-C asymmetric bending54, aromatic rings55, and alkyl halides34.

FTIR spectra of extracts: Aqueous (black), ethanolic (red), methanol: chloroform (blue) and silver nanoparticles: Aqueous Silver Nanoparticle (grey), ethanolic Silver Nanoparticle (pink), and methanol-chloroform Silver Nanoparticle (dark blue). Regions A and B show peaks for different functional groups.

XRD analysis

The XRD pattern of all the AgNPs are shown in Fig. 4. The diffraction peaks of AQ-AgNP at 2θ values are 28.05°, 32.45°, 38.36°, and 54.37° attributed to (011), (111), (002), and (022) (Fig. 4c) (Ref: International Center for Diffraction Data (ICDD: 98-017-4091)). ET-AgNPs indicate diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 27.98°, 32.43°, 46.38°, and 54.79°with (111), (002), (022), and (113) (Fig. 4b) (Ref: ICDD: 98-042-6932). Lastly, MCF based AgNP showed diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 28.02°, 32.43°, 46.40°, and 55.18° with (111), (002), (022), and (113) as shown in Fig. 4a (Ref: ICDD: 98-042-6932). The crystallite size of the biosynthesized AgNPs are 41.5 nm, 34.1 nm, and 59.5 nm for AQ-AgNP, ET-AgNP, and MCF-AgNP. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) values obtained for 2θ values of 32.45°, 32.43°, and 32.43° are 0.1791, 0.2175, and 0.1248 respectively. Moreover, the wavelength (\(\:\varvec{\lambda\:}\)) of x-ray used is 0.15.

GC/MS analysis

The GC/MS chromatograms showed different peaks for the NPs revealing various compounds listed in Table 1. These compounds were obtained after comparing the retention time of the peaks with those listed in the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library. Nanoparticles synthesized from AQ extract of macroalgae showed 5 peaks on the GC/MS chromatogram. The ET-AgNP GC/MS chromatogram recorded a total of 6 peaks whereas 8 peaks were found in the chromatogram of MCF-AgNP. Overall, 19 compounds were identified from the chromatograms of all the three NPs with potential antibacterial role.

XPS analysis

The XPS analysis demonstrated the composition, and oxidation states of the elements present in the biosynthesized AgNPs as shown in Fig. 5. Silver, carbon (C), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N) and sulfur (S) were analyzed by XPS analysis. In AQ-AgNP, Ag metal appeared at peaks adjacent to each other with binding energies of 366.6 eV, 367.8 eV, 372.6 eV, and 373.8 eV. The first two peaks correspond to Ag 3d5/2 while the other two peaks correspond to Ag 3d3/2. The element C shows a single peak, however, when deconvoluted, it showed four peaks close to each other at 282.2 eV, 282.3 eV, 283.7 eV, and 284.6 eV. All the peaks showed C1s attributed to the sp2 carbon configuration of C = C56. Oxygen exists in O1s which upon deconvolution showed two peaks for chemical states of O-C at 529.9 eV and O = C at 532.2 eV57. The N1s showed a peak at 398 eV which corresponds to a chemical state of -N-(C = O)-58. Moreover, for element S, two peaks were observed: S 2p3/2 at 162.5 eV and -SO3-C- at 168 eV59.

Looking at the XPS analysis of ET-AgNP (Fig. 6), the same elements were analyzed. For Ag, deconvolution showed 4 peaks at 366.2 eV, 367.8 eV, 372 eV, and 373.5 eV respectively. The first two peaks correspond to 3 d5/2 while the rest to 3 d3/2. The C1s demonstrated two peaks at 283 eV and 284 eV relating to chemical state of C = C60. The O1s spectra showed three peaks at 528.9 eV, 531 eV, and 532 eV of which two corresponds to chemical state of O-C, and the last relates to (O = C)-C61. N1s showed peaks at 393 eV, 398.8 eV, 404.5 eV, and 408.2 eV corresponding to chemical states of elemental N, azide (N*NN), nitro (-NO2), and nitrooxy (-O-NO2)62,63. XPS spectra for elemental S showed peaks at 163.7 eV, SO3 − 2 at 167.3 eV, and SO4 − 2 at 169.1 eV59.

XPS analysis of MCF-AgNP (Fig. 7) showed two distinct peaks for Ag at 365.3 eV and 371.5 eV both with chemical state of Ag 3d3/2. C1s spectra showed a single peak for C = C at 282.4 eV whereas deconvoluted O1s spectra demonstrated two peaks close to each other at 529.8 eV and 530.7 eV respectively. N1s deconvoluted spectra showed peaks at 393.4 eV for elemental N, 396.9 eV for N*NN, and 408.5 eV for -O-NO2 correspondingly63. Deconvoluted spectra of S showed peaks at 162.7 eV for S2 − 2, 166 eV for sulphinyl (R2-SO), and 170.2 eV for -S-O-63,64.

Antibacterial activity

The biosynthesized AgNPs were tested against 5 bacterial strains (Table 2). AQ-AgNP showed highest inhibition for P. fragi (22.5 mm) followed by E. coli (22 mm), P. stutzeri (19.5 mm), S. aureus (18 mm), and B. subtilis (17 mm). A similar trend was seen for ET-AgNP with maximum inhibition of P. fragi (25 mm), E. coli (24.5 mm), P. stutzeri (23.25 mm), B. subtilis (20 mm), and S. aureus (19.25 mm). Lastly, MCF-AgNP recorded the maximum inhibition for E. coli (23.5 mm), P. fragi (21.75 mm), P. stutzeri (20.5 mm), B. subtilis (20.25), and S. aureus (19 mm) respectively. Figure 8 shows the zone of inhibition for each bacterium with positive control ampicillin (Fig. 8a) and inhibition zones for the three NPs and AgNO3 (Fig. 8b). The MICs of all the bacterial strains with the three biosynthesized NPs are shown in Fig. 8c.

Further, the MIC was performed for all bacterial strains with three AgNPs, the findings are compiled in Table 2. The values of inhibition with the standard error bars are shown in Fig. 9. The MIC for E. coli for the three types of AgNP’s is 3.13 mg/mL. For both P. stutzeri and P. fragi, the MIC recorded is 0.04 mg/mL. For B. subtilis, the MIC is 0.19 mg/mL, 6.25 mg/mL, and 12.5 mg/mL for AQ-AgNP, ET-AgNP, and MCF-AgNP. For S. aureus, the MIC is 1.56 mg/mL, 0.39 mg/mL, and 1.56 mg/mL for AQ-AgNP, ET-AgNP, and MCF-AgNP respectively. Ampicillin, being an antibiotic, showed inhibition zones while AgNO3 showed inhibitory zones much smaller than the NPs indicating towards the inhibitory nature of Ag+ ions. In summary, it can be concluded that antibacterial activity of ET-AgNP is higher than the MCF-AgNP which is higher than AQ-AgNP.

