Abstract

This study presents an integrated framework that combines spatial clustering techniques and multi-source geospatial data to comprehensively assess and understand geological hazards in Hunan Province, China. The research integrates self-organizing map (SOM) and geo-self-organizing map (Geo-SOM) to explore the relationships between environmental factors and the occurrence of various geological hazards, including landslides, slope failures, collapses, ground subsidence, and debris flows. The key findings reveal that annual average precipitation (Pre), profile curvature (Pro_cur), and slope (Slo) are the primary factors influencing the composite geological hazard index (GI) across the province. Importantly, the relationships between these key factors and GI exhibit spatial variability, as evidenced by the random intercept and slope models, highlighting the need for customized mitigation strategies. Additionally, the study demonstrates that land use patterns and stratigraphic stratum lithology significantly impact the cluster-specific relationships between the key factors and GI, emphasizing the importance of natural resource management for effective geological hazard mitigation. The proposed integrated framework provides valuable insights for policymakers and resource managers to develop spatially-aware strategies for geological hazard risk reduction and climate change adaptation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Geological hazards, including landslides, slope failures, collapses, ground subsidence, and debris flows, present significant challenges to human society, economic development, geographic environments, and ecosystems1, undermining biodiversity and social sustainability2. These hazards arise from complex interactions between Earth’s internal and external processes and have become increasingly frequent and severe due to global climate change and rapid urbanization3,4. Therefore, understanding the underlying mechanisms5,6 driving these hazards and developing effective risk assessment7,8 and management strategies are crucial for mitigating their impacts.

Traditional research on geological hazards has largely relied on statistical modeling and spatial analysis9,10. Statistical models, such as regression analysis, have been instrumental in identifying key environmental factors contributing to hazard occurrences11, providing a foundational understanding of these processes. Similarly, spatial analysis methods, particularly those utilizing geographic information systems (GIS), have been pivotal in mapping hazard-prone areas12,13,14. However, these approaches often assume linear relationships between variables, which may oversimplify the inherent complexity and nonlinear nature of geological processes, leading to potential inaccuracies in hazard assessments. Such limitations necessitate the exploration of more sophisticated modeling techniques that can better accommodate the complexities involved.

In recent years, machine learning and deep learning techniques have emerged as powerful tools in geological hazard research15,16, providing significant advancements over traditional methods. These methods, including support vector machines (SVM), random forests (RF), and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), excel in handling large datasets and modeling complex, nonlinear relationships between variables. For instance, SVMs have been effectively applied to classify geological hazard zones by analyzing key environmental factors17,18, thereby enhancing prediction accuracy by accommodating nonlinear decision boundaries. RFs, on the other hand, have been employed to identify critical predictors of landslide susceptibility19,20, offering robust handling of large and imbalanced datasets while capturing complex variable interactions. Furthermore, CNNs have been utilized to analyze satellite imagery for detecting and mapping landslides with high spatial resolution21,22, thus providing precise spatial data interpretations. Despite these advantages, many of these models often overlook spatial dependencies by treating data points as independent observations, which neglects the geographic context essential for understanding hazard variations.

A significant limitation of existing research is its tendency to focus on individual hazards in isolation, failing to consider the interrelated nature of geological hazards. Many studies concentrate solely on single hazards, such as landslides1 or debris flows23, without accounting for the interactions between different types of hazards. This narrow focus fails to capture the complex risk landscape created by multiple, interacting hazards, such as heavy rainfall triggering landslides, debris flows, and floods simultaneously7,24,25. Ignoring such interactions can lead to incomplete risk assessments and inadequate mitigation strategies.

Moreover, traditional models often fail to incorporate the spatial interdependencies among hazards, which are influenced by geographic and environmental factors that vary significantly across different regions26,27. This oversight can result in inaccurate risk assessments and ineffective management strategies. Therefore, there is a growing recognition of the need for more integrated approaches that consider multiple hazards and their spatial relationships.

To address these gaps, developing comprehensive frameworks that capture both the nonlinear relationships between geological hazards and their environmental, socioeconomic, and anthropogenic drivers is essential. Such frameworks would not only improve hazard prediction accuracy but also enhance our understanding of the complex interactions that drive these events. Advanced clustering algorithms28,29, such as self-organizing map (SOM) and their geographic extension, Geo-SOM, have shown significant promise in this regard. These methods excel at identifying patterns within high-dimensional data, making them particularly effective for analyzing the complex, nonlinear relationships between various geohazard factors and their environmental and socioeconomic drivers30,31.

Hunan Province in central south China, with its diverse topography and high susceptibility to various geological hazards32, presents a unique case study for applying these advanced clustering techniques. The geographic and climatic diversity of Hunan poses significant challenges for hazard assessment and management, making it an ideal region to explore the benefits of SOM and Geo-SOM.

In this study, we address the aforementioned gaps by developing a composite geological hazard index (GI) that reflects the occurrence frequencies of various geological hazards in Hunan Province. We apply SOM and Geo-SOM clustering analyses to investigate the spatial relationships between environmental factors—such as topography, forestry, and stratum lithology—and geological hazard risks across the province’s counties. Additionally, we employ linear mixed models (LMMs) to model the comprehensive hazard response, integrating multi-source geospatial data to enhance the accuracy and interpretability of our findings. The objectives of this study are threefold: (i) to assess the necessity of spatial clustering in understanding the relationships between environmental factors and geological hazards; (ii) to identify major predictive factors associated with geological hazards in each county-level region; and (iii) to explain the response mechanisms of different regional and typological geological hazards to these key environmental factors.

This study aims to contribute to the development of integrated, multi-hazard assessment frameworks that account for spatial interdependencies and nonlinear relationships, providing policymakers with the necessary tools for more effective risk management strategies.

