Abstract

To investigate how PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) affect the left ventricular function in mice with myocardial infarction (MI) and through what mechanisms they exert their effects. In vivo experiments were conducted using 27 female BALB/c mice, which were divided equally into 3 groups. Cardiac function was assessed by ultrasound. Heart tissue and breast cancer tumor samples were isolated, and the content of cGAMP was measured using LC-MS/MS. The extent of myocardial infarction was evaluated by Masson staining. In vitro experiments involved dividing macrophages, treated with different inducers, into 8 groups. Protein expression levels in each group were analyzed by Western blotting, and the macrophages were transplanted into experimental mice for observation. In the in vivo experiments, ultrasound examination showed that PD-L1 mAb improved cardiac function in mice with breast cancer and MI. Both cGAMP content measurement and Masson staining results indicated that PD-L1 mAb had a therapeutic effect on mice with breast cancer and MI, improving the infarct condition and slowing tumor progression. In vitro Western blotting analysis revealed that PD-L1 mAb can modulate the CD47/SHP2/SIRPα/SYK/FcγR signaling pathway, thereby affecting breast cancer. Treatment with a STING inhibitor significantly reduced the cGAMP effect, leading to improved left ventricular function in mice with MI. PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies improve left ventricular function in mice with myocardial infarction by modulating the CD47/SHP2/SIRPα/SYK/FcγR signaling pathway in tumor-associated macrophages and inhibiting the expression of cGAMP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is the leading malignant tumor worldwide1, and due to its relatively good prognosis, the quality of life of breast cancer patients has increasingly garnered attention. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the main comorbidities and leading causes of death among breast cancer patients2,3,4, significantly impacting their quality of life. CVD shares many risk factors with breast cancer, such as age, obesity, and smoking, and is also a major adverse effect of antitumor therapies for breast cancer5,6. Foreign studies have found that the occurrence of breast cancer may be related to estrogen levels, and reducing estrogen levels can inhibit tumor proliferation and invasion. Endocrine therapy, which effectively lowers estrogen levels, is commonly used in clinical practice for breast cancer patients7,8. Estrogen levels are also related to lipid levels and play an important role in cardiovascular protection. In this study, we aim to investigate a mouse model of breast cancer combined with myocardial infarction.

CD47, known as integrin-associated protein, is a membrane protein in the immunoglobulin superfamily that plays significant roles in various cellular functions, such as proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and immune homeostasis9,10. CD47 expression is abnormally elevated in breast cancer cells and is associated with poor prognosis11,12. In the tumor microenvironment, CD47 interacts with signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) on the surface of macrophages, triggeringa signaling cascade that inhibits phagocytosis and promotes breast cancer progression. CD47 expression is positively correlated with the infiltration of monocytes and tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) in ovarian cancer13. Monocytes and TAM are recruited to the tumor site by chemokines secreted by tumoror stromal cells14,15,16. Hence, it can be hypothesized that similar interactionsmay occur in breast cancer.

Immunoglobulin G Fc receptor (FcγR) is a group of surface glycoproteins belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily, expressed on almost all leukocytes as specific receptors. FcγR interacts with IgG receptor proteins to produce a series of physiological and pathological effects, maintaining physiological balance and, under specific conditions, participating in immune damage, mediating immune-related diseases, and closely involved in tumor progression17. Programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (programmed cell death 1 ligand 1, PD-L1) are expressed on the surfaces of immune cells such as T cells and NK cells, as well as on tumor cells, acting as important immune inhibitory molecules. The binding of PD-1 to PD-L1 inhibits T cell activity18. Atezolizumab is an anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody that has been studied in several clinical trials for the treatment of breast cancer, especially triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)19,20,21. Atezolizumab blocks the interaction between PD-L1 and PD-1, relieving immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment and activating the antitumor activity of T cells. PD-L1 is highly expressed in breast cancer patients, particularly in tumor-associated immune cells, providing a theoretical basis for the application of Atezolizumab in breast cancer. This study will focuson the use of Atezolizumab in investigating breast cancer combined with myocardial infarction.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals and materials

One hundred twenty-nine 6-week-old female BALB/c mice, weighing 18–20 g, were purchased from Henan Skebes Biological Technology Co., Ltd. [SCXK(YU)2020-0016] and housed at the Animal Research Center of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University. The environmental conditions were maintained at a temperature of 22–26 °C, relative humidity of 40–60%, with a 12 h/12 h light-dark cycle. All mice were raised in pathogen-free conditions and provided with sufficient food and water. 4T1 cells (mouse breast cancer cells), human monocyte THP-1 cells, and mouse cardiomyocytes (MCM) were obtained from the China Cell Line Resource Center. Fetal bovine serum and DMEM low-glucose medium were purchased from Gibco. The PD-L1 monoclonal antibody Atezolizumab and the STING inhibitor C-176 were purchased from Selleck. CD47-OE, KD-NC, SHP2-KD, OE-NC, and SHP2-OE were purchased from Genescript (Nanjing, China). The INTERFERin® kit was purchased from Selleck, and the Vevo2100 small animal ultrasound imaging system was obtained from Visual Sonics, Canada.

