Abstract

Objectives The rising incidence of sarcopenia and osteoporosis, conditions closely linked to natural aging and frequently occurring together, may have varying impacts on prognosis. The purpose of this research is to use the NHANES database to explore how sarcopenia and osteoporosis may impact all-cause mortality and to assess whether there is an additive effect of these two conditions. Methods Individuals in this research were categorized into four groups depending on whether they had sarcopenia or osteoporosis. This study employed survival curves, Cox regression analyses, and restricted cubic splines, encompassing subgroup and sensitivity analyses, to explore the relationship between sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and all-cause mortality. Results Findings from the study revealed that participants suffering from both sarcopenia and osteoporosis exhibited the lowest survival rates. After adjusting for all potential factors, individuals diagnosed with sarcopenia alone had a 45% higher chance of experiencing all-cause mortality, while those with osteoporosis alone faced a 32% increased risk of all-cause mortality. Furthermore, individuals with both sarcopenia and osteoporosis had a 282% higher risk of all-cause mortality compared to those without either condition. The relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) between sarcopenia and osteoporosis was 4.48 [95% CI: 1.98–8.08], the attributable proportion due to interaction (AP) was 0.66 [95% CI: 0.38–0.79], and the synergy index (S) was 4.4 [95% CI: 1.9–10.2]. Conclusions This indicates that the combination of sarcopenia and osteoporosis may have an additive effect on all-cause mortality, leading to an increased likelihood of death in individuals with both ailments. This study was to emphasize the importance of prevention over treatment for osteoporosis and sarcopenia to reduce the risk of death in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sarcopenia (SP) is a muscular systemic disease with widespread, progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength1. This disease can cause patients to suffer from progressive muscle atrophy, loss of physical ability, reduced quality of life, falls, and even life-threatening situations2. Osteoporosis (OP), which is associated with decreased bone density and the destruction of bone tissue microstructure, increases bone susceptibility, increasing the probability of fracture in the bones3. The incidence of sarcopenia and osteoporosis is an important public health problem in both developed and developing countries4.

Aging diseases (such as sarcopenia and osteoporosis) are attracting more and more attention as the population ages. There is an anatomical and functional connection between muscle and bone as components of the motor system5. As an age-dependent senile syndrome, sarcopenia can eventually involve multiple organs throughout the body, increase the risk of falls and fractures, affect the body’s metabolism, and increase the risk of diseases such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes6,7. Similarly, osteoporosis imposes significant burdens and restrictions on the individual in the form of decreased bone strength, susceptibility to fractures, and so on8,9. Recent research has consistently uncovered a correlation between sarcopenia and osteoporosis, which may show a causal relationship in their development due to the gradual aging of the organism and the close connection between the musculoskeletal system10,11,12,13.

A particular concern in the context of aging is the possible link between sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and mortality risk. As a co-morbidity, osteoporosis and sarcopenia have been addressed in some original papers14, clinical statements15, and guidelines16 called “osteosarcopenia (OS),” but it is not clear whether the co-existence of sarcopenia and osteoporosis increases their respective prognostic impacts on the patient’s prognosis, and therefore our research objective was to determine the presence of an additive effect on all-cause mortality arising from the coexistence of sarcopenia and osteoporosis. Understanding the potential synergistic effects between sarcopenia and osteoporosis is essential for devising effective prevention and treatment strategies, particularly in the context of an aging population. Such insights are vital for optimizing resource allocation, alleviating healthcare system strain, and enhancing the quality of life for older people. Our study aims to provide a robust scientific foundation by comprehensively examining the interaction between sarcopenia and osteoporosis and its influence on all-cause mortality. This research is expected to offer valuable contributions to the field of musculoskeletal health and inform public health policymakers on how to better allocate resources to meet the health needs of aging communities.

By addressing this gap in literature, our work not only advances scientific knowledge but also holds significant implications for enhancing the health and well-being of older people. We anticipate that the findings of this study will shed new light on clinical management approaches and public health interventions for sarcopenia and osteoporosis.

