Abstract

The release of flue gases is a widespread environmental issue in mineral processing operations. This flue gas contains several components i.e. CO2, CO, SO2, SO3, NO2, particulate, etc. Previously, trials were conducted on the usage of flue gas for the carbonation of process liquor generated from mineral processing industries at the batch level. Successful results and further modeling via MATLAB 2024 created the scope of further research on continuous trials for carbonation of process liquor. Experiments were conducted with proper arrangement for dipping flue gas into a reactor of approximately 200 L volume. Further analysis was done for Na2CO3, NaHCO3, and NaOH content before and after carbonation trials in batch mode. Modeling was done using MATLAB 2024 software after evaluating rate constants for main chemical reactions. These rate constant values may further be used to design suitable absorber columns on an industrial scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The conversion of carbon dioxide holds promise as a pivotal component in the sustainable and resource-efficient synthesis of chemicals and energy from renewable sources (Quadrelli et al., 2011). CO2 utilization plays a significant role in advancing sustainability, as it enables the synthesis of diverse chemicals, materials, and fuels, thereby offering a sustainable pathway in the long run, mainly when renewable energy sources are employed as the energy input (Song, 2006). A notable enhancement in the carbonation products was observed with the application of microwave energy at reduced gas flow rates and steam rates. Ultimately, a carbonation level of 23% CO2 was achieved (İsmail Tosun, 2020). (Muradov, 2014) assessed current and evolving CO2 utilization technologies based on their technological readiness, market scale, durability of CO2 sequestration, environmental footprint, prospective revenue streams, and capacity for carbon mitigation. The findings (Schmid & Hahn, 2021), indicate that the theoretical carbon dioxide requisition across all examined carbon capture and utilization (CCU) pathways ranges from approximately 234 to 423 million metric tons of CO2 per annum in 2030, with energy carriers constituting the predominant portion, exceeding 75%. The industrial utilization across pre and post-combustion CO2 capture contexts was systematically examined by Gao et al., 2020. Our research is based on the carbonation of alkali solution. Izidoro et al., 2021proved that the valorization of value-added products derived from brine sludge represents a significant stride toward sustainable development within the Chlor-alkali sector. Likewise, (Saravanan et al., 2021) concluded that through various chemical, physical, and biological methodologies, carbon dioxide can undergo conversion into valuable commodities such as fuels and chemicals. Various perspectives on the prospective trajectory of CO2 hydrogenation are delineated by Varvoutis et al., 2022. Theo et al., 2016 concluded that the metallurgical sector is facing significant pressure to diminish CO2 emissions due to escalating environmental apprehensions regarding climate change. Rasul et al., 2014 did research related to carbonation at coal-fired plants. Retention efficiencies ranging from 70 to 97% have been achieved under practical flue gas circumstances in the carbonator reactor by Abanades et al., 2009. Sequestration capabilities vary from 2 to 800 kg of carbon dioxide per metric ton of refuse, contingent upon methodologies, waste composition, and operational parameters as per Baena-Moreno et al., 2023. Absorption efficiencies of 98% and 65% were attained by employing sodium NaOH and Ba(OH)2 respectively by Proaño et al., 2020. Lin et al., 2024 proved that the generation of value-added secondary products is beneficial for enhancing the economic viability of the process. Godin et al., 2021 concluded that the substantial energy expenditure and financial outlay represent the primary impediment to its advancement. Wawrzyńczak, 2022 showcased a case study that employs the research findings of a multinational team formed within the CCS CCU technology for carbon footprint mitigation using bio-adsorbents. Rusanowska et al., 2023demonstrated that technological remedies are user-friendly and cost-effective, with certain solutions additionally considering reagent regeneration. (Rahmanihanzaki & Hemmati, 2022) analyzed and juxtaposed various sources of alkaline solid wastes.

According to the most recent data illustrated in Fig. 1, India accounts for approximately 7% of global carbon dioxide emissions, indicating its substantial role in the global emission landscape. Addressing this issue requires collective responsibility and proactive efforts from individuals to minimize their carbon footprint (Teir et al., 2016). With the continuous rise in population, the demand for natural resources and energy remains critical for technological advancement across nations (Sharma et al., 2023). Managing CO₂ emissions from industrial activities is vital for several key reasons, including mitigating climate change, protecting public health, promoting environmental sustainability, ensuring compliance with regulatory standards, and achieving economic advantages (Rajesh N.V., 2023).

