Abstract

In smart applications, streaming IoT data is essential to building trust in sustainable IoT solutions. However, most existing systems for storing and disseminating IoT data streams lack reliability, security, and transparency, primarily due to centralized architectures that create single points of failure. To address these limitations, this research introduces TraVel, a blockchain and transfer learning-based framework for secure IoT data management. TraVel leverages decentralized IPFS storage to handle large data volumes effectively, integrating with a private Ethereum blockchain to enhance data integrity and accessibility. In the proposed scheme, the smart home (\(SH_m\)) data is collected securely and accessed over the BC with a unique hash key generated on the IPFS for all the files. Self-executing Ethereum smart contracts enforce access control and verify data integrity, allowing only validated, non-malicious data to be stored. An adversarial domain adaptation (DA) learning model is employed to detect and filter malicious data before it enters the blockchain. TraVel’s performance is evaluated on blockchain parameters, with simulations conducted on REMIX IDE and InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), demonstrating its reliability and scalability for secure IoT data dissemination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In present times, it is hard to accept the world without the Internet witnessing how it has transformed society. Now, it has expedited the process of connecting every entity across the world to the Internet. The transition from being things to smart things is centered on the fusion of the Internet with innovative technologies1. With this proliferation, it becomes necessary to have constant control over these smart devices. The literature manifests that the infantile smart world is now more vulnerable to penetrations and attacks due to the increased depth of the digital pool with ever-increasing smart nodes. Further, the growing depth of smart nodes, estimated to be 41.6 billion in the year 2025, has the capability to produce data of 79.4 zettabytes2. The real value of smart application lies in the integrity of that data. Because IoT devices are often located in remote or harsh environments, they may be subject to various types of interference or tampering, which can compromise the integrity of the data they generate. Furthermore, insecure communication channels are used with even no mechanisms to secure data at the storage level. In addition to data integrity, there is also a growing concern about trust in IoT data. This is because IoT devices often generate data that is used to make critical decisions, such as in healthcare, transportation, and industrial settings. If this data is inaccurate or unreliable, it can have significant repercussions, such as incorrect diagnoses, accidents, or equipment failure.

The evolving cyber surfaces have now included our houses, that have grown smart in recent years, thereby compromising our privacy. This highlights the importance of smart services and intelligent schemes has become questionable. Security and privacy have become the main concerns for a sustainable IoT, especially in critical infrastructure. All the smart things, whether they are automobiles or other physical devices, are embedded with sensors, and thus, they exchange sensed data over the network. These IoT data streams are valuable assets, posing challenges like security and privacy. Thus, it is a necessity to ensure a secure and trusted way of disseminating IoT data streams. Although cryptographic methods are widely utilized in securing communication, the security of these techniques depends on how hard it is to decipher the encrypted data feeds. But smart motes could only use simple cryptographic techniques because they don’t have enough computing power. On the other hand, potential adversaries can easily break lightweight cryptographic schemes. Hence, cryptography is not a viable solution for the IoT. So, the IoT needs to switch to a different, more reliable technology for sending or receiving data in a secure way. The IoT streaming devices are often connected with the centralized servers for data analysis in order to extract value from the data collected by the devices. The security of the system for access control may be jeopardized by centralization because of the single point of failure issue. But it’s crucial to grant users access rights to IoT data streams. To address this issue, the smart contract for self-executing access checks is deployed on the Ethereum BC. The existing literature reveals that there is a lack of data checks at the initial point, i.e., before adding the data in the blockchain. Thus, there is need to ensure only non-malicious data feeds are added in the blockchain.

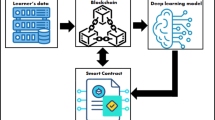

In this work, a BC and TL-based scheme known as TraVel has been proposed to deal with the aforementioned concerns. BC is no longer just used to transfer money using cryptocurrencies like bitcoin and ethers without the use of a bank. Nowadays, BC is regarded as a key technology for any applications that require privacy with immutability and traceability, via a distributed ledger with cryptography, and safe transactions. The proposed TraVel scheme ensures the delivery of the data stream in a secure, decentralized, and reliable way. It is further divided into two parts: (i) Ensuring storage of non-malicious data on Ethereum BC with TL based learning approach. (ii) Secure data dissemination with private Ethereum BC and offchain storage on IPFS.

The proposed scheme uses the distributed ledger’s visibility, immutable logs, and integrity of data to let users access IoT data streams reliably. Also, the provision of signed transactions in BC ensures non-repudiation and accountability. Additionally, we incorporate off-chain decentralised storage into our scheme to make it easier to store IoT data chunks securely. Further, the proposed scheme uses Ethereum SCs to store the system’s programmable logic. Every time a function is executed, a transaction is created and added to the tamper-proof logs. We only store data chunk hashes, streamed data time-stamped indices, and chunk numbers in our on-chain storage. This is done to prevent the high expense of on-chain storage and to make sure that the hashes are unchangeable and easier to track3. Table 1 shows the acronyms used in this manuscript.

Following are the contributions of this research work.

-

Firstly, we developed an intelligent BC-based scheme, to securely disseminate IoT data streams in smart home (\(SH_m\)) environment.

-

Then we used the decentralised IPFS storage in our Ethereum BC-based scheme to address the issue of storing the large volume of data over the BC. \(SH_m\) data is collected securely and accessed over the BC with a unique hash key generated on the IPFS for all the files. It is considerable feature of BC and IPFS that they work in one way making it impossible to get the primary data from their respective hashes.

-

Next, we created self-executing Ethereum SCs to enforce access rights over the BC and to ensure only non-malicious data feeds are stored in the Ethereum BC. To detect the maliciousness of the data, we employed adversarial learning model to ensure malicious data is not stored in the Ethereum BC.

-

Finally, the performance of TraVel is evaluated based on BC parameters (SC deployment cost, data feeds storage cost, transactions cost in terms of gas) simulated on REMIX IDE and IPFS. Besides, the efficacy of the TL-based learning model is evaluated on parameters, for instance, accuracy, loss, recall, precision, F1-score, and AUC score.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section “Related work” highlights the related works, followed by background to understand the proposed TraVel scheme in section “Background”. Section “System model and problem formulation” discusses the system model and the problem formulation of TraVel scheme. Section V presents the proposed scheme. Section “TraVel: the proposed scheme” discusses the performance evaluation of the proposed system and finally, section “Conclusion” concludes the paper.

Related work

The literature manifests that securing data communication is mainly focused on the cryptographic techniques. In cryptographic techniques, there is secret writing in which the sender encodes the message in the form which only the intended receiver can decode. Although, these techniques are widely employed for securing communications in general. However, this is not the reliable way for securing communications in network of resource constrained nodes of smart applications. And in IoT nodes, only lightweight cryptographic techniques could be implemented, making data easy targets for adversaries.