Establishment and grouping of animal models of breast cancer complicated with myocardial infarction

All animal experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with China’s Public Health Service Policy and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University (Approval No: S00352). The procedures fully complied with the approved guidelines and the ARRIVE guidelines. A total of 27 mice were randomly divided into three groups using simple random sampling: the sham group, the Model group, and the Model + PD-L1 monoclonal antibody group. The cage positions were randomized to minimize the impact of environmental factors on the experimental results, ensuring consistency in environmental conditions across groups.

To begin, breast cancer models were established in the two model groups. Before the implantation of 4T1 cells, they were maintained in RPMI 1640 (ATCC) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies), and then inoculated into the abdominal fat pads of 6-week-old mice in the Model and Model + PD-L1 monoclonal antibody groups (4 × 10^5 cells per mouse). On day 7 after the inoculation of breast cancer cells (before the tumors became visible), intraperitoneal injections of Atezolizumab were started at a concentration of 20 mg/mL. Myocardial infarction (MI) models were also constructed in the two model groups by permanently ligating the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) to induce myocardial infarction. Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of ketamine (100 mg/kg body weight) and xylazine (10 mg/kg body weight), followed by intubation with a small animal ventilator and air ventilation. A thoracotomy was performed by scraping the chest wall at the left fourth intercostal space. The LAD coronary artery was identified and permanently ligated approximately 3 mm below the left atrium using an 8 − 0 monofilament nylon suture. The chest cavity was closed with 6 − 0 sutures, and buprenorphine was administered to the mice postoperatively for pain relief. Sham-operated (sham group) animals (MI control) underwent a similar procedure but without the ligation of the artery, using a suture to pass through the artery without tying it. The success of the surgery was ensured, and the recovery of the mice was observed.

Atezolizumab was injected once weekly for three weeks. Tumor volumes were measured using digital calipers when the primary tumors first became palpable (day 10), as well as on days 12, 14, 16, and at the time of sacrifice (day 20). Tumor volume was calculated asV=(L×W^2)/2. Mice exposed to myocardial infarction were sacrificed after the primary tumor reached a specific volume and cancer-specific death criteria (IACUC euthanasia standards) were met, selecting a period of 20 days. At the time of sacrifice, tumor and heart tissues were collected for cGAMP detection, Masson staining, TTC staining, tumor mass measurement, and immunohistochemistry to observe cGAS markers.

First Validation Experiment: Thirty-six mice were randomly divided into four groups: Breast cancer group, Breast cancer + cGAMP group, Breast cancer + MI group, and Breast cancer + cGAMP + MI group. Ultrasound was used to measure the LVEF (left ventricular ejection fraction) and FS (fractional shortening) indices in each group. Heart tissue was evaluated by Masson staining. Western blot experiments were conducted to validate protein expression, and ELISA was used to detect the levels of cGAMP, IL-1β, and IFNα.

Second Validation Experiment: Eighteen mice were equally divided into two groups: Breast cancer group and Breast cancer + Atezolizumab group. Immunohistochemical staining was performed to observe CD47 expression, and Western blot experiments were conducted to detect protein expression.

Cardiac function ultrasound examination in mice

Mice in each group were intraperitoneally anesthetized with 2% sodium pentobarbital, and their cardiac function was assessed using an ultrasound detection system to measure ejection fraction (EF), fractional shortening (FS), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), and left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD).

LC-MS/MS detection of cGAMP levels

After collecting serum, 250 µL of extraction solution was used to resuspend the serum, followed by a 30-minute incubation at -20 °C. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation, and the precipitate was re-extracted with 250 µL of extraction solution. The supernatant was vacuum-dried, and the precipitate was dissolved in 100 µL of ammonium acetate buffer solution. After centrifugation, the supernatant was used for LC-MS/MS to detect the cGAMP content in the serum.

Masson staining experiment

Heart tissues were fixed and dehydrated using an ethanol gradient (75%, 85%, 90%, 95%, and 100%), cleared with xylene, and embedded in paraffin using an embedding machine. For Masson staining, the paraffin sections were deparaffinized, hydrated, and then stained sequentially: Weigert’s iron hematoxylin for 8 min, Ponceau for 5 min, rinsed with distilled water for a few seconds, followed by Masson’s composite staining solution for 5 min, differentiated with phosphomolybdic acid for 5 min, and stained with aniline blue for 5 min before being mounted for observation.

TTC staining

TTC staining was used to measure the infarct area in mouse hearts. The heart tissue was frozen at -20 °C for 30 min, and six 2-mm-thick coronal slices were cut. These slices were stained with 2% TTC staining solution at 37 °C for 15–20 min in the dark, rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), photographed, and the infarct area was analyzed using Image J software.

