Abstract

Aromatic π-complexes play a significant role in various chemical and biological systems, significantly influencing their physico-chemical and spectroscopic properties. The identification of new compounds capable of π-complex formation is therefore of great interest. The paper investigates the fluorescent properties of 1,5-diisocyanonaphthalene (1,5-DIN) in different aromatic solvents, demonstrating its potential for distinguishing between aromatics based on emission spectra. The resulting spectra can be classified as benzene-, toluene-, and xylene-like types and may be used for the fingerprint identification of benzenes with different electron donating/withdrawing substituents. Comparative studies with related compounds revealed that lower electron density in the naphthalene core favors π-complex formation. The study also found that electron-donating groups in solvents caused more significant redshifts, while electron-withdrawing groups had minimal impact. High-level DFT calculations supported these observations, showing that stronger π-π interactions lead to greater redshifts, particularly in solvents, such as toluene and xylenes. The research suggests that 1,5-DIN’s distinct emission behaviors can be leveraged for compositional analysis of benzene-toluene-xylene (BTX) mixtures, with specific emphasis on the influence of electron density and solvent interactions on the emission properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aromatic π-complexes are molecular structures formed through interactions involving aromatic compounds, characterized by the presence of π-electron systems. These complexes arise from various interactions, including cation − π interactions1 and π-π stacking2, which are crucial in both environmental and combustion chemistry. Their unique structural and electronic properties facilitate improved charge transport (CT) and light emission efficiency therefore aromatic π-complexes have diverse practical applications, particularly in organic electronics3,4, such as organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs)5,6, photovoltaic cells7,8, and field-effect transistors (OFETs)9. They also find important applications in environmental science10,11, and catalysis. Aromatic π-complexes play a crucial role in the self-assembly of various molecular structures, leveraging non-covalent interactions to form stable supramolecular architectures. This process is significant in the development of functional materials and nanostructures. Aromatic π-π stacking interactions play a crucial role in directing and regulating the self-assembly of peptide nanostructures, contributing to the stability and functionality of the resulting nanoassemblies12.

Aromatic interactions are pivotal in creating materials with specific properties, such as molecular tweezers that exhibit stimuli-responsive behavior13 or controlling the morphology of self-assembled metal complex structures14,15.

In aromatic π-complexes non-covalent interaction occurs between a π-donor and a π-acceptor moiety. For instance, benzene derivatives armed with electron donating groups (EDG), pyridine, and other electron rich polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) function as π-donors by availing their electron cloud for interaction. Aromatic nitro compounds, quinones or any other electron-deficient species like transition metal ions or metal complexes can act as π-acceptors in this case16. The stability and structure of π-complexes are influenced by both π-π electron and electrostatic interactions, which arise from partial charges in the aromatic molecules. While π-electron clouds primarily drive these non-covalent interactions, electrostatic forces add significant stabilization, especially with notable electronegativity differences. Depending on the orientations and electronic properties of the aromatics, π-complexation can occur through face-to-face (π-π) stacking, T-shaped interactions, or edge-to-face arrangements17,18,19,20.

Face-to-face stacking involves parallel alignment of aromatic rings with strong π-π interactions, T-shaped interactions occur when one molecule is perpendicular to another’s π-system (typical for benzene), and edge-to-face arrangements involve alignment of one molecule’s edge with another’s face2. Face-centered π-stacking grabs the most attention, due to its commonness and importance as was demonstrated previously. In this arrangement the overlap is maximal and results in robust non-covalent interactions usually between electron-rich aromatic molecules and electron-deficient partners, in aromatic donor-acceptor interactions21. In addition to their geometry and electronic nature of aromatic molecules, their size, shape and ring substitution pattern impact stability, strength of interactions and orientation. Solvents, counterions and co-solutes modulate more the aromatic interactions, affecting overall pi-complex stability.

