Abstract

A significant research gap exists in evaluating the prevalence and quality of Chinese videos depicting CP on domestic social media platforms. In contrast to studies that focus on online video content concerning CP on YouTube, CP videos on YouTube are largely inaccessible to average citizens in mainland China. This disparity underscores the need for further investigation into the availability and nature of CP videos specifically on Chinese social media platforms. To assess the reliability and quality of short videos related to cerebral palsy (CP) on Chinese social media platforms. The present cross-sectional study examined 344 videos about CP from popular Chinese social media platforms, including TikTok, Kwai, Weibo, Bilibili, and RED. The analysis of these videos involved a detailed assessment of their sources, content, and characteristics. Additionally, quantitative scoring tools such as journal of the American medical association (JAMA) benchmarks, gobal quality score (GQS), and DISCERN were utilized to evaluate video quality. Furthermore, the potential relationship between video quality and various attributes such as duration, number of likes, and comments was explored and their impact on the quality of information presented in the videos was analyzed. The average duration of the 344 videos was 92.12 s (SD 105.69). CP rehabilitation training videos comprised 45.64% of the total, followed by expert-contributed videos at 40.70%. Mean scores for JAMA, GQS, and DISCERN were 1.62 (SD 0.60), 2.05 (SD 0.99), and 1.26 (SD 1.26) respectively. RED had the lowest average scores. Videos focusing on disease knowledge scored highest on JAMA and GQS scales. Experts achieved significantly higher GQS and DISCERN scores compared to health-related institutions and amateurs. Spearman correlation analysis revealed a strong positive correlation between likes and comments (r = .0.87, P < .0.001). Enhancing the management of medical content is crucial to address the compromised reliability of Chinese online short videos providing information to families of CP patients. Improving content professionalism and accuracy ensures users access genuinely valuable information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) disorders result from non-progressive brain damage during fetal or infant brain development, impacting movement and posture development1,2. Globally, CP has an estimated incidence rate ranging from 0.20 to 0.35%, with approximately 5 million CP patients in China3,4,5,6. CP is one of the major causes of physical disabilities in childhood, leading to diverse types and levels of secondary functional impairments and damage during child development, thereby imposing significant economic and psychological burdens on families7. The current primary treatment approach for CP is rehabilitation training, comprising therapy in hospitals or specialized rehabilitation institutions and home-based rehabilitation training8. Hospital- or institution-based rehabilitation therapy not only results in substantial economic costs but also requires significant human and time resources from families9,10. Owing to disparities in regional development in China, most remote areas lack the essential medical infrastructure to cater to the basic rehabilitation needs of CP patients11,12. Thus, identifying a reliable and convenient approach to promote the use of home-based rehabilitation training for families affected by CP is crucial.

The rapid evolution of social media has transformed it into a crucial tool for disseminating knowledge, exchanging information, and sharing opinions among individuals13,14,15. Social media platforms, such as TikTok, Kwai, Weibo, Bilibili, and RED, have emerged as the dominant Chinese social media outlets16,17. The highly interactive nature of social media motivates users to turn to these platforms to obtain medical knowledge and make healthcare decisions18,19,20. However, this growing trend has a downside. Chinese users have demonstrated a strong interest in unconventional remedies, resulting in dishonest medical promoters spreading misleading and inaccurate information21,22.

Consequently, this surge of unreliable content poses potential health risks to consumers. In contrast to studies focusing on online video content regarding CP on YouTube, CP videos on YouTube are mostly inaccessible to average citizens in mainland China23,24,25. This disparity highlights a significant research gap in evaluating the prevalence and quality of Chinese videos depicting CP on domestic social media platforms. This study aims to assess the reliability and quality of Chinese videos related to cerebral palsy on local social media platforms, helping to bridge the gap in this area.

Method

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted without the involvement of clinical data, human specimens, or laboratory animals. All information used in the research was sourced from publicly available videos on Chinese social media platforms, thereby ensuring the protection of personal privacy. As there was no interaction with users, the requirement to obtain informed consent was waived. The study received ethical approval from the ethics committee of Lanzhou University Second Hospital (approval 2023 A-419) and was registered at chictr.org (ChiCTR2300074750).