Immunohistochemical staining

Direct immunohistochemical staining was performed using a kit from Meixin Medical Technology Co., Ltd., along with polymer-labeled McAbCK-Pan (clone AE1/AE3) and TTF-1 (clone 305). Frozen sections were fixed, washed with water, blocked with blocking solution for 1 min, and rinsed with buffer solution. The sections were incubated with antibodies at room temperature for 3 min, rinsed with buffer solution, and DAB was applied for 3 min to visualize staining. The sections were then counterstained, dehydrated, cleared, sealed, and observed under a microscope.

Cell culture grouping and nude mouse model

4T1 cells were transfected with CD-47 OE lentivirus. THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C with 5% CO2. When the cells reached logarithmic growth, THP-1 cells were centrifuged and resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium. PMA was added, and the cells were counted under a microscope, adjusting the density of THP-1 cells to 5 × 10^5/mL. The final concentration of PMA was set at 100 ng/mL, and 2 mL of cells were seeded into each well of a six-well plate. After 48 h, macrophage differentiation was confirmed microscopically. Macrophages were then cultured under hypoxic conditions (1% O2) at 37 °C in low-glucose DMEM medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin.

THP-1 macrophages were divided into eight groups: KD-NC group (①), SHP2-KD group (②), OE-NC group (③), SHP2-OE group (④), KD-NC + Atezolizumab group (⑤), SHP2-KD + Atezolizumab group (⑥), OE-NC + Atezolizumab group (⑦), and SHP2-OE + Atezolizumab group (⑧). INTERFERin® was used to transfect THP-1 cells with KD-NC (negative control lentivirus for gene knockdown), SHP2-KD (SHP2 gene knockdown), OE-NC (negative control lentivirus for gene overexpression), and SHP2-OE (SHP2 gene overexpression) plasmids according to the kit instructions. Atezolizumab was used at a concentration of 50 µg/mL for 48 h. After co-culturing the eight groups of THP-1 macrophages with breast cancer 4T1 cells, they were implanted into the abdominal fat pads of 48 six-week-old mice (4 × 10^5 cells per mouse). Tumor growth was observed 7 days later, and mouse conditions were monitored and recorded. After 21 days, mice were euthanized with CO2, and their tumor tissues were collected to measure tumor size. All animal experiments adhered to the guidelines for animal care and use published by the institutional animal ethics committee.

Mouse cardiomyocytes (MCMs) were divided into the following groups after different treatments: NC group, cGAMP group, NC + C-176 group, and cGAMP + C-176 group. MCM cells were cultured under hypoxic conditions (1% O2) at 37 °C in low-glucose DMEM medium containing 3-5% fetal bovine serum, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin. The cGAMP stimulation concentration was 5 µg/mL for 24 h, and the C-176 stimulation concentration was 5 µM for 16 h.

Western blotting

Myocardial tissue was lysed using RIPA solution. Total protein was extracted by adding RIPA lysis buffer at a concentration of 100 g/L, and protein concentration was measured using a BCA protein assay kit. The protein samples were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The PVDF membrane was incubated at room temperature for 2 h in 1×TBST containing 5% non-fat milk. It was then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody dilutions. After washing, the PVDF membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10,000) for 2 h. Protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescent (ECL) substrate, and exposed on X-ray film. Protein expression was normalized to GAPDH, and grayscale values of the protein bands were measured using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences between two groups were analyzed using t-tests, and comparisons among three or more groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.0. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

PD-L1 monoclonal antibody atezolizumab improves cardiac function in a breast cancer combined with myocardial infarction model

Cardiac function in each group of mice was assessed using ultrasound. The results showed that compared to the sham group, the Model group had significantly reduced echocardiography measurements of EF and FS, and increased LVEDD and LVESD. Compared to the Model group, the Model + PD-L1 antibody group showed a significant increase in EF and FS, and a reduction in LVEDD and LVESD, with statistically significant differences (Fig. 1). These results suggest that the PD-L1 monoclonal antibody atezolizumab improves cardiac function in the breast cancer combined with myocardial infarction model.

PD-L1 monoclonal antibody atezolizumab specifically ameliorates myocardial infarction injury in a breast cancer and myocardial infarction model via the cGAMP-STING pathway

LC-MS/MS analysis of cGAMP content in each group showed a significant increase in cGAMP levels in the Model group compared to the sham group. In the Model + PD-L1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) group, cGAMP levels were significantly reduced compared to the Model group. Results from Masson staining and TTC staining demonstrated that the extent of myocardial infarction was significantly higher in the Model group compared to the sham group. In the Model + PD-L1 mAb group, the myocardial infarction extent was improved, with significant differences observed (Fig. 2).