Detection and quantification of aromatic analytes is frequently based on the π-complexation, applying UV-visible, fluorescence spectroscopy and electrochemical methods that exploit the influenced electronic transitions or optical properties22,23,24,25. Various sensors and chemosensors also use π-complexation for selective and sensitive determination of aromatic analytes in environmental samples or pharmaceuticals as well as biological molecules26. Based on the above the search for novel aromatic moieties capable of forming strong π-π stacking interactions is of great importance from both scientific and practical points of view.

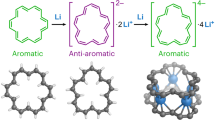

Our group presented pioneering work in the field of aromatic isocyanoaminoarenes. Previously, we demonstrated that 1-amino-5-isocyanonaphthalene (ICAN) forms a fluorescent π-complex with pyridine27. This may explain the unique quenching behavior of naphthylamines in pyridine, where following an almost complete quenching with increasing amount of pyridine the residual (10%) fluorescence is the result of the presence of a π-stacked complex between pyridine and ICAN. More recently, we discovered that the very related 1,5-diisocyanonaphthalene (1,5-DIN) is a potent antifungal even against multiresistant Candida28 and Fumigatus29 strains that pose serious threat during viral pandemics such as SARS-CoV-19. For deeper understanding, its mechanism of action was investigated by its photophysical behavior in different media30 and it was observed that unlike for most organic solvents, in aromatic media, the spectra changed significantly.

In the present study, we demonstrate that 1,5-DIN owing to its electron deficient aromatic ring readily forms π-π complexes with selective electron rich benzene derivatives, such as xylene, resulting specific changes in their fluorescent spectra, offering the possibility for analytical applications or for the design of novel self-assembled systems based on π-stacking. The complex formation and the spectroscopic characteristics were explored by quantum chemical method at M06-2X/6-311G++(2d,2p)[PCM(MeCN)].

Results and discussion

Proof of aromatic complex formation with 1,5-diisocyanonaphthalene (1,5-DIN)

Previously we demonstrated that 1,5-diisocyanonaphthalene (1,5-DIN) has the potential to become a versatile and powerful fluorescent probe30. Due to its symmetric structure, including two strongly electron withdrawing isocyano groups on the naphthalene core at 1,5 positions, the shape and the position of the emission peaks change little in solvents of different polarity (Fig. 1a). In most solvents, the original double peak with maxima at approximately 330 and 345 nm can be identified. However, in toluene the spectrum changes dramatically. Instead of two peaks, only one broad peak appears at 354 nm with a shoulder at 340 nm. The broadening and significant redshift of the emission peak may suggest the presence of specific interactions such supposed as π-π stacking. To test this assumption, UV-Vis and steady-state emission spectra were recorded in common aromatic solvents, such as benzene, toluene and p-xylene, as shown in Fig. 1b-c. The UV-Vis spectra (Fig. 1b) are almost identical in benzene, toluene and p-xylene. The most intense absorption peak is found at 303–304 nm with molar extinction coefficients (ε) varying between 9500 and 10,700 M-1cm-1. Two lower intensity peaks are also found at lower energies, at 317 and 329 nm, respectively. For fluorescence studies we used the absorption band at 317 nm as excitation wavelength to reduce the possible overlap with the absorption of the pure aromatic solvents near 300 nm. Unlike the absorption spectra, the emission spectra differ significantly. In benzene, the original double peak structure is retained, however, the two peaks have almost the same intensity, broadening of the peaks and a slight redshift of 8 and 3 nm (from 330 to 338 nm and from 345 to 348 nm) can also be observed. More pronounced bathochromic shift is identified in the case of toluene. Only one broad peak at 354 nm (∆λem, max=9 nm) with a left shoulder at 341 nm appears, it may be the remnant of the higher energy peak of the doble peak structure. Upon the addition of p-xylene, the emission spectrum changes significantly, as only single broad charge transfer (CT) like emission band is found with a maximum of 380 nm, which is red-shifted by 35 nm and 26 nm relative to those observed in MeCN and in toluene, respectively. Similarly, to the bathochromic shift of the emission maximum, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) values also increase from benzene, toluene to xylene and were found to be 39 nm, 50 nm, and 61 nm, respectively (Table 1).