Data collection

Between August 21, 2023, and August 31, 2023, a search was conducted on various social media platforms, including TikTok (Chinese version: www.douyin.com), Kwai (Chinese version: www.kuaishou.com), Weibo (https://weibo.com), Bilibili (www.bilibili.com), and RED (www.xiaohongshu.com), using the search term “cerebral palsy.” All videos on each platform were ranked, and two independent searchers sequentially viewed them in descending order. The inclusion criteria for evaluation were videos in Chinese featuring primary content relevant to CP. Any discrepancies between the two searchers were resolved through a consensus discussion with a third party.

In our study, we developed and implemented an explicit consensus discussion protocol to address discrepancies in video selection between two researchers. The protocol was structured into four main steps to ensure a systematic approach. Initially, two independent researchers conducted searches on the same social media platform using identical keywords, meticulously recording all results and noting any discrepancies. Following this, each researcher independently screened the videos they found, applying predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. For videos where disagreements arose during the screening process, a review panel was convened. This panel included the original searcher and at least one external domain expert, who collaboratively discussed and determined whether the videos met the study’s requirements. The decision-making process was guided by principles of global consistency, integrity, unbiasedness, validity verification, and time-bound completion, with an emphasis on openness and transparency. This approach ensured that the relevance and quality of the videos were thoroughly evaluated and aligned with the study’s objectives. The roles involved in this process included two professionals responsible for conducting the search and initial filtering, as well as at least one external consultant with expertise in social media analytics or health information dissemination. By formally documenting the entire deliberation process and its conclusions, the team ensured that the final sample was selected in a scientifically rigorous and transparent manner, thereby enhancing the study’s overall reliability and impact.

Furthermore, videos that met the inclusion criteria were subjected to further review. The exclusion criteria were duplicates, advertisements, irrelevant content (keywords that do not mention or relate to cerebral palsy in the content), and videos in languages other than Chinese.

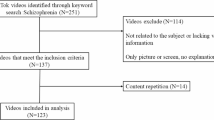

Previous studies that utilized the DISCERN tool for online video research used a Cohen’s effect size of 0.46 for sample size calculation in G*Power 3.126,27. With a power set at 80%, an error tolerance of 0.05, and accounting for potential loss of video segments, a total of 300 videos were determined to be necessary. Subsequently, 60 videos that met the selection criteria were chosen from the top results on various platforms, including TikTok, Kwai, Weibo, Bilibili, and RED. Initially, 500 videos related to CP were obtained from these platforms. After filtering out 48 advertisements, 27 duplicate videos, 69 irrelevant videos, and 12 non-Chinese videos, 344 eligible videos were included in further analysis. The research framework is depicted in (Fig. 1).

Videos categorization

The data were collected separately from the five social media platforms, with each video being assessed for various details such as upload date, video content, video creator’s identity, creator’s attitude, video duration, and interactive behaviors. The video content analysis predominantly centered on four main aspects: providing knowledge on CP, offering guidance on CP rehabilitation training (such as training intensity, frequency, and precautions), showcasing news about CP, and vlogs documenting the daily lives of individuals living with CP. The identities of video creators were categorized as experts, relevant medical institutions, or amateur enthusiasts. Experts included medical professionals, specialists, researchers, and healthcare workers actively engaged in CP research and medical practices. Relevant institutions included hospitals, rehabilitation centers, medical media, and government healthcare organizations. Amateur enthusiasts were defined as individuals lacking relevant medical or research backgrounds. Moreover, interactive behaviors were scrutinized to gauge audience engagement and video popularity, encompassing likes, comments, bookmarks, and shares.

Content analysis of informational videos

The accuracy and reliability of the videos were assessed using the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Benchmarks28 (Table 1). JAMA evaluation criteria, consisting of four standards: authorship, attribution, disclosure, and general information, were applied to evaluate online video content and resources29. Authorship requires videos to include information about authors, contributors, and contact details. Attribution necessitates proper crediting of references and sources. Disclosure involves disclosing relationships with interests, funding, sponsorship, advertising, support, and video ownership. General information calls for the indication of the date of video publication and updates. Each criterion was scored on a point scale. A score of 0 represents low video quality and accuracy, while a score of 4 indicates high video quality and accuracy.