Mechanism of action of bacterial inhibition

To investigate how the AgNPs react once in contact with the bacterial cells, SEM analysis was carried out. The SEM images showed clear differences between the treated (Fig. 10c-f) and untreated cells (Fig. 10a & b). Both E. coli and B. subtilis showed deformed and ruptured cells compared with controls that appeared to be smooth, integrated, and intact. At some regions in the SEM images, there are gaps and pits on the cells’ surface (marked with red arrows in Fig. 10c & d). The deformed and damaged cells are indicated by red arrows while AgNPs surrounding the bacterial cells are also found in SEM images circled black (Fig. 10e & f).

Discussion

Macroalgae is home to many biological compounds with the utmost benefits for mankind. It is imperative to analyze the different biologically active molecules and secondary metabolites that exist in seaweeds. For this purpose, in this research, three different types of solvents were used to extract bioactive compounds that were utilized to biologically synthesize NPs. Water as a solvent is the most polar which is mainly used to extract polar compounds, followed by ethanol which is used to extract compounds like tannins, polyphenols, alkaloids, flavanol, and terpenoids65. Lastly, the chloroform and methanol solvents together are used to extract lipids. In this mixed solvent, methanol acts as a disrupter breaking the strong bonds between lipids and proteins while chloroform acts as a mediator that initiates the diffusion processes and extraction of lipids from the biomass66. The extracts from macroalgae were used to synthesize NP’s that indicate the involvement of the extracted compounds in stabilizing and capping of NPs.

UV-VIS spectroscopy is a technique used as a preliminary confirmation of AgNPs synthesis. This technique is not only reliable but also easy and efficient for different metal synthesized NPs67. In the present study, the absorption peaks for AQ, ET, and MCF-NPs obtained are 422 nm, 423 nm, and 423 nm respectively. Our study aligns with other available research where the absorbance peaks of majority of the biosynthesized AgNPs are between 420 nm and 450 nm68,69. Similarly, in another study seaweeds S. polycystum, Acanthophora spicifera, and S. wightii were used to biosynthesize AgNP’s, when analyzed with UV-VIS, the peaks appeared at 424 nm, 409 nm, and 415 nm consecutively70. Furthermore, fresh and dry seaweed Codium capitatum was used to synthesize AgNPs, the UV-VIS peaks appeared at 422 nm and 425 nm71. S. cinereum was also used to synthesize AgNP and its absorption peak in UV-VIS was seen at 408 nm72. In another study, Moringa oleifera leaves were used to synthesize AgNPs with absorbance peak at 419 nm in UV-VIS spectrum2.

The stability, the efficiency of the reduction process of Ag+ during the biosynthesis of NPs, and its antimicrobial activities also depend on its working pH. In our study, the working pH of AQ, ET, and MCF-AgNP were 6.5, 7.29, and 6.22. Generally, NPs synthesized at low pH are unstable and exhibit weaker antimicrobial activities as compared with NPs synthesized at neutral and higher pH’s73. Apart from the stability, the morphology of the biosynthesized NPs is also affected by the pH of the system. For instance, a study reports the sizes of biosynthesized AgNPs to be 80 nm, less than 50 nm, and less than 35 nm at pH’s of 7, 9, and 1174. Other studies report that the acidic and neutral working pH’s help in synthesizing NPs with greater sizes and aggregation. However, some studies consider pH 7 and pH 8 to be optimum to produce AgNPs75,76. Generally, basic or alkaline conditions provide more functional group charges, thus, accelerating the reduction of Ag+ ions.

The TEM analysis showed that the biologically synthesized AgNPs have spherical shape. TEM analysis is commonly used to evaluate the morphology and size of the synthesized NPs77. Previously, our team chemically synthesized AgNPs using aqueous extract which also confirmed spherical shape of the NPs, however, the size varied between 5 nm and 50 nm42. A comparable study involving the aqueous extract of Portieria hornemannii to prepare NPs reported its size to be in range of 60–70 nm78. Other study where ethanolic extract of G. birdie was used to prepare NPs, also had sizes ranged between 20.2 and 94.9 nm79.

The functional groups present in the synthesized NPs were evaluated using FTIR analysis. FTIR analysis, nowadays, is used widely to obtain the functional groups present within the biological compounds80. The functional groups shown in the FTIR spectra correspond to the extracted compounds with possible interaction with AgNO3 to synthesize NPs and then initiate the capping and stabilizing processes. The capping agents are mainly responsible for the stability of biosynthesized NPs by controlling several factors such as their size, agglomeration, and shape. Typically, the surface energy of NPs is high leading to surface aggregation of the particles81. Efficient capping agents play a role in reducing the surface energy of NPs, hence, preventing agglomeration. In our results, the NPs synthesized from ethanolic extract showed less agglomeration as compared to aqueous and methanol: chloroform extracts making it most efficient compared to the other two extracts. In our study, the peaks in the FTIR spectra of the extracts (Fig. 3) indicates the presence of different functional groups that assists in reduction of Ag+ to Ag0 and in the capping of the biosynthesized AgNPs34,82. In AQ-AgNP, the broadband for O-H group has disappeared when compared with its control AQ extract. This means the compounds with hydroxyl functional group are involved in the reduction of Ag+. From the spectra, it can also be reported that the AQ-AgNP has no new or intense peaks which could be one of the reasons for the NPs to have less efficient capping and poor stability leading to agglomeration. This can also be confirmed and supported through the TEM analysis image (Fig. 2b) where the NPs are seen to be agglomerated. Spectra of ET-AgNP and MCF-AgNP shows intense broad bands for hydroxyl functional groups as compared to their controls denoting the involvement of this group in stabilization and capping processes of AgNPs. Similarly, functional groups labeled 1 and 3 in the FTIR spectra of ET-AgNP and MCF-AgNP intensified as compared to the controls showing that they play role in capping process and post-synthesis stability of AgNPs. Peak labelled 2, however, appeared to be slightly varied in the NPs spectra. MCF-AgNP FTIR spectrum shows a peak for hydroxyl stretch while other peaks belong to non-alcoholic functional groups indicating the presence of lipids which was expected due to the solvent (methanol: chloroform) used for extraction. The functional groups found in FTIR spectrum relate to the compounds present within the macroalgae. For instance, the presence of hydroxyl, amide, and ester groups eventually represent the existence of phenols, proteins and/or amino acids, and lipids83 in the seaweeds.

XRD analysis is a method used to gather information about the sample, including its purity, crystal size, and lattice distortion84. Generally, the XRD spectra reveals the intensity of scattered X-rays from the samples at 2θ positions. The intensity of the peaks indicates the atom number involved in scattering X-rays and the crystallinity extent of the sample. Crystallinity extent indicates the higher degree of crystallinity of the sample that is represented by a peak with greater intensity in the XRD pattern85. These crystallographic planes are characteristics of face-centered cubic (fcc) structure of metallic Ag. The samples show intense (111), and (002) reflections indicating that most NPs have a (111) and (002) plane86 (Fig. 4). All these well-defined and strong peaks confirmed that the AgNPs formed have crystalline structure based on the XRD spectra.

