Abstract

It is crucial to determine the potential subgroups of sleep disturbances in patients undergoing elective surgery based on the importance of symptom clusters and individual characteristics in order to develop targeted symptom management plans. This study explored the potential categories of postoperative sleep disturbances in patients undergoing elective surgery through latent profile analysis, and explored the influencing factors of each category. A total of 400 eligible elective surgery patients were included in the analysis, and three potential subgroups were identified: mild sleep disturbance group (c1 = 140,35.0%), moderate sleep sleep disturbance group (c2 = 177,44.2%), and severe sleep disturbance group (c3 = 83,20.8%). It was found that the higher the BMI, the greater the probability of patients belonging to the moderate sleep disturbance group (OR = 1.114, P = 0.002) and the severe sleep disturbance group (OR = 1.258, P < 0.001),the longer the duration of anesthesia the greater the likelihood of patients belonging to the severe sleep disturbance group (OR = 1.004,P = 0.011), the greater the pain the greater the probability of patients belonging to the moderate sleep disturbance group (OR = 1.590,P < 0.001) and severe sleep disturbance group (OR = 1.785,P < 0.001), and the higher the anxiety level the greater the probability that patients were in the moderate sleep disturbance group (OR = 1.135,P = 0.007) and severe sleep disturbance group (OR = 1.261,P < 0.001).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postoperative Sleep Disturbances (PSD) refer to the abnormal changes in sleep duration and quality experienced by patients following surgical procedures. These disturbances can manifest as reduced sleep duration, decreased sleep quality, and alterations in sleep structure1,2,3,4. Patients may encounter difficulties falling asleep, frequent awakenings during the night, early morning awakenings, fragmented sleep, and disruptions in sleep cycles5,6,7. PSD is a common complication of surgery, with an incidence ranging from 15 to 72%8,9 The occurrence of PSD can adversely impact postoperative recovery and affect cognitive function, emotional well-being, memory, pain perception, cardiovascular outcomes, and metabolic processes.

PSD results from the interplay of multiple factors. Specific conditions following surgery-such as the type of surgical procedure, anesthesia duration, length of surgery, and discomfort caused by postoperative pain and complications-can all influence sleep quality10,11,12. A single-center prospective observational study found that orthopedic surgery, gastrointestinal surgery, ear-nose-throat surgery, and longer surgery duration are significant risk factors for the occurrence of PSD13. Randomized clinical trials investigating PSD in gynecological laparoscopic surgery have shown that preoperative anxiety and depression scores, anesthesia duration, and postoperative pain scores are associated with the incidence of PSD14,15. Researchers have utilized the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) to categorize elderly patients undergoing elective thoracic surgery into groups based on sleep disturbances (a score of ≥ 5 indicates sleep disturbance) and used logistic regression analyses to identify risk factors for PSD. The findings indicated that a history of insomnia, a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 24 kg/m2, comorbid diabetes, open chest surgery, surgery duration of ≥ 120 min, and moderate to severe postoperative pain are risk factors for PSD in elderly thoracic surgery patients16,17,18.

Currently, investigations into the factors influencing PSD often rely on mean and standard deviation values to determine cutoff points, treating the patient population as homogeneous and overlooking the inherent heterogeneity among patients with PSD19,20. This can lead to a lack of personalized intervention strategies for those affected by PSD.

Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) is an individual-centered analytical method that explains and estimates the relationships between latent categorical variables and observed continuous variables21,22. This approach offers a novel perspective for exploring population characteristics and heterogeneity. Therefore, we utilized the statistical tools Mplus version 8.323 and IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.024 to conduct Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) on patients with postoperative sleep disturbances to identify different latent categories and analyze the influencing factors for each category. This will provide a foundation for developing personalized care plans and interventions in clinical practice. Through this method, we aim to effectively improve postoperative patients’ sleep quality and support their overall recovery. Additionally, we hope our findings will contribute to a deeper understanding of the complexity and diversity of postoperative sleep disturbances.

Material and methods

Research shows that the incidence of sleep disturbances within 2 days after surgery can reach over 90%25. On the first day after surgery, incomplete metabolism of anesthetic drugs or the use of analgesic pumps may affect our assessment of postoperative sleep quality. Therefore, we chose to conduct a questionnaire survey on the second day after surgery. This was a cross-sectional survey study. Data were collected from May 2023 to October 2023 at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University in Zunyi City, Guizhou Province, China. According to the sample size calculation formula: n = [u2α/2π(1-π)]/δ2, π = 0.05, and allowable error δ = 0.04, considering a 15% invalid questionnaire rate, a minimum sample size of 390 is required. The final effective sample size for this study is 400, which meets the sample size requirement.