To cope with these challenges, BC has been worked upon as a potential ground for secure communication in smart applications. It is the distributed ledger in the form of immutable blocks which are cryptographically chained together with hashes. Also, the significant research is going to use mechanisms covering both BC and federated learning headed under the hybrid approaches. This section reviews the pertinent works related to our domain in the proposed scheme. To enable safe data sharing in a health sector, Hasan et al.3 proposed a framework that combines BC with Software-Defined WANs and implemented a SC-based access control strategy. Following this work, Yang et al.4 proposed another BC-based data sharing model for industrial IoT under the name, EdgeShare, with the SC to form access control policy. In the same line, Miao et al.5 proposed a model sharing framework for secure data sharing by employing federated learning and BC for recording the training process. In the following year, R Hasan et al.6 proposed a BC and IPFS-based framework for IoT streaming devices and employed a proxy re-encryption network to preserve the privacy of the IoT streamed data. With this, Singh et al.7 proposed a centralized data sharing model in cross-domain for product manufacturing by employing multiple security gateways.

In the same line, Manogaran et al.8 proposed BC-based secure data sharing scheme for smart industry ensuring both inbound and outbound security. Following this, Pranto et al.9 devised BC and SC based scheme to automate the pre and post harvesting under the smart agriculture, so as to bring the trust among farmers, consumers, and other intermediaries. In another work, Gupta et al.10 proposed a BC-based secure data sharing scheme for network of unmanned aerial vehicles. Following this, M.A Khan et al.11 proposed a BC-based resource-efficient smart home architecture to ensure secure data dissemination, empowering with Deep Extreme Learning Machine. In line, Aggarwal et al.12 proposed a model for the internet of drones which provides secure communication, data collection, and transmission among drones and users with a public BC.

Background

It gets difficult to fully understand how the proposed BC and TL-based TraVel scheme works without a good comprehension of some fundamental terms. These terms are explained below.

-

Blockchain: It is an immutable distributed digital ledger, which stores data/transaction in the blocks that are cryptographically linked with each other. The first block in the BC is called the genesis block i.e., block 0. For ever-growing chain of blocks, this procedure can be performed indefinitely many times. Figure 1 illustrates how blocks are chained together. The previous block’s hash value is stored in each new block, thus if the contents of a preceding block are altered, the value of the previous block’s hash will change and will no longer match the hashes stored in any new blocks. The BC copy of the user who makes the update will not match with data of other users when this chain is propagated13.

-

Transaction: The transfer of data/values on the BC, is called a transaction. To perform a transaction, we need to have an ethereum account just like a bank account that has some wallet associated with it and thus, the ethers. As to perform the transaction, one needs to pay in the form of gas, the fee for processing and further validating the transaction on BC. After the transactions of different clients are requested, initially they all are pilled up in the memory pool. Then the transactions are selected from mem pool and broadcasted to the miners for verification. Once they are validated against certain conditions set by the peers of the BC network, they are added in the block. Then the block is sealed with its unique hash key and chained with the existing BC creating a ledger when other nodes in the BC network validate its hash14. This process of transaction in BC is shown in Fig. 2.

-

Private Ethereum BC: Ethereum is a kind of BC that facilitates you to run SC. In TraVel, we use the private blockchain in which data stored in blocks is private i.e., not visible to everyone for reading and writing. This essentially means that an Access Control Layer is created over a standard BC to exert control over who is permitted to read or publish data to the BC. The cryptocurrency utilised by Ethereum is called ether, and it may be used to send money as well as to buy gas for running smart contract15.

-

Consensus Protocol: A block of transactions is created and added to the Ethereum BC network through the process of mining. At present, it makes use of the Proof-of-Stake (PoS) consensus algorithm. A consensus algorithm is a process which ensures every peer in the BC network to agree on the current state of the decentralized distributed ledger. As there is no centralized body in crypto network, so there must be some mechanism to validate the transactions16. Thus, transactions are validated by the peers of the BC network and for this they need to put significant effort to prove their willingness to attest the transaction’s validity. In PoS, the miner is randomly selected who has to stake his entire funds in the form of ethers into a SC for mining the block. At certain checkpoints, if two third of the nodes validate the present state of the block, then finally added to the blockchain16.

-

Cyptocurrency: Ethereum rewards successful miners with a cryptocurrency called ether. This can be broken into smaller units up to the smallest possible unit, which is termed a wei. To perform any operation on the ethereum BC, we have to pay in terms of gas. There is reasonable amount of gas limit being set to perform the operations in the BC. Miners are unlikely to process that transaction if the limit is set too low. Once the transaction has been completed, the miner who processed it will be compensated in ether equal to the amount of gas used. The account from which the transaction was requested receives the remaining amount of the gas17.

-

Smart contracts: It is a piece of code written in a particular programming language, such as Solidity, that executes itself when certain criterion’s are met. SC on the BC eradicates the necessity for trustworthy third-party systems to maintain the relationship of trust between the involved parties. On addition to facilitating financial transactions, these SCs are employed to store significant data in a distributed ledger. Figure 3 illustrates the execution of a SC. Methods in the SC are treated as a transaction and thus, could be executed by only those nodes who can pay for running that transaction18.

-

Ethereum Account and Ethereum Address: An Ethereum account is just like a bank account through which we can store, transfer, receive, and use ethers(crypto-currency) to execute SCs. To every Ethereum account (EA), an ethereum address (20 bytes) is linked, generated from the SHA3 hashed public key. EA can be controlled by code i.e., contract account or anyone with the private key i.e., externally owned accounts (EoA). For every contract we deploy to Ethereum BC the contract account is created, that has a unique address from where the contract code is executed. However, no private key is associated to them. EAO are the one which have the private key associated with the Ethereum address19.

-

Encryption and EVM: Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) is used by Ethereum to create public and private keys, while ECC-based digital signatures are used to validate and sign transactions. The public-private key pair is created using the two selected points. The public key is hashed using the Keccak-256 algorithm, a variant of SHA-3, and the rightmost 20 bytes are recorded as the Ethereum address while transactions are signed by the private key. An Ethereum virtual machine is a node (computer) connected to the Ethereum BC network20.

-

IPFS: IPFS is a distributed decentralized file sharing system, in which the stored data is accessed by content addressing. It has similar properties like BC i.e., its immutable and decentralized. It uses distributed hash table (DHT) and merkel directed acyclic graph (DAG) to store and retrieve the files. When the file will be uploaded in IPFS, it is divided into chunks which stores either the data or link to other chunks. Then for each chunk, a cryptographic hash is generated which forms the merkel (DAG), describing the complete file. Once the merkel DAG has been formed, the entire file can be accessed only by its root hash. Thus, corresponding to each data file stored in IPFS, a hash is generated through which one can further access that file21.