Methods

Study population

Data for this study were collected from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database, a representative national cross-sectional survey administered by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The survey employs a complex sampling method to represent the U.S. population and yields health and nutrition data for the non-institutionalized civilian populace. This is a comprehensive probabilistic survey, targeting household representatives from the non-institutional civilian population of the United States, executed annually in a biennial cycle. Specifically, data from three cycles (2005–2006, 2013–2014, and 2017–2018) were retrospectively analyzed due to the inclusion of skeletal muscle mass testing of the extremities and bone mineral density testing only in these cycles. The Research Ethics Review Committee of NCHS ensures that informed consent is duly obtained from all participants.

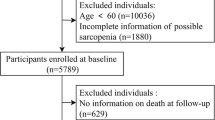

The cohort study encompassed 16,317 participants aged 20 and above, all of whom were subjected to a body composition evaluation via whole-body dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans. Sarcopenia was defined using appendicular lean mass (ALM) and shoeless height, with the criteria set by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) as ALM (kg)/height(m)2 < 7.26 kg/m2 for males and ALM (kg)/height(m)2 < 5.45 kg/m2for females17,18,19,20. Bone mineral density (BMD) was assessed through dual-energy X-ray bone densitometry in the study participants. Osteoporosis was determined according to the criteria established by the World Health Organization (WHO), which defines osteoporosis as a BMD of the femoral neck that is equal to or less than 2.5 standard deviations from the mean BMD of young individuals of the same gender. The exclusion criteria for the study included individuals without a diagnosis of sarcopenia (n = 6681) or osteoporosis (n = 4414), as well as 7 participants who were lost to follow-up and 158 participants with incomplete data on covariates. Ultimately, a total of 5057 participants were included in the retrospective analysis (Fig. 1).

Covariates

Covariates selected for inclusion in this study, based on previous research and guidance from clinical professionals, were age, body mass index (BMI), height, gender, marital status, race, education levels, poverty-to-income ratio (PIR), smoking status, and alcohol consumption. In addition, certain chronic conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, stroke, heart failure, cancer, and arthritis, were included in this study6,10,11,16,21,22. For marital status, participants were categorized into three groups: never married, married/cohabiting, and widowed/divorced/separated. Individuals who had consumed fewer than 100 cigarettes previously were classified as nonsmokers. Participants were classified as smokers based on their smoking status if they had consumed at least 100 cigarettes in the past. For alcohol consumption, participants were categorized as non-drinkers, moderate drinkers, and heavy drinkers. Non-drinkers have never consumed alcohol in their lives. Moderate drinkers were defined as those who consumed less than or equal to 2 drinks per day as men and who consumed less than or equal to 1 drink per day as women. Heavy drinkers were defined as more than 2 drinks per day for men and more than 1 drink per day for women. The PIR was categorized into three groups: low income (PIR ≤ 1.30), middle income (1.31 < PIR < 3.49), and high income (PIR ≥ 3.50), where a higher PIR indicates more favorable economic circumstances. Education levels were categorized as below high school or equivalent; high school graduate or equivalent; and college and above. Given the impact of nutritional status on sarcopenia, BMI was included in the study as one of the measures. Anthropometric measurements were conducted in accordance with standard protocols. Standing height (cm) was gauged using a wall-mounted stadiometer, while weight was determined using a digital scale with a precision of 0.1 kg and a maximum capacity of 150 kg. BMI was computed using the formula: weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m2). Comprehensive guidance on the interpretation, measurement, and calculation of each variable is available on the original website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.

All-cause mortality and follow-up

The outcome indicator utilized in this study was all-cause mortality within the specific disease population. The mortality status of the study participants was determined by linking death certificate data from the National Death Index to NHANES through a probabilistic matching process. All-cause mortality was operationally defined as death resulting from any cause, with specific causes of death encompassing conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, respiratory diseases, malignant neoplasms, Alzheimer’s disease, nephropathy-related diseases, and accidental death. Follow-up for the study was calculated from the NHANES 2005–2006, 2013–2014, and 2017–2018 examination dates until the last known date of alive or censored to 31 December 2019.