PD-L1 monoclonal antibody atezolizumab alleviates myocardial infarction damagein the breast cancer combined with myocardial infarction model. (A) Comparison of cGAMP levels in the sham, Model, and Model + PD-L1 antibody groups. (B) Masson staining results of myocardial infarction. (C) TTC staining of myocardial infarction damage in each group. (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01)

In the validation experiments, compared to the Breast cancer group, the Breast cancer + cGAMP group showed increased protein expression of P-STING, NLRP3, IL-1β, and GSDMD, with a decrease in LVEF and FS indices measured by ultrasound. Masson staining revealed mild myocardial infarction, and cGAMP, IL-1β, and IFNα levels were elevated. Compared to the Breast cancer + MI group, the Breast cancer + cGAMP + MI group exhibited increased protein expression of P-STING, NLRP3, IL-1β, and GSDMD, with a decrease in LVEF and FS indices measured by ultrasound. Masson staining showed severe myocardial infarction, and cGAMP, IL-1β, and IFNα levels were significantly elevated (Fig. 3).PD-L1 monoclonal antibody Atezolizumab specifically ameliorates myocardial infarction injury in a breast cancer and myocardial infarction model via the cGAMP-STING pathway.

(A) Ultrasound measurement of LVEF and FS indices in the hearts of mice from four groups: Breast cancer group, Breast cancer + cGAMP group, Breast cancer + MI group, and Breast cancer + cGAMP + MI group. (B) Masson staining to assess myocardial infarction in the hearts of mice from the four groups. (C) Western blot analysis of P-STING, NLRP3, IL-1β, and GSDMD protein expression in the four groups. (D) ELISA measurement of cGAMP, IL-1β, and IFNα levels in the four groups. (*P < 0.01)

PD-L1 monoclonal antibody atezolizumab reduces tumor growth in the breast cancer combined with myocardial infarction model

Tumor tissue evaluation in the model group and model + PD-L1 monoclonal antibody

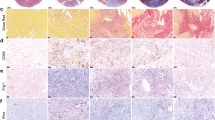

Tumor tissues from mice in the Model group and the Model + PD-L1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) group were removed and weighed. We found that, compared to the Model group, the tumor weight was significantly reduced in the Model + PD-L1 mAb group (Fig. 4A). Immunohistochemistry results showed that the cGAS levels in the Model + PD-L1 mAb group were significantly lower compared to the Model group (Fig. 4B).

PD-L1 monoclonal antibody Atezolizumab can slow tumor growth in a breast cancer and myocardial infarction model. (A) Comparison of tumor growth between the Model group and the Model + PD-L1 mAb group. (B) Immunohistochemistry to detect cGAS levels in the Model group and the Model + PD-L1 mAb group. (C) Immunohistochemistry staining to detect CD47 levels in the Breast cancer group and the Breast cancer + Atezolizumab group. (D) Western blot analysis of CD47, P-STAT3, Myc, P-SHP2, SIRPα, FcγR, P-SYK, and P-STING protein expression in the Breast cancer group and the Breast cancer + Atezolizumab group.

In the validation experiments, compared to the Breast cancer group, the Breast cancer + Atezolizumab group showed decreased protein expression of CD47, P-STAT3, Myc, P-SHP2, and SIRPα, while the protein expression of FcγR, P-SYK, and P-STING was increased (Fig. 4C and D). These results indicate that PD-L1 monoclonal antibody Atezolizumab can alleviate tumor growth in a breast cancer and myocardial infarction model. In the tumor model, PD-L1 activation of its receptor leads to the activation of the IRE1α/XBP-1 signaling pathway, promoting IL-6 transcription. After IL-6 binds to its receptor, it promotes STAT3 phosphorylation, which in turn promotes PD-L1 transcription and Myc transcription. Myc upregulates CD47 expression, and CD47 interacts with SIRPα, leading to SHP2 self-phosphorylation and activation of the “Don’t eat me” signal. Phosphorylated SHP2 also inhibits SYK phosphorylation. FcγR promotes SYK phosphorylation, and phosphorylated SYK activates the “eat me” signal. FcγR and SIRPα have mutual inhibitory effects (Fig. 5).

PD-L1 monoclonal antibody atezolizumab modulates the CD47/SHP2/SIRPα/SYK/FcγR signaling pathway in tumor-associated macrophages to affect breast cancer

In vitro experiments showed that in Group ②, the expression of SHP2, P-SHP2, and P-SIRPα proteins decreased, while P-SYK and P-FcγR proteins increased compared to Group ①. In Group ④, SHP2, P-SHP2, and P-SIRPα protein expressions increased, while P-SYK and P-FcγR decreased compared to Group ③. Similarly, in Group ⑤, SHP2, P-SHP2, and P-SIRPα decreased, while P-SYK and P-FcγR increased compared to Group ①. When comparing Group ⑥ to Group ⑤, SHP2, P-SHP2, and P-SIRPα decreased, while P-SYK and P-FcγR increased. Tumor sizes were compared across the eight groups, with moderate sizes in Groups ① and ③, very small sizes in Groups ② and ⑥, the largest size in Group ④, and a smaller tumor size in Group ⑧ than in Group ④. Tumor sizes in Groups ⑤ and ⑦ were larger than those in Groups ② and ⑥ (Fig. 6). These results suggest that PD-L1 monoclonal antibody atezolizumab modulates the CD47/SHP2/SIRPα/SYK/FcγR signaling pathway in tumor-associated macrophages to affect breast cancer.