Transfer learning in TraVel

Transfer learning is referred to as the learning process in which a model is learned on one source domain or task whereas evaluated on another, related target task or domain, such that either the domains or tasks (or both) differ22. For instance, we might want to train a model using a dataset of handwritten digits (like MNIST23) to identify home numbers. Two basic terms, ‘domain’ and ‘task’ are used to define different TL schemes. A domain is made up of the features of the data (i.e., feature space) and how they are distributed throughout the dataset (i.e., marginal probability distribution). An objective predictive function (i.e., a function learned from the training dataset) and a label space (i.e., a collection of labels) define a task. Pan and Yang used the terms: “inductive,” “transductive,” and “unsupervised” for categorizing TL methods depending upon whether the task or domain differed between the source and target. In inductive TL, there are different source and target tasks, whereas the domains might not differ, and it is necessary to have some target-labeled data. In transductive TL, there are different source and target domains, whereas the tasks are the same, and it is necessary to have source-labeled data and target unlabeled data. In unsupervised TL, there are different source and target tasks, but it is not necessary to have labeled data in either of the domains. Figure 4 demonstrates the different techniques of TL.

Domain adaptation

A form of transductive TL is domain adaptation. Here, the source and target tasks are the same, but the domain is different. Further, DA is of both homogeneous and heterogeneous types. In the case of homogeneous DA, the feature space of both domains is also the same, while in the case of heterogeneous DA, the feature spaces are different. With respect to the availability of labeled target data, DA is further divided into three types. In supervised DA, labeled data in both the source and target domains is required. In unsupervised DA, labeled data in the source domain and unlabeled data in the target domain are required. In semi-supervised DA, labeled data in the source domain and some labeled target domain data are required. These categories are distinguished based on the target domain, with the assumption that labeled source data is available. Numerous novel unsupervised DA techniques have been put out recently, with an increasing focus on NN-based strategies. Different research strands have developed. These include mapping between domains, separating normalization statistics, constructing ensemble-based approaches, aligning the source domain and target domain distributions, and focusing on rendering the model target discriminative by shifting the decision boundary towards areas of lower data density.

Domain-invariant feature learning

When features in a feature representation exhibit the same distribution whether the input data comes from the source domain or the target domain, the feature representation is said to be domain-invariant. A classifier tends to generalize successfully to the target domain if it is trained to predict correctly on the source data by employing domain-invariant features, as the target data’s features correspond to those used in the training process. In this learning process, different methods align the domains in different ways. Some apply adversarial training, some do the reconstruction process, and others minimize divergence. In most cases, a domain classifier makes up the alignment component. A domain classifier determines whether the feature representation was created from source data or target data in its output. To accurately predict the domain, the domain classifier is being trained. In this case, the feature extractor has been trained in a way that prevents the domain classifier from correctly identifying the domain from which the feature representation came. Like GAN, these networks are often adversarially trained by switching between these two steps. For example, Domain Adversarial Neural Network (DANN)24. The other way in which an alignment can be achieved is through reconstruction. In this, it works on learning a representation that can classify the labeled source domain data and be applied to reconstruct the target domain data, or even both. In these setups, the alignment component is a reconstruction network, contrary to the feature extractor, and takes the output of the feature extractor and recreates its input24. By minimizing a divergence, which determines the distance among the distributions, one can also align the distributions. MMD, correlation alignment, contrastive domain discrepancy, and the Wasserstein metric are methods for the divergence measure. A two-sample statistical test that determines whether two distributions are identical by considering the observed samples over the two distributions is known as the MMD. The test is defined by comparing the mean values obtained from the smooth function on samples from the two domains. The samples are probably not drawn from the same distribution if the means differ. The unit balls in characteristic reproducing kernel Hilbert spaces (RKHS) were chosen as the smooth functions for MMD, since it can be demonstrated that the population MMD is zero provided the two distributions are equivalent. The alignment component of MMD can be another classifier that is comparable to the task classifier in order to employ MMD for domain adaptation. MMD can then be calculated and minimized between the layer’s outputs from these classifiers.

Adversial training with DANN

DANN is a technique for feature-based DA. There are three NN networks in this adversarial architecture, i.e., an encoder network (E), the discriminator network (D), and the task network (T). The DANN works by employing the encoder network to find a new feature representation for source and target domain features. The encoder network is trained in an adversarial fashion, and parallelly, the discriminator network is trained to distinguish whether the new generated features belong to the source domain or the target domain. In addition to the encoder and discriminator networks, a task network is also being trained on the new domain-invariant features to predict the class labels of the target data. The DANN model is trained in order to reduce total adversarial loss and task loss during training. This promotes the model to learn features that are applicable to the given task and domain-invariant. The task loss function, such as cross-entropy loss, assesses the difference between the labels that were predicted and the truth labels for the training data. The feature extractor and task classifier minimize this loss function during training. The adversarial loss, i.e., the binary cross-entropy loss, seeks to reduce the discriminator’s capacity to accurately anticipate the input samples domain labels. In other words, it aims to render the domain classifier unable to discriminate between the feature representations of the source and target domains. This encourages the learning of traits that are more resilient across many domains and are not biased towards any one particular domain. The extracted features are essentially made domain-invariant at the same time the feature extractor is trained to minimize the domain classification loss. A reversal gradient layer, positioned between the encoder and the discriminator, is used for the adversarial training. The gradient sign in backpropagation has been reversed in this layer, which allows the two networks to be optimized for two opposing objective functions.

System model and problem formulation

This section covers the proposed scheme’s system model and the problem formulation of the designed system model. Table 2 presents the symbol table for TraVel scheme.

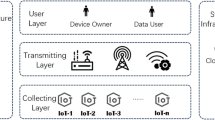

System model

Figure 5 shows the system structure with TL for checking the status of the sensed data of getting being malicious in a \(SH_m\) environment and ethereum private BC (\(B_{PE}\)) for secure data dissemination. The following entities i.e., \(SH_m\), \(N_w\), \(E_u\), \(E_n\), \(B_{PE}\), \(E_W\), IPFS, \(TL_m\), \(D_St\), \(D_{Fl}\),\(B_T\), \(H_{Fl}\) with 6G communication channel are the part of this system. Every entity is interconnected via \(B_{PE}\) and have their ethereum accounts. The \(SH_m\) application comprises multiple IoT nodes (\(E_n\)) connected via a network (\(N_w\)). These networks have been the victim of known and unknown attack variants25. From the literature studied, it is revealed that unknown attack variants could be detected by leveraging the knowledge from known attack variants. The TL-based model (\(TL_m\)) with the learning classifier is used to label the data \(D_l\) as malicious or non-malicious. The data feeds from \(SH_m\) network is recorded in the \(B_{PE}\) to ensure data integrity and privacy. However, instead of storing all the data directly in \(B_{PE}\), the data is stored in the IPFS storage. IPFS returns the hash values \(H_{Fl}\) for the stored data, which are further stored in \(B_{PE}\). The users access the data from the BC via the IPFS hash. To ensure user and node authentication, we employed the SCs whose bytecode is stored in \(B_{PE}\). As of now, smart home is the most adaptable structure, we cannot afford delays. This could mean that things that happened in a particular order in the real world, could appear to have happened in a different order at the controller (where the decisions are made). We employed a 5G communication network to enhance network performance in terms of latency and reliability.