Statistical analysis

Given the intricate and hierarchical sampling methodology employed by NHANES, which incorporates multistage, stratification, and clustering techniques, it is imperative to utilize suitable sample weights to account for selection bias and ensure the findings accurately reflect the demographics of the broader United States population. As a result, we utilized the prescribed NHANES weighting methodology to calculate weights specific to each group. Continuous variables are depicted as means (with standard errors), and categorical variables are depicted as frequencies (with percentages). Baseline characteristics were evaluated using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical ones.

To evaluate the risk of all-cause mortality among individuals with sarcopenia, osteoporosis, or both conditions compared to those without either condition, the statistical significance of observed differences was determined through a log-rank test utilizing Kaplan-Meier survival analysis curves. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the risk of all-cause mortality were calculated using weighted Cox regression models that accounted for multiple variables. The first model described the unadjusted connections. The second model was adjusted for gender, age, height, BMI, marital status, education, race, and PIR. The third model was adjusted for gender, age, height, BMI, marital status, education, PIR, race, smoking, alcohol, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, heart failure, cancer, and arthritis. These models aimed to control potential cofounders and provide a more accurate representation of the relationship between the variables under study and mortality outcomes. The study examined the non-linear association between age, BMI, and patient all-cause mortality through restricted cubic splines (RCS) analysis. Additionally, stratified modeling analysis was conducted across various subgroups (gender, PIR, smoking, alcohol, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, heart failure, cancer, and arthritis) to evaluate differences between these groups. Furthermore, the interaction effect of sarcopenia and osteoporosis on the risk of all-cause mortality was assessed to determine if the additive effect of these factors exceeded the sum of their individual effects. The study analyzed additive interactions by assessing RERI, AP, S, and their 95% CI to investigate if there was an additive effect of sarcopenia and osteoporosis. When RERI as well as AP were > 0 and the CI did not include 0, and S > 1 and the CI did not include 1, it indicated that there was an interaction, and it was cooperative. To mitigate the potential for reverse causality confounding our results and to affirm the robustness of our findings, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. This analysis involved the systematic exclusion of participants who experienced death within the first year of follow-up.

All data was analyzed using R Studio software (version 4.3.3). In all tests, P < 0.05 on both sides was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A flowchart illustrating the screening process of study participants was presented (Fig. 1). A total of 5,057 patients were considered eligible for the study. According to their disease condition, we categorized the participants into four groups: OP-/SP- (n = 4155), OP-/SP+ (n = 287), OP+/SP- (n = 495), and OP+/SP+ (n = 120). Baseline characteristics varied among the exposure groups (Table 1). There were no statistically significant variances in education level or the presence of combined hypertension, diabetes, or heart failure across all groups. Individuals in the sarcopenia group were more prone to having arthritis in combination with other conditions, whereas those in the osteoporosis group were the tallest, had a higher percentage of females, a greater number of non-Hispanic whites, and a lower number of non-Hispanic blacks compared to other groups. Compared to the other groups, the group with sarcopenia and osteoporosis exhibited several distinct demographic and health-related characteristics, including the oldest age, the lowest BMI, a higher proportion of females, an increased prevalence of individuals living alone, a greater incidence of poverty and lower income levels, higher rates of smoking, an elevated likelihood of comorbidities such as stroke and cancer, and the highest all-cause mortality rate (OP-/SP-: 4.31% vs. OP-/SP+: 7.60% vs. OP+/SP-: 7.08% vs. OP+/SP+: 28.65%).

