Abstract

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) omission improves quality of life but is only considered under certain conditions. We investigated expanding these conditions in patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for clinical N2–3, pathological N0 breast cancer. We retrospectively reviewed data of 1346 patients with clinical N2–3, M0, who underwent surgical resection (sentinel lymph node biopsy [SLNB] only, or level I–II ALND with/without SLNB) following NAC from January 2008 to December 2021. Univariate and multivariate analyses of overall (OS), disease-free (DFS), regional recurrence-free (RFS), and axillary recurrence-free survival (ARFS) were performed before and after propensity score matching (PSM) to control for confounding factors. Of the total patients, 521 (37.5%) achieved an axillary pathological complete response (ypN0). Of these, 293 (56.2%) underwent SLNB only. The median OS was 52.7 months. After PSM, SLNB-only and ALND groups showed no significant differences in ARFS (long-rank p = 0.765), RFS (long-rank p = 0.764), DFS (long-rank p = 0.186), and OS (long-rank p = 0.760). The 5-year ARFS (97.3 vs. 96.7%) and OS (97.7 vs. 97.3%) of both groups did not differ significantly. ALND omission after NAC in clinical N2-3, pathological N0 patients was not inferior to ALND,. Clinical N2-3 patients achieving ypN0 following NAC may be safely treated with SLNB alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, axillary management is shifting towards de-escalation. With the recent improvements of chemotherapeutic agents, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) is expanding1; radiotherapy has also improved lymph node irradiation. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, postoperative breast/chest wall and regional nodal irradiation is recommended for cases of internal mammary and supraclavicular lymph node metastasis where surgical removal is not performed2,3.

The ACOSOG Z0011 trial demonstrated that axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is unnecessary in patients with early breast cancer and one or two sentinel lymph node metastases as they receive whole breast radiation as part of breast-conserving surgery4. Furthermore, omission of ALND after NAC in patients with node-positive breast cancer has been studied in three prospective trials: the ACOSOG Z1071, SENTInel NeoAdjuvant (SENTINA), and Sentinel Node Biopsy Following Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy (SN FNAC) studies5,6,7; these patients became clinically node-negative after receiving NAC and undergoing SLNB alone or ALND (level I–II ALND with or without SLNB). Most importantly, these studies suggest that SLNB is feasible in patients whose disease was converted to clinically node-negative following NAC, and that technical aspects—such as retrieving three or more SLNs, using dual-agent lymphatic mapping with radiotracers and blue dye, and marking with a clip before NAC—lowered false negative rates to < 10%8.

Since the publication of these trials, the administration of SLNB alone to patients with clinically node-positive disease after NAC has increased9. However, surgeons in particular require a rationale to omit ALND for patients with axillary metastasis and no radiologically detected ALN enlargement or conversion to negative-node status after administering post-NAC SLNB10. Most published data has focused on clinical N0-1 breast cancer. Thus, to provide a broader perspective, we examined clinical N2-3 breast cancer. We analyzed patient data from our practice and compared recurrence and survival outcomes between SLNB-only and ALND groups.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the data of 1346 patients who were diagnosed with clinical N2-3, M0 breast cancer and underwent NAC followed by surgical resection between January 2008 and December 2021 at the Asan Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea. Clinical node-positive (cN2-3) disease was defined by fine needle aspiration or axillary core-needle biopsy before the initiation of NAC. We excluded patients with bilateral breast cancer, inflammatory breast cancer, M1 status at the time of initial diagnosis, and cancer other than breast cancer. Among the 521 patients who achieved an axillary pathological complete response (ypN0), 212 and 135 patients had internal mammary and supraclavicular lymph node metastases, respectively. In the final pathology, one case demonstrated the presence of isolated tumor cells (ITCs) [ypN0(i+)], which was considered a nodal pathological complete response (pCR) because there was no difference in medical treatment compared to ypN0. The patient characteristics assessed included age, TNM stage before NAC, histologic grading, nuclear grading, estrogen receptor (ER) status, progesterone receptor (PR) status, HER2 status, Ki67 proliferative index percentage, type of axillary and breast surgery, and adjuvant treatment. We analyzed axillary recurrence-free survival (ARFS), regional recurrence-free survival (RFS), disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS). ARFS was defined as the time to ipsilateral axillary recurrence from initial surgery, RFS was defined as the interval from surgery to recurrence, DFS was defined as the time to disease recurrence or metastasis after surgery, and OS was defined as the time from surgery to death due to any cause. Cancer staging was conducted according to the criteria described in the American joint committee on cancer (AJCC) 8th edition11. In particular, cN2 was defined as ipsilateral level I–II axillary lymph nodes that were clinically fixed or matted, or ipsilateral internal mammary nodes in the absence of axillary lymph node metastases; cN3 was defined as ipsilateral infraclavicular (level III axillary) lymph node(s) with or without level I–II axillary lymph node involvement, ipsilateral internal mammary lymph node(s) with level I–II axillary lymph node metastases, or metastases in ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph node(s) with or without axillary or internal mammary lymph node involvement. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Treatment