Problem formulation

The significant goal of this study is to boost data security during the data dissemination among IoT nodes (\(E_u\)) and \(SH_m\) users (\(E_n\)). In the proposed TraVel scheme, entities {\(E_u, E_n\} \in E\) communicate with each other via peer-to-peer distributed approach. \(E_u\) have maximum p number of users accessing the \(SH_m\) network and \(E_n\) have maximum q number of \(SH_m\) devices installed over the home network. For all \(\zeta _k\) requests, data transfer among \(E_u\) and \(E_n\) are based on the following constraints.

Here entities {\(E_u, E_n\)} cannot be \(\phi\). The next constraint shows that all entities {\(E_u, E_n\)} should have a ethereum wallets {\(EW_u, EW_n\)} to ensure secure data dissemination using private blockchain \(B_{PE}\). Also, all entities {\(E_u, E_n\)} must be registered \(R_d\) within the smart contract \(SC_{Rd}\).

Also, data undergoes security checks via \(TL_m\) based classifier \(CL_t\) to ensure only non-malicious data feeds are uploaded in the private blockchain. \(TL_m\) is trained with data \(D_t\) from the \(SH_m\) network. The data \(D_t\) undergoes various stages of preprocessing (removing outliers, working on missing values,and normalizing) before being feeded to \(TL_m\).

Here, we use the transductive transfer learning model \(TL_m\) to transfer the knowledge of known attacks \(K_m\) from the source domain i.e., \(S_C \in E_d\) to detect the zero-day attacks \(Z_r\) in the target domain i.e., \(T_G\). And the classifier \(CL_t\) defined by the target predictive function \(P_t(.)\) with least expected error \(E_{rr}\) on \(D_{test}\), the set of feature values predicts the binary output values i.e. \((B_0^1)\) after binary classification given by

Then, their predicted values are sent to the smart contract \(SC_{DEC}\), which ensures to store only the non-malicious data and from the registered entities. All entities interact with each other through their ethereum accounts EA. The structure of EA’s of the entities is represented as follows.

All entities {\(E_u, E_n\)} communicate through wireless communication channel \(Ch_{wl}\) ensuring minimum latency (\(L_{Tcy}\)) over the 5G channel. Thus, the important parameter of the TraVel scheme, the round trip latency \(RTL_{wl}\) of different \(Ch_{wl}\) are shown as below.

Equations (11) and (12) represent the communication delay in LTE and 5G networks, which is \(\le\) 10 ms and < 1 ms respectively.

The mathematical formulation of the problem as per the designed system model of TraVel scheme is represented as follows:

subject to constraints

Here, \(Sec \rightarrow \{\sum _{i=1}^{24} D^k_i\}\) shows the secure data dissemination of hourly produced data feeds among \(SH_m\) nodes and users. \(Sec \rightarrow \{W^k_j\}\) shows the security of ethereum accounts of participating entities preventing node cloning. Then, \(LT_{cy}\) shows the round trip latency of wireless communication channel \(Ch_{wl}\) to be minimum. At last, \(CL_t(ERR)\) shows the least expected error by the TL-based classifier while classifying the data as malicious/ non-malicious.

Furthermore, constraint C1 shows the data dissemination between \(SH_m\) users and IoT nodes. Next, constraint C2 illustrates the electronic wallets of \(SH_m\) users and IoT nodes required for communication. The constraint C3 shows that hourly produced data feeds, i.e., \(D^k_i\) should be more than zero and wallets of entities {\(E_u, E_n\)} must have ethers to perform transactions. At last, constraint C4 illustrates that there must be one user and IoT node communicating with each other.

TraVel: the proposed scheme

Figure 6 shows the proposed learning and BC-based intelligent and secure data dissemination scheme for smart home underlying a 5G environment called TraVel. The TL-based learning algorithm tells whether the received data from the \(SH_m\) network is malicious or not, which decides its reliability. In contrast, SCs stored in BC ensures only non-malicious data from authenticated entity is stored in and accessed from BC. The TraVel is virtually ramified into three different layers, such as (i) smart home layer, (ii) learning layer, and (iii) blockchain layer, elucidated as follows.

-

(A)

Smart home layer: A smart home is a living space that is outfitted with a variety of technologies to enable users to access and manage systems and appliances from virtually anywhere and at any time. For this reason, \(SH_m\) interact in real-time, whether it’s delivering the user camera feeds or sensor data, or accepting the user’s temperature-setting request. Communication between the smart home’s gadgets and the related environments is what make these intelligent services possible25. In the proposed TraVel scheme, the smart home is devised with items such as smart bulbs, an ecobee thermostat, an Enno doorbell, IP cameras, a smart lighting system, a smart door lock, several sensors, and an amazon echo plus. As they are all connected directly to a gateway providing remote access, the user can access these devices from his mobile application. Each smart device contains a number of assets (\(A_t\)) that the adversaries are after. These assets include firmware, network, login credentials, essential resources, system configuration files, digital certificates, and special keys. However, these gadgets are easy for potential adversaries to play with as they have serious inherent vulnerabilities. The fundamental operation of a smart gadget can be interfered with by maliciously altering the integrated circuit employing hardware trojan. Even the side channel statistics about the device, such as power dissipation, processing speed, and power consumption, might be used to construct the secret keys. Additionally, one can actively listen in on communication lines to get control data such as shared network passwords, node configurations, and identities26. Therefore, it is important to handle the assets of the smart home environment carefully, both physical and digital.

-

(B)

Learning layer: TraVel employs transductive TL, to use the knowledge already acquired through the process of learning known threats, across unknown threats in \(SH_m\), as a simple binary classification problem, labelling the occurrences as benign or threat. It accepts the network traffic traces as input from the \(SH_m\) gateway. To improve the prediction accuracy in threat detection, the labelled source data (\(U_d\)) and unlabeled target data (\(Un_d\)), with n values, go through data cleaning and preprocessing. The steps involved in the data cleaning process are elucidated as follows.

$$\begin{aligned} \varphi ~= ~Q^r_3~-~Q^r_1 \end{aligned}$$(18)$$\begin{aligned} Q^r_1~= Med~ \left[ 1,\frac{n}{2} \right) \end{aligned}$$(19)$$\begin{aligned} ~Q^r_3~=~Med~ \left[ \frac{n}{2}~ + ~1,n \right] \end{aligned}$$(20)where \(\varphi\) is the inter-quartile range, or midspread, which eliminates outliers from the data. The median of the ordered dataset’s lower half is represented by the first quartile \(Q^r_1\), its middle value is represented by the second quartile \(Q^r_2\), and its upper half is represented by the third quartile \(Q^r_3\).