For comparison, we recorded the emission spectra of the starting material 1,5-diaminonaphthalene (DAN) and the unsymmetrical 1-isocyano-5-aminonaphthalene (ICAN) in benzene, toluene and p-xylene (Fig. 1d). Surprisingly, no effect could be observed for DAN, since all three normalized spectra perfectly overlap. However, a miniscule effect is observable in the case of ICAN, and interestingly the order of bathochromic shifts is reversed, that is the emission spectrum recorded in benzene can be found at a few nm higher than those recorded in toluene or p-xylene. It may be concluded that the aromatic interaction is in connection with the electron density of the naphthalene core in the order of DIN, ICAN and DAN, showing that lower electron density is more favored for π-complex formation.

(a) The emission spectra of 1,5-diisocyanonaphthalene (1,5-DIN) in solvents of different polarity. (b) The UV-vis absorption spectra and (c) emission spectra of 1,5-DIN in benzene, toluene and p-xylene. (d) The normalized emission spectra of 1,5-diaminonaphthalene (DAN) and 1-isocyano-5-aminonaphthalene (ICAN) in benzene, toluene and p-xylene. ([DIN] = 1.25 × 10− 5 M, [DAN] = 1.197 × 10− 5 M, [ICAN] = 1.197 × 10− 5 M, T = 20 °C, λex, DIN = 317 nm, λex, DAN = 333 nm, λex, ICAN = 340 nm).

Optical characterization of 1,5-diisocyanonaphthalene (1,5-DIN) in various aromatic solvents

To gain quantitative insight into the aromatic complex formation of 1,5-DIN, UV-Vis and steady state emission spectra were recorded in a number of different aromatic solvents (Fig. 2), selected to cover a wide range of electron donating ability. It should be noted that the emission spectrum of each pure solvent was also recorded to exclude the presence of any fluorescent impurities. The emission spectra are presented in Fig. 2a–d, and the results are collected in Table 1.

It is evident from Fig. 2a that each aromatic solvent has a unique effect on the emission properties of 1,5-DIN, however, some general conclusions can also be drawn. The higher the electron density on the aromatic ring of the solvent, the higher the bathochromic shift of the emission maximum. For example, in the case of trifluorotoluene (Fig. 2a, black line), having strong EWG, no redshift and no change in the shape of the emission spectrum compared to that of in acetonitrile could be observed (Fig. 2a, dashed line). It is also apparent, analogously to Fig. 1c, that three distinct type of emission bands can be identified in Fig. 2b-d, such as benzene-, toluene- and xylene-type emissions. Benzene type emission (Fig. 1c left and Fig. 2b) can be characterized by the presence of two peaks located at 345 and 348 nm, including benzene, benzonitrile, chlorobenzene and ortho-dichlorobenzene (ODCB) as solvents. Bromo- and iodobenzene would possibly belong to this group, however, complete quenching of 1,5-DIN fluorescence could be observed most probably due to the well-known heavy atom effect31.

The second group is the toluene-type, including toluene, ethylbenzene, benzyl chloride and benzyl alcohol. The emission spectrum in this group is characterized by a broad emission band with a maximum located at 354–356 nm (Fig. 2c) and a slight shoulder at 340 nm (29 400 cm-1), which can be the remainder of the higher energy peak of the benzene type emission (Fig. 2b) at λem = 338–340 nm.

The third type emission is the xylene-type, which includes o-, m-, p-xylene and mesitylene, i.e. benzene derivatives substituted with at least two EDG as alkyl substituents. In this case the emission spectrum contains only one, strongly redshifted broad band with λem, max = 373–374 nm (26 800 − 26 740 cm-1) for mesitylene and o-xylene. Interestingly, the emission maximum of the meta isomer is found at the highest energy λem, max = 365 nm (27 400 cm-1). The highest redshift is observed for p-xylene, with λem, max = 380 nm (26 300 cm-1) as maximum, almost 10 nm higher, than that of o-xylene, indicating some kind of specific interaction between p-xylene and 1,5-DIN.