Associations with all-cause mortality

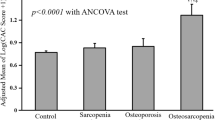

Findings from the study revealed that participants suffering from both sarcopenia and osteoporosis exhibited the lowest survival rates. Further analysis using Kaplan-Meier survival curves indicated that the group without sarcopenia or osteoporosis demonstrated the most favorable survival outcomes. This was followed by those with only sarcopenia, followed by individuals with solely osteoporosis, and ultimately, the cohort afflicted with both conditions experienced the poorest survival prospects. (P-log rank < 0.0001, Fig. 2). Following this, Cox regression models were developed for additional analysis. In all models, individuals with sarcopenia alone, osteoporosis alone, and both sarcopenia and osteoporosis exhibited a heightened risk of all-cause mortality compared to those without sarcopenia and osteoporosis (Table 2). After adjusting for multiple variables, the correlation diminished yet persisted as statistically significant. In fully adjusted models, compared with the population without sarcopenia and osteoporosis, there was a 45% increased risk of all-cause mortality in the sarcopenia alone population (HR: 1.45; 95% CI: 1.06–1.84), a 32% increased risk of all-cause mortality in the osteoporosis alone population (HR: 1.32; 95% CI: 1.13–1.96), and a 282% increased risk of all-cause mortality in the sarcopenia and osteoporosis population (HR: 3.82; 95% CI: 1.71–7.53). The correlations across all models demonstrated a consistent pattern, with the largest effect in the sarcopenia and osteoporosis populations and the smallest effect in the osteoporosis alone population.

Furthermore, the smooth fit curves demonstrated a non-linear relationship between age, BMI, and the likelihood of patient mortality following control for all potential confounding variables (Fig. 3).

Additive interactions

The RERI for the interaction between sarcopenia and osteoporosis was 4.48 [95% CI: 1.98–8.08], AP was 0.66 [95% CI: 0.38–0.79], and S was 4.4 [95% CI: 1.9–10.2]. These results suggest a significant interaction on the additive scale, indicating an additive effect. Consequently, the risk of all-cause mortality associated with the co-occurrence of sarcopenia and osteoporosis surpassed the combined risks of each condition individually (Table 2).

Subgroup analysis

Stratifying participants by gender, smoking, PIR, hypertension, stroke, heart failure, cancer, and arthritis, compared to individuals devoid of both sarcopenia and osteoporosis, the relative mortality risk was markedly increased in those afflicted with both conditions. When analyzing the data by alcohol consumption and diabetes status, no statistically significant difference in mortality risk was observed between nondrinkers and individuals with diabetes (Fig. 4).

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis produced findings in alignment with those depicted by the Kaplan-Meier survival curves. These curves showed that individuals free from both sarcopenia and osteoporosis had the most favorable survival outcomes. Subsequently, survival rates decreased in a stepwise fashion for those with only sarcopenia, followed by those with only osteoporosis, and were the least for individuals suffering from both conditions (P-log rank < 0.0001, Figure S1). In comparison to patients devoid of sarcopenia and osteoporosis, the risk of all-cause mortality was elevated by 28% in individuals with sarcopenia alone (HR: 1.28; 95% CI: 0.96–1.78), by 12% in individuals with osteoporosis alone (HR: 1.12; 95% CI: 0.92–1.61), and significantly surged to 322% in patients suffering from both conditions (HR: 4.22; 95% CI: 1.73–8.40). An additive effect was observed in the interaction between sarcopenia and osteoporosis, indicated by a RERI of 4.43 [95% CI: 1.95–8.05], an AP of 0.68 [95% CI: 0.39–0.80], and a S of 4.97 [95% CI: 1.92–12.89] (Table S1).

Discussion

In this extensive cohort study conducted in America, our findings substantiated the association between sarcopenia and osteoporosis and an increased risk of all-cause mortality. Furthermore, our analysis revealed a cooperative interaction of sarcopenia and osteoporosis on all-cause mortality that surpassed the anticipated impact of each condition individually, even after controlling for multiple confounding variables. These results remained consistent across various subgroups stratified by gender, smoking, alcohol, PIR, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, heart failure, cancer, and arthritis. This retrospective cohort study represents the first known investigation into the cooperative interaction of sarcopenia and osteoporosis on all-cause mortality within the United States population.