$$\begin{aligned} \zeta _j~=~ \frac{fe_j- max(fe_j)}{max(fe_j)-min(fe_j)} \end{aligned}$$(21)where \(\zeta _j\) is the feature’s normalised value, bringing the feature’s numerical value to a range between 0 and 1. Additionally, given a range, \(max(fe_j)\) and \(min(fe_j)\) return the maximum and least value in \(fe_j\). The categorical features in the sample are then given binary values \((H_0^1)\) using one hot encoding.

$$\begin{aligned} G ~ \xrightarrow {\Phi } ~H_0^1 \end{aligned}$$(22)where G represents the group of categorical feature values, \((H_0^1)\) is the output binary values following one-hot encoding, and \(\Phi\) denotes the conversion relation. Following the pipeline, this phase of the TraVel scheme is carried out in four steps. (i) First gather the labelled source data, which represents known risks, and the unlabeled target data, representing unknown threats, from their associated repositories . This data then passes through a number of pre-processing stages before being used as an input for learning models; (ii) To achieve domain adaptation across both domains and to create a new feature representation, DANN model is trained in the adversarial manner. For this, loss functions, such as the domain loss and task classification loss are determined, and the weights of different NNs are updated until the global objective function is achieved; The task classifier is then trained using the source labelled data with the updated feature representation; (iv) Once the model has been trained using the new feature space, it will be able to predict the class labels of newly acquired unlabeled target data. Given source \(D^l_s\) and target domains \(T^u_s\) , similar source \(T^k_s\) and target tasks \(T^k_t\) with labeled traffic data \(L_d\) and unlabeled traffic data \(U_d\), the transductive TL is employed to learn the target predictive function \(P_t(\xi )\) from \(L_d\) and \(U_d\) data as represented below to accurately predict the labels of target data \(D_t\).

$$\begin{aligned} D^l_s~ = ~\{(fe_1,l^b_1), (fe_2,l^b_2),\dots (fe_n,l^b_n)\} \end{aligned}$$(23)$$\begin{aligned} T^u_s = \{fe_{n + 1}, fe_{n+2},\dots , fe_{n+m}\} \end{aligned}$$(24)$$\begin{aligned} P_t(\xi ) ~:~ fe_t~\rightarrow ~ l^b_t \end{aligned}$$(25)Subject to constraints

$$\begin{aligned} C1: D^l_s ~\ne ~T^u_s~ ~or~ ~M_ds(fe_s) ~\ne ~M_dt(fe_t) \end{aligned}$$(26)$$\begin{aligned} C2:T^g_s ~= ~T^k_t~ \end{aligned}$$(27)$$\begin{aligned} C3:~ L^b_s~=~L^b_t \end{aligned}$$(28)Here,the constraint C1 shows that either the source and target domain should be different or their marginal distributions. The next constraint C2 illustrates that source and target tasks must be same. The last constraint C3 shows that labels of both source and target data must be same.

-

(C)

Blockchain layer: TraVel considers the private BC i.e., Ethereum, a decentralised distributed ledger for secure data dissemination in \(SH_m\). It guarantees reliable and secure communication among the parties \(E_u, E_n\) taking part in the \(SH_m\) environment. It is hard to manipulate the blockchain because every newly mined block is added after the current blockchain using the preceding block’s hash value, which is a one-way function27. The hash \(H_k\) of \(k_{th}\) block is calculated as follows.

$$\begin{aligned} H_k = \{H_{k-1} \oplus T_m \oplus Nonce\} \end{aligned}$$(29)where \(H_k\) is the hash of the chain’s previous block. The \(k_{th}\) block’s nonce value is represented by Nonce and the timestamp for the block is \(T_m\). The block comprises of block header and block body with the following information as shown below.

$$\begin{aligned} B^l_{header} = \{B^l(Version,Nonce,Timestamp, DifficultyLevel),Hash(Merkel,H_{k-1},H_k)\} \end{aligned}$$(30)$$\begin{aligned} B^l_{body} = \{T^s_c(counter),(T^s_{c1},T^s_{c2}.....,T^s_{cN})\} \end{aligned}$$(31)Additionally, with SCs, \(B_{PE}\) ensures control and centralization over the \(SH_m\) network by allowing only registered IoT devices and end-users to store and retrieve data from the BC. Thus, preventing unauthorised access to \(SH_m\) data feeds and network. To achieve this, we have the data verification stage followed by storing data in a distributed manner to ensure secure data collection and storage. Data exploitation is further decreased with the transparency feature of BC. Presently, storing large amount of data in ethereum BC is costly affair due to several calculations and hash-key verification to protect the BC’s integrity. Therefore, the proposed TraVel scheme employed an IPFS storage system to store the actual data feeds of \(SH_m\) network, while \(B_{PE}\) stores the links to those actual data feeds of system. As discussed above, TraVel has several entities associated with the \(B_{PE}\) SC. Figure 7 describes the secure data dissemination via the sequence diagram. In this layer, \(i^{th}\) \(SH_m\) node and \(j^{th}\) user are registered with SC by the administrator. Also, it stores the status of \(SH_m\) data feeds in SC. If the status of these data feeds is non-malicious, then they are stored in IPFS and their corresponding hashes received from IPFS are stored in \(B_{PE}\). In order to retrieve the data, blockchain first verifies the user and then gives the hash of the requested data feeds to access the data from IPFS, an offline storage. For malicious data and unauthorized user access, an event is fired. Algorithm 1 describes the detailed secure data dissemination procedure in \(SH_m\). Algorithm 3 checks whether an entity is part of the network and registered over the network. Algorithm 4 shows the access control over the BC as only the administrator can remove an entity from the network.

Performance evaluation

This section covers the performance evaluation of the proposed TraVel scheme. There are five subsections in this part that assesses the performance: adversarial learning classifier evaluation metrics, BC simulation gas profiler, SC interface, anticipated model comparison in terms of storage cost.

Experimental setup and dataset description

The proposed TraVel scheme is evaluated on 64 bit system configured as, Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-8565U CPU @ 1.99 GHz with 4 cores, 16 GB RAM, and 8 MB cache. We used Windows 11 version 22H2 (19045.2364), Jupyter notebook, Remix IDE, and IPFS for simulating/implementing the TraVel scheme. And the Python language for implementing and evaluating the integrated adversarial model in TraVel scheme. To train TL-based model to detect the maliciousness of the collected data, we pre-processed the data with Python libraries NumPy (version 1.8.2) and Pandas (version 1.0.2). Then, the TL model is built with Keras (version 2.5.0), Tensorflow, and the Adapt library, whereas the results are plotted with the Matplotlib library version 3.5.3 and the Seaborn library. In the encoder network, there are two layers, and the relu activation function is used in both layers. In the discriminator network, the relu activation function is used in the first layer, followed by the sigmoid function in the next layer. In the task classifier network, the relu activation function is used in the first layer, followed by the softmax layer. In all three networks, the Adam optimizer is used to set the required learning rate to optimize performance. A hyperparameter called lambda is employed in the proposed DA model. The relative significance of the domain loss in comparison to the task loss is determined by lambda. When lambda is larger, the domain loss is given more weightage, which signifies that the model focuses more on minimizing the gap between the respective domains. A lower value of lambda, on the other hand, signifies that the model is more focused on the current task and gives greater weightage to the task loss. In the proposed scheme, it is frequently set via hyperparameter tuning by experimenting with various values. The ethereum SC is written and deployed in Remix IDE (version 0.9.4). Here, one-week Ether and gas prices are used to calculate the storage cost of data in the proposed scheme. These prices are taken from \(18^{th}\) January 2023 to \(24^{th}\) January 2023 to perform simulations28.