The emission spectra of 1,5-diisocyanonaphthalene (1,5-DIN) recorded in different aromatic solvents (a). The spectrum recorded in acetonitrile (MeCN, dashed line) was included for comparison. The normalized emission spectra of 1,5-diisocyanonaphthalene (1,5-DIN) recorded in aromatic solvents. ([1,5-DIN] = 1.25 × 10− 5 M, T = 20 °C, λex, DIN = 317 nm, V = 3.00 cm3).

Theoretical results

The experimental results showed a significant red shift in the emitted spectra in the presence of different xylene derivatives and mesitylene compared to other substituted benzenes, which should be studied on theoretical level, as well. This phenomenon can be explained by the formation of a strong π-π interaction between 1,5-DIN and the phenyl ring of the solvent molecule. In this way mono- (Complex-I) and bis-complexes (Complex-II) were optimized with parallel arrangement at ground (S0) and excited states (S1) states at M06-2X/6-311G++(2d,2p)[PCM(MeCN)] level of theory. The so-called T-arrangement, where the phenyl ring is perpendicular to the plane of the naphthalene, proved to be not relevant in either case. Two aspects were studied during the complexation. At first, we calculated the excitation (λex) and the emitted wavelengths (λem) of the various complexes A and B (Fig. 3; Table 2). Secondly, we calculated the enthalpies of the complex formation [ΔH(A) and ΔH(B)]. These enthalpies were corrected by an arbitrary reference complexation reaction of 1,5-DIN and hexane, which does not involve the π-π interaction [ΔΔH(A) and ΔΔH(B)]. If one studies the calculated emitted wavelengths, in all the cases the λem shifted to red by 10–20 nm for Complex-I and 20–30 nm for Complex-II. It should be mentioned, that the highest red shift is predicted for toluene, the o,m,p-xylenes and mesitylene, in agreement with the observations. However, the calculated emission for example for benzene has similar red shift such as others, contrary with the experiment. For the complete picture, we should consider the complexation enthalpies as well. The highest ΔΔH(I) and ΔΔH(II) values were exhibited by m and p-xylenes as well as Ph–Cl (Table 2). The least interaction is predicted for pyridine and benzene, which explain the observed weak red shift in these solvents.

In the structure of the π-π Complex-I, the phenyl ring placed in a non-central position above and under one of the rings of the naphthalene plane in a parallel arrangement. According to the calculated Mulliken charges separated to 1,5-DIN and the solvent molecule upon the complex formation, significant amount of negative charge is placed from the phenyl ring to the 1,5-DIN, as illustrated in Fig. 4 left side. Just as an example for Complex-I, this charge shift is − 0.032 for benzene, − 0.045 for toluene, while–0.078 for p-xylene (Fig. 4 right). This trend is in a good correlation with the general expectation that EDGs provide more electron density toward the electron deficient ring of 1,5-DIN. Upon excitation, the charge shift from phenyl ring toward naphthalene ring increases by 0.01 in all the three cases, which is considerable.

This charge transfer and the merged π-π electron system can be understood by the HOMO orbital of the Complex-I (Fig. 5). In the case of p-xylene, toluene and benzene complex, the HOMO and HOMO–1 orbitals are the strong composition of the former two HOMOs of aromatic ring as well as 1,5-DIN, referring to a merged electron system. In the first order excitation, these HOMO and HOMO-1 are involved. In contrast to the EDGs such as Me, the EWGs such as CF3 and CN result an electron deficient aromatic phenyl ring, which is already not able to provide electron density toward the also electron deficient naphthalene, which minimize the interaction between the two molecules (Fig. 5). Interestingly, in the LUMO there is no similar overlap between the two LUMOs, as shown in Fig. 5.