PD-L1 monoclonal antibody atezolizumab affects breast cancer by regulating the CD47/SHP2/SIRPα/SYK/FcγR signaling pathway in tumor-associated macrophages. (A) Diagram showing the expression levels of SHP2, P-SHP2, P-SIRPα, P-SYK, and P-FcγR proteins in eight groups: KD-NC group (①), SHP2-KD group (②), OE-NC group (③), SHP2-OE group (④), KD-NC + Atezolizumab group (⑤), SHP2-KD + Atezolizumab group (⑥), OE-NC + Atezolizumab group (⑦), and SHP2-OE + Atezolizumab group (⑧), with statistical data analysis. (B) Comparison of tumor growth among the eight groups. (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01)

PD-L1 monoclonal antibody inhibits cGAMP expression by modulating the CD47/SHP2/SIRPα/SYK/FcγR pathway in tumor-associated macrophages, improving left ventricularfunction in mice with myocardial infarction

In in vitro cardiomyocyte experiments, Western blotting results showed that compared to the NC group, P-STING, P-TBK1, P-IRF3, NLRP3, IFNβ, and NOX4 protein expressions were significantly elevated in the cGAMP group. Compared to the cGAMP group, P-STING, P-TBK1, P-IRF3, NLRP3, IFNβ, and NOX4 expressions were significantly reduced in the NC + C-176 and cGAMP + C-176 groups. There were no significant differences in protein expression between the NC + C-176 and cGAMP + C-176 groups (Fig. 7). These results indicate that the PD-L1 monoclonal antibody inhibits cGAMP expression by modulating the CD47/SHP2/SIRPα/SYK/FcγR signaling pathway in tumor-associated macrophages, thereby improving left ventricular function in mice with myocardial infarction.

Discussion

CD47, also known as integrin-associated protein, is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. CD47 binds to its ligands to inhibit macrophage-mediated phagocytosis, resulting in immune evasion, and is thus called the “don’t eat me” signal10. CD47 is a transmembrane protein with a relative molecular mass of 5.0 × 10⁴, mainly expressed on the surface of cancer cells. It interacts with ligands such as thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) and signal-regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα), playing a role in several cellular processes including apoptosis, proliferation, adhesion, and migration. SIRPα is a receptor expressed on phagocytic cells such as macrophages22. Recent studies have reported abnormal expression of CD47 in various cancers. Tumor cells with high levels of CD47 have the ability to evade the innate immune system and thus survive better compared to CD47-negative cells in the patient’s blood10,23,24,25. Targeting CD47 with antibodies and subsequently reactivating the innate immune system against transformed cells has shown great promise in preclinical studies of various hematological malignancies and sarcomas26,27,28,29.

In recent years, studies have shown that changes in the immune system play an important role in the development of breast cancer, and immunotherapy has been regarded as a breakthrough in cancer treatment30. Immunotherapy refers to a treatment method that utilizes tumor antigens to regulate the body’s immune functions, enhancing antitumor immunity within the tumor microenvironment to inhibit tumor growth. The efficacy of immunotherapy relies mainly on the antigen-specific T cell response. Effective antitumor immune responses consist of three key steps: activation of tumor-associated T cells, infiltration, and the killing of tumor cells. A failure in any of these steps can lead to tumor immune evasion. Breast cancer is a type of tumor that can produce immune responses. In most types of breast cancer, tumor progression is associated with changes in the tumor immune microenvironment, indicating that immunotherapy may be applicable and effective in treating breast cancer. Based on the high expression of the “don’t eat me” CD47 signal in tumor cells, CD47 has been identified as a therapeutic target for malignancies.

Macrophages play a key role in immune surveillance by phagocytosing tumor cells31,32. With the involvement of Fcγ receptors, macrophages also contribute to the clinical success of therapeutic antibodies through antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP)33,34,35. Phagocytosis depends on a balance between pro-phagocytic and anti-phagocytic signals on target cells. Initially observed on red blood cells, CD47 inhibits phagocytosis by binding to SIRPα on circulating phagocytes36. Both solid and hematologic malignancies overexpress CD47 to hijack this mechanism, protecting cancer from immune detection and clearance37,38. To date, growing evidence suggests that blocking the CD47/SIRPα axis can reactivate the phagocytic function of macrophages. In mouse tumor models, tumor-activating antibodies that inhibit this phagocytic checkpoint have been shown to enhance therapeutic efficacy39,40, and SIRPα-deficient macrophages activate cytotoxic T cells through immunogenic antigen presentation41. Notably, recent clinical studies have demonstrated that disrupting the CD47/SIRPα axis, in combination with therapeutic antibodies, significantly improves outcomes42. Mechanistically, CD47 recognition by SIRPα triggers phosphorylation of its cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs (ITIMs), leading to the recruitment of tyrosine phosphatases SHP1 and SHP243,44. Once activated, SHP2 acts on Fcγ receptor SYK, dephosphorylating it and inhibiting its function.