Subjects

Inclusion criteria: ① Patients undergoing elective surgery; ② American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification: grade I toIII; ③ Age: 18 to 80 years; ④ Consciousness and clear in responses; ⑤ No history of mental illness; ⑥ Informed consent. Exclusion criteria: ① Preoperative Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score > 7; ② Neurosurgery or day surgery; ③ History of long-term use of psychotropic drugs; ④ Presence of cognitive or communication disturbances. Exclusion criteria during the survey: ① Postoperative transfer to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU); ② Occurrence of severe cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events.

Measures

Collection of general information

The patients’ age, gender, body mass index (BMI), educational level, smoking history, alcohol history, ASA grade, past medical history, and baseline sleep were collected. Among them, we used the PSQI to assess the patient’s sleep situation one day before surgery. If the PSQI score is greater than 7, indicating the presence of sleep disturbances before surgery, they will not be included in our study.

Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI)

PSQI consists of seven dimensions: sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. Each dimension is scored on a 0–3 scale, with a total score ranging from 0 to 21. Higher scores indicate poorer sleep quality26. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale is 0.842, and at a cutoff score of 7, the sensitivity and specificity of the scale are 98.3% and 90.2% respectively27. In this study, a PSQI score > 7 was used to indicate the presence of sleep disturbances.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)

It is a reliable tool for assessing symptoms of anxiety and depression, consisting of separate anxiety and depression subscales. Each subscale consists of 7 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 3. The total score ranges from 0 to 21. A score of 8 or higher indicates the presence of anxiety or depression symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the overall HADS scale, anxiety subscale, and depression subscale are 0.879, 0.806, and 0.806, respectively. The test–retest reliabilities are 0.945, 0.921, and 0.932 for the overall scale, anxiety subscale, and depression subscale, respectively28.

Numerical rating scale (NRS)

The NRS is recognized as the gold standard for pain assessment by the American Pain Society29. This scale is widely used in clinical settings, where patients self-evaluate their pain on a 10-point scale. A higher score indicates more severe pain. A score of 0 represents no pain, 1–3 represents mild pain, 4–6 represents moderate pain, and 7–10 represents severe pain30.

Data collection methods and quality control

Before starting the survey, we will conduct standardized training for the participants involved to ensure that data collectors use consistent scripts when administering the questionnaires. This approach aims to enhance the consistency and accuracy of the data collection process, minimize potential biases, and ensure that the collected data more accurately reflects the research objectives. After obtaining the consent of the survey subjects, explain the filling method and precautions of the questionnaire to them. Immediately check the completeness and validity of the questionnaire after completion. We distributed a total of 416 questionnaires in this study and received 400 responses, with an effective response rate of 96.2%. The disease-related data in our study will be collected by investigators through the electronic medical record system of the hospital where the research subjects are located.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0. Continuous variables in this study did not follow a normal distribution and were described using the median and interquartile range [M (P25, P75)]. Group comparisons were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical data were described using frequencies and proportions, and group comparisons were conducted using \({x}^{2}\) test or Fisher’s exact test. Multiple logistic regression analysis was employed to explore the influencing factors of postoperative sleep disturbances in elective surgery patients. A two-tailed significance level of α = 0.05 was used, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Build a latent profile classification model using Mplus version 8.3 software, with each dimension score of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) as the manifest variable. Start with a one-class model and gradually increase the number of classes until the model fit indices reach optimal values. Model fit indices include:(1)Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (aBIC). Smaller values indicate better model fit31. (2)Entropy index represents the accuracy of classification, ranging from 0 to 1. Closer to 1 indicates more accurate classification, with values above 0.8 suggesting a classification accuracy of 90% or greater32. (3) Likelihood ratio tests include Lo Mendell Rubin (LMR) test and Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT). A significant P-value (P < 0.05) indicates that a model with k classes significantly outperforms a model with k-1 classes33.

Ethical considerations

Study subjects: We employed a random sampling method to select study subjects from multiple surgical departments, ensuring diversity and representativeness in our sample. This approach helps reduce selection bias and makes our findings more widely applicable.