Figure 2 illustrates the motivation pyramid for reducing carbon dioxide emissions across industrial sectors, highlighting the key drivers behind decarbonization initiatives. At the top of the pyramid is climate change mitigation, which represents the most critical and urgent global priority, aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and limit global warming. The next level emphasizes health and air quality, acknowledging the direct impact of CO₂ and associated pollutants on public health. The third layer focuses on sustainability and resource efficiency, promoting the responsible use of natural resources to ensure long-term industrial viability. Environmental stewardship, positioned next, reflects the growing recognition of industries’ responsibility to protect ecosystems and biodiversity. Further down the pyramid, regulatory compliance and risk management underscore the importance of adhering to environmental laws and minimizing operational risks. Finally, the base of the pyramid highlights innovation and economic opportunities, illustrating how CO₂ reduction efforts can drive technological advancements, open new markets, and improve overall economic performance. The structure of the pyramid signifies the layered, yet interconnected, motivations that collectively drive industry-wide efforts toward a low-carbon future.

The boiler is mechanical equipment that is used for steam generation in almost all mineral ore processing plants, chemical plants, cement plants, etc. Several types of fuels are used for the operations of boilers i.e. light diesel oil, rice husk, sugarcane bagasse, coal, etc. These fuels are burned out to raise the temperature of boiler vessels for further boiling of water for steam generation. As per Sharma V. K., 2023; Flue gas is generated after the burning of these fuels. Flue gas is a mixture of several harmful gases which can contaminate the atmosphere if not treated properly. Figure 3 represents the data analysis of CO2 emissions from the year 1750 to 2000.

The main composition of flue gas contains SOx, NOx, COx, particulate matter, etc. as detailed by Rajesh L., 2019. As per International and National Regulatory Board Standards, proper height of stack and composition of flue gas is mandatory to maintain for all factories to obtain operation licenses (T. Sunil, 2024). Our research is based on the beneficial usage 3of this flue gas generated by industries which not only controls environmental pollution but also benefits industries in terms of the production of an important raw material for them (CO2) for the carbonation step.

Materials and methods

Mineral processing for low-grade ore is a challenging task. Several advanced chemical processing techniques are adopted to achieve maximum ore recovery. Reddy TCS, 2021 provided information about the latest research and technical modifications. Leaching is the heart of several low-grade mineral ore processing industries. Based on the characteristics of ore, either acidic or alkali leaching is adopted in many processing plants. For achieving maximum leaching efficiency, either atmospheric or pressurized leaching is followed after successful trials on the pilot scale level (Thamida S.K., 2023). Leaching is the process of extraction of a desired material from solid to liquid with the help of suitable temperature, pressure, reagent, and oxidizing agent. Sodium carbonate is the main reagent used for leaching operations in low-grade mineral ore processing leaching operations. Clarification is being done after leaching for the removal of un-leached solids. After clarification, precipitation of liquor is required for extraction of the desired final product in industries. NaOH is one of the important raw materials used for the precipitation of desired minerals from clarified leach liquor (Thamida S.K., 2022). After precipitation, the final product settles in thickener underflow due to the addition of suitable flocculent as per Siddique et al., 2015. Overflow contains sodium hydroxide which can be further converted to sodium carbonate by the addition of carbon dioxide as mentioned in chemical reaction 1. Carbonation is an important step in the mining and mineral processing industries. It can be defined by chemical reaction 1:

The main objectives of carbonation in the mineral processing industry are as mentioned in Fig. 4:

It is crucial to emphasize that the precise goals of carbonation within the mineral processing sector may differ based on factors such as ore type, intended final product, and operational needs. The parameters governing carbonation; such as temperature, pressure, and carbon dioxide concentration must be meticulously regulated to attain the desired results.

Experimental method

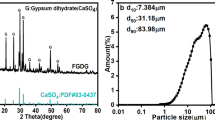

Successful trials of batch mode carbonation experiments were conducted by Rao M.S., 2019 by purging flue gas into a 5 L volume cane. Before implementation at the industrial level, it was considered to evaluate trials on a large scale. The 200 L volume of the continuous reactor was considered for the experimental trials. This continuous reactor was filled with process liquor (Rao M.S., 2019a). Air is essential for the burning of fuel passing through the burner of boilers. Light diesel oil (LDO) fired boiler considered for our experimental trials. Technical specifications of light diesel oil are mentioned in Table 1 (UCIL, 2017) for reference.