In this study, the NPs were characterized with various techniques. One of the techniques used is GC/MS. The GC/MS spectrums obtained for the biosynthesized NPs indicate the presence of numerous beneficial compounds. Several compounds identified in the GC/MS analysis are also reported in the literature such as Hexadecenoic acid or 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl) ethyl ester. This compound has been reported previously in the GC/MS analysis of brown macroalgae Hydroclathrus clathratus87. Compound 9-Octadecynoic acid, methyl ester has been identified previously in the methanolic extract of U. fasciata88. Other compounds such as Aromandendrene, known for its antibacterial activity89 and hexadecenoic acid and its derivatives known to exhibit additional biological activities, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties90 are also found in macroalgae. These compounds are found in the GC/MS spectra of our studied macroalgae and indicate their role in antibacterial activity of NPs. Seaweed is rich with compounds that are nutritionally significant as well as holding pharmaceutical importance. Polysterols are among the important chemical compounds that are found to be present in macroalgae. Polysterols are found in brown macroalgae with a small proportion of cholesterol91. Our GC/MS results confirmed the presence of one of the polysterols; campesterol in both ET-AgNP and MCF-AgNP spectra. Similarly, in the MCF-AgNP spectrum, peak for cholesterol has also been detected and identified. In literature, several species of seaweeds are reported to have campesterol and cholesterol such as Saccharina latissimi92, Ecklonia radiata93, Padina australis94, Porphyra dentata95, and S. piluliferum96. Polysterols are significant role players in biomedicine due to its unique antibacterial properties. For instance, cholesterol derivative compound extracted from Laurencia papillosa, a red macroalgae is known for its inhibitory action against S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, and Shigella flexineri97. Similarly, green algae, C. cylindacea has been found to have higher proportion of polysterols such as campesterol, stigmasterol and so on. These compounds are evaluated for their antibacterial properties and found to posses’ notable antibacterial activities98. Likewise, red and green macroalgae, brown macroalgae such as H. cuneiformis, Turbinaria spp, and Sargassum spp. L are also reported for their antibacterial properties. The extracts of these macroalgae revealed the presence of many polysterol compounds including the derivatives of cholesterol99. Furthermore, the presence of the listed compounds in the NPs as seen in the GC/MS spectra, indicates their involvement in the neutralization and stabilization process of AgNPs. Initially, the functional groups present in the compounds reduces and then stabilizes the NPs100. Generally, the biosynthesis of NPs occurs in three major stages: (1) the activation stage, (2) the growth stage, and (3) the termination stage. In the first step, the metal ion undergoes reduction, followed by its nucleation and the growth stage where small NPs group together to form larger NPs in line with thermodynamic stabilization. In the last stage; the termination stage, the final shape of NP is defined101. Further, these compounds contribute to the synthesis of NPs by adsorbing them on their surface. This adsorption process on the surface of NPs lead to substitution with functional groups (–OH, –NH2, –COOH, –NO2) from the active metabolites102.

To evaluate further the composition of the biosynthesized AgNPs, XPS analysis was performed. XPS is a tool primarily used to investigate the chemical nature and composition of the nanomaterials103. By knowing the chemical nature (state of oxidation) of the elements present in the NP, its interaction with the surrounding compounds or environment can be evaluated.

The antibacterial activity of AgNPs clearly demonstrates their inhibitory effect on bacteria. The precursor AgNO3 (2mM) that was used to synthesize NPs showed clear and smaller zone of inhibitions indicating the inhibitory nature of Ag+ [10] The shapes and sizes of the synthesized AgNPs are dependent on the concentration of AgNO3 used. It is reported that NPs synthesized with 5 mM AgNO3 have higher inhibitory effects than NPs synthesized with 2 mM AgNO3. AgNPs had inhibitory effects against Gram-positive such as S. aureus, and Gram-negative bacteria like E. coli which aligns with our research. AgNPs synthesized from aqueous extract of brown macroalgae, S. muticum showed inhibitory activities against B. subtilis, K. pneumoniae, and S. typhi through agar disc diffusion method. It was observed that the zone of inhibition expanded as the concentration of AgNPs104 increased. Aqueous extract of red algae, Gelidium amansii was used to synthesize AgNPs and were tested against S. aureus, B. pumilus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Aeromonas hydrophila105. Similarly, another species of genus Gelidium, G. corneum is also used for synthesis of AgNPs that inhibited the growth of E. coli106. Ethanolic extract of red algae A. specifera was used to prepare AgNPs, the efficacy of which was tested against S. aureus, B. subtilis, Salmonella spp., and E. coli. The synthesized NPs inhibited the growth of all the tested species with maximum inhibition zone for E. coli107. In a different study, AgNPs were synthesized from chloroform: methanol (1:1 v/v) extract of brown macroalgae; Spatoglossum asperum and Hedophyllum sessile. Both AgNPs were tested and proved efficient against pathogenic bacteria; Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. Citri and X. oryzae pv. oryzae108.

The mechanism through which AgNPs inhibit the growth of bacteria is controversial. It has been proposed that AgNPs either inhibit bacterial growth or kill the bacteria by harming the membrane, causing DNA damage, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), denaturing proteins, and inactivating enzymes71,109. The SEM micrographs indicates that AgNPs induced changes in the membrane of the bacterial cells effecting the transport mechanisms of bacteria leading to cell death. Some studies suggest that the AgNPs initiate bacterial cell destruction through damaging the cell membrane and then entering the inner membrane followed by the production of ROS, thus, inhibiting the cells growth110,111. Apart from generation of ROS, it is reported that inactivity of cells could also be related to the denaturation of proteins that happens when Ag+ from AgNPs bind to sulfhydryl groups of the proteins112. Furthermore, the NPs, once in contact with bacterial cells, start to accumulate on their membrane leading to structural or morphological alterations. Such alterations include cytoplasm shrinkage, membrane detachment, and cavities or pits113. There are different speculations about the effect of AgNPs on both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The presence of thick layer of peptidoglycan in Gram-positive bacteria lessen the influence of AgNPs whereas Gram-negative bacteria are affected adversely114. On the other hand, some studies suggest the opposite. In a study conducted by Premanathan and his colleagues115, Gram-positive bacteria S. aureus were affected by NPs more than the Gram-negative bacteria E. coli. Our results align with the previously mentioned result as B. subtilis had more intense cavities and pits as compared with E. coli.

Method

Chemicals

Formalin (Riedel-de Haën), Ethanol (Merck), Methanol (Merck), Chloroform (LOBA CHEMIE PVT. LTD), Silver nitrate (Scharlau), Resazurin (Signa-Aldrich), Nutrient Agar (Condalab), Nutrient Broth (HiMedia), Mueller Hinton Agar (Condalab), Glutaraldehyde (VWR), Phosphate Buffer Saline (Sigma-Aldrich).

Sample collection

Hormophysa triquetra (HT) was collected from Ad-Dukhan (25°30’10.8”N 50°50’05.4"E), Qatar in June 2023. The species were picked manually, rinsed with seawater to remove other macroalgae and debris and were relocated to lab in thermocol box.

Sample preparation

The macroalgae was washed with Milli-Q water thrice upon transferring to the laboratory and then shade dried116. After drying, the samples were grinded to obtain powder. The powder was refrigerated at 4 °C until further use. The sample of macroalgae was preserved in 4% Formalin and in dried form in the Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar.