Standard regimens were selected based on the clinical stage of patients, and NAC was administered every 3 weeks. Patients with HER2-positive disease received trastuzumab-based chemotherapy before surgery and completed trastuzumab after surgery without other chemotherapy.

We used 99mTc-sulfur colloid as the radiopharmaceutical agent with gamma probe detection to identify SLNs. Additionally, clinically enlarged, palpable ALNs without intense radioactive signals were also excised along with SLNs and included in the overall SLNB count. Although the surgeons’ criteria for proceeding to perform ALND are not always consistent, SLNB was performed in patients who responded well to NAC, as determined by the attending surgeon.

After surgery, each patient received standard treatment—including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and endocrine therapy—either alone or in combination. Adjuvant radiotherapy was administered to patients with clinical or pathological stage 3 disease regardless of their axillary nodal status after surgery. Both groups received regional nodal irradiation from the level 1 axilla to supraclavicular area, regardless of the level of ALND performed.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint was defined as the time to the first event of disease recurrence, including invasive and noninvasive recurrence. The secondary endpoint was ARFS defined as the time from the date of surgery to the date when an initial ipsilateral axillary node recurrence was reported, which was proven radiologically or pathologically. RFS was defined as the time from the date of surgery to the date of recurrence at the ipsilateral axillary, supraclavicular, or internal mammary lymph nodes.

The independent t-test was utilized to compare continuous variables, and the Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test were performed to compare clinicopathologic factors. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to generate survival plots, and the statistical significance of the survival differences among selected factors was verified by conducting the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was applied to univariate and multivariate analyses to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To minimize the potential bias between subgroups, we stratified patients’ data via propensity score matching (PSM) between the SLNB-only and ALND groups based on age, breast surgery, clinical T stage, clinical N stage, tumor grade, molecular subtype, and Ki-67 index. There were 228 and 293 patients in SLNB-only and ALND groups, respectively. After 1:1 matching, there were 200 pairs. We performed statistical analysis under unadjusted and matched conditions. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics 24.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA); the threshold of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The study identified 1,346 patients who met the inclusion criteria. Among these patients, 521 patients achieved ypN0 after NAC and surgery, whereas the others did not. The baseline characteristics prior to NAC are listed in (Table 1). Of the 521 patients, 293 (56.2%) and 228 (43.8%) were in the SLNB-only and ALND groups. After PSM, 200 pairs were matched for each group.

The mean age of all enrolled patients was 50 years. The clinical T2 stage was the most abundant T stage and was observed in 266 (51.1%) patients. In terms of clinical N stage, there were more patients with clinical N3 cancer (347 patients, 66.6%) compared to N2 (174 patients, 33.4%). Breaking this down further, 26 (6.5%) were classified as cN2a, one (0.3%) as cN2b, 92 (23%) as cN3a, and 13 (3.3%) as cN3b.

Regarding the molecular subtypes, the number of ER-negative patients (303 [58.2%]) was higher than ER-positive patients (218 [41.8%]). Additionally, 415 (79.7%) were PR-negative, while 106 (20.3%) patients were PR-positive. HER2-positive breast cancer was 271 patients (52.0%), slightly more than the 250 patients (48.0%) with HER2-negative disease. For the Ki-67 index, the majority had a value of > 20% (505 patients, 96.9%), while only 16 (3.1%) patients had a Ki-67 index < 20%.

Regarding breast surgery types, 276 (53.0%) underwent total mastectomy, and 245 (47.0%) had breast-conserving surgery. In the ALND group 135 (59.2%) underwent total mastectomy, compared to 93 (40.8%) who had breast conserving surgery.

Most patients 493 (94.6%) received radiotherapy. Specifically, 271 patients in the SLNB-only group and 222 patients in the ALND group received radiotherapy. Hormone therapy was administered to 225 patients of total patients, with 135 patients in the SLNB-only group and 90 patients in the ALND group receiving it.