After the burning of LDO, flue gas is generated through the stack. The composition of the flue gas evaluated is mentioned in Table 2. This composition represents enough carbon dioxide present in flue gas which can further be used for beneficial purposes (Sharma et al., 2024). As per Aravind et al., 2021, flue gas passes through an air preheater (APH) from one side. From another side atmospheric air passes to increase the inlet temperature of air (Sriharsha P., 2023).

Pump installed at the exhaust side of flue gas from APH. Technical specifications of the installed pump are mentioned in Table 3.

The complete experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Acceptable thresholds of boiler flue gas composition

The permissible limits of boiler flue gas composition in India are regulated by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) and vary depending on the type of industry and the capacity of the boiler (S. Suman, 2022). The permissible limits are stipulated under the Environment (Protection) Act of 1986 and its subsequent amendments, along with industry-specific pollution control regulations. Table 4 presents typical examples of allowable flue gas composition levels from boilers as per Indian standards.

It is crucial to acknowledge that these thresholds may undergo alterations in response to advancing environmental statutes and particular industrial prerequisites. Businesses must adhere to these boundaries and implement requisite actions, such as integrating pollution mitigation apparatus, employing cleaner energy sources, and embracing efficient technologies, to fulfill the designated emission criteria.

Laboratory testing techniques

Assessing the chemical laboratory analysis of Na2CO3, NaHCO3, and NaOH commonly entails evaluating its purity or concentration (Satpati S.K., 2025). Below is a detailed manual outlining the procedure for conducting a fundamental analysis, as referenced in Fig. 6.

Results and discussions

The completion of successful carbonation is evidenced by the depletion of all NaOH during the process of purging flue gas into the process liquor (Thamida S. K., 2025). Table 5 provides a clear illustration of this principle, demonstrating that the quantities of Na2CO3 and NaHCO3 increased steadily over time. These findings signify the satisfactory culmination of reaction 1.

The results from the large-scale batch trials reveal a clear progression in the chemical composition of the process liquor as carbonation time increased from 0 to 120 min. Initially, the liquor contained 13.21 g/L of NaOH and 33.22 g/L of Na₂CO₃, with no detectable NaHCO₃. As carbonation proceeded, a steady decrease in NaOH concentration was observed, dropping to zero by the 120-minute mark. This reduction corresponds with a progressive conversion of NaOH and Na₂CO₃ into NaHCO₃, particularly noticeable between 60 and 120 min. The Na₂CO₃ concentration increased steadily up to 90 min, reaching a peak of 54.91 g/L, before declining to 48.61 g/L at 120 min, likely due to its reaction with CO₂ to form NaHCO₃. The formation of NaHCO₃ became significant only after 90 min, with a final concentration of 7.17 g/L recorded at 120 min. These trends underscore the kinetics of carbonation and indicate that beyond 90 min, the system transitions from carbonate accumulation to bicarbonate formation, marking a shift in the reaction pathway driven by CO₂ saturation and residual alkalinity.

The main chemical reactions held during carbonation trials as per Sreenivas T., 2010 are as follows:

In this study, the quantities of NaHCO₃, Na₂CO₃, and carbon dioxide (CO₂) required for carbonation were estimated based on two key chemical reactions:3] and [4. A solution containing 13.21 g/L of NaOH and 33.22 g/L of Na₂CO₃ was analyzed, yielding molar concentrations of 0.33025 mol/L for NaOH and 0.31302 mol/L for Na₂CO₃. Based on the 1:1 stoichiometry of Reaction3, 0.33025 mol/L of NaHCO₃ (equivalent to 27.74 g/L) is required to fully react with the NaOH present. In parallel, Reaction4 indicates that 0.31302 mol/L of Na₂CO₃ (equivalent to 33.22 g/L) can react with an equal amount of CO₂ and water to produce up to 0.62604 mol/L of NaHCO₃. Therefore, 33.22 g/L of Na₂CO₃ is required for the carbonation trials, matching the existing solution concentration. Additionally, the required amount of CO₂ for full carbonation is 0.33025 mol/L (14.53 g/L), based on its 1:1 molar ratio with NaHCO₃ in Reaction3. These calculations provide a quantitative basis for selecting reagent dosages in carbonation trials, ensuring optimal alkali utilization and CO₂ sequestration efficiency. Figure 7 represents quantities of reagents required for carbonation:

After a specific period, the position of NaHCO3 starts to decrease. At higher temperatures, sodium bicarbonate will also undergo decomposition into sodium carbonate and CO2, according to reaction 2. The addition of bicarbonate to the leach solution serves to prevent the re-precipitation of dissolved minerals through its interaction with hydroxyl ions (Chaturvedi et al., 2021). The precipitation of leached liquor stands as a pivotal stage in mineral processing industries, facilitating the extraction of desired minerals from ore. Concentrated sodium hydroxide finds widespread application across various industries for this very purpose. Following precipitation at the designated temperature and appropriate retention time in tanks, numerous intermediate components are consumed throughout the process. In the context of alkali leaching processes, various salts are employed across multiple stages of chemical processing (Singh A. K., 2014). Post-precipitation, as noted by A.K Suri, 2010, the system retains sodium carbonate, residual sodium hydroxide, and selected minerals. Upon the completion of precipitation reactions, the desired minerals are extracted from the product thickener as underflow, while the overflow contains excess sodium hydroxide. This surplus sodium hydroxide undergoes conversion to sodium carbonate and is subsequently recycled into the chemical process after the introduction of carbon dioxide. Boilers powered by light diesel oil fuel are integral to maintaining optimal temperatures across various chemical processing stages within mineral processing industries, utilizing steam (Sharma et al., 2025). Flue gas, a byproduct of fuel combustion within these boilers, is ultimately emitted through the stack. Our research endeavors focus on evaluating the beneficial utilization of this flue gas by purging it into the process liquor and subsequently recycling it within mineral processing industries, as highlighted by Thamida, 2019. Specific observations about this endeavor are detailed in Fig. 8.

Modeling of chemical reactions using MATLAB 2024

When analyzing the concentrations of Na2CO3, NaHCO3, NaOH, and carbon dioxide, denoted as A, B, C, and D respectively, the equilibrium chemical reaction for the ongoing experiments can be formulated as chemical reaction 3 (with rate constant k1) and chemical reaction 4 (with rate constants k2 for forward and k3 for backward) as explained previously. Considering the rate constant for chemical reaction 1 as ‘k4’, the equations for the rate of reactions are defined as (5), (6) and (7) below:

The concentrations of Na2CO3, NaHCO3, and NaOH were converted from g/L to mol/L using their respective molecular weights. A notable distinction exists between the large tank (200 L) employed in this latest research and the small tank (5 L) utilized in earlier studies by Sharma et al., 2023. Specifically, the small tank maintains a constant concentration of dissolved carbon dioxide in the liquor, denoted as Cs, whereas the large tank experiences high CO2 depletion due to limited liquid gas holding up a large liquid pool reacting with and consuming CO2, which is a result of mass transfer resistance. Consequently, the CO2 concentration in the liquid phase is assumed to increase gradually as a first-order process, described by Eq. 4:

where D(t) = Concentration of CO2 in liquid at time ‘t’.

Cs = Solubility limits of CO2 in liquid = 1.45 g/L, and.

τ = Time constant for CO2 solubilization in the liquid,

It is found by data fitting of concentration vs. time that for Na2CO3, NaHCO3, and NaOH the soluble value of ‘τ’ is ~ 100 min. The values of rate constants at this reaction temperature are found as; k1 = 0.0216 L/g mol minute, k2 = 0.0010 L/g mol minute, k3 = 0.0570 L/g mol minute, k4 = 0.0500 L/g mol minute.

MATLAB 2024 programming for carbonation trial study

Employing MATLAB 2024 Programming for the batch experimentation exploring carbonation, the examination was conducted using the aforementioned chemical equations to ascertain the reaction rate constants ‘k1,’ ‘k2,’ ‘k3’ and ‘k4’ In this context, ‘k1’ signifies the rate constant for chemical reaction 3, while ‘k2’ and ‘k3’ denote the rate constants linked with chemical reaction 4 whereas, rate constant for chemical reaction 1 considered as ‘k4’.

MATLAB 2024 programming for determination of reaction rate ‘k1’ and ‘k3’

clear all.

time (1) = 0;

A (1) = 33.22/105;;

B (1) = 0;

C (1) = 13.21/40;%C (1) = 0.4;

D (1) = 0;

dt = 0.01;

k1 = 0.0216;k1 = 0.0216;

k2 = 0.0040;k2 = 0.001;

k3 = k2*55*1.45/ (1)^2;

k3 = 0.057;k3 = 0.057;

k4 = 0.05;

k5 = 0.01;

Cs = 1.45;

A1 = 0.01;

time (1) = 0;

for i = 1:12000.