The network traces of the ToN-IoT dataset is used to train adversarial model. In the network dataset, each data sample has 44 features. These features contain details for HTTP, SSL, violations, DNS, statistics, and connections. For this study, the network dataset of the ToN-IoT is further splitted into eight subsets, as shown in Table 3, to conduct the different trails for known/unknown threat detection. The threats on which the model is being trained fall under the heading of known threats. The model becomes unaware of the threats for which it has not been trained. Three different scenarios are used in the experiments. For the first testing scenario, the classifier is trained on the dataset with 20,000 samples for each type of DoS and DDoS attacks, with 40,000 normal samples. The learning model is trained on two threats, namely dos and ddos, and tested for the remaining seven attack categories, which includes various attack categories, including injection, XSS, ransomware, scanning, mitm, and backdoor, with roughly 20,000 samples in each category. Eight trials are carried out in this pattern. In terms of known and unknown threats, the training to testing ratio is 2:7.

The learning model in the second scenario is tested for the remaining five attack categories after being trained on the four threats i.e., dos, ddos, mitm, and backdoor in the second scenario. The training to testing ratio for the second case is 4:5. For the third scenario, the model is tested for the remaining three attack types after being trained on six threats, including dos, ddos, mitm, backdoors, passwords, and injection. In this scenario, it is tested on threats, including, xss, ransomware, and scanning. The training to testing ratio for the third scenario is 6:3.

Detection of known/unknown threats with ML classifier

We use the confusion matrix along with several other performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and f1-score, to assess the effectiveness of fundamental ML classifiers like ANN, SVM, etc., across the domains of different threat distribution. The classifier accurately predicts all of the benign/normal data samples as evidenced by all tests in the first scenario achieving 100 percent precision for detecting known and new threat variants. This suggests that there are no false positives in the model. On the other hand, lower f1-scores in the range of 56 to 71 percent demonstrate the model’s incapacity to correctly classify the adversarial data samples that aren’t yet learned/seen. Extensive testing on the Ton-IoT network dataset has proven that learning classifiers like SVM can detect known threats with over 100 percent f1-score and recall. However, accuracy drops to 39.4 percent for identifying unseen threat variants (XSS in this case), as shown in Table 4, and it considerably underperforms for the first testing scenario. However, in the remaining testing trails, the model likewise performs poorly for unidentified threats, with the accuracy falling to 41.95 percent in the second scenario and 61.4 percent in the third scenario. Nonetheless, it is noted that the model excels for even the unidentified threats in the third scenario, where the training to testing ratio is 6:3. Table 5 demonstrates the model’s performance under the three different cases25.

Figure 8 presents the confusion matrix for detecting known learned threats25. Except for one data sample that was incorrectly labelled as anomalous, all of the normal data points are appropriately classed as normal. A total of 8062 of the anomalous data are correctly classified as adversarial, while only 3 are considered to be normal. Figure 9 presents the confusion matrix for detecting unknown threat variants, where 11514 attack data points are incorrectly categorised as normal. The ROC curve for both known and unknown threats is depicted in Fig. 1025. The curve for known threats is symbolized by the orange dot, which shows a true positive rate of 100 percent and zero false positives. The curve for unknown threat variations is symbolized by the green dot, which also shows a high false-positive rate of 100 percent while maintaining a 100 percent true positive rate. The performance of popular ML classifiers, including SVM, ANN, DT, and KNN, over various threat types is shown in Fig. 11. When tested with data (ToN IoT-1) that shares the identical distribution as of the training dataset, i.e., known threats, it is found that these classifiers function effectively. The accuracy falls from 98 to about 39 percent for the varied distribution, termed as unknown threats (ToN IoT-2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). So, for threats with different distributions from the distribution of the training set, the fundamental ML models underperform25.

Detection of unknown threats with TraVel scheme

In this section, we comprehensively evaluate the performance of the TraVel scheme based on fundamental learning parameters. Additionally, we compare the proposed scheme with various machine learning classifiers, including Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Decision Trees (DT). The evaluation includes the computation of the confusion matrix as well as multiple performance metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, AUC (Area Under the Curve) score, and ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve. The performance of the TraVel scheme is specifically assessed under two different testing conditions, referred to as Scenario-1 and Scenario-3, as discussed above. Furthermore, Fig. 12 presents a bar graph comparing the accuracy of the TraVel scheme to that of other ML classifiers (ANN, SVM, KNN, DT) under Scenario-1, illustrating TraVel’s relative effectiveness in detecting threats. The ROC curve for all these threats for Scenario-1 is depicted in Fig. 13. Furthermore, Fig. 14 presents the confusion metrics for detecting unknown threats using TraVel, forming the target space of attacks of mitm, XSS, backdoor, scanning, injection, backdoor, ransomware, and password for Scenario-1 with dos and ddos in source space. The value of other parameters like accuracy, precision, recall, f1-score, AUC score, and loss for Scenario-1 are shown in Table 6, providing a detailed view of each classifier’s performance across multiple dimensions. Figure 15 shows the ROC curves for these attacks, providing insight into the true positive and false positive rates across different detection thresholds for Scenario-3. Figure 16 presents the confusion metrics for detecting unknown threats using TraVel, forming the target space of attacks of XSS, scanning, and ransomware, for Scenario-3 with all the remaining attacks forming the source space. The relative comparison of the proposed TraVel scheme with ML classifiers in terms of accuracy for Scenario-3 is shown as bar graph in Fig. 17. The value of other parameters like accuracy, precision, recall, f1-score, AUC score, and loss for Scenario-3 are shown in Table 7. By training and testing the proposed model on different number of threats, it is found that the model outperforms in Scenario-3, where it is trained on more number of threats. The results demonstrate the superior adaptability of TraVel to dynamic threat landscapes, highlighting its effectiveness in maintaining data integrity and security in IoT environments where threat patterns may frequently change.