When PD-1 binds to PD-L1, SHP2 is activated, promoting its function and further inhibiting Fcγ receptor endocytosis and phagocytosis. However, PD-L1 monoclonal antibody treatment can significantly inhibit SHP2 function, allowing SYK to be activated, thereby enhancing Fcγ receptor endocytosis and phagocytosis. Without intervention, the high expression of the CD47 “don’t eat me” signal accelerates the progression of breast cancer. Following PD-L1 monoclonal antibody treatment, the “don’t eat me” signal can be converted into an “eat me” signal, alleviating breast cancer progression.

Studies suggest that nucleic acids can act as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) under conditions of cellular damage, triggering strong immune responses45. To maintain immune system stability, the cGAS-STING pathway is precisely regulated, with the main sensor being cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS). cGAS recognizes cytoplasmic DNA and catalyzes the production of cGAMP (cyclic GMP-AMP), which binds to the stimulator of interferon genes (STING), promoting the expression and secretion of IFN-I and other immune mediators46. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) has become a key regulator of both innate and adaptive immunity, activating in response to exogenous and endogenous DNA binding. It then activates TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), leading to the expression of type I IFNs and inflammatory cytokines47. In cardiomyocytes, cGAMP enhances STING function, activating TBK1, which in turn activates IRF3. Activated IRF3 promotes the secretion of NLRP3, IFNα/β, and other pro-inflammatory factors, exacerbating myocardial infarction. It is known that DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are one of the most severe forms of DNA damage, potentially leading to mutations, genomic instability, or cell death if not repaired48. In the breast cancer combined with myocardial infarction mouse model, DNA damage caused by both later-stage breast cancer and myocardial infarction leads to DSBs. cGAS detects large amounts of dsDNA and catalyzes the production of cGAMP, which further exacerbates myocardial infarction. In this study, it was confirmed that PD-L1 monoclonal antibody can inhibit cGAMP production and thus alleviate this situation.

In conclusion, the PD-L1 monoclonal antibody improves left ventricular function in mice with myocardial infarction by inhibiting cGAMP production through regulation of the CD47/SHP2/SIRPα/SYK/FcγR signaling pathway in tumor-associated macrophages (Fig. 8). In previously published mouse models, PD1/PD-L1 inhibitors have been shown to exacerbate cardiovascular pathogenesis or have no effect on myocardial infarction49. Therefore, when PD1/PD-L1 inhibitors enhance systemic inflammatory responses, how can this lead to a reduction in infarct size and improvement in cardiac function? To address this question, this study provides a scientifically plausible explanation: the dual role of inflammatory responses. Inflammation is a natural response of the body to injury and disease. It can be protective, helping to clear pathogens and promote tissue repair; however, it can also be harmful, leading to tissue damage and disease progression. In the context of myocardial infarction, a moderate inflammatory response is beneficial for clearing necrotic tissue and initiating the repair process, but an excessive inflammatory response exacerbates the damage. PD1/PD-L1 not only plays a role in immune checkpoints but also in regulating inflammatory responses. PD1/PD-L1 inhibitors work by blocking the binding of PD1 and PD-L1, releasing the suppression of T cells, and thus enhancing immune system activity. This can lead to two opposing effects: in cancer treatment, it helps the immune system attack cancer cells more effectively. In non-tumor conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases, it can exacerbate inflammatory responses, leading to more tissue damage. The key finding of this study is that under tumor conditions, the death of tumor cells releases cGAMP into the bloodstream, thereby worsening the myocardial infarction. PD1/PD-L1 inhibitors can promote the “eat me” signal in macrophages, leading to the phagocytosis of tumor cells and preventing further cGAMP from affecting myocardial infarction. Additionally, PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies effectively inhibit cGAMP production by regulating the CD47/SIRPα signaling axis. This action directly alleviates the cGAS-STING pathway-mediated inflammatory response post-myocardial infarction, thereby improving left ventricular function. Restoring left ventricular function is crucial for the long-term prognosis of myocardial infarction patients, and this finding has significant clinical implications. Furthermore, PD1/PD-L1 inhibitors may affect the function of different immune cell subpopulations, for example, increasing the proportion of anti-inflammatory cells and reducing the activity of pro-inflammatory cells, thereby achieving overall inflammatory balance. Different mouse models may have different genetic backgrounds and disease states, which can influence the effects of PD1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Therefore, the observed results may vary depending on the model.