Before PSM, the SLNB-only group exhibited favorable clinical T stages and hormonal receptor statuses, which may have led to differences in the breast surgery type selected (total mastectomy [59.2%] vs. breast-conserving surgery [48.1%]; p = 0.012). After PSM, these differences—which may have confounded the results—were adjusted.

Characteristics of patients with ypN0 after NAC

Table 2 shows the changes in the patient characteristics following NAC administration. After PSM, 113 (56.5%) and 117 (58.5%) patients achieved a pCR in the SLNB-only and ALND groups, respectively. Additionally, the total numbers of removed sentinel lymph nodes with standard deviations were 3.7 ± 1.7 and 1.9 ± 2.0 in the SLNB-only and ALND groups, respectively. After PSM, no significant differences in the achievement of a pCR, hormonal receptor status, HER2 status, Ki-67 index, and postoperative therapy were observed between the SLNB-only and ALND groups.

Survival outcomes

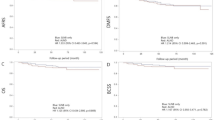

The median follow-up period was 52.7 (range 0–157) months. We analyzed the 5-year survival probability using the Kaplan–Meier method. The survival curves shown in Figs. 1 and 2 were plotted before and after PSM, respectively. Before PSM, there were no differences between the ARFS (log-rank p = 0.584), RFS (log-rank p = 0.720), DFS (log-rank p = 0.091), or OS (log-rank p = 0.350; Fig. 1) of the SLNB-only and ALND groups. Likewise, after PSM, there were no differences between the ARFS (log-rank p = 0.765), RFS (log-rank p = 0.764), DFS (log-rank p = 0.186), or OS (log-rank p = 0.760; Fig. 2) of both groups. After PSM, the ARFSs of the SLNB-only and ALND groups were 97.3% and 96.7%, respectively.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves in the sentinel lymph-node biopsy (SLNB)-only and axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) groups before propensity score matching. (a) Axillary recurrence-free survival (ARFS). (b) Regional recurrence-free survival (RFS). (c) Disease-free survival (DFS). (d) Overall survival (OS).

Kaplan–Meier survival curves in the sentinel lymph-node biopsy (SLNB)-only and axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) groups after propensity score matching. (a) Axillary recurrence-free survival (ARFS). (b) Regional recurrence-free survival (RFS). (c) Disease-free survival (DFS). (d) Overall survival (OS).

According to the results of multivariate Cox analysis adjusted for confounders as shown in Table 3, no significant differences were observed regarding the ARFS, RFS, DFS, and OS of the two groups (HR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.28–3.12; HR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.28–3.10; HR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.40–1.23; HR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.51–1.79, respectively) Additionally, we conducted a Cox regression analysis for relevant factors, including factors in (Table 1). The results are shown in (Supplementary Table 1).

We performed a subgroup analysis to determine the effect of a pCR. According to Kaplan–Meier analysis of the pCR subgroup, there were no differences between the ARFS (log-rank p = 0.987), RFS (log-rank p = 0.987), DFS (log-rank p = 0.105), and OS (log-rank p = 0.792) in the SLNB-only and ALND groups (Fig. 3). Similarly, Kaplan–Meier analysis of the non-pCR subgroup revealed no difference between the ARFS (log-rank p = 0.715), RFS (log-rank p = 0.713), DFS (log-rank p = 0.691), and OS (log-rank p = 0.660) of the SLNB-only and ALND groups (Fig. 4).

Kaplan–Meier survival curves in the sentinel lymph-node biopsy (SLNB)-only and axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) groups after propensity score matching. (a) Axillary recurrence-free survival (ARFS). (b) Regional recurrence-free survival (RFS). (c) Disease-free survival (DFS). (d) Overall survival (OS).

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of patients without a pCR in the sentinel lymph-node biopsy (SLNB)-only and axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) groups after propensity score matching. (a) Axillary recurrence-free survival (ARFS). (b) Regional recurrence-free survival (RFS). (c) Disease-free survival (DFS). (d) Overall survival (OS).

Last, we conducted an additional subgroup analysis based on hormone receptor status. No significant differences were observed between the ARFS, RFS, DFS, and OS of the SLNB-only and ALND groups (Supplementary Figs. 1–4 in Online Resource 1).

Discussion

As our aim was to broaden the feasibility of omitting ALND, we focused on patients with clinical N2-3, a group often less highlighted in research concerning ALND omission. We retrospectively reviewed patients who were diagnosed as pathologically N0 after being treated with NAC. Our main finding was that there were no significant differences in ARFS, RFS, DFS, and OS between the SLNB-only and ALND groups.