Biosynthesis of AgNPs

To biosynthesize AgNPs, AQ, ET and MCF extracts of the macroalgae were prepared as described in the sections below:

Preparation of AQ extract

To prepare AQ extract of macroalgae, 30 g of dried macroalgal powder was added to 300 mL of sterile distilled water10 and was incubated in water bath at 60 °C for 20 min with constant shaking117. The extract was then filtered by Whatman filter paper to be used for the biosynthesis of AgNPs.

Preparation of ET extract

To prepare ET extract of macroalgae, 30 g of macroalgal powder was added to 300 mL of 70% ethanol. The mixture was kept at room temperature in a shaker at 120 rpm for 24 h. Upon completion of incubation, the extract was filtered, and another 100 mL of 70% ethanol was added to the macroalgal biomass until no further color change was observed118. The solution was filtered, and the filtrate was oven-dried at 40 °C in sterile glass plates. The extract powder was stored at − 22 °C until further use.

Preparation of MCF extract

To prepare MCF extract of macroalgae, 30 g of powder was added to 300 mL of a mixture of methanol and chloroform in a ratio of 1:2119. After the completion of sequential extraction, the extracts were oven-dried at 40 °C in sterile glass plates. The extract powder was stored at − 22 °C until further use.

Biosynthesis of AgNPs

AgNPs were prepared from all the three types of extract powders based on the procedures described in this section. For the preparation of AgNPs, 2 mM (0.34 g/L) of AgNO3 stock solution was prepared. To 20 mL of fresh AQ extract, 180 mL of 2 mM AgNO310 was added and mixed in a flask. The flask was covered with foil and was incubated at 85 °C for 24 h68. Color changes were observed at the end of incubation, and the pH was measured following which the mixtures were centrifuged for 1 h at 5000 rpm. The synthesized NPs were washed with sterile distilled water thrice to remove any residual or unbound particles70. The resultant NPs were oven-dried at 50 °C.

For the biosynthesis of AgNP from ET and MCF extract powders, 200 mg of the powders were added to 100 mL of AgNO3 solution each. The mixtures were stirred for 2 min. After the change of color, the mixtures were centrifuged for 30 min at 5000 rpm followed by washing with sterile distilled water thrice120. The NPs synthesized were oven-dried at 50 °C.

Characterization of AgNPs

To confirm the formation of AgNPs, the absorbance of the biosynthesized AgNPs were measured between the range of 200 nm to 800 nm using UV-VIS spectrometer (PerkinElmer Lambda 25 UV/VIS). AgNO3 was used as blank. TEM (Tecnai G2 TEM, TF20, FEI, Oregon, USA) was used to analyze the NPs’ structural properties. FTIR (Spectrum 400 Perkin Elmer) between the range of 400 cm− 1 to 4000 cm− 1 was used to investigate the functional groups of the NPs. Empyrean XRD device was utilized to carry out the XRD analysis that can scan the samples between the range of 5° ≤ 2θ ≤ 90°. The anode material used in the device is Cu that has a radiation of 1.5425 Å. The crystallite grain size (D) was calculated based on Debye-Sherrer Equation121:

\(\beta\:=full\:width\:at\:half\:maxima\:\left(FWHM\right)\)

\(k=Sherrer\:constant\:\)

\(\theta\:=Bragg\:diffraction\:angle\)

\(\lambda\:=wavelength\:of\:x-ray\)

GC/MS analysis was carried out to find the compounds present in NPs. For analysis, GC system 7890 A coupled with 5973 network mass-selective detector (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in scan mode with mass range between 45 and 500 m/z was used. Helium was used as a carrier gas with a flow rate of 1.50 mL/min. For sample preparation, 0.5 g of each NP was added to 1 mL of dichloromethane in an eppendorf tube. The tube was heated at 35 °C to obtain a suspension. The suspension was further diluted by adding 10 mL of dichloromethane. After mixing well, it was filtered with 0.2 μm syringe filter. About 1 µL of sample was injected into the Rxi-5Sil MS GC column (30 m, 0.32 mm ID, 0.25 μm) in a split ratio of 10:1. The column temperature was set at 80 °C and then increased to 250 °C at a rate of 15 °C per mins. The compounds were identified based on comparison with NIST 20 library.

Antibacterial activities of biosynthesized AgNPs

The antibacterial activities of AQ-AgNP, ET-AgNP, and MCF-AgNP were tested against E. coli, B. subtilis, S. aureus, P. fragi, and P. stutzeri. The bacteria were cultured on nutrient agar for 24 h. A microbial lawn of each bacterium was spread on Mueller-Hinton agar118. Sterile susceptibility discs were inoculated with 30 µL of AgNPs (50 mg/mL) and AgNO3 (2mM). Ampicillin (200 µg) was used as positive control for the experiment.

Determination of minimum inhibition concentration

The MIC of all the three NPs against five bacterial strains were determined using 96 well plate method118. Each well was inoculated with 100 uL of nutrient broth. Different concentrations of AgNP from 0.04 mg/mL to 100 mg/mL were evaluated. Wells were inoculated with bacterial suspensions and all the species were tested in triplicates. Clear media and ampicillin were used as negative and positive controls. Indicator dye resazurin (stock: 0.27 g/40 mL distilled water) was loaded in all the wells and was used to monitor the growth of bacteria. Resazurin is non-fluorescent blue dye which converts into pink-fluorescent dye upon detecting active cells122. MIC is defined as the lowest concentration where resazurin dye does not change color during incubation123. The wells were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h after which the results were recorded.

Mode of action of bacterial inhibition

To study the mode of action of bacterial inhibition by AgNPs, ET-AgNPs were used against E. coli and B. subtilis. Suspensions of both the bacterial strains along with the NPs with concentrations double the MIC values (Table 2b) were added to nutrient broth and then incubated at 37 °C in a shaking incubator at 198 rpm for 1 h. Table 3 shows the total volumes of suspension and nutrient broth added along with AgNPs.

After incubation, the cultures were centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min. For fixation steps, methodology of Amdadul Huq124 was followed with slight modification (only used 1 fixative-glutaraldehyde without using Osmium tetroxide). The pellet obtained was washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) thrice. The pellet was fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h. The sample was washed again with PBS three times followed by graded dehydration with increasing ethanol concentrations for 10 min each (25%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%). The samples were then smeared on metallic studs and then gold coated to be observed under Nova NanoSEM 450.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the macroalgal extracts can be effectively used to biologically synthesize AgNPs, which were visually confirmed by noticeable color changes and further validated by UV-VIS spectroscopy. Characterization of the AgNPs revealed a spherical shape with a size ranging between 10 nm and 70 nm. Additional studies indicated the presence of various chemical compounds with functional groups such as hydroxyl, aliphatic, aromatic, and ether groups, which play a role in the capping process of silver. The AgNPs synthesized from all extracts demonstrated antibacterial activity against the tested bacterial species, with inhibition zones ranging from 17 mm to 25 mm. The mechanism of the antibacterial activity was demonstrated by SEM analysis which showed that the NPs inhibited the growth of the bacteria by damaging the cell’s morphology. This study suggests that macroalgae could be a promising candidate for the sustainable production of AgNPs with antibacterial properties. This study will act as a baseline for any future macroalgal-based studies in Qatar for it being an eco-friendly approach for synthesis of NPs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

15 May 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article was published incorrectly under licence CC BY-NC-ND. The licence has been corrected to CC BY. Also the following information was missing from the Acknowledgement section: “Open Access funding was provided by the Qatar National Library.