The overall quality of the videos was scored based on the quality and utility of the provided information. The educational value of each video was assessed using the 5-point Global Quality Scale (GQS)30,31 (Table 2). GQS scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating better educational quality. Results were categorized as low quality (1–2 points), moderate quality (3 points), and high quality (4–5 points).

Moreover, to assess the quality and reliability of the health information presented in the videos under consideration, an advanced identification tool, the DISCERN five-point assessment tool, was employed, as elaborated by Kopyigit et al.32. The tool consisted of a series of questions that required a binary response of “yes” or “no,” with one point being awarded for each “yes” answer33,34,35. The total score achieved using this tool is 5 points per the scoring system detailed in (Table 3).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS (version 27.0, IBM Corp). Descriptive statistics were presented as means (standard deviation [SD]). Categorical data were expressed as frequencies and percentages (%). The Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test was employed to analyze non-parametric data among groups. Adjusted P-values were calculated using the Bonferroni method for post-hoc pairwise comparisons to assess the significance among multiple groups. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General information of videos

344 videos published between 2018 and 2023 were obtained from five social media platforms. Most videos (n = 256, 74.42%) were released in 2022 and 2023 (Fig. 2). The average video duration across all platforms was 92.12 s (SD 105.69) (Fig. 3). The descriptive statistical data for videos from various sources and content types are presented in Table 4. Specifically, the search on TikTok yielded 77 videos with 2,234,258 likes, 43,868 comments, 14,248 saves, 18,392 shares, and an average video duration of 90.86 s (SD 90.97). The Kwai search yielded 73 videos with 37,050 likes, 4,641 comments, 5,752 saves, and an average video duration of 70.81 s (SD 81.67). The Weibo search yielded 63 videos with 7,946 likes, 662 comments, 440 shares, and an average video duration of 108.71 s (SD 97.85). The Bilibili search produced 64 videos with 13,462 likes, 430 comments, 2,887 saves, 1,184 shares, and an average video duration of 124.66 s (SD 123.88). The RED search retrieved 67 videos with 5,403 likes, 1,032 comments, 2,700 saves, and an average video duration of 70.12 s (SD 123.78). Notably, analysis of the video sources showed that experts posted 40.70% (140/344) of the videos, while health-related institutions accounted for 32.85% (113/344) and amateurs for 26.45% (91/344) of the content (Figs. 4 and 5). Further analysis of the video content revealed that rehabilitation training was the most prevalent theme, accounting for 45.64% (157/344) of all videos, followed by videos focusing on disease knowledge (24.42%, 84/344), news (9.01%, 31/344), and vlogs (20.93%, 72/344), respectively (Fig. 6).

Video quality assessments

The mean scores of the 344 videos were 1.62 (SD 0.60) for JAMA, 2.05 (SD 0.99) for GQS, and 1.26 (SD 1.26) for DISCERN. JAMA, GQS, and DISCERN scores were also compared across various platforms, sources, and content types (Fig. 7).

JAMA, GQS, and DISCERN scores were analyzed using different platforms, including TikTok, Kwai, Weibo, Bilibili, and RED (Fig. 8). For JAMA scores, the platforms scored as follows: Weibo had the highest score of 1.79 (SD 0.68), followed by TikTok with a score of 1.68 (SD 0.64), Kwai with 1.64 (SD 0.61), Bilibili with 1.59 (SD 0.50), and RED with a score of 1.39 (SD 0.49). Significant differences were observed in JAMA scores among the platforms (H = 14.53, P < .05), with post hoc analyses indicating that RED scored significantly lower than TikTok, Kwai, Weibo, and Bilibili (P < .05). Regarding GQS scores, the platforms scored as follows: TikTok had the highest score of 2.39 (SD 1.07), followed by Weibo with a score of 2.25 (SD 1.02), Bilibili with 2.09 (SD 0.89), Kwai with 1.78 (SD 1.04), and RED with 1.73 (SD 0.73). There were significant differences in GQS scores among the platforms (H = 25.34, P < .001), with post hoc analyses revealing that TikTok, Weibo, and Bilibili had significantly higher scores than Kwai and RED (P < .05). In terms of DISCERN scores, the platforms scored as follows: TikTok had the highest score of 1.71 (SD 1.46), followed by Weibo with a score of 1.62 (SD 1.31), Bilibili with 1.22 (SD 1.09), Kwai with 0.92 (SD 1.18), and RED with 0.79 (SD 0.93). Significant differences existed in DISCERN scores among the platforms (H = 27.25, P < .001), with post hoc analyses indicating that TikTok and Weibo had significantly higher scores than both Kwai and RED (P < .05).

