Abstract

The discovery of novel materials is crucial for developing new functional materials. This study introduces a predictive model designed to forecast complex multi-component oxide compositions, leveraging data derived from simpler pseudo-binary systems. By applying tensor decomposition and machine learning techniques, we transformed pseudo-binary oxide compositions from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) into tensor representations, capturing key chemical trends such as oxidation states and periodic positions. Tucker decomposition was utilized to extract tensor embeddings, which were used to train a Random Forest classifier. The model successfully predicted the existence probabilities of pseudo-ternary and quaternary oxides, with 84% and 52% of ICSD-registered compositions, respectively, achieving high scores. Our approach highlights the potential of leveraging simpler oxide data to predict more complex compositions, suggesting broader applicability to other material systems such as sulfides and nitrides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery of novel materials not only enhances our understanding of fundamental physical mechanisms but also accelerates the development of new functional materials. Although newly discovered materials do not always exhibit superior properties, materials with similar compositions or crystal structures may lead to the discovery of new materials with excellent properties1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. For example, in perovskite-type oxides, structural similarity has contributed to the discovery of new materials with high electrical and catalytic properties9,10.

Multi-component materials attract significant interest in various application fields, particularly in energy materials, catalysts, and electronic materials11,12,13,14,15,16. Therefore, efficient exploration of these materials is one of the key challenges. In recent years, advances in computational materials science have enabled the generation of virtual chemical compositions by substituting constituent elements in newly discovered materials based on their crystal structures, allowing for high-precision calculations of various physical properties17,18,19. However, multi-component materials remain underexplored, and the number of known crystal structures is limited. As a result, the discovery of new materials is also crucial for computational materials science.

A challenge in exploring multi-component materials is the vast number of possible combinations of elements and composition ratios, leading to a broad search space. While combinatorial experiments and automated robotic experiments have been researched for more efficient synthesis20,21,22,23,24, the current level of efficiency is insufficient given the expanding search space. Conducting exhaustive experiments across such a wide space can lead to wasted effort and resources, making it necessary to develop a system that can predict compositions with high synthesizability. In previous research by the authors25,26, a method was developed to predict Chemically Relevant Compositions (CRC) using tensor decomposition. However, because the dimensionality of the tensor changes depending on the number of constituent elements, separate prediction models were needed for simple and multi-component compositions. This resulted in lower predictive performance for multi-component compositions, especially when the number of known data points was limited relative to the search space. Additionally, while methods exist to vectorize chemical compositions using features like atomic numbers and electronegativities of the constituent elements27,28,29, using tensor embedding vectors obtained through tensor decomposition is expected to provide representations that more directly correlate with the presence or absence of chemical compositions.

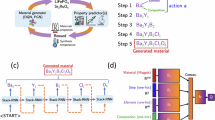

In this study, we developed a CRC prediction model using a systematic approach. The overview of this method is shown in Fig. 1. First, pseudo-binary oxide data were transformed into tensor-type representations of the end members and their composition ratios, and Tucker decomposition was applied to derive tensor embeddings for the end members. Next, chemical compositions were encoded into vector representations (compositional descriptors) using statistical features, such as the mean and standard deviation of the tensor embeddings, as described in the method shown in Fig. 2. A prediction model was then trained exclusively on pseudo-binary oxide compositions. The relationships learned by the model were subsequently evaluated through correlation analysis of the tensor embeddings of the end members. Using this trained model, we predicted the existence probabilities of pseudo-ternary and pseudo-quaternary oxide compositions. Our approach’s success in predicting multi-component compositions from pseudo-binary data indicates its potential for advancing the exploration of other anionic systems, particularly those with fewer known multi-component compounds25.

Overview of the proposed method. The target data consists of pseudo-binary, pseudo-ternary, and pseudo-quaternary oxide compositions extracted from the ICSD. These compositions are transformed into data representing the end members and their compositional ratios. First, Tucker decomposition is applied to the pseudo-binary oxide data to obtain tensor embeddings of the end members. Next, the obtained tensor embeddings are used to encode each composition into a compositional descriptor. A classification model is then trained using the encoded pseudo-binary oxide data, based on whether the compositions are registered in the ICSD. Finally, the trained classification model is used to predict the registration of encoded pseudo-ternary and pseudo-quaternary oxide compositions in the ICSD, and the predictions are evaluated against actual ICSD registrations.