Smart contract interface of TraVel

Figure 18 shows the SC interface of the proposed TraVel scheme. Remix IDE is used to write and debug Ethereum SC in the solidity language. When we start Remix, it creates 10 Ethereum accounts, each account with 100 ethers running on a private BC. After writing, it is compiled and deployed on a private BC running in Remix IDE. On compilation, solidity compiler provides us with the bytecode and ABI. To deploy the SC, we store the bytecode of the SC on BC to which Remix associates an address called the deployment address of the SC. The deployment address is used to transfer the virtual ethers to the SC for the required transaction. And ABI provides an interface for an application/SC written in other languages to interact with the deployed SC in the form of bytecode. With Remix testing interface, we have also checked the security vulnerabilities of designed SC, as once we deploy the SC on BC, it can not be modified further in future. Figure 19 shows the attributes, mappings, functions, events, and modifiers defined in the proposed SC.

SC gas profiler

To deploy the smart contracts of TraVel over the BC, the end users must pay a fee to transact and use the smart contracts’ functions. This expense is used for network consensus incentives as well as computation by the EVM. Execution costs are basically the expenses of running a virtual machine, whereas transaction costs are the deployment costs for transferring the contract code to the BC. Transaction costs are dependent on the size of the contract. Every transaction has to pay for the decentralised computing and changing the state of the blockchain. Each function’s transaction in SC is simulated in a testing environment and then its gas profiling (in Gas units) is done using the Gas Profiler in Remix IDE27. To further visualise gas usage, these attributes are plotted. Figure 20 illustrates these transaction and execution costs incurred in the blockchain to carry out each function in terms of gas units. For this, the SC’s functions are executed independently in a local BC, and their cost is calculated and further plotted. This simulation result enables us to calculate the cost of using and communicating with TraVel after deployment. Additionally, the deployment cost of TraVel’s proposed SC after deploying on the simulated blockchain in Remix IDE,is given in the transaction history. Figure 21 depicts the TraVel’s SC deployment cost in Gwei and USDs. The deployment contract comprises the cost of creating SC, contract storage, and its execution with respect to present value of gas in gwei.

IPFS storage cost

In TraVel, the data is stored in two ways, i.e., on-chain and off-chain storage. The on-chain storage is on the blockchain itself and thus, only crucial information like keys, hashes that requires less storage and needs to be kept safe are stored in it. In the latter, data is not stored in the BC, rather stored in decentralized system of IPFS because of high storage cost. Figure 22 depicts the network bandwidth using IPFS simulation for storing the off-chain data in TraVel. Figure 23 shows the storage cost for storing the off-chain data in TraVel in comparison to traditional approaches. In the graph, the y-axis depicts the cost of storing data in USD corresponding to the x-axis that depicts the number of words. The graph shows that the proposed TraVel scheme outperforms the traditional data storage methods as it requires less cost to store data in IPFS. In Ethereum BC, to store one word of size 256 bits it costs 20,000 Gas.29

-

\(1word = 20{,}000Gas\)

-

\(1KB = (2^{10})/(2^5) words\)

-

\(1KB = (2^{10})/(2^5) \times 20{,}000Gas\)

The gas price i.e., \(Gas_{pr}\) (Gwei) and the ether price i.e., \(ET_{price}\) (USD) are dynamic in nature.

And the total cost to store Y words in ethereum BC in USD is calculated as below.

By employing IPFS in TraVel for \(SH_m\) data storage, we only store hashes in BC.

Logs

In TraVel scheme, the internal execution of SC can be viewed through events and logs. The arguments are recorded in the transaction’s log whenever we emit an event. Figure 24 illustrates the logs in remix IDE depicting the addition of the IoT node and self check. When the SC executes the functions for registering node/user,it checks the owner of the function. It triggers a violation when the caller of the function is non-owner. Figure 25 show the logs of triggering a violation of registering node/user by non-owner of SC and denying access to the unauthorized user. Figures 26 and 27 depicts the logs for adding and retrieving IPFS hash from the BC. Figure 28 present the logs showing the access denied to BC for storage as data feeds are malicious.

Network metrics

Scalability

The proposed TraVel scheme illustrates the improved scalability based on the number of blocks mined and transaction time. Thus, it refers to the network’s ability to handle increasing numbers of transactions and users without compromising performance. In TraVel scheme, more transactions can be uploaded to the BC network in a given period of time. Thus, by providing services to additional users, this increases the system’s overall scalability. Further, all the \(SH_m\) data feeds are uploaded to the IPFS storage, only IPFS generated hashes for uploaded data feeds are stored in BC. The size of IPFS hash key is 256 bits < the actual data feeds, which is in kilobytes. This empowers the TraVel scheme to upload more data feeds on BC, consequently improving the scalability.

Latency

The network latency demonstrates how prompt the overall system is in relation to the continual data exchange that occurs in \(SH_m\), i.e., it represents the delay in the communication. Thus, the time delay between sending a request and receiving a response, which is critical for determining how quickly transactions can be confirmed. In conventional schemes, LTE-Advanced serves as the communication network, whereas the proposed TraVel scheme employs 5G network to reduce the delay. Thus, the TraVel performs better than any other existing schemes with minimal latency. This is because the communication delay in LTE and 5G networks, which is \(\le\) 10 ms and < 1 ms respectively, with 99.9999 % of reliability. Additionally, \(SH_m\) transactions need to be handled in real-time. To handle this more efficiently, we employed IPFS in the TraVel scheme, as fetching the solitary transaction from IPFS is more quicker than Ethereum BC, because of its internal DAG structure.

Packet loss

The packet loss rate refers to the percentage of packets that the destination was unable to receive, including packets that were dropped, lost during transmission, and packets that had the incorrect IP address. While connecting to the web or on the Internet, the data is sent and received in the form of small data units called packets. The packet loss occurs even if one of the packets fails to reach its specified destination. The proposed TraVel scheme with a 5G network has the least packet loss for the increasing data traffic. This is because the 4G LTE-A network has a data transfer rate of 20 Mbps with a delay of < 50 milliseconds. On the contrary, 5G reduces the delay to < 1 millisecond.

Conclusion

Smart homes have become one of the most adaptable structures in the IoT landscape, driving the need for a reliable data dissemination scheme to ensure security and privacy. Currently, \(SH_m\) systems are vulnerable to various security breaches. To address this, we propose TraVel, a dissemination scheme based on transfer learning (TL) and blockchain (BC) technology, designed to ensure data privacy and integrity. The TraVel framework operates in two stages. In the first stage, it assesses the integrity of incoming data from SHm devices by using a TL-based classifier, which is trained to detect both known and unknown threats. The second stage manages data storage on the blockchain and enforces access control through smart contracts (SC). In this stage, all IoT devices and users are registered on the SC, which records the status of data feeds from each \(SH_m\) IoT device. When data feeds are classified as non-malicious, the administrator uploads the data files to the IPFS (InterPlanetary File System) and stores their unique hashes. The SC then authenticates these data feeds and devices, storing the hashes of verified non-malicious data on the blockchain. We evaluated the effectiveness of TraVel by comparing it to existing solutions on parameters such as data storage cost, scalability, latency, accuracy, true positive rate, false positive rate, and bandwidth.