Study area and data

Study area

Hunan province (24° 38′–30° 08′ N, 108° 47′–114° 15′ E), with an area of approximately 211,800 km2 (Fig. 1), is located in the transition zone from the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau to the hilly region of Jiangnan and the Nanling Mountains to the Jianghan Plain. The topography of Hunan province is diverse, characterized by a hot and humid climate with an annual average temperature of 16–18 °C and annual rainfall of 1100–1800 mm. The Luoweng-Suining Fault Zone and the Yong’an Fault Zone divide Hunan into two major tectonic units, significantly affecting the provincial geological structure and geological hazards. As of 2020, the forest coverage rate in Hunan province is approximately 61.1%. The province is well-known for its abundant and widely distributed limestone geological resources.

Data sources and impact factor processing

This study integrates various data sources, including: (i) Geological hazard data, such as landslides, slope instability, collapses, ground subsidence, and debris flows, obtained from the Department of Natural Resources of Hunan Province (https://zrzyt.hn.gov.cn). This dataset includes 8082 geological hazard events across 121 county-level units from 2012 to 2021. (ii) Stratum lithology (SL) data from the GeoCloud Platform (https://geocloud.cgs.gov.cn). (iii) Digital elevation model (DEM) data from the Geospatial Data Cloud Platform (https://www.gscloud.cn), used to generate fundamental geographic environmental factors including elevation (Ele), slope (Slo), aspect (Asp), planar curvature (Pla_cur), profile curvature (Pro_cur), and the terrain wetness index (TWI). (iv) Landsat-8 imagery provided by the United States Geological Survey (https://www.usgs.gov) to extract the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI). (v) Standardized precipitation index (SPI), annual average precipitation (Pre), and distance to fault zones (DFZ) data from the Resource and Environment Science Data Platform (https://www.resdc.cn). (vi) Land use (LU) data from the annual land cover dataset of China published by Wuhan University (https://www.whu.edu.cn). Additionally, population density (PD) and gross domestic product (GDP) data were obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics (https://www.stats.gov.cn).

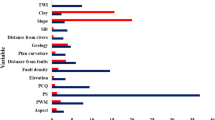

Selecting potential impact factors for geological hazards was guided by extensive research and established best practices in understanding the mechanisms of these hazards16,24. In this study, 14 impact factors were carefully selected from five aspects: topography and geomorphology (Ele, Slo, Asp, Pla_cur, and Pro_cur), geological structure (SL and DFZ), hydrology and ecology (SPI, Pre, TWI, NDVI), human activities (LU, PD, and GDP). Maps of SL and LU are presented in Figs. A.1 and A.2 in Supplementary Appendix A, respectively. Descriptive statistics for other factors are provided in Table A.1 in Supplementary Appendix A.

Further, a multicollinearity analysis was conducted on 12 numeric impact factors. The two categorical factors (SL and LU) were not included in subsequent modeling and were primarily used to discuss their respective impacts on geological hazards under specific cluster conditions. The results of the multicollinearity test, shown in Fig. 2, indicate that factors with a VIF greater than 10 (i.e., Asp, SPI, and TWI) were excluded, leaving 9 numeric factors to form the impact factor dataset for subsequent modeling.

Methodology

The proposed methodology is illustrated in Fig. 3. Drawing inspiration from the Nemerow index33, a composite geological hazard index (GI) was developed to evaluate risks from landslides, slopes, collapses, ground subsidence, and debris flows across counties. After conducting multicollinearity analysis among numerical variables, the relationships with the GI were evaluated using SOM and Geo-SOM. To explore the spatial variability, the clustering results were incorporated as random effects in the LMMs, with numerical variables were used to explain the GI. By comparing pre-selected numerical variables from SOM and Geo-SOM with those in LMMs, main triggering factors were identified and their relationship with the GI was evaluated.

The composite geological hazard index (GI)

The concept of the Nemerow index, traditionally used in the fields of water resource management and environmental monitoring, is adapted here for evaluating geological hazards. This study focuses on the frequency of landslides, slope failures, collapses, ground subsidence, and debris flows. The construction of the composite geological hazard index (GI) involves three main steps:

Initially, the background value B is established, serving as a reference point for the evaluation of geological hazard risk in each county. This is accomplished by considering the mean frequency of various geological hazards across all counties within Hunan province. Subsequently, the single factor index for each county is computed. This involves the determination of the single factor index for the various geological hazards based on Eq. (1):

where Fi represents the frequency of the ith type of hazard, and Bi is the background value of the ith hazard, which can quantify the geological hazard risk of each county relative to the background situation. Finally, the composite geological disaster index (GI) is computed utilizing Eq. (2):

where \(\overline{{G_{i} }}\) is the average value of the single factor index for all types of geological hazards, and Gimax is the maximum value of the single factor index of all types of geological hazards.

Self-organizing map (SOM) and geo-self-organizing map (Geo-SOM)

The Self-Organizing Map (SOM) is an unsupervised neural network technique that clusters high-dimensional data while preserving topological relationships between variables, revealing patterns that are not immediately apparent in raw data34. A SOM network consists of a topologically ordered grid composed of one or more neurons, typically in two dimensions. During the training process, each input data sample competes with the output layer neurons, with the most similar neuron being activated. Subsequently, the weights of the activated neuron and its neighboring neurons are updated to better fit the input data, resulting in similar input data points being mapped to adjacent neurons. SOM neural networks have been extensively applied in cluster analysis of geohazard impact factors29, by inputting multidimensional data of various geohazard events into the SOM network to generate a SOM cluster map, where each neuron represents a group of similar geohazard impact factors. This process aids in identifying potential correlations and patterns between factors, facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of the driving mechanisms of geohazards and a better comprehension of the complexity of geohazards.