This figure illustrates the method for encoding a chemical composition into a compositional descriptor. Using A2BCO5 as an example, the tensor embeddings of the end members are weighted based on their compositional ratios (AO:BO:CO2 = 2:1:1). The mean, standard deviation, and covariance between columns are then calculated and arranged to form the compositional descriptor.

Results

Tensor embeddings of end members via tucker decomposition

As shown in Fig. 3a, the Receiver Operating Characteristic-Area Under the Curve (ROC-AUC) in cross-validation varies based on the rank of the core tensor assigned to the end members. The ROC-AUC reached a maximum value of 0.88 when the core tensor rank was set to 5, confirming that the masked data within the tensor could be accurately reproduced. Figure 3b shows the ROC curve at the optimal core tensor rank, indicating that the sharp rise at the high-score side (lower left of the ROC curve) demonstrates superior prediction performance for high scores. By determining the core tensor rank in this manner, the dimensionality of the embedding vectors for the end members was set to 5.

(a) ROC-AUC performance as a function of the core tensor rank of the end members in Tucker decomposition cross-validation, with the compositional ratio rank fixed at 7. (b) ROC curves for the cases where the core tensor ranks of the end members and compositional ratios are 5 and 7, showing the highest ROC-AUC values.

Figure 4 shows a plot of the end members’ tensor embeddings reduced from 5 to 2 dimensions using t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) based on cosine distance30. It was confirmed that the end members were clustered together based on their oxidation states, and within the same oxidation state, alkali metal oxides, Group 11 oxides like Cu2O and Ag2O, as well as oxides from the sixth period such as Hg2O and Tl2O, were located close to each other. Additionally, for trivalent end members, 4f. rare earth metal oxides, 3d transition metal elements, and Group 13 element oxides were also found to be in proximity, suggesting that chemical features other than oxidation states were also captured.

Two-dimensional t-SNE plot of 5-dimensional tensor embeddings for end members, showing clusters based on oxidation states. The end members are color-coded based on their formal oxidation states: red for monovalent (A2O), green for divalent (AO), orange for trivalent (A2O3), black for tetravalent (AO2), cyan for pentavalent (A2O5), purple for hexavalent (AO3), and gray for heptavalent (A2O7).

Prediction of pseudo-ternary and quaternary oxide compositions using random forest classifier

By applying a Random Forest classifier to the tensor embeddings of the end members, we trained a model on pseudo-binary oxide compositions, and the probabilities of existence of pseudo-ternary and quaternary oxide compositions were predicted. Figure 5 shows the distribution of predicted values for compositions registered in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). The predicted values for ICSD compositions were concentrated in the high-score region. On the other hand, the peak probability for pseudo-ternary oxide compositions that were not registered in the ICSD was below 0.1, while for pseudo-quaternary compositions, the peak was around 0.55, indicating the presence of many compositions across a wide range of probabilities. This suggests that the dataset used for learning, which was limited to relatively simple pseudo-binary oxide compositions, may be insufficient to represent the complexity of more intricate end member combinations. Furthermore, the probability distributions for pseudo-ternary and quaternary oxide compositions registered in the ICSD were found to be similar, indicating that adding data for pseudo-ternary compositions to the training set could potentially improve the prediction accuracy for pseudo-quaternary compositions. The bottom histogram shows the proportion of ICSD compositions within each bin, normalized against random sampling, allowing for an evaluation of the predictive model’s performance for each probability. For pseudo-ternary oxide compositions, the model outperformed random sampling in regions with probabilities exceeding 0.6, with up to a 19-fold improvement. For pseudo-quaternary oxide compositions, performance exceeded random sampling for probabilities above 0.8, reaching a maximum improvement of 250-fold.