Meanwhile, JAMA, GQS, and DISCERN scores were analyzed across different sources (Fig. 9). Experts, health-related institutions, and amateurs achieved JAMA scores of 1.53 (SD 0.58), 1.61 (SD 0.71), and 1.77 (SD 0.42), respectively. Significant differences in JAMA scores were observed among the three sources (H = 13.35, P < .05). Further analysis through post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction revealed that amateurs received significantly higher JAMA scores than experts and health-related institutions (P < .05). Regarding GQS scores, experts, health-related institutions, and amateurs have attained scores of 2.41 (SD 1.03), 2.03 (SD 0.93), and 1.54 (SD 0.75), respectively. Notably, statistically significant differences in GQS scores were found across the three sources (H = 45.14, P < .001). Subsequent post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction indicated that experts had significantly higher GQS scores than health-related institutions (P < .0.05), and health-related institutions scored significantly higher than amateurs (P < .0.05). For DISCERN scores, the study revealed that experts, health-related institutions, and amateurs obtained scores of 1.71 (SD 1.38), 1.19 (SD 1.16), and 0.63 (SD 0.86), respectively. DISCERN scores significantly differed among the three sources (H = 39.67, P < .0.001). The post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction indicated that experts scored significantly higher in DISCERN than health-related institutions (P < .05), and health-related institutions scored significantly higher than amateurs (P < .0.05).

Subsequently, JAMA, GQS, and DISCERN scores were assessed within different content types, and distinct patterns emerged (Fig. 10). Regarding JAMA scores, disease knowledge, rehabilitation training, news, and vlogs, received ratings of 1.77 (SD 0.59), 1.55 (SD 0.60), 1.74 (SD 0.63), and 1.54 (SD 0.55), respectively. Further statistical analysis revealed significant variations in JAMA scores across different content categories (H = 10.94, P < .05). Post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction highlighted a significant difference, with the JAMA score for disease knowledge significantly surpassing that for rehabilitation training (P < .05). For GQS scores, disease knowledge, rehabilitation training, news, and vlogs received scores of 2.31 (SD 1.09), 2.03 (SD 0.91), 2.00 (SD 1.06), and 1.83 (SD 0.96), respectively. Similarly, significant differences were observed in GQS scores across content categories (H = 8.89, P < .05). Notably, the GQS score for disease knowledge was superior to that for vlogs based on post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction (P < .05). Concerning DISCERN scores, disease knowledge, rehabilitation training, news, and vlogs received ratings of 1.48 (SD 1.31), 1.19 (SD 1.19), 1.48 (SD 1.34), and 1.04 (SD 1.30), respectively. Compared with JAMA and GQS scores, no statistically significant differences in DISCERN scores were observed among the various content categories (H = 6.69, P = .082).

Correlation analysis

The Spearman correlation analysis demonstrated a strong positive correlation between likes and comments (r = .87, P < .001). However, other variables showed either a very weak correlation or no correlation. Specifically, likes exhibited a very weak negative correlation with duration (r = −0.20, P < .001) but showed no statistically significant correlation with JAMA (r = .11, P = .035). Similarly, comments had a weak negative correlation with duration (r = −0.19, P < .001) but exhibited no significant correlation with GQS (r = −0.18, P < .001) or DISCERN (r = −0.16, P = .003). Notably, comments showed a significant positive correlation with JAMA (r = .15, P = .004). These findings are summarized in (Table 5).

Discussion

Nowadays, the utilization of social media for obtaining health-related information has become increasingly common. Therefore, the current study sought to address the paucity of data on the characteristics of Chinese social media content related to children with CP, mainly focusing on social media within mainland China. Furthermore, the study assessed video quality using established tools such as JAMA, GQS, and DISCERN. The potential correlations between video quality and various video features, including duration, likes, and comments, were also explored.