D(i + 1) = Cs*(1-exp(-A1*time(i)));

A(i + 1) = A(i) + dt * (-k2*D(i)*A(i) + k3*B(i)^2 + k1*B(i)*C(i) + k4*0.5*D(i)*C(i));

B(i + 1) = B(i) + dt*(2*k2*D(i)*A(i)-k3*B(i)^2-k1*B(i)*C(i)) ;

C(i + 1) = C(i) + dt*( -k1* B(i) *C(i)-k4*D(i)*C(i));

%D(i + 1) = D(i) + dt * (A1*(Cs - D(i)) );

% dt = abs(0.1/ (A1*(Cs - D(i)) ));

time(i + 1) = time(i) + dt;

end.

figure(1).

plot(time, A).

hold on.

plot(time, B).

plot(time, C).

t_expt = [0 30 60 90 120];

A_expt=[33.22 39.68 46.78 54.91 48.61]/105;

B_expt=[0 0 0 0 7.17]/84;

C_expt=[13.21 10.54 4.46 2.01 0]/40;

plot(t_expt, A_expt, ‘o’).

plot(t_expt, B_expt, ‘sq’).

plot(t_expt, C_expt, ‘^’).

legend(‘Na_2CO_3’, ‘NaHCO_3’, ‘NaOH’, ‘Na_2CO_3’, ‘NaHCO_3’, ‘NaOH’).

The values of ‘k1,’ ‘k2’, ‘k3’ and ‘k4’ were determined through the utilization of these chemical reactions as scrutinized previously by (Patan, 2021). Following this, a time vs. concentration graph was generated utilizing MATLAB 2024 programming, as illustrated in Fig. 9. Within Fig. 9, the lines colored blue, red, and green portray the simulated concentration profiles of Na2CO3, NaHCO3, and NaOH, respectively. It is noteworthy that after 90 min, NaOH becomes entirely consumed in the chemical reaction, marking the equilibrium point, which is a result of the concurrent increase in the concentrations of Na2CO3 and NaHCO3.

Verification visual assessment employing MATLAB 2024 (www.mathworks.com) Programming for the carbonation process of process liquor in the mining and mineral processing sector.

Conclusions

Based on the determined rate constants (k₁, k₂, k₃, and k₄), the carbonation process can be effectively implemented in continuous, semi-batch, or batch reactor systems. Successful large-scale batch experiments have demonstrated the feasibility of this technology for adoption in the mining and mineral processing industries. This approach offers significant potential for controlling carbon emissions, mitigating global warming, reducing atmospheric temperature rise, and curbing industrial pollution. Furthermore, the experimental data supports the design and optimization of gas-liquid absorbers tailored for industrial use, and ongoing research is focused on enhancing these systems.

Analysis of Na₂CO₃, NaHCO₃, and NaOH concentrations before and after carbonation revealed that complete consumption of sodium hydroxide corresponds to 100% carbonation efficiency of the process liquor. This not only presents a viable method for emission reduction but also provides economic advantages by eliminating the need for purchased CO₂. These economic implications offer further opportunities for cost-benefit analyses and future research.

The use of boiler stack flue gas as a CO₂ source can also lead to a reduction in stack outlet temperatures, necessitating the selection of appropriate materials of construction (MOC) for stack design. However, direct flue gas purging introduces additional reactive components that may form secondary products, making selective CO₂ extraction a critical consideration. Alternatively, a more detailed characterization of the process liquor is essential if direct flue gas injection is pursued, which could offset the capital investment required for CO₂ extraction units. While similar carbonation strategies have been explored in other mineral processing contexts, the investigation involving pitchblende and uraninite ores is unique. This work provides a promising pathway toward developing carbon-neutral operations and represents a meaningful advancement in addressing the global climate crisis.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

Abbreviations

- SO3 :

-

Sulfur Trioxide

- NO2 :

-

Nitrogen Dioxide

- Conc.:

-

Concentrated

- CCUS:

-

Carbon Capture and Utilization

- Na2CO3 :

-

Sodium Carbonate

- NaOH:

-

Sodium Hydroxide

- Ba(OH)2 :

-

Barium Hydroxide

- g/L:

-

Gram Per Litre

- CO2 :

-

Carbon Dioxide

- N2 :

-

Nitrogen

- CCS:

-

Carbon Capture and Storage

- MT:

-

Metric Ton

- LDO:

-

Light Diesel Oil

- ppm:

-

Parts Per Million

- Max. :

-

Maximum

- mg of KOH/G:

-

Acid Concentration in a Nonaqueous Solution

- hr:

-

Hour

- Min. :

-

Minimum

- cSt:

-

Centistokes

- H2O:

-

Water

- COx:

-

Carbon Oxides

- NOx:

-

Nitrogen Oxides

- SOx:

-

Sulphur Oxides

- O2 :

-

Oxygen

- HC:

-

Hydrocarbon

- DG:

-

Diesel Generator

- CPCB:

-

Central Pollution Control Board

- APH:

-

Air Pre Heater

- NaHCO3 :

-

Sodium Bicarbonate

- O/L:

-

Outlet

- I/L:

-

Inlet

- FD:

-

Forced Draught

- PA:

-

Particulate Matter

- MOC:

-

Material of Construction

- $:

-

Dollar

- pH:

-

The potential of Hydrogen

- %:

-

Percentage

- °C:

-

Degree Celsius

- ml:

-

Millilitre

- Cs:

-

Concentration of Carbon Dioxide

- kg:

-

Kilogram

- m2 :

-

Square Meter

- t:

-

Time

- mg:

-

Milligram

- Nm3 :

-

Normal Cubic Meter

- kw:

-

Kilowatt

- V:

-

Volt

- Hz:

-

Hertz

- Kpa:

-

Kilopascal

- MW:

-

Megawatt

- L:

-

Liter

- mol/L:

-

Moles Per Liter

- min:

-

Minute

- g:

-

Gas

- l:

-

Liquid

- aq:

-

Aqueous

- s:

-

Solid

References

Abanades, J. C. et al. Capturing CO2 from combustion flue gases with a carbonation calcination loop. Experimental results and process development. Energy Procedia. 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2009.01.151 (2009).

Suri, A. K. Innovative process flowsheet for the recovery of Uranium from Tummalapalle Ore. BARC Newsletter, Issue No. 317. (2010), December.

Aravind, R. A., Muthukumar, V., Kumaravel, S. & Sivaprakash, E. Performance assessment of 2×90 tph (afbc) boiler and study of hp heater. Mater. Today: Proc. 37, 404–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.05.389 (2021).

Baena-Moreno, F. M., Leventaki, E., Riddell, A., Wojtasz-Mucha, J. & Bernin, D. Effluents and residues from industrial sites for carbon dioxide capture: a review. In Environmental Chemistry Letters 21(1). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-022-01513-x

Bandla, Y. & Thamida, S. K. Flow-Accelerated corrosion characterization of magnesium in NaCl solution and a case study by computational fluid dynamics simulation. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 19(5). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11668-019-00743-6 (2019).

Chaturvedi, K. R., Sinha, A. S. K., Nair, V. C. & Sharma, T. Enhanced carbon dioxide sequestration by direct injection of flue gas doped with hydrogen into hydrate reservoir: Possibility of natural gas production. Energy 227, 120521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.120521 (2021).

Fu, D. & Davis, M. E. Carbon dioxide capture with zeotype materials. In Chemical Society Reviews (Vol. 51, Issue 22). (2022). https://doi.org/10.1039/d2cs00508e

Gao, W. et al. Industrial carbon dioxide capture and utilization: State of the art and future challenges. In Chemical Society Reviews (Vol. 49, Issue 23). (2020). https://doi.org/10.1039/d0cs00025f

Godin, J., Liu, W., Ren, S. & Xu, C. C. Advances in recovery and utilization of carbon dioxide: A brief review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. (Vol 9(Issue 4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2021.105644 (2021).

İsmail Tosun, Y. Microwave Carbonation of Thermal Power Plant Flue Gas/CO 2 by Fly Ash/Coal Char for Soil Remediation and Ground Stabilization. In Carbon-Based Material for Environmental Protection and Remediation. IntechOpen. (2020). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.91342

Izidoro, J. D. C., Fungaro, D. A., Viviani, L. C. & Silva, R. D. C. Brine sludge waste from a Chlor-alkali industry: characterization and its application for non-structural and structural construction materials. J. Appl. Mater. Technol. 3(1). https://doi.org/10.31258/jamt.3.1.1-7 (2021).

Jazmin Murphy. Calculate Emissions by Country: View Carbon Footprint Data Around the World. Carbon Ecological Footprint Calculators. (2023), July 10.

Lin, X. et al. Carbon dioxide sequestration by industrial wastes through mineral carbonation: current status and perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 434 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.140258 (2024).

Muradov, N. Industrial Utilization of CO2: A Win–Win Solution (pp. 325–383). (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-0545-4_9

Patan, A. K. & Thamida, S. K. Modeling and simulation of distillation of a binary non-reacting mixture using rate-based approach in packed column under total reflux. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 40(2). https://doi.org/10.30492/ijcce.2020.110282.3640 (2021).