Top left: The π-π complex formation of 1,5-DIN with a substituted phenyl ring for Complex-I and II. Bottom left: The reference complexation reaction with non-aromatic cyclohexane. Right: Comparison of computed corrected enthalpies [ΔΔH(I); [ΔΔH(II)] for the mono and binary complexation of 1,5-DIN and some substituted phenyl derivatives at M06-2X/6-311G++(2d,2p)[PCM(MeCN)] level of theory. A = benzene; B = pyridine; C = toluene; D = o-xylene; E = m-xylene; F = p-xylene; G = mesitylene; H = Ph–CF3; I = Ph–CN; J = Ph–Cl; K = Ph–CH2OH;

Analytical applicability of p-complex formation

The different complexation strength and the accompanying spectral changes may be utilized in compositional analysis of the industrially very important benzene-toluene-xylene (BTX) fractions. To confirm this assumption, small amounts of p-xylene were added to the dilute solution of 1,5-DIN in benzene or toluene and fluorescence spectra were recorded using the common excitation wavelength of λex = 317 nm (Fig. 6).

Spectral changes upon the addition of p-xylene into the benzene (A) and toluene (B) solution of 1,5-DIN. The (C) figure demonstrates spectral changes when toluene is added into the benzene solution of 1,5-DIN. Each line corresponds to the addition of 10 µL of p-xylene or toluene. ([1,5-DIN] = 1.25 × 10− 5 M, T = 20 ºC, V0 = 3000 µL, λex = 317 nm).

As it is seen in Fig. 6A, the dosage of p-xylene into the benzene solution of DIN exhibits a significant concentration dependent drop of the original double peak structure at 338 and 348 nm, respectively. At the same time, the emission intensity increases at the lower energy (higher wavelength) > 380 nm region of the spectrum. The presence of one distinct isosbestic point at 369 nm indicates the presence of two chemical species, which are assumed to be the benzene and p-xylene being in complex with 1,5-DIN. Similar effects can be observed in the case of toluene-p-xylene system, where the isosbestic point is found at 375 nm. In contrast to that, when toluene was added to the benzene solution of 1,5-DIN, only the decrease of the peaks is evident. The reversed changes at lower and higher wavelengths may provide a facile ratiometric analytical method for the detection (determination) of p-xylene. The unambiguous detection of toluene may not be realized because of the lack of a selective bands. The development of a precise analytical method goes beyond the scope of this paper, it can be concluded, however that the detection limit of p-xylene in benzene is well below 0.027 M or 0.33% (v/v) as is demonstrated in Fig. 6A.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of 1,5-diisocyanonaphthalene

The synthesis and detailed optical study of 1,5-Diisocyanonaphthalene (DIN) is detailed in Ref.30. The aromatic solvents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and were used as received. However, fluorescence spectra were recorded of each pure solvent to check their purity.

UV–vis

The UV–vis spectra were recorded on a UV-6300PC double beam spectrophotometer (VWR International) in a quartz cuvette of 1.00 cm optical length. A 3.00 cm3 solution was prepared from the sample. Background was recorded for the pure solvent in the reference cuvette.

Fluorescence measurements

Steady-state fluorescence measurements were carried out using a Jasco FP-8550 fluorescence spectrophotometer equipped with a Xe lamp light source. The excitation and emission spectra were recorded at 20 °C, using 2.5 nm excitation, 2.5 nm emission bandwidth and 200 nm/min scanning speed. Fluorescence quantum yields (ΦF) were calculated by using quinine-sulfate as the reference, using the following equation:

where Φr is the quantum yield of the reference compound (quinine-sulfate in 0.1 mol/L perchloric acid32, absolute quantum efficiency (Φr = 60%)), n is the refractive index of the solvent, I is the integrated fluorescence intensity and A is the absorbance at the excitation wavelength. The absorbances at the wavelength of excitation were kept below A = 0.1 in order to avoid inner filter effects.