The NSABP B-51/RTOG 1304 is a randomized phase 3 clinical trial that evaluated regional nodal irradiation (RNI) therapy in patients with clinically positive axillary lymph nodes before NAC, who converted to negative axillary nodes (ypN0) after NAC12. The study enrolled 1,641 patients with lymph node-positive nonmetastatic breast cancer whose lymph nodes were found to be cancer-free after NAC, and who had undergone either mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery. Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to either the “no RNI” or “RNI” arm. The results showed similar outcomes in RFS over 5 years for both arms (n = 1,56, 91.8% for the no RNI arm vs. 92.7% for the RNI arm). This finding suggests that axillary management can be de-escalated in patients with ypN0 after NAC. Based on this finding, our belief was that if no RNI is possible in ypN0, then de-escalating axillary surgery may also be possible.

According to the AJCC 8th classification, cN2 is defined as ipsilateral level I–II axillary lymph nodes that are clinically fixed or matted, or ipsilateral internal mammary nodes in the absence of axillary lymph node metastases; cN3 is defined as ipsilateral infraclavicular (level III axillary) lymph node(s) with or without level I–II axillary lymph node involvement, ipsilateral internal mammary lymph node(s) with level I–II axillary lymph node metastases, or metastases in ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph node(s) with or without axillary or internal mammary lymph node involvement11. We thus divided our approach into two parts: first, the internal mammary and supraclavicular lymph nodes, and second, the axilla. The EORTC 22,922/10,925 trial, with 15-years of follow-up, demonstrated that irradiation of the internal mammary and supraclavicular lymph nodes significantly reduced mortality and recurrence rates13. At our center, we performed irradiation or surgery depending on the surgeon’s preference, followed by irradiation of the internal mammary and supraclavicular lymph nodes; there were no significant differences observed, regardless of surgery (log-rank p = 0.852 in the PSM group for OS, result not shown).

Next, according to the NCCN guidelines, SLNB of the axilla is recommended after conversion to clinically node-negative following NAC. This consideration considers the well-known postoperative side effects of ALND, which include arm lymphedema and shoulder stiffness8. Currently, several studies—including the ACOSOGZ1071, SENTINA, and SN-FNAC studies—have shown that in cases of cN1 and ypN0, results in SLNB-only cases are not inferior to those of ALND4. Considering this, we reviewed other cN stages that became ypN0. Although no multicenter prospective trials were identified, some studies investigated cN3, ypN0. First, Kim et al.8 aimed to investigate the oncological safety of SLNB in patients with ypN0 disease. The study was also a single-center retrospective study with only 223 patients; however, they included patients from all cN stages. The results showed that the 5-year OS and DFS were not inferior in the SLNB-only group. However, there was no description of the detailed status of N2 and N3, such as internal mammary node metastasis or supraclavicular lymph node status. Second, Piltin et al.1 also aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of SLNB versus ALND in patients treated with NAC. They compared the ARFS and RFS of patients with ypN0 and ypN + disease according to the use of SLNB alone or ALND with or without SLNB. Patients with ypN0 in the SLNB-only group demonstrated the best RFS; however, their median follow-up was relatively short at only 34 months. Additionally, the authors mentioned that the surgical management and chemotherapeutic regimens were not standardized at their center, which may have confounded the results.

We also reviewed previous studies that emphasized the importance of selecting SLNB-only candidates. Most studies considered pCR status and subtype to be significant14. Our institution encountered 129 patients (44.0% of the SLNB-only group) who underwent SLNB only according to the surgeon’s preference, and we were able to confirm that SLNB-only was not inferior to ALND by analyzing the ARFS, RFS, DFS, and OS. Similarly, we compared the subgroups of ARFS, RFS, DFS, and OS by hormone receptor and HER2 status in four combinations. Additionally, in a subanalysis based on whether the tumor had a pCR, the same results were obtained in both the and non-pCR groups.