Proaño, L., Sarmiento, A. T., Figueredo, M. & Cobo, M. Techno-economic evaluation of indirect carbonation for CO2 emissions capture in cement industry: A system dynamics approach. J. Clean. Prod. 263 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121457 (2020).

Quadrelli, E. A., Centi, G., Duplan, J. L. & Perathoner, S. Carbon dioxide recycling: Emerging large-scale technologies with industrial potential. In ChemSusChem (Vol. 4, Issue 9). (2011). https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201100473

Rahmanihanzaki, M. & Hemmati, A. A review of mineral carbonation by alkaline solidwaste. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 121 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2022.103798 (2022).

Rajesh, L. S. K. V. (2019). Case study of air quality at tummalapalle mill and effective actions for improvement. In Nuclear Fuel Complex (NFC) (Ed.), DAE Safety & Occupational Health Professional Meet, (DAE SOHPM) (2–6). Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB), Mumbai.

Rajesh, N. V. R. T. R. M. S. Effectiveness of autoclave agitator in alkali leaching based ore processing plant. In KIIT & IIM (Eds.), 77th ATM IIM. Indian Institute of Metals. (2023).

Rao, M. S. (2019a). Management of alkali leaching based uranium tailings at tummalapalle. In IAEA website (Ed.), UPC (1–8). UMREG Presentations.

Rao, M. S. S. S., R. L. K. Effective use of LDO fired boiler flue gas in carbonation of process liquor at alkali leaching based Tummalapalle Mill. CEM India International Conference, Asian Environmental Technology Journal, 23(4), 37–39. (2019).

Rasul, M. G., Moazzem, S. & Khan, M. M. K. Performance assessment of carbonation process integrated with coal fired power plant to reduce CO2 (carbon dioxide) emissions. Energy 64 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2013.09.047 (2014).

Reddy, B. N. K., Thamida, S. K. & Sharma, V. K. Evaluation of evaporation characteristics concerning environmental parameters for recycled water facility in mineral processing industry. In ISDE (Ed.), 9th Digital Earth Summit-2022 (75). Institute of Remote Sensing, Anna University. (2022).

Reddy, B. N. K., Sunil, T. & Sharma, V. K. Case Study on Advanced Separation Techniques used in Alkali Leaching based Mineral Processing Plant. ICSPT 2023, IIT Patna, AIJR Publisher, DOI: 10.21567/Abstracts.165. (2024).

Reddy, T. C. S., Reddy, N. V. & Rao, L. K. Technical modifications of alkali leaching circuit to improve slurry throughput into the autoclave. In 74th Annual Session of Indian Institute of Chemical Engineers (IIChE) & I. of M. & M. T. CSIR (Eds.), CHEMCON, ID: DMFDPD-183, CSCE (p. 877). Indian Chemical Engineering Congress. (2021).

Rusanowska, P., Zieliński, M. & Dębowski, M. Removal of CO2 from biogas during mineral carbonation with waste materials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 20(Issue 9). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095687 (2023).

Satpati, S. K. et al. Trial of pilot scale nanofiltration unit for improvement of precipitation circuit at tummalapalle mill. CNSE Journals 2(1), 528–543 (2025).

Saravanan, A. et al. S., A comprehensive review on different approaches for CO2 utilization and conversion pathways. Chemical Engineering Science 236. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2021.116515

Sarkar Suman, K. J. D. A view on advanced separation techniques used in various uranium processing plant of Uranium Corporation of India Limited (UCIL). In DAE-BRNS (Ed.), SESTEC – 2022 (pp. 33–33). Institute of Chemical Technology (ICT). (2022).

Schmid, C. & Hahn, A. Potential CO2utilisation in Germany: An analysis of theoretical CO2demand by 2030. Journal of CO2 Utilization 50 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2021.101580

Sharma, V. K. et al. Technical modification of alkali leaching circuit to improve slurry throughput into the autoclave. Suranaree J. Sci. Technol. 30(4). https://doi.org/10.55766/sujst-2023-04-e0998 (2023).

Sharma, V. K., Thamida, S. K. & Reddy, B. N. K. Engineering study of water jacket system in place of a spiral heat exchanger at mining and mineral ore processing industry. Eur. Chem. Bull. 12(7), 1507–1512 (2023).

Sharma, V. K., Thamida, S. K. & Reddy, B. N. K. Carbonation and modeling study for process liquor in batch mode using flue gas in the mining and mineral processing industry. Chem. Pap. 78(7). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11696-024-03379-5 (2024).