Geographical Self-Organizing Map (Geo-SOM), an extension of SOM, further enhances this capability by incorporating geographic constraints, ensuring that spatially adjacent data points are mapped together35. Geo-SOM integrates the core concept of SOM, i.e., mapping multidimensional data onto a low-dimensional topological space, with the functionality of Geographic Information Systems, to better understand the spatial distribution and relationships of geographical data. Unlike traditional SOM, Geo-SOM emphasizes the continuity of geographical space, ensuring that geographically adjacent objects are also approximately mapped together in the SOM. Geo-SOM is a potent tool for analyzing and visualizing geographical data, combining the principles of unsupervised learning in SOM and the functionality of geographic information systems (GIS). It has been widely used in research on geological hazards, especially in the study of landslide susceptibility mapping36.

The dataset entered into the SOM or Geo-SOM consists of 121 county-level unit samples, each containing 9 attribute values corresponding to 9 numerical variables. In order to meet the conditions of normality and homoscedasticity of residuals, log transformation was performed on variables with a wide range. All factors were then readjusted to the range of [0,1]. To achieve the best data pattern expression and visualization effects37, after multiple experiments and comparisons, the output map size was set to a 7 × 8 grid. In order to adapt to the complexity of the dataset and avoid overfitting or underfitting, after repeated experiments and verification, the iteration times of coarse training and fine training of SOM were set to 500 and 1000, respectively, while those of Geo-SOM were both set to 1500. The learning rates of the two algorithms in the two training stages were set to 0.4 and 0.2, respectively. Moreover, evaluating the performance of Geo-SOM depends on assessing geographical error, a factor closely related to the geographical tolerance parameter, denoted as ‘k’31. After comprehensively analyzing error responses and clustering results across a range of values from 0 to 15, the most suitable value for this tolerance parameter was determined to be 6.

In order to evaluate the relationships between geological hazards and impact factors from the training results of SOM and Geo-SOM, the composite index of geological hazards, GI, was used as an auxiliary variable, which means it does not directly affect the clustering or sorting results based on numerical environmental variables (deterministic variables). The composite index of geological hazards, GI, was inputted into the SOM and Geo-SOM neural networks trained by environmental variables, and the average value of GI in each neuron of the trained map was calculated. When an output neuron is not occupied by an input vector, the average value of adjacent neurons is used to calculate this value30. The distribution of the composite index of geological hazards, GI, on the component plane can provide detailed information about the influence of environmental factors on the distribution of Gi. To determine the correlation between each environmental variable and GI, the weight values of each node from each component plane defined by the training of SOM and Geo-SOM were extracted, which were used for the component planes of auxiliary variables and deterministic variables. The similarity of data patterns was evaluated by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient, and impact factors with a high correlation with GI were screened out for comparison with the results of other LMMs. Based on the maps obtained from SOM and Geo-SOM training, k-means clustering was also performed to identify data clusters with inherent correlation. The appropriate number of clusters was obtained according to the Davies–Bouldin index38 to better understand the relationship between the composite index of geological hazards and different impact factors. This method is expected to provide more in-depth and comprehensive insights to better understand the correlation between the distribution of the composite index of geological hazards and impact factors.

Linear mixed model (LMM)

To assess the importance of considering spatial clustering when elucidating the relationships between geological hazards and impact factors, the LMMs with a grouping factor were employed. The grouping factors, derived from SOM and Geo-SOM analyses, were treated as random effects in the LMMs. An LMM is a statistical model that includes both fixed and random effects to analyze data with dependencies, such as hierarchical or repeated measures data. To enhance interpretation and simplify the analysis process, separate LMM analyses were conducted for the geological hazard index (GI) in this study. The analysis process was as follows:

-

(i)

To assess the appropriateness of classification, cluster results from SOM or Geo-SOM were incorporated as random effects in LMMs to elucidate relationships between the GI index and 9 impact factors. Model selection was carried out using the “dredge” function to identify the “best models” based on a criterion of ΔAICc < 2 by considering possible combinations of fixed effects. The LMMs incorporating clustering results were compared with a generalized least-square (GLS) regression model that solely accounted for fixed effects. Model selection among the GLS, LMM with SOM clustering, and LMM with Geo-SOM clustering was based on a comparison of Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) values.

-

(ii)

To identify the primary triggering factors associated with the GI index, the analysis involved comparing coefficients and the significance of a selected combination of “best models”. These models were considered in relation to 9 impact factors that demonstrated a consistent directional relationship (either negative or positive) and exhibited a strong correlation with the GI index on the SOM or Geo-SOM component planes. For the LMM results, contributions of each factor were estimated by aggregating the Akaike weights (AICc-w) from the models identified as the “best models”. Coefficients were determined through a model averaging approach.

-

(iii)

To analyze the variability in the relationships between impact factors and the GI index within different clusters, LMMs were used to predict the GI index using a single triggering factor, along with a random intercept. Additionally, random intercepts and slopes were incorporated based on the grouping structure to explore how the relationships between impact factors and the GI index varied across different clusters. To assess model performance, a comparison was made with GLS models sharing the same structure but lacking the random effects introduced by the clustering. To elaborate on the variations in the triggering and response relationships for secondary factors (2 categorical variables—stratum lithology and land use type), a generalized least squares (GLS) regression analysis of the general effects of their patterns on cluster-specific intercepts was conducted. All analyses, including LMMs and GLS regression, were carried out using the statistical software R version 3.5.0 (https://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Clustering by SOM and Geo-SOM

As shown in Fig. 4, the Geo-SOM clusters, which account for geographical location, exhibited distinct spatial patterns, while SOM resulted in a more irregular distribution of clusters. Both SOM and Geo-SOM identified 5 clusters, each characterized by different geological hazard risk levels and impact factors (Table 1).