The analysis included 344 social media videos on CP in mainland China, with over 70% published in the last two years. This observation suggests that individuals affected by CP and their families tend to prioritize recent content when seeking information about the condition on social media platforms. The preference for newer content may be attributed to the platforms’ algorithms to promote the content36. User engagement metrics such as likes, comments, saves, and shares serve as indicators of video popularity37,38. Notably, a positive correlation was found between likes and comments, implying that more popular videos are more likely to receive promotion. Among the social media platforms studied, videos posted on TikTok were the most popular. Therefore, in disseminating educational videos concerning CP, emphasis should be placed on leveraging TikTok for content sharing while encouraging audience interaction and periodically refreshing or reposting content every two years.

The consistently low average scores indicate that videos about CP on Chinese social media platforms generally receive lower ratings for information disclosure, overall quality, and reliability. Consequently, the overall performance of these videos can be deemed unsatisfactory. It is vital to highlight the significance of informing patients, their families, and healthcare professionals about the misleading nature of these videos, which may hinder the effectiveness of rehabilitation programs.

Based on observations across the five platforms, RED performed the worst regarding information disclosure, with Kwai and RED receiving the lowest scores in overall quality and the lowest reliability. Meanwhile, the RED platform displayed the poorest performance regarding information disclosure. This deficiency can be attributed to RED’s primary focus as a social platform for sharing personal experiences, where content producers prioritize sharing individual experiences over disseminating professional medical knowledge39,40. Consequently, detailed information regarding CP, professional knowledge during rehabilitation, and the latest research developments on the disease are susceptible to neglect or misinformation within this environment. For overall quality, Kwai and RED also garnered the lowest scores, which may be associated with the user demographics and content production patterns on these platforms. Both Kwai and RED boast a significant user base of young individuals, many of whom lack medical backgrounds or professional training, leading to videos that lack accuracy, professionalism, and content depth30,41,42. Furthermore, content producers on these platforms often prioritize attractiveness and entertainment value over accuracy and scientific rigor, consequently impacting the overall quality of the content21,25. Kwai and RED also demonstrated poor reliability performance. This outcome could be attributed to the platforms’ content review mechanisms and user interaction patterns, suggesting that these platforms lack stringent medical content review mechanisms, thereby allowing the circulation of a substantial amount of inaccurate or misleading information43,44. Moreover, user interactions and comments may exacerbate this issue as non-professional discussions and advice could further misinform the audience45,46.

Further analysis of various sources and content types revealed that information on CP shared by experts was rated the highest in quality and reliability. This underscores the significance of expert opinions in delivering precise and dependable information. Experts are known for their extensive medical knowledge and practical experience, which enables them to provide evidence-based advice and guidance47. Compared with laypersons or non-professionals, experts are more inclined to furnish accurate and comprehensive information to assist families managing CP patients in making well-informed decisions48. Despite the superior quality of information provided by experts, it is noteworthy that their information may be limited in quantity and accessibility. Particularly on social media platforms, the content posted by experts may need more richness and diversity found in posts by ordinary users or non-professionals. This limitation could present challenges for families of individuals with CP accessing relevant and varied information. Hence, along with promoting information sharing by experts, it is imperative to explore alternative strategies to improve the accessibility and diversity of available information.

We found that videos about cerebral palsy on Chinese social media platforms are generally of low quality, which significantly impacts family decision-making. Families often rely on this video content when seeking information and support related to cerebral palsy. However, due to the lack of video quality, families may receive inaccurate or misleading information, which may lead them to make decisions based on misinformation when developing treatment plans and rehabilitation strategies. For example, certain videos may exaggerate the effectiveness of specific treatments while ignoring scientific evidence and professional advice, thus affecting families’ trust and choice of treatment options. Low-quality videos may also hinder the effectiveness of rehabilitation programs as they may provide incomplete or incorrect rehabilitation guidance, leading patients to take inappropriate measures that may not only delay the rehabilitation process but also have negative health consequences. If patients and families rely excessively on such information, they may even ignore the advice of healthcare professionals, further hindering the implementation of a professional rehabilitation program. These consequences highlight the importance of improving the quality of cerebral palsy-related information on social media. To ensure that patients and families have access to accurate health information, there is a need to strengthen platform regulation, improve the professionalism of content creators, and encourage the involvement of medical professionals in content creation and review. Future research should delve deeper into the specific effects of low-quality videos and explore ways to mitigate these problems through education and intervention while taking advantage of social media to improve the public’s ability to recognize high-quality health information.