For UV–vis and fluorescence measurements, the investigated compounds were dissolved in acetonitrile at a concentration of 3.76 mM and were diluted to 1.25 × 10− 5 M (for FL) and 1.25 × 10− 5 M, 2.49 × 10− 5 M, 3.72 × 10− 5 M, 4.95 × 10− 5 M and 6.16 × 10− 5 M (for UV-Vis) in the solvents in interest. The molar extinction coefficients were calculated using the Lambert-Beer Eq.

and taking the average of the five measurements:

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations

To obtain an explanation for the spectral changes which takes into account the electronic structure of the species, a previously tested calculation protocol was adopted. All computations were carried out with the Gaussian16 program package (G16C1)33, using standard convergence criteria for the gradients of the root mean square (RMS) Force, Maximum Force, RMS displacement and maximum displacement vectors (3.0 × 10–4, 4.5 × 10–4, 1.2 × 10–3 and 1.8 × 10–3). Optimization and vibrational frequencies were carried out by the M06-2X method34 using the 6-311 + + G(2d,2p) basis set35 and the IEFF-PCM method36 (ε = 78.3553 for acetonitril). The optimized geometry was confirmed as a true minimum on the potential energy surface by the absence of imaginary frequencies in a vibrational frequency analysis performed at the same level of theory. Thermodynamic functions were computed at 298.15 K. For wavelength prediction, the vertical excitation was modelled by the TD-M06-2X/6-311 + + G(2d,2p)[PCM(MeCN)] level of theory [S1(LE)] using the optimized ground state geometries considering 6 states, which proved to be enough. The emission wavelengths were calculated after optimization using geometries provided by TD-M06-2X/6-311 + + G(2d,2p)[PCM(MeCN)], considering 6 states.

We conducted a limited benchmark study to justify the selection of the method and basis set, as shown in Table S6-7. The study included HF, B3LYP, B3LYP-GD3, M06, M06-2X, and WB97XD methods paired with the 6-31G(d), 6-31G(d, p), 6–31 + + G(d, p), 6-311 + + G(2d,2p), aug-ccVDZ, and aug-ccVTZ basis sets. Among these, the M06-2X, B3LYP-GD3, M06 and WB97XD methods combined with a classical basis set provided correct π-π complex geometry and reliable enthalpy values for the sandwich structure. Interestingly, the aug-ccVDZ and aug-ccVTZ basis sets resulted in geometries that were physically incorrect, with the two rings positioned unrealistically far apart (> 5 Å). Furthermore, certain methods, such as HF and B3LYP, produced low and unrealistic enthalpy values and unorganized geometry, which does not represent the sandwich structure. Given that dispersion corrections to B3LYP had significant impact toward the correct geometry.

After careful consideration, we selected the M06-2X/6-311 + + G(2d,2p) level of theory as it offered the best balance between accuracy and computational reliability for our system. The M06-2X method had previously proven effective in modelling molecular complexes in earlier studies. The high-level basis set, 6-311 + + G(2d,2p), was chosen to meet the stringent requirements of TD and triplet state calculations, to obtain accurate and correct excitation and emission wavelengths calculated.

Conclusions

This paper explores the fluorescent properties of 1,5-diisocyanonaphthalene (1,5-DIN) in the presence of different aromatic solvents and highlights its potential for the differentiation of aromatics based on the shape and position of the emission spectrum. While UV-Vis spectra were consistent across solvents, the emission spectra varied significantly, exhibiting solvent-specific redshifts. Benzene retained a double peak, toluene exhibited a broader peak, and p-xylene displayed a pronounced charge transfer-like band at 380 nm. These shifts were attributed to π-π interactions, supported by DFT calculations, which revealed strong binding in m-/p-xylenes and weaker interactions in benzene and pyridine. Comparative studies with 1,5-diaminonaphthalene (DAN) and 1-isocyano-5-aminonaphthalene (ICAN) revealed that aromatic interactions correlate with the electron density of the naphthalene core, with lower electron density favoring π-complex formation. The redshifts correlated with the electron-donating ability of the solvents, with electron-donating groups enhancing π-complex formation, while electron-withdrawing groups showed minimal interaction. Key findings included emission redshifts of 10–30 nm, solvent-specific complexation enthalpies, and significant charge transfer in the presence of electron-donating groups. This work demonstrates the potential of 1,5-DIN as a fluorescence-based tool for differentiating aromatic solvents and analyzing industrially important benzene-toluene-xylene (BTX) mixtures. A detection limit for p-xylene in benzene below 0.027 M (0.33% v/v) highlights its sensitivity and utility for compositional analysis.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, D. & Wang, H. Cation – π interactions between Flame Chemi-ions and aromatic compounds. Energy Fuels 31, 2345–2352. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.6b02354 (2016).