Table 1 shows the impact factors and composite geological hazard indices of the five SOM-generated clusters, with Cluster 1 having the highest average geological hazard risk (GI = 3.812), followed by Cluster 3 (GI = 2.261). Observations grouped into Clusters 1 and 3 had high average values for non-human activity factors such as elevation (604.832 and 203.146 m), slope (7.3 and 2.838°), NDVI (0.836 and 0.778) and annual average precipitation (1436.501 and 1514.281 mm); and low average values for human activity factors including population density (463.408 and 542.250 people/km2) and GDP (113.175 and 273.004 billion yuan). In contrast, Cluster 5 had the lowest geological hazard risk (GI = 0.439) with the lowest mean values for non-human activity factors such as elevation (63.006 m), slope (0.794°) and NDVI (0.640); and the highest mean values for human activity factors including population density (3215.357 people/km2) and GDP (1389.507 billion yuan). Due to the lack of geographical location considerations, the SOM training results did not exhibit spatial patterns in the factors and hazard indices.

The 5 clusters identified by Geo-SOM were spatially distinct and characterized by the impact factors and composite geological hazard indices (Table 2). Cluster 2, consisting of 14 southeastern counties, had the highest GI (3.185). In contrast, Cluster 5, with 17 central and northern counties, had the lowest GI (0.690). Observations in Cluster 2 had the highest average values for non-human activity factors such as elevation (590.856 m), slope (6.552°) and annual average precipitation (1502.651 mm); and low values for human activity factors (PD = 419.849 people/km2; GDP = 135.968 billion yuan). Conversely, Cluster 5 had relatively low non-human activity factors (e.g., elevation 52.457 m; slope 0.655°; NDVI 0.735; annual average precipitation 1363.291 mm) and relatively high human activity factors (PD 801.961 people/km2; GDP 267.357 billion yuan). Geo-SOM clustering outcomes exhibited significant spatial characteristics.

The training results of SOM and Geo-SOM showed similarities in the correlation between impact factors and the composite index of geological hazards GI (Fig. 5, Table A.2 in Supplementary Appendix A). From the weight results of the SOM training and Geo-SOM training in the component planes, it can be observed that they both had 5 identical variables highly correlated with GI (P < 0.05). However, the order of correlation for those variables differed between the two algorithms. For SOM, the descending order was as follows: Pro_cur (R = 0.726), Pla_cur (R = 0.703), Ele (R = 0.668), Pre (R = 0.642) and Slo (R = 0.466). For Geo-SOM, the descending order was as follows: Pre (R = 0.753), Pla_cur (R = 0.739), Pro_cur (R = 0.714), Slo (R = 0.623) and Ele (R = 0.484). The two socio-economic variables, namely PD and GDP, showed low negative correlations with GI in both the SOM (R = − 0.263 and R = − 0.281) and Geo-SOM (R = − 0.221 and R = − 0.260) algorithms.

Screening of clustering and impact factors

The LMM model incorporating the random effect of Geo-SOM clustering exhibited superior predictive performance for the composite index of geological hazards (GI) across all 9 impact factors. In other words, this model outperformed both the GLS model and the LMM model with the random effect of SOM clustering. Table 3 provides a summary of these findings. Additionally, the random effect of Geo-SOM clustering was found to provide the best explanation for the GI index. To determine the variables most strongly correlated with the GI index, the variables selected by the LMMs with random effects of Geo-SOM clustering were compared to those identified through the weight of the Geo-SOM training.

The factor importance for the GI index was determined by averaging the results from a selection of the best models out of the 512 possible combinations. The coefficients and contributions of factors in the averaged linear mixed models (LMMs), which included the random effect of clustering trained by Geo-SOM, were assessed based on a threshold of ΔAICc < 2 from the total of 512 models. Using this criterion, the average coefficients for all 9 factors were calculated, with the descending order being Pre, Pro_cur, Pla_cur, Slo, Ele, NDVI, GDP, PD, and DFZ. The corresponding coefficients were found to be 17.582, 9.034, − 5.565, 2.932, − 1.130, 0.487, − 0.381, − 0.124, and − 0.007, respectively. From the coefficients of factors, Pre, Pro_cur, Pla_cur, Slo, Ele contributed the most to the description of GI in the averaged model. These factors had a contribution value of 1.00 in the best-fit models, indicating their strong influence on the GI.

After comparing the node weights obtained from the Geo-SOM training, it was determined that the factors Pre, Pro_cur and Slo were identified as key impact factors for GI. These factors made high contributions to the description of GI. However, in contrast, Pla_cur and Ele variables were considered less important factors. This classification was based on the discrepancies in the signs of their coefficients between the Geo-SOM (0.739 and 0.484) and LMM (− 5.565 and − 1.130) analyses. These inconsistencies in sign indicate that the relationship between GI, Pla_cur, and Ele is not stable or reliable. Hence, their significance in assessing GI is questionable.

The relationships between screened variables and GI index

The random intercept and slope models and the random intercept models both showed significantly better performance in explaining GI using the key impact factors compared to the GLS models. Regarding the relationships between Pre and GI, as well as Pro_cur and GI, the random intercept and slope models generally outperformed the random intercept models. For the relationship between Slo and GI, the random intercept models typically performed better than the random intercept and slope models (Table A.3 in Supplementary Appendix A). Specifically, cluster 2 and 3 demonstrated higher intercept values than the fixed values for the factors Pre and Pro_cur, with varying slopes according to the Geo-SOM clusters. On the other hand, for the factor Slo, cluster 2, 3, and 4 had higher intercept values and relatively fixed slopes based on the Geo-SOM clusters (Fig. 6).

Further research revealed that both land use patterns and stratigraphic stratum lithology had a significant impact on the variation in triggering the composite index GI links. Specially, the percentage of forest and the percentage of limestone were found to have a significantly positive impact on the intercepts of the GI index. The variation in the intercepts, explained by the factors Pre (R2 = 0.61), Pro_cur (R2 = 0.76) and Slo (R2 = 0.58) was significantly influenced by the percentage of forest area (p < 0.05). Similarly, the variation in the intercepts, explained by the factors Pre (R2 = 0.43), Pro_cur (R2 = 0.80) and Slo (R2 = 0.85) was significantly influenced by the percentage of limestone area (p < 0.05) (Fig. 7).