Standardized survey tools: We utilized validated standardized questionnaires to assess postoperative sleep disturbances and related factors. The validity and reliability of these tools have been established in relevant literature, thereby minimizing the risk of measurement bias.

Training data collectors: All researchers involved in data collection underwent training to ensure they adhered to consistent interviewing and data entry procedures, thereby reducing the likelihood of human error and bias.

Ethical review: Before the study commenced, reviewed and approved by the Second Affiliated Hospital Ethics Committee of Zunyi Medical University. Ethics approval number KYLL-2023–020. Before participating in the study, all patients provided written informed consent, and all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines, regulations, and Good Clinical Practices.

Results

Sample characteristics

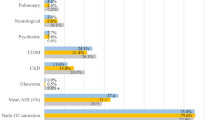

This study included a total of 400 elective surgery patients, consisting of 181 males (45.3%) and 219 females (54.8%). The median age was 50.0 (range: 39–59) years, with a median BMI of 23.6 (range: 20.7–26.7) kg/m2. Regarding educational background, 190 individuals (47.5%) had primary school/loer 118 individuals (29.5%) had high school/lower education, and 92 individuals (23.0%) had Bachelor/higher degree (Table 1).

Analysis of profiles of sleep disturbances in postoperative patients and naming

Based on the PSQI with its 7 dimensions as manifest variables, four latent profile models were established starting from the initial model. As the number of models increased, Model 4 had the lowest AIC and BIC values, but the LMRT value was not significant, indicating that Model 3 was better than Model 4. Model 3 had a higher entropy value than Model 2, indicating that Model 3 had better classification. Therefore, Model 3 was selected as the best-fitting model, as shown in Table 2.

Based on Model 3, there were significant differences in the scores of the three latent profiles in the “sleep disturbance” dimension. Considering the practical significance, they were named "Mild Sleep Disturbance Group," "Moderate Sleep Disturbance Group," and "Severe Sleep Disturbance Group," respectively. These groups included 140, 177, and 83 patients, accounting for 35.0%, 44.2%, and 20.8% of the total, as shown in Fig. 1.

Univariate analysis of profiles latent categories of postoperative patients with sleep disturbances

The results showed statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) in forms of anesthesia, BMI, duration of anesthesia, operation time, pain, anxiety, depression, and hospitalization days among different latent categories (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis of profiles latent categories of postoperative patients with sleep disturbances

The profiles of sleep disturbances were used as the dependent variable (assigned as mild sleep disturbance = 1, moderate sleep disturbance = 2, severe sleep disturbance = 3), with the mild sleep disturbance group as the reference group. Variables that showed statistical significance in the univariate analysis were included as covariates in the multivariate logistic regression. The results indicated that BMI, duration of anesthesia , pain, and anxiety were significant factors influencing different categories of postoperative sleep disturbances (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

Discussion

Postoperative sleep disturbances in patients undergoing elective surgery exhibit heterogeneity among the population

Our study found that postoperative sleep disturbances in patients undergoing elective surgery can be categorized into three groups: mild sleep disturbance group (35.0%), moderate sleep disturbance group (44.2%), and severe sleep disturbance group (20.8%). This indicates a significant heterogeneity in sleep disturbances among postoperative elective surgery patients. The mild sleep disturbance group scored low across all dimensions, suggesting that their postoperative sleep quality is relatively acceptable; however, this does not mean that this population should be overlooked regarding their postoperative sleep status. Healthcare providers should also pay attention to the postoperative sleep conditions of these patients to prevent their condition from progressing to moderate or severe sleep disturbances.

The moderate sleep disturbance group represents the largest proportion, and compared to the other two groups, they reported higher scores for daytime functional impairment. This suggests that this population may experience physiological discomfort due to the surgical impact, leading to the onset of sleep disturbances. Healthcare professionals should provide additional support to these patients and implement appropriate care measures, such as scheduling medical procedures during the day to preserve the patients’ normal sleep patterns and minimize disruptions to their sleep. Furthermore, evening care should be tailored to each patient’s condition, assisting them in drinking warm milk or honey water, and helping them assume comfortable sleeping positions to promote better sleep.