Future efforts will focus on implementing TraVel in real \(SH_m\) environments to validate its performance under practical conditions. Further research could also explore optimizing the scheme for broader IoT applications and enhancing its resistance to advanced adversarial attacks. Additionally, incorporating comparative performance evaluations across a wider range of blockchain platforms will provide deeper insights into its scalability and adaptability. These directions will help refine TraVel and expand its applicability to diverse, high-security IoT ecosystems.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the “TON-IOT” datasets and are available in the UNSW Research repository https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/toniot-datasets.

References

Amaral, L. A. et al. Ecloudrfid—a mobile software framework architecture for pervasive RFID-based applications. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 34, 972–979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2010.04.005 (2011). RFID Technology, Systems, and Applications.

Future of industry ecosystems: Shared data and insights. https://blogs.idc.com/2021/01/06/future-of-industry-ecosystems-shared-data-and-insights/. Accessed: 2023.

Hasan, K. et al. A blockchain-based secure data-sharing framework for software defined wireless body area networks. Comput. Netw. 211, 109004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comnet.2022.109004 (2022).

Yang, L., Zou, W., Wang, J. & Tang, Z. Edgeshare: A blockchain-based edge data-sharing framework for industrial internet of things. Neurocomputing 485, 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2021.01.147 (2022).

Miao, Q., Lin, H., Hu, J. & Wang, X. An intelligent and privacy-enhanced data sharing strategy for blockchain-empowered internet of things. Digital Commun. Netw. 8, 636–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcan.2021.12.007 (2022).

Hasan, H. R. et al. Trustworthy IoT data streaming using blockchain and IPFS. IEEE Access 10, 17707–17721. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3149312 (2022).

Singh, P., Masud, M., Hossain, M. S. & Kaur, A. Cross-domain secure data sharing using blockchain for industrial IoT. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 156, 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpdc.2021.05.007 (2021).

Manogaran, G., Alazab, M., Shakeel, P. M. & Hsu, C.-H. Blockchain assisted secure data sharing model for internet of things based smart industries. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 71, 348–358. https://doi.org/10.1109/TR.2020.3047833 (2022).

Pranto, T. H., Noman, A. A., Mahmud, A. & Haque, A. B. Blockchain and smart contract for IoT enabled smart agriculture. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 7, e407. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.407 (2021).

Gupta, R., Patel, M. M., Tanwar, S., Kumar, N. & Zeadally, S. Blockchain-based data dissemination scheme for 5g-enabled softwarized UAV networks. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 5, 1712–1721. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGCN.2021.3111529 (2021).

Khan, M. A. et al. A machine learning approach for blockchain-based smart home networks security. IEEE Netw. 35, 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1109/MNET.011.2000514 (2021).

Aggarwal, S., Shojafar, M., Kumar, N. & Conti, M. A new secure data dissemination model in internet of drones. In ICC 2019—2019 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC.2019.8761372 (2019).

Tanwar, S. et al. Machine learning adoption in blockchain-based smart applications: The challenges, and a way forward. IEEE Access 8, 474–488. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2961372 (2020).

Bagga, P., Das, A. K., Chamola, V. & Guizani, M. Blockchain-envisioned access control for internet of things applications: A comprehensive survey and future directions. Telecommun. Syst., 1–49 (2022).

Mistry, I., Tanwar, S., Tyagi, S. & Kumar, N. Blockchain for 5G-enabled IoT for industrial automation: A systematic review, solutions, and challenges. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 135, 106382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2019.106382 (2020).

Nizamuddin, N., Salah, K., Ajmal Azad, M., Arshad, J. & Rehman, M. Decentralized document version control using ethereum blockchain and IPFS. Comput. Electr. Eng. 76, 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2019.03.014 (2019).

Kumar, S., Bharti, A. K. & Amin, R. Decentralized secure storage of medical records using blockchain and IPFS: A comparative analysis with future directions. Secur. Privacy 4, e162 (2021).

Kurt Peker, Y., Rodriguez, X., Ericsson, J., Lee, S. J. & Perez, A. J. A cost analysis of internet of things sensor data storage on blockchain via smart contracts. Electronics 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9020244 (2020).

Kostamis, P., Sendros, A. & Efraimidis, P. S. Exploring ethereum’s data stores: A cost and performance comparison. CoRR. arXiv:abs/2105.10520 (2021).

Gupta, R., Shukla, A. & Tanwar, S. Bats: A blockchain and AI-empowered drone-assisted telesurgery system towards 6G. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 8, 2958–2967. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSE.2020.3043262 (2021).

Steichen, M., Fiz, B., Norvill, R., Shbair, W. & State, R. Blockchain-based, decentralized access control for IPFS. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData), 1499–1506. https://doi.org/10.1109/Cybermatics_2018.2018.00253 (2018).

Yang, Q., Zhang, Y., Dai, W. & Pan, S. J. Transfer Learning (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Deng, L. The MNIST database of handwritten digit images for machine learning research [best of the web]. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 29, 141–142 (2012).

Ganin, Y. et al. Domain-adversarial training of neural networks. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 17, 2096–2130 (2016).

Anand, P., Singh, Y., Singh, H., Alshehri, M. D. & Tanwar, S. Salt: transfer learning-based threat model for attack detection in smart home. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–19 (2022).

Anand, P. et al. IoT vulnerability assessment for sustainable computing: Threats, current solutions, and open challenges. IEEE Access 8, 168825–168853. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3022842 (2020).

Reebadiya, D., Rathod, T., Gupta, R., Tanwar, S. & Kumar, N. Blockchain-based secure and intelligent sensing scheme for autonomous vehicles activity tracking beyond 5G networks. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 14, 2757–2774 (2021).

The ethereum blockchain explorer. https://etherscan.io/. Accessed: 2023.

Wood, G. et al. Ethereum: A secure decentralised generalised transaction ledger. Ethereum Project Yellow Paper 151, 1–32 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number (TURSP-2020/126), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A., Y.S., H.S.; Data curation, H.S.; Formal analysis, P.A., and Y.S.; Methodology, P.A., H.S., and Y.S.; Domain knowledge, Y.S., and H.S.; Resources, P.A.; Software, H.S., and Y.S.; Validation, P.A., H.S., and Y.S.; Writing-original draft, P.A. and H.S.; Writing-review and editing, Y.S., and P.A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anand, P., Singh, Y. & Singh, H. Secure IoT data dissemination with blockchain and transfer learning techniques. Sci Rep 15, 1665 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84837-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84837-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A privacy preserving intrusion detection framework for IIoT in 6G networks using homomorphic encryption and graph neural networks

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Enhancing secure IoT data sharing through dynamic Q-learning and blockchain at the edge

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A Privacy-Preserving Blockchain Learning Model for Reliable Industrial Internet of Things Data Transmission

SN Computer Science (2025)