Several key measures should be implemented to enhance the reliability and accuracy of CP rehabilitation information. Firstly, it is recommended that platforms should collaborate with professional organizations to strengthen the moderation and management of CP rehabilitation information. By establishing user feedback mechanisms, platforms can elevate standards for information disclosure, overall quality, and reliability. These efforts are essential in reducing the dissemination of false or misleading information. Secondly, healthcare professionals and relevant organizations should proactively disseminate accurate and reliable CP rehabilitation information on social media. This approach aims to enhance public awareness and understanding of CP rehabilitation. Finally, governments and relevant organizations should intensify promotional and educational efforts surrounding CP rehabilitation information. Increasing societal attention and support for families with CP patients ensures they have access to accurate and valuable information from reliable sources.

This is the first study to evaluate the quality and reliability of CP-related videos on social media in mainland China using a combination of tools such as JAMA, GQS, and DISCERN. Analysis of the relationship between likes, comments, video duration, and video quality revealed a positive correlation between likes and comments. However, this study has some limitations. The tools employed, namely JAMA, GQS, and DISCERN, are primarily used in the assessment of the quality of medical information and may have constraints when applied to the context of family-based CP rehabilitation49,50. Furthermore, our analysis focused solely on Chinese videos within mainland China, potentially neglecting pertinent videos in other languages, thereby introducing regional and cultural biases to the study outcomes.

Conclusion

Chinese online short videos offer a convenient way for families with CP patients to access information. However, the reliability of these videos poses serious concerns. Therefore, social media platforms should strengthen the review and management of medical content, improve content professionalism and accuracy, and ensure that users can access valuable information while browsing.

Data availability

The study’s original data are included in the article/supplementary material. For further inquiries, please contact the corresponding author.

References

Rosenbaum, P. et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Developmental medicine and child neurology. Supplement 109, 8–14 (2007).

Colver, A., Fairhurst, C. & Pharoah, P. O. Cerebral palsy. Lancet (London England) 383 (9924), 1240–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61835-8 (2014).

Arnaud, C. et al. Public health indicators for cerebral palsy: a European collaborative study of the surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe network. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 37 (5), 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12950 (2023).

Barron-Garza, F. et al. Incidence of cerebral palsy, risk factors, and neuroimaging in Northeast Mexico. Pediatr. Neurol. 143, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2023.02.005 (2023).

Ahmed, A., Rosella, L. C., Oskoui, M., Watson, T. & Yang, S. Prevalence and temporal trends of cerebral palsy in children born from 2002 to 2017 in Ontario, Canada: Population-based cohort study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 65 (2), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15324 (2023).

McIntyre, S. et al. Global prevalence of cerebral palsy: a systematic analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 64 (12), 1494–1506. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15346 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. Corrigendum: effects of melatonin on neurobehavior and cognition in a cerebral palsy model of plppr5-/- mice. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 879685. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.879685 (2022).

Mori, M. et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1α plays a crucial role based on neuroprotective role in neonatal brain injury in rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16 (8), 18018–18032. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160818018 (2015).

Wikström, T. et al. Cost-effectiveness of cervical length screening and progesterone treatment to prevent spontaneous preterm delivery in Sweden. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. Official J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 59 (6), 778–792. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.24884 (2022).

Profit, J. et al. Clinical benefits, costs, and cost-effectiveness of neonatal intensive care in Mexico. PLoS Med. 7 (12), e1000379. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000379 (2010).

Liu, Q. et al. Clinical analysis of pediatric glaucoma in central China. Front. Med. 9, 874369. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.874369 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. Development of a novel nomogram for predicting premature rupture of membrane in pregnant women with vulvovaginal candidiasis. Front. Med. 8, 717978. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.717978 (2021).

Deyu, Z. L. Y., Chen, Zhang & Yulan He. Xuan & Unsupervised event exploration from social text streams. Intell. Data Anal. 21 (4), 849–866. https://doi.org/10.3233/ida-160048 (2017).

Farah, B., Diana, I. & Maite, T. Introduction to the special Issue on language in social media: exploiting discourse and other contextual information. Comput. Linguist. 44 (4), 663–681. https://doi.org/10.1162/coli_a_00333 (2018).