Regression lines for the Geo-SOM cluster-specific intercepts with land-use and stratigraphic stratum lithology factors. Relationships of (a) intercepts from the GI ~ Pre model, (b) intercepts from the GI ~ Pro_cur model and (c) intercepts from the GI ~ Slo model with mean proportion of forest area. Relationships of (d) intercepts from the GI ~ Pre model, (e) intercepts from the GI ~ Pro_cur model and (f) intercepts from the GI ~ Slo model with mean proportion of limestone area. Colors of the point and error bars represent the Geo-SOM clusters (see Fig. 6) and the gray line is the regression line.

Discussion

Importance of spatial context

Incorporating Geo-SOM training significantly enhanced the explanatory power of the LMMs, surpassing models utilizing SOM clustering (Table 3). This demonstrates the critical role of Geo-SOM clustering in capturing the spatial dependencies between impact factors and the composite index of geological hazards (GI) in Hunan province. This finding aligns with previous studies emphasizing the importance of considering spatial dependency when evaluating the impacts of impact factors on geological hazards1,39.

The distinct spatial clusters identified by the Geo-SOM analysis provide valuable insights into the regional heterogeneity of geological hazard occurrences. For instance, Cluster 2, comprising 14 southeastern counties, exhibited the highest composite geological hazard index (GI = 3.185). This cluster was characterized by high mean values for non-human activity factors, such as elevation, slope, and annual average precipitation, as well as relatively low human activity factors, including population density and GDP. In contrast, Cluster 5, consisting of 17 central and northern counties, had the lowest GI (0.439) and was associated with lower non-human activity factors and higher human activity factors. These spatial variations underscore the importance of accounting for geographic context when assessing the complex interplay between environmental conditions and geological hazard risks26. This approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of the factors contributing to geological hazards and can inform targeted mitigation strategies.

Variation in relationships between impact factors and the GI

The factors that have the most significant impact on determining the GI index, as indicated by both Geo-SOM and LMM analyses, were Pre, Pro_cur and Slo. This finding underlines the complexity and multi-dimensionality of geological hazards, which are significantly influenced by both climatic and topographical factors. This finding is consistent with previous studies highlighting the pivotal role of climatic and topographical factors in influencing geological hazards4,7,8.

The strong correlation between precipitation (Pre) and the GI index is consistent with findings from previous studies that have identified rainfall as a primary driver for various geological hazards, including landslides, soil erosion, and flooding23,24. In Hunan province, where the dominant hazards are landslides and collapses, the influence of extreme rainfall events is particularly evident40. The positive correlation between Pre and GI suggests that increased precipitation associated with climate change may heighten the vulnerability of the region to geological hazards.

The impact of profile curvature (Pro_cur) and slope (Slo) on the GI index reflects the role of topography in modulating geological hazards7,8. Profile curvature, which influences the acceleration or deceleration of surface water, can affect the likelihood of surface runoff and erosion. Areas with high profile curvature may be at elevated risk of landslides and soil erosion18. Similarly, steeper slopes increase gravitational forces, thereby increasing the probability of landslides and rockfalls7. The consistent positive relationship between Slo and GI across the Geo-SOM clusters underscores the fundamental importance of slope in determining geological hazard susceptibility.

Response of clusters to key factors

The random effect structure required for explaining the GI index by precipitation (Pre) and profile curvature (Pro_cur) necessitated both random intercepts and slopes to accurately capture the variations among different clusters (Table A.3, Fig. 6). This indicates that the relationships between these factors and the GI index are not uniform across the county-level units, but rather exhibit cluster-specific sensitivities. In particular, the increasing correlation of Pre ~ GI and Pro_cur ~ GI in Cluster 2 (Fig. 6) suggests that areas with more complex terrain (higher Pro_cur) and greater precipitation are more susceptible to geological hazards. This finding further validates the importance of spatial context in evaluating the impacts of environmental factors on geological hazards, as emphasized in Sect. 4.1.

However, the optimal random effect structure for GI as explained by slope (Slo) only included the intercept (Model 8), which had smaller AIC, BIC, and σ, and a larger log-likelihood (Table A.3 in the Supplementary Appendix A). This demonstrates that the relationship between slope and GI remains consistent, irrespective of the underlying conditions related to geological hazards. The random intercept for the Geo-SOM clusters can be interpreted as a measure of the carrying capacity or a baseline score for the counties within each cluster. It depicts the expected score of GI when a county experiences a minimal level of slope, devoid of any other influences. This suggests that counties with scores below the average intercept (0.435) cannot maintain a favorable status of GI, indicating heightened vulnerability to geological hazards.

Impact of land-use and stratigraphic stratum lithology on the GI under cluster-specific conditions

Land-use patterns and stratigraphic stratum lithology significantly influence the variation in cluster-specific conditions. A higher percentage of forest and limestone areas exhibit positive associations with this variation (Fig. 7).

The three LMMs reveal the significance of the proportion of forest area with respect to the GI (Fig. 7a–c). Increasing forest area proportion enhances the precipitation’s impact on the GI (Fig. 7a), likely due to higher precipitation surpassing the forest’s absorption and storage capacity, leading to increased runoff and soil erosion. For instance, cluster 3 shows the highest sensitivity with notable variation in intercept values under increasing forest cover. A higher proportion of forest area may also amplify the curvature’s effect on GI (Fig. 7b), suggesting that forest distribution affects terrain convexity or concavity, indirectly influencing GI. Clusters 2 and 4 reflect substantial increases in intercept values as the forest area rises. Additionally, forest area proportion heightens slope’s impact on GI (Fig. 7c), indicating that forest distribution influences slope inclination, thereby impacting GI. In cluster 1, the intercept values exhibit a marked upward trend with increasing forest coverage.