The severe sleep disturbance group scored high across all dimensions and had a higher rate of hypnotic medication use compared to the other two groups. This indicates that special attention should be paid to medication safety in this population. The use of hypnotic medications may lead to side effects such as daytime excessive sleepiness, poor drug tolerance, motor dysfunction, cognitive impairment, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms, which can even exacerbate sleep disturbances34. Therefore, healthcare providers must have a thorough understanding of the indications and contraindications for these medications when prescribing them, reinforcing medication guidance for this group, and adhering to principles of safety, appropriate dosing, and short-term use.

A higher BMI is more likely to have negative effects on sleep quality

Obesity is a significant risk factor for sleep disturbances. Our study findings reveal that a higher BMI increases the likelihood of being categorized in the moderate or severe sleep disturbance groups, consistent with the research conducted by Meurling et al.35 The possible explanation could be that accumulated fat in the abdomen and chest of obese individuals reduces lung volume, lowers chest wall and lung compliance, and increases pulmonary static recoil pressure36,37. Abdominal obesity and reduced lung capacity decrease upper airway longitudinal traction, leading to airway collapse38,39. Additionally, increased neck fat can cause upper airway obstruction and collapse, factors that contribute to recurrent hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and sleep architecture disruption during the night, thereby inducing sleep disturbances40,41,42. Short sleep duration is associated with leptin resistance and ghrelin secretion; insufficient sleep increases ghrelin’s hunger signals while reducing leptin’s satiety signals, leading to increased appetite and high-calorie food intake. This indicates a synergistic metabolic effect between obesity and sleep disturbances, with sleep disruption exerting a feedback effect on obesity43,44.

The longer the duration of anesthesia, the more likely it is to be associated with severe sleep disturbance group

The results of this study show that compared with the light and moderate sleep groups, the longer the anesthesia time, the greater the probability that an individual belongs to the heavy sleep group. It may be because commonly used clinical anesthetic and sedative drugs mainly enhance gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors and glycine receptors or inhibit excitatory receptors (dopamine receptors, nicotine, 5-hydroxytryptamine, and ionotropic glutamate receptors, etc. ) functions to exert an anesthetic effect45,46. Longer anesthesia means the substance remains in the body longer. Chemicals can act on the sleep–wake cycle to cause loss of consciousness and have certain effects on sleep in a short period through mechanisms such as changing sleep structure, affecting circadian rhythm, and regulating the sleep–wake cycle47.

The more intense the pain is, the more likely it is to cause sleep disturbances

Pain and sleep are bidirectional; pain can disrupt sleep, and insufficient sleep can increase pain sensitivity9,48,49. The findings of this study reveal that higher pain scores were more likely to be associated with moderate to severe sleep disturbance groups, and more severe pain was correlated with more severe sleep disturbances, consistent with Bailey’s research50. Research has shown that more intense pain can stimulate the patient’s dopamine system, altering their pain sensitivity and potentially intensifying emotional reactions, causing discomfort and leading to sleep quality decline or sleep disturbances51. Sleep disturbances can impact pain through compromised immune function, increased inflammatory responses, and elevated levels of cytokines such as interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and cortisol52,53,54. Hence, healthcare professionals should closely monitor postoperative patients’ pain status, promptly evaluate it, and intervene actively, as this is crucial for improving sleep quality and facilitating patients’ recovery.

The higher the anxiety score, the greater the impact on sleep

Research indicates that higher levels of anxiety are associated with poorer postoperative sleep quality55. The findings of this study suggest that individuals with higher anxiety levels have a greater likelihood of being categorized in the moderate or severe sleep disturbance groups, possibly due to the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis by anxiety, which enhances the reticuloendothelial system and excites the sympathetic nervous system, leading to increased secretion of stress hormones like cortisol and catecholamines. This can alter the release of neurotransmitters like glutamate and GABA, thereby changing sleep cycles and depth56,57. Anxiety may also disrupt melatonin secretion and function, disrupting the biological clock and the regulation of the sleep–wake cycle, leading to sleep disturbances and circadian rhythm disturbances58. Prolonged anxiety not only causes patient distress but also prolongs postoperative pain and increases the risk of postoperative delirium59,60.