Bouffard, D. G. & Zane, Z. Social Media and romantic relationship: excessive social Media Use leads to relationship conflicts, negative outcomes, and addiction via mediated pathways. Social Sci. Comput. Rev. 40 (6), 1523–1541. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393211013566 (2021).

Jing, Z. & Crystal Abidin. #OkBoomer, time to meet the zoomers’: studying the memefication of intergenerational politics on TikTok. Inform. Commun. Soc. 24 (16), 2459–2481. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2021.1961007 (2021).

Nikfarjam, A., Sarker, A., O’Connor, K., Ginn, R. & Gonzalez, G. Pharmacovigilance from social media: mining adverse drug reaction mentions using sequence labeling with word embedding cluster features. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. JAMIA. 22 (3), 671–681. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocu041 (2015).

Zhong, B., Huang, Y. & Liu, Q. Mental health toll from the coronavirus: social media usage reveals Wuhan residents’ depression and secondary trauma in the COVID-19 outbreak. Comput. Hum. Behav. 114, 106524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106524 (2021).

Helve, O. A medical consultation service on facebook: descriptive analysis of questions answered. J. Med. Internet. Res. 16 (9), e202. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3194 (2014).

Jo, S., Pituch, K. A. & Howe, N. The relationships between social media and human papillomavirus awareness and knowledge: cross-sectional study. JMIR Public. Health Surveil. 8 (9), e37274. https://doi.org/10.2196/37274 (2022).

Liang, J. et al. Quality and audience engagement of takotsubo syndrome-related videos on TikTok: Content analysis. J. Med. Internet. Res. 24 (9), e39360. https://doi.org/10.2196/39360 (2022).

Zhang, X. A. & Cozma, R. Risk sharing on Twitter: social amplification and attenuation of risk in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Hum. Behav. 126, 106983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106983 (2022).

Furtado, M. A. S. et al. Analysis of informative content on cerebral palsy presented in brazilian-portuguese YouTube videos. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 42 (4), 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2022.2046677 (2022).

Shen, C. et al. Using reports of symptoms and diagnoses on social media to predict COVID-19 case counts in mainland China: Observational infoveillance study. J. Med. Internet. Res. 22 (5), e19421. https://doi.org/10.2196/19421 (2020).

Bai, G., Fu, K., Fu, W. & Liu, G. Quality of internet videos related to pediatric urology in mainland China: a cross-sectional study. Front. Public. Health 10, 924748. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.924748 (2022).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39 (2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146 (2007).

Oremule, B., Patel, A., Orekoya, O., Advani, R. & Bondin, D. Quality and reliability of YouTube videos as a source of patient information on rhinoplasty. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 145 (3), 282–283. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2018.3723 (2019).

Mac, O. A., Thayre, A., Tan, S. & Dodd, R. H. Web-based health Information following the renewal of the cervical screening program in Australia: evaluation of readability, understandability, and credibility. J. Med. Internet. Res. 22 (6), e16701. https://doi.org/10.2196/16701 (2020).

Eksi Ozsoy, H. Evaluation of YouTube videos about smile design using the DISCERN tool and journal of the American medical association benchmarks. J. Prosthet. Dent. 125 (1), 151–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2019.12.016 (2021).

Mueller, S. M. et al. Fiction, falsehoods, and few Facts: cross-sectional study on the content-related quality of atopic eczema-related videos on YouTube. J. Med. Internet. Res. 22 (4), e15599. https://doi.org/10.2196/15599 (2020).

Esen, E., Aslan, M., Sonbahar, B. Ç. & Kerimoğlu, R. S. YouTube english videos as a source of information on breast self-examination. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 173 (3), 629–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-5044-z (2019).

Kocyigit, B. F. & Akaltun, M. S. Does YouTube provide high quality information? Assessment of secukinumab videos. Rheumatol. Int. 39 (7), 1263–1268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04322-8 (2019).

Charnock, D., Shepperd, S., Needham, G. & Gann, R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 53 (2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.53.2.105 (1999).

Szmuda, T. et al. YouTube as a source of patient information for coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a content-quality and audience engagement analysis. Rev. Med. Virol. 30 (5), e2132. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2132 (2020).