The top row shows histograms of ICSD compositions, and the middle row shows histograms of non-ICSD compositions. The bottom row represents the ratio of ICSD compositions in each bin, normalized by the ratio obtained from random sampling. The left panel presents the results for pseudo-ternary oxide compositions, while the right panel shows the results for pseudo-quaternary oxide compositions. The bin width for the histograms is 0.05.

For unregistered compositions, the number of compositions exceeding the probability threshold was 1,558,737 for pseudo-ternary systems and 120,863 for pseudo-quaternary systems, both of which far exceed the synthetic capabilities of a traditional laboratory. However, it should be noted that this vast number includes compositions that are only slightly different from those with the highest scores. Moreover, in practical synthesis, there is a possibility of obtaining the desired novel composition even with slight deviations in composition. Therefore, selecting systems with high synthetic feasibility and prioritizing the synthesis of compositions that exhibit maxima within those systems can significantly improve the efficiency of exploration. Figure 6 shows the distribution of the average probability across all compositions within a pseudo-ternary system for 166,650 pseudo-ternary systems (i.e., 101C3), divided based on whether they contain ICSD compositions. The 3656 systems containing ICSD compositions have higher average system probabilities compared to the 162,994 systems without ICSD compositions. This indicates that using the average system probability for each system is effective in selecting systems with a higher likelihood of containing synthesizable compositions. The upper quartile of the average system probability containing ICSD compositions is 0.73, and only 0.5% of the systems without ICSD compositions have an average system probability higher than this value. These systems, in particular, are promising candidates for synthesizing novel materials.

Discussion

In our approach, the pseudo-binary oxide compositions listed in the ICSD were converted into data capturing the end members and their compositional ratios. Using Tucker decomposition, we then derived tensor embeddings for these end members. The tensor embeddings successfully captured chemical trends, including oxidation states and periodic table positions, demonstrating that Tucker decomposition can automatically extract relevant chemical knowledge without additional input. Furthermore, by using these tensor embeddings, the complex oxide compositions were encoded into vector form, and the model trained only on pseudo-binary oxide compositions was used to evaluate the feasibility of pseudo-ternary and quaternary oxides. As a result, many known materials registered in the ICSD exhibited high probabilities of existence, whereas hypothetical oxide compositions that were not registered tended to have lower probabilities. Additionally, systems containing known compositions had higher average scores compared to those containing only unknown compositions, suggesting that selecting systems with higher average scores could enhance the efficiency of exploration in synthetic experiments. These results demonstrated that even a model trained solely on pseudo-binary oxide compositions could predict the compositions of more complex pseudo-ternary and quaternary oxides. Moreover, the proposed method is expected to facilitate efficient exploration of less-explored multi-component compounds, such as sulfides and nitrides, compared to oxides25.

Methods

Data preprocessing

We sourced chemical composition data from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD, version 2023)31. The target data were selected based on the following criteria: First, the pseudo-N-component chemical compositions must contain N distinct cations, and the formal charges must be registered as integers. Additionally, the anions were restricted to oxide ions (O2−), and the ratios of constituent elements had to be integers. We also required that a prototype structure be registered, and that the composition differed from the prototype structures of the N−1 or fewer components to exclude solid solutions. This study exclusively utilizes the compositional information provided by the ICSD, without direct consideration of crystal structures, XRD patterns, or single-phase conditions. Our approach focuses solely on the chemical validity of compositions. The cations targeted are shown in Table 1. These 101 cations appeared at least 15 times in pseudo-binary oxides; those with fewer occurrences were excluded to maintain prediction accuracy and avoid unnecessary expansion of the search space. When converting pseudo-binary oxides into tensor data, the composition ratios were adjusted to simple integer ratios by dividing the mole fractions of the end members into 11 segments and assigning the median of each segment as the representative mole ratio. This approach ensured that the tensor did not become excessively sparse. Consequently, the number of pseudo-binary, pseudo-ternary, and pseudo-quaternary oxide compositions amounted to 3182, 4807, and 660, respectively.