Similarly, the three LMMs also highlight the significance of the limestone area proportion in relation to the GI (Fig. 7d–f). Increased limestone area enhances precipitation’s impact on GI (Fig. 7d) due to limestone’s lower water absorption and discharge capacity compared to soil, resulting in higher runoff and erosion. Cluster 5 demonstrates the most pronounced intercept variability under this scenario. The limestone area’s influence on profile curvature can heighten GI (Fig. 7e), possibly due to limestone’s geological structure leading to steeper profiles. Clusters 2 and 3 show significant increases in intercept values corresponding with higher limestone proportions. Additionally, the limestone area enhances the slope’s impact on GI (Fig. 7f). The terrain in limestone areas tends to be steeper due to rock hardness and weathering, thus increasing GI. This effect is evident in cluster 4, where intercept values significantly rise with increasing limestone coverage.

In conclusion, both forest and limestone areas significantly impact the relationships between precipitation, profile curvature, slope, and GI. Forest areas amplify these variables’ effects on GI, while limestone areas similarly enhance their impact. These findings suggest that forest and limestone distributions indirectly affect GI by altering water absorption, runoff, erosion, and terrain inclination41,42.

Limitations

Although this study provides valuable insights into the spatial patterns and environmental drivers of geological hazards in Hunan Province, it has several limitations that should be considered. Firstly, the dataset used in this research covers a period of 10 years (2012–2021), which may not fully capture the long-term trends and dynamics of geological hazards in the region. Extending the dataset to a longer time frame could provide more comprehensive insights into the evolving relationships between environmental factors and geological risks. Secondly, while the integration of multi-source geospatial data enabled a more comprehensive assessment, the availability and quality of certain data sources, such as high-resolution land cover information and detailed geological surveys, may limit the accuracy of the analysis. Improving the spatial and temporal resolution of key datasets could further enhance the reliability of the findings. Thirdly, this study focused on the county-level administrative units in Hunan Province. Incorporating smaller geographic units, such as townships or villages, could reveal more localized patterns and vulnerabilities that may be obscured at the county scale. Exploring the scalability of the proposed framework to finer spatial resolutions would be a valuable next step.

Policy recommendations

Based on the findings and discussion presented, it becomes evident that policies aimed at mitigating geological hazards in Hunan Province need to account for the regional heterogeneity highlighted by the distinct clusters. The Geo-SOM analysis and subsequent random effect models reveal that different areas within the province respond uniquely to various environmental and land-use factors. This multifaceted strategy should interweave natural resource management, infrastructure resilience, and socio-economic development initiatives, all embedded within a regulatory framework that can evolve in sync with emerging data and prompt inter-regional cooperation. Below are several policy recommendations based on these insights:

Integrated land and water resource management

The synthesis of precipitation patterns, topography, and land-use in Hunan Province commands an integrated response to manage these interconnected elements. Priority should be given to sustainable forest management, with a concentration on reforestation and afforestation initiatives, especially in regions identified through Geo-SOM clustering as susceptible due to diminished forest cover.

-

(i)

Targeted interventions for slope management in Cluster 1: Cluster 1 exhibits a marked upward trend in intercept values with increasing forest coverage, indicating heightened sensitivity to slope changes. Stabilize high-risk slopes through engineering solutions such as terracing, retaining walls, and vegetation cover to reduce the probability of landslides and rockfalls. Regular slope monitoring and early warning systems could be vital in this area.

-

(ii)

Strategic land use planning in Cluster 2: Cluster 2, characterized by high profile curvature and complex terrain, shows significant increases in GI with higher precipitation and forest coverage. Implement zoning regulations that limit construction and human activities in high-risk areas. Encourage land use that maintains or enhances the natural terrain’s ability to manage water flow, such as wetlands and riparian buffers. Promote soil conservation practices to reduce erosion and sedimentation.

-

(iii)

Enhanced forest management in Cluster 3: Cluster 3 shows notable variation in GI intercepts with increasing forest coverage, indicating high sensitivity to forest area changes. Implement sustainable forest management practices to optimize forest absorption and storage capacity. Introduce reforestation and afforestation programs tailored to the specific precipitation patterns of this cluster to minimize runoff and soil erosion.

-

(iv)

Integrated water resource management in Cluster 4: The terrain in Cluster 4, which is influenced by limestone hardness and weathering, experiences significant GI increases related to slope and precipitation. Develop comprehensive water resource management plans that address both flood prevention and drought resilience. Encourage the construction of permeable surfaces and rainwater harvesting systems to manage stormwater runoff effectively.

-

(v)

Limestone area considerations in Cluster 5: Cluster 5 demonstrates pronounced intercept variability with increased limestone coverage, indicating sensitivity to lower water absorption capacity of limestone. Employ water management strategies that enhance the infiltration and storage capacity of the soil. Use limestone-reinforced soils to reduce runoff and prevent erosion. Develop infrastructure that can withstand rapid changes in hydrology and soil stability.

Customized infrastructure and urban planning with climate adaptation

Improvements in infrastructure design and urban planning are essential, informed by the nuanced insights provided by Geo-SOM cluster analysis. In high-risk areas like the mountainous terrain of Hengyang, infrastructure investments should focus on slope protection, retaining walls, and assessing the robustness of existing structures against geological disturbances. In economically significant areas such as Changsha, urban planning must integrate green spaces and permeable surfaces to reduce surface runoff. For regions with significant elevation variations, such as the Wuling Mountain Range, spatial planning and comprehensive impact assessments of future developments are critical to reducing geological disaster risks.

Climate adaptation strategies should be incorporated across all clusters due to increased precipitation associated with climate change, which amplifies vulnerability to geological hazards. Regional planning regulations must be adaptive, reflecting the latest scientific findings and monitoring data to ensure that building codes enhance safety and resilience. Additionally, educational programs should be established to raise awareness about geological hazards and promote community-based disaster preparedness.

Balancing socio-economic development and environmental protection

To effectively mitigate geological hazards in Hunan Province, policies must harmonize socio-economic growth with environmental sustainability. Achieving this balance involves several strategic approaches:

-

(i)

Economic diversification and sustainable practices: Encouraging industries that both drive economic growth and support environmental management is crucial, particularly in high-risk and underdeveloped areas like parts of Shaoyang. Incentives for sustainable practices should be implemented to avoid increasing disaster risks, ensuring that economic activities are resilient to geological hazards.