Sarcopenia and osteoporosis are significant health concerns on a global scale due to their widespread occurrence in the general population, particularly among older individuals5. While sarcopenia is not traditionally identified as a complication of osteoporosis, recent research indicates that the incidence of sarcopenia is notably higher in individuals with osteoporosis compared to those without the condition23. Previous research has equally determined that sarcopenia directly impacts bone strength and metabolism, resulting in a gradual decline of bone microarchitecture and ultimately raising the likelihood of osteoporosis development13. Both sarcopenia and osteoporosis are linked to serious morbidity, increased mortality rates, and elevated societal expenses because of their long-term effects4. As a result of osteoporosis, patients suffer from serious muscle loss and weakness24. Studies have revealed that sarcopenia is associated with increased fracture risk25. This underscores the importance of co-managing sarcopenia and osteoporosis. A two-way Mendelian randomization study revealed a significant association between sarcopenia and osteoporosis, indicating that they may act as reciprocal risk factors26. However, research into the cooperative interaction of sarcopenia and osteoporosis with all-cause mortality remains scarce. Our study demonstrated that the risk of all-cause mortality was elevated in cases where sarcopenia and osteoporosis coexisted compared to when they were present individually. Furthermore, additive interaction modeling indicated a cooperative interaction of sarcopenia and osteoporosis on all-cause mortality. Therefore, the intricate relationship between sarcopenia and osteoporosis warrants further investigation.

There may exist shared mechanisms between the two diseases that contribute to an unfavorable prognosis, with advancing age and lower BMI potentially playing crucial roles8,27,28. Our study identified a non-linear correlation between age, BMI, and mortality risk among patients, a phenomenon not extensively documented in current literature. The elevated mortality risk with increasing age may be attributed to the natural decline in physiological functions, the cumulative impact of chronic diseases, and a compromised immune system29. Notably, the lowest mortality risk was observed when BMI was within the range of 22–27, aligning with the notion that a moderate BMI reflects optimal nutritional status and muscle mass, which are linked to better physical performance and a reduced mortality risk13,29. BMI values outside this range were associated with a heightened mortality risk. Low BMI correlates with several factors, including malnutrition, leading to immune dysfunction30; a diminished metabolic rate, resulting in inefficient energy utilization31; and reduced muscle mass, causing weakness, impaired daily activity performance, and decreased bone density, thereby increasing the risk of falls and fractures32, all of which augment the risk of death. Conversely, a high BMI can precipitate various diseases such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases, collectively escalating the mortality risk33. Additionally, a high BMI may coincide with mental health issues and unhealthy lifestyles, further amplifying the risk of death. High BMI also implies a higher body fat percentage, increasing bodily strain and adversely affecting muscle and bone quality, potentially leading to musculoskeletal diseases, impairing quality of life, and possibly increasing mortality34. This study offers a novel perspective for identifying risk factors in patients with co-occurring sarcopenia and osteoporosis. The implications of our findings could inform public health policies, especially in formulating weight management guidelines and preventive strategies.

The presence of a shared pathophysiologic mechanism between these conditions underscores a close interconnection between the two diseases27. Our research indicates potential interactive biological mechanisms between sarcopenia and osteoporosis that may elevate mortality risks. Firstly, the biomechanical interplay between muscles and bones is evident; muscle contractions impose forces on bones via tendons, influencing osteoblast and osteoclast activities, which are crucial for bone remodeling and density. Conversely, osteoporotic bone density reduction may impair muscle strength due to the essential role of bone mass in supporting muscular function35. Secondly, both conditions share inflammatory and hormonal pathways. Age-related chronic inflammation can disrupt muscle protein synthesis and catabolism, as well as bone metabolism, with cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 being particularly influential36. Decreased sexual hormones, such as estrogen and testosterone, are linked to reduced muscle and bone health37,38. Nutritional components, including protein, vitamin D, and calcium, are vital for muscle and bone integrity; deficiencies can lead to muscle wasting and osteopenia, while optimal nutrition can ameliorate these conditions39. Lastly, endocrine interactions between muscles and bones, mediated by factors such as IGF-1, TGF-β, and BMPs, regulate bone metabolism and muscle growth40,41,42,43. In conclusion, the complex interplay between sarcopenia and osteoporosis, spanning biomechanical, inflammatory, hormonal, nutritional, and genetic mechanisms, could increase mortality by compromising muscle strength and bone density, raising fall and fracture risks, and precipitating further complications. Thus, integrated prevention and management strategies for these conditions must consider these multifaceted interactions.