References

Arya, A., Gupta, K., Chundawat, T. S. & Vaya, D. Biogenic synthesis of copper and silver nanoparticles using Green Alga Botryococcus braunii and its antimicrobial activity. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 7879403 https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7879403 (2018).

Asif, M. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), structural characterization, and their antibacterial potential. Dose-Response 20, 15593258221088709 (2022).

Sunil, T. G. et al. IntechOpen. in Silver Micro-Nanoparticles (eds Kumar Samir, Kumar Prabhat, & Pathak Chandra Shakher) Ch. 4 (2021).

Gudikandula, K. & Charya Maringanti, S. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles by chemical and biological methods and their antimicrobial properties. J. Exp. Nanosci. 11, 714–721 (2016).

Vijayaraghavan, K. & Ashokkumar, T. Plant-mediated biosynthesis of metallic nanoparticles: A review of literature, factors affecting synthesis, characterization techniques and applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 5, 4866–4883 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2017.09.026 (2017).

Nasrollahzadeh, M. et al. in Interface Science and Technology Vol. 28 (eds Mahmoud Nasrollahzadeh Elsevier, 145–198 (2019).

Schröfel, A. et al. Applications of biosynthesized metallic nanoparticles – A review. Acta Biomater. 10, 4023–4042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2014.05.022 (2014).

Singla, R., Guliani, A., Kumari, A. & Yadav, S. K. in Nanoscale Materials in Targeted Drug Delivery, Theragnosis and Tissue Regeneration 41–80 (eds Yadav, S. K.) (Springer Singapore, 2016).

Chatzimitakos, T. G. & Stalikas, C. D. Qualitative alterations of bacterial metabolome after exposure to metal nanoparticles with bactericidal properties: A comprehensive workflow based on 1H NMR, UHPLC-HRMS, and metabolic databases. J. Proteome Res. 15, 3322–3330. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00489 (2016).

Bhuyar, P. et al. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using marine macroalgae Padina sp. and its antibacterial activity towards pathogenic bacteria. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 9, 1–15 https://doi.org/10.1186/S43088-019-0031-Y (2020).

Sahayaraj, K., Rajesh, S. & Rathi, J. Silver nanoparticles biosynthesis using marine algaPadina Pavonica (LINN.) And its microbicidal activity. Digest J. Nanomater. Biostruct. (DJNB) 7 (2012).

Mukaratirwa-Muchanyereyi, N., Gusha, C., Mujuru, M., Guyo, U. & Nyoni, S. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plant extracts from Erythrina abyssinica aerial parts and assessment of their anti-bacterial and anti-oxidant activities. Results Chem. 4, 100402 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rechem.2022.100402 (2022).

Garibo, D. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Lysiloma acapulcensis exhibit high-antimicrobial activity. Sci. Rep. 10, 12805. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69606-7 (2020).

Abdellatif, A. A. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles incorporated aromatherapies utilized for their antioxidant and antimicrobial activities against some clinical bacterial isolates. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2432758 (2022).

Shaik, M. R. et al. Plant-extract-assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Origanum vulgare L. extract and their microbicidal activities. Sustainability 10, 913. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040913 (2018).

Devanesan, S. & AlSalhi, M. S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using the flower extract of Abelmoschus esculentus for cytotoxicity and antimicrobial studies. Int. J. Nanomed. 3343–3356. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S307676 (2021).

Jung, W. K. et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of the silver ion in Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 2171–2178. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02001-07 (2008).

Cheloni, G., Marti, E. & Slaveykova, V. I. Interactive effects of copper oxide nanoparticles and light to green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Aquat. Toxicol. 170, 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.11.018 (2016).

Zhao, L. & Ashraf, M. Influence of silver-hydroxyapatite nanocomposite coating on biofilm formation of joint prosthesis and its mechanism. West Indian Med. J. 64, 506. https://doi.org/10.7727/wimj.2016.179 (2015).

Girma, A. Alternative mechanisms of action of metallic nanoparticles to mitigate the global spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Cell. Surf. 10, 100112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcsw.2023.100112 (2023).

Manilal, A. et al. Bioactivity of the red algae Asparagopsis taxiformis collected from the southwestern coast of India. Braz. J. Oceanogr. 58, 93–100 (2010).

Mahmood Ansari, S. et al. Marine macroalgae display bioreductant efficacy for fabricating metallic nanoparticles: Intra/extracellular mechanism and potential biomedical applications. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5985377 (2021).

Ahmad, K. et al. Marine macroalgae polysaccharides-based nanomaterials: An overview with respect to nanoscience applications. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 11, 156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43088-022-00335-8 (2022).

Baweja, P., Kumar, S., Sahoo, D. & Levine, I. in Seaweed in Health and Disease Prevention (eds Joël Fleurence & Ira Levine) 41–106 (Academic Press, 2016).

Salehi, B. et al. Current trends on seaweeds: Looking at chemical composition, phytopharmacology, and cosmetic applications. Molecules 24, 4182. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24224182 (2019).

Wang, H. M. D., Li, X. C., Lee, D. J. & Chang, J. S. Potential biomedical applications of marine algae. Bioresour. Technol. 244, 1407–1415 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.198(2017).

Rajeshkumar, S., Kannan, C. & Annadurai, G. Synthesis and characterization of antimicrobial silver nanoparticles using marine brown seaweed Padina Tetrastromatica. Drug Invent. Today 4, 511–513 (2012).

Thangaraju, N., Venkatalakshmi, R., Chinnasamy, A. & Kannaiyan, P. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles and the antibacterial and anticancer activities of the crude extract of Sargassum polycystum C. Agardh Nano Biomed. Eng. 4, 89–94. https://doi.org/10.5101/nbe.v3i1 (2012).

Roy, S. A review: Green synthesis of nanoparticles from seaweeds and its some applications. Austin J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 7, 105 (2019).

Miranda, A., Akpobolokemi, T., Chung, E., Ren, G. & Raimi-Abraham, B. T. pH alteration in plant-mediated green synthesis and its resultant impact on antimicrobial properties of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). Antibiotics (Basel) 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11111592 (2022).

Bhole, R. et al. Superparamagnetic spherical magnetite nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and catalytic potential. Appl. Nanosci. 13, 6003–6014 (2023).

Asong, J. A. et al. Green synthesis of characterized silver nanoparticle using cullen tomentosum and assessment of its antibacterial activity. Antibiotics 12, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12020203 (2023).

Lakhmiri, H. E. F. R. & Cherkaoui, A. A. M. S. O. Removal of RR-23 dye from industrial textile wastewater by adsorption on cistus ladaniferus seeds and their biochar. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 7 (2017).

Jyoti, K., Baunthiyal, M. & Singh, A. Characterization of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Urtica dioica Linn. Leaves and their synergistic effects with antibiotics. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 9, 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrras.2015.10.002 (2016).