Martinez, C. R. & Iverson, B. L. Rethinking the term pi-stacking. Chem. Sci. 3. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2sc20045g (2012).

Yang, S. Y., Qu, Y. K., Liao, L. S., Jiang, Z. Q. & Lee, S. T. Research Progress of Intramolecular π-Stacked small molecules for device applications. Adv. Mater. 34. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202104125 (2021).

Liu, C. H., Niazi, M. R. & Perepichka, D. F. Strong enhancement of π-Electron Donor/Acceptor ability by complementary DD/AA Hydrogen Bonding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 17312–17321. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201910288 (2019).

Roche, G. H. et al. π-Conjugated organosilica semiconductors: Toward robust organic electronics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 3. https://doi.org/10.1002/aelm.201700218 (2017).

Wei, W. et al. Modulation of π-linkers in asymmetric thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules enabling high performance OLEDs. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 3663–3668. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9tc06608j (2020).

Liu, S. et al. Efficiency enhancement of organic photovoltaics by introducing high-mobility curved small-molecule semiconductors as additives. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 12740–12750. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9ta02636c (2019).

Hundal, A. K. et al. Enhanced photovoltaic efficiency via control of self-assembly in cyanopyridone-based Oligothiophene Donors. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 919–924. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c03526 (2021).

Zhang, J., Xu, W., Sheng, P., Zhao, G. & Zhu, D. Organic donor–acceptor complexes as novel organic semiconductors. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 1654–1662. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00124 (2017).

Keiluweit, M. & Kleber, M. Molecular-level interactions in soils and sediments: the role of aromatic π-Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 3421–3429. https://doi.org/10.1021/es8033044 (2009).

Wijnja, H., Pignatello, J. J. & Malekani, K. Formation of π–π complexes between Phenanthrene and Model π-Acceptor Humic subunits. J. Environ. Qual. 33, 265–275. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2004.2650 (2004).

Sasidharan, S. & Ramakrishnan, V. In Protein Design and Structure Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology 119–160 (2022).

Parker, M. P. et al. Mutual complexation between π–π stacked Molecular tweezers. Cryst. Growth Des. 18, 386–392. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.7b01376 (2017).

Aguiló, E. et al. Reversible self-assembly of Water-Soluble Gold(I) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 57, 1017–1028. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02343 (2017).

Yoshida, M., Hirao, T. & Haino, T. Self-assembly of neutral platinum complexes controlled by thermal inputs. Chem. Commun. 58, 8356–8359. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2cc02571j (2022).

Lehn, J. M. Supramolecular Chemistry: Concepts and Perspectives (Wiley, 2011).

Hunter, C. A. & Sanders, J. K. M. The nature of.pi.-.Pi. Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 5525–5534. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00170a016 (2002).

Chen, Z., Lohr, A., Saha-Moller, C. R. & Wurthner, F. Self-assembled pi-stacks of functional dyes in solution: structural and thermodynamic features. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 564–584. https://doi.org/10.1039/b809359h (2009).

Claessens, C. G. & Stoddart, J. F. π-π interactions in self-assembly. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 10, 254–272 (1997).

Thakuria, R., Nath, N. K. & Saha, B. K. The nature and applications of π–π interactions: a perspective. Cryst. Growth Des. 19, 523–528. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.8b01630 (2019).