-

(ii)

Integrating economic and risk reduction strategies: In regions with significant socio-economic activity, combining economic incentives with risk reduction measures is critical. For example, promoting ecotourism in Zhangjiajie and sustainable agriculture in Yueyang can support economic development while enhancing community resilience to geological risks.

-

(iii)

Managed retreat for extreme risk areas: In communities facing extreme geological hazards, developing relocation and compensation plans is necessary. These plans should help maintain livelihoods while facilitating transitions to safer areas, reducing vulnerability in the long term.

-

(iv)

Region-specific mitigation programs: Tailored mitigation strategies are vital for addressing the unique geological and climatic conditions of different regions within Hunan. This includes implementing customized engineering solutions, land-use policies, and community resilience initiatives that consider local sensitivities and vulnerabilities.

-

(v)

Investment in research and technology: Allocating resources to enhance hazard prediction, early warning systems, and risk management technologies is essential for improving the province’s overall preparedness and response capabilities.

Conclusion

This comprehensive study integrates spatial clustering and multi-source geospatial data to develop an integrated framework for assessing and understanding geological hazards in Hunan Province, China. The key findings are as follows:

-

(i)

The Geo-SOM clustering approach, which incorporates geographical location information, outperformed the traditional SOM clustering in capturing the spatial dependencies between environmental factors and the composite geological hazard index (GI). This highlights the importance of considering spatial context when evaluating the drivers of geological hazards.

-

(ii)

The analysis identified annual average precipitation (Pre), profile curvature (Pro_cur), and slope (Slo) as the primary factors influencing the GI index across Hunan Province. These factors demonstrated strong and consistent correlations with the GI, underscoring the complex interplay between climatic and topographical conditions in shaping geological hazard risks.

-

(iii)

The relationships between the key factors (Pre, Pro_cur, Slo) and GI exhibited spatial variability, as evidenced by the random intercept and slope models. This indicates that the sensitivity of geological hazards to environmental conditions varies across different regions, emphasizing the need for customized mitigation strategies.

-

(iv)

Land use patterns and stratigraphic stratum lithology were found to significantly impact the cluster-specific relationships between the key factors and GI. Increased forest cover and limestone areas amplified the effects of precipitation, profile curvature, and slope on the GI index, suggesting that natural resource management is crucial for geological hazard mitigation.

The findings of this study provide valuable insights for policymakers and resource managers to develop integrated, spatially-aware strategies for geological hazard risk reduction and climate change adaptation in Hunan Province. The proposed framework can serve as a model for other regions facing similar challenges, enhancing our understanding of the complex interplay between environmental factors and geological hazards.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. For requests regarding the data from this study, please contact Weifeng Xiao (472364382@qq.com).

References

Chen, W. et al. Landslide susceptibility modelling using GIS-based machine learning techniques for Chongren County, Jiangxi Province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 626, 1121–1135 (2018).

Luo, S. L., Huang, D., Peng, J. B. & Tomás, R. Influence of permeability on the stability of dual-structure landslide with different deposit-bedding interface morphology: The case of the Three Gorges Reservoir area, China. Eng. Geol. 296, 106480 (2022).

Lin, Q. et al. Evaluation of potential changes in landslide susceptibility and landslide occurrence frequency in China under climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 850, 158049 (2022).

Zhang, H. & Wang, Z. Human activities and natural geographical environment and their interactive effects on sudden geologic hazard: A perspective of macro-scale and spatial statistical analysis. Appl. Geogr. 143, 102711 (2022).

Tracy, A., Javernick-Will, A. & Torres-Machi, C. Human-induced or natural hazard? Factors influencing perceptions of actions to be taken in response to induced seismicity. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 57, 102186 (2021).

Lee, R. et al. Reclassifying historical disasters: From single to multi-hazards. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 169120 (2024).

Lin, J., Chen, W., Qi, X. & Hou, H. Risk assessment and its influencing factors analysis of geological hazards in typical mountain environment. J. Clean. Prod. 309, 127077 (2021).

Zou, F., Che, E. & Long, M. Quantitative assessment of geological hazard risk with different hazard indexes in mountainous areas. J. Clean. Prod. 413, 137467 (2023).

Saha, A. & Saha, S. Application of statistical probabilistic methods in landslide susceptibility assessment in Kurseong and its surrounding area of Darjeeling Himalayan, India: RS-GIS approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 4453–4483 (2021).

Zhang, T., Mao, Z. & Wang, T. GIS-based evaluation of landslide susceptibility using a novel hybrid computational intelligence model on different mapping units. J. Mt. Sci. 17, 2929–2941 (2020).

Chen, C. Y. Event-based rainfall warning regression model for landslide and debris flow issuing. Environ. Earth Sci. 79, 127 (2020).

Asmare, D., Tesfa, C. & Zewdie, M. M. A GIS-based landslide susceptibility assessment and mapping around the Aba Libanos area, Northwestern Ethiopia. Appl. Geomat. 15, 265–280 (2023).

El-Rawy, M., Elsadek, W. M. & De Smedt, F. Flood hazard assessment and mitigation using a multi-criteria approach in the Sinai Peninsula, Egypt. Nat. Hazards 115, 215–236 (2023).

Han, Y. S. et al. Assessment of secondary mountain hazards along a section of the Dujiangyan Wenchuan Highway. J. Mt. Sci. 11(1), 1–10 (2014).

Dou, J. et al. An integrated artificial neural network model for the landslide susceptibility assessment of Osado Island, Japan. Nat. Hazards 78, 1749–1776 (2015).

Ma, Z. & Mei, G. Deep learning for geological hazards analysis: Data, models, applications, and opportunities. Earth Sci. Rev. 223, 103858 (2021).