Yilma, B. B., Luebben, J. F. & Nalankilli, G. The effect of air, ar and O2 plasmas on the electrical resistivity and hand-feel properties of polyester/cotton blend fabric. Fibers 8, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib8020017( (2020).

Netala, V. R. et al. First report of biomimetic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Centella asiatica and their antimicrobial activity. Appl. Nanosci. 5, 801–807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-014-0374-6 (2015).

Setyaningrum, D., Riyanto, S. & Rohman, A. Analysis of corn and soybean oils in red fruit oil using FTIR spectroscopy in combination with partial least square. Int. Food Res. J. 20, 1977 (2013).

Peng, S., Fan, X., Li, S. & Zhang, J. Green synthesis and characterization of graphite oxide by orthogonal experiment. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 58, 2213–2217. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-97072013000400067( (2013).

Ashtiani, S., Khoshnamvand, M., Regmi, C. & Friess, K. Interfacial design of mixed matrix membranes via grafting PVA on UiO-66-NH2 to enhance the gas separation performance. Membranes 11, 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes11060419 (2021).

Purwasasmita, B. S., Tafwidli, F. & Septawendar, R. Synthesis and characterisation of carbon nanocoil with catalytic graphitisation process of Oryza Sativa pulp precursors. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 49, 119–126 (2013).

Yadav, D. K., Uma, S. & Nagarajan, R. Surfactant intercalation in li-al-based binary and ternary layered double hydroxides by the microwave-assisted rapid ion-exchange process and its application in Iodine adsorption. Minerals 13, 303 (2023).

Bibi, S., Bibi, A., Mullungal, M. N., Abu-Dieyeh, M. & Al-Ghouti, M. A. Macroalgae as an eco-friendly and successful green technology for the removal of crystal violet from synthetic and real wastewater. Arab. J. Chem. 16, 105191 (2023).

Pongpiacha, S. FTIR spectra of organic functional group compositions in PM2. 5 collected at Chiang-Mai City, Thailand during the haze episode in March 2012. J. Appl. Sci. 14, 2967–2977. https://doi.org/10.3923/jas.2014.2967.2977 (2014).

Faramarzi, B. et al. An FTIR Spectroscopy Investigation on different methods of lipid extraction from HepG2 cells. Eng. Proc. 27 (39). https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsa-9-13263 (2022).

Zhou, J. et al. Characteristics of chitosan-modified glass ionomer cement and their effects on the adhesion and proliferation of human gingival fibroblasts: An in vitro study. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 30, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10856-019-6240-z (2019).

Li, J. et al. Fabrication of superhydrophobic bamboo timber based on an anatase TiO2 film for acid rain protection and flame retardancy. RSC Adv. 5, 62265–62272. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA09643J (2015).

Shi, M., Gao, Q. & Liu, Y. Changes in the structure and digestibility of wrinkled pea starch with malic acid treatment. Polymers 10, 1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10121359 (2018).

Md Salim, R., Asik, J. & Sarjadi, M. S. Chemical functional groups of extractives, cellulose and lignin extracted from native Leucaena leucocephala bark. Wood Sci. Technol. 55, 295–313 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-020-01258-2(2021).

Hegde, T. A. & Vinitha, G. Chloridocobaltate(II) metal–organic cocrystal delivering intermolecular-charge transfer-enhanced passive optical limiting: A comprehensive study on structure–property relation. Eur. Phys. J. D 75 (214). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjd/s10053-021-00227-z (2021).

Patel, M. H., Chaudhuri, T. K. & Patel, V. K. Solid state in situ thermolysis approach for synthesis of PbS/PEO/PVP nanocomposite films. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 34, 667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-023-10007-7 (2023).

Deepika, K., Raghuram, M. & Bramhachari, P. Rhamnolipid biosurfactant production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain KVD-HR42 isolated from oil contaminated mangrove sediments. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 11, 218–231. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJMR2015.7881 (2017).

Thitithammawong, A., Saiwari, S., Salaeh, S. & Hayeemasae, N. Potent application of scrap from the modified natural rubber production as oil absorbent. Polymers 14, 5066. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14235066 (2022).

Ogunjobi, J. K., Adewale, A. I. & Adeyemi, S. A. Cellulose nanocrystals from Siam weed: Synthesis and physicochemical characterization. Heliyon 9, e13104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13104 (2023).

Meadows, S., Hosur, M. V., Tcherbi-Narteh, A. & Jeelani, S. A. K. in 21st International Conference on Composite Materials.

Lingegowda, D. C., Kumar, J. K., Prasad, A., Zarei, M. & Gopal, S. FTIR spectroscopic studies on cleome gynandra-comparative analysis of functional group before and after extraction. Rom. J. Biophys. 22, 137–143 (2012).

Naghdi, S. et al. The effect of cesium dopant on APCVD graphene coating on copper. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9, 9798–9812 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.06.091(2020).

Gomez-Bolivar, J. et al. Synthesis of Pd/Ru bimetallic nanoparticles by Escherichia coli and potential as a catalyst for upgrading 5-hydroxymethyl furfural into liquid fuel precursors. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1276. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01276 (2019).

Kim, H. J. et al. Synthesis and characteristics of NH 2-functionalized polymer films to align and immobilize DNA molecules. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 7, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1556-276X-7-30 (2012).

Shanthi, P. M. et al. Sulfonic acid based complex framework materials (CFM): Nanostructured polysulfide immobilization systems for rechargeable lithium–sulfur battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, A1827. https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0251910jes( (2019).

Peng, J. et al. Regulating the properties of activated carbon for supercapacitors: Impact of particle size and degree of aromatization of hydrochar. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00682-9 (2023).

Lukose, R. et al. Influence of plasma treatment on SiO2/Si and Si3N4/Si substrates for large-scale transfer of graphene. Sci. Rep. 11, 13111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92432-4 (2021).

Xie, H., Liu, G., Chen, Z., Xu, X. & Wei, C. Design of a spherical Ga2O3/ZnO composite with a snakeberry-like structure for methyl orange degradation. Water 15, 952. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15050952 (2023).

Naumkin, A. V., Kraut-Vass, A., Gaarenstroom, S. W. & Powell, C. J. (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2000).

Zhang, Y. et al. Sulfurized hematite for photo-Fenton catalysis. Progress Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 27, 443–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnsc.2017.08.006 (2017).

Jha, A. K. & Sit, N. Extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials using combination of various novel methods: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 119, 579–591 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.11.019(2022).

Saini, R. K., Prasad, P., Shang, X. & Keum, Y. S. Advances in lipid extraction methods—A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 13643. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413643( (2021).

Tomaszewska, E. et al. Detection limits of dls and UV-vis spectroscopy in characterization of polydisperse nanoparticles colloids. J. Nanomater. 313081. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/313081 (2013).

Koçer, A. T. & Özçimen, D. Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles from macroalgae: Optimization, characterization and antimicrobial activity. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery, 1–12 (2022).

Bhakya, S., Muthukrishnan, S., Sukumaran, M. & Muthukumar, M. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their antioxidant and antibacterial activity. Appl. Nanosci. 6, 755–766 (2016).