Sharma, V. K., Thamida, S. K. & Reddy, B. N. K. Scaled-Up Carbonation of Pitchblende and Uraninite Process Liquor Using Flue Gas: Kinetic Modelling and Comparative Analysis. (2025). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5197260

Sharma, V. K. & T. S. K., R. B. N. K Study of waste management treatment facilities using advanced membrane bio reactor (MBR) technology. Pollution Study Asia Pac. Acad. Sci. Pte Ltd. 6(2), 1–18 (2025).

Siddique, S., Srinivas, K., Mandre, N. R., Venugopal, R. & Srivastava, S. K. Improvements in autoclave heat recovery circuit in uranium ore processing mill at tummalapalle, India. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 68(4). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12666-014-0494-4 (2015).

Singh, A. K., Suri, A. K. & Jha, G. A. B. H. R. C. C. K. Studies on precipitation and separation of sodium di-uranate from leach liquor of tummalapalle uranium ore. (2014).

Song, C. Global challenges and strategies for control, conversion and utilization of CO2 for sustainable development involving energy, catalysis, adsorption and chemical processing. Catal. Today 115, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2006.02.029 (2006).

Sreenivas, T. R. K., A. R., M. M. Autoclave Leaching of Refractory Uranium Minerals. BARC Newsletter, International Seminar on Mineral Processing Technology. (2010), December.

Sriharsha, P., Rao, L. K. & Sarkar, S. Process intensification in post alkali leached liquor precipitation circuit using re-dissolution of sodium diuranate slurry. In KIIT & IIM (Eds.), 77th ATM IIM. (2023).

Teir, S., Kotiranta, T., Pakarinen, J. & Mattila, H. P. Case study for production of calcium carbonate from carbon dioxide in flue gases and steelmaking slag. J. CO2 Utilization 14 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2016.02.004 (2016).

Thamida, S. K., Reddy, B. N. K. & Sharma, V. K. Detailed calculations for rainwater recharge system, considering the storm water runoff and geological formation. In JNAFAU Hyderabad (Ed.), PEEC-2023, ISBN No: 978-93-95855-02-3 (Vol. 6, pp. 40–46). Pure Earth Foundation & 3520/2, Chotani Manjil, Nicholson Road Mori Gate, Delhi – 110006. (2023).

Theo, W. L., Lim, J. S., Hashim, H., Mustaffa, A. A. & Ho, W. S. Review of pre-combustion capture and ionic liquid in carbon capture and storage. In Applied Energy (Vol. 183). (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.09.103

UCIL. Light Diesel Oil, 600 KL, TMPL/PUR/037/275/126, Purchase Tender. (2017).

Varvoutis, G., Lampropoulos, A., Mandela, E., Konsolakis, M. & Marnellos, G. E. Recent Advances on CO2 Mitigation Technologies: On the Role of Hydrogenation Route via Green H2. In Energies (Vol. 15, Issue 13). (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/en15134790

Wawrzyńczak, D. Industrial carbon dioxide capture and utilization technology. In The Carbon Chain in Carbon Dioxide Industrial Utilization Technologies (1–15). CRC. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003336587-1 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to the management of Uranium Corporation of India Limited for granting them the opportunity to gain practical experience in the mining and mineral processing sector. They also express their appreciation to the administrative team of the Department of Chemical Engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology, Tirupati, for their support and encouragement in pursuing this research endeavor.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Vipin Kumar Sharma, Sunil Kumar Thamida, Bhumireddy Naveen Kumar Reddy; data collection: Vipin Kumar Sharma; analysis and interpretation of results: Sunil Kumar Thamida, Bhumireddy Naveen Kumar Reddy; draft manuscript preparation: Vipin Kumar Sharma, Sunil Kumar Thamida. Editing and conception: Vipin Kumar Sharma, Sunil Kumar Thamida, Bhumireddy Naveen Kumar Reddy; review and execution: Sunil Kumar Thamida, Bhumireddy Naveen Kumar Reddy; guidance and approval: Sunil Kumar Thamida, Bhumireddy Naveen Kumar Reddy. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

Consent for publication was obtained from all individuals for this technical paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, V.K., Thamida, S.K. & Reddy, B.N.K. Process liquor carbonation and simulation on an industrial scale, harnessing exhaust gas from light diesel oil fired boilers in mining and ore processing plants. Sci Rep 15, 33778 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00060-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00060-z