Živković, J. M., Stanković, I. M., Ninković, D. B. & Zarić, S. D. Decisive Influence of Environment on Aromatic/Aromatic Interaction Geometries. Comparison of Aromatic/Aromatic Interactions in Crystal Structures of Small Molecules and in protein structures. Cryst. Growth. Des. 21, 1898–1904. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.0c01514 (2021).

Tewari, A. K., Srivastava, P., Singh, V. P., Singh, P. & Khanna, R. S. Molecular recognition phenomenon in aromatic compounds. Res. Chem. Intermediat. 39, 2925–2944. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11164-012-0849-6 (2013).

Headen, T. F. et al. Structure of pi-pi interactions in aromatic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5735–5742. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja909084e (2010).

Verma, K. Detection of aromatic nitro compounds by means of their π-complexes with N,N-diethylaniline. Talanta 28, 485–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-9140(81)80074-4 (1981).

Kovács, E. et al. Synthesis and supramolecular assembly of fluorinated biogenic amine recognition host polymers. Polym. Chem. 10, 5626–5634. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9py00929a (2019).

Levine, M. Fluorescence-based sensing of Pesticides using Supramolecular Chemistry. Front. Chem. 9, 616815. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2021.616815 (2021).

Nagy, M. et al. Solvatochromic study of highly fluorescent Alkylated isocyanonaphthalenes, their π-Stacking, Hydrogen‐Bonding Complexation, and quenching with pyridine. ChemPhysChem 15, 3614–3625. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.201402310 (2014).

Nagy, M. et al. Antifungal activity of an original amino-isocyanonaphthalene (ICAN) compound family: promising broad spectrum antifungals. Molecules 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25040903 (2020).

Szigeti, Z. M. et al. Potential original drug for Aspergillosis: In vitro and in vivo effects of 1-N,N-dimethylamino-5-isocyanonaphthalene (DIMICAN) on Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Fungi 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof8100985 (2022).

Kopcsik, E. et al. Preparation and optical study of 1-formamido-5-isocyanonaphthalene, the hydrolysis product of the potent antifungal 1,5-diisocyanonaphthalene. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24097780 (2023).

Xiong, Z. et al. Reexamining the heavy-atom-effect: the universal heavy-atom-induced fluorescence enhancement principle for through-space conjugated AIEgens. Chem. Eng. J. 451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.139030 (2023).

Nawara, K. & Waluk, J. Goodbye to quinine in sulfuric acid solutions as a fluorescence quantum yield standard. Anal. Chem. 91, 5389–5394. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.9b00583 (2019).

Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01 (Wallingford, CT, 2016).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x (2007).

Krishnan, R., Binkley, J. S., Seeger, R. & Pople, J. A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 72, 650–654. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.438955 (1980).

Tomasi, J., Mennucci, B. & Cammi, R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 105, 2999–3094. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr9904009 (2005).

Funding

The project was supported by TKP2021-NVA-14 grant of the National Office of Science, Innovation and Technology (NKFIH), János Bolyai Research Scholarship and National Excellence Program (BO/799/21/7, ÚNKP-22-ME3). The authors are grateful for the possibility to use ELKH Cloud. Erika Kopcsik is grateful for the support of the New Hungarian National Excellence Program (ÚNKP-23-3-I-ME/15).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M. N., Z.M. and E.K.; methodology, M.N., E. K. and R.S.; software, M. N. and B. V.; formal analysis, E.K. and R.S.; resources, M. N. B. V.; data curation, E.K. and M. N; writing—original draft preparation M.N. and Z.M.; writing—review and editing, M. N., Z.M. and L. V.; visualization, M.N. Z.M. and E.K.; supervision, M.N., Z.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A patent application under the number of P2400531 has been filed by the authors at the University of Miskolc.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kopcsik, E., Mucsi, Z., Schiwert, R. et al. Aromatic pi-complexation of 1,5-diisocyanonaphthalene with benzene derivatives. Sci Rep 15, 629 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84769-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84769-3