In summary, although PD1/PD-L1 inhibitors are generally thought to enhance immune responses and inflammation, in specific cardiovascular disease models, they may protect against myocardial infarction by modulating the function of immune cells and maintaining inflammatory balance, manifested as a reduction in infarct size and improvement in cardiac function. The application of PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies in myocardial infarction models demonstrates their potential therapeutic value in non-cancer diseases. Although PD-L1 inhibitors are currently primarily used for cancer immunotherapy, the findings show that they have significant effects in regulating the immune system and improving cardiac function, providing new evidence for expanding the indications of PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies. Additionally, the combination therapy strategy targeting the CD47/SIRPα axis and PD-L1 antibodies has shown progress in cancer immunotherapy, with studies demonstrating that this combination can significantly enhance the efficacy of tumor immunotherapy [52–53]. This study extends this mechanism to the cardiovascular field, suggesting that PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies may not only play a role in tumors but can also improve tissue repair and remodeling by enhancing macrophage clearance after myocardial injury. Of course, the double-edged sword effect of immune modulation in myocardial infarction cannot be ignored. While a moderate immune response is beneficial for clearing damaged cells and promoting tissue repair, excessive immune activation can lead to further myocardial injury and adverse reactions such as fibrosis. Future research should focus on how PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies fine-tune the immune response after myocardial infarction to avoid the side effects of excessive activation. Although Atezolizumab has shown excellent performance in cancer immunotherapy, its role in myocardial infarction and other non-tumor-related inflammatory diseases is relatively limited. While the enhanced immune response by Atezolizumab in this study may help more effectively clear necrotic myocardial cells and promote tissue repair and remodeling, there are currently no large-scale clinical trials specifically investigating the application of Atezolizumab in acute inflammatory responses caused by myocardial infarction. However, some studies are exploring the potential applications of immune checkpoint inhibitors (such as PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors) in cardiovascular diseases. Future research can focus on the specific role of Atezolizumab in the inflammatory response after myocardial infarction, evaluating its potential in immune modulation while also paying attention to its possible side effects on cardiac tissue. In conclusion, Atezolizumab may exert certain effects on acute inflammation and immune regulation post-myocardial infarction by influencing immune checkpoint regulation, but its specific effects require further validation through more clinical studies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

International Agency for Research on Cancer. World cancer day: Breast cancer overtakes lung cancer as leading cause of cancer worldwide. IARC showcases key research projects to address breast cancer [EB/OL]. -02-04) [2023-02-20]. (2021). https://www.iare.who.int/news-events/world-cancer-day-2021/

Connor, A. E. et al. Comorbidities and the risk of cardiovascular disease mortality among racially diverse patients with breast cancer. Cancer 127(15), 2614–2622 (2021).

Abdel-Qadir, H. et al. A population-based study of cardiovascular mortality following early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Cardiol. 2(1), 88–93 (2017).

Sturgeon, K. M. et al. A population-based study of cardiovascular disease mortality risk in US cancer patients. Eur. Heart J. 40(48), 3889–3897 (2019).

Padegimas, A., Clasen, S. & Ky, B. Cardioprotective strategies to prevent breast cancer therapy-induced cardiotoxicity. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 30(1), 22–28 (2020).

Mehta, L. S. et al. Cardiovascular disease and breast cancer: where these entities intersect: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 137(8), e30–e66 (2018).

Kalinina, T. et al. Expression of estrogen receptor-and progesterone receptor-regulating microRNAs in breast cancer. Genes 12(4), 582 (2021).

Nsonwu-Anyanwu, A. C. et al. Evaluation of biomarkers of oxidative stress and female reproductive hormones in post menopausal women with breast cancer in Southern Nigeria. Niger J. Clin. Pract. 24(2), 168–176 (2021).

Brightwell, R. M. et al. The CD47 don’t eat me signal is highly expressed in human ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 143(2), 393–397 (2016).

Willingham, S. B. et al. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha(SIRPa)interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109(17), 6662–6667 (2012).

Chen, Y., Klingen, T. A., Aas, H., Wik, E. & Akslen, L. A. CD47 and CD68 expression in breast cancer is associated with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, blood vessel invasion, detection mode, and prognosis. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 9(3), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjp2.309 (2023). Epub 2023 Jan 4.

Yuan, J. et al. High expression of CD47 in triple negative breast cancer is associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis. Oncol. Lett. 18(3), 3249–3255. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2019.10618 (2019). Epub 2019 Jul 15.

Yu, L. et al. Significance of CD47 and its association with tumor immune microenvironment heterogeneity in ovarian cancer. Front. Immunol. 12, 768115 (2021).

Logtenberg, M. E. W., Scheeren, F. A. & Schumacher, T. N. The CD47-SIRPaimmune checkpoint. Immunity 52(5), 742–752 (2020).

Morrissey, M. A., Kern, N. & Vale, R. D. CD47 ligation repositions the inhibitory receptor SIRPA to suppress integrin activation and phagocytosis. Immunity 56(9), 2172 (2023).

Kaur, S. B. & Pal-Nath, S. M. Functions of thrombospondin-1 in the tumor microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(9), 4570 (2021).

Li, J. & Ravetch, J. V. Inhibitory Fcγ receptor engagement drives adjuvant and antitumor activities of agonistic CD40 antibodies. Science 333(6045), 1030–1034 (2011).

Chen, D. S. & Mellman, I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer–immune set point. Nature 541(7637), 321–330 (2017).

Schmid, P. et al. Atezolizumab and Nab-Paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379(22), 2108–2121 (2018).

Emens, L. A. et al. IMpassion130: efficacy in immune biomarker subgroups from the phase III study of atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel vs placebo + nab-paclitaxel in previously untreated advanced triple-negative breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 30(5), v858–859 (2019).