Limitations and prospects of this study

This study has some limitations. Firstly, it only selected surgical patients from a tertiary hospital in Guizhou Province, limiting the scope of the research. Therefore, to enhance the generalizability of our findings, we plan to adopt a multicenter design in our future research and include a broader patient population with diverse backgrounds and health conditions. This approach will allow for a more comprehensive understanding of how surgery affects postoperative sleep across different patient groups, providing a stronger basis for clinical practice. Additionally, the subjective PSQI score used in this study may differ from the actual sleep conditions of patients. In future research, objective sleep monitoring devices could be used to evaluate postoperative sleep, providing more convincing results.

Conclusions

Our study investigated the impact of surgery on patients’ sleep status, revealing distinct classification characteristics in postoperative sleep, with different influencing factors for each potential category. While we found that some patients experienced sleep disturbances after surgery, we excluded individuals with a history of sleep disturbances during the study design to ensure sample consistency. This approach ensured that all enrolled patients exhibited normal sleep patterns prior to surgery, but it also limited our ability to make direct comparisons of sleep state changes before and after surgery. Consequently, this may have led to an underestimation of the surgical impact on postoperative sleep. We recommend that future studies incorporate longitudinal comparative data that includes both preoperative and postoperative assessments to more comprehensively investigate the effects of surgery on sleep.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the fact that the data used in this study is from the author’s master’s thesis, it is currently in the research stage, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sui, X. et al. The effects of dexmedetomidine for patient-controlled analgesia on postoperative sleep quality and gastrointestinal motility function after surgery: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, and controlled trial. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 990358 (2022).

Laitinen, L., Nurmi, M., Rautava, P., Koivisto, M. & Polo-Kantola, P. Sleep quality in women with nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 152 (2021).

Shaik, L., Boike, S., Ramar, K., Subramanian, S. & Surani, S. COVID-19 and sleep disturbances: A literature review of clinical evidence. Medicina (Kaunas) 59, 818 (2023).

Zheng, Z. et al. Meta-analysis of relationship of sleep quality and duration with risk of diabetic retinopathy. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 13, 922886 (2022).

Arvidsson, S., Arvidsson, B., Fridlund, B. & Bergman, S. Factors promoting health-related quality of life in people with rheumatic diseases: A 12 month longitudinal study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 12, 102 (2011).

Lee, S., Lee, H. J. & Cho, C. H. Mediation effect of insomnia symptoms on relation between stress and quality of life. Psychiatry Investig. 19, 229–238 (2022).

Schlagintweit, J. et al. Effects of sleep fragmentation and partial sleep restriction on heart rate variability during night. Sci. Rep. 13, 6202 (2023).

Du, J. et al. Development and validation of a nomogram for postoperative sleep disturbance in adults: a prospective survey of 640 patients undergoing spinal surgery. BMC Anesthesiol. 23, 154 (2023).

Rampes, S., Ma, K., Divecha, Y. A., Alam, A. & Ma, D. Postoperative sleep disorders and their potential impacts on surgical outcomes. J. Biomed. Res. 34, 271–280 (2019).

Luo, M., Song, B. & Zhu, J. Sleep Disturbances After General Anesthesia: Current Perspectives. Front. Neurol. 11, 629 (2020).

Lin, X. et al. Effects of esketamine on postoperative fatigue syndrome in patients after laparoscopic resection of gastric carcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 24, 185 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Gender differences in postoperative pain, sleep quality, and recovery outcomes in patients undergoing visual thoracoscopic surgery. Heliyon. 10, e39015 (2024).

Fan, Y. L., Qian, J. L., Ma, E. L., Stricker, P. A. & Zuo, Y. X. Incidence and risk factors of postoperative severe discomfort after elective surgery under general anesthesia: A prospective observational study. J. Perianesth. Nurs. 36, 253–261 (2021).

Qiu, D. et al. Effect of intraoperative esketamine infusion on postoperative sleep disturbance after gynecological laparoscopy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e2244514 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Music combined with dexmedetomidine relieves preoperative anxiety and promotes postoperative recovery in patients undergoing gynecologic laparoscopic surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Transl. Res. 16, 155–162 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Risk factors for sleep disturbances in elderly patients after thoracic surgery. Chin. J. Anesthesiol. 41, 278–281 (2021).

Gouda, W. et al. Sleep disorders in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: association with quality of life, fatigue, depression levels, functional disability, disease duration, and activity: a multicentre cross-sectional study. J. Int. Med. Res. 51, 3000605231204477 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. Postsurgery subjective cognitive and short-term memory impairment among middle-aged chinese patients. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2336985 (2023).