Being a single-center retrospective analysis, our study has its own limitations; nonetheless, we maintained consistency in protocols and operation skills, ensured uniformity in patient recruitment and management, and controlled data quality well. Despite being conducted at a single-center, we had a substantial sample size. We also retrieved an average of 3.7 sentinel lymph nodes in the SLNB-only group to overcome the False Negative Rate (FNR) in NAC. Additionally, as our study was retrospective, we focused on ypN0; however, clinically, the target will be ycN0, meaning that diagnostic tool standardization should precede. SLNB is performed in patients who have a good response to NAC, as determined by the surgeon. However, our study is helpful in actual practice as it shows the long-term results of omitting ALND in patients who respond well to NAC, even patients who are not ycN0. In spite of these efforts to overcome the disadvantages of a retrospective design, the retrospective nature of this study presents inherent limitations that may affect our conclusions. First, patient selection bias may have occurred. Although we attempted to mitigate this bias using propensity score matching (PSM), residual biases may still persist. Second, there is missing data on certain variables, such as patient follow-up details or treatment records. Since many patients received adjuvant therapy at hospitals near their homes, certain details such as the number of treatment cycles; duration and reasons for discontinuation; and the exact treatment period are missing, which could potentially introduce bias. Third, other confounding variables may not have been fully considered, even though we adjusted for known factors. For these reasons, we believe that further prospective studies are needed.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that SLNB only in patients with cN1–3, ypN0 is not inferior to ALND. This suggests the feasibility of omitting ALND in cN1–3 patients who respond well to NAC. Last, we may broaden our focus to include cN2–3 regarding de-escalation axillary surgery in the future; inevitably, randomized controlled trials will be required.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as the personal information of patients must be protected, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Piltin, M. A., Hoskin, T. L., Day, C. N., Davis, J. Jr. & Boughey, J. C. Oncologic outcomes of sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive breast cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 27, 4795–4801. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-08900-0 (2020).

Poortmans, P. M. et al. Internal mammary and medial supraclavicular lymph node chain irradiation in stage I-III breast cancer (EORTC 22922/10925): 15-year results of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21, 1602–1610. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30472-1 (2020).

Network, N. C. C. Breast cancer version 2. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx (2024).

Chun, J. W. et al. Sentinel node biopsy alone for breast cancer patients with residual nodal disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Sci. Rep. 11, 9056. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88442-x (2021).

Boughey, J. C. et al. Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA 310, 1455–1461 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.278932 (2013).

Kuehn, T. et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 14, 609–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70166-9 (2013).

Boileau, J. F. et al. Sentinel node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in biopsy-proven node-positive breast cancer: the SN FNAC study. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 258–264. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2014.55.7827 (2015).

Kim, H. et al. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in breast Cancer patients with pathological complete response in the axillary lymph Node after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J. Breast Cancer 24, 531–541. https://doi.org/10.4048/jbc.2021.24.e48 (2021).

Caudle, A. S. et al. Use of sentinel lymph node dissection after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer at diagnosis: Practice patterns of American society of breast surgeons members. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 24, 2925–2934. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-5958-4 (2017).

Lee, S. B. et al. Sentinel node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer with axillary node metastasis: a survey of clinical practice. Asian J. Surg. 42, 314–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2018.06.004 (2019).

Amin, M. B. et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (Springer International Publishing, 2018).

The ASCO Post Staff. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy may help some patients with breast cancer skip regional nodal irradiation. https://ascopost.com/news/december-2023/neoadjuvant-chemotherapy-may-help-some-patients-with-breast-cancer-skip-regional-nodal-irradiation/ (2023).

Kaidar-Person, O. et al. The association of internal mammary and medial supraclavicular lymph node radiation technique with clinical outcomes: results from the EORTC 22922/10925 randomised trial. Radiother. Oncol. 172, 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2022.05.006 (2022).

Cortazar, P. et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet 384, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62422-8 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant (Elimination of Cancer Project Fund) from the Asan Cancer Institute of Asan Medical Center, Seoul (2022-0282).

Funding

This study was supported by a grant (2022IF0015-1) from the Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SAll authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Ee Jin Kim, Tae-Kyung Yoo, Jisun Kim, Il Yong Chung, Beom Seok Ko, Hee Jeong Kim, Jong Won Lee, Byung Ho Son, and Sae Byul Lee. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Ee Jin Kim, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. We further confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (IRB) of Asan Medical Center (2022−0282). Here is the detail regarding to patient data security: As a retrospective study, there are no anticipated clinical risks. However, since the study involves the use of patients’ medical records, there is a potential risk of exposing personal information. To mitigate this, minimizing such risks by encrypting the data and restricting access. The anonymized information obtained from the study subjects will be securely managed using locked or password-protected devices, ensuring that only the research team has access. Additionally, anonymized data will be encrypted using MS Excel or MS Access encryption features, preventing anyone other than the researchers from storing or viewing the data.

Consent to participate

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, E.J., Yoo, T.K., Kim, J. et al. Feasibility of de-escalating axillary surgery in patients with clinical N2–3, pathological N0 breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Sci Rep 15, 11128 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84841-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84841-y