Current pharmacologic interventions for the co-morbidities of sarcopenia and osteoporosis are limited, and their effectiveness remains uncertain4. Therefore, prioritizing preventive strategies over therapeutic approaches is essential. Targeting high-risk populations, such as older people and individuals with a history of sarcopenia or osteoporosis, necessitates regular assessments of bone density and muscle mass. It is crucial to encourage patients to engage in individualized physical activity programs, including both aerobic and resistance training, to enhance muscle strength and bone health. Nutrition plays a vital role in the prevention and treatment of sarcopenia and osteoporosis; thus, increasing the intake of high-quality protein and ensuring adequate vitamin D and calcium levels are imperative for supporting muscle and bone health. Establishing a multidisciplinary team comprising clinicians, dietitians, physical therapists, and nurses is essential for delivering a comprehensive management program. Regular monitoring of patients’ muscle mass, function, bone density, and relevant nutritional indicators is necessary to evaluate treatment effectiveness and make timely adjustments to the management plan. By implementing these comprehensive preventive and intervention measures, we can more effectively manage sarcopenia and osteoporosis, thereby reducing patient mortality. We anticipate further studies that will provide additional pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions, as well as innovative diagnostic tools for sarcopenia and osteoporosis.

Our study acknowledges several limitations. Firstly, as a retrospective analysis of the NHANES database, our study could not entirely account for the impact of unknown confounders on all-cause mortality, despite adjusting for multiple potential factors. Secondly, the current NHANES database permits assessment of sarcopenia based on muscle mass alone; future studies should incorporate evaluations of muscle strength and physical performance. Lastly, our findings, derived from a specific U.S. population, require validation across diverse populations. Consequently, we intend to execute multi-center clinical trials in China to enhance the generalizability and applicability of our results. Such studies will aid in a more comprehensive understanding of sarcopenia and osteoporosis pathogenesis and treatment efficacy across different populations. They will also facilitate the development of novel biomarkers and diagnostic tools for early and precise identification of sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and their co-morbidities. Additionally, more randomized controlled trials are needed to assess the efficacy and safety of existing pharmaceuticals, nutritional supplements, and non-pharmacological interventions such as exercise and physical therapy. Future research should also examine the influence of socioeconomic status on pathogenesis, treatment, and prognosis of these conditions and explore social policy interventions to mitigate these effects. Given the higher prevalence of sarcopenia and osteoporosis among the older people, special attention should be paid to their unique needs, including optimizing treatment regimens and enhancing quality of life. Long-term follow-up studies are essential to assess the long-term health impacts, including mortality, quality of life, and healthcare resource utilization.

Conclusions

A notable interplay exists between sarcopenia and osteoporosis, which precipitates an elevated risk for all-cause mortality. The results underscore the critical need for effective management and preventive strategies to mitigate the mortality risk among individuals with the co-existing conditions of sarcopenia and osteoporosis.

Data availability

All data are available as publicly accessible datasets through NHANES: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.

References

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. & Sayer, A. A. Sarcopenia Lancet 393, 2636–2646 (2019).

Papadopoulou, S. & Sarcopenia A contemporary health problem among older adult populations. Nutrients 12, 1293 (2020).