Creation of tensor embeddings for end members

Pseudo-binary oxide compositions were first enumerated to establish a dataset, capturing the primary compositional characteristics necessary for tensor representation. This enumeration enabled the assignment of consistent tensor embeddings, reflecting underlying chemical trends and periodic relationships within the pseudo-binary oxide systems. For example, MgAl2O4 was represented as both [MgO, AlO1.5, 1:2] and [AlO1.5, MgO, 2:1], while SrTiO3 was represented as both [SrO, TiO2, 1:1] and [TiO2, SrO, 1:1]. In these representations, while Al3+ would typically correspond to Al2O3, we adjusted the representation so that the number of cations was always 1. Since the order of the end members does not hold specific significance, both sequences were considered. These end members, along with the composition ratios, were represented as third-order tensor data. For each element of the tensor, if a known pseudo-binary composition existed, we assigned 2 points; if the end members were identical, we assigned 1 point (as no pseudo-binary composition exists), and otherwise, we assigned missing values. Tucker decomposition was applied to this tensor data using the Tensorly module32, and the rank of the core tensor was determined through Bayesian optimization with the Optuna module33, utilizing tenfold cross-validation (CV) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve along with the area under the curve (ROC-AUC) scores30.

Encoding of feature vectors for pseudo-N-component oxide compositions

Using the tensor embeddings for the end members, we weighted them by their composition ratios and calculated statistical features, including the mean, standard deviation, and covariance between columns. For pseudo-ternary and pseudo-quaternary systems, the molar fractions were varied in increments of 0.1 and 0.2, respectively. By aggregating these statistical quantities, we encoded the feature vectors for the chemical compositions. The total number of independent compositions for pseudo-binary, pseudo-ternary, and pseudo-quaternary oxides were 55,550 (computed as 101C2 × 11), 5,999,400 (computed as 101C3 × 36), and 16,331,700 (computed as 101C4 × 4), respectively.

Construction of a prediction model using a random forest classifier

To construct the prediction model, we employed only pseudo-binary oxide compositions for which tensor embeddings were generated, using these as training data and assigning 2 points for positive examples. For negative examples, in addition to combinations of two identical end members as used in Tucker decomposition, we randomly selected 10% of the 52,368 (= 55,550 − 3182) unregistered combinations in ICSD. The Random Forest Classification was implemented using the Scikit-learn module30. This process was repeated 10 times with different selections, and the average value was utilized as the prediction score for multi-component compositions. The model’s hyperparameters (i.e., the number of decision trees and the maximum depth) were tuned using Bayesian optimization, employing tenfold CV and ROC-AUC scores. Utilizing the optimized parameters, we assessed the distribution of predicted scores for both known and hypothetical pseudo-ternary and pseudo-quaternary oxide compositions.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The code used in this study will be made publicly available in a GitHub repository (https://github.com/hirhay/TensorEmbeddings4CRC/tree/main) upon acceptance of the manuscript. The repository includes all necessary code, documentation, and instructions to ensure reproducibility.

References

Hayashi, A., Noi, K., Tanibata, N., Nagao, M. & Tatsumisago, M. High sodium ion conductivity of glass–ceramic electrolytes with cubic Na3PS4. J. Power Sources 258, 420–423 (2014).

Kamaya, N. et al. A lithium superionic conductor. Nat. Mater. 10, 682–686 (2011).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field in atomically thin carbon films. Science 1979(306), 666–669 (2004).

Kamihara, Y., Watanabe, T., Hirano, M. & Hosono, H. Iron-based layered superconductor La[O1−xFx]FeAs (x = 0.05–0.12) with Tc = 26 K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3296–3297 (2008).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The materials project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4812323 (2013).

Tsujimoto, Y. et al. Infinite-layer iron oxide with a square-planar coordination. Nature 450, 1062–1065 (2007).

Collins, C. et al. Accelerated discovery of two crystal structure types in a complex inorganic phase field. Nature 546, 280–284 (2017).

Hautier, G., Fischer, C. C., Jain, A., Mueller, T. & Ceder, G. Finding natures missing ternary oxide compounds using machine learning and density functional theory. Chem. Mater. 22, 3762–3767 (2010).

Kojima, A., Teshima, K., Shirai, Y. & Miyasaka, T. Organometal halide perovskites as visible-light sensitizers for photovoltaic cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6050–6051 (2009).