Thiurunavukkarau, R. et al. Silver nanoparticles synthesized from the seaweed Sargassum polycystum and screening for their biological potential. Sci. Rep. 12, 14757. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18379-2 (2022).

Algotiml, R. et al. Anticancer and antimicrobial activity of biosynthesized Red Sea Marine algal silver nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 12, 2421. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06412-3 (2022).

Mohandass, C. et al. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from marine seaweed Sargassum Cinereum and their antibacterial activity. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 75, 606 (2013).

Fahim, M. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: A comprehensive review of methods, influencing factors, and applications. JCIS Open. 16, 100125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jciso.2024.100125 (2024).

Nurfadhilah, M., Nolia, I., Handayani, W. & Imawan, C. The role of pH in Controlling size and distribution of silver nanoparticles using biosynthesis from Diospyros discolor Willd. (Ebenaceae). IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 367 (012033). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/367/1/012033 (2018).

Iqtedar, M. et al. Extracellular biosynthesis, characterization, optimization of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using Bacillus mojavensis BTCB15 and its antimicrobial activity against multidrug resistant pathogens. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 49, 136–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826068.2018.1550654 (2019).

Elsayed, M. A., Othman, A. M., Hassan, M. M. & Elshafei, A. M. Optimization of silver nanoparticles biosynthesis mediated by Aspergillus Niger NRC1731 through application of statistical methods: Enhancement and characterization. 3 Biotech. 8, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-018-1158-6 (2018).

Lin, P. C., Lin, S., Wang, P. C. & Sridhar, R. Techniques for physicochemical characterization of nanomaterials. Biotechnol. Adv. 32, 711–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.11.006 (2014).

Fatima, R., Priya, M., Indurthi, L., Radhakrishnan, V. & Sudhakaran, R. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using red algae Portieria Hornemannii and its antibacterial activity against fish pathogens. Microb. Pathog. 138, 103780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103780 (2020).

de Aragão, A. P. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using the seaweed Gracilaria birdiae and their antibacterial activity. Arab. J. Chem. 12, 4182–4188 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2016.04.014 (2019).

Song, Y., Cong, Y., Wang, B. & Zhang, N. Applications of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to pharmaceutical preparations. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 17, 551–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425247.2020.1737671 (2020).

Restrepo, C. V. & Villa, C. C. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles, influence of capping agents, and dependence on size and shape: A review. Environ. Nanatechnol. Monit. Manag. 15, 100428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enmm.2021.100428 (2021).

Essghaier, B. et al. Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from the extremophile plant aeonium haworthii and their antioxidant, antimicrobial and anti-diabetic capacities. Nanomaterials 13, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13010100 (2022).

Gangidi, R. R., Proctor, A. & Meullenet, J. F. Milled rice surface lipid measurement by diffuse reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (DRIFTS). J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 79, 7–12 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11746-002-0427-4 (2002).

Magdy, G., Aboelkassim, E., Abd Elhaleem, S. M. & Belal, F. A comprehensive review on silver nanoparticles: Synthesis approaches, characterization techniques, and recent pharmaceutical, environmental, and antimicrobial applications. Microchem. J. 196, 109615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2023.109615 (2024).

Eldos, H. I., Khan, M., Zouari, N., Saeed, S. & Al-Ghouti, M. A. Adsorptive removal of volatile petroleum hydrocarbons from aqueous solution by zeolite imidazole framework (ZIF-8) and iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles. Environ. Technol. Innov. 32, 103382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2023.103382 (2023).

Ali, M. H. et al. Analysis of Crystallographic structures and properties of Silver nanoparticles synthesized using PKL Extract and Nanoscale characterization techniques. ACS Omega 8, 28133–28142. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c01261 (2023).

Ahmed, S. A., Rahman, A. A., Elsayed, K. N. & Ahmed, S. A. Comparative biological studies, phytochemical screening and GC-MS analysis of some Egyptian Red Sea macroalgae. Int. J. Pharm. Res. (09752366) 12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11696-023-03217-0 (2020).

Shobier, A. H., Ghani, A. & Barakat, K. M. S. A. GC/MS spectroscopic approach and antifungal potential of bioactive extracts produced by marine macroalgae. Egypt J. Aquat. Res. 42, 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejar.2016.07.003 (2016).

Palazzo, M. C. et al. Chemical compositions and biological activities of leaf essential oils of six species of Annonaceae from Monteverde, Costa Rica. Rec. Nat. Prod. 3, 153–160 (2009).

Mohammed, G. J. & Al, M. J. Anti-bacterial, antifungal activity and chemical analysis of punica grantanum (Pomegranate peel) using GC-MS and FTIR spectroscopy. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 8 (2016).

Sohn, S. I. et al. Phytosterols in seaweeds: An overview on biosynthesis to Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222312691 (2021).

de Jong, D. L., Timmermans, K. R., de Winter, J. M. & Derksen, G. C. Effects of nutrient availability and light intensity on the sterol content of Saccharina latissima (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae). J. Appl. Phycol. 33, 1101–1113 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-020-02359-y(2021).

Saini, R. K., Mahomoodally, M. F., Sadeer, N. B., Keum, Y. S. & Rengasamy, K. R. Characterization of nutritionally important lipophilic constituents from brown kelp Ecklonia radiata (C. Ag.) J. Agardh. Food Chem. 340, 127897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127897 (2021).

Akbary, P. et al. Sterol and fatty acid profiles of three macroalgal species collected from the Chabahar coasts, southeastern Iran. Aquacult. Int. 29, 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10499-020-00616-y (2021).

Kazłowska, K., Lin, H. T. V., Chang, S. H. & Tsai, G. J. In vitro and in vivo anticancer effects of sterol fraction from red algae Porphyra dentata. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/493869 (2013).

Ito, M. et al. Analysis of functional components and radical scavenging activity of 21 algae species collected from the Japanese coast. Food Chem. 255, 147–156 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.02.070 (2018).

Kavita, K., Singh, V. K. & Jha, B. 24-Branched ∆5 sterols from Laurencia papillosa red seaweed with antibacterial activity against human pathogenic bacteria. Microbiol. Res. 169, 301–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2013.07.002 (2014).

Bakar, K., Mohamad, H., Tan, H. S. & Latip, J. Sterols compositions, antibacterial, and antifouling properties from two Malaysian seaweeds: Dictyota dichotoma and Sargassum Granuliferum. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 9, 047–053. https://doi.org/10.7324/japs.2019.91006 (2019).

Rahelivao, M. P., Gruner, M., Andriamanantoanina, H., Bauer, I. & Knölker, H. J. Brown algae (Phaeophyceae) from the coast of Madagascar: Preliminary bioactivity studies and isolation of natural products. Nat. Prod. Bioprospecting 5, 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13659-015-0068-0 (2015).

Zuhrotun, A., Oktaviani, D. J. & Hasanah, A. N. Biosynthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using phytochemical compounds. Molecules 28, 3240. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28073240 (2023).

Makarov, V. et al. Green nanotechnologies: Synthesis of metal nanoparticles using plants. Acta Naturae (англоязычная версия) 6, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1039/C1GC15386B (2014).