Fan, Y. et al. Sex- and Age-Specific prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: sampling survey. JMIR Public. Health Surveill. 10, e48947 (2024).

Gielen, E., Dupont, J., Dejaeger, M. & Laurent, M. R. Sarcopenia, osteoporosis and frailty. Metabolism 145, 155638 (2023).

Kirk, B., Zanker, J. & Duque, G. Osteosarcopenia: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment—facts and numbers. J. cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 11, 609–618 (2020).

Huang, W. et al. Association of metabolic syndrome and sarcopenia with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a prospective cohort study based on the NHANES. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1346669 (2024).

Kim, S., Kim, S. & Hong, K. H. Association of combining diet and physical activity on sarcopenia and obesity in elderly Koreans with diabetes. Nutrients 16, 964 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Alpha-ketoglutarate ameliorates age-related osteoporosis via regulating histone methylations. Nat. Commun. 11, 5596 (2020).

Smith, C., Sim, M., Dalla Via, J., Levinger, I. & Duque, G. The interconnection between muscle and bone: A common clinical management pathway. Calcif Tissue Int. 114, 24–37 (2023).

Hoang, D. K. et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for sarcopenia in community-dwelling people: the Vietnam osteoporosis study. J. cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 15, 380–386 (2024).

Osawa, Y. et al. Longitudinal association between muscle and bone loss: results of US and Japanese cohort studies. J. cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 15, 746–755 (2024).

Vendrami, C. et al. Muscle parameters in fragility fracture risk prediction in older adults: A scoping review. J. cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 15, 477–500 (2024).

Genest, F., Rak, D., Bätz, E., Ott, K. & Seefried, L. Sarcopenia and Malnutrition Screening in Female Osteoporosis Patients—A Cross-Sectional Study. JCM 10, 2344 (2021).

Salvadori, L. et al. Equisetum arvense standardized dried extract hinders age-related osteosarcopenia. Biomed. Pharmacother. 174, 116517 (2024).

Huang, R. et al. Lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet is inversely associated with the osteosarcopenia in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 24, 332 (2024).

Kirk, B., Miller, S., Zanker, J. & Duque, G. A clinical guide to the pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of osteosarcopenia. Maturitas 140, 27–33 (2020).

Huang, H. The relationship between serum lipid with sarcopenia: results from the NHANES 2011–2018 and bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Exp. Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2024.112560 (2024).

Geng, J. et al. Dietary inflammatory potential and risk of sarcopenia: data from National health and nutrition examination surveys. Aging 13, 1913–1928 (2021).

Perez-Lasierra, J. L., Casajus, J. A., González-Agüero, A. & Moreno-Franco, B. Association of physical activity levels and prevalence of major degenerative diseases: evidence from the National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 1999–2018. Exp. Gerontol. 158, 111656 (2022).

Golabi, P. Contribution of sarcopenia and physical inactivity to mortality in people with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. 2, (2020).

Karanth, S. D. et al. Inflammation in relation to sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity among older adults living with chronic comorbidities: results from the National health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2006. Nutrients 13, 3957 (2021).

Li, W., Xie, S., Zhong, S. & Lan, L. The synergistic effect of diabetes mellitus and osteoporosis on the all-cause mortality: a cohort study of an American population. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1308574 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Association between advanced glycation end products and sarcopenia: the mediating role of osteoporosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 109, e1105–e1116 (2024).

Dudinskaya, E. N. et al. The association of osteoporosis and geriatric syndromes in the elderly: data from the Russian epidemiological study EVKALIPT. Arch. Osteoporos. 18, 30 (2023).

Jauffret, C. et al. Association between sarcopenia and fracture risk in a population from the UK biobank database. J. Bone Miner. Res. 38, 1422–1434 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia-related traits: A bi-directional Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 975647 (2022).

Sasako, T. et al. Deletion of skeletal muscle Akt1/2 causes osteosarcopenia and reduces lifespan in mice. Nat. Commun. 13, 5655 (2022).