Miles, D. W. et al. Primary results from IMpassion131, a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized phase III trial of first-line paclitaxel ± atezolizumab in locally advanced/metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 31(10), 1418–1427 (2020).

Barclay, A. N. & Van den Berg, T. K. The interaction between sig nal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPalpha) and CD47: structure, function, and therapeutic target. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32, 25–50 (2014).

Chan, K. S. et al. Identification, molecular characterization, clinical prognosis, and therapeutic targeting of human bladder tumor-initiating cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 106(33), 14016–14021 (2009).

Majeti, R. et al. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell 138(2), 286–299 (2009).

Jiang, H. et al. CD47 is ex pressed abnormally on hematopoietic cells in myelodysplastic syndrome. Leuk. Res. (2013).

Chao, M. P. et al. Anti- CD47 antibody synergizes with rituximab to promote phagocytosis and eradicate non-hodgkin. Lymphoma Cell. 142(5), 699–713 (2010).

Chao, M. P. et al. Therapeutic antibody targeting of CD47 eliminates human acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 71(4), 1374–1384 (2011).

Chao, M. P. & Weissman, I. L. The CD47-SIRPalpha pathway in cancer immune evasion and potential therapeutic implications. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24(2), 225–232 (2012).

Edris, B. et al. Antibody therapy targeting the CD47 protein is effective in a model of aggressive metastatic leiomyosarcoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 109(17), 6656–6661 (2012).

Couzin-Frankel, J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer Immunotherapy Sci. 342(6165), 1432–1433 (2013).

Medzhitov, R. et al. Decoding the patterns of self and nonself by the innate immune system. Science 296(5566), 298–300. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1068883 (2002).

Feng, M. et al. Phagocytosis checkpoints as new targets for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 19(10), 568–586. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-019-0183-z (2019).

Sliwkowski, M. X. et al. Antibody therapeutics in cancer. Science 341(6151), 1192–1198. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1241145 (2013).

Scott, A. M. et al. Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 12(4), 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3236 (2012).

Chu, C. C. et al. Antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis is responsible for efficacy of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Immunol. 200(1 suppl), 564 (2018).

Oldenborg, P. A. et al. Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Science 288(5473), 2051–2054. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.288.5473.2051 (2000).

Willingham, S. B. et al. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 109(17), 6662–6667. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1121623109 (2012).

Majeti, R. et al. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell 138(2), 286–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.045 (2009).

Weiskopf, K. et al. Engineered SIRPα variants as immunotherapeutic adjuvants to anticancer antibodies. Science 341(6141), 88–91. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1238856 (2013).

Theruvath, J. et al. Anti-GD2 synergizes with CD47 blockade to mediate tumor eradication. Nat. Med. 28(2), 333–344. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01625-x (2022).

Bian, Z. et al. Intratumoral SIRPα-deficient macrophages activate tumor antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells under radiotherapy. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20314-w (2021).

Advani, R. et al. CD47 blockade by Hu5F9-G4 and Rituximab in non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl. J. Med. 379(18), 1711–1721. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1807315 (2018).

Kharitonenkov, A. et al. A family of proteins that inhibit signalling through tyrosine kinase receptors. Nature 386(6621), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1038/386181a0 (1997).

Stofega, M. R. et al. Growth hormone regulation of SIRP and SHP-2 tyrosyl phosphorylation and association. J. Biol. Chem. 273(12), 7112–7117. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.273.12.7112 (1998).

Liu, Y. et al. STING,a promising target for small molecular immune modulator: a review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 211, 113113 (2021).

Cui, X. et al. STING modulators: predictive sig-nificance in drug discovery. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 182, 111591 (2019).

Margolis SR & Wilson SC Vance RE. Evolutionary origins of cGAS-STING signaling. Trends Immunol. 38, 733–743 (2017).

van Gent, D. C., Hoeijmakers, J. H. & Kanaar, R. Chromosomal stability and the DNA double-stranded break connection. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 196–206 (2001).

Liu, X. et al. CD47 blockade triggers T cell-mediated destruction of immunogenic tumors. Nat. Med. 21(10), 1209–1215 (2015).

Xu, M. M. et al. Dendritic cells but not macrophages sense tumor mitochondrial DNA for cross-priming through cGAS-STING signaling and benefit from PD-L1 checkpoint blockade. Cell. Rep. 21(6), 1219–1231 (2017).

Funding

Hebei Provincial Health Commission research fund project(Fund number: 20221360).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Y.K contributed to conception and design of the study.D.Y.K and Y.Z.C organized the database. Y.J.Y, F.Y and Z.K.L performed the statistical analysis. D.X.S, X.H.L and J.Z wrote the first draft of the manuscript.All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kong, D., Chen, Y., Yin, Y. et al. PD-L1 monoclonal antibody alleviated MI injury of left ventricular function via modulating CD47/SHP2/SIRPα/SYK/FcγR signalings in tumor associated macrophages. Sci Rep 15, 2303 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85065-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85065-w