Khan, S. A., Shahid, S. & Lee, C. S. Green synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using leaf extract of Clerodendrum inerme; characterization, antimicrobial, and antioxidant activities. Biomolecules 10, 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10060835 (2020).

Krishna, D. N. G. & Philip, J. Review on surface-characterization applications of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS): Recent developments and challenges. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 12, 100332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsadv.2022.100332 (2022).

Madhiyazhagan, P. et al. Sargassum muticum-synthesized silver nanoparticles: An effective control tool against mosquito vectors and bacterial pathogens. Parasitol. Res. 114, 4305–4317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-015-4671-0 (2015).

Pugazhendhi, A., Prabakar, D., Jacob, J. M., Karuppusamy, I. & Saratale, R. G. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Gelidium amansii and its antimicrobial property against various pathogenic bacteria. Microb. Pathog. 114, 41–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2017.11.013 (2018).

Yılmaz Öztürk, B., Yenice Gürsu, B. & Dağ, İ. Antibiofilm and antimicrobial activities of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using marine red algae Gelidium corneum. Process. Biochem. 89, 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2019.10.027 (2020).

Ibraheem, I., Abd-Elaziz, B., Saad, W. & Fathy, W. Green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using marine Red Algae Acanthophora specifera and its antimicrobial activity. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 7, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7439.1000409 (2016).

Jothirethinam, A., Prathiba, S., Shanthi, N. & Arunkumar, K. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles prepared from the antimicrobial crude extracts of two brown seaweeds against plant pathogens. Am. J. Nanatechnol. 6, 31 https://doi.org/10.3844/ajnsp.2015.31.39 (2015).

Hamedi, S., Ghaseminezhad, M., Shokrollahzadeh, S. & Shojaosadati, S. A. Controlled biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using nitrate reductase enzyme induction of filamentous fungus and their antibacterial evaluation. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 45, 1588–1596. https://doi.org/10.1080/21691401.2016.1267011 (2017).

Li, W. R. et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of silver nanoparticles on Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85, 1115–1122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-009-2159-5 (2010).

Balaraman, P. et al. Phyco-synthesis of silver nanoparticles mediated from Marine Algae Sargassum myriocystum and its potential Biological and Environmental Applications. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 11, 5255–5271. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12649-020-01083-5/FIGURES/11 (2020).

Siddiqi, K. S., Husen, A. & Rao, R. A. K. A review on biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and their biocidal properties. J. Nanobiotechnol. 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-018-0334-5 (2018).

Sondi, I. & Salopek-Sondi, B. Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agent: A case study on E. Coli as a model for Gram-negative bacteria. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 275, 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2004.02.012 (2004).

Manzoor, S. et al. Biofabricated platinum nanoparticles: Therapeutic evaluation as a potential nanodrug against breast cancer cells and drug-resistant bacteria. RSC Adv. 11, 24900–24916. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1RA03133C (2021).

Premanathan, M., Karthikeyan, K., Jeyasubramanian, K. & Manivannan, G. Selective toxicity of ZnO nanoparticles toward Gram-positive bacteria and cancer cells by apoptosis through lipid peroxidation. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 7, 184–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2010.10.001 (2011).

Kumar, P., Senthamil Selvi, S. & Govindaraju, M. Seaweed-mediated biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Gracilaria corticata for its antifungal activity against Candida Spp. Appl. Nanosci. 3, 495–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-012-0151-3 (2013).

Princy, K. F. & Gopinath, A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using polar seaweed Fucus Gardeneri and its catalytic efficacy in the reduction of nitrophenol. Polar Sci. 30, 100692–100692. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.POLAR.2021.100692 (2021).

Saleh, I. & Abu-Dieyeh, M. H. Novel Prosopis juliflora leaf ethanolic extract coating for extending postharvest shelf-life of strawberries. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108641 (2021).

Kehelpannala, C. et al. A comprehensive comparison of four methods for extracting lipids from Arabidopsis tissues. Plant. Methods 16, 155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13007-020-00697-z (2020).

Abdel-Raouf, N., Al-Enazi, N. M., Ibraheem, I. B. M., Alharbi, R. M. & Alkhulaifi, M. M. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by using of the marine brown alga Padina pavonia and their characterization. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 26, 1207–1215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.01.007 (2019).

Patra, N., Kar, D., Pal, A. & Behera, A. Antibacterial, anticancer, anti-diabetic and catalytic activity of bio-conjugated metal nanoparticles. Adv. Nat. Sci. NanoSci. NanoTechnol. 9, 035001. https://doi.org/10.1088/2043-6254/aad12d (2018).

Costa, P., Gomes, A., Braz, M., Pereira, C. & Almeida, A. Application of the Resazurin cell viability assay to Monitor Escherichia coli and Salmonella Typhimurium inactivation mediated by phages. Antibiot. (Basel) 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10080974 (2021).

Stefanović, O. D., Tešić, J. D. & Čomić, L. R. Melilotus albus and Dorycnium herbaceum extracts as source of phenolic compounds and their antimicrobial, antibiofilm, and antioxidant potentials. J. Food Drug Anal. 23, 417–424 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfda.2015.01.003 (2015).

Huq, M. A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Pseudoduganella Eburnea MAHUQ-39 and their antimicrobial mechanisms Investigation against Drug Resistant Human pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1510 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Central Laboratory Unit (CLU), Qatar University for TEM and FTIR analysis, Mr. Abdulla Al Ashraf of Center for Advanced Materials (CAM), Qatar University for XRD analysis, Eng. Ahmed Mohamed Soliman of Gas Processing Center (GPC), Qatar University for XPS analysis. GC/MS analysis was accomplished in the Environmental Science Center (ESC), Qatar University by Ms. Thoraya Haidar S A Alyafei. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Nabil Zouari (Professor, Qatar University) for providing bacterial strains, Mr. Zahid Shah (Health Safety and Environmental Engineer at Petroleum Technology, Qatar) and Dr. Nayeem Mullungal (Teaching Assistant, Qatar University) for their contribution in seaweed sampling. This research was made possible by Qatar University Graduate Assistantship Program. The statements made herein are solely the responsibility of the author(s).

Funding

Open Access funding was provided by the Qatar National Library.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Validation, Writing- Original draft preparation. MHA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Software, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. MAG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Validation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bibi, S., Abu-Dieyeh, M.H. & Al-Ghouti, M. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from macroalgae Hormophysa triquetra and investigation of its antibacterial activity and mechanism against pathogenic bacteria. Sci Rep 15, 2476 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84760-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84760-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Phyto-Assisted Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) Using Delonix elata Extract: Characterization, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Photocatalytic Activities

Molecular Biotechnology (2025)

-

Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) as a Double-Edged Sword: Synthesis, Factors Affecting, Mechanisms of Toxicity and Anticancer Potentials—An Updated Review till March 2025

Biological Trace Element Research (2025)

-

Eco-friendly fabrication of silver nanoparticles via Acacia mangium: Exploring antioxidant and antibacterial potentials

Chemical Papers (2025)

-

A Comprehensive Review of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs): Synthesis Strategies, Toxicity Concerns, Biomedical Applications, AI-Driven Advancements, Challenges, and Future Perspectives

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2025)