Gagliardi, M. et al. Can esophageal symptoms be associated with sleep disorders in esophageal rare diseases?. A prospective case-control study across achalasia, eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Minerva. Gastroenterol. (Torino) 69, 365–373 (2023).

Fang, J. et al. Effects of short-term preoperative intranasal dexmedetomidine plus conventional treatment on delirium following cardiac surgery in patients with sleep disorders. Perioper. Med. (Lond) 13, 17 (2024).

Li, G. A latent profile transition analysis and influencing factors of internet addiction for adolescents: A short-term longitudinal study. Heliyon 9, e14412 (2023).

Luo, Z. et al. Perceived stress, resilience, and anxiety among pregnant chinese women during the COVID-19 pandemic: Latent profile analysis and mediation analysis. Front. Psychol. 12, 696132 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. A latent profile analysis of emotional expression among patients with unintentional injuries. BMC Psychiatry 22, 729 (2022).

Tachaveeraphong, W. & Phattarataratip, E. The significance of modified histone h3 in epithelial dysplasia and oral cancer. Int. Dent. J. 74, 769–776 (2024).

Xu, N. et al. Analysis of the factors influencing sleep disturbances before and after surgery in patients with lung cancer. Clin. Pulm. Med. 28(336–339), 352 (2023).

Del Brutto, O. H., Mera, R. M., Del Brutto, V. J., Recalde, B. Y. & Castillo, P. R. The association between physical activity and sleep quality in stroke-free adults living in rural settings. Three villages study. Sleep Med. 70, 2–5 (2020).

Liu, X. C. et al. 2002 Study on the reliability and validity of the pittsburgh sleep quality index. Chin. J. Psychiatry 103–107, 28 (1996).

Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T. & Neckelmann, D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 52, 69–77 (2002).

Farrar, J. T., Young, J. P. Jr., LaMoreaux, L., Werth, J. L. & Poole, M. R. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 94, 149–158 (2001).

Williamson, A. & Hoggart, B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J. Clin. Nurs. 14, 798–804 (2005).

Berlin, K. S., Williams, N. A. & Parra, G. R. An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 39, 174–187 (2014).

Huang, F. et al. Distinct classes of statistical anxiety: Latent profile and network psychometrics analysis of university students. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 16, 2787–2802 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Study on the sleep quality classification and influencing factors of adult icu awake patients based on latent profile analysis: A cross-sectional survey. Nat. Sci. Sleep 15, 861–871 (2023).

Roch, C., Bergamini, G., Steiner, M. A. & Clozel, M. Nonclinical pharmacology of daridorexant: a new dual orexin receptor antagonist for the treatment of insomnia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 238, 2693–2708 (2021).

Meurling, I. J., Shea, D. O. & Garvey, J. F. Obesity and sleep: a growing concern. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 25, 602–608 (2019).

Probst-Hensch, N. et al. Causal effects of body mass index on airflow obstruction and forced mid-expiratory flow: A mendelian randomization study taking interactions and age-specific instruments into consideration toward a life course perspective. Front. Public Health 9, 584955 (2021).

Yu, W., Liang, Y., Gao, J. & Xiong, J. Study on risk factors and treatment strategies of hypoxemia after acute type a aortic dissection surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 19, 273 (2024).

Lim, D. C., Sutherland, K., Cistulli, P. A. & Pack, A. I. P4 medicine approach to obstructive sleep apnoea. Respirology 22, 849–860 (2017).

Xu, Z. et al. Association between waist circumference and lung function in American middle-aged and older adults: findings from NHANES 2007–2012. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 43, 98 (2024).

Liu, L. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and hypertensive heart disease: From pathophysiology to therapeutics. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 24, 342 (2023).

Reddy, S., Koul, P. A., Bhat, M. H., Shah, S. & Ganie, M. A. Comparison of clinical, biochemical, and polysomnographic parameters between obese and nonobese obstructive sleep apnea. Lung India 39, 261–266 (2022).

Flink, B. J. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and incidence of postoperative delirium after elective knee replacement in the nondemented elderly. Anesthesiology 116, 788–796 (2012).

Lee, J. H. & Cho, J. Sleep and obesity. Sleep Med. Clin. 17, 111–116 (2022).

Primack, C. Obesity and sleep. Nurs. Clin. North Am. 56, 565–572 (2021).