Abdollahi, S., Pourghasemi, H. R., Ghanbarian, G. A. & Safaeian, R. Prioritization of effective factors in the occurrence of land subsidence and its susceptibility mapping using an SVM model and their different kernel functions. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 4017–4034 (2019).

Pouyan, S. et al. A multi-hazard map-based flooding, gully erosion, forest fires, and earthquakes in Iran. Sci. Rep. 11, 14889 (2021).

Zhang, K., Wu, X., Niu, R., Yang, K. & Zhao, L. The assessment of landslide susceptibility mapping using random forest and decision tree methods in the Three Gorges Reservoir area, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 76, 405 (2017).

Yang, L., Cui, Y., Xu, C. & Ma, S. Application of coupling physics-based model TRIGRS with random forest in rainfall-induced landslide-susceptibility assessment. Landslides 21, 2179–2193 (2024).

Kikuchi, T., Sakita, K., Nishiyama, S. & Takahashi, K. Landslide susceptibility mapping using automatically constructed CNN architectures with pre-slide topographic DEM of deep-seated catastrophic landslides caused by Typhoon Talas. Nat. Hazards 117, 339–364 (2023).

Yu, X. & Chen, H. Research on the influence of different sampling resolution and spatial resolution in sampling strategy on landslide susceptibility mapping results. Sci. Rep. 14, 1549 (2024).

Tsunetaka, H. et al. Variation in rainfall patterns triggering debris flow in the initiation zone of the Ichino-sawa torrent, Ohya landslide, Japan. Geomorphology 375, 107529 (2021).

Shu, H. & Zhang, F. Susceptibility assessment of soil-water hazard chain on a small catchment in gully region of Loess Plateau: Implications for artificially-induced mountaintop removal filling valley and geoheritage. Geomorphology 444, 108949 (2024).

Zhao, W. et al. A regional early warning model of geological hazards based on big data of real-time rainfall. Nat. Hazards 116, 3465–3480 (2023).

Ning, Z., Tie, Y., Sun, C. & Xu, W. Geohazard susceptibility mapping considering spatial heterogeneity: A case study of Xide County in Sichuan Province. Nat. Hazards 1, 1 (2024).

Oguz, E. A., Depina, I. & Thakur, V. Effects of soil heterogeneity on susceptibility of shallow landslides. Landslides 19, 67–83 (2022).

Shafapourtehrany, M., Yariyan, P., Özener, H., Pradhan, B. & Shabani, F. Evaluating the application of K-mean clustering in earthquake vulnerability mapping of Istanbul, Turkey. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 79, 103154 (2022).

Huang, F. et al. Landslide susceptibility mapping based on self-organizing-map network and extreme learning machine. Eng. Geol. 223, 11–22 (2017).

Milošević, D. et al. Artificial neural networks as an indicator search engine: The visualization of natural and man-caused taxa variability. Ecol. Indic. 61, 777–789 (2016).

Kim, H. G. et al. Spatial patterning of chlorophyll a and water-quality measurements for determining environmental thresholds for local eutrophication in the Nakdong River basin. Environ. Pollut. 268, 115701 (2021).

Huang, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal distribution patterns of deadly geohazard events in China, 2013–2019. Nat. Hazards Res. 2(4), 316–324 (2022).

Nemerow, N. L. Scientific Stream Pollution Analysis (McGraw-Hill, 1974).

Kohonen, T. Self-organized formation of topologically correct feature maps. Biol. Cybern. 43(1), 59–69 (1982).

Bação, F., Lobo, V. & Painho, M. Geo-self-organizing map (Geo-SOM) for building and exploring homogeneous regions. In Third International Conference on GIScience 22–37 (Springer, 2004).

Wang, Y. et al. A hybrid model considering spatial heterogeneity for landslide susceptibility mapping in Zhejiang Province, China. Catena 188, 104425 (2020).

Vesanto, J. & Alhoniemi, E. Clustering of the self-organizing map. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 11, 586–600 (2000).

Davies, D. L. & Bouldin, D. W. A cluster separation measure. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1(2), 224–227 (1979).

Xiao, T. et al. Spatial prediction of landslide susceptibility using GIS-based statistical and machine learning models in Wanzhou County, Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Acta Geochim. 38, 654–669 (2019).

Wu, X. et al. Effects of soil type and rainfall intensity on sheet erosion processes and sediment characteristics along the climatic gradient in central-south China. Sci. Total Environ. 621, 54–66 (2018).

Pradhan, B. & Lee, S. Landslide susceptibility assessment and factor effect analysis: Backpropagation artificial neural networks and their comparison with frequency ratio and bivariate logistic regression modelling. Environ. Model. Softw. 25(6), 747–759 (2010).

Di Maggio, C., Madonia, G. & Vattano, M. Deep-seated gravitational slope deformations in western Sicily: Controlling factors, triggering mechanisms, and morphoevolutionary models. Geomorphology 208, 173–189 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2023JJ30238), the Open Fund of Hunan Geological Disaster Monitoring, Early Warning and Emergency Rescue Engineering Technology Research Center (No. hndzgczx202409), and the Research Project on Natural Resources of Hunan Provincial Department of Natural Resources (No. HBZ20240112).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Weifeng Xiao: Writing—original draft, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition. Ziyuan Zhou: Data curation, software development and implementation, figures preparation Bozhi Ren: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Validation. Xinping Deng*: Resources, Data curation, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript and have given their consent for its submission to Scientific Reports. The corresponding author, Xinping Deng, can be contacted for any further inquiries regarding the study or the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, W., Zhou, Z., Ren, B. et al. Integrating spatial clustering and multi-source geospatial data for comprehensive geological hazard modeling in Hunan Province. Sci Rep 15, 1982 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84825-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84825-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Incorporating Big Data of Public Service Facilities into Flood-seismic Exposure Assessment in China

Chinese Geographical Science (2025)