Guo, M. et al. Irisin ameliorates age-associated sarcopenia and metabolic dysfunction. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 14, 391–405 (2023).

Kobayashi, K. et al. Epidemiology and effect on physical function of osteosarcopenia in community-dwelling elderly people in Japan. Mod. Rheumatol. 30, 592–597 (2020).

Kiss, N. et al. Low muscle mass, malnutrition, sarcopenia, and associations with survival in adults with cancer in the UK biobank cohort. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13256

Wang, X. et al. Correlation between mild cognitive impairment and sarcopenia: the prospective role of lipids and basal metabolic rate in the link. (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Global epidemiological features and impact of osteosarcopenia: A comprehensive meta-analysis and systematic review. J. cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 15, 8–20 (2024).

Du, Y., Oh, C. & No, J. Associations between sarcopenia and metabolic risk factors: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. JOMES 27, 175–185 (2018).

Chen, N., Fong, D. Y. T. & Wong, J. Y. H. Health and economic outcomes associated with musculoskeletal disorders attributable to high body mass index in 192 countries and territories in 2019. JAMA Netw. Open. 6, e2250674 (2023).

Xu, N. et al. Therapeutic effects of mechanical Stress-Induced C2C12-Derived exosomes on Glucocorticoid-Induced osteoporosis through miR-92a-3p/PTEN/AKT signaling pathway. IJN 18, 7583–7603 (2023).

Yılmaz, D., Mathavan, N., Wehrle, E., Kuhn, G. A. & Müller, R. Mouse models of accelerated aging in musculoskeletal research for assessing frailty, sarcopenia, and osteoporosis – A review. Ageing Res. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.102118 (2024).

Alonso-Puyo, J. et al. Experimental models as a tool for research on sarcopenia: A narrative review. Ageing Res. Rev. 101, 102534 (2024).

Yoon, D. S. et al. Downregulation of the RNA-binding protein PUM2 facilitates MSC-driven bone regeneration and prevents OVX-induced bone loss. J. Biomed. Sci. 30, 26 (2023).

Thomson, C. A. et al. Long-Term effect of randomization to calcium and vitamin D supplementation on health in older women: postintervention Follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 177, 428–438 (2024).

Morales-Jiménez, C. et al. Mechanical disturbance of osteoclasts induces ATP release that leads to protein synthesis in skeletal muscle through an Akt-mTOR signaling pathway. IJMS 23, 9444 (2022).

Suh, J. et al. GDF11 promotes osteogenesis as opposed to MSTN, and follistatin, a MSTN/GDF11 inhibitor, increases muscle mass but weakens bone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117, 4910–4920 (2020).

Wang, Y., Liu, S., Yan, Y., Li, S. & Tong, H. SPARCL1 promotes C2C12 cell differentiation via BMP7-mediated BMP/TGF-β cell signaling pathway. Cell. Death Dis. 10, 852 (2019).

Mou, K., Chan, S. M. H. & Vlahos, R. Musculoskeletal crosstalk in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbidities: emerging roles and therapeutic potentials. Pharmacol. Ther. 257, 108635 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported in part by the following grants: National Natural Science Foundation of China (82205137, 82274542, 82274615), Guangdong Province Medical Research Fund (A2022001), and the Basic and Applied Basic Research Program of Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (2024 A04 J4332).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Y.L., H.C., and P.Z. wrote a draft of this article. Q.S., Y.Z., and W.Q. performed the analysis. Y.Z., J.H., W.Q., and F.L. prepared figures and tables. H.R., X.J., and G.S. conceived the study design. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by NCHS Ethics Review Board. The portions of this study involving human participants, human materials, or human data were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Informed consent

NHANES is a public dataset and all participants provided a written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Chen, H., Zhang, P. et al. The additive effect of sarcopenia and osteoporosis on all-cause mortality: a cohort analysis in a U.S. population. Sci Rep 15, 43408 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00003-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00003-8