Godec, S., Gradisek, M. J., Mirkovic, T. & Gradisek, P. Ventriculolumbar perfusion and inhalational anesthesia with sevoflurane in an accidental intrathecal injection of tranexamic acid: unreported treatment options. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 47, 65–68 (2022).

Xiao, Y. et al. The 50% and 95% effective dose of remimazolam tosilate for anaesthesia induction in sleep disorders patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an up-and-down sequential allocation trial. BMC Anesthesiol 24, 48 (2024).

Rogobete, A. F. et al. Multiparametric monitoring of hypnosis and nociception-antinociception balance during general anesthesia-a new era in patient safety standards and healthcare management. Medicina (Kaunas) 57, 132 (2021).

Adam, R., Kanakarajan, S., Onyeakazi, U., Columb, M. & Galley, H. Phase II double-blind randomised controlled trial of exogenous administration of melatonin in chronic pain (DREAM-CP): a study protocol. BMJ Open 10, e034443 (2020).

Kennedy, D. L. et al. The association of sensory phenotype and concomitant mood, sleep and functional impairment with the outcome of carpal tunnel surgery. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 22, 962 (2021).

Bailey, D. R. et al. Evaluation of sleep quality and its relationship with pain, mood, and physical function after orthopaedic trauma surgery: A prospective cohort study. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 31, 341–348 (2023).

Wang, Y., Sun, K., Zhang, W., Zhang, H. & Wang, C. Pain and psychological distress: Effect of microvascular decompression on sleep disorders and obsessions in trigeminal neuralgia. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base 82, e285–e294 (2021).

Varallo, G. et al. Sleep disturbances and sleep disorders as risk factors for chronic postsurgical pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 63, 101630 (2022).

Yu, S., Xiong, Y., Lu, G. & Xiong, X. Effects of preoperative sleep disorders on anesthesia recovery and postoperative pain in patients undergoing laparoscopic gynecological surgery under general anesthesia. Mediators. Inflamm. 2022, 7998104 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. A narrative review of the reciprocal relationship between sleep deprivation and chronic pain: The role of oxidative stress. J. Pain Res. 17, 1785–1792 (2024).

Gu, X., Zhang, Y., Wei, W. & Zhu, J. Effects of preoperative anxiety on postoperative outcomes and sleep quality in patients undergoing laparoscopic gynecological surgery. J. Clin. Med. 12, 1835 (2023).

Ai, Z. et al. Validation of the thyrotoxicosis-associated insomnia model induced by thyroxine through sympathetic stimulation: Face construct predictive perspectives. Exp. Neurobiol. 30, 387–400 (2021).

Seid Tegegne, S. & Fenta Alemnew, E. Postoperative poor sleep quality and its associated factors among adult patients: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond) 74, 103273 (2022).

Zaki, N. F. et al. Depressive symptoms, sleep profiles and serum melatonin levels in a sample of breast cancer patients. Nat. Sci. Sleep 12, 135–149 (2020).

Tanaka, M. et al. Effects of the Kampo medicine Yokukansan for perioperative anxiety and postoperative pain in women undergoing breast surgery: A randomized, controlled trial. PLoS One 16, e0260524 (2021).

Yang, X. et al. Risk stratification and predictive modeling of postoperative delirium in chronic subdural hematoma. Neurosurg. Rev. 47, 152 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge all patients who participated in our study as well as the support from their families, and we also thank the investigators and staff in this clinical study for their valuable contributions.

Funding

The work was supported by grants from the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Program (Grant No. ZK[2023] General 527), The Program for Science and Technology Project of Guizhou Province. Qiankehe Platform Talents (No. [2021] 5613) and The Key Program for Science and Technology Project of Guizhou Province (No. ZK [2021] 007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.D.W.,J.Z. did conceptualization, data collection, data analysis, methodology, and writing original Draft. B.X.Y.,J.J.L.supervised methodology, wrote original draft, and reviewed & edited the manuscript. D.F., J.G, and Y.F.Y. did writing—review and editing. X.S.H. C.,S.W.H. collected data. L.K.P.S. and P.Z. G. did supervision, conceptualization, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, B., Li, J., Feng, D. et al. Latent profiles and determinants of postoperative sleep quality in elective surgery patients. Sci Rep 15, 617 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84896-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84896-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The mediating role of pain in the relationship between sleep and recovery

Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971 -) (2025)