Memioglu, T. & Ozyasar, M. Analysis of YouTube videos as a source of information for myocarditis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Res. Cardiol. Official J. German Cardiac Soc. 111 (10), 1113–1120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-022-02026-x (2022).

& Ronald Deibert. Three painful truths about social media. J. Democr. 30 (1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0002 (2019).

Ding, X., Feng, P., Wang, J. & Lin, M. Metaphorical or straightforward? Comparing the effectiveness of different types of social media advertising. Front. Neuro Sci. 16, 851729. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.851729 (2022).

Li, K., Zhou, C., Luo, X. R., Benitez, J. & Liao, Q. Impact of information timeliness and richness on public engagement on social media during COVID-19 pandemic: an empirical investigation based on NLP and machine learning. Decis. Support Syst. 162, 113752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2022.113752 (2022).

Yuanhang, L. & Xinjian, L. Pale, Young, and slim girls on red: a study of young femininities on social media in post-socialist China. Fem. Media Stud. 0 (0), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2023.2226830 (2023).

Yixuan, L. & Wei, W. Discipline and resistance in the representation of motherhood: postpartum recovery discussion onXiaohongshu. Fem. Media Stud. 0 (0), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2022.2048047 (2022).

Luo, C., Bian, L., Jiang, L., Liang, W. & Wu, Z. Does YouTube provide qualified patient education videos about atrial fibrillation? Front. Public. Health 10, 925691. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.925691 (2022).

Malik, F. S. et al. Adolescent perspectives on the use of social media to support type 1 diabetes management: Focus groupstudy. J. Med. Internet. Res. 21 (6), e12149. https://doi.org/10.2196/12149 (2019).

Green, B. M. et al. Assessment of adaptive engagement and support model for people with chronic health conditions in online health communities: combined content analysis. J. Med. Internet. Res. 22 (7), e17338. https://doi.org/10.2196/17338 (2020).

Johnson, V. et al. The ‘Fauci effect’: reducing COVID-19 misconceptions and vaccine hesitancy using an authentic multimodal intervention. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 70, 102084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2022.102084 (2022).

Li, P. et al. Cross-verification of COVID-19 information obtained from unofficial social media accounts and associated changes in health behaviors: web-based questionnaire study among Chinese netizens. JMIR Public. Health Surveil. 8 (5), e33577. https://doi.org/10.2196/33577 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Web-based medical information searching by Chinese patients with breast cancer and its influence on survival: Observational study. J. Med. Internet. Res. 22 (4), e16768. https://doi.org/10.2196/16768 (2020).

Mohammed, B., Baghdad, A. & Sofia, B. Diabetes diagnosis by case-based reasoning and fuzzy logic. Int. J. Interact. Multimedia Artif. Intell. 5 (3), 72–72. https://doi.org/10.9781/ijimai.2018.02.001 (2018).

Mouchabac, S., Leray, P., Adrien, V., Gollier-Briant, F. & Bonnot, O. Prevention of suicidal relapses in adolescents with a smartphone application: Bayesian network analysis of a preclinical trial using in silico patient simulations. J. Med. Internet. Res. 23 (9), e24560. https://doi.org/10.2196/24560 (2021).

Ma, M. et al. Evaluation of medical information on male sexual dysfunction on baidu encyclopedia and Wikipedia: comparative study. J. Med. Internet. Res. 24 (8), e37339. https://doi.org/10.2196/37339 (2022).

Mueller, S. M. et al. The absence of evidence is evidence of non-sense: cross-sectional study on the quality of psoriasis-related videos on YouTube and their reception by health seekers. J. Med. Internet. Res. 21 (1), e11935. https://doi.org/10.2196/11935 (2019).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82105021). The funders had no role in the study design, execution, or reporting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author ContributionsThis work was conceived by QX, who contributed to the study design, project management, and fund procurement. Data collection and analysis were performed by WH, DT, and YJ, who also wrote the manuscript. The figures and tables were generated by YK and WZ, while WZ provided guidance on English writing. Literature search was carried out by WH. The manuscript was revised by QX and YJ. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The Research Ethics Committee of the Lanzhou University Second Hospital reviewed and approved(approval 2023 A-419) studies that did not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, W., Tang, D., Jin, Y. et al. Quality of cerebral palsy videos on Chinese social media platforms. Sci Rep 15, 13323 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84845-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84845-8