King, G. & Woodward, P. M. Cation ordering in perovskites. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 5785–5796 (2010).

Matsuzaki, K., Saito, K., Ikeda, Y., Nambu, Y. & Yashima, M. High proton conduction in the octahedral layers of fully hydrated hexagonal perovskite-related oxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 18544–18555 (2024).

Morikawa, R. et al. High proton conduction in Ba2LuAlO5 with highly oxygen-deficient layers. Commun. Mater. 4, 1–9 (2023).

Wang, R. et al. Machine learning guided discovery of ternary compounds involving La and immiscible Co and Pb elements. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 1–9 (2022).

Zakutayev, A., Bauers, S. R. & Lany, S. Experimental synthesis of theoretically predicted multivalent ternary nitride materials. Chem. Mater. 34, 1418–1438 (2022).

Nomura, K. et al. Room-temperature fabrication of transparent flexible thin-film transistors using amorphous oxide semiconductors. Nature 432, 488–492 (2004).

Gunatilleke, C. B. et al. Thermal properties of the quaternary chalcogenide BaCdSnSe4. Phys. Status Solidi RRL Rapid Res. Lett. 14, 2000363 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. High-throughput discovery of novel cubic crystal materials using deep generative neural networks. Adv. Sci. 8, 2100566 (2021).

Merchant, A. et al. Scaling deep learning for materials discovery. Nature 624, 80–85 (2023).

Carlsson, A., Rosen, J. & Dahlqvist, M. Finding stable multi-component materials by combining cluster expansion and crystal structure predictions. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 1–10 (2023).

Ludwig, A. Discovery of new materials using combinatorial synthesis and high-throughput characterization of thin-film materials libraries combined with computational methods. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 1–7 (2019).

Service, R. F. AI-driven robotics lab joins the hunt for materials breakthroughs. Science 380, 230 (2023).

Abolhasani, M. & Kumacheva, E. The rise of self-driving labs in chemical and materials sciences. Nat. Synth. 2, 483–492 (2023).

Szymanski, N. J. et al. An autonomous laboratory for the accelerated synthesis of novel materials. Nature 624, 86–91 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Navigating phase diagram complexity to guide robotic inorganic materials synthesis. Nat. Synth. 3, 606–614 (2024).

Hayashi, H., Seko, A. & Tanaka, I. Recommender system for discovery of inorganic compounds. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 1–7 (2022).

Seko, A., Hayashi, H., Kashima, H. & Tanaka, I. Matrix- and tensor-based recommender systems for the discovery of currently unknown inorganic compounds. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 013805 (2018).

Antunes, L. M., Grau-Crespo, R. & Butler, K. T. Distributed representations of atoms and materials for machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 1–9 (2022).

Seko, A., Hayashi, H. & Tanaka, I. Compositional descriptor-based recommender system for the materials discovery. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 241719 (2018).

Ward, L. et al. Matminer: An open source toolkit for materials data mining. Comput. Mater. Sci. 152, 60–69 (2018).

Fabianpedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Zagorac, D., Muller, H., Ruehl, S., Zagorac, J. & Rehme, S. Recent developments in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database: Theoretical crystal structure data and related features. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 52, 918–925 (2019).

Kossaifi, J., Panagakis, Y., Anandkumar, A. & Pantic, M. TensorLy. J. Mach. Learn. Res. https://doi.org/10.5555/3322706.3322732 (2019).

Akiba, T., Sano, S., Yanase, T., Ohta, T. & Koyama, M. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 2623–2631. https://doi.org/10.1145/3292500.3330701 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JST FOREST (Grant Number JPMJFR223X) and JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers JP23H01670 and JP23K17836) for H.H., and JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number JP21H04621) for I.T.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H. conceived the idea of using tensor embeddings for materials discovery through machine learning techniques. I.T. supervised the project. Both authors contributed to the analysis of the results and the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hayashi, H., Tanaka, I. Data-driven prediction of chemically relevant compositions in multi-component systems using tensor embeddings. Sci Rep 15, 1448